Auguste Rodin and the Cambodian Dancers, 1906

by Angkor Database

Modern art, ancient dance: when Rodin came under the spell of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia.

- Publication

- ADB Documents DAN2

- Published

- 2010

- Author

- Angkor Database

- Pages

- 1

- Languages

- English, French

It is a pivotal moment in Xavier de Lauzanne’s documentary La Beauté du Geste-The Perfect Motion‑ទេពហត្ថា (2021), which opened in Europe in March 2024 after a successful release in Cambodia in 2022: Auguste Rodin’s encounter with the seventy dancers of the Cambodian Royal Ballet when they accompanied King Sisowath I in his first visit to France in 1906.

We’re bringing here new perspectives on this artistic and historic milestone.

Often neglected or plainly ignored by Rodin’s biographers, the encounter with the Cambodian dancers surely was a revelation for Rodin [12 Nov. 1840, Paris – 17 Nov. 1917, Meudon, France], the man and the artist, and might help us to better understand how he related to dance, women, and the “antique arts”.

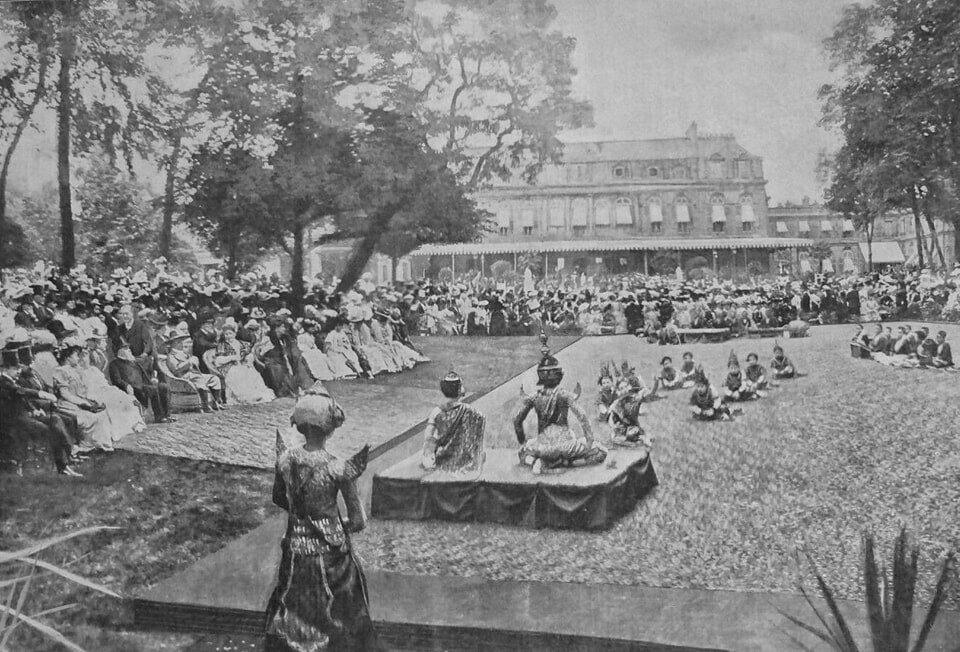

- An important insight is the one given by Anthony M. Ludovici, who became Rodin’s personal secretary precisely in 1906, in his Personal Reminiscences of Auguste Rodin (J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1926, pp 131 – 5, 137 – 9): “The childish naïveté of the great artist was perhaps never displayed to better advantage than on the occasion of King Sisowath’s visit to Paris with seventy native dancers and musicians. It was at the time of the Colonial Exhibition at Marseilles, and this monarch of Cambodia had come with his suite and extensive harem to visit the President of the French Republic. He arrived at Marseilles on June 11, 1906, and came to Paris on the 18th, his harem of dancers following him to the capital on July 1. I believe King Sisowath gave a first display of his royal ballet at the Elysee on July 5, but certainly on the evening of the 10th they performed at the théatre de verdure in the Bois de Boulogne, in honour of the Colonial Minister, M. Georges Leygues, and his guests; and it was to this entertainment that Rodin was invited. I did not see him when he returned that night, but on the following morning he spoke most enthusiastically of the Cambodians, and gave Madame Rodin and myself a glowing description of what they had done. King Sisowath’s corps de ballet, which had performed under the direction of the King’s eldest daughter, Princess Samphoudry, in dances that were at once religious and dramatic, had thoroughly enchanted Rodin, and he compared them with our own modern professional dancers at the Opera and elsewhere, very much to the latter’s disadvantage. He was particularly struck with the manner in which he. declared they created the impression of growing on the stage in their hieratic and rhythmic evolutions, a feat impossible to our toe-dancers, who reach their utmost height at one spring. He also greatly extolled a peculiar serpentine movement of their hands and arms, which they caused to pass like an ondulating shudder from the tips of the fingers of one hand, up the arms, and across the shoulder blades on to the finger tips of the other hand. He declared that he had learnt movements of the human body which he had not suspected theretofore, and which the ancients had either not known or failed to record; and he pronounced the art of the whole display as more consummate than anything he had ever seen. “ Look,” he said, “at that King and at his eldest daughter who directs the corps de ballet I They seem from their features to be wicked people (a juger de leur traits, on dirait qu’ils sont méchants), but how false and delusive our standards must be, if that is the impression they make upon us !

Because they are obviously great artists, and without them all this marvellous beauty would vanish.” When it became known that the Cambodian dancers and their King were to leave Paris for the Villa des Glycines at Marseilles, Rodin in great excitement followed them thither like an enthusiastic child, and there he drew a portrait of King Sisowath, and also made a number of careful drawings of the members of the corps de

ballet. Returning to Meudon three days later he was so thoroughly exhilarated by his experience

that he could hardly speak of anything else. These drawings of the Cambodians must still be in existence somewhere; but, like the rest of Rodin’s drawings, they give the spectator but a poor idea both of the models who stood for them, and of the artist who executed them. By saying this I have no doubt I shall cause a good deal of surprise, if not indignation, among those who are inclined to regard as sacrosanct everything, however trifling, that proceeds from the hand of a great master; but I have the very best authority for writing what I now propose to write concerning the significance of Rodin’s drawings, and that is Rodin’s own account to me of what they meant in the ensemble of his creative activity. Much has been written, and much more has been said about Rodin’s drawings which, judged from the standpoint of the criticism that the

best critics have applied to Rodin’s sculpture, is hardly worth considering. Nevertheless, thanks to the misguided efforts of enthusiasts, there gradually arose a sort of cult in connection with Rodin’s drawings which, I venture to suggest, was as much a surprise to some of his less catholic supporters as it was to the artist himself. Precisely how this cult arose it would take too long to tell. Rodin, however —let it be said

quite frankly — was not sufficiently alert or selfconscious to perceive the whole meaning of what took place. Baffled though he was at first by the sudden vogue for his drawings, he ultimately bowed his head in resignation before the storm of applause that grew ever louder about him, and accepting the verdict of the very experts who had made his greater work intelligible to the world, he, too, slowly became convinced of the

enormous artistic importance of this more trivial side of his productive genius. This complete transformation of Rodin’s attitude towards his drawings, however, only took place some time after I had left him. When I was with him, he was still in the state of one whose mind had not yet been inflamed by the cult, and he spoke about his drawings to me in terms so plain and frank, that there was no mistaking the very small

value he attached to them. I do not mean by this that he affected a carelessness about them which he did not really feel, or that this view of his drawings was of a piece with his generally modest attitude towards his greater works, and that I was therefore deceived; for although Rodin was certainly modest, he had had too great a struggle not to be aware of what was new and inimitable in his masterpieces. I mean that, knowing him as I did, and being in a position to note the difference between his attitude to his sculpture and his attitude to his drawings, I formed the opinion that he regarded his drawings as of no importance whatsoever, except as a

means to an end. He placed them where they belong— that is to say, among the exercises by which he retained the accuracy of his vision for the human form, not among his artistic productions. What scales are to the executant musician, so were Rodin’s drawings to him, no more and no less, and the fact that they happened to constitute convenient vehicles for his autograph when some impretentious friend wished

to be given a small souvenir, never — at least in my time — modified this view of them in his own mind. […] As an instance of the hasty and careless criticism responsible for the great vogue enjoyed by Rodin’s drawings, a writer in L’Illustration declared, when Rodin began drawing the Cambodian women, that very soon we might reasonably expect a sculpture from Rodin representing one of King Sisowath’s dancers. But I wonder what this critic thought when no such sculpture ever came to hand ? And how could it, seeing that the drawings of the Cambodians were never intended by Rodin as documentation for any sculpture which he had in view ? Rodin was much too conscientious to set to work without a model. And if lie ever produced a statuette

of a Cambodian dancer— know of none, though, of course, it may exist— he would only have executed the work with the help of the living model. But let me now report what Rodin himself told me about his drawings; for this is the best justification of all that I have said. Being aware of my connection with the art world, and

familiar also with my own attempts at draughtsmanship, he naturally did not regard my questions as the outcome of idle curiosity. He saw at once that there was something in what I had just witnessed that required explanation, and that I was reasonably puzzled. He therefore replied to my questions very fully, and this

is what he said: “Don’t you see that, for my work of modelling, I have not only to possess a very complete knowledge of the human form, but also a deep feeling for every aspect of it ? I have, as it were, to incorporate the lines of the human body, and they must become part of myself, deeply seated in my instincts. I must become permeated with the secrets of all its contours, all the masses that it presents to the eye. I must feel them at the end of my fingers. All this must flow naturally from my eye to my hand. Only then can I be certain that I understand. Now look ! What is this drawing ? Not once in describing the shape of that mass did I shift my eyes from the model. Why ? Because I wanted to be sure that nothing evaded my grasp of it. Not

a thought about the technical problem of representing it on paper could be allowed to arrest the flow of my feelings about it, from my eye to my hand. The moment I drop my eyes that flow stops. That is why my drawings are only my way of testing myself. They are my way of proving to myself how far this incorporation

of the subtle secrets of the human form has taken place within me. I try to see the figure as a mass, as volume. It is this voluminousness that I try to understand. That is why, as you see, I sometimes wash a tint over my

drawings. This completes the impression of massiveness, and helps me to ascertain how far I have succeeded in grasping the movement as a mass. Occasionally I get effects that are quite interesting, positions that are suggestive and stimulating; but that is by the way. My object is to test to what extent my hands already feel what my eyes see.” - That “serpentine movement” alluded to Rodin was one element of his attraction to Oriental (or “exotic”, as it was often called back then) dance, and writer Edmond de Goncourt noted in his Diary, as early as 23 July 1891: “Walking before dinner, Rodin spoke to me of his admiration for the Javanese dancing-women, and of the sketches he has made of them. He talked, also, of similar studies of a Japanese village transplanted to London, in which were seen Japanese women dancers. He finds our dances too jerky, too much of a hop, while these dances are a succession of movements engendering and producing a serpent-like undulation.” (quoted by Frederick Lawton, The Life and Work of Auguste Rodin, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1906, 472 p, pp 128 – 9)

- In her lengthy and torough work, Rodin: The Shape of Genius (Yale University Press, 1993), Ruth Butler did not mention the Cambodian dancers’ impact on the artist’s worlview, yet she carefully explored his relations to women, debuking the cliché of the sculptor as a predatory, oversexed satyr. About his liaison with sculptor Camille Claudel (8 Dec. 1864, Fere en Tardenois, France – 19 Oct. 1943, Montdevergues Asylum, France), which lasted from 1883 to 1892 [and let’s add here that Camille’s younger brother Paul Claudel, diplomat and writer who expressed utter abhorrence of Angkor in his writings and who was to commit her to the psychiatric ward, had been supported by Rodin at the start of his career], she wrote that after the Vatican added Emile Zola’s Lourdes to its Index of forbidden books, “Rodin wrote Zola that he believed his book gave “radiance to these genuine saints, these girls who had nothing save their devotion, these divine creatures who revealed in all its falsehood that sacrilegious thought that woman is inferior to man.” This is Rodin’s first — though by no means last — “feminist” statement. His respect for women certainly was part of his admiration for [Camille] Claudel and her work. The high point ot the affair between this dynamic and talented woman and the world’s most celebrated sculptor occurred in 1892, in the dilapidated eighteenth century château in the boulevard de l’ltalie called the Folie Payen, where they shared a studio. Claudel’s major work of that year was the pair of nude dancers that [Fine Arts Inspector Armand] Dayot wanted her to drape. By the end of the year, she had agrepub. By the time she showed the pair in the Salon of 1893, the legs ot the female dancer were enclosed in a complicated pattern of flowing drapery, which did not, however, conceal the powerful suggestion of sexual vitality. When Jules Renard saw it in Claudel’s studio in 1895, he said quite simply: “In this group of a waltzing couple, they seem to want to finish the dance so they can go to bed and make love.”” […] ” In the twentieth century, Rodin moved unreservedly to drawing dozens of women models. From his files we know their names — Yvonne Odero, Julia Benson, Dourga le Hindu, Renee Couchet, Nora Falk, Juliette Toulmonde, Marguerite de Fontenay, Carmen Damedoz, Suzic Langlois, Fenella Lovell — and, of course, Gwen John [a British model and artist who dated Rodin from 1904 to 1906, and was to write to him: “Everyone I have ever known before you has wanted to change me.… But you have said that you do not want me to be different than I am.”. Rodin was willing to rescue them from disaster, lend them money, or stand up for them in court. The working conditions in his studio were considered among the best in Paris. One model, identified only as Theresa, tells us that Rodin, who preferred “vigorous, muscular models with salient whipcord sinews, “was “always good hearted,” paid “generously,” and gave them “biscuits and coffee or wine.”” […] The feminist writer Aurel (pseudonym for Aurelie Besset-Mortier), who met Rodin after 1904, found him “too far gone, even a little over the hill” (trop fait, un peu défait), but she regretted that their friendship was Platonic (“une amitie bien pensante”) and that “between him and me there was just gracefulness. ” When he died, Aurel reflected how grateful she was to have lived in the same time as Rodin. In his memory, she wrote Rodin devant la femme (Rodin in the presence of woman), a love poem to Rodin, the artist who saw woman in her strength, not in her weakness.”

- In “His Rodin and The Apsaras” [in Beyond the Apsara, Celebrating Dance in Cambodia, Stephanie Burridge and Fred Frumberg, ed., 242 p, Routledge, 2010] , Thierry Bayle starts his account of the 1906 revelation on a comic, almost surrealist incident: a respectable, bearded man barred entry to the reception given at the Élysee Palace in honor of King Sisowath’s historic visit to France, only because he was not wearing a tie: “On that day of July 1st 1906 the artist fails to be admitted to the garden party of the President of the Republic. Mortified, Auguste Rodin — as it is he, we are speaking of — beats a retreat. Some allude to his anger (at least one article in the International Herald Tribune published on December 29th 2006 on the occasion of the exhibition of Rodin’s drawings at the National Museum in Phnom Penh, organised for the hundredth anniversary of the visit of Sisowath I). When he recalled the incident, Rodin did no seem to give it too much importance. This simple episode could have turned him away from the choreographic art of the Apsaras of Cambodia. Yet it was not to be. Obstinate, the great sculptor would not rest until he discovered the young performers that had come from so far. Nothing would turn him away from the formal enigma of this dance.” […] And his insistence to get closer to the enigmatic Khmer apsaras will bring Rodin to Bois de Boulogne and, a few days later, to Marseille on the Mediterranean coast: “As a visual artist, Rodin can only be filled with wonder by the dance, “a poem unconstrained by any scribe’s tool”, according to poet Stéphane Mallarmé And even more so by the corporal language of Far East than by Western ballet, which he judges too academic. On the evening of July 10th, Rodin makes his way to the “green theatre of the Bois de Boulogne” to find the one who turned him down a first time, maybe in order to be even more sought-after by him. The dance from the fringes of the Colonies is the attraction of the crème de la crème of Paris. […] “On Thursday July 12th, Rodin plays truant. He takes his pilgrim staff and makes his way to Avenue Malakoff, close to the Porte Maillot, along the Bois de Boulogne, where Sisowath Ist resides with his suite and the Royal Ballet in a private mansion. Only a mystical glossary, the one of rapture and of delight, can express the degree of feverish excitement that has struck the artist with the silver beard, who, frenzied, scribbles some sketches of the young nymphs. […] “And it is not over. As the company needs to return to Marseille, where they will perform as part of the Colonial Exhibition before embarking on July 20th, on board of the Amiral Ponty to Phnom Penh, he does not hesitate an instant. In vain he has implored the Director of the Colonies to postpone the date of their departure. Official schedules do not lend themselves to divagations of artists. Surrounded by a verve of smoke, he gets on a train to Marseille on Friday, July 13th. In the rush he left without any tools. He reaches the Phocaean City in the morning of Saturday, July 14th. Due to the public holiday , impossible to find an open shop. He will 5 have to wait until the Monday July 16th to purchase suitable tools. Anyhow, Rodin throws himself into the work with the tools at hand. The difference of quality will be apparent in the works conserved. Without delay, Rodin makes his way to the Villa des Glycines, situated on the road of Mazargues at the Prado, where the royal delegation is hosted. On July 15th, 17th and 18th, he assists, captivated, the performances given at the Château d’Eau of the Grand Palais. He pursues the performers into the garden of the Villa des Glycines. His small favourites respond to the names of Soum, Yem and Sâp. He draws them a capella, without musical background. Touching clichés show the Master at work, sitting on a bench, light-coloured trousers, dark jacket, white hat, the nose clothed in a pince-nez, scribbling on a sheet on his knees, in front of small-sized dancers, immobilized during interrupted movements. In the background, some policemen and a few curious spectators under the trees. Only the chant of birds and the chirring of the cicadas are missing.”

- So, did the fact that the dancers of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia could never been “touched” (decorum, respect for their elevated status) bring to its end Rodin’s artistic impulse of expressing “the movement as a mass”, the density of the female dancer’s body defying gravity? Before the “celestial nymphs who took the beauty of the world with them” when they sailed back to Phnom Penh, Rodin had a powerful encounter with star dancer Isadora Duncan (26 May 1877, San Francisco, USA — 14 Sept. 1927, Nice, France, in a car accident). She recounted it in her autobiography, My Life (Horace Liveright, New York, 1927, Chapter 9): “Since viewing his work at the [1900 Paris] Exhibition, the sense of Rodin’s genius had haunted me. One day I found my way to his studio in the Rue de l’Université. My pilgrimage to Rodin resembled that of Psyche seeking the God Pan in his grotto, only I was not asking the way to Eros, but to Apollo. Rodin was short, square, powerful, with close-cropped head and plentiful beard. He showed his works with the simplicity of the very great. Sometimes he murmured the names for his statues, but one felt that names meant little to him. He ran his hands over them and caressed them. I remember thinking that beneath his hands the marble seemed to flow like molten lead. Finally he took a small quantity of clay and pressed it between his palms. He breathed hard as he did so. The heat streamed from him like a radiant furnace. In a few moments he had formed a woman’s breast, that palpitated beneath his fingers. He took me by the hand, took a cab and came to my studio. There I quickly changed into my tunic and danced for him an idyll of Theocritus which André Beaunier had translated for me thus: “Pan aimait la nymphe Echo, Echo aimait Satyr, etc.” Then I stopped to explain to him my theories for a new dance, but soon I realised that he was not listening. He gazed at me with lowered lids, his eyes blazing, and then, with the same expression that he had before his works, he came toward me. He ran his hands over my neck, breast, stroked my arms and ran his hands over my hips, my bare legs and feet. He began to knead my whole body as if it were clay, while from him emanated heat that scorched and melted me. My whole desire was to yield to him my entire being and, indeed, I would have done so if it had not been that my absurd up-bringing caused me to become frightened and I withdrew, threw my dress over my tunic and sent him away bewildered. What a pity! How often I have regretted this childish miscomprehension which lost to me the divine chance of giving my virginity to the Great God Pan himself, to the Mighty Rodin. Surely Art and all Life would have been richer thereby! I did not see Rodin again until two years later when I returned to Paris from Berlin. Afterwards, for years, he was my friend and master.” Isadora never paid such an homage to the many artists she inspired, like photographer Edward Steichen, visual artist Maurice Denis, sculptor Rik Wouters, and Jewish-Russian-American artist Abraham Walkowitz (28 March 1878, Tyumen, Russia — 27 Jan. 1965, New York City, USA) who met her…in 1906, in the Paris studio of Rodin, who created over 5,000 drawings of Isadora Duncan during his career, and said about her: “She has no laws. She didn’t dance according to the rules. She created. Her body was music. It was a body electric.”

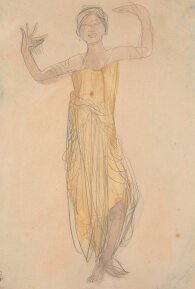

- In closing, the “official” version of this particularly moving and enigmatic moment as it was laid out in the catalogue Rodin and the Cambodian Dancers, His final Passion (Editions du musée Rodin, 2006): “In just one week, he made about one hundred and fifty drawings, re-transcribing or interpreting the ballet poses, with an obvious fascination for the arms and hands of the dancers. These drawings were later highlighted with watercolour, creating coloured harmonies of a rare refinement. The first performance of the Cambodian royal ballet took place in the context of the Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles. Sisowath I had just been crowned King of Cambodia when he undertook the first trip ever to be made by a Cambodian sovereign to France, which had controlled Cambodia since June 1884. This official visit occurred at the height of French colonial expansion. Previously, the Universal Exhibition of 1900 had attracted 48 million visitors. The organisers realised what a tremendous impact this event made on the public, and it was soon adopted as the main tool for colonial propaganda. At the exhibition in Marseilles, the area devoted to Indochina was the largest of the seven sections. When Auguste Rodin met the troupe of dancers for the first time in July 1906, during their brief visit to Paris for an exceptional performance at the Pré Catalan theatre, it was like a revelation to him. He was struck by the timeless and universal nature of the movements of this dance, which transformed this relatively unknown form of art into a manifestation of the universal principle of the “unity of nature” through time and space. This encounter came as such a shock to Rodin that he immediately started a first series of drawings. However, the dancers were expected elsewhere, and Rodin therefore dropped everything to follow them to Marseilles, not even taking with him the necessary paper and drawing material. On arrival, he executed a series of studies of movements and female draperies that are considered to be among the leading lights of his art. “They (the dancers) made the antique live in me (…) I am a man who has devoted all his life to the study of nature, and whose constant admiration has been for the works of antiquity: Imagine, then, my reaction to such a complete show that restored the antique by unveiling its mystery”. The important place Rodin gave to this unique series, exhibiting it in the most prestigious art centres, demonstrates his conviction that he had acquired sufficiently elaborated graphic skills to achieve through drawing — on an equal footing with sculpture — the divine sensuality he venerated so much in the antique. This is the first time that this complete and exceptional series is on public display.

- See also Rodin a l’hotel de Biron et a Melun.

- Read Thierry Bayle’s Rodin and The Apsaras.

Tags: Royal Ballet of Cambodia, Colonial Exhibitions, King Sisowath, dancers, women, French artists, Cambodian dance

About the Author

Angkor Database

Angkor Database — មូលដ្ឋានទិន្នន័យអង្គរ — 吴哥数据库

All you want to know about Angkor and the Ancient Khmer civilization, how it keeps attracting worldwide attention and permeates modern Cambodia.

Indexed and reviewed books, online documentation, photo and film collections, enriched authors’ biographies, searchable publications.

ជាអ្វីគ្រប់យ៉ាងដែលអ្នកទាំងអស់គ្នាចង់ដឹងអំពីអង្គរ, អរិយធម៌ខ្មែរពីបុរាណ, និងមូលហេតុអ្វីដែលធ្វើឲ្យមានការទាក់ទាញចាប់អារម្មណ៍ពីទូទាំងពិភពលោកបូករួមទាំងប្រទេសកម្ពុជានាសម័យឥឡូវនេះផងដែរ។

Our resources include a physical library library at Templation Angkor Resort, Siem Reap, Cambodia.

email hidden; JavaScript is required