The Work of the Japanese Specialists for New Khmer Architecture in Cambodia

by Kosuke Matsubara

How Japanese researchers' interest in Angkor Wat and traditional Khmer houses led to the involvement of Japanese architects in the New Khmer Architecture.

- Publication

- in HISTORY-URBANISM-RESILIENCE, 17th IPHS (International Planning History Society) Conference, Volume 01, pp 251-259 | Delft, The Netherlands, July 17-21, 2016.

- Published

- 2016

- Author

- Kosuke Matsubara

- Pages

- 9

- DOI

- http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/iphs.2016.1.1203

- Language

- English

pdf 1.1 MB

Paris (and Algiers), Angkor, Tokyo: here is the unexpected triangle subjacent in the remarkable contribution of Japanese architects to the New Khmer Architecture movement of the 1960s. In this study, the author focuses on the contribution of three of them, in close collaboration with Cambodian visionary architect Vann Molyvann: Gyoji Banshoya, Nobuo Goto, and their common mentor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology (TIT), Kyioshi Seike. Excerpts:

“Born in 1930 in Tokyo, Gyoji Banshoya studied at the Tokyo Institute of Technology (TIT) under the supervision of the famous Japanese architect Kiyoshi Seike. After his graduation and realization of his first masterpiece, the Square House characterized by its one-pillar structure, he went to Paris in 1953 with the scholarship from the French government. He studied modern architecture under the mentorship of George Candilis, Vladimir Bodiansky and Gerald Hanning. Following Hanning, Banshoya then went to French-ruled Algiers and worked for the planning agency for some years to become a French modernist architect. Hanning finished his work in Algiers in 1959 and then started to work for the Service of Urban Planning and Housing in Cambodia as UNDP specialist for 4 years.

“In January 1962, Banshoya was also appointed as a UNDP technical assistance officer thanks to the recommendation by was his ex-supervisor Hanning, and was sent to the Direction of Urban Planning of the Ministry of Public Enterprise and Information in the Kingdom of Cambodia2. Just after gaining independence from French Indochina in 1954, Cambodia had asked the United Nations to cooperate in the reconstruction of their new capital. His main counterpart was Vann Molyvann who graduated from the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Banshoya’s mission was only for one year, and he worked as a member of a team led by ATBAT members, just as he had in Algiers.

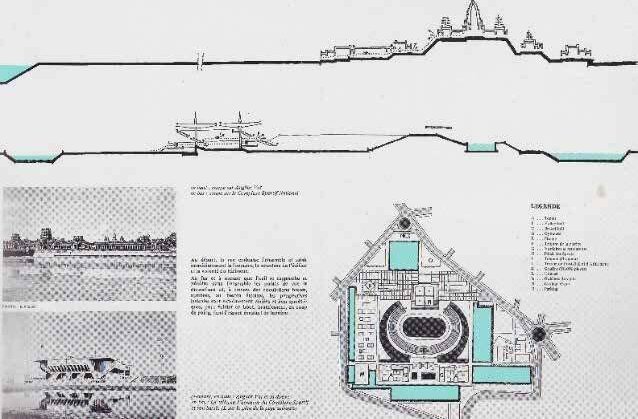

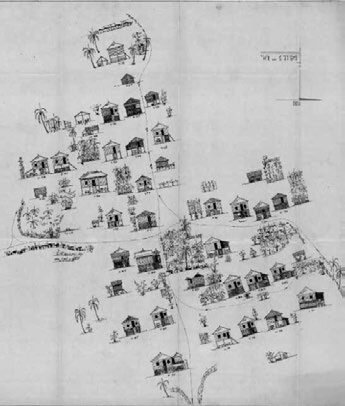

“Here, Banshoya met a man eight years his junior, Nobuo Goto, who also graduated from TIT. He would later become Banshoya’s most trusted collaborator in Damascus. Goto, who soon joined them, was so strongly fascinated by the project in Cambodia, especially the Olympic Stadium, that he dropped out his graduate program at TIT. Seike stated that he nicknamed Goto “Kume Sennin (an unworldly man from Kume)”, because he frequently traveled and never settled down. Kume is a name of place in Japan where Kume Sennin used to live. There is a legend saying the origin of Kume is from Khmer. That is why Seike gave him this nickname. After this first visit in Cambodia, he started his own field work about traditional Khmer houses in Phnom Penh and Angkor Wat. Later, he went to Damascus to support Banshoya elaborate the master plan of 1968, and then went to Paris to work for French planner Michel Ecochard’s office.

According to Seike, one reason why Banshoya and Goto went to Cambodia was the fact that Michio Fujioka (1908 – 1988)had been carrying out an architectural investigation in Cambodia during and after the World War II. Fujioka was a great architectural historian at that time and he wrote some books about Angkor Wat. As an intellectual at that time, Fujioka recognized the importance to introduce Japan to the culture of Cambodia under French rule. Becoming a TIT professor of after the war, he taught architectural history, including his research on Khmer architecture. And for certain, Banshoya and Goto, who were the TIT students, learned plenty of knowledge in his lecture about this oriental culture which was still largely unknown in Japan, and became interested in Cambodian architecture.”

The study details how these Japanese architects studied Angkorean architecture and Khmer traditional housing, in particular around Sihanoukville and in the Cardamom Mountains, inspiring the Cambodian architects of the New Khmer Architecture to go along that way.

Survey of a Cardamom village; Angkor inspiration for Phnom Penh Olympic Stadium, 1964

The author concludes: “These French-influenced Japanese architects always tried to cherish the historical composition of space and incorporate it in their modern planning policy. In concrete, Banshoya’s first piece “the Square House” was a low cost house which harmonized Japanese tradition and modernism. His work in Algiers titled “Temporary Housing Replacing Tin-Roofed Shelters” was also adopting the traditional housing plan with patio supporting the separation of public and private. And here in Cambodia, under Banshoya, Goto tried to reconstitute the spatial composition of traditional Khmer house and suggested the plans of modern Khmer house and housing area.”

Tags: Japanese researchers, Japan, Algeria, architecture, New Khmer Architecture, 1960s, French architects, traditional houses, Angkor studies, modern architecture

About the Author

Kosuke Matsubara

Matsubara Kosuke (b. 1973, Kanagawa, Japan) is Associate Professor of the Department of Social Engineering, University of Tsukuba, Japan.

He completed the Environmental Design Program of the Graduate School of Media and Governance, Keio University, and received his Ph.D. He specializes in the history of urban planning in the Middle East and North Africa.

He received the Prize of The City Planning Institute of Japan, and the East Asia Planning History Prize of the International Planning History Society.