ingot

eng ingot | fr lingot

An ingot is a mass of metal that has been cast into a size and shape (bar, plate, sheet) to be stored, exchanged, or worked on into a semi-finished or finished product.

by George Groslier

George Groslier's encyclopaedia-like sum on the Ancient Khmer civilization, "d'après les textes et les monuments depuis les premiers siècles de notre ère".

Based on “travels and missions in Cambodia from 1909 to 1914 and from 1917 to 1920”, this ambitious work was attempted as “an ethnographic portrait of the Khmer people”, past and present, but the author downsized the scope of his research and focussed on the Ancient Khmer civilization. Later on, he published an additional volume, Nouvelles recherches sur les Cambodgiens.

Among the sources used by the author, we shall note the prevalence of Chinese chroniclers, in particular Tchou-Ta-Kouan (Zhou Daguan). When the book was published, many Khmer inscriptions had yet to be discovered and deciphered. It must also be stressed that with this essay G. Groslier was a real pioneer in material culture research.

Part II

with 200 photographs, 43 plates and 179 drawings by the author.

There are countless important notations drawn from the author’s field work at Angkor, in various Khmer temples, and around modern pagodas and palaces. From the fact that he collected “small residues of black or red resin plated with gold” from small gaps between stones at Angkor Wat, to the hypothesis on the hauling system used for large stone blocks at Prasat Beng Maelea or Takeo of Angkor, to the elaborate floorplans of Udong (around 1860) and Phnom Penh (in 1913) Royal Palaces, reproduced here below:

Au Cambodge, l’usage des monnaies né paraît pas remonter à une époque bien lointaine ou du moins, jusqu’au xveme siècle, les documents en notre possession n’en soufflent mot. Le chapitre précédent a précisé qu’au xiiie siècle la monnaie était inconnue et que les paiements avaient lieu en nature ou que les petites affaires s’elfectuaient 2par voie d’échange. L’argent importé de Chine ainsi que nous l’a dit Tchou Ta Kouan, l’était probablement avec des poids bien définis, surtout que « dans les grandes transactions on se servait d’or et d’argent ». Ce poids courant que nous connaissons et qui en Chine n’a jamais varié est le taël, en cambodgien dâmleng. Cette barre ou lingot fut certainement le mode de paiement régulier qui, usité du moins à la fin de l’époque classique, n’a pas disparu complètement. Elle pèse exactement, en poids du pays : 1 dâmleng 2 chi, soit 382gr50. Elle est en argent théoriquement pur, coulée en Chine et vaut de 14 à 15 piastres, on l’appelle nèn. La barre d’or qui a complètement disparu et qui pesait le même poids, valait 16 nèn et se nommait meas chdor. Elle circulait sous forme d’une épaisse plaque carrée, revêtue de caraclères chinois et a été remplacée par un petit carnet de feuilles d’or laminées pesant 1 taël. Enfin, on conserve encore au Trésor du Palais deux lingots d’argent chinois, de forme conoïde qui eurent cours jadis et valaient 10 nèn et pèsent respectivement 3kgr820 : phduoeng. […] Ce n’est qu’un siècle et demi plus tard, en 1595, que nous apprenons avec certitude et des détails du plus haut intérêt que le Roi du Cambodge, Sotha Ier, faisait battre monnaie. Depuis cette époque, l’usage de la monnaie d’argent et de bronze est permanent. Certaines pièces étrangères annamites, siamoises, peut-être espagnoles et portugaises, ont encours dans le pays et leur équivalence en monnaie indigène jusqu’à la frappé d’Ang Duong bien connue des numismates et qui fut la dernière exécutée par les Cambodgiens avant l’établissement du Protectorat français.

Les spécimens de monnaie que l’on retrouve sont de trois sortes : en argent, en bronze et en bronze argenté. Le bronze est un alliage où le cuivre rouge domine et où rentrait une parcelle d’argent. Deux types ; face et pile avec caractères face seulement, pile nue et quelquefois un caractère sur la face. Sauf la pièce dite Prak bat datée de 1846 et qui fut frappée avec un coin à balancier euiopéen qui existe toujours au Palais royal, toutes les autres monnaies que j’ai trouvées dans le pays ont été coulées en séries par un procédé qui, analogue à celui de la fonte des sapeques annamites, a dû probablement s’en inspirer. Les sapèques en ligature avaient en effet cours au Cambodge au xviiieme siècle au plus tard puisque les pièces cambodgiennes frappées à celte époque ont des valeurs correspondantes à des nombres bien déterminés de sapèques. […]

[In Cambodia, the use of currencies does not seem to date back to a very distant time or at least, until the 15th century, the documents in our possession do not mention it. The previous chapter specified that in the 13th century currency was unknown and that payments were made in kind or that small transactions were carried out by way of exchange. The money imported from China, as Tchou Ta Kouan [Zhou Daguan] told us, was probably with well-defined weights, especially since “in large transactions gold and silver were used”. This current weight that we know and which has never varied in China is the tael, in Cambodian dâmleng. This bar or ingot was certainly the regular method of payment which, used at least at the end of the classical period, has not completely disappeared. It weighs exactly, in the country’s weight: 1 dâmleng 2 chi, or 382gr50. It is theoretically pure silver, cast in China and worth 14 to 15 piastres, it is called nèn. The gold bar which has completely disappeared and which weighed the same weight, was worth 16 nèn and was called meas chdor. It circulated in the form of a thick square plate, covered with Chinese characters and was replaced by a small book of rolled gold leaves weighing 1 tael. Finally, two Chinese silver ingots, conoid in shape, which were once current and worth 10 nèn and weigh 3kgr820 respectively: phduoeng, are still kept in the Palace Treasury. […] It was only a century and a half later, in 1595, that we learned with certainty and details of the greatest interest that the King of Cambodia, Sotha I [1], had money minted. Since that time, the use of silver and bronze coins has been permanent. Some foreign coins from Annamese, Siamese, perhaps Spanish and Portuguese, were in circulation in the country and their equivalent in indigenous currency until the Ang Duong minting well known to numismatists and which was the last executed by the Cambodians before the establishment of the French Protectorate.

The specimens of coins that we find are of three types: silver, bronze and silvered bronze. Bronze is an alloy where red copper dominates and where a piece of silver entered. Two types; head and tail with characters head only, bare tail and sometimes a character on the face. Except for the coin called Prak bat dated 1846 and which was minted with a European pendulum die which still exists at the Royal Palace, all the other coins that I found in the country were cast in series by a process which, similar to that of the casting of Annamese sapeques, must probably have been inspired by it. Ligature sapèques were in fact in circulation in Cambodia in the 18th century at the latest since the Cambodian coins minted at that time have valuescorresponding to very specific numbers of sapèques. […]

[1] Mak Phoeun, Histoire du Cambodge, p 245: “Selon les chroniques royales du Cambodge, c’est le roi usurpateur Sri Jeṭṭhā (Stec Kan), qui régna vers les premières décennies du XVI siècle, qui le premier avait fait battre monnaie et avait mis en circulation des pièces en or et en argent portant une image de nāga, pièces appelées slin.” [According to the royal chronicles of Cambodia, it was the usurper king Sri Jeṭṭhā (Stec Kan), who reigned around the first decades of the 16th century, who first minted coins and put into circulation gold and silver coins bearing an image of a nāga, coins called slin. [ថ្លឹង or ស្លឹង in Middle Khmer according to Philip Jenner]

Nous arrivons ainsi, en suivant, autant qu’il est possible, l’ordre chronologique à la dernière monnaie de provenance cambodgienne, appelée Prak bat, la seule qui fut frappée, sous le règne d’Ang Duong (avènement 1847, mort en 1859). Il semble qu’il y eut plusieurs flancs par modèle. Les frappes sont très belles et d’un fort relief. Quatre modèles A, B, C, D (fig. 10), argent.

A. Face. — Un temple couvert de tuiles à deux toitures superposées et appentis; trois tours se terminant par un double trident. Tour centrale à cinq étages et fronton évidé. Dans le portique, les deux mots superposés: Krong Kampuchéa (Cambodge). Dans les quatre entrecolonnements de la vérandab : Anthâpât (nom de capitale). | Pile. — L’oiseau Hamsa, passant de droite à gauche et déterminant trois quartiers. En haut: Prah Sakkrach 2890 (ère de Buddba = 1846 A. D.); chhnam Momé nuphsakkh, année de la chèvre, 9e de la décade ; et la date : 3 eme jour de la lune croissante du 4eme mois. En bas à gauche : Mâhasakkhrach 1769 (grande Ere= 1846 A. D.). En bas a droite : Cholsakkhrach 1209 (ère cholsakkkrach= 1846 A. D.)

B. Plus petit que le précédent mais plus épais, d’un poids théoriquement égal et de même valeur.

Face. — Le temple n’a qu’une toiture simple. Les tours sont à trois étages. Le mot anthàpât au lieu d’être en 4 groupes de lettres est divisé en deux, de chaque côté du portique, et les mots Krong Kampuchea, au lieu d’être disposés sur deux lignes, le sont sur trois. Pile. — Semblable à A.C. Les dates seules figurent, mais sont inversées, dans les deux quartiers supérieurs, et la pagode n’est qu’à une seule tour.

D. Aucun caractère ni date, et comme sur le précédent modèle, le temple n’est qu’à une seule tour d’un étage. Depuis le règne de Norodom, cette monnaie n’a plus cours. A est encore connu, B et D ont disparu. Bien qu’il soit convenu de penser que cette pièce n’a été frappée qu’en argent, je n’en ai pas moins examiné un exemplaire coulé en bronze un peu plus petit que le type D, épais, né portant que l’oiseau Hamsa d’un fort relief, passant de droite à gauche, tenant un ornement ou fleur dans le bec et surmonté de la date: 3e jour de la lune croissante du 4eme mois,

disposée en caractères simplifiés, semblable à celle du type C. Rien sur la pile.[..] On m’a parlé plusieurs fois, sans que jamais mes recherches pussent aboutir, d’une grande pièce en argent que les vieux Cambodgiens se souviennent d’avoir vue. Elle aurait circulé une cinquantaine d’années avant la frappé du Prak bat, ce qui nous reporterait vers 1790. C’est une pièce dite Prak sema d’un diamètre un peu plus grand que le Prak bat giand modèle, dont le poids était de 10 chi ou 1 taël et la valeur de 10 ligatures. Sur une face était figuré un sema, borne servant à limiter les terrains sacrés, de chaque côté s’enroulaient des ornements. Des caractères figuraient sous le sema. Au verso, s’étalait une sorte de soleil en relief entouré de rayons grands et petits alternés. [p 30 – 37]

We thus arrive, following, as far as possible, the chronological order at the last coin of Cambodian origin, called Prak bat, the only one that was minted under the reign of Ang Duong (accession 1847, death in 1859). It seems that there were several sides per model. The strikes are very beautiful and of a strong relief. Four models A, B, C, D (fig. 10), silver.

A. Heads. — A temple covered with tiles with two superimposed roofs and lean-tos; three towers ending in a double trident. Central tower with five floors and hollowed-out pediment. In the portico, the two superimposed words: Krong Kampuchea (Cambodia). In the four intercolumns of the veranda: Anthâpât (name of a capital city). | Tails. — The Hamsa bird, passing from right to left and determining three quarters. Top: Prah Sakkrach 2890 (Buddba era = 1846 A.D.); chhnam Momé nuphsakkh, year of the goat, 9th of the decade; and the date: 3rd day of the waxing moon of the 4th month. Bottom left: Mâhasakkhrach 1769 (great Era = 1846 A.D.). Bottom right: Cholsakkhrach 1209 (cholsakkkrach era = 1846 A.D.)

B. Smaller than the previous one but thicker, of theoretically equal weight and value. Heads. — The temple has only a simple roof. The towers are three-storeyed. The word anthàpât instead of being in 4 groups of letters is divided into two, on each side of the portico, and the words Krong Kampuchea, instead of being arranged on two lines, are on three. Tails. — Similar to A.

C. Only the dates appear, but are reversed, in the two upper quarters, and the pagoda is only one tower away.

D. No characters or dates, and as on the previous model, the temple is only one tower of one storey. Since the reign of Norodom, this coin has not been in circulation. A is still known, B and D have disappeared. Although it is agreed to think that this coin was issued only in silver, I have nevertheless examined a copy cast in bronze a little smaller than type D, thick, bearing only the Hamsa bird in high relief, passing from right to left, holding an ornament or flower in its beak and surmounted by the date: 3rd day of the waxing moon of the 4th month, arranged in simplified characters, similar to that of type C. Nothing on the tails.

[..] I have been told several times, without my research ever being able to come to anything, about a large silver coin that old Cambodians remember having seen. It is said to have circulated about fifty years before the Prak bat was minted, which would take us back to around 1790. It is a coin called Prak sema with a diameter a little larger than the Prak bat giand model, whose weight was 10 chi or 1 tael and the value of 10 ligatures. On one side was a sema, a boundary stone used to delimit sacred grounds, on each side were ornaments. Characters appeared under the sema. On the back, there was a sort of sun in relief surrounded by alternating large and small rays. [p 30 – 37]

There are various notations on the use of bronze in Khmer statuary, currency minting, tools, kitchen ware, weapons, decorative elements, with the identification of a typical trait: sculptors used the same motives, tools, and techniques when they were working either on stone or bronze. Excerpts:

[1] At the time of writing, the author, as all scholars and researchers of the time, was unaware that the word used by Zhou Daguan, 塔 ta, meant “tower” but also “pagoda” or “stupa. What he really wrote was: “In the pagodas the Buddhas are all different in appearance and all cast in bronze.” [Zhou Daguan, A Record of Cambodia, Its Land and Its People, chap. 5, transl. by Peter Harris]

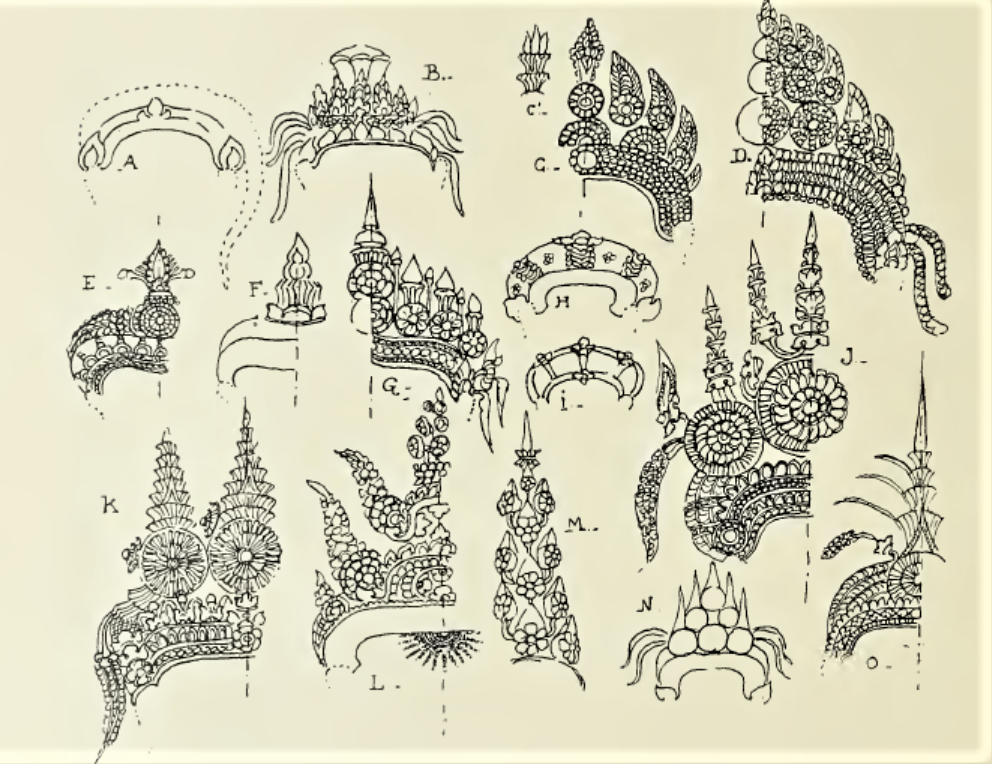

Various Women’s Head Ornaments (drawings by George Groslier)

Tags: ethnography, pre-Angkorean, Khmer Empire, Khmer civilization, sculpture, architecture, material culture, archaeology, Khmer arts, money, bronze, coins

George Groslier [kh ហ្សក ហ្រ្គូសលីយេ, jp ヂョルヂュ・グロスリエ] (4 Feb. 1887, Phnom Penh — 16 June 1945, Phnom Penh), the first child with French citizenship born in modern Cambodia, was an artist, novelist, historian, archaeologist, ethnologist, architect, photographer, and the founder and curator of the National Museum of Cambodia in 1917, as well as the Ecole des arts cambodgiens (School of Cambodian Arts).

While organizing the School of Cambodian Arts (nowadays the Royal University of Fine Arts), Groslier has extensively portrayed and studied the country, its people and its traditions, in his writings, paintings and erudite communications. He founded Phnom Penh Albert Sarraut Museum in 1919, later to become the Cambodia National Museum [Groslier’s wife, Suzanne Poujade (1893−1970), was a niece of Albert Sarraut, former Governor-General of Indochina and then French Minister of the Colonies and future Prime Minister]. The interconnection between the Museum and the School did not survive his death, as the Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient took over the Museum in 1945 [see Gabrielle Abbé, Le développement des arts au Cambodge a l’époque coloniale: George Groslier et l’Ecole des arts cambodgiens (1917−1945”, Udaya 12, 2014: 7 – 39]

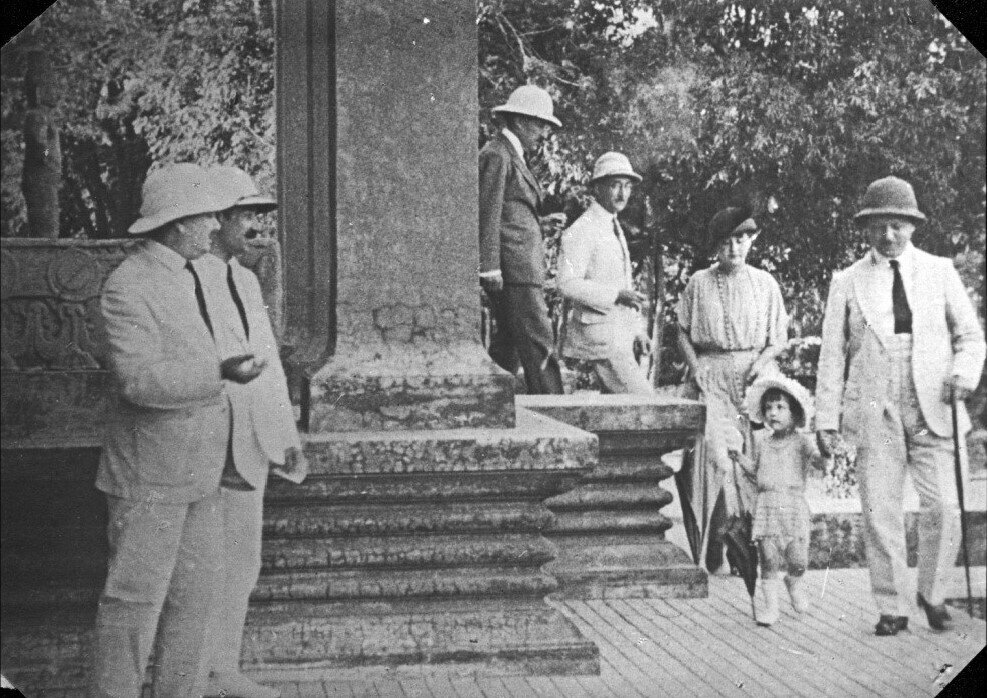

1) Suzanne Poujade and two of the Grosliers’ three children in the 1920s (EFEO). 2) George Groslier with daughter Nicole and Suzanne Poujade, far right, arrive at the Phnom Penh Museum for the 1922 visit of Maréchal Lyautey. Standing on the left side, André Silice and Jean Stoeckel, Groslier’s collaborators [photo courtesy of Kent Davis].

1) Suzanne Poujade and two of the Grosliers’ three children in the 1920s (EFEO). 2) George Groslier with daughter Nicole and Suzanne Poujade, far right, arrive at the Phnom Penh Museum for the 1922 visit of Maréchal Lyautey. Standing on the left side, André Silice and Jean Stoeckel, Groslier’s collaborators [photo courtesy of Kent Davis].

1) Suzanne Poujade and two of the Grosliers’ three children in the 1920s (EFEO). 2) George Groslier with daughter Nicole and Suzanne Poujade, far right, arrive at the Phnom Penh Museum for the 1922 visit of Maréchal Lyautey. Standing on the left side, André Silice and Jean Stoeckel, Groslier’s collaborators [photo courtesy of Kent Davis].

George Groslier was detained and tortured by the Japanese forces when Japan, a former ally of Petain’s French government, occupied vast swaths of South East Asia. Le Journal de Saïgon (7 Dec. 1945) reported six months after his death: “Le 9 mars 1945, Georges Groslier était hospitalisé ; rétabli, il habite le camp où il rédige pour lui un journal de l’occupation japonaise. Le 1er juin, une rechute l’oblige à rentrer à nouveau à l’hôpital. Le 16 juin, il est arrêté par les Japonais, sorti de son lit et conduit à la Gendarmerie japonaise. Interrogé, torturé, il meurt à la suite du supplice de l’eau. Incinéré, ses cendres sont remises le 22 juin à sa famille. Déposé à la chapelle de l’Évêché, l’urne funéraire en sort le 25 juin pour être transportée au cimetière. Les dirigeants du camp français obtiennent des autorités japonaises que l’urne traverse le camp français et que 20 Français soient autorisés à sortir du camp pour l’accompagner au cimetière. Le matin du 25 juin, à 8 heures, le petit cortège traverse le camp, tous les Français sont rangés sur son parcours : dernier hommage à une noble victime.” [“On March 9, 1945, Georges Groslier was hospitalized; after he recovered, he lived in the camp where he wrote a diary of the Japanese occupation. On June 1, a relapse forced him to return to the hospital. On June 16, he was arrested by the Japanese, taken from his bed, and taken to the Japanese military police. Interrogated and tortured, he died following the water torture. Cremated, his ashes were given to his family on June 22. Placed in the chapel of the Bishopric, the funeral urn left on June 25 to be transported to the cemetery. The leaders of the French camp obtained from the Japanese authorities that the urn cross the French camp and that 20 French people be authorized to leave the camp to accompany it to the cemetery. On the morning of June 25, at 8 a.m., the small procession crossed the camp, all the French people lined up along its route: a final tribute to a noble victim.” Later, George Groslier’s ashes were transferred to France by his family, and have been interred in the family crypt in the 2020s.

With Suzanne Poujade, he had three children, Nicole, Gilbert and Bernard-Philippe, the latter following his father’s steps and becoming an eminent researcher in Cambodian archaeology and history.

George Groslier’ scientific and artistic contribution to Khmer archaeology and cultural history is celebrated, as well as his committment to protect the Cambodian cultural heritage — for instance when he successfully prevented André Malraux to take abroad the spoils of his plundering of Banteay Srei temple. Researcher Kent Davis has described him as ‘Le Khmerophile’ par excellence in the most complete biographical work about him, and has edited the English translation of five of Groslier’s major contributions (all published by DatASIA Press). Recent works by young researchers, however, have claimed that his official responsibilities somehow submitted him to the French colonial system, and his often pessimistic outlook of the “decline of the Cambodian arts” played along with the colonial system.

Nevertheless, his important photographic work on the rehearsals of the Royal Ballet dancers in 1927 has been restored and presented to the public in 2019. His statue still remains pre-eminent at the National Museum, and the debate around the validity of giving back the name of Rue Groslier (Groslier Street) to the lane accessing the Museum was still ongoing in the 2020s [see here].

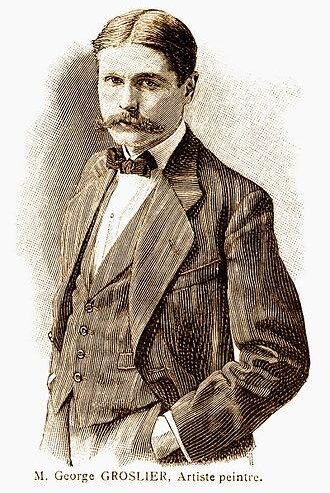

1) George Groslier portrayed in 1913 in the French journal Femina. 2) George Groslier hodling a Khmer Prajnaparamita statue at his desk in 1926, by Martin Hürlimann (© National Museum of Cambodia).

1) George Groslier portrayed in 1913 in the French journal Femina. 2) George Groslier hodling a Khmer Prajnaparamita statue at his desk in 1926, by Martin Hürlimann (© National Museum of Cambodia).

1) George Groslier portrayed in 1913 in the French journal Femina. 2) George Groslier hodling a Khmer Prajnaparamita statue at his desk in 1926, by Martin Hürlimann (© National Museum of Cambodia).

[based on “Works by George Groslier”, in Cambodian Dancers Ancient and Modern, Kent Davis (ed.), Holmes Beach (USA), DatASIA, 2011: 298 – 303.]

Archeological Publications

Publications on Cambodian Arts and Culture

Misc.

sk काम्बोज kāmboja | prakrit कंबोय | [कम्बुजदेशः kambujadesa, 'land of Kambuja' | oldkh កម្វុជទេឝ, midkh កម្ពុជទេស mkh កម្ពុជា kampuchea, Cambodia