The Jesuits in Cambodia: A Look into Cambodian Religiousness

by Vanessa Loureiro

How did Franciscan, Dominican and Jesuit missionaries interact with the rulers of Cambodia?

- Publication

- Bulletin of Portuguese-Japanese Studies, vol. 10-11, pp. 193-222

- Published

- June 2005

- Author

- Vanessa Loureiro

- Pages

- 25

- Languages

- English, Portuguese

pdf 246.6 KB

What were the real motives behind the Portuguese and Spanish presence in the Kingdom from the second half of the 16th century to the first quarter of the 18th century? Here are the most salient remarks from this well-documented study:

- Commercial ambitions behind religious zeal: “Diogo do Couto conveys an idea of the importance of the Cambodian ports within the commercial circuits of the Indochinese Peninsula when he reports that in 1551, on the occasion of the Malacca siege by a coalition of the Muslim princes, an emissary to Patan [was sent] with the aim of warning the vessels that arrived from Siam, from Cambodia and from other places in Southwest Ásia, in the direction of the fortress, not to go into the hands of the enemy (Diogo do Couto, Década VI, Lv. 9, Cap. 8, Lisboa, Régia Oficina Tipográfica, 1782).”

- The fleeting fate of Portuguese religious missions to Cambodia: a) “Friar Gaspar da Cruz was the first Portuguese clergyman to set foot in the Kingdom of Cambodia [in 1555] and to settle here – according to Luís Fróis, “(…) as the king himself requested news from the creator of heaven and land, and of this evangelisation in which the Christians live” -, [soon admitting that] the promises of the king were no more than bait used to attract the Portuguese and their vessels. He quickly convinced himself that the conversion of the Cambodian souls into Christians would not be possible.”

b) “Portuguese clergyman would only set foot again in this region nearly two decades later. In fact, in 1570 when Apram Langara rose to the throne, (…) aware that holding onto the kingdom would only be possible with the aid of the Portuguese, the ruler requested that clergymen and the military be sent and promised the missionaries the conditions to spread the word of God. Even though the number of Portuguese religious men in the Far East was limited, the prelate of the Dominican Order insisted in opening a mission in Cambodia. Thus, in 1582 – 1583, the priests Friar Lopo Cardoso and Friar João Madeira arrived in Lovek.”

c) “The death of Apram Langara and the rising to the throne of Barom Reachea II resulted in the inversion of the religious policy. The new King, with deeply rooted Buddhist beliefs, did not hesitate in “revoking their permission of preaching to the natives of the Kingdom”. Facing a variety of obstacles, Friar Lopo Cardoso tried to abandon the mission but was not authorised to do so by the prelate of the Order (…) Now alone in Cambodia, Friar Silvestre de Azevedo continued with his mission and slowly began to win the amity and protection of the monarch. He became advisor and dignitary of the kingdom, with the title of “Pa” (Father), which gave him the privilege of sitting in the presence of the king and of using a hat, symbols of royal dignity. Barom Reachea II allows him to once again preach the Gospel and build churches, and he even placed a learned man of the court at his service to assist him in the drawing up of the doctrine Mistérios da Fé Cristã in Khmer.”

d) “In 1585, more missionaries arrived in Cambodia: Friar Antonio Dorta and Friar António Caldeira, and then another two Franciscan friars. These five men, with the consent of the king and the opposition of the bonzes, baptised approximately 300 children.25 However, all this empathy shown by Barom Reachea II in relation to Christianity was beyond any doubt because of the need for Portuguese military aid and his good will did not last for long (…) During the same period, two personalities who would take on an important role within the scope of the Siamese invasions, joined the missionaries: Diogo Veloso and Blas Ruiz de Herman Gonzales. The first, in particular, became the King’s favourite and even married into the royal family and was designated by the King as “Adopted Son”. In 1592/1593, fearing the possibility of an invasion by Siam, Barom Reachea II asked for help from Malacca through Friar Silvestre de Azevedo and Diogo Veloso. Never having received a reply, he turns to Manila, and in July 1593 he sent Diogo Veloso with a letter in which he asked for military aid and promised in return, commercial advantages and an area for Evangelisation. This missive left before the entrance of the Siamese troops in the territory and for various reasons, help took long in arriving.”

- What really happened to Friar Antonio da Madalena, who shared the first description of Angkor by an European to chronicler Diogo de Couto? “Siam Preah Nareth invaded Cambodia in April 1594 and occupied Lovek, then holding captive in Siam Friar Silvestre de Azevedo, Friar Jorge da Mota and Friar Luís da Fonseca, as well as three Franciscan friars: Friar Gregório da Cruz, Friar António da Madalena and Friar Damião da Torre. After the release of the captives, only Friar Silvestre de Azevedo returned to Cambodia.” [Indeed, Friar Paolo da Trinidade, in his email hidden; JavaScript is required (completed in 1636; Book 3), notes that “em 1593 foram levados presos a Siao fr. Rodrigo da Cruz, fr. Gregório de San Francisco, fr. António da Madalena e fr. Damiao da Torre, vendo sus vidas em mao de tan cruel tirano, como era el Rei Preto de Siao.”] Da Madalena then sailed from Siam to Goa, where he met Diogo do Couto, and later on perished at sea on his return journey.

- The Jesuits: “Cambodia only attracted the attention of the missionaries of the Company of Jesus after merchants from Macao settled in the kingdom seeking alternative port areas due to the constant Dutch ambushes on the traditional routes which linked Macao to India and to Japan. Therefore, after sending missionaries to Cochinchina,

the College of Macao in 1616, sent Father Pero Marques, accompanied by a Japanese brother, to explore the possibilities of opening a mission in Cambodia (…) In fact, the Portuguese authorities only became directly engaged in the mission after the expulsion of the Jesuits from Japan. However, conscious of the sturdy roots of Theravada Buddhism in Cambodia, and that the natives were more interested in gaining access to commerce with the Portuguese

than in getting to know the word of Christ, these priests limited their work to the Christians who were settled in the kingdom and others who disembarked occasionally, specially the Japanese.”

Bottom line: “174 years after the first Portuguese priests stepped into the kingdom of Cambodia, the religious beliefs of its natives remained unchanged. In almost 150 years of missions, Dominicans, Franciscans and Jesuits managed only to widen the restricted circle of the Christian community beyond the Europeans, some Japanese merchants, Conchinchina people and Malay. The few Cambodians which converted to Christianity never reached twenty and even those, shortly afterwards, embraced their original religion.”

ADB input:

- In his Conquista… (op.cit., Libro I, Cap. 70), Friar Paolo da Trinidade makes an important observation: “...como lemos da cidade de Angor no Reino de Cambaia onde havia um templo de nove claustros no qual se acharam mais de doce ídolos, todos de oro maciço, e alguns deles como meninos de dez anos.¨ […as we read of the city of Angkor in the Kingdom of Cambodia, where there was a temple of nine cloisters in which more than twelve idols were found, all of solid gold, and some of them less than ten years old.] Since this account was written around 1630, it shows that that Angkor Wat was far from neglected as a worship center, or “left to the jungle”.

- The Spanish Dominican missionary Gabriel Quiroga de San Antonio wrote an extended account of his voyage up the Mekong River at the beginning of the 17th century to spread the Lord’s word and provide Philippines’ King Don Philippe with an assessment of the region’s colonial potential.

- To quote the essay “Gold, Swords and The Cross: Christianity In Cambodia 1500−1700” (CNE, 2021), “some sort of uprising against the European presence began, which ended with the killing of hundreds of Chinese merchants and the usurper king Preah Ram I at the hands of the Spanish. The young son of the now dead former king, who had been living in exiled in Laos, was returned and put on the throne by the Europeans, who were granted a protectorate in the areas of Takeo and Prey Veng. Trouble continued to brew, and in 1598 the Spanish fleet was ambushed by a well-organized group of Malay, Cham and Chinese on the Mekong, and all but annihilated. The Philippines Governor Pérez Dasmariñas refused to send reinforcements, but authorized a group of volunteers to travel to Cambodia in a donated ship. A Dominican friar, Alonso Jiménez, was also sent to Longvek with a contingent of merchants interested in establishing the church and business.”

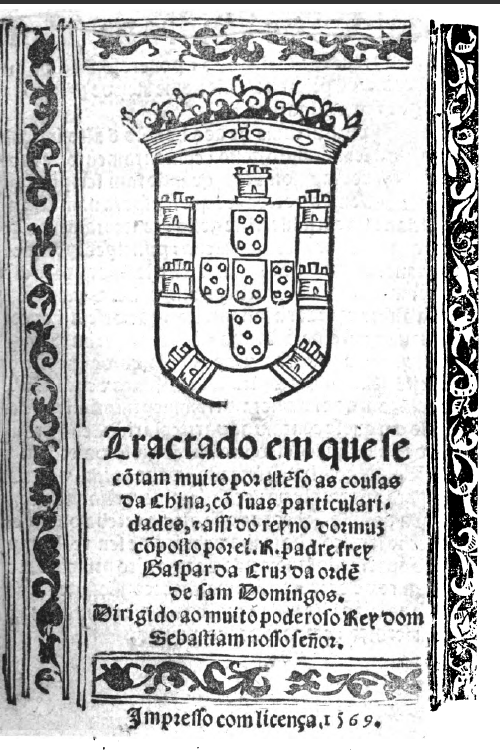

Photo: Cover of the Tractado em que se contam muito por estenso as cousas da China com suas particularidades e assi do Reyno Dormuz dirigido ao muito poderoso Rey Dom Sebastiam Nosso Señor, by Friar Gaspar da Cruz, the first Portuguese missionary to set foot in Cambodia in 1555.

Tags: Portuguese missionaries, Portuguese conquerors, Longvek, Spanish explorers, Spanish conquerors, Siam, Lao

About the Author

Vanessa Loureiro

Potuguese historian Vanessa Loureiro is a consultant and executive officer with several companies and institutions.

To her MBA in History from Universidade Nova de Lisboa, and a doctorate from Paris I University (Panthéon Sorbonne), Vanessa Loureira added masters in management and finances from the Católica and Nova universities.

She has been active in promoting women in educational and leadership programs.