Soixante-seize dessins (1ere série) tracés par l’Oknha Tep Nimit Mak et l’Oknha Réachna Prasor Mao, Architecte et Architecte-adjoint du Palais Royal de Phnom Penh, réunis et présentés par George Groslier. [76 Drawings (1st inst.) drawn by Oknha Tep Nimith Mak and Oknha Reachan Prasor Mao, Head Architect and Deputy Architect of Phnom Penh Royal Palace, gathered and introduced by George Groslier.]

T1, vol.4 of Arts & Archéologie Khmers review, launched by George Groslier in 1921, one year after the opening of Musée Albert-Sarraut (now National Museum of Cambodia សារមន្ទីរជាតិ) in Phnom Penh on 13 April 1920, and published until 1924.

The drawings

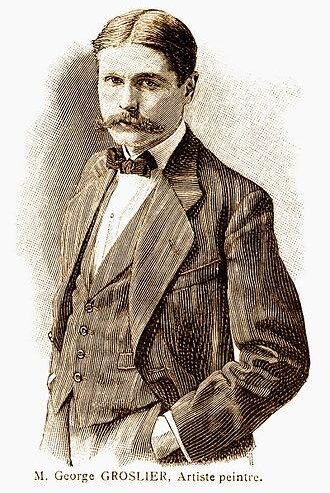

In his introduction, Groslier — himself a noted visual artist who had created the first tourism poster for Angkor in 1917, remapped the historic context of these drawings:

On né saurait rigoureusement ce qu’était un dessin indigène avant 1863, date du début de notre Protectorat, en étudiant à la lettre ceux que nous présentons aujourd’hui. Les originaux du siècle dernier sont quasiment introuvables en raison de leur fragilité et des conditions de la vie et de l’habitation cambodgiennes. Le papier d’une part, de l’autre la mince couche de peinture à la colle dont furent parées quelques pagodes, né pouvaient résister à l’humidité, aux termites, à la fumée des foyers, des torches ou de lampe à l’huile du Cambodge du XIXe siècle. Le musée Sarraut né possède qu’une dizaine de peintures en mauvais état qui né remontent qu’à 1906, et qui dans quelques années d’ailleurs n’y seront plus. Les dessins de ce fascicule, tracés à la plume sur papier écolier, né peuvent donc donner l’aspect de ceux d’autrefois — il en retiennent au moins les canons, la signification et l’armature.

Ce sera au lecteur de faire la part des choses, d’annuler une froideur parfois un peu sèche et une impeccable netteté pour retrouver la verve ancienne qui se révèle pourtant à qui veut voir. Perdant dans le sens que nous venons d’indiquer, nos dessins s’averent beaucoup plus variés qu’ils né le furent jadis. Si leur auteurs les ont exécutés dans la plus absolue liberté et sans que jamais le moindre détail, la plus petite ligne n’ait jamais été retouchés ni même inspirés par nous — nous demandâmes quelques thèmes nouveaux, des applications de décor à une surface quelconque. Il s’agissait en fait de reconnaître si notre Khmer contemporain n’était pas un plat copiste, un rabâcheur et s’il n’était que cela. L’artiste suivit donc ces thèmes nouveaux. Il amalgama à de vieux canons parfaitement conservés des trouvailles personnelles. Aussi son oeuvre comporte une part d’impersonnalité traditionnelle et une part d’intelligence nettement consciente, vivante. Dans l’impuissance où nous demeurons d’établir le bilan complet de l’art graphique khmer d’il y a 60 ans, nous possédons néanmoins des spécimen où tout ce qui en survit demeure enclos el féconde les expressions actuelles, avant qu’il né soit trop tard — spécimens que notre publication du moins fixe pour l’avenir. […]

Pour un oeil cambodgien il n’y a pas de dessin simple et facile, complexe et difficile, car dans le tracé le plus simple toutes les difficultés pratiques et artistiques sont réunies: la connaissance des canons, la perfection de l’éxécution. Ainsi, ce qui nous apparaît compliqué dans le dessin de la fig. 99 par exemple né devient plus pour le Cambodgien qu’une question de temps et de patience — c’est-à-dire des facteurs sans aucune valeur pour lui . En y regardant de bien près, aucun problème technique nouveau né surgit. Le canon règle aussi bien le tracé d’un Naga à trois tetes simples que celui à onze têtes flamboyantes et celui-ci est à celui-là ce qu’un groupe de onze multiplications successives est à un groupe de trois.

[We would not know exactly what indigenous drawing was before 1863, the date of the beginning of our Protectorate, by studying to the letter those that we present here. The originals from the last century are almost impossible to find due to their fragility, and to the realities of Cambodian daily life and habitat. The paper

on the one hand, on the other the thin layer of glue paint with which some pagodas were adorned, could not resist humidity, termites, smoke from fireplaces, torches or oil lamps from the 19th century Cambodia. The Sarraut Museum only has around ten paintings in poor condition which date back to 1906 only, and which in a few years will no longer be there. The drawings in this booklet, drawn in pen on school paper, cannot therefore give the appearance of those of the past — they at least retain the canons, the meaning and the framework.

It will be up to the reader to sort things out, to go past a sometimes somewhat dry coldness and an impeccable clarity, in order to rediscover the old verve which nevertheless reveals itself to those who are eager to see. While losing in the sense that we have just indicated, our drawings turn out to be much more varied than they once were. If their authors executed them in the most absolute freedom and without ever the slightest detail, the smallest line having ever been retouched or even inspired by us — we asked for some new themes, applications of décor to any surface. It was in fact a matter of reckoning if our contemporary Khmer artist were not merely a copyist endlessly rehashing, and only just that. And, in fact, this artist tackled these new themes. He combined perfectly preserved old cannons with personal finds. Thus, his work included a part of traditional impersonality and a part of clearly conscious, living intelligence. In the powerlessness in which we remain to establish the complete assessment of Khmer graphic art from 60 years ago, we nevertheless possess specimens where everything that survives remains enclosed and fertilizes current expressions, before it is too late — specimens that our publication at least sets for the future. […]

To the Cambodian eye, there is no simple and easy drawing, nor complex and difficult, because in the simplest drawing all the practical and artistic difficulties are united: the knowledge of the classic models, the perfection of the execution. Thus, what appears complicated to us in the drawing of fig. 99 for example becomes for the Cambodian only a question of time and patience — that is to say factors of no value to him. Looking closely, no new technical problems arise. The canonical model regulates the outline of a Naga with three simple heads as well as that of eleven flaming heads and the latter is to the former what a group of eleven successive multiplications is to a group of three.]

The authors

Earlier, Groslier had recounted the career of the two artists, Oknha Tep Nimith Mak and Oknha Reachna Prasor Mao [1], who in addition to their activities as royal architects were also involved in art teaching. Tep Nimith Mak, in particular, had his own school of art students who took part in major artistic creations such as the Reamker frescoes at the Silver Pagoda, noting that “tous ces dessins ont été exécutés dans un but pedagogique” [“all these drawings were made for educational purposes”]:

Le premier des deux auteurs est l’Oknha Tep Nimit Mak, né en 1856 a Phnom Penh, architecte du Palais Royal depuis 1897, élevé à toutes les dignités indigènes, chevalier do la Legion d’honneur et directeur cambodgien de l’École des arts de Phnom Penh depuis sa fondation en 1918. Les oeuvres de ce Cambodgien éminent sont nombreuses dans le pays. Il construisit notamment les grandes pagodes royales de Chruy Ta Keo (Lok Dek), du Phnom Del (Cheung Prei), du Phnom Kruong (Lovek), de Samret Thichei (Anluong Réach). Il apprit son art durant un stage religieux de six années à la pagode de Botum Vodei a Phnom Penh, d’un bonze dessinateur-architecte nommé Yaos (entre 1868 – 1874), et que n’avait par conséquent pas encore tonché l’influence française alors à son début. Dans sa jeunesse, l’Oknha Mak fut également sculpteur. En 1903 – 4, il traça les épisodes des Ramayana que l’on voit autour de la Pagode d’argent de Phnom Penh. Son père était mandarin et son grand-pere sculpteur. Si son grand åge et le tremblement de sa main lui interdisent désormais tout travail effectif, il n’en demeure pas moins l’homme le plus compétent en matière d’art cambodgien qui se puisse actuellement trouver au Cambodge.

L’Oknha Réachna Prasor Mao est né en 1871 à Vihear Tuontin, province de Kandal. Architecte adjoint du Palais depuis 1914, officier d’Académie, fils d’un cultivateur et petit file d’un architecte-charpentier, il est de formation provinciale. C’est un températment actif et en beaucoup de points très différent du précédent. Son éducation artistique remonte également à son stage religieux qui dura 13 ans (1877−1840). Apres avoir quitté la bonzerie, il travailla avec cinq maîtres différents, architectes, sculpteurs et dessinateurs. Il est exécutant des dessins ci-après, arrêtés et concertés de compagnie avec l’Oknha Mak. L’association de ces deux personnalités offre done à nos recherches toute la sécurité désirable et ce que l’art contemporain peut émaner de plus pur et de plus traditionnel.

Des “couleurs a l’eau” de pacotille, des cahiers d’écolier, des plumes, des crayons arriverent par tonnes au Cambodge postérieurement à la formation de nos deux sujets, se substituant aux procédés indigènes et dénaturant par conséquent l’aspect original des anciens dessins. Que de tels accessoires aient facilité certaines oeuvres graphiques, qu’ils les aient abimées ou ameliorées, la question né se pose pas ici. Nos dessins né valent pas en tant qu’oeuvre d’art, mais à titre de document. Ce qu’il y a de certain et d’intéressant, est que lorsque les Oknha Mak et Mao étaient apprentis à la bonzerie, ils apprirent à dessiner sur des ardoises indigènes et ces grandes feuilles de papier khmer pliées ensuite en accordéon et que j’ai décrites ailleurs.

[The first of the two authors is Oknha Tep Nimit Mak, born in 1856 in Phnom Penh, architect of the Royal Palace since 1897, elevated to all the native dignities, knight of the Legion of Honor and Cambodian director of the School of Arts of Phnom Penh since its foundation in 1918. The works of this eminent Cambodian are numerous in the country. He notably built the large royal pagodas of Chruy Ta Keo (Lok Dek), Phnom Del (Cheung Prei), Phnom Kruong (Lovek), and Samret Thichei (Anluong Réach). He learned his art during a six-year religious internship at the Botum Vodei pagoda in Phnom Penh, from a monk designer-architect named Yaos (between 1868 – 1874), and who had therefore not yet been influenced by French then at its beginning. In his youth, Oknha Mak was also a sculptor. In 1903 – 4, he traced the episodes of the Ramayana which can be seen around the Silver Pagoda in Phnom Penh. His father was a mandarin and his grandfather was a sculptor. If his great age and the trembling of his hand now prevent him from any effective work, he nonetheless remains the most competent man in Cambodian art who can currently be found in Cambodia.

Oknha Réachna Prasor Mao was born in 1871 in Vihear Tuontin, Kandal province. Deputy architect of the Palace since 1914, Academy officer, son of a farmer and granddaughter of an architect-carpenter, he had provincial training. It is an active temperament and in many points very different from the previous one. His artistic education also dates back to his religious internship which lasted 13 years (1877−1840). After leaving the bonzerie, he worked with five different masters, architects, sculptors and designers. He is executing the following designs, agreed and agreed in company with Oknha Mak. The association of these two personalities therefore offers our research all the desired security, and the purest and most traditional expression that contemporary art can achieve.

Junk “water colors”, school notebooks, feathers, pencils reached Cambodia by the tons, way after the training of our two subjects, replacing indigenous processes and consequently distorting the original appearance of the old drawings. Whether such accessories facilitated certain graphic works, whether they damaged or improved them, the question will not be dealt with here. Our drawings are not valid as a work of art, but as a document. What is clearly, and interesting, is that when Oknha Mak and Mao were apprentices at the monastery, they learned to draw on native slates and these large sheets of Khmer paper then folded like an accordion, the latter I have described elsewhere.]

Defence and illustration of Khmer art

Artist, educator, convinced that French Protectorate only could save the artistic traditions of Cambodia, Groslier elaborated on educational and handover challengers: ’

La progression des difficultés ou de la complexité de tracés n’est pas la même pour un Khmer que pour nous. Évaluer cette pédagogie au contact de la nôtre serait doublement ridicule, par cela meme d’abord, ensuite en raison de l’inanité de la plupart des programmes scolaires artistiques en usage dans nos écoles d’Occident. Sachons en effet que ces dessins sont destinés à des enfants de 10 à 16 ans et que ce fut d’après ces même modèles que les Oknha Mak et Mao apprirent naguère leur métier. […] Le personnage choisi dicte ses proportions, impose ses attitudes, règle son vetement, ordonne ses couleurs symboliques. Chaque fois donc que dans l’avenir l’artiste songera à ce personnage, un déclenchement automatique se produira dans sa mémoire comme autant de roues qui se mettraient à tourner en entraînant par un engrenage étroitement réglé. Si nous reprenons en exemple la figure de Sugriva, Hanuman, etc., et les masques de danse déjà comparés dans leurs forme, nous verrons qu’ici et là Hanuman sera blanc avec des spirales rouges simulant les touffes de poil, et Sugriva rouge brique. Mêmes couleurs sur nos peintures de 1906. Il en était certainement ainsi il y a huit siècles. Évidemment, si cet artiste, apres cela, né voulait pa une exécution parfaite, il né serait pas raisonnable. Mais vouloir seulement cela dejá n’est pas une mince ambition et y parvenir au point ou il nous est donné de le vérifier n’est certes pas un piètre résultat. Nos artistes contemporains occidentaux soi-disant si cérébraux et

personnels s’expriment dans une exécution souvent si lamentable- et il y a tant de cérébraux! — qu’on se demande en fin de compte s’il n’est pas plus difficile d’être manuel, tout bonnement.

Cette réflexion qui vient a quiconque fréquente un peu les maîtres du passé et se souvient des artisans de l’époque de Cellini ou de nos émailleurs limousin, réflexion que nous suggere l’artiste khmer au travail, terminera notre étude. Mais pour prévenir l’abus qu’on peut en faire nous devons mettre en lumière la cérébralité de l’artiste khmer. Comparez l’écolier européen qui copie une chaise, un pot à eau, un arrosoir, et l’écolier khmer qu’à aucun moment on né trouvera devant de pareils modèles, mais qui au contraire, dès qu’il prend un crayon , trace la silhouette d’un dieu auquel il croit, d’une de ces nymphes populaires, gracieuse et ravissante, dont tous le rêves de la race sont remplis. Concluez. Le “manuel” n’est peut-etre pas où l’on croit, et le “cérébral” né l’est peut-être pas autant qu’il semble à première vue. En comparant ensuite les satisfactions du “cérébral” qui réussit une brouette a celle du “manuel” qui voit devant lui et par ses soins surgir le dieu vénéré, protecteur du pays, les mots paraissent changer de signification.

[The progression of difficulty or complexity of drawings is not the same for a Khmer as for us. Evaluating this pedagogy in comparison with ours would be doubly ridiculous, firstly for that very reason, then because of the inanity of most of the artistic school programs in use in our Western schools. Let us recall that these drawings are actually intended for children aged 10 to 16, and that it was from these same models that Oknha Mak and Mao once learned their trade. […] The select character dictates its proportions, imposes its attitudes, regulates its clothing, orders its symbolic colors. Each time in the future the artist thinks of this character, an automatic trigger will occur in his memory like so many wheels which would begin to turn, driven by a tightly regulated gear. If we take as an example the figure of Sugriva, Hanuman, etc., and the dance masks already compared in their form, we will see that here and there Hanuman will be white with red spirals simulating tufts of hair, and Sugriva brick red: same colors on our paintings from 1906. It was certainly this way eight centuries ago. Obviously, if this artist, after that, did not want a perfect execution, he would not be reasonable. But wanting just that already is no small ambition and achieving it to the point where we can verify it is certainly not a poor result. Our contemporary Western artists are supposedly so cerebral, and personal expressions are expressed in an execution that is often so pathetic — and there are so many cerebral ones! — that we wonder in the end if it is not more difficult to be manual, quite simply.

This reflection, which will come to anyone spending some time with the masters of the past and remembering the craftsmen of the time of Cellini or our Limousin enamellers — a reflection which the Khmer artist at work suggests to us -, will conclude our study. But to prevent the abuse that can be made of it, we must highlight the cerebrality of the Khmer artist. Compare the European schoolboy who copies a chair, a water pot, a watering can, and the Khmer schoolboy who at no time will we find in front of such models, but who on the contrary, as soon as he picks up a pencil, traces the silhouette of a god in whom he believes, of one of those popular nymphs, graceful and ravishing, with which all the dreams of the race are filled. In closing: the “manual” is perhaps not where you think it is, and the “cerebral” is perhaps not as much as it seems at first glance. By then comparing the satisfactions of the “cerebral” who succeeds in a wheelbarrow to that of the “manual” who sees emerging before him, and through his care, the venerated god, protector of the country, the words seem to swap their meaning.]

[1] In Recherches sur les Cambodgiens, Groslier was to pay tribute to the two architects, noting:

Je dois ici une mention toute spéciale à mes deux vieux et fidèles collaborateurs indigènes avec lesquels j’ai minutieusement travaillé depuis 1912 : l’Oknha Tep Nimit Mak, architecte du palais royal et l’Oknha Réachna Prasoer Mao, architecte aussi et tous les deux attachés à la Direction des arts cambodgiens. [p. 399].

Plate captions

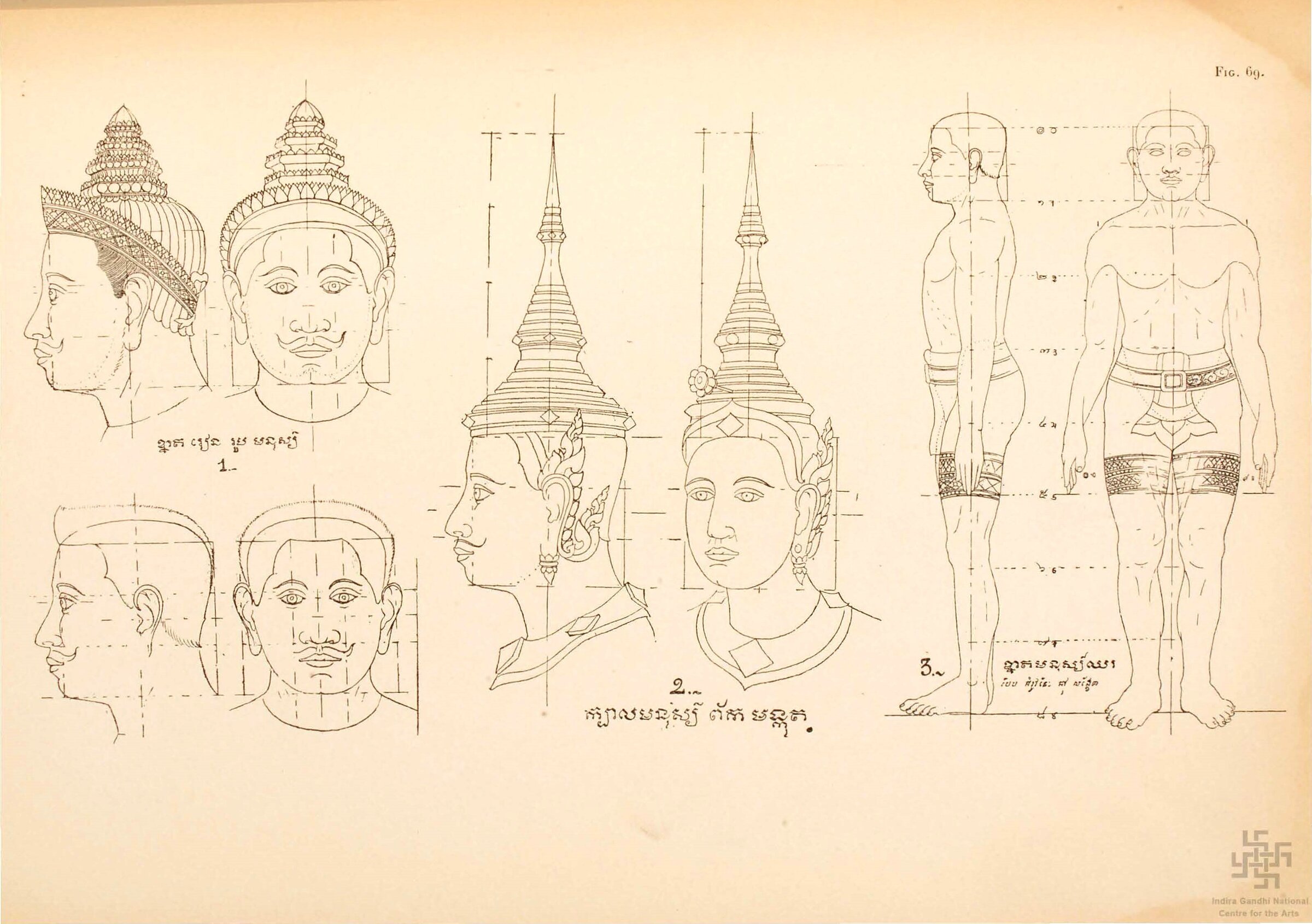

Plate 69 — Num 1: Modèle de visage d ‘homme. — La figure du haut est inspirée d’une tete de stalue classique. La partie conique de la coiffure (makuta) a été naïvement traitée en perspective. La tete du bas nous fait remarquer qu’en art contemporain comme en art classique les visages d’etres supérieurs sont souvent pourvus de moustaches. | Num 2: Tete d’homme portant le mokoth. Cette coiffure dérive de la précédente. Elle est inséparable de la représentation de tout héros ou héroïne, dieu ou déesse. A ces formes contemporaines se trouve mêlé le pendant d’oreille classique par excellence: stylisation du bouton do lotus. | Num 3: Tel est le canon du corps humain, huit faces dans le corps. On se demande pourquoi l’artiste a éprouvé le besoin de revêtir son exemple d’un caleçon classique. Cette proportion né semble pas correspondre à celle d’autrefois.

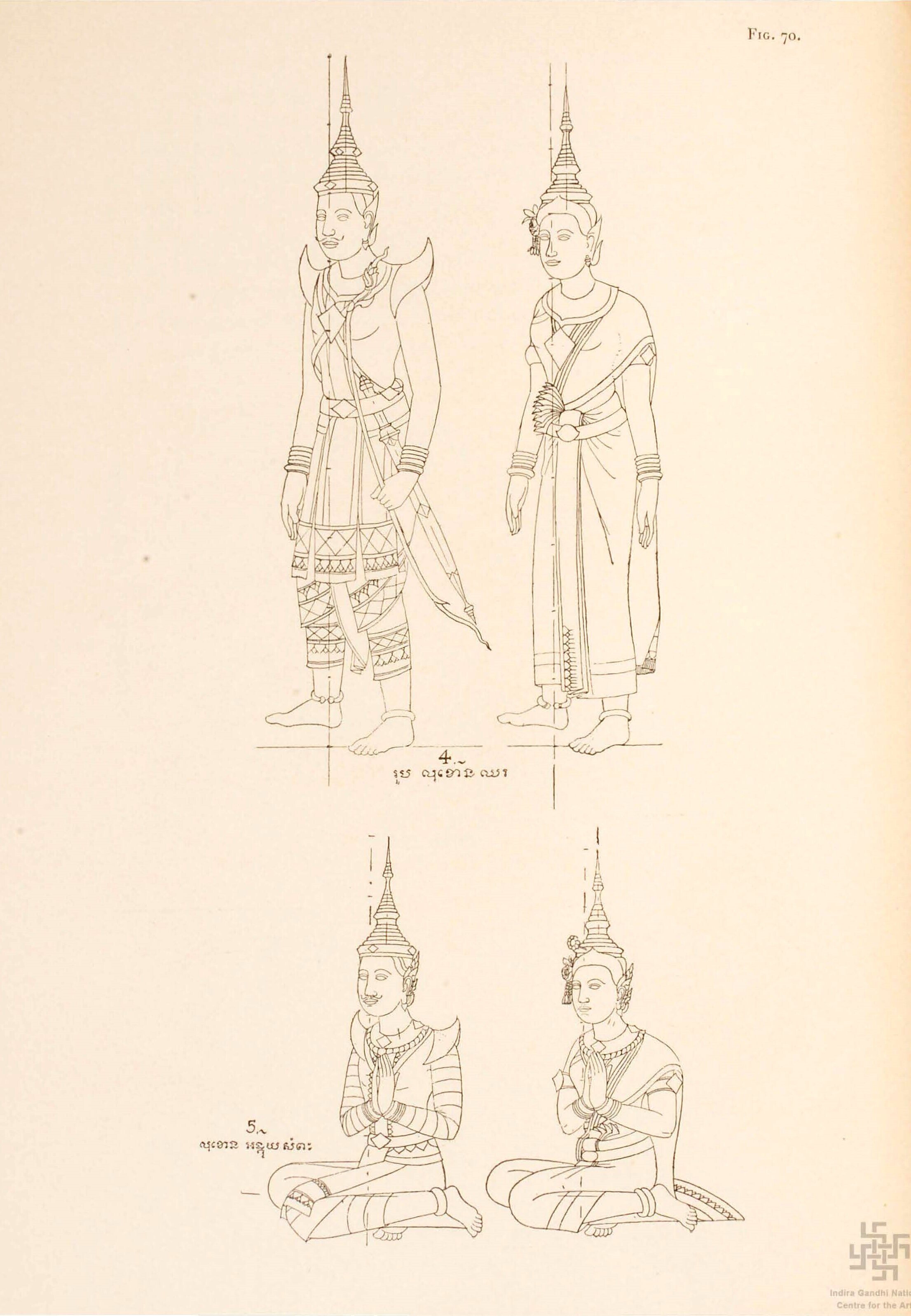

Plate 70 — Nos. 4,5: Représentation de lokhon debout et assise dans la position du sampéah (lokhon =

actrice, danseuse). Nous voyons là les détails du costume d’un prince ou dieu et d’ une princesse ou déesse. La sampéah est le grand salut, l’anjali de l’Inde.

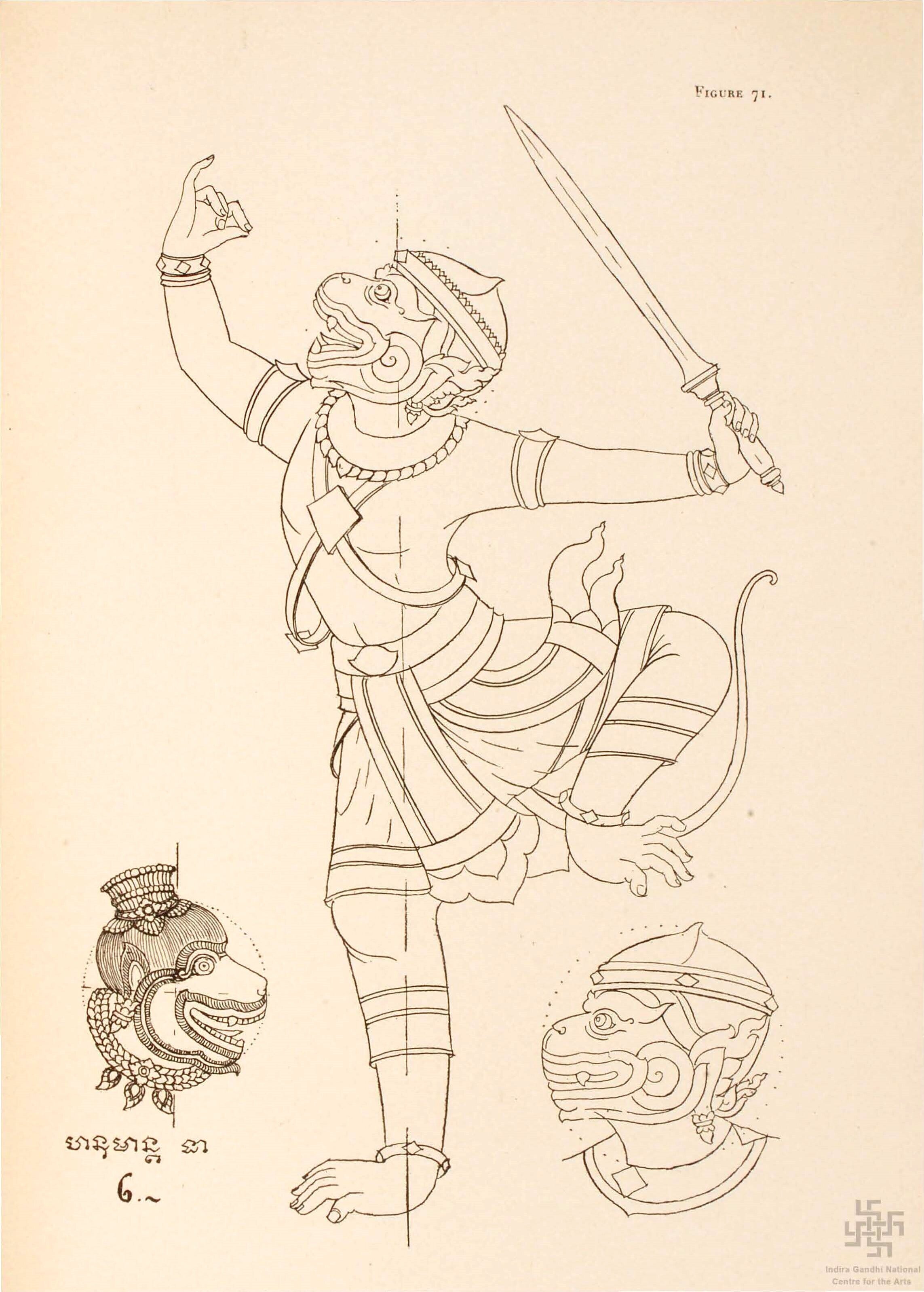

Plate 71 — No. 6. Hanuman. Le singe héroïque et guerrier, allié de Rama qu’il aide à retrouver Sita. C’est bien l’un des personnages les plus populaires du Ramayana khmer.

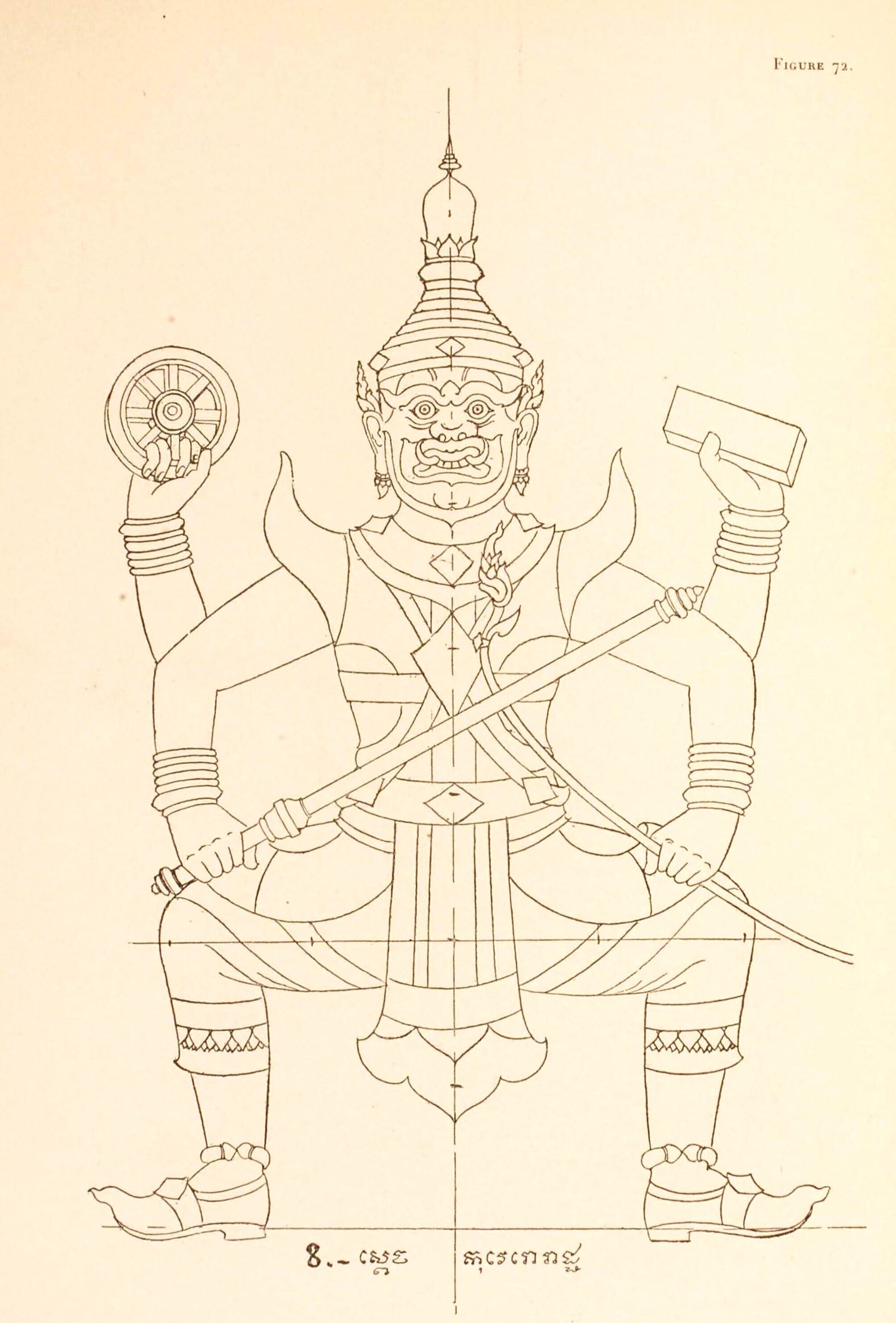

Plate 72 — No. 8. Samdach Kuveru Réach: Kubera. Pose de colère et de défi. Nous faisons connaissance avec Ie masque démoniaque.

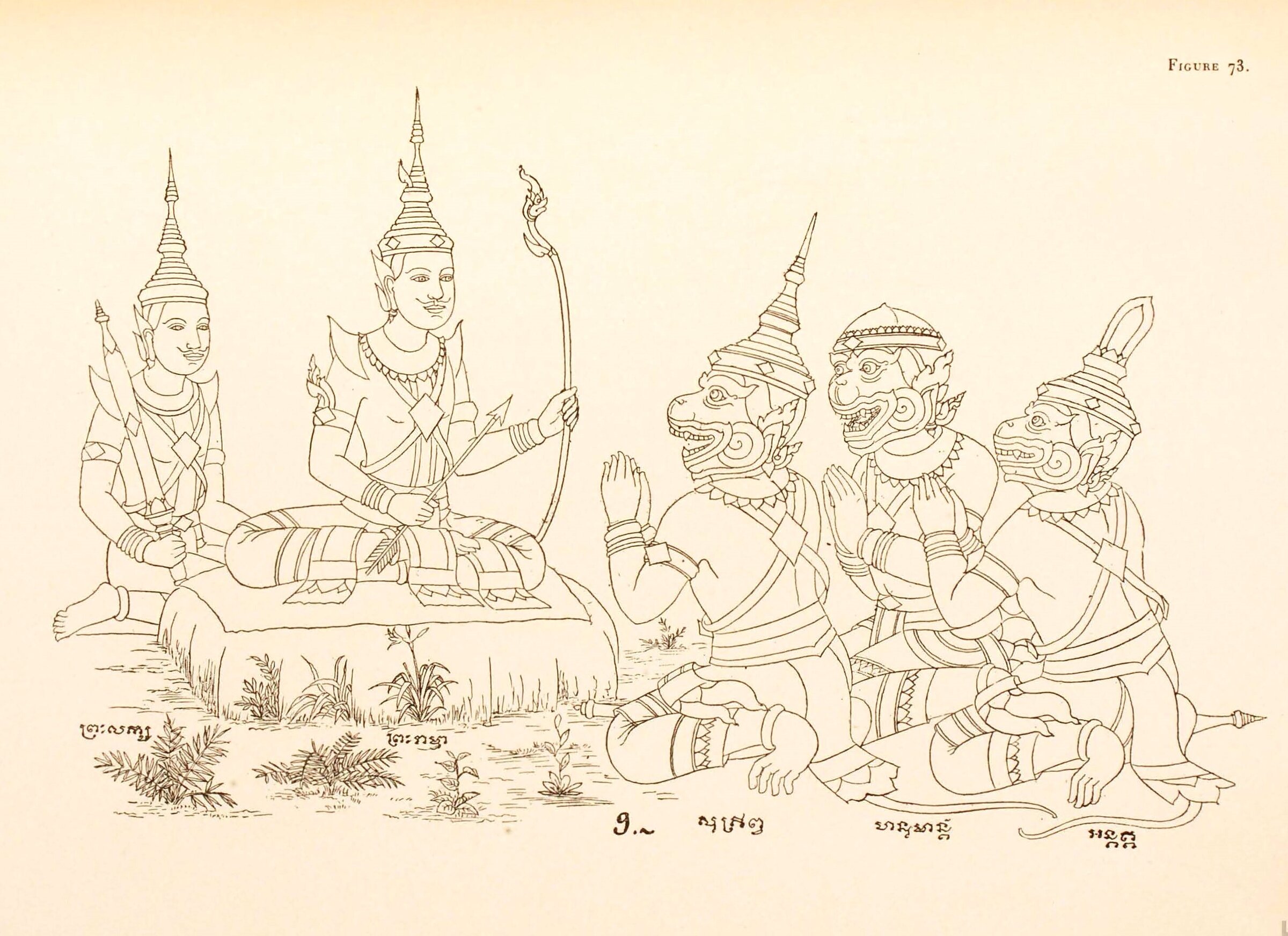

Plate 73 — No. 9. Après avoir étudié tous les détails suflisants, l’élève est ici convié à exécuter une scene complete de l’épopé. Nos trois héros do la fig. 114 demandent l’assistance de Prah Ream (Rama) et de son frere Prah Lakkhs (Lakshmana). Remarquer la minutie naïve des petites plantes à laquelle les vieux sculpteurs nous ont accoutumés dans leurs bas-reliefs.

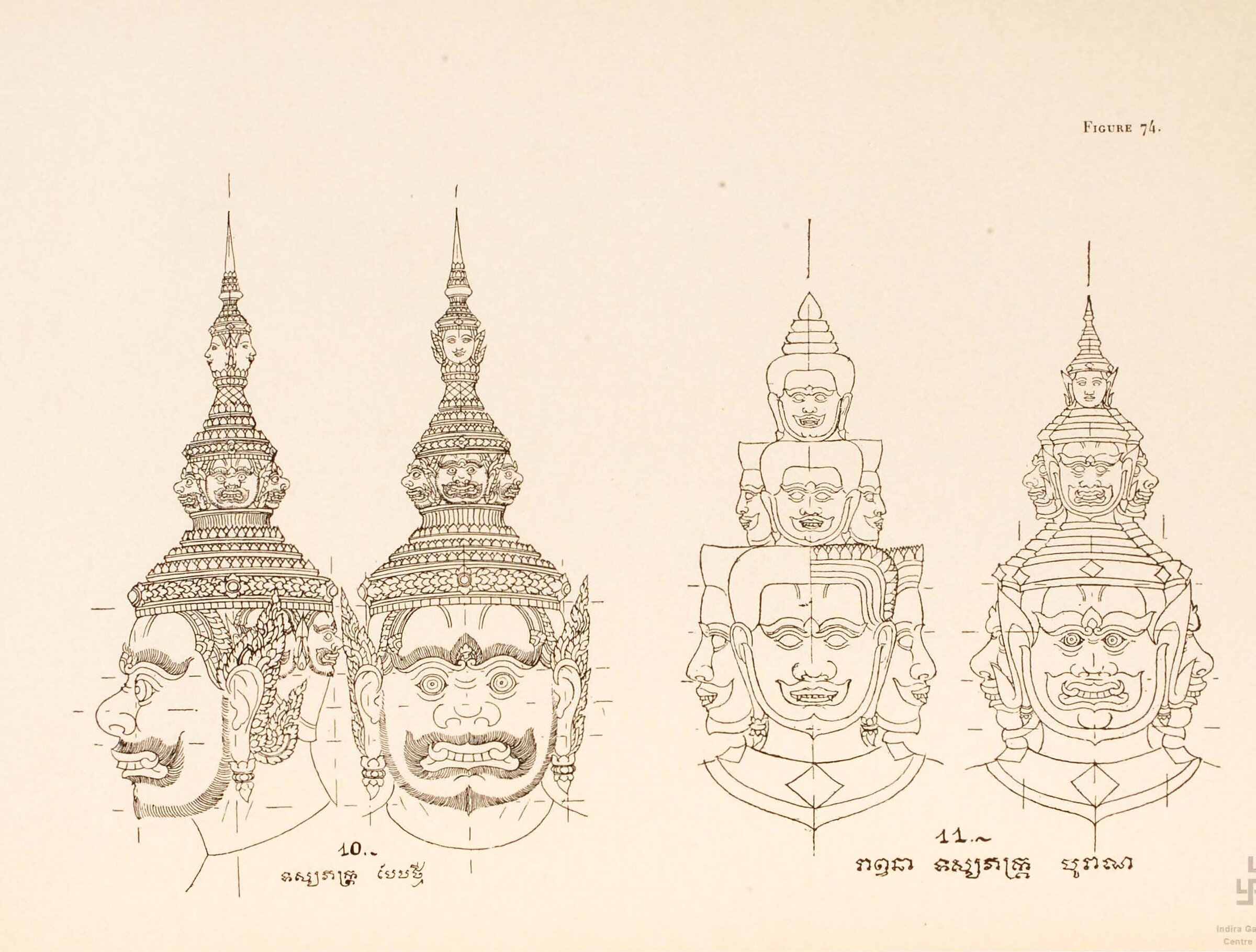

Plate 74 — No. 10. Tosaphakr (modele nouveau). Ravana, le ravisseur de Sita, roi des Yakshas et de Lanka, le “monstre aux dix tetes”. | Le No. 11 nous permet une comparaison avec le Ravana classique, mais douteuse, surtout celui de droite, parceque déja legérement modernisé.

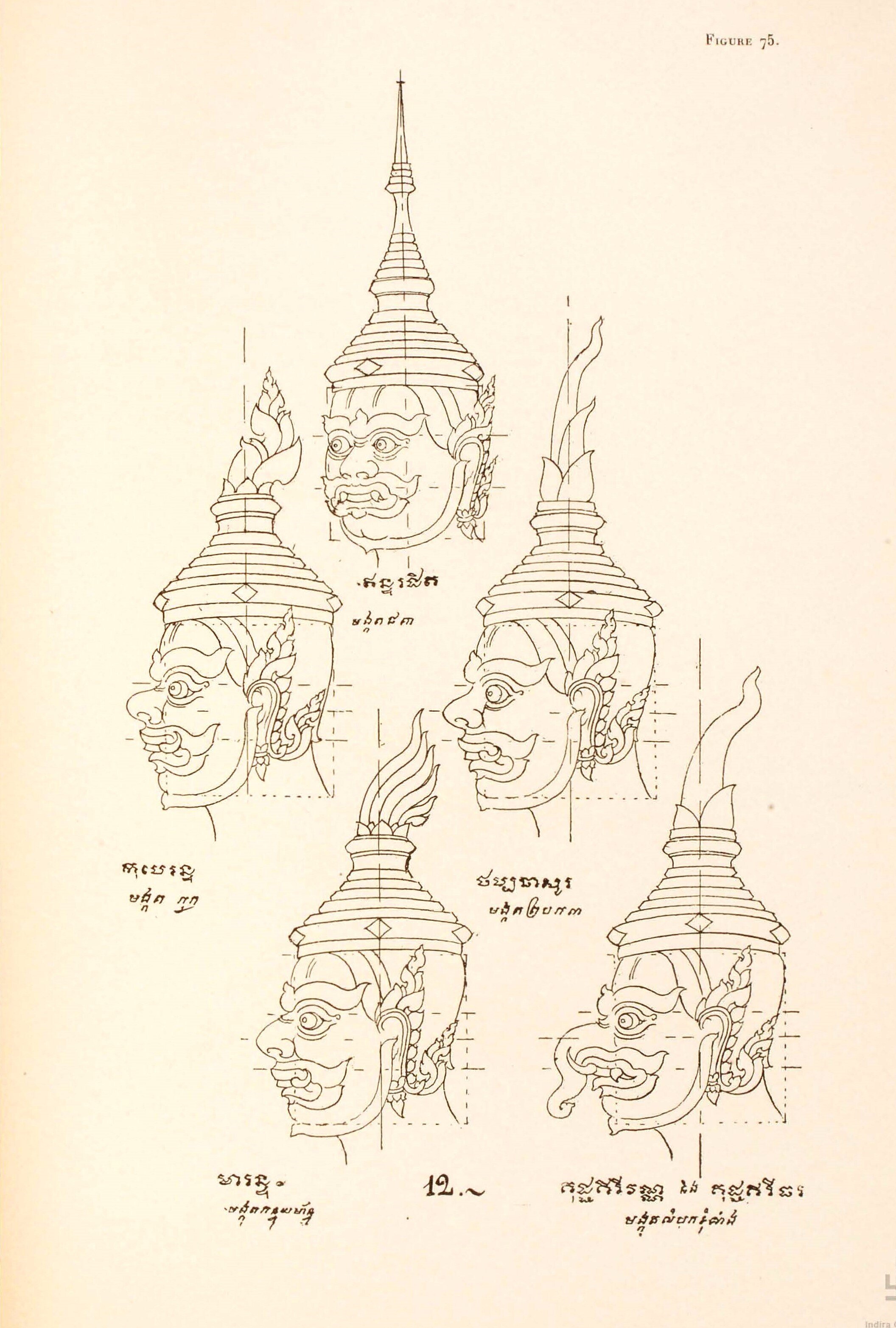

Plate 75 — No. 12. Série de tetes de personnages legendaires: Entochet, Kobéron, Tapanéasaur, Méaron, etc. Chacun est nettement signalé par un détail de la coiffure, sinon du visage.

Plate 76 — No. 13. Nouvelle scene. Ravana donne audience sur son lit d’apparat.

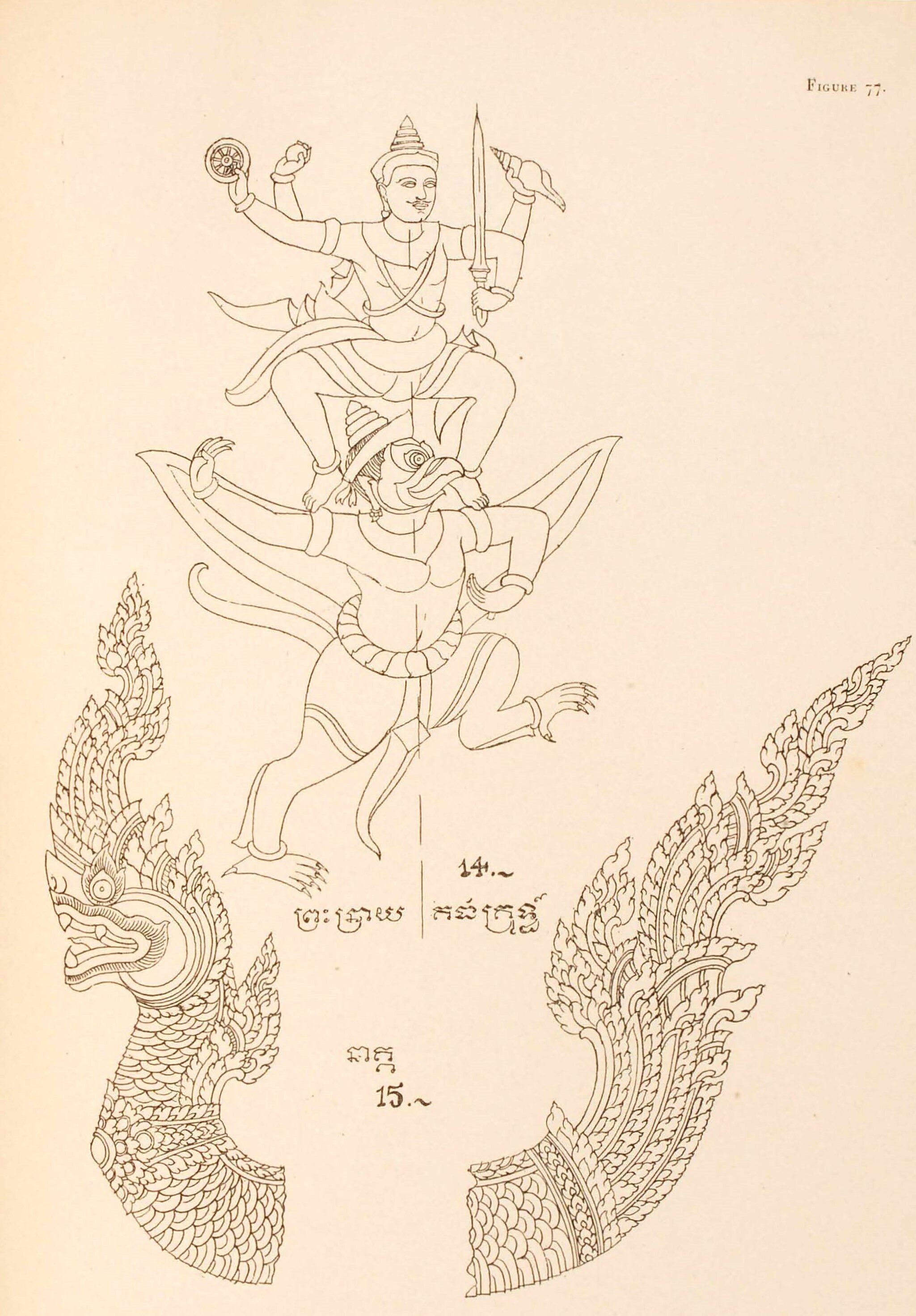

Plate 77 — No. 14. Prah Noréai [Preah Noreay] sur Kruth (Vishnu sur Garuda). Copie de bas-relief exécutée pour nous permettre de lui comparer la composition correspondante contemporaine de la planche suivante, No. 17. | No. 15. Le Naga. Le motif decoratif cher aux Khmers depuis quinze siècles: la tête et la queue.

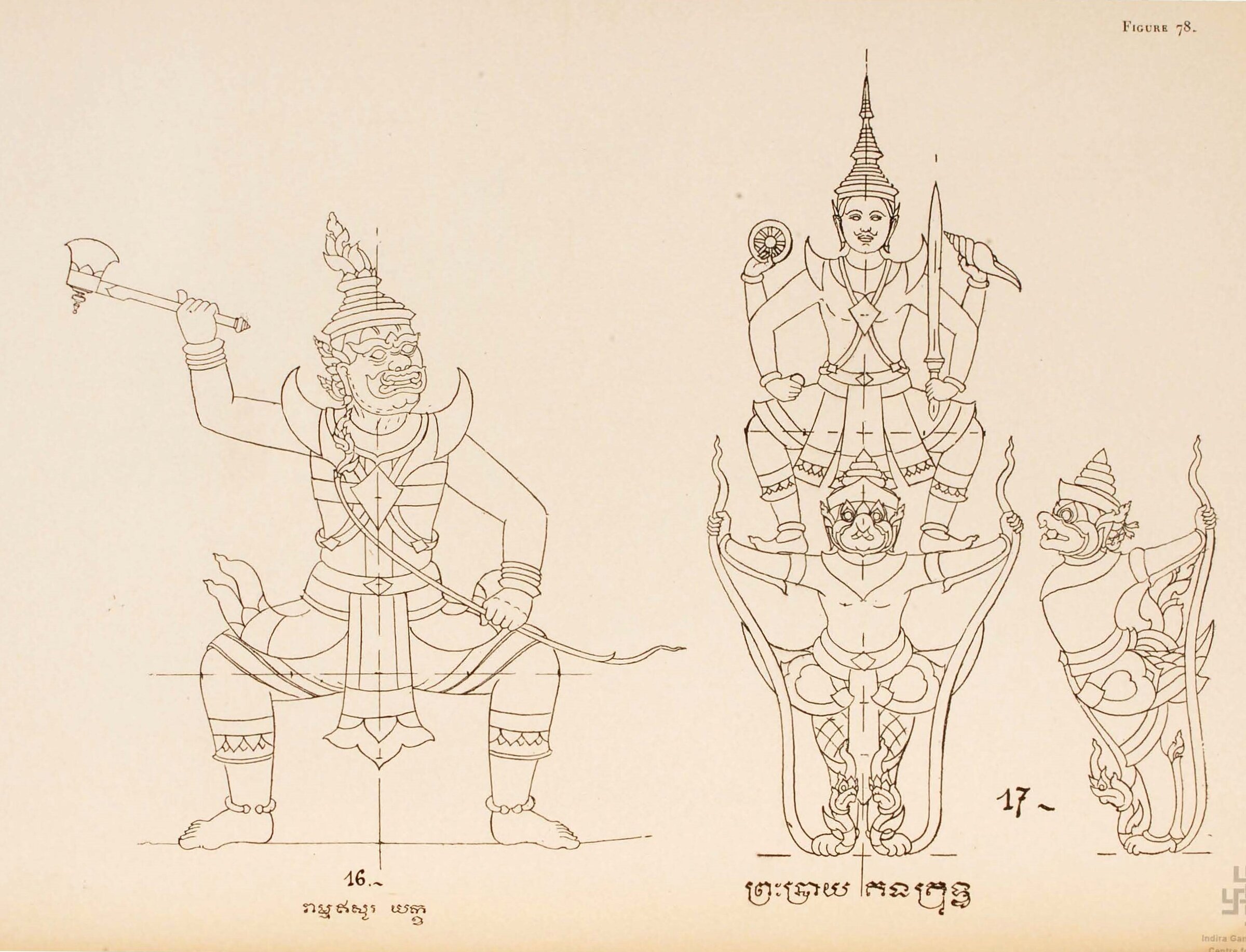

Plate 78 — No. 16. Le roi des Vak dans une attitude de combat. | No. 17. Vishnu sur Garuda.

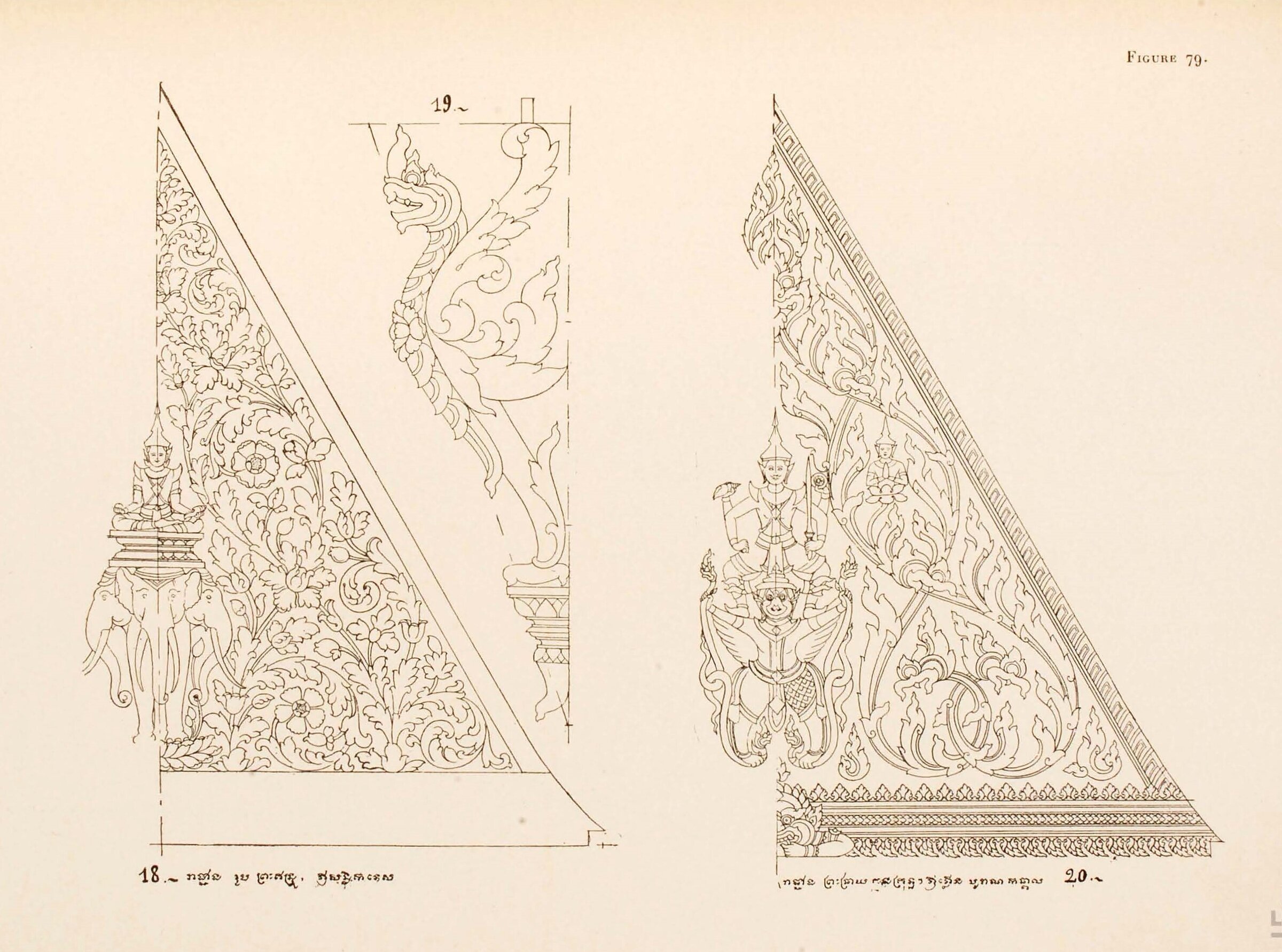

Plate 79 — No. 18. Demi-fronton de pagode portant Prah Entro (Indra) parmi un décor floral. | No. 19. Console: le Garuda stylisé. | No. 20. Même motif architectural que 18, mais portant Vishnu parmi un décor de flammes. La place, l’ordonnance, l’esprit décoratif de cette composition viennent en droite ligne des monuments classiques.

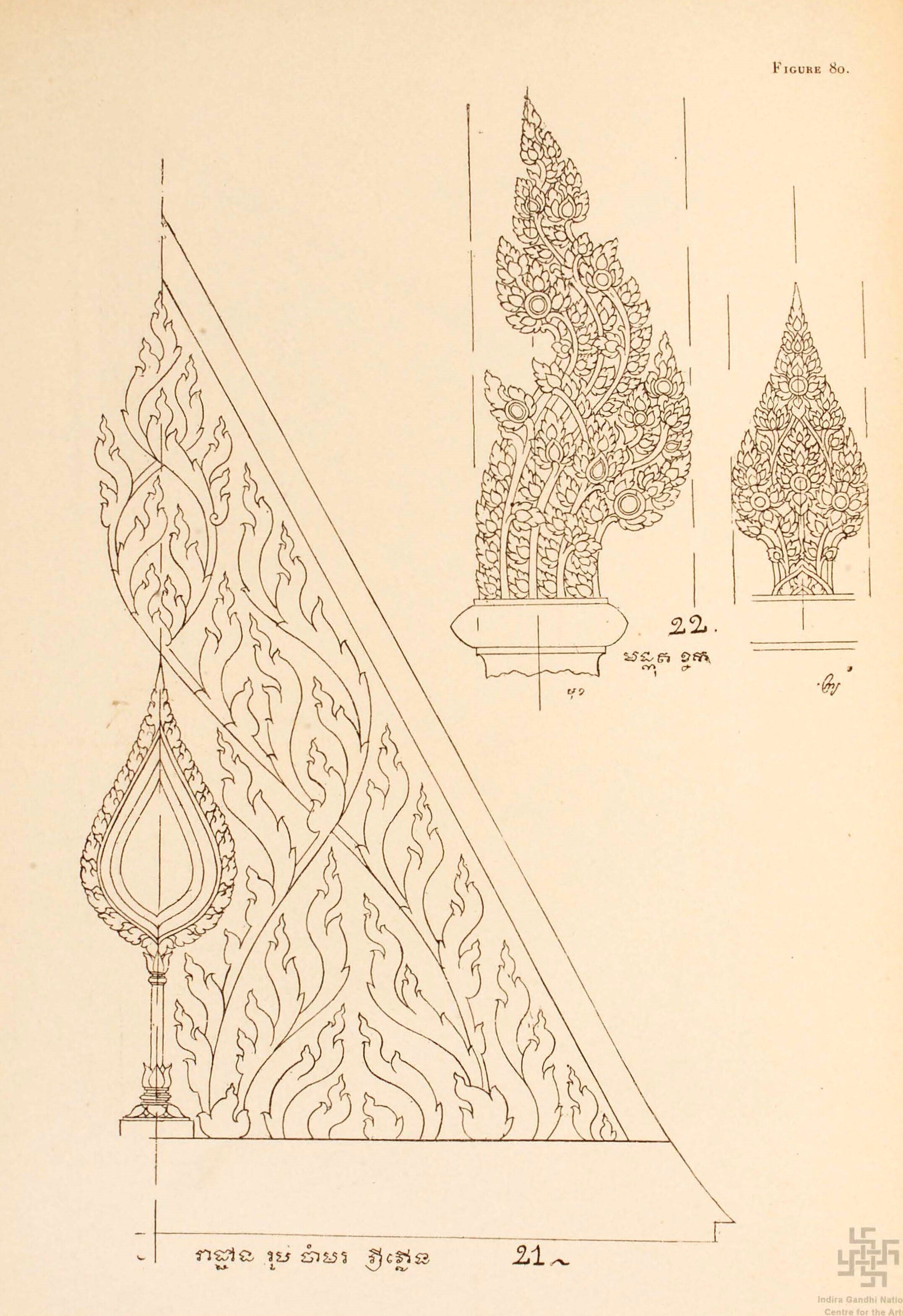

Plate 80 — No. 21. Demi-fronton de pagode: éventail sacerdotal entouré d’un décor de flammes. | No. 22. Nonkot khnok: motif décoratif terminal (face et profil).

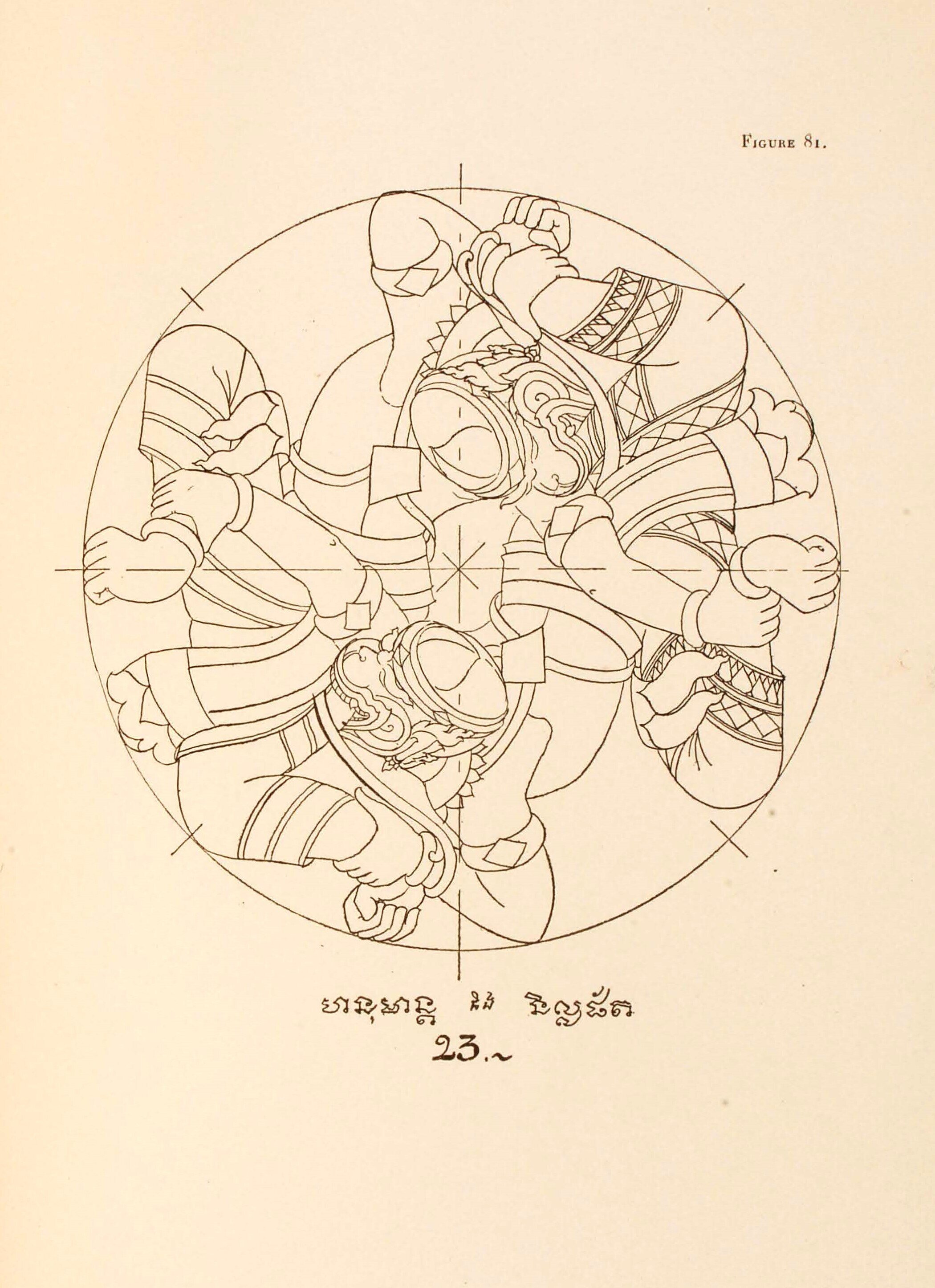

Plate 81 — No. 23. Hanuman et Nélophat: très remarquable composition où la fantaisie décorative khmere apparaît clairement.

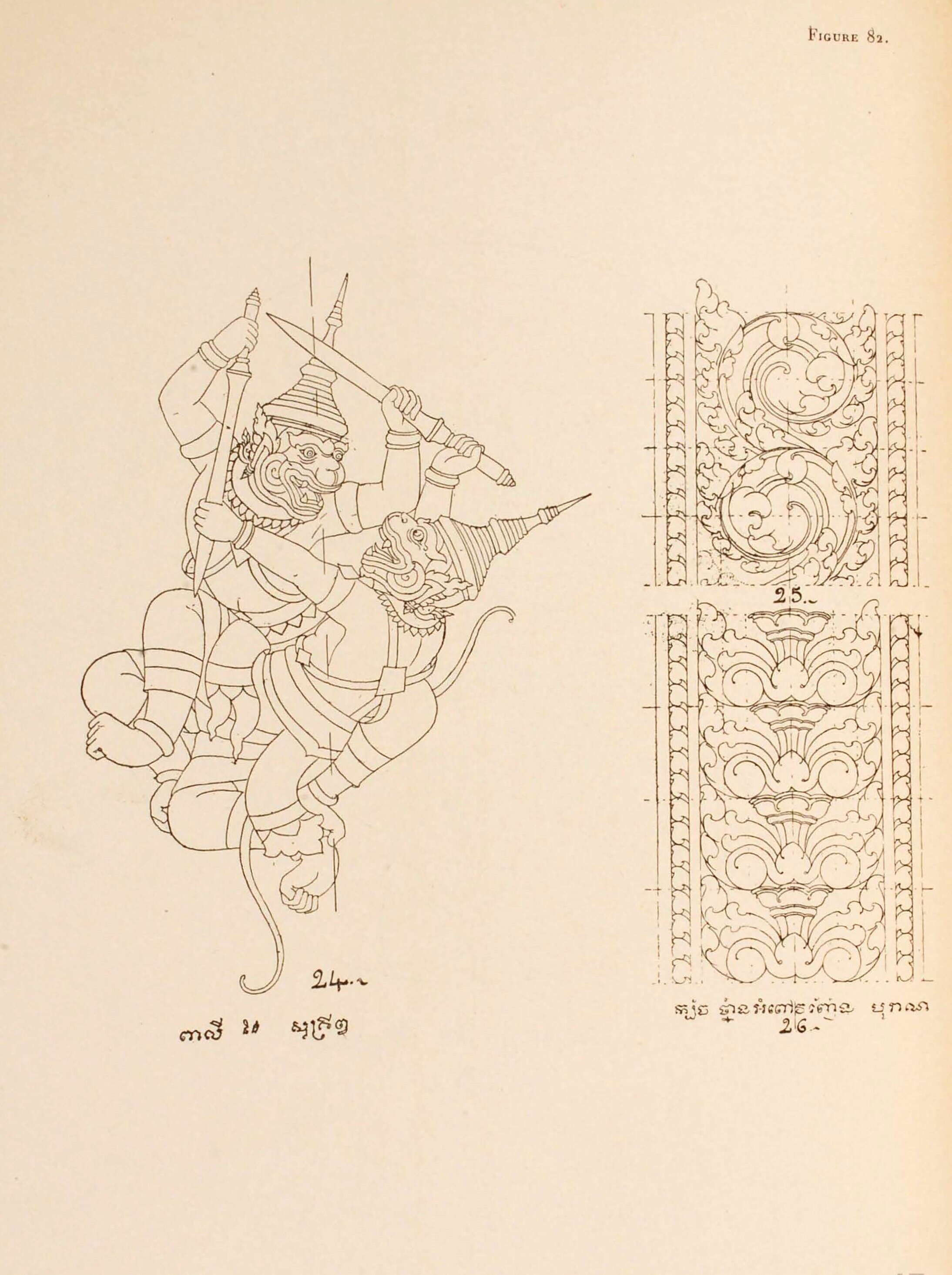

Plate 82 — No. 24. Le duel de Péali et de Sokrip, les deux freres ennemis. | Nos. 25 et 26. Voici deux motifs décoratifs classiques copiés sur les originaux. En haut le rinceau, en bas une composition que les artistes contemporains appellent “en noeuds de canne à sucre”, et tiennent de façon fantaisiste pour un décor de selle à éléphant. L’éléphant étant friand de canne à sucre… il n’y a évidemment qu’un pas à faire pour établir le rapprochement. Mais il faut se défier serieusement des rapprochements khmers.

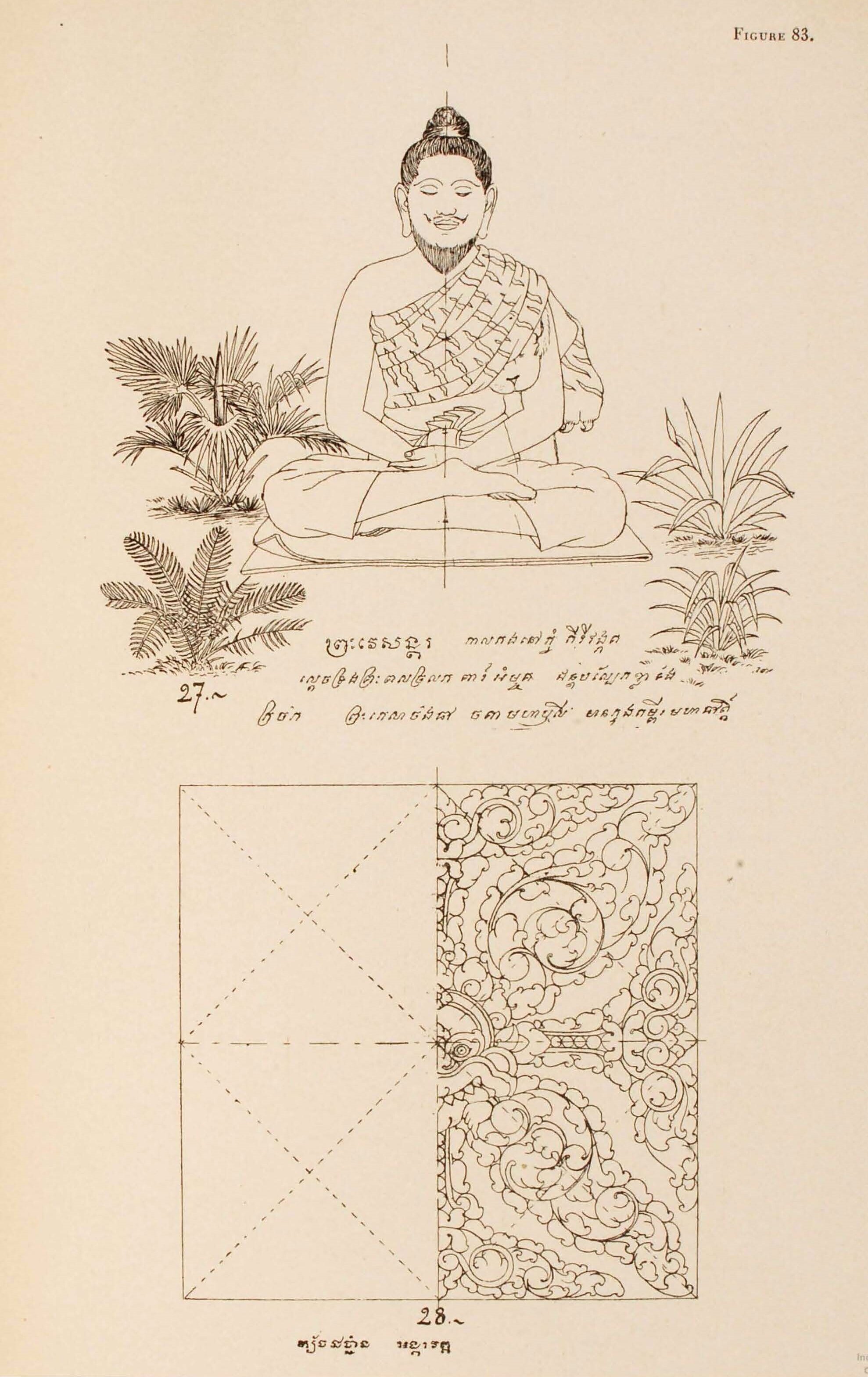

Plate 83 — No. 27. Prah Vésandar méditant dans l’ascétisme, une peau de tigre en écharpe. | No. 28. Copie d’un décor de muraille d’Angkor Vat.

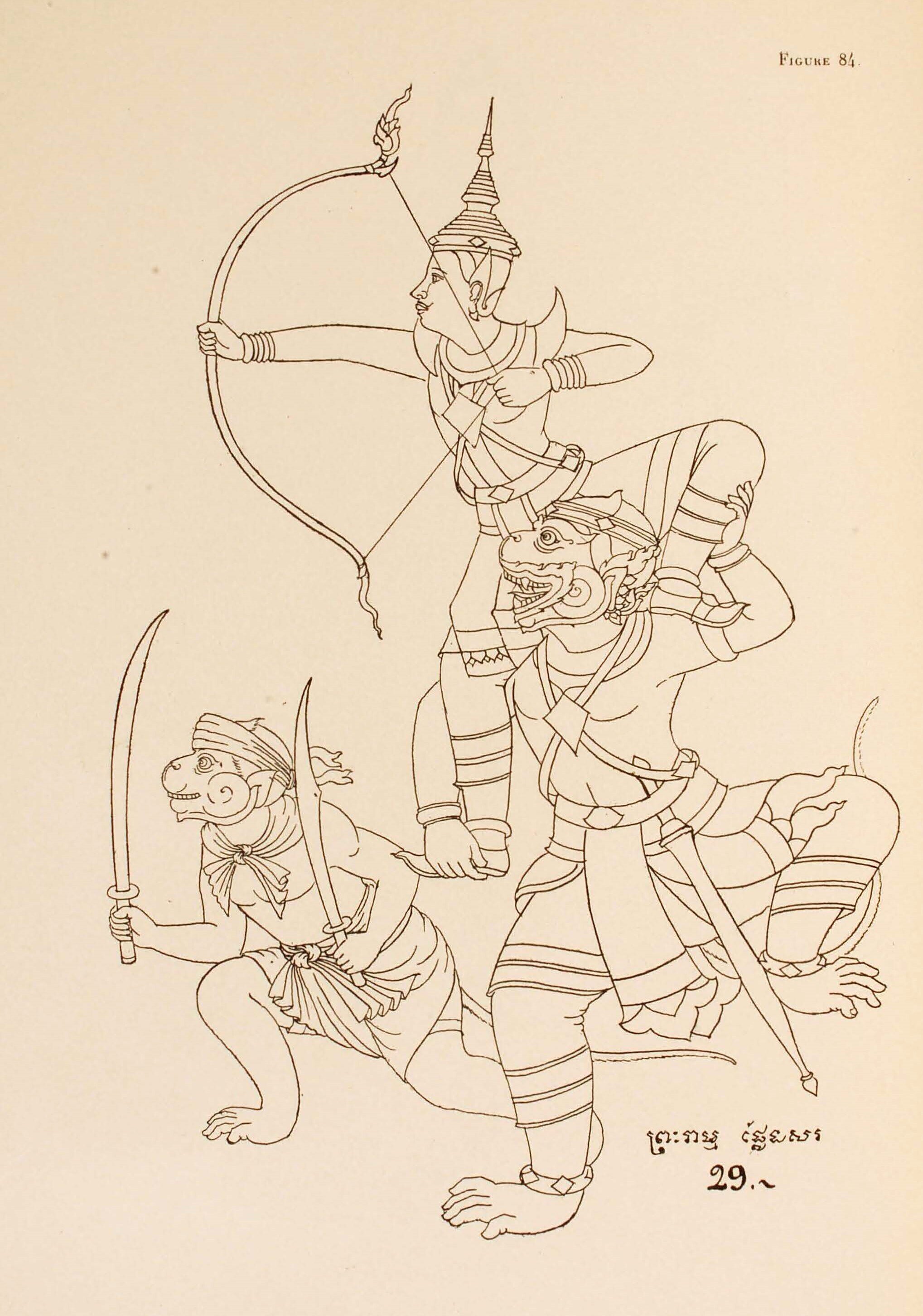

Plate 84 — No. 29. Rama transporté par Hanuman, tirant de l’arc au cours de sa lutte furieuse contre Ravana. A gauche, un singe guerrier.

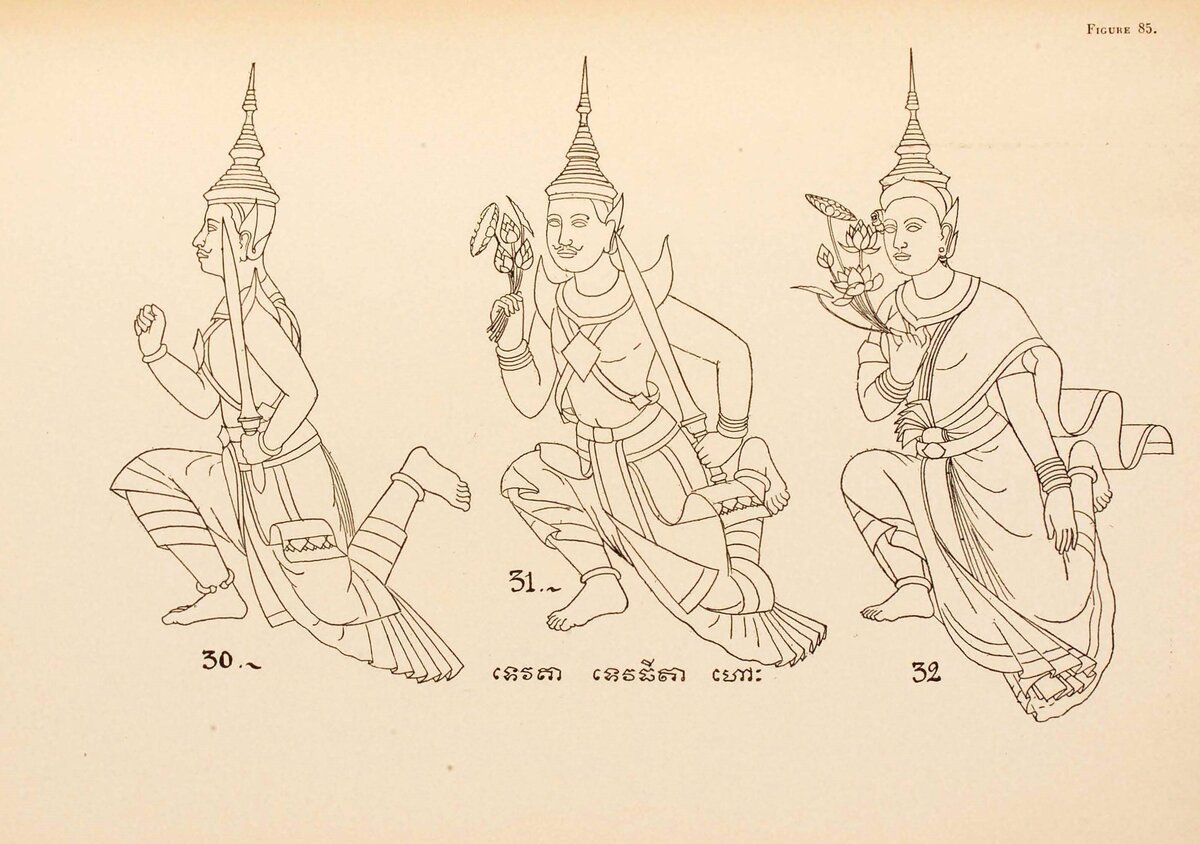

Plate 85 — Nos. 30, 31, 32. Tévoda, Tévothida volant: les gracieux génies masculins et féminins de l’air, l’ange khmer. Cette pose sur le genou et pied levé est depuis le IXeme siecle celle des personnages circulant dans les airs, quittant le sol.

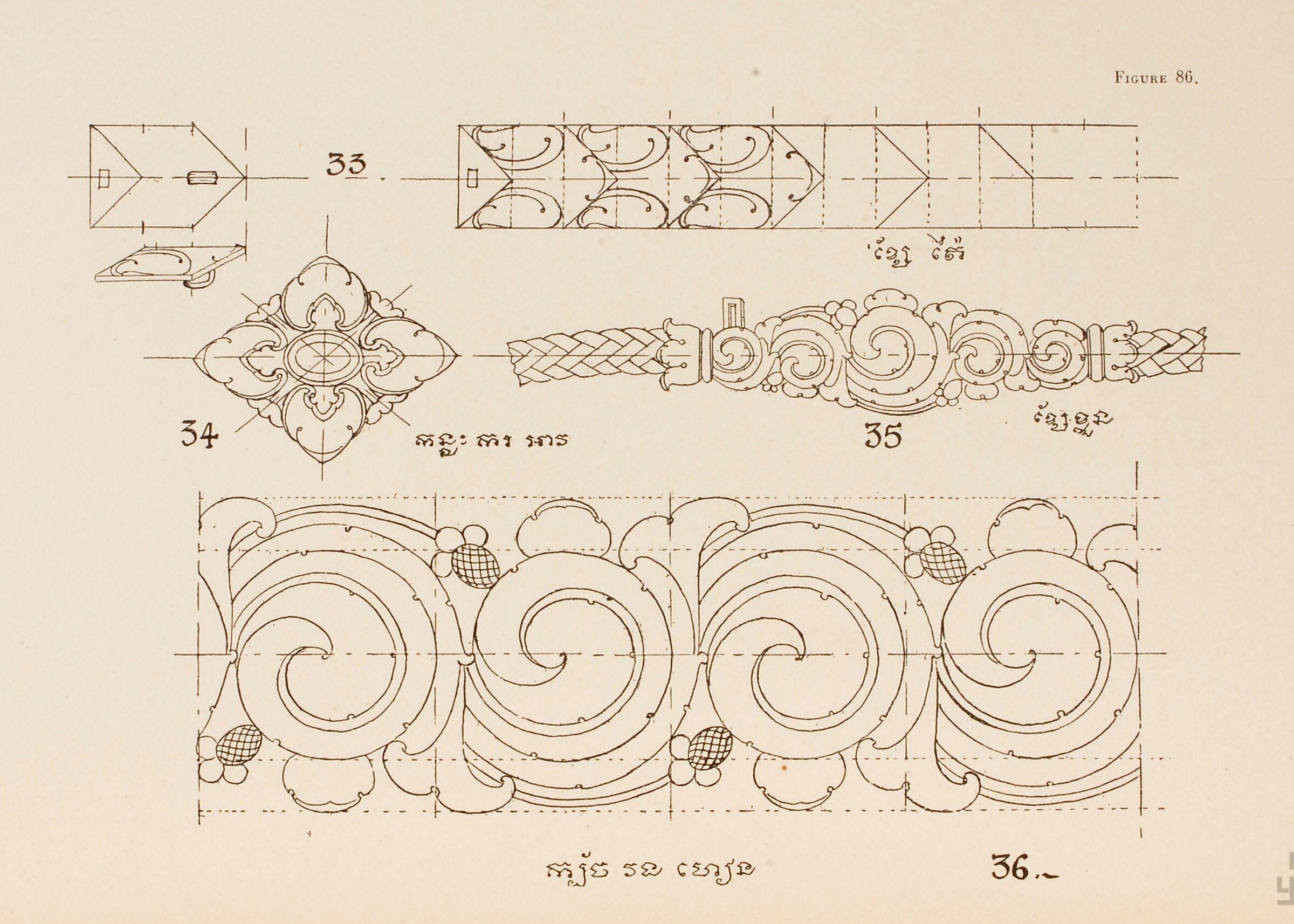

Plate 86 — Nos. 33 – 36. Copie de bracelets, plaques de sautoir el ceinture de l’art classique conservés au Musée A. Sarraut. 36 est l’application à plat du motif 35 exécuté en relief.

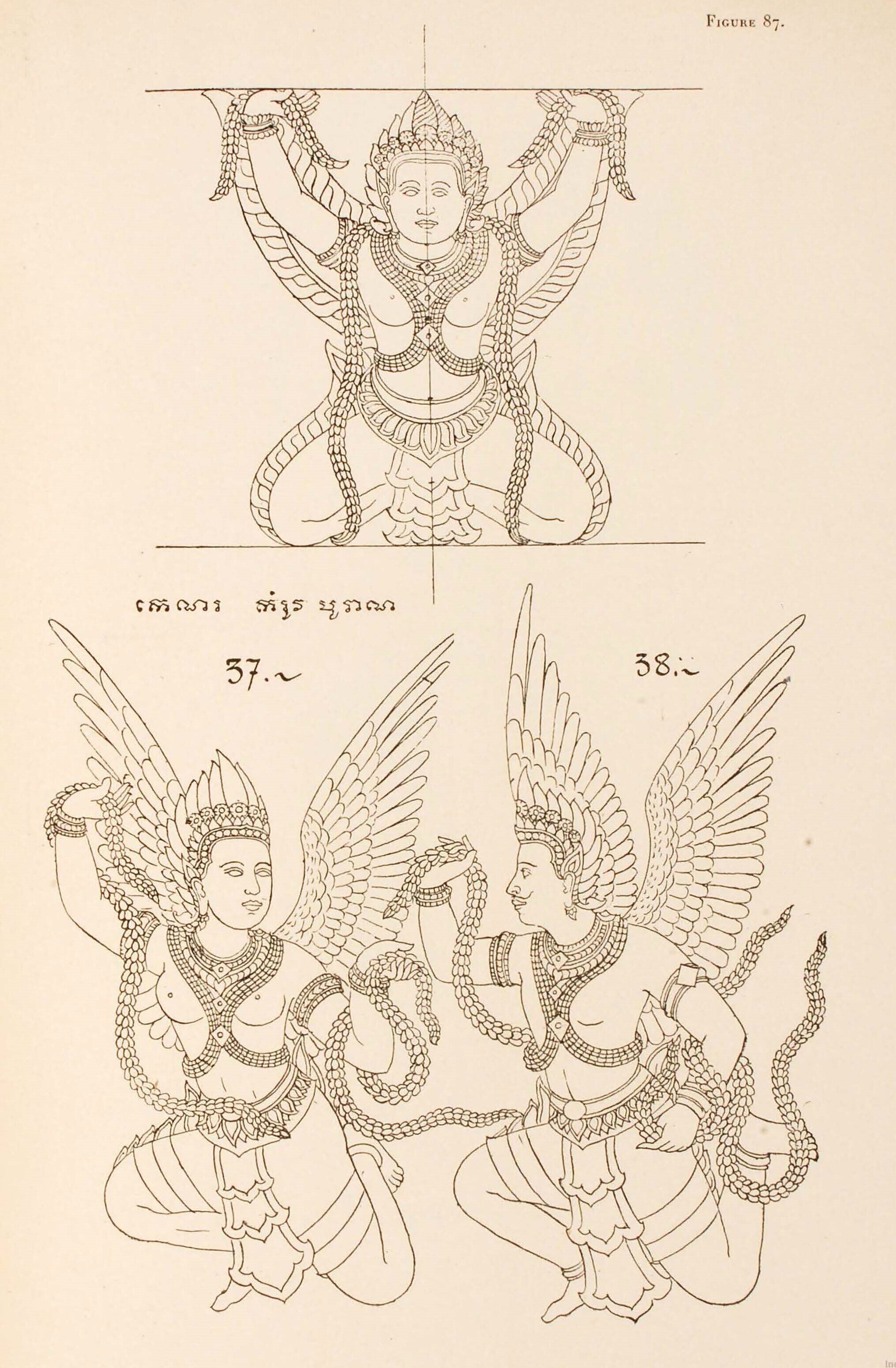

Plate 87 — Nos. 37 et 38. Kénar: nymphes et génies volants, mélange de sculpture classique et de détails contemportains.

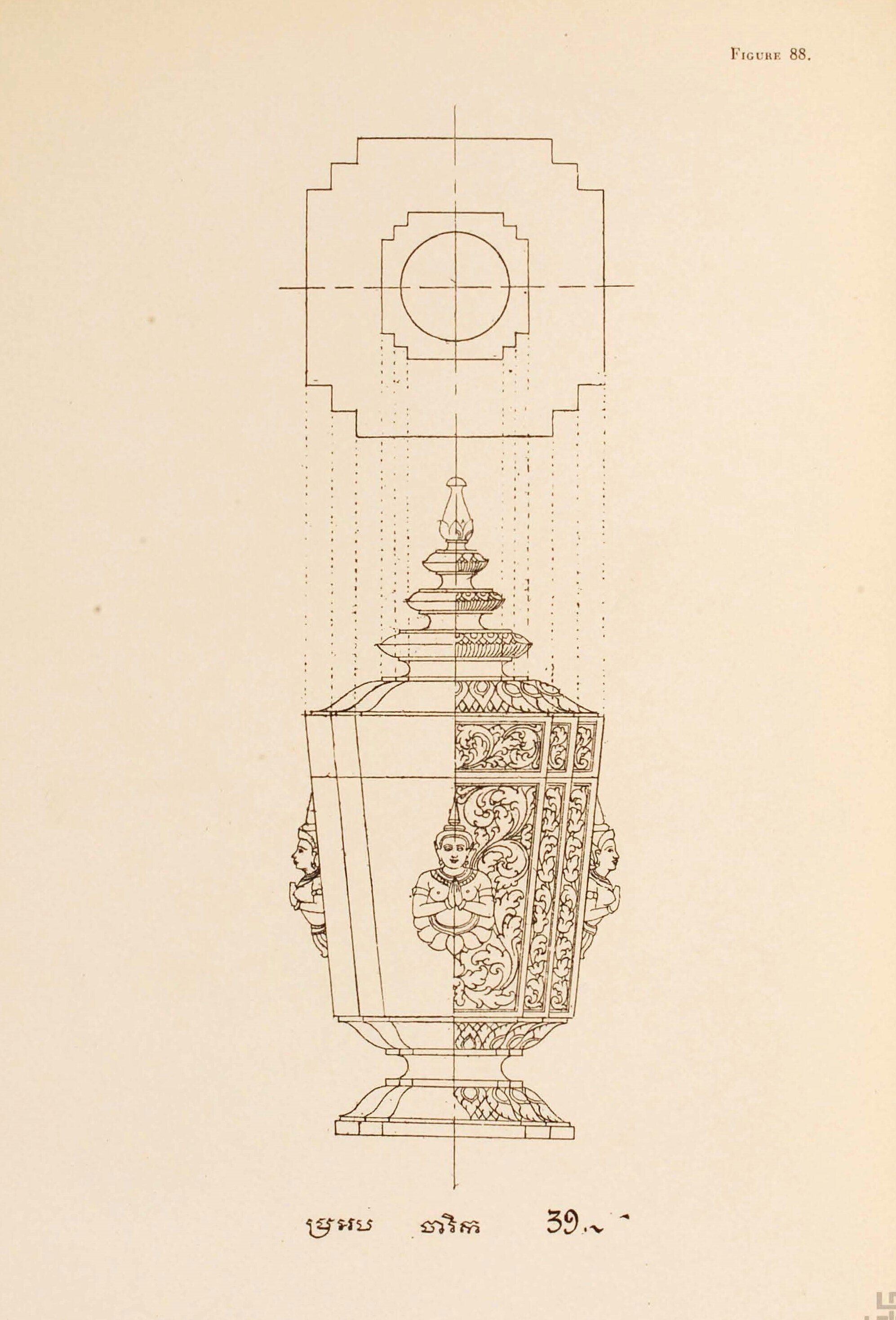

Plate 88 — No. 39. Boîte “charék” en forme de borne. Composition sur un thème donné pour etre exécutée en argent embouti et repoussé. Mélange de personnages d’allure classique à un décor contemporain.

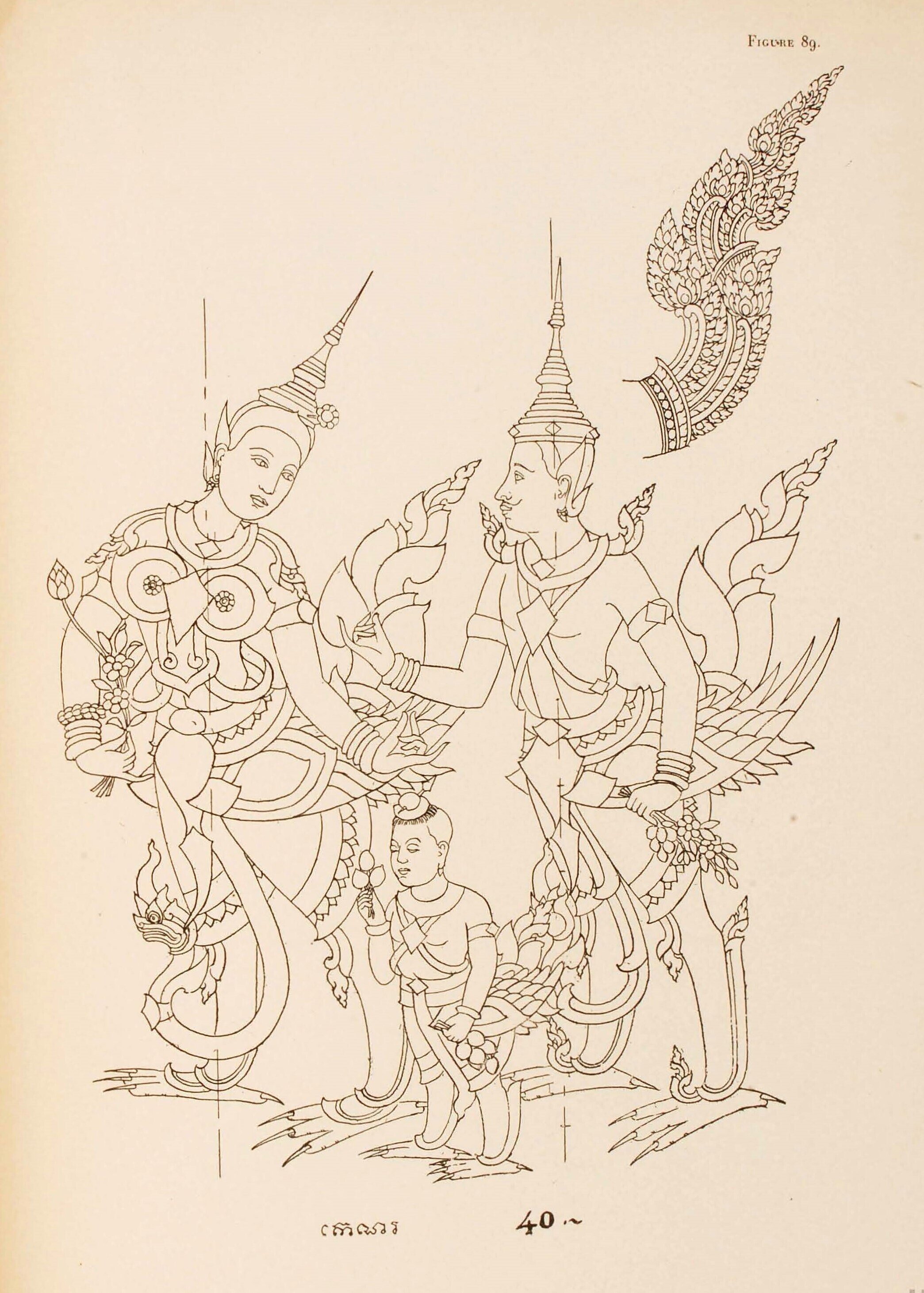

Plate 89 — No. 40. Kénar. Toute une famille de ces personnages ailés que nous avons vus sous leur forme presque classique aux figures 33 à 36, et qui sont ici revêtus de leur costume nettement contemporain. L’actrice qui tient ce role dans un ballet n’est pas vêtue autrement.

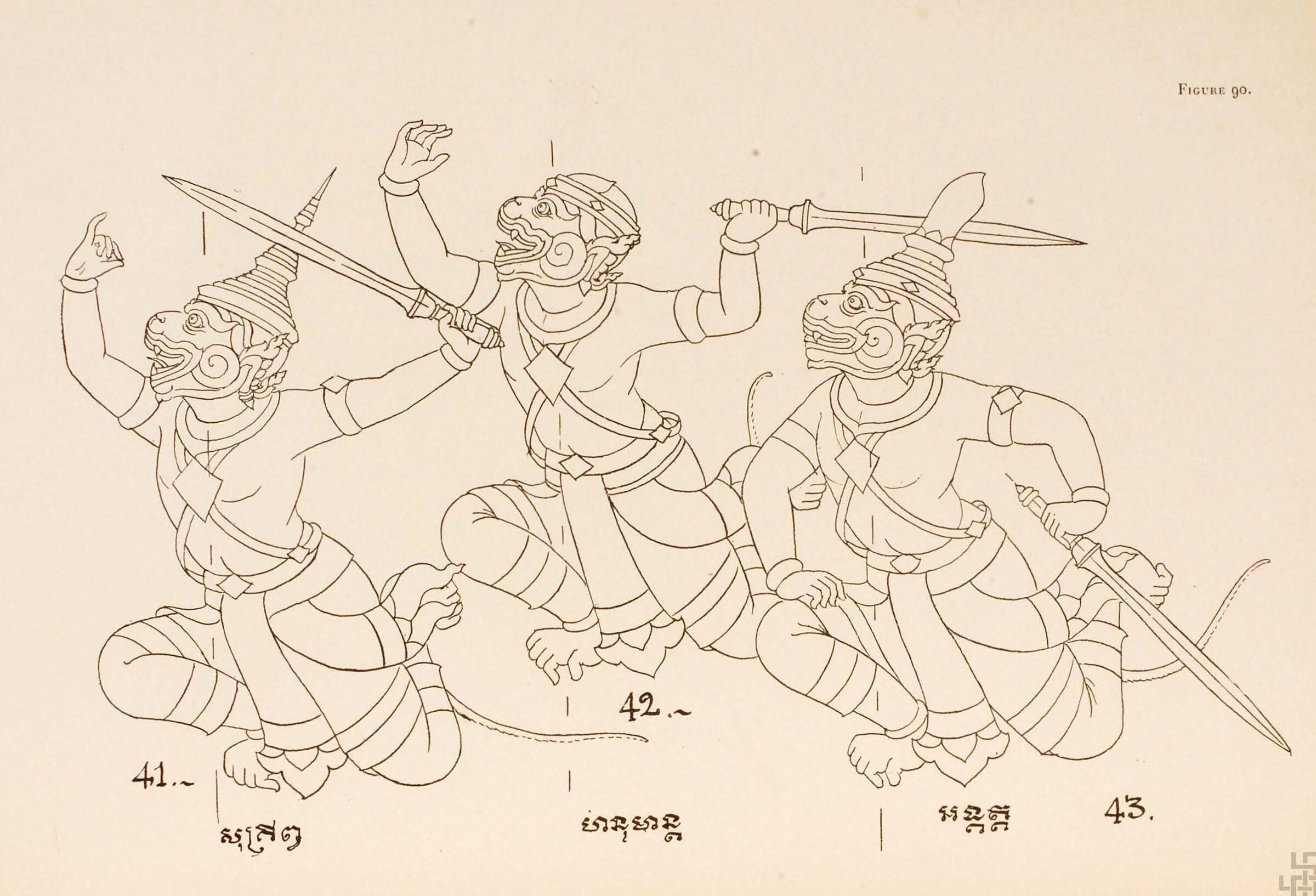

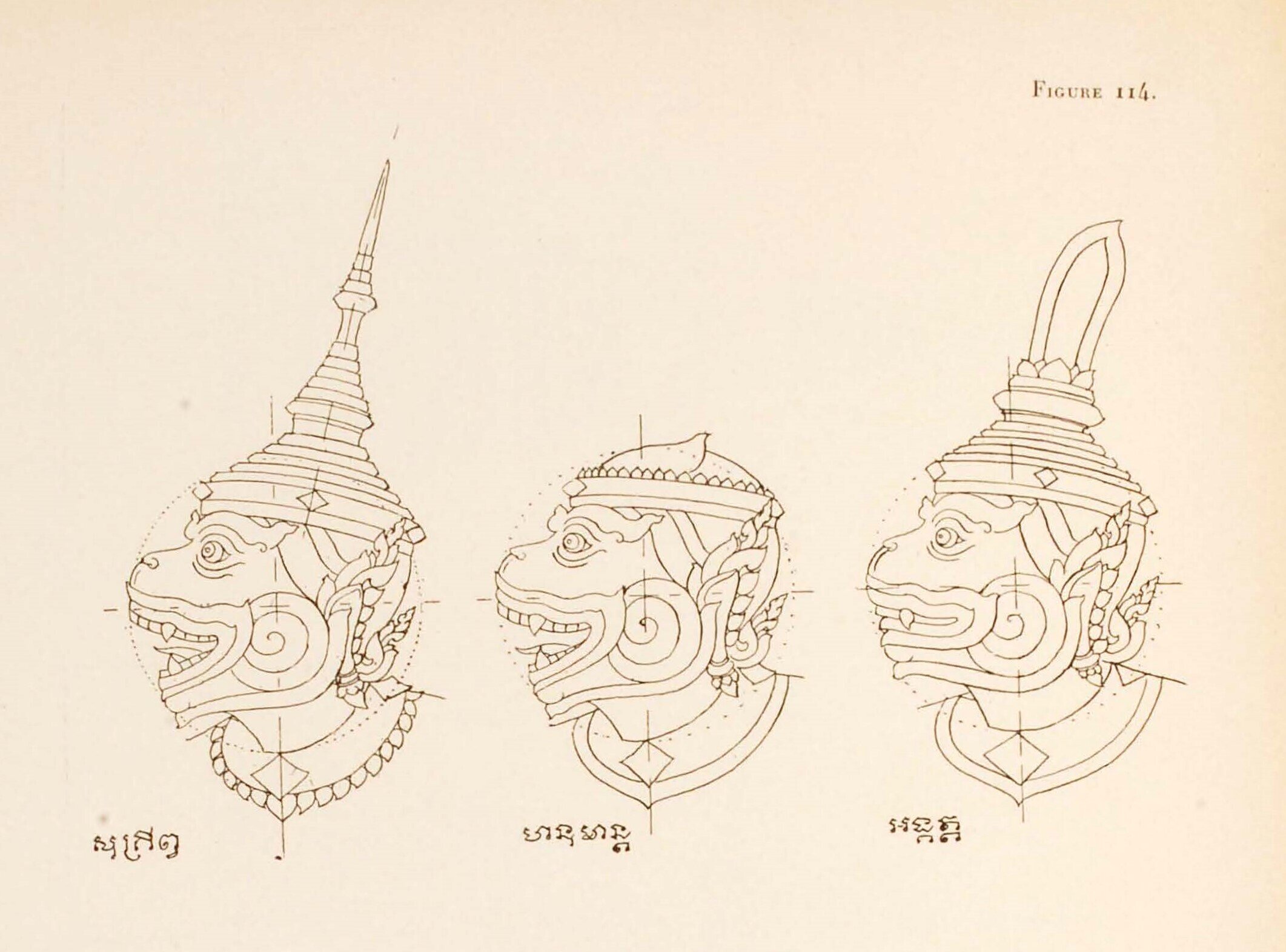

Plate 90 — Nos. 41−42−43. Les trois singes dont les détails de la tête sont étudiés fig 114 sont ici représentés en entier dans des poses de combat.

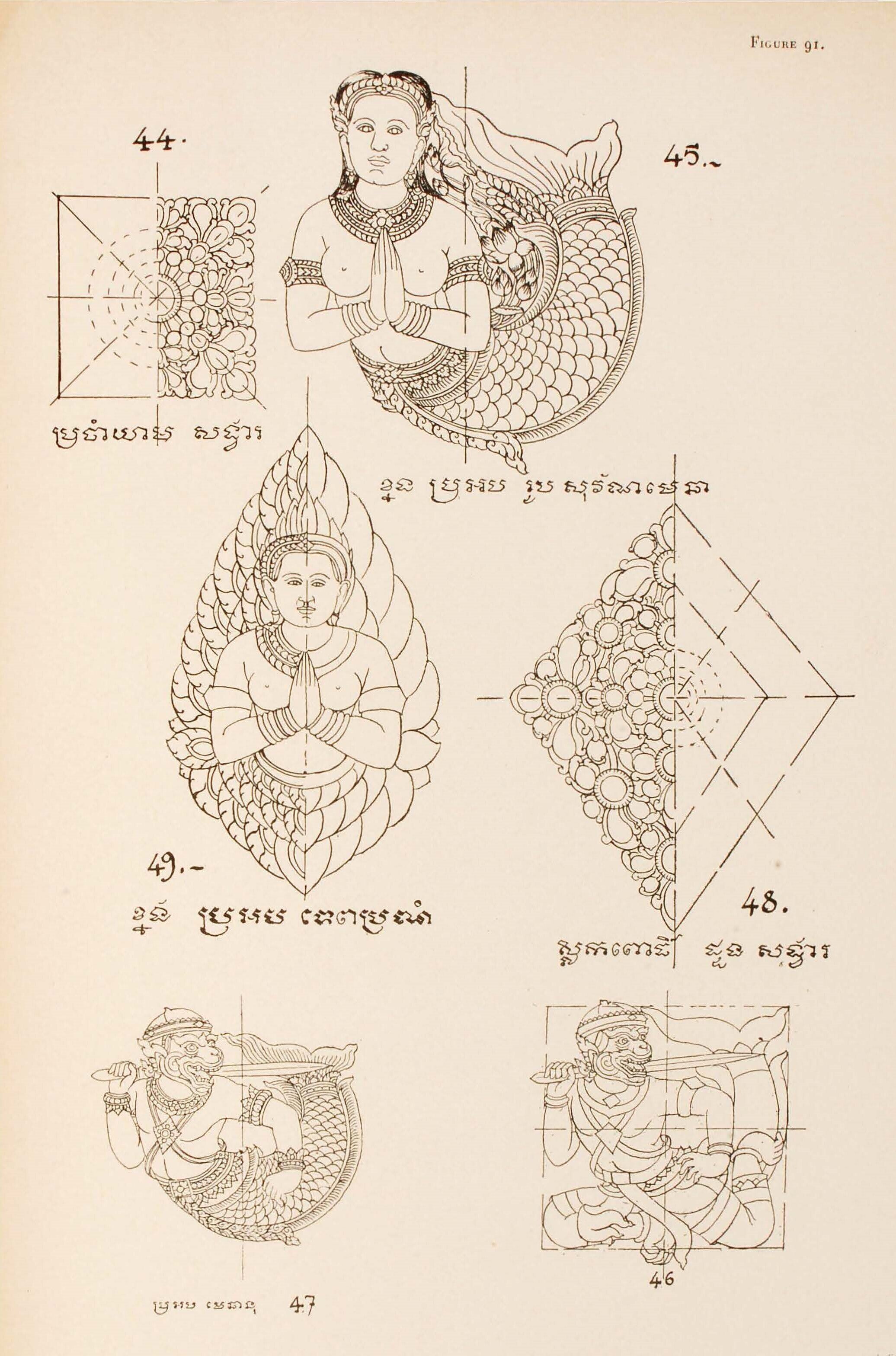

Plate 91– Nos 44 et 48. Détails du décor des plaques ornementales on orfevrerie de baudrier princier. | No. 45. Boîte ornée de la figuration de Sovanméchéa | Nos. 46 et 47, boîte “méchéan“et 49, boîte “Tep Pramam”. Ces boîtes populaires, en argent et or repoussés, servent à mettre le tabac. On y voit représentés divers héros hybrides de la légende khmère.

Plate 92 — No. 50. Le Garuda copié sur le bas-relief angkorien est tel qu’il est figuré dans les enluminures actuelles.

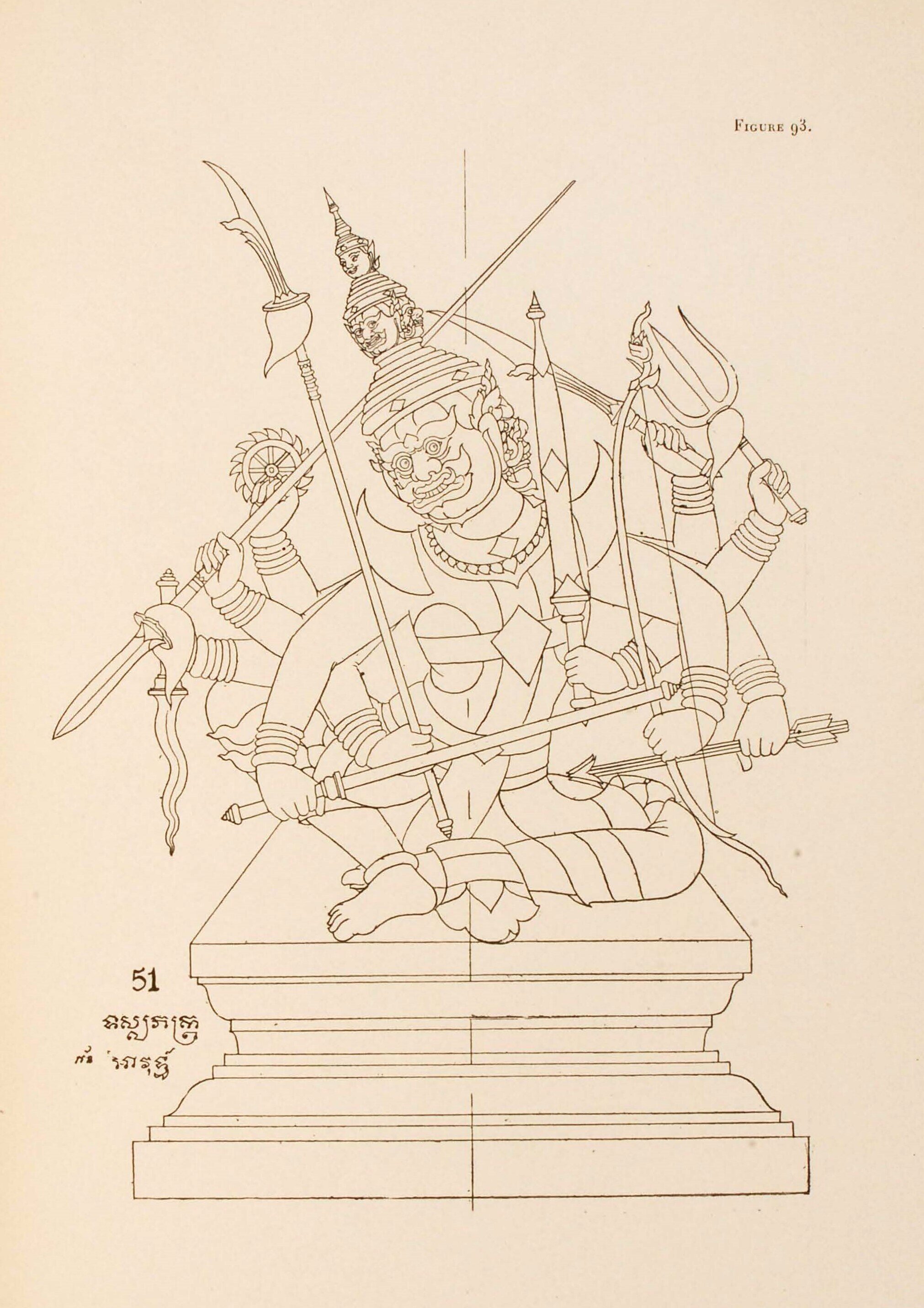

Plate 93 — No. 51. Tosaphakr et tous ses attributs.

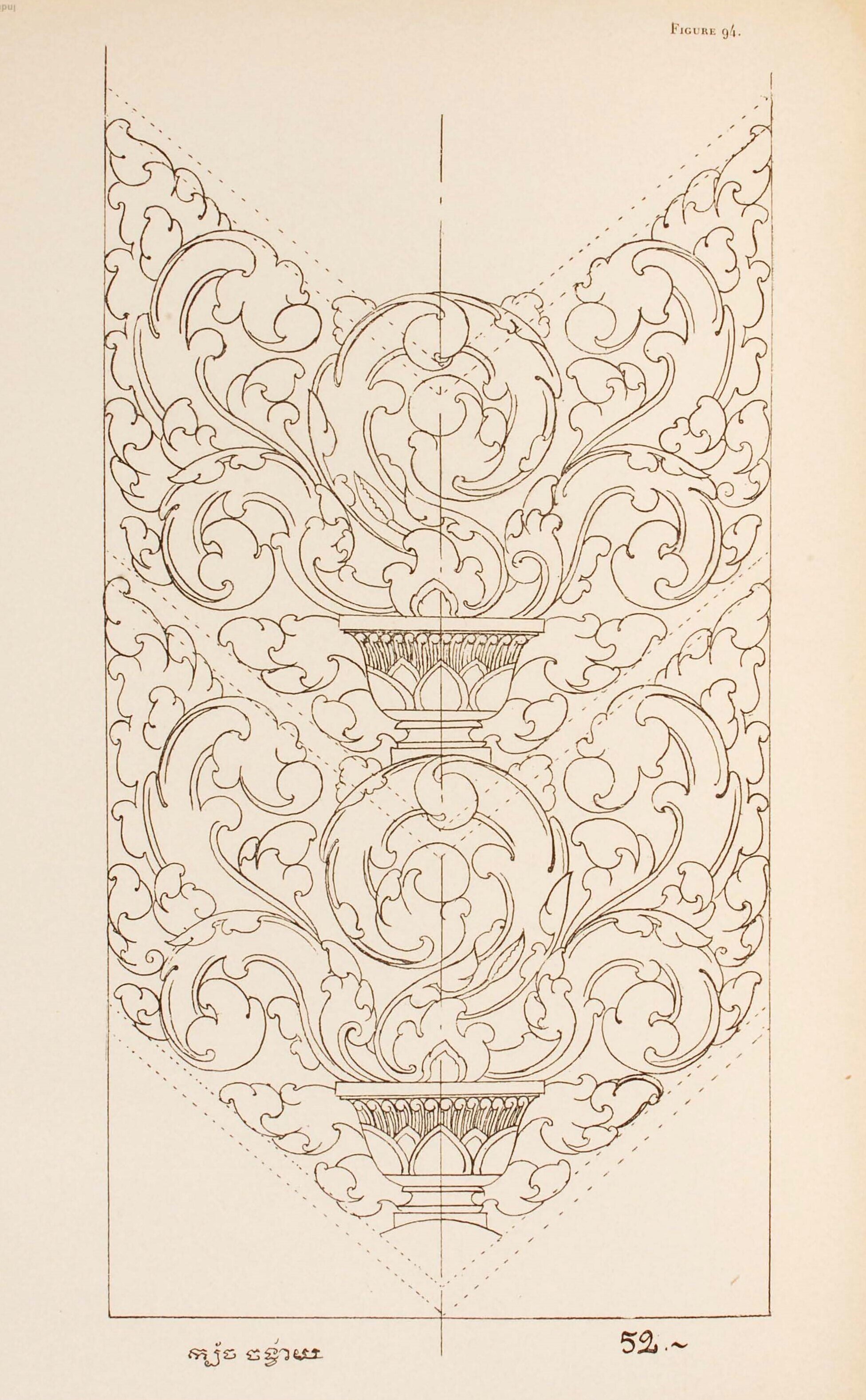

Plate 94 — No. 52. Copie de sculpture classique de panneau de fausse porte.

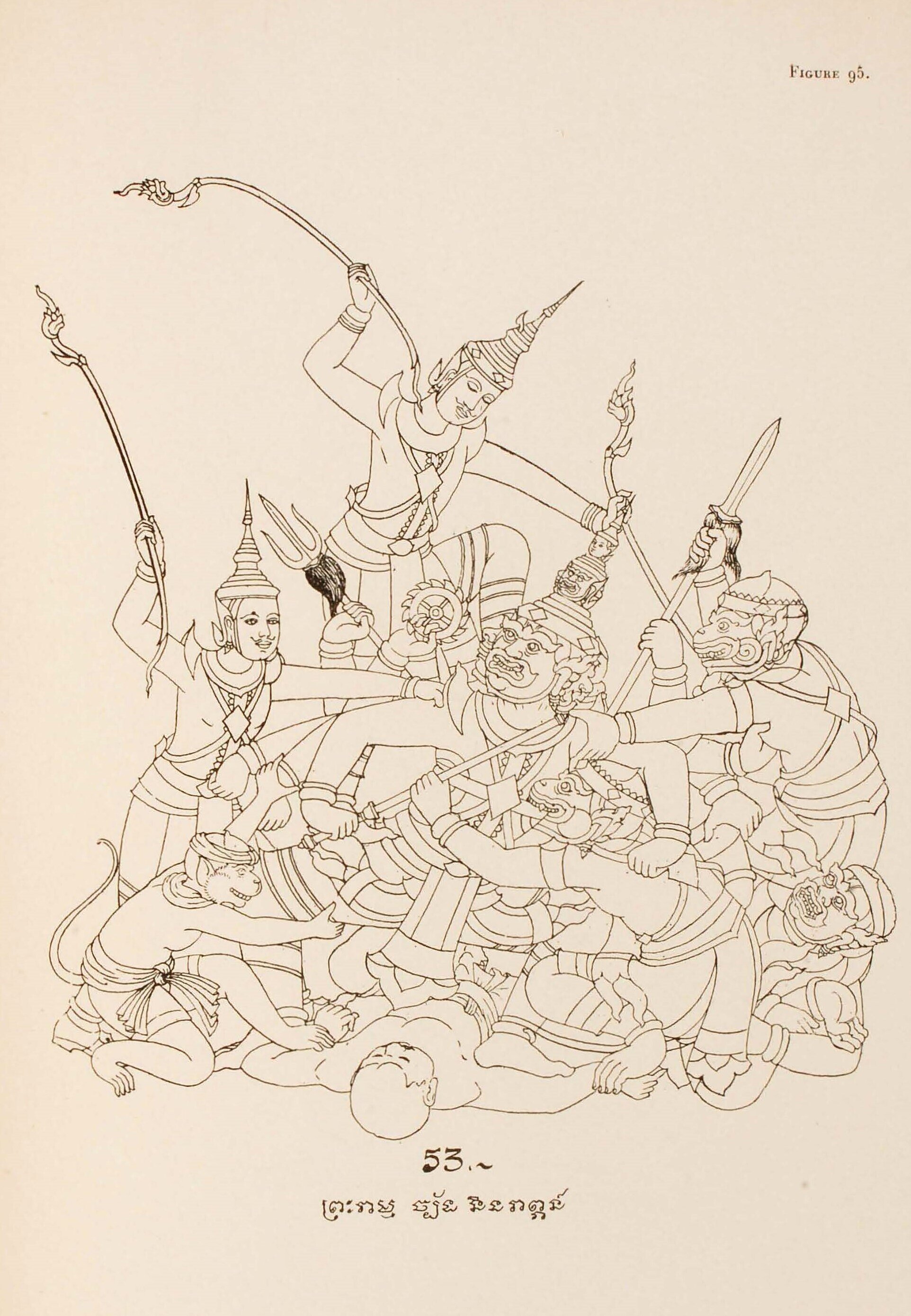

Plate 95 — No. 53. Grande scène de combat où Rama triomphe enfin de Ravana.

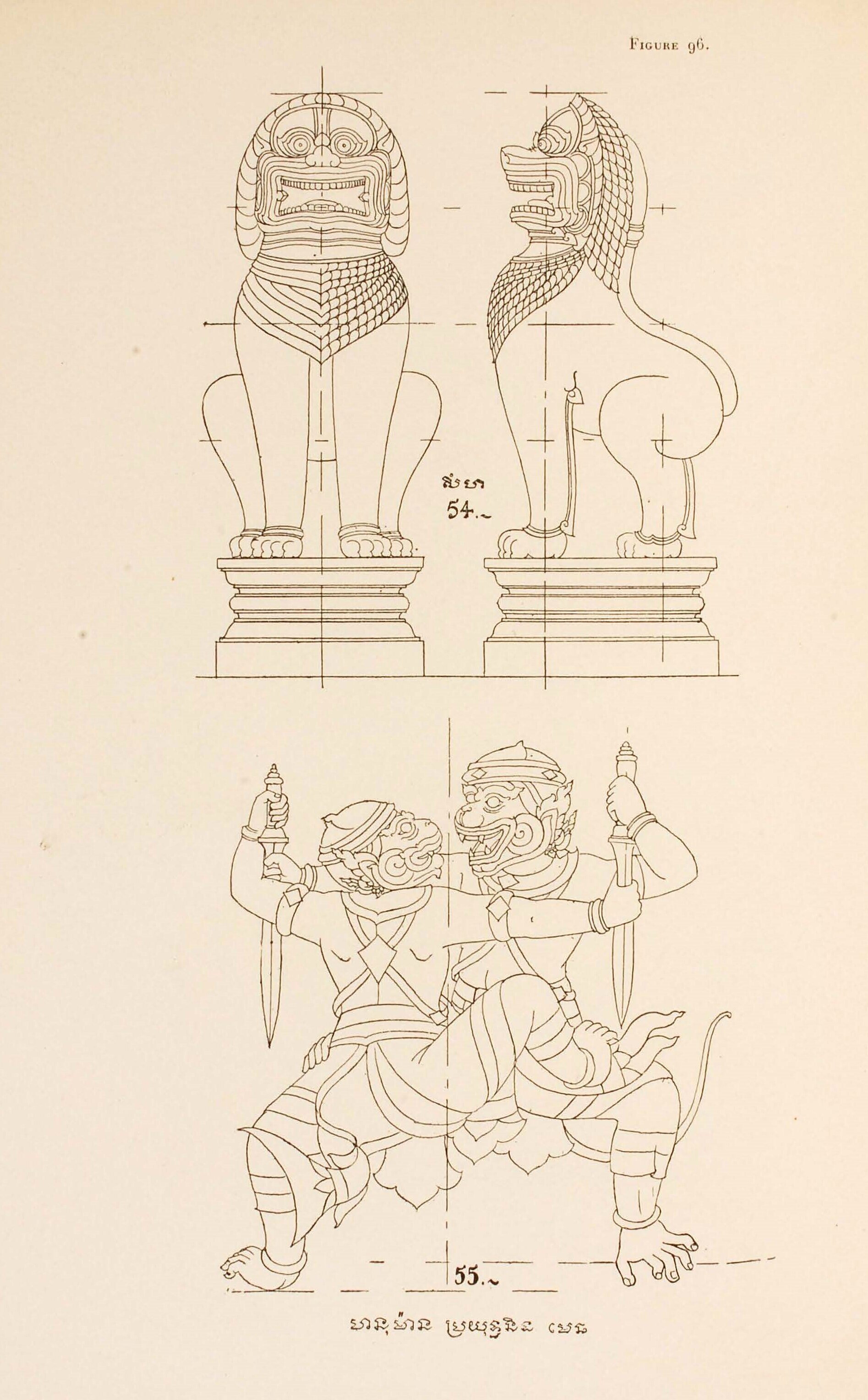

Plate 96 — No. 54. Lion. Dessin inspiré de la ronde bosse classique. Lutte de Hanuman et Méchan, variante des scenes de duel des fig. 81, 82.

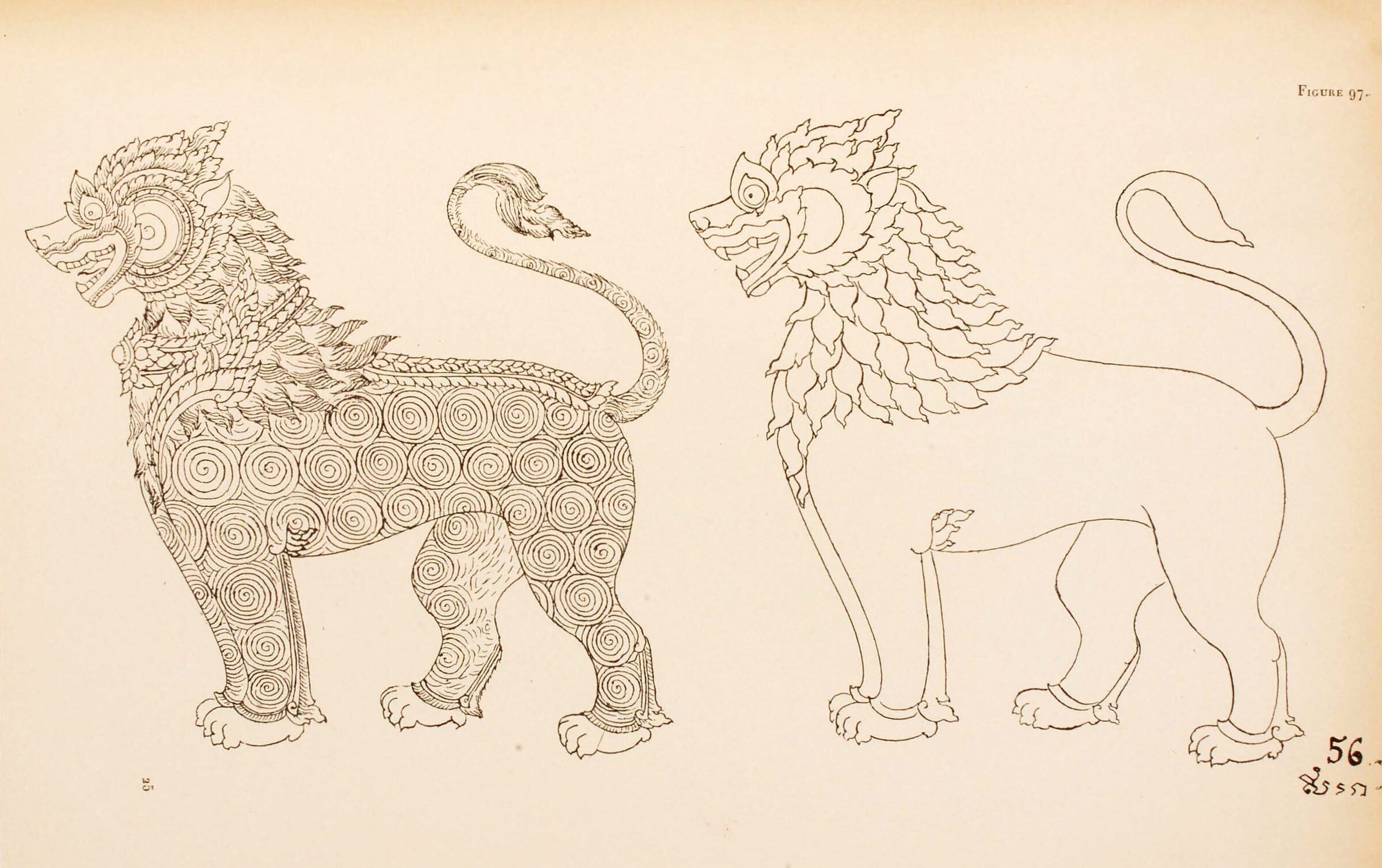

Plate 97 — No. 56. Le lion moderne.

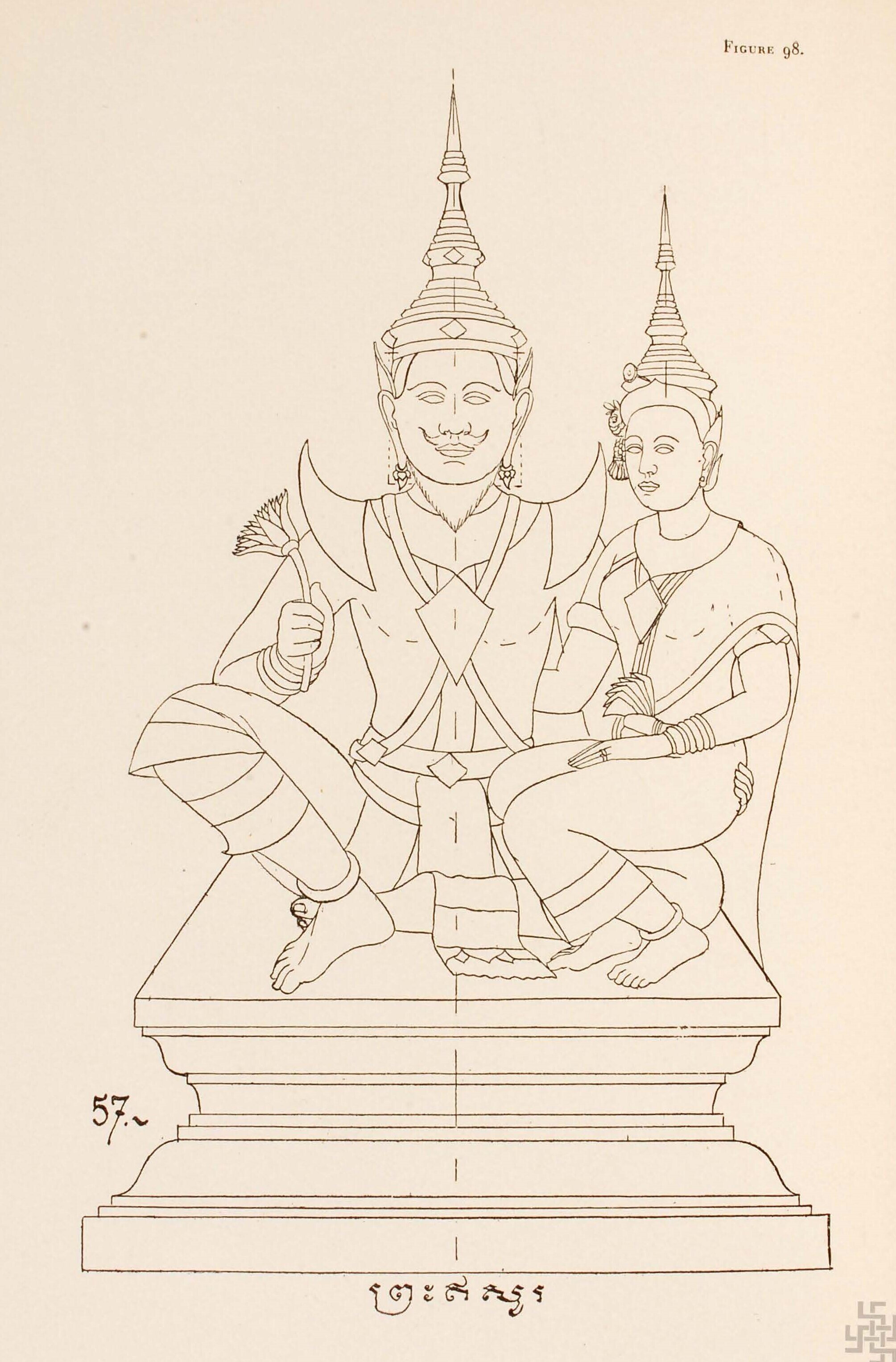

Plate 98 — No. 57. Prah Eisaur: Çiva. Ce groupe est inspiré d’une statue de Çiva et de sa Çakti de l’époque classique conservée au Musée Albert Sarraut. L’artiste s’est borné a habiller ces divinites au goût du jour.

Plate 99 — No. 58. Décor d’extremités de lit royal dit “mondap”. Stylisation de queue de Naga flamboyante.

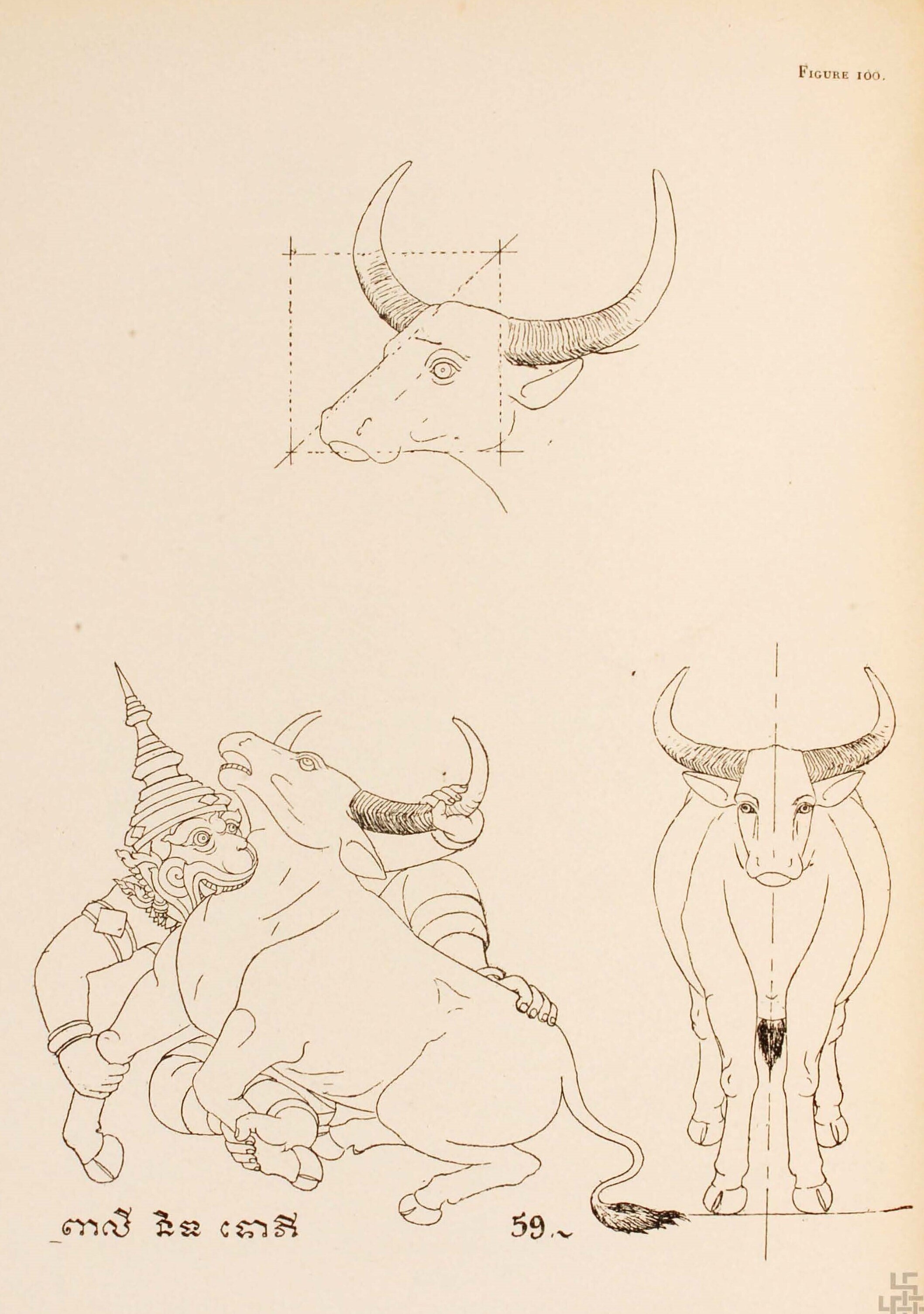

Plate 100 — No. 59. Péali et le bufle Topi. Le stylisation de l’animal né parvient pas à lui retirer un certain aspect naturaliste extrêmement bien observé.

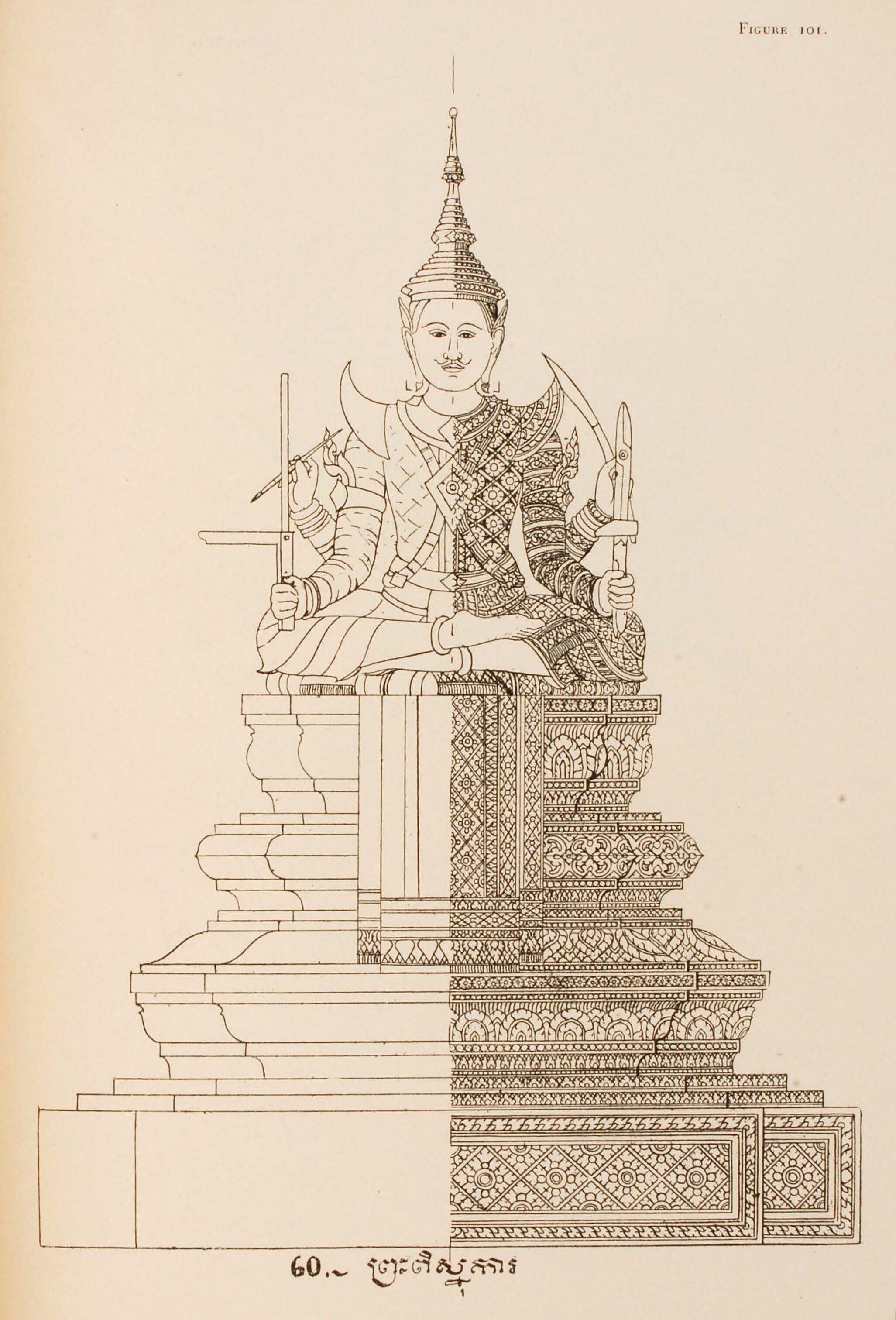

Plate 101 — No. 60. Prah Pisnukar, l’architecte divin, grand patron des artisans Certains decors du socle pourraient être juxtaposés à des motifs classiques,

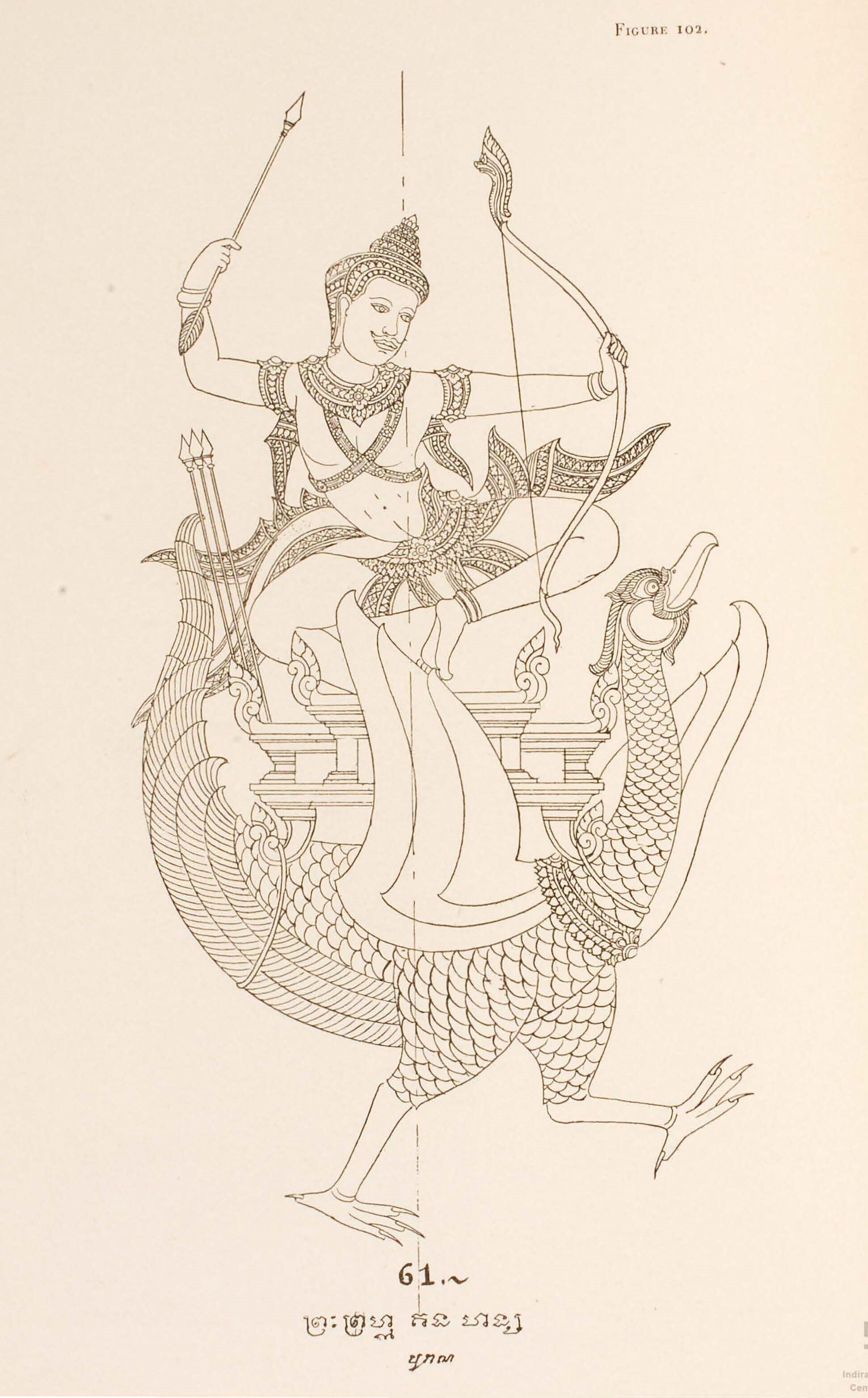

Plate 102 — No. 61. Prah Prom sur Hangs (Brahma sur Hamsa). Autre copie d’un bas-relief d’Angkor Vat. Voir la même scene fig 106.

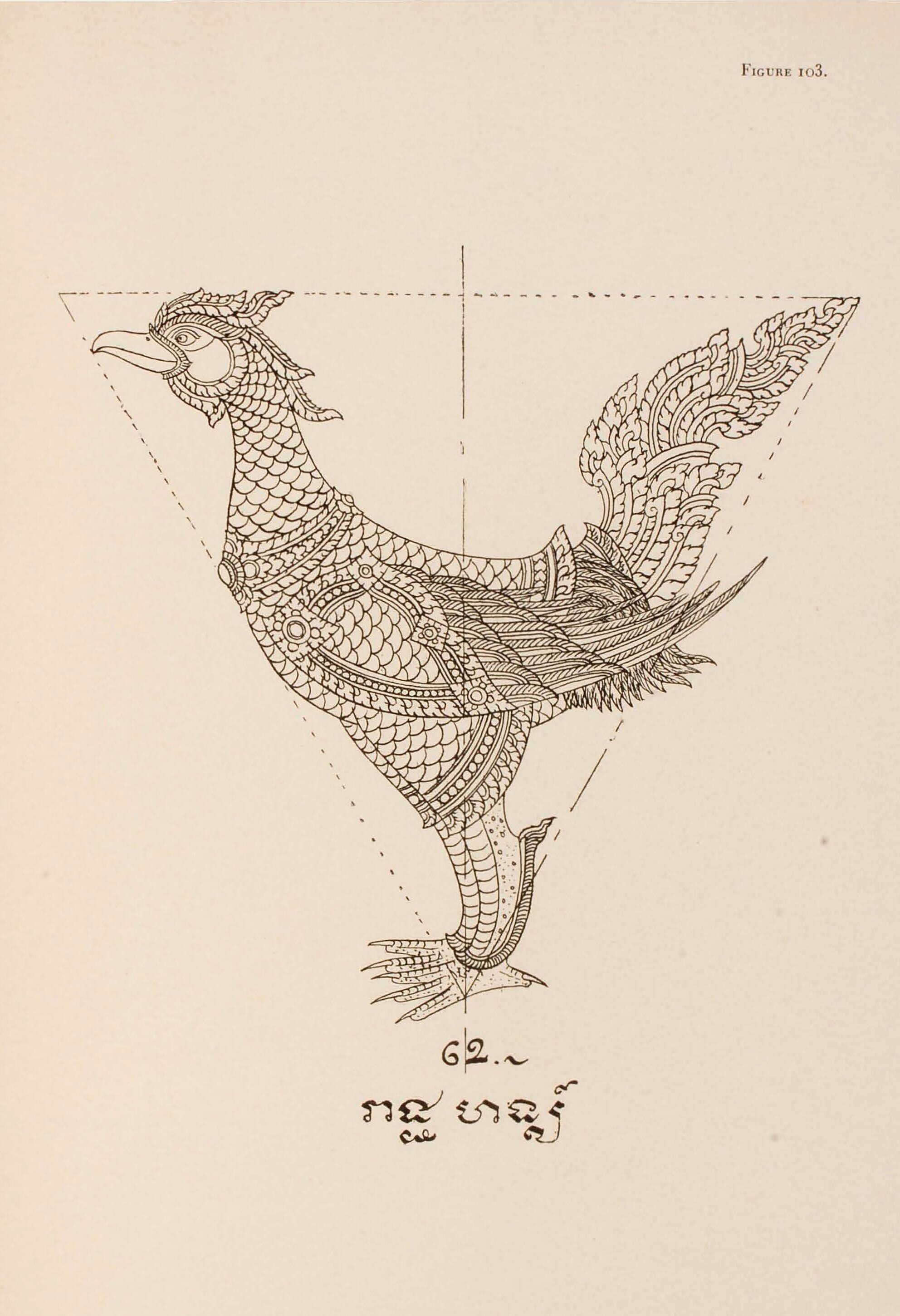

Plate 103 — No. 62. L’oiseau sacré précédent [Hamsa], traité à la moderne.

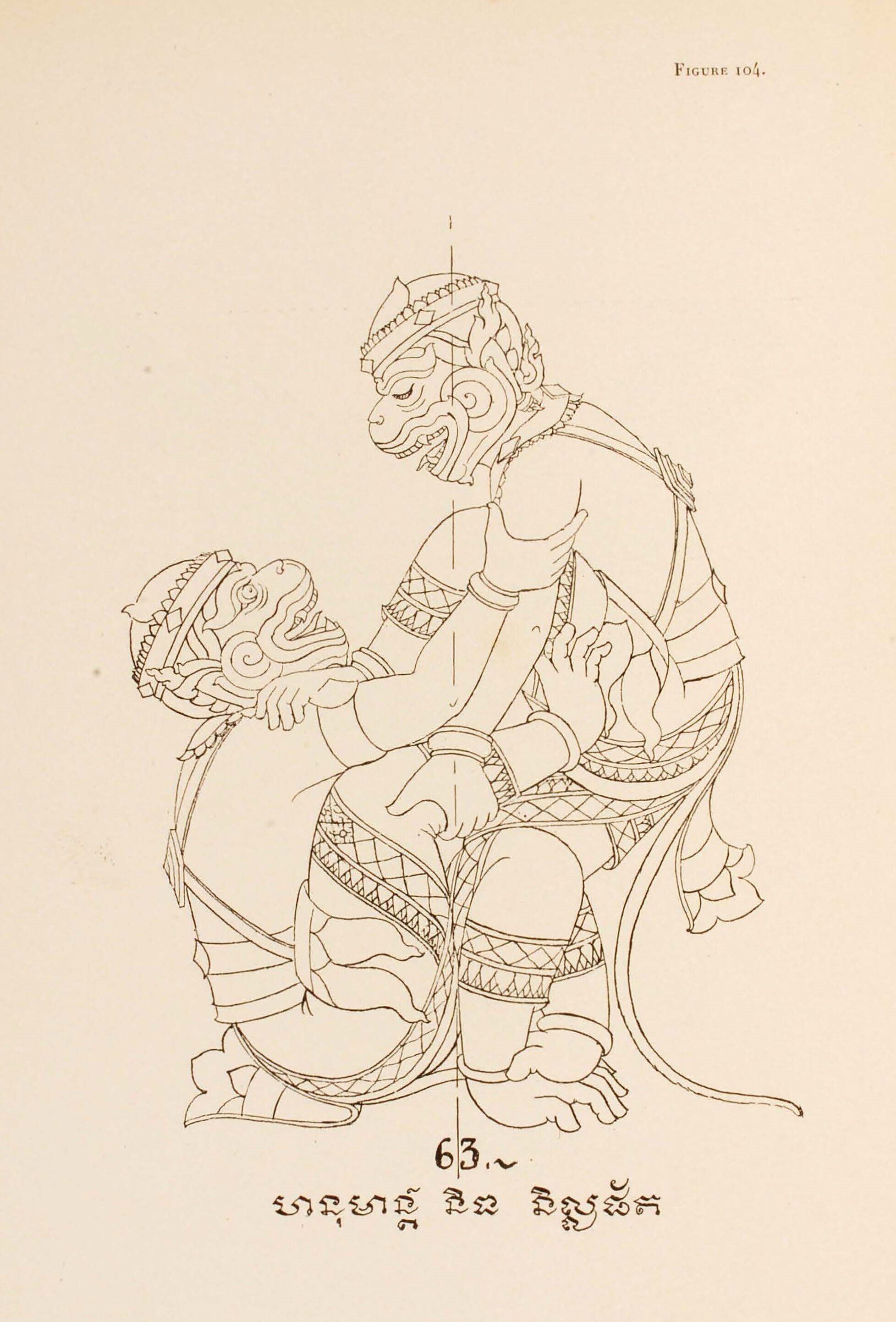

Plate 104 — No. 63. Hanuman et Nilophat, nouvelle scene de lutte, variante de celles que nous avons déja vues.

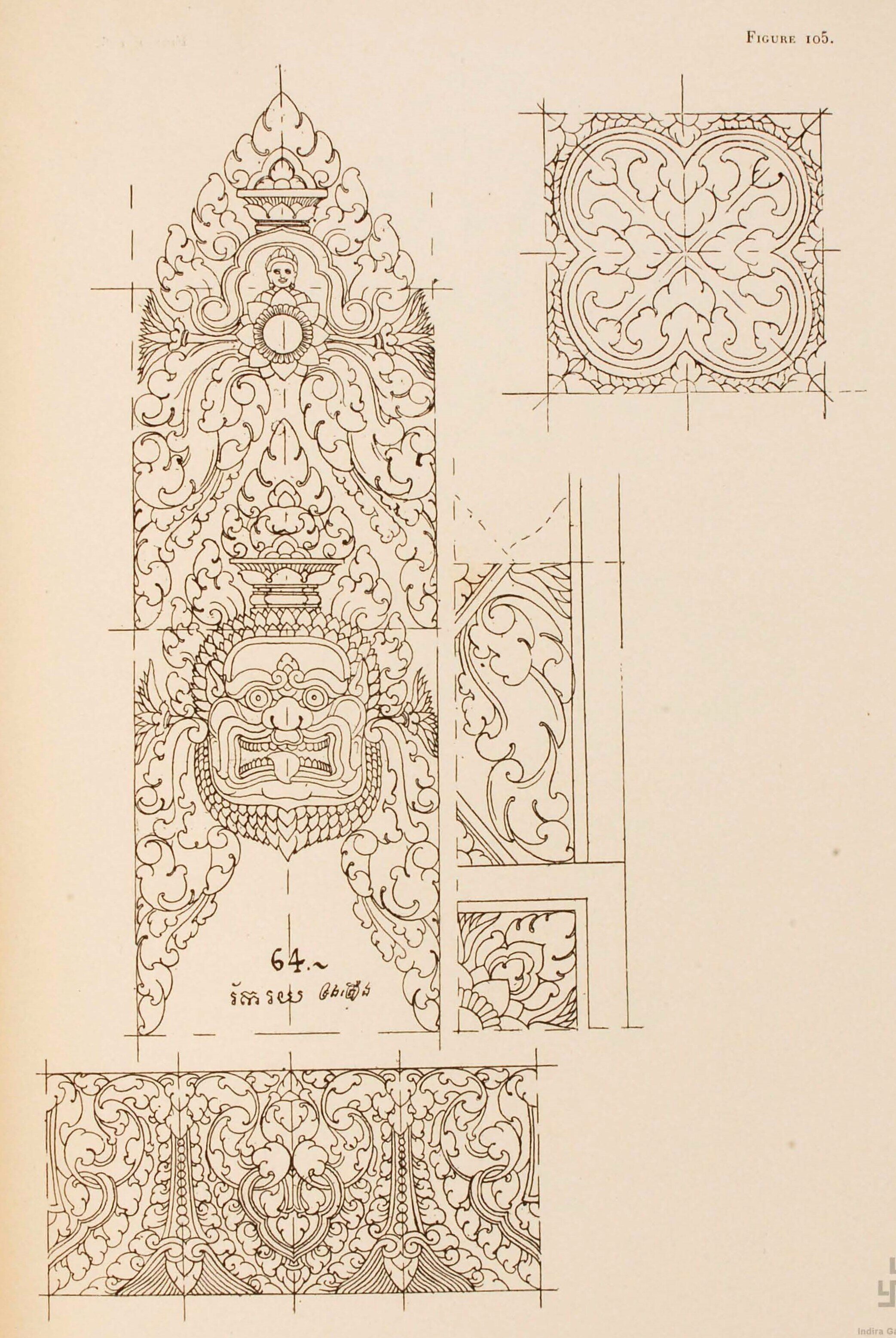

Plate 105 — No. 64. Copie de décors classiques.

Plate 106 — No. 65. Représentation contemporaine de Brahma chevauchant son oie sacrée.

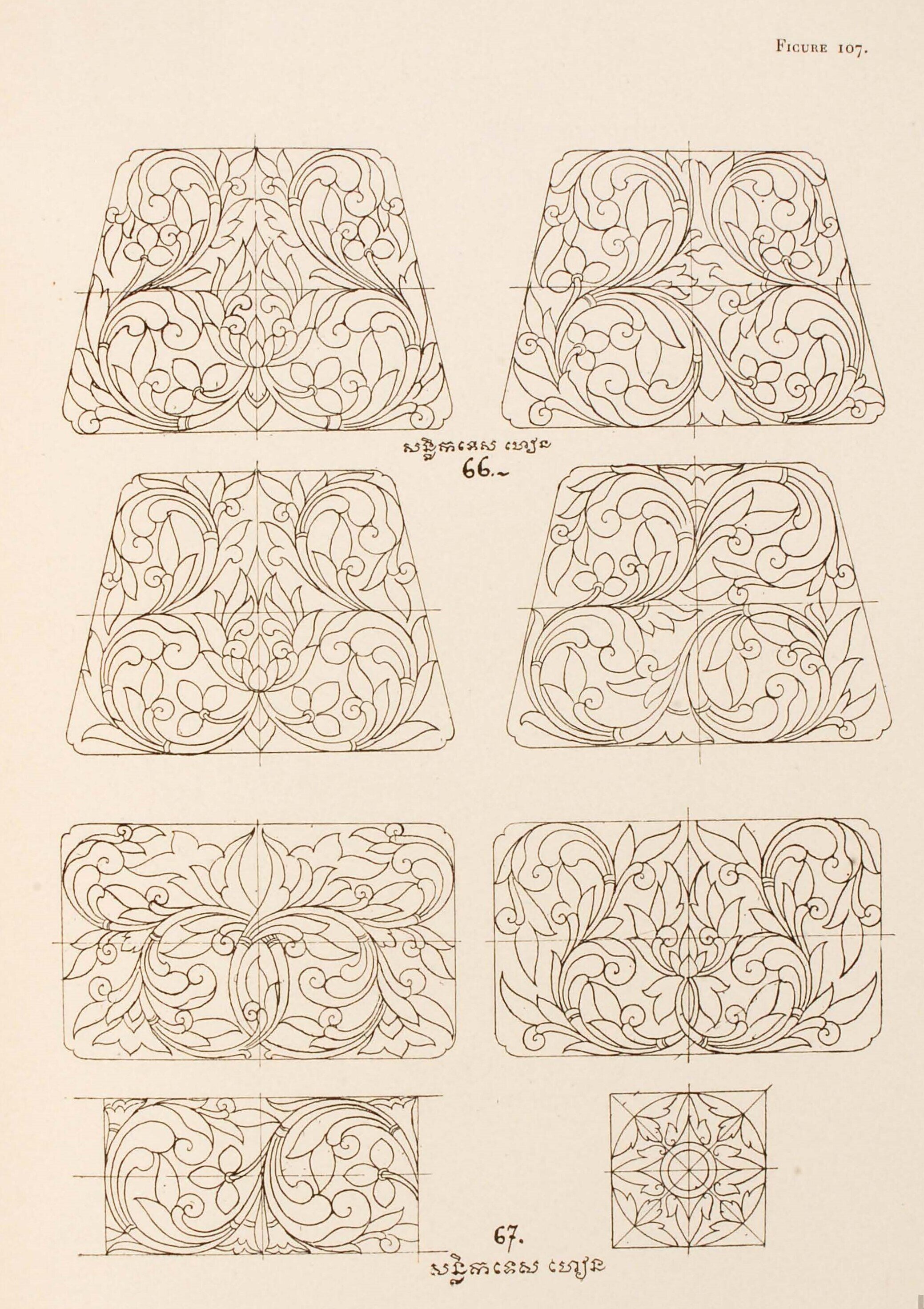

Plate 107 — Nos. 66 – 67. Modeles de sculpture de feuilles décoratives.

Plate 108 — Nos. 68 – 69. Représentation d’un costume royal.

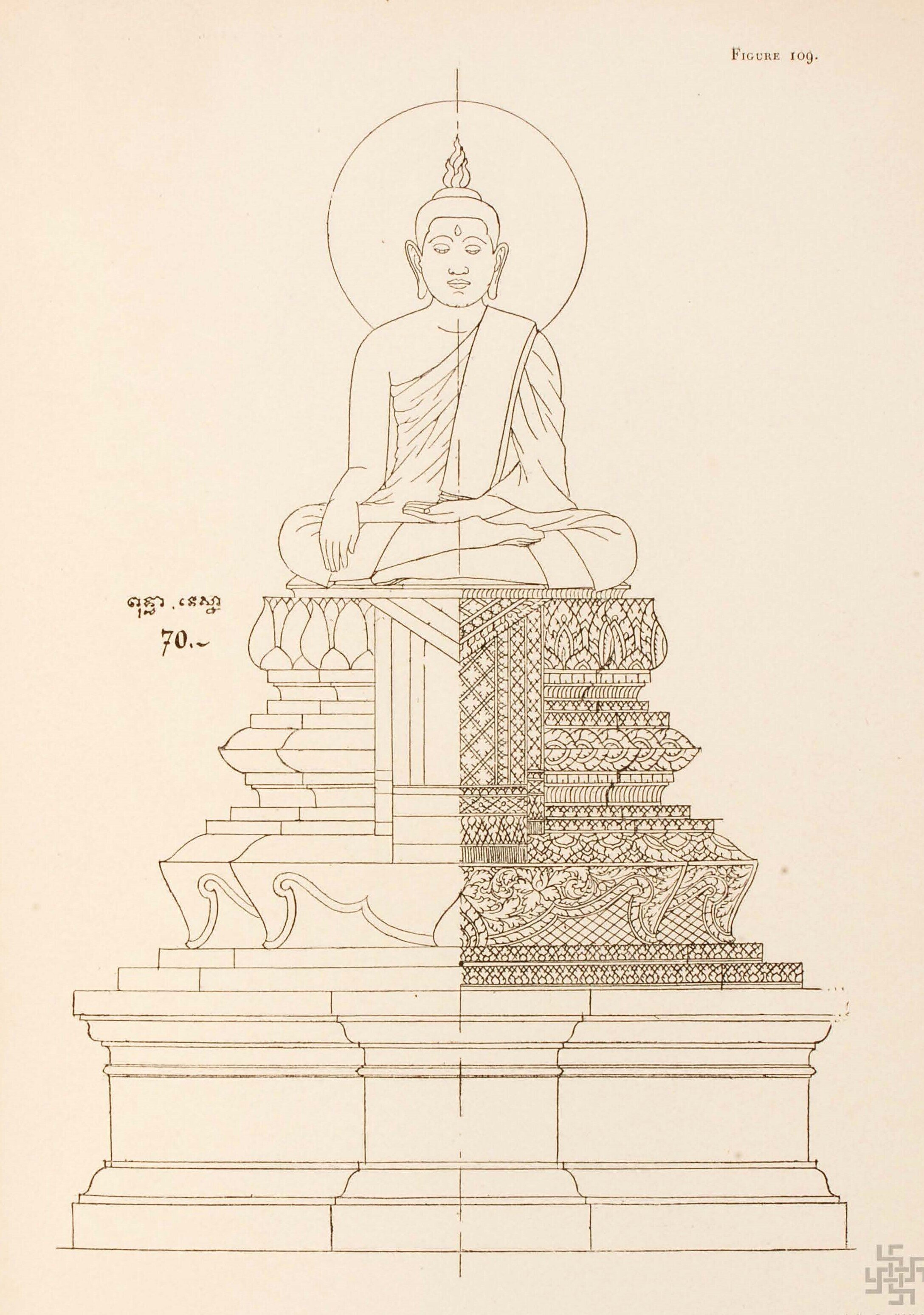

Plate 109 — No. 70. Puth Théa Tesna: Le Buddha attestant la terre.

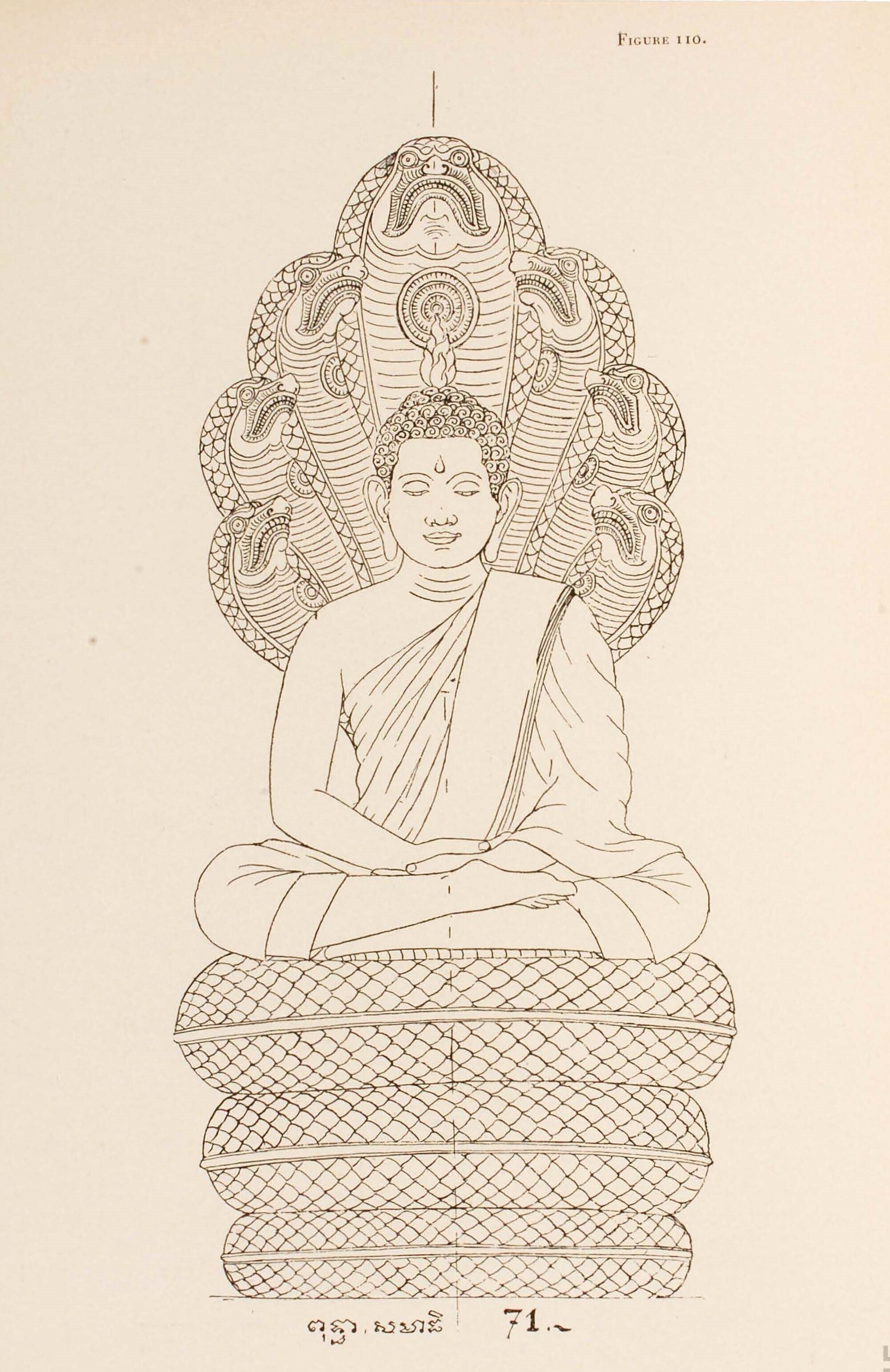

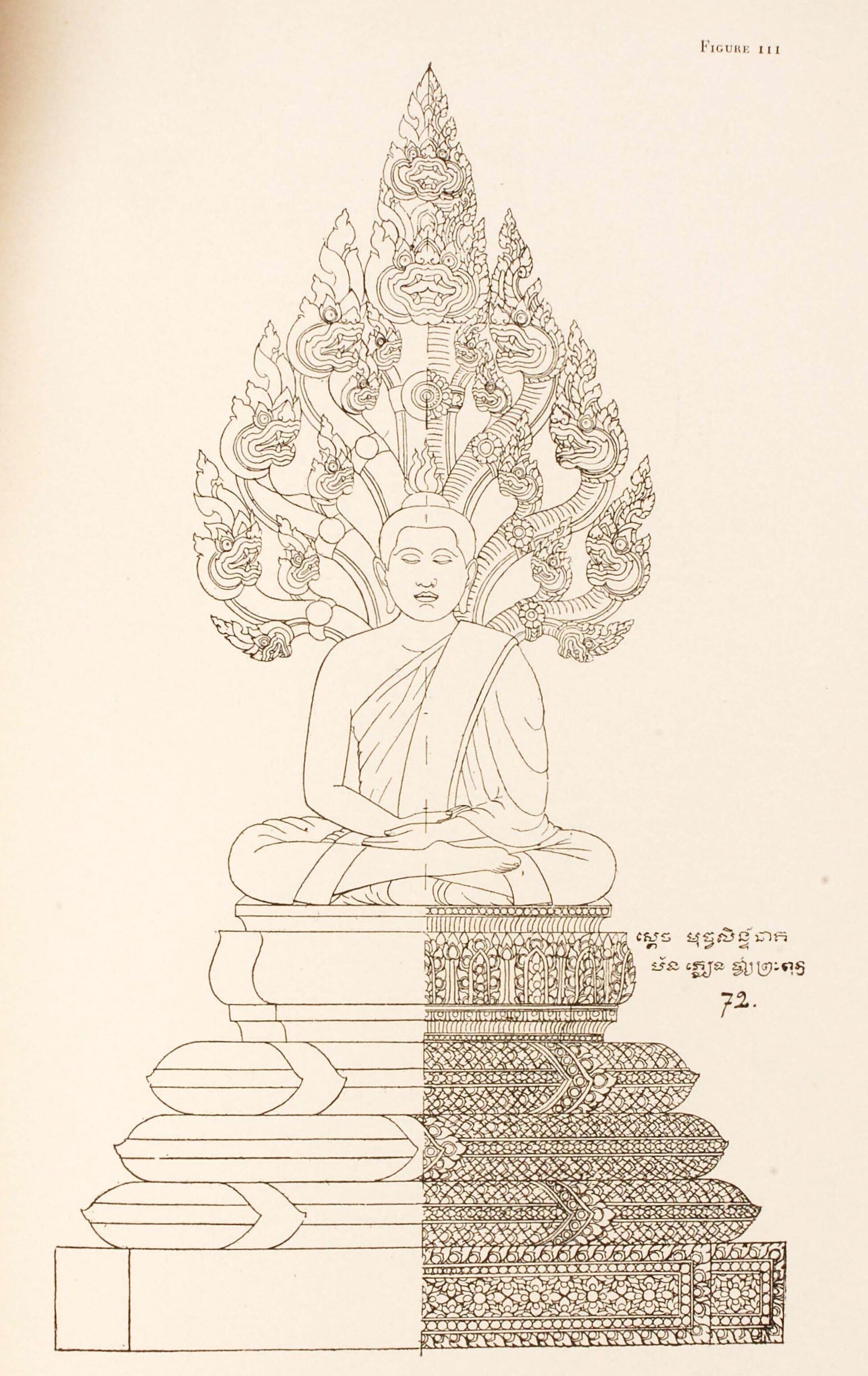

Plate 110 — No. 71. Puth Théa Saméathi: Le Buddha méditant. Le costume est contemporain, mais le Naga d’allure classique. Le comparer pour s’en rendre compte au suivant.

Plate 111 — No. 72. Le roi Muchhalin (Mucalinda) préserve le Buddha de l’orage. Constater la belle transformation du corps lové du serpent en moulures du trône.

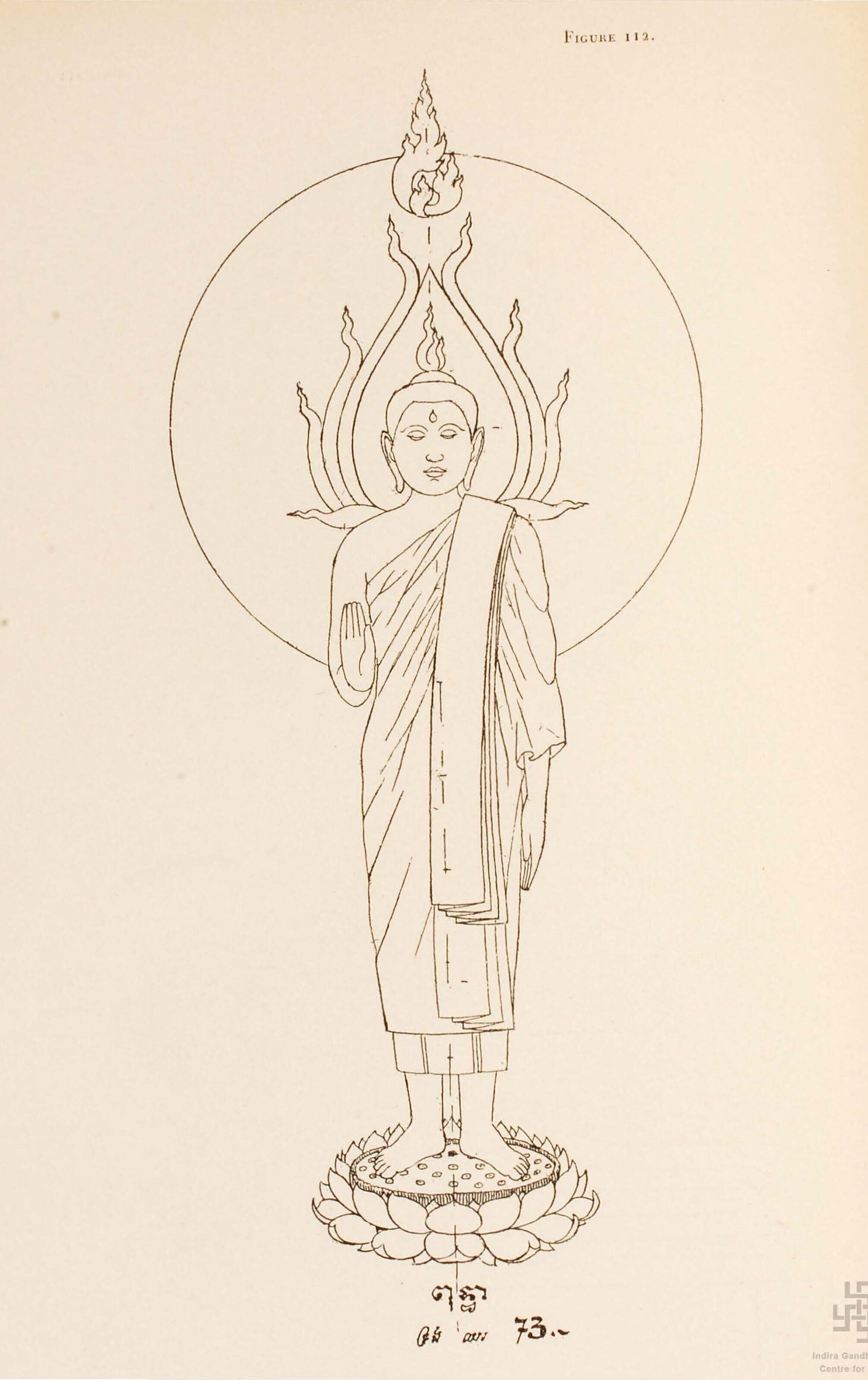

Plate 112 — No. 73. Puth Théa trong chhor, Le Buddha debout fait le geste qui rassure.

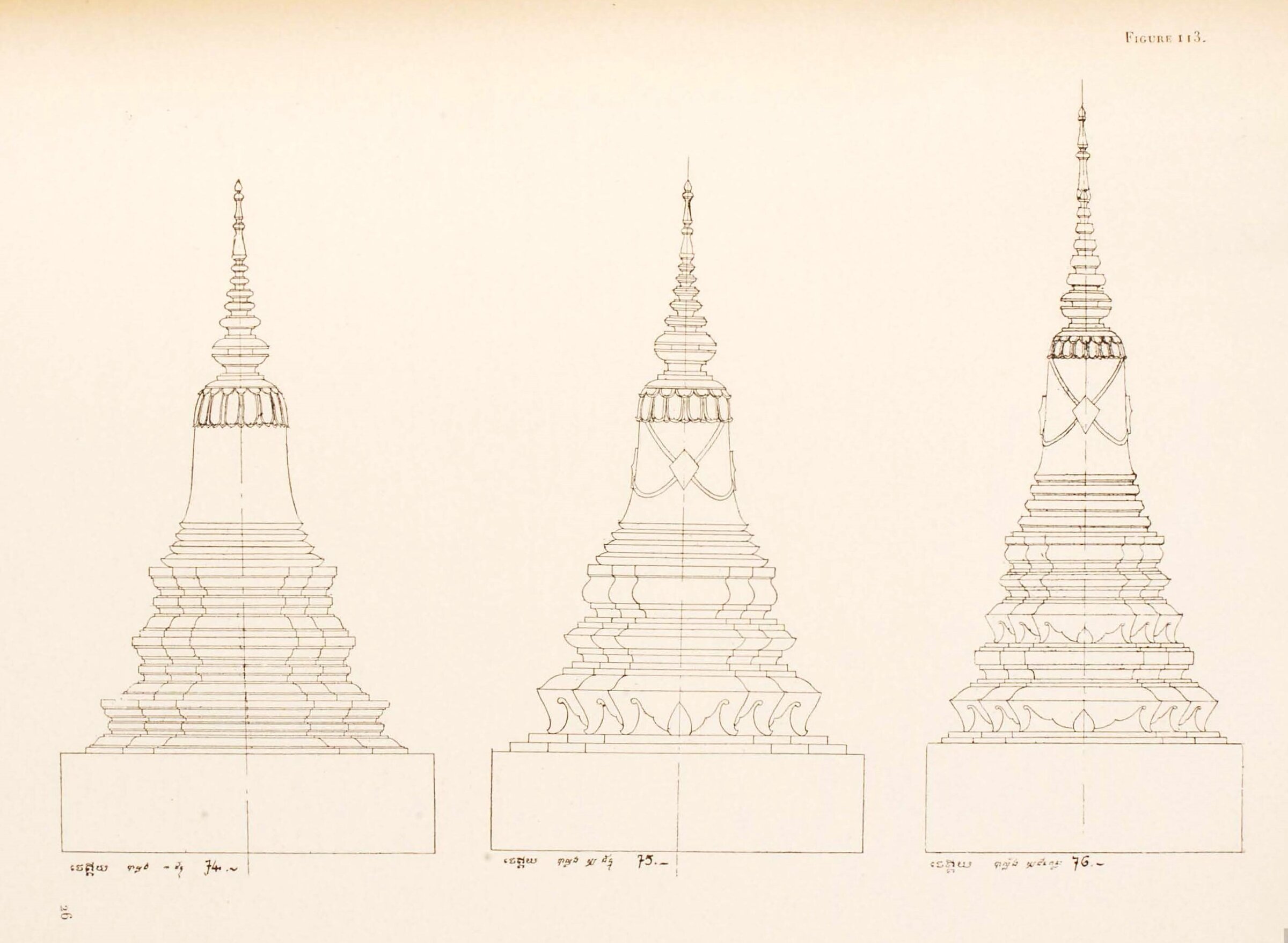

Plate 113 — Nos. 74, 75, 76. Types de chédei (chaytia, stupa) à trois, un et un étage et demi.

Plate 114 — En cul-de-lampe. Sokrip, Hanuman et Ankot: les trois singes légendaires des démêlés de Rama et de Ravana.

Plate 69 — N. 1: Model of a man’s face. — The top figure is inspired by a classic statue head. The conical part of the hairstyle (makuta) has been naively treated in perspective. The head at the bottom points out to us that in contemporary art as in classical art the faces of superior beings are often provided with mustaches. | N. 2: Head of a man wearing the mokoth. This hairstyle derives from the previous one. It is inseparable from the representation of any hero or heroine, god or goddess. These contemporary shapes are combined with the classic earring par excellence: stylization of the lotus button. | Num 3: This is the canon of the human body, eight faces in the body. One wonders why the artist felt the need to dress his example in classic underpants. This proportion does not seem to correspond to that of the past.

Plate 70 — N. 4.5: Representation of lokhon standing and sitting in the sampéah position (lokhon =

actress, dancer). There we see the details of the costume of a prince or god, and a princess or goddess. Sampéah is the great salutation, the anjali of India.

Plate 71 — N. 6. Hanuman. The heroic and warrior monkey, ally of Rama whom he helps to find Sita. He is one of the most popular characters in the Khmer Ramayana.

Plate 72 — N. 8. Samdach Kuveru Reach: Kubera. Pose of anger and defiance. We meet the demonic mask.

Plate 73 — N. 9. After having studied all sufficient details, the student is now invited to deliver a complete scene from the epic. Our three heroes in fig. 114 seek assistance from Prah Ream (Rama) and his brother Prah Lakkhs (Lakshmana). Note the naïve meticulousness of the small plants to which the old sculptors have accustomed us in their bas-reliefs.

Plate 74 — N. 10. Tosaphakr (new model). Ravana, the captor of Sita, king of the Yakshas and Lanka, the “monster with ten heads”. | N. 11 allows us a comparison with the classic Ravana, but doubtful, especially the one on the right.

Plate 75 — N. 12. Series of heads of legendary characters: Entochet, Koberon, Tapanéasaur, Méaron, etc. Each is clearly indicated by a detail of the hairstyle, if not the face.

Plate 76 — N. 13. New scene. Ravana gives audience on his state bed.

Plate 77 — N. 14. Prah Noréai [Preah Noreay] on Kruth (Vishnu on Garuda). Copy of bas-relief executed to enable us to compare the corresponding contemporary composition of the following drawing, N. 17. | N. 15. The Naga: the decorative motif dear to the Khmers for fifteen centuries: the head and tail.

Plate 78 — N. 16. The king of the Vak in a fighting attitude. | N. 17. Vishnu on Garuda.

Plate 79 — N. 18. Half-pediment of a pagoda bearing Prah Entro (Indra) among a floral decoration. | N. 19. Console: the stylized Garuda. | No. 20. Same architectural motif as 18, but showing Vishnu among a decoration of flames. The place, the order, the decorative spirit of this composition come directly from classical monuments.

Plate 80 — N. 21. Half-pediment of a pagoda: priestly fan surrounded by a decoration of flames. | N. 22. Nonkot khnok: end decorative motif (face and profile).

Plate 81 — N. 23. Hanuman and Nélophat: very remarkable composition where Khmer decorative fantasy appears clearly.

Plate 82 — N. 24. The duel of Péali and Sokrip, the two enemy brothers. | N. 25 and 26. Here are two classic decorative motifs copied from the originals. At the top the foliage, at the bottom a composition that contemporary artists call “sugar cane knots”, and fancifully taken for the decoration of an elephant saddle. The elephant being fond of sugar cane… there is obviously only one step to make to establish the connection. But we must be seriously wary of Khmer rapprochements.

Plate 83 — N. 27. Prah Vésandar meditating in asceticism, a tiger skin as a scarf. | N. 28. Copy of a wall decoration at Angkor Wat.

Plate 84 — N. 29. Rama carried by Hanuman, shooting from the bow during his furious fight against Ravana. On the left, a warrior monkey.

Plate 85 — N. 30, 31, 32. Tevoda, flying Tevothida: the graceful male and female spirits of the air, the Khmer angel. Since the 9th century, this pose on the knee and raised foot has been that of characters circulating in the air, leaving the ground.

Plate 86 — N. 33 – 36. Copies of bracelets, saltire plates and belts of classical art preserved at A. Sarraut Museum. 36 is the flat application of pattern 35, executed in relief.

Plate 87 — N. 37 and 38. Kenar: flying nymphs and genies, mixture of classical sculpture and contemporary details.

Plate 88 — N. 39. “Charék” box in the shape of a terminal. Composition on a given theme to be executed in stamped and embossed silver. Mixture of classic-looking characters with a contemporary décor.

Plate 89 — N. 40. Kenar. A whole family of these winged figures that we saw in their almost classic form in figures 33 to 36, and who are here dressed in their clearly contemporary costume. The actress who plays this role in a ballet keeps this costume on.

Plate 90 — N. 41−42−43. The three monkeys whose head details are studied in fig 114 are here represented in full in combat poses.

Plate 91– N. 44 and 48. Details of the decoration of the ornamental plates on the princely baldric goldwork. | No. 45. Box decorated with the representation of Sovanméchéa | N. 46 and 47, “méchéan” box; 49, “Tep Pramam” box. These popular boxes, made of embossed silver and gold, are used to store tobacco. We see represented various hybrid heroes of Khmer legend.

Plate 92 — N. 50. The Garuda copied on the Angkorian bas-relief is as it is depicted in the current illuminations.

Plate 93 — N. 51. Tosaphakr and all its attributes.

Plate 94 — N. 52. Copy of classic false door panel sculpture.

Plate 95 — N. 53. Large fight scene where Rama finally triumphs over Ravana.

Plate 96 — N. 54. Lion. Design inspired by the classic round boss. Fight of Hanuman and Mechan, variant of the duel scenes in figs. 81, 82.

Plate 97 — N. 56. The modern lion.

Plate 98 — N. 57. Prah Eisaur: Shiva. This group is inspired by a statue of Shiva and his Shakti from the classical period kept at the Albert Sarraut Museum. The artist limited himself to dressing these divinities in modern fashion.

Plate 99 — N. 58. Royal bed end decoration called “mondap”. Flaming Naga tail stylization.

Plate 100 — N. 59. Péali and the buffalo Topi. The stylization of the animal does not succeed in removing from it a certain extremely well observed naturalistic aspect.

Plate 101 — N. 60. Prah Pisnukar, the divine architect, great patron of craftsmen Certain decorations on the base could be juxtaposed with classical motifs,

Plate 102 — N. 61. Prah Prom on Hangs (Brahma on Hamsa). Another copy of à bas-relief from Angkor Wat. See the same scene fig 106.

Plate 103 — N. 62. The previous sacred bird [Hamsa], treated in the modern way.

Plate 104 — N. 63. Hanuman and Nilophat, new wrestling scene, variation on those we have already seen.

Plate 105 — N. 64. Copy of classic decorations.

Plate 106 — N. 65. Contemporary representation of Brahma riding his sacred goose.

Plate 107 — Ns. 66 – 67. Decorative leaf sculpture models.

Plate 108 — Ns. 68 – 69. Representation of a royal costume.

Plate 109 — N. 70. Puth Théa Tesna: The Buddha attesting to the earth. [Bhumisparsha mudra]

Plate 110 — N. 71. Puth Théa Saméathi: The meditating Buddha [Dhyani mudra]. The costume is contemporary, yet the Naga looks classic. Compare it to the next one.

Plate 111 — N. 72. King Muchhalin (Mucalinda) preserves the Buddha from the storm. Note the beautiful transformation of the coiled body of the serpent into the moldings of the throne. [Mucalinda mudra]

Plate 112 — N. 73. Puth Théa trong chhor, The standing Buddha makes the reassuring gesture. [Abhaya mudra]

Plate 113 — N. 74, 75, 76. Types of chedei (chaytia, stupa) with three, one and one and a half stories.

Plate 114 — In cul-de-lampe. Sokrip, Hanuman and Ankot: the three legendary monkeys from the quarrels of Rama and Ravana.