Suvarnabhumi, Suvarṇabhūmi, Sovanaphumi

sk सुवर्णभूमि , pl Suvaṇṇabhūmi, kh នសុវណ្ណភូមិ sovanaphum th สุวรรณภูมิ swrnphumi

Suvarṇabhūmi is an Eastern "golden kingdom" often mentioned in ancient Indian literary sources such as the Ramayana and Milinda Panha, as well in Buddhist sacred texts, Mahavamsa and Jataka tales.

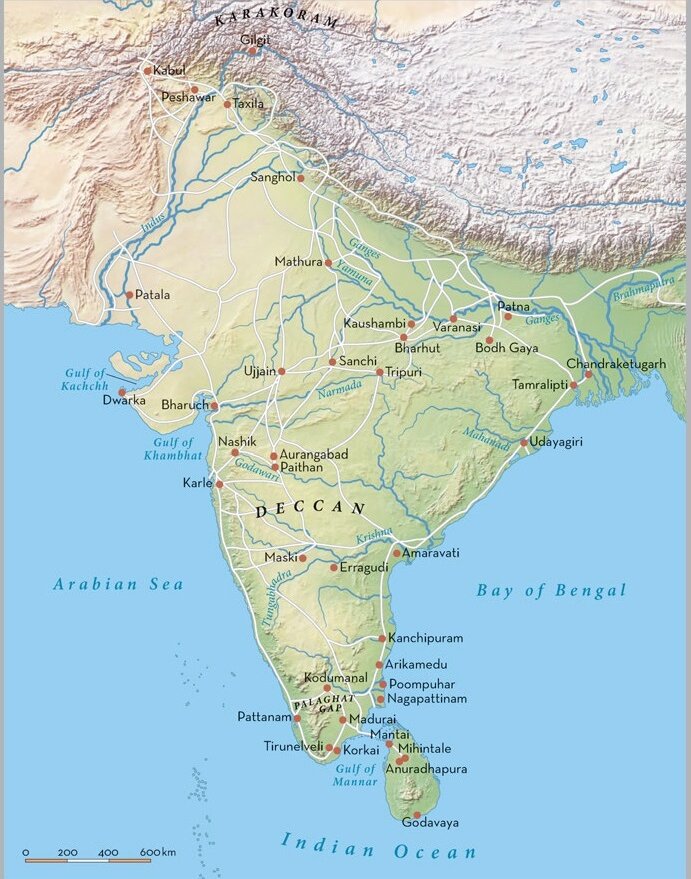

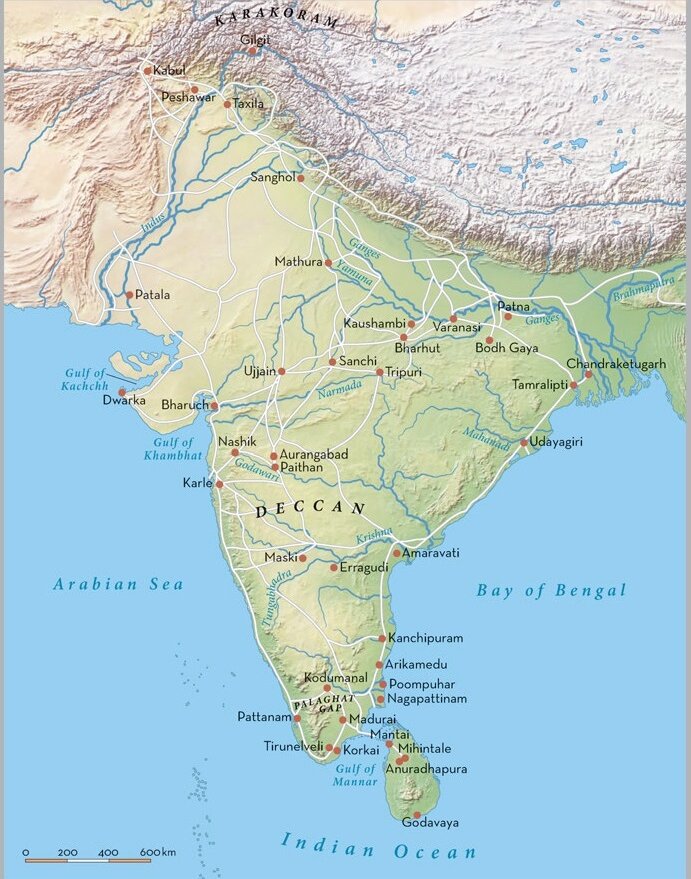

While modern scholars such as Ian Glover insisted that it was an "idealised place", a mythical region akin to the Atlantis or the "Land of Milk and Honey" in Western traditions, the place was an actual destination for Indian traders sailing to the East. Several places in modern Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia, and also Sri Lanka, Sumatra and Borneo, have been speculated to be the genuine location of Suvarnabhumi.

In 2017, Dr. Vong Sotheara from the Royal University of Phnom Penh discovered in Kompong Speu province, Baset district, a stone inscription dating back from 633 CE, written in Sanskrit and Nagari characters, which he translated as: “The great King Isanavarman is full of glory and bravery. He is the King of Kings, who rules over Suvarnabhumi until the sea, which is the border, while the kings in the neighbouring states honour his order to their heads.” The stela is now at the National Museum of Cambodia.

Earlier, researcher George Coedès had suggested that Suvarnabhumi could have been, in its Chinese pronunciation, the root of the word 'Funan', the ancient kingdom in Southern Cambodia.