From Bungalow d'Angkor to Hotel des Ruines to Auberge Royale des Temples: 1909-1976

by Angkor Database

The six-decade history of the one and only accommodation inside Angkor Archaeological Park.

- Publication

- ADB Reference Documents HISSR4

- Published

- 2023

- Author

- Angkor Database

- Language

- English

here did archaeologists, draughtsmen, photographers, architects sleep on the Angkor site during the pioneer times? From Captain Auguste Filoz’s Cambodge et Siam, a relation of his 1871 tour helping the Delaporte mission to prepare the first plaster mouldings of Angkor Wat bas-reliefs, we learn that they accommodated themselves right inside the temples, in a sometimes awkward cohabitation with Cambodian bouddhist monks.

But then, the need for a hospitality structure near Angkor Wat became pressing, and here is the history of a rare attempt of a hotel facility right on an archaeological site.

Bungalow d’Angkor

With the expansion of EFEO activities, archaeologists and conservators started to build their own houses in the vicinity of the Bayon, where the first Angkor Conservation compound was to be build. Visitors were lodged there, until French colonial authorities decided a proper residence for visitors should be erected. In a 15 April 1909 letter sent to Henri Cordier by Général de Beylié, then resident-general in Saigon, we learn:

L’hôtellerie d’Angkor Vat, comprenant dix chambres et quatorze lits, sera définitivement terminée le 15 octobre. Les murs seront en briques; chaque chambre aura sa salle de bain; plus tard, on pourra l’augmenter de quatre ou cinq chambres. Il y a un salon et une salle à manger. Les frais (35.000 francs environ) seront supportés par la province de Battambang. On va s’occuper aussi de remettre en état la fameuse chaussée khmère qui va de la rive droite du Mékong à Angkor; cette route, jamais inondée, peut servir en toute saison et a l’avantage de faire voir les plus grandes rivières du Cambodge. Malheureusement le désouchement des arbres qui ont poussé sur cette route sera une grosse affaire. La Société des Études indo-chinoises va charger M. Commaille, conservateur des ruines d’ Angkor, de faire un guide pratique franco-anglais pour ces ruines ; on le fera imprimer à Paris avec 50 ou 60 illustrations, format de poche.” [“the Angkor Wat Hotel, comprising ten rooms and fourteen beds, will be definitively finished on October 15. The walls will be made of bricks; each room will have its own bathroom; later, it will be possible to expand it by four or five rooms. There is a lounge and a dining room. The costs (approximately 35,000 francs) will be borne by the province of Battambang. We will also take care of rehabilitating the famous Khmer roadway which goes from the right bank of the Mekong to Angkor; this road, never flooded, can be used in all seasons and has the advantage of showing the largest rivers of Cambodia. Unfortunately the clearing of the trees that have grown on this road will be a big deal. The Society of Indo-Studies Chinese authorities will commission Mr. Commaille, curator of the ruins of Angkor, to produce a practical Franco-English guide for these ruins; we will have it printed in Paris with 50 or 60 illustrations, pocket format.” [Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 53ᵉ année, N. 5, 1909, pp. 353 – 354]

1) “The Bungalow” as shown on a colored glass panel part of a Angkor Magic Lantern from the 1920s. This panel is mislabeled, as it represents in fact the pagoda (vihear, pavilions and lodging quarters) southeast of Angkor Wat. (available on ebay in December 2023).

1) “The Bungalow” as shown on a colored glass panel part of a Angkor Magic Lantern from the 1920s. This panel is mislabeled, as it represents in fact the pagoda (vihear, pavilions and lodging quarters) southeast of Angkor Wat. (available on ebay in December 2023).

1) “The Bungalow” as shown on a colored glass panel part of a Angkor Magic Lantern from the 1920s. This panel is mislabeled, as it represents in fact the pagoda (vihear, pavilions and lodging quarters) southeast of Angkor Wat. (available on ebay in December 2023).

The French authorities hastened the erection of modest bungalows to accommodate Governor-General (1908−1911) Antony Wladislas Klobukowski and his entourage for the celebrations of the restitution of Angkor attended by King Sisowath in October 1909. Reading EFEO administrative reports, we can figure out how deeply connected were the archaeological and restoration efforts on one side, and the push for tourism development. For instance,

M. Outrey, Résident supérieur au Cambodge, a mis à la disposition des visiteurs d’Angkor des chevaux, des éléphants et même une automobile à 12 places. Il a d’autre part chargé un peintre de talent, M. Groslier, de faire une affiche destinée à faire connaître Angkor. Le bungalow élevé près d’Angkor-Vat s’est augmenté d’une annexe. Enfin, les bonzes ont évacué la bonzerie qu’ils occupaient dans Angkor-thom au N.-O. du Bayon, et l’ont remise à M. de Mecquenem sous la double condition qu’il l’aménagerait en sala pour les voyageurs et qu’il assurerait l’entretien de la pagode abritant la grande statue de Buddha. [Mr. Outrey, Senior Resident of Cambodia, made horses, elephants and even a 12-seater automobile available to visitors to Angkor. He also commissioned a talented painter, Mr. Groslier, to make a poster intended to publicize Angkor. The bungalow built near Angkor Wat has added an annex. Finally, the bonzes evacuated the bonzerie they occupied in Angkor-thom to the N.-W. of Bayon, and handed it over to Mr. de Mecquenem under the double condition that he would convert it into a sala for travelers. and that he would ensure the maintenance of the pagoda housing the large statue of Buddha. [BEFEO, Tome 11, 1911, pp. 467 – 476]

The bungalow was also where the first public sales of ancient Khmer artefacts deemed non-essential by the Angkor conservation or the Phnom Penh Museum to tourists took place. During its September 7, 1922, session, the Comité Cambodgien de la Société des amis d’Angkor — with George Groslier and Henri Marchal in attendance — expressed the wish that

les objets anciens rejetés par la conservation et non acquis par le Musée Albert Sarraut soient vendus aux touristes. Ce système mis en pratique en Egypte rapporte des bénéfices considérables. Les pièces seraient vendues avec un certifcat d’origine délivré par l’EFEO, et les sommes encaissées seraient versées à l’EFEO et destinées à la conservation. Les opérations pourront être effectuées par les soins de la Société. Un dépôt des objets serait mis au musée Albert Sarraut, et il sera nécessaire d’étudier la façon dont la vente pourrait être organisée au bungalow de concert avec la Compagnie des Messageries Fluviales ou par l’intermédiaire d’un de guides officiels de Siem Réap. [ancient artefacts rejected by the Conservation and not acquired by the Albert Sarraut Museum be sold to tourists. This system, put into practice in Egypt, yields considerable benefits. The pieces would be sold with a certificate of origin issued by the EFEO, and the sums collected would be paid to the EFEO and intended for conservation. Operations may be carried out by the Company. A deposit of these objects would be organized at the Albert Sarraut museum, and it will be necessary to study the way in which the sale could be organized at the bungalow in concert with the Compagnie des Messageries Fluviales or through one of the official guides of Siem Réap. [Arts & Archeologie Khmers, t.1, 1923, p 458]

Until 1932, with the opening of the Grand Hotel (now Raffles) in Siem Reap downtown, the Bungalow will remain the main ‘luxury’ accommodation in Angkor area. In its 1927 edition, the famed Guide Madrolle states for “Angkor (Siem-reap): Hôtel-Bungalow d’Angkor, 50 ch. | Hôtel-Palace (en 1927), à Siem-reap, 40 ch. avec salle de bain ou de douche; installation moderne.” And Henri Marchal, in his Archaeological Guide To Angkor 1932 English edition (published by…Alfred Messner), gives the distances of each temple in relation with “the Bungalow”: “Phnom Bakheng, 1 Kil 500 from Bungalow, Baksei Changkrang, 1 Kil 600 from Bungalow.…”

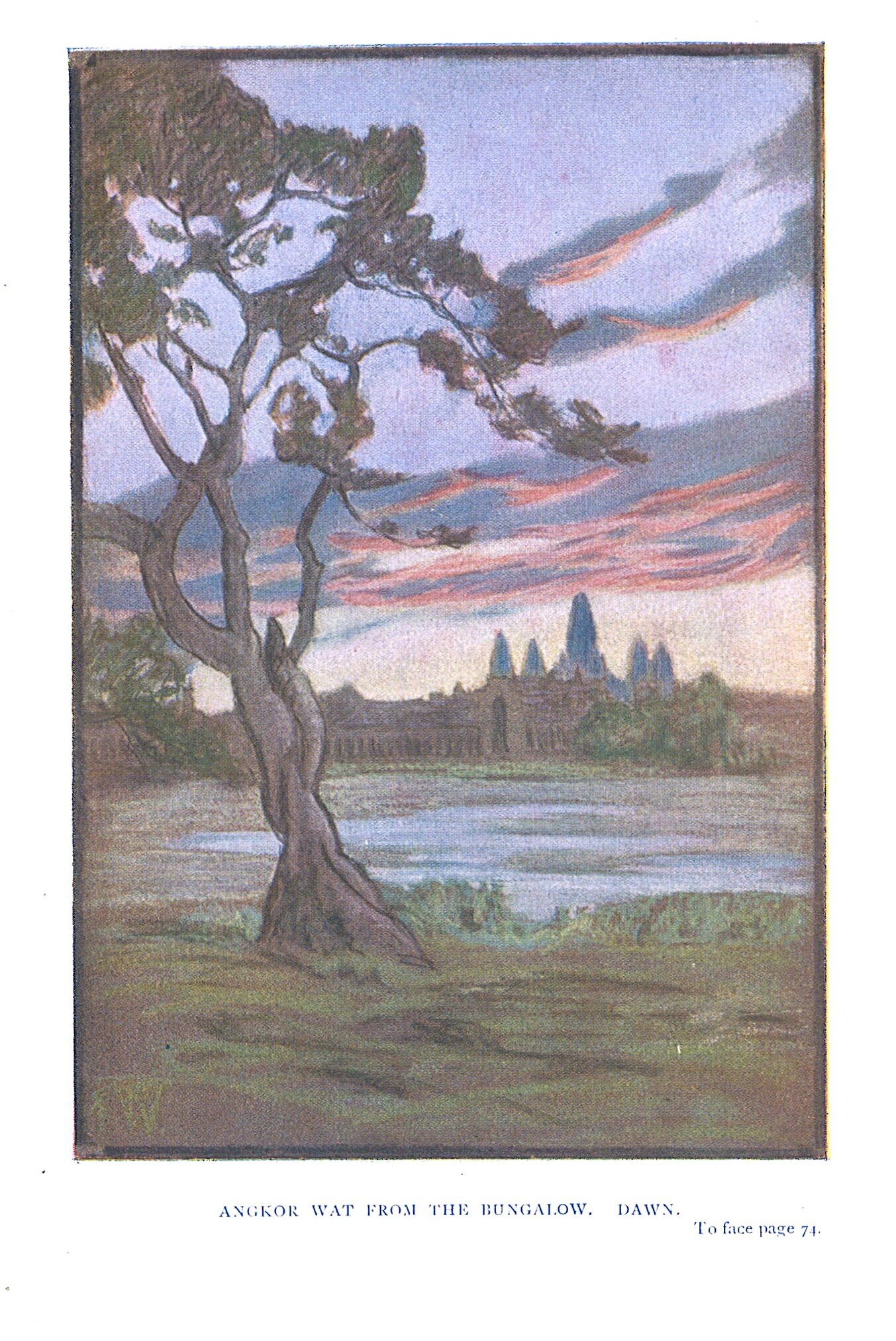

In her Siam and Cambodia in Pen and Pastel (1928), artist Rachel Wheatcroft presented this pastel titled “Angkor Wat seen from the Bungalow at dawn.” She noted: “The excellent little Bungalow Hotel stands just across the broad moat-nearly 700 feet wide and opposite the main entrance so that the view of the temple may be enjoyed at all times, and it is easy to stroll in and out of it.” [p 71]

In her Siam and Cambodia in Pen and Pastel (1928), artist Rachel Wheatcroft presented this pastel titled “Angkor Wat seen from the Bungalow at dawn.” She noted: “The excellent little Bungalow Hotel stands just across the broad moat-nearly 700 feet wide and opposite the main entrance so that the view of the temple may be enjoyed at all times, and it is easy to stroll in and out of it.” [p 71]

Staying there for his visit with his daughters, alongside with George Coedes, Suzanne Karpelès and Henri Marchal, Siamese luminary Prince Damrong Rajanubhab noted in 1925: “The only place to stay here [Siem Reap] was the Hotel Angkor, a single story building like the hotels in Java, but well appointed and comfortable, with both running water and electricity. The food was not bad.” And British painter Rachel Wheatcroft noted in her travel book Siam and Cambodia in Pen and Pastel, published three years later (1928):

The excellent little Bungalow Hotel stands just across the broad moat-nearly 700 feet wide and opposite the main entrance so that the view of the temple [Angkor Wat] may be enjoyed at all times, and it is easy to stroll in and out of it. The walk is longish, across the causeway over the moat to the great portico and galleries, and thence straight on through the immense square to the three terraced stories of the great temple in the centre. [p 54]

Yet French investors and politicians were pushing for the development of hig-end hospitality resources in town, rather than in the vicinity of the temples, even if Georges Garros, the father of aviator and tennisman Roland Garros, remarked in 1923 that “l’accès du magnifique groupe des ruines d’Angkor sera facilité en toute saison par deux routes actuellement en construction de Siemréap et Pursat, vers le Tonlé-Sap : les travaux d’agrandissement du bungalow d’Angkor seront achevés cette année même.” [access to the magnificent group of Angkor ruins will be facilitated in all seasons by two roads currently under construction from Siem Reap and Pursat, towards Tonlé-Sap Lake: the work to enlarge the Angkor bungalow will be completed this very year.”]

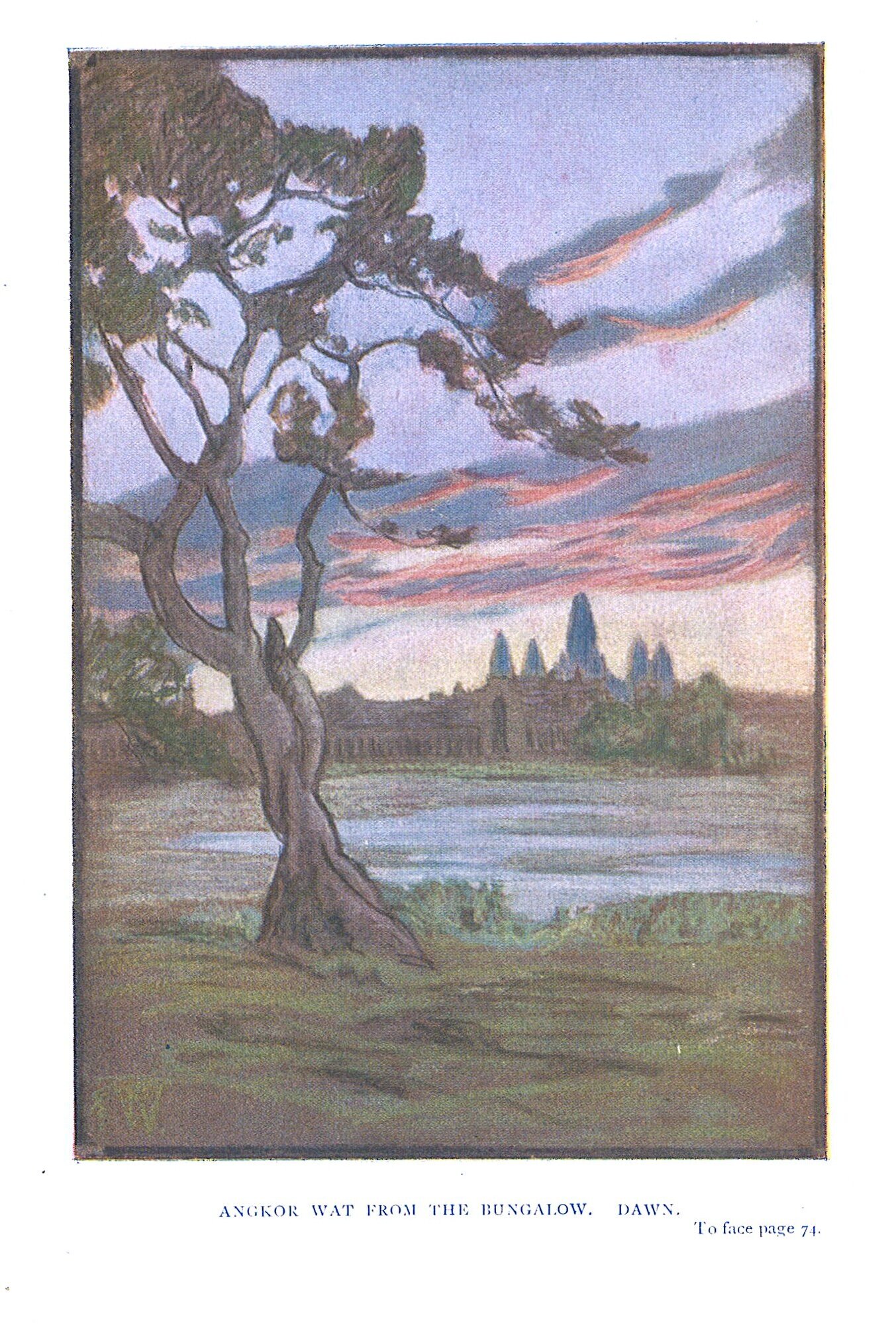

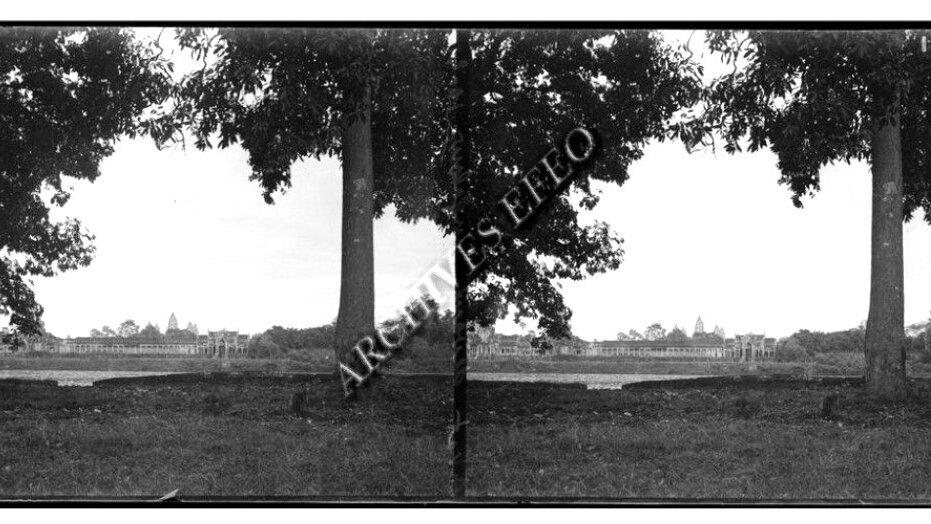

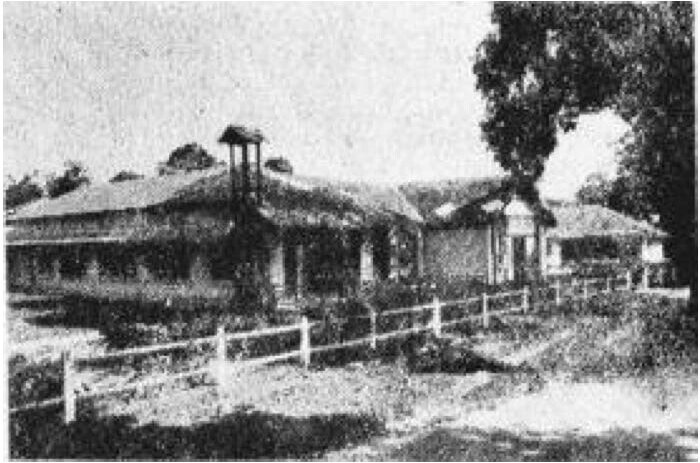

1) This view of Angkor Wat was taken “from bungalow 10 – 31” in the 1920s. Source: Louis Finot Archives [EFEO Photo Collection]. 2) Postcard view of the Bungalow d’Angkor shortly after its completion [Collection Poujade de Ladevèze].

1) This view of Angkor Wat was taken “from bungalow 10 – 31” in the 1920s. Source: Louis Finot Archives [EFEO Photo Collection]. 2) Postcard view of the Bungalow d’Angkor shortly after its completion [Collection Poujade de Ladevèze].

1) This view of Angkor Wat was taken “from bungalow 10 – 31” in the 1920s. Source: Louis Finot Archives [EFEO Photo Collection]. 2) Postcard view of the Bungalow d’Angkor shortly after its completion [Collection Poujade de Ladevèze].

That same year, in May 1923, the newspaper Les Annales coloniales report on the launch of a ‘Société d’études pour la construction d’hôtels en Indochine’ [Planning Agency for Building Hotels in Indochina] and add that

en cours de séance, l’assemblée a formulé son avis sur la construction d’un palace à Xiem Réap [Siemréap]. Cet avis, conforme au sentiment du syndicat d’initiative, se résume ainsi : “Le bungalow actuel d’Angkor peut être conservé et indéfiniment agrandi ; tout autre hôtel doit être édifié à proximité des ruines, mais doit être construit en surface, et non en hauteur, et rester caché par la forêt”.” [During the session, the assembly formulated its opinion on the construction of a palace in Xiem Réap. This opinion, consistent with the sentiment of the Tourism Office, is summarized as follows: “The current Angkor bungalow can be preserved and indefinitely enlarged; any other hotel must be built near the ruins, but must be built on one ground level, without upper floors, and remain hidden by the forest.”]

Complete Excursions, Ruins of Angkor, a bilingual brochure issued by the French Syndicat d’Initiative de l’Indochine-Tourist Office in 1923 witlh several tour options from Saigon, all including a stay at Sala Hotel Angkor with a fixed rate of $12 per day/night.

Complete Excursions, Ruins of Angkor, a bilingual brochure issued by the French Syndicat d’Initiative de l’Indochine-Tourist Office in 1923 witlh several tour options from Saigon, all including a stay at Sala Hotel Angkor with a fixed rate of $12 per day/night.

In 1924, however, the tone has changed: “La Section de Propagande et du Tourisme s’est nettement prononcée pour la construction de l’Hôtel à Siem-Réap et non à Angkor, mais le bungalow actuel d’Angkor serait conservé et même agrandi et passerait de 28 à 50 chambres.”[The Propaganda and Tourism Department clearly supported the construction of the hotel in Siem-Reap and not in Angkor, yet the current Angkor Bungalow would be preserved and even enlarged and would go from 28 to 50 rooms.”] (L’Éveil économique de l’Indochine, 20 April 1924).

Why? In 1923 has been established the Société des Grands Hotels d’Indochine (SGHI), a consortium in which private French entrepreneurs are competing among themselves. Tourism is booming, Angkor is a prime destination and developers understand any major development has to happen outside of the Angkor area.

Said Society is soon rocked by scandals, among them the 1928 embezzlement trial of M. Debyser, with the temporary shut-down of the Bungalow, which will officially reopen in December 1930. [Note: Debyser, who was on trial for a 600 piastres theft, was a notorious drunkard, and the fact that practically all Bungalow’s managers were boozers is documented in different testimonies, up to 1937.]

Famed British journalist Walter B. Harris, who was invited to the ceremony of the coronation of King Monivong in Phnom Penh on 20 – 25 July 1928, noted as he traveled to Angkor to admire the Khmer temples:

After the long motor-bus ride, through scenery of indifferent interest, the arrival at the hotel that the French Protectorate authorities have constructed at Angkor was pleasant indeed. The question of comfort in such a climate as that of Cambodia is one of great importance and the hotel, a part of which was at the time of my visit still under construction, adds not a little to the pleasure of the traveller’s stay at Angkor. The buildings are all on the ground floor, large, cool rooms opening onto wide verandas, encircling green lawns that lead to the moat of Angkor Wat. [East for Pleasure, 1930, p 314.]

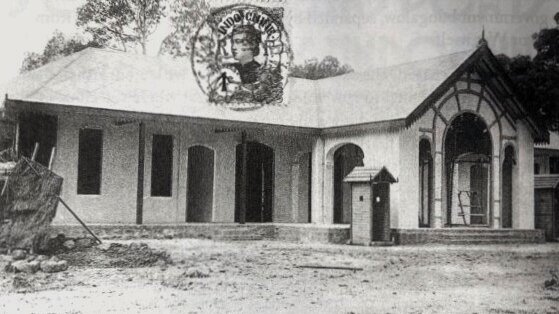

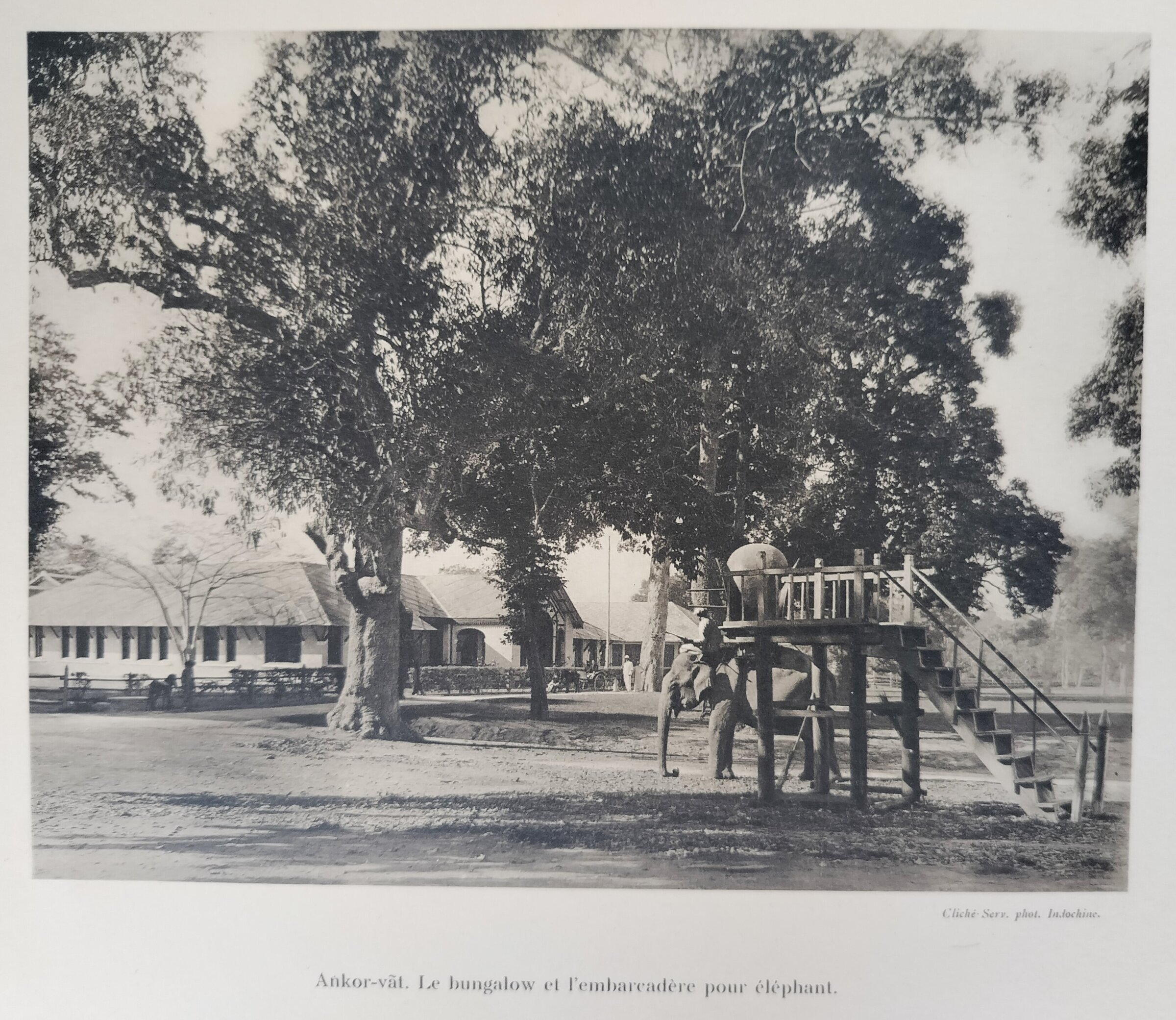

A rare photograph of the Bungalow in the late 1920s, illustrating the chapter ‘Le Tourisme’ by Princesse Achille Murat, née Chasseloup-Laubat, in Un empire colonial francais: l’Indochine, sous la direction de Georges Maspero, Paris, G. Van Oest, 1929, tome II, planche XVIII). Forefront, the wooden platform helping the tourists to hop on elephants.

A rare photograph of the Bungalow in the late 1920s, illustrating the chapter ‘Le Tourisme’ by Princesse Achille Murat, née Chasseloup-Laubat, in Un empire colonial francais: l’Indochine, sous la direction de Georges Maspero, Paris, G. Van Oest, 1929, tome II, planche XVIII). Forefront, the wooden platform helping the tourists to hop on elephants.

(Grand) Hotel des Ruines

With the boom of tourist visits, the former ‘bungalow’ gains the status of full-fledged hotel. But the grand Grand Hotel wants to attract wealthy visitors, and author Harriett Ponder relates in her 1935 – 6 Cambodian Glory how she had to practically fight with the new hotel manager to stay at the Bungalow (then renamed Hotel des Ruines), which she had loved so much at her first visit, as the management wanted to attract travelers to the Grand. A few years earlier, another American writer, Grace Thomson-Seton, was able to stay near Angkor Wat, and recalls her moonlight strolls from Angkor Wat causeway to her room in Poison Arrows.

February 1932: the Hotel des Ruines management is adjudicated to hotelier and entrepreneur Alfred Messner (1880−1943), the owner of successful La Pagode in Saigon and L’Ermitage in Thuduc. Convinced he can expand Angkor Bungalow’s attractiveness, he organizes the first elephant tours of Angkor for tourists, a gimmick that will end only in 2011, under the pressure of animal rights activists. [Note: the retired Angkor captive elephants and their descendants are now living a lush, natural life within the vast expanse of Kulen Elephant Forest.]

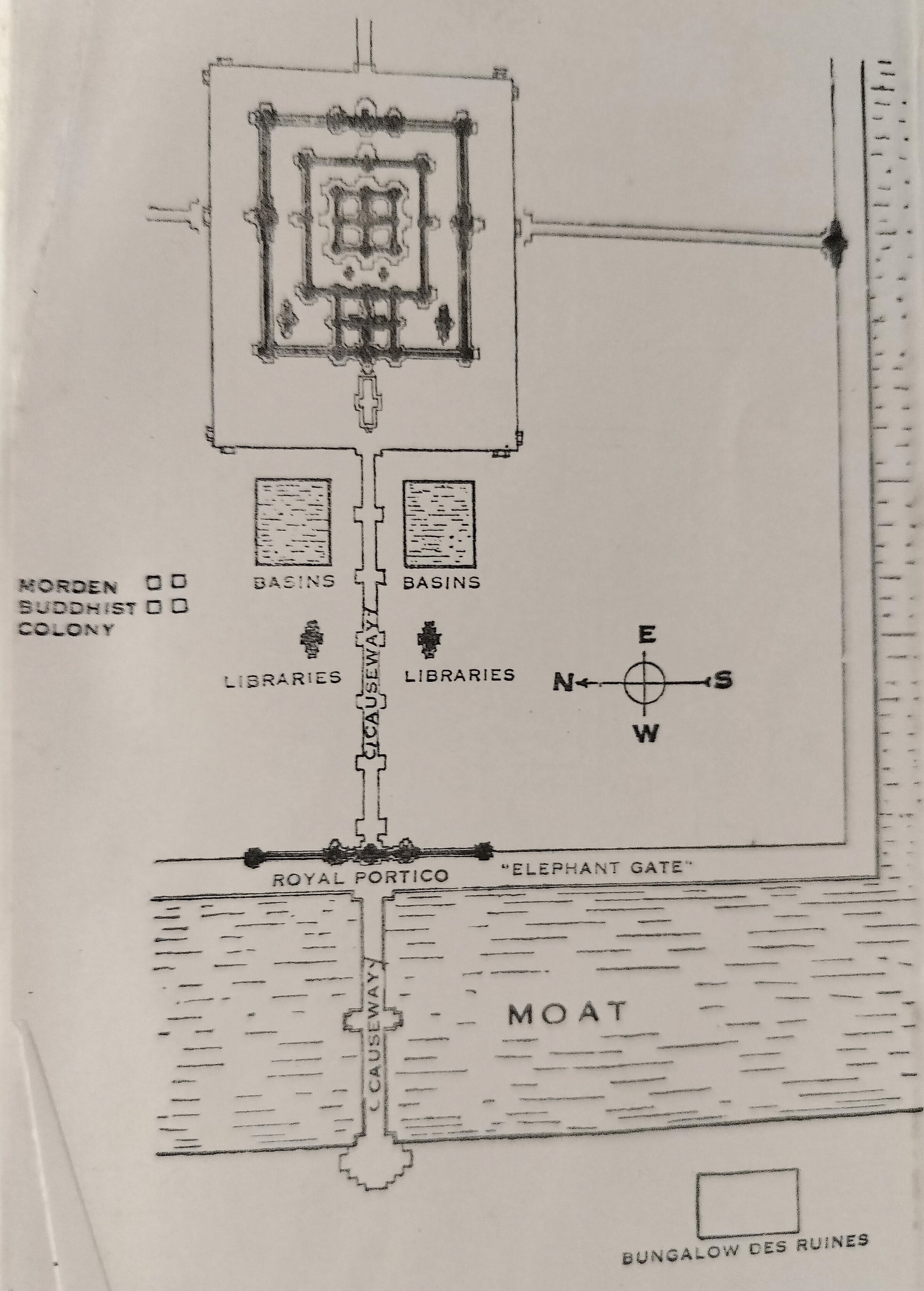

1) In Deane Dickason’s Wondrous Angkor (1937), this plan clearly shows the Bungalow’s location [note the typo on the left side, “Morden” should read “Modern”]. 2) The Bungalow d’Angkor in 1935 [Bulletin d’information économique et sociale].

1) In Deane Dickason’s Wondrous Angkor (1937), this plan clearly shows the Bungalow’s location [note the typo on the left side, “Morden” should read “Modern”]. 2) The Bungalow d’Angkor in 1935 [Bulletin d’information économique et sociale].

1) In Deane Dickason’s Wondrous Angkor (1937), this plan clearly shows the Bungalow’s location [note the typo on the left side, “Morden” should read “Modern”]. 2) The Bungalow d’Angkor in 1935 [Bulletin d’information économique et sociale].

Messner was a workhorse, but when Le Courrier d’Indochine praised him no end, L’Écho annamite on Sept 3, 1928, published a letter from a Japanese customer censuring him for posters set at L’Ermitage swimming pool stating that “Access to the pool is exclusively restricted to Europeans.”

And the competition between French businessmen was raging: in April 1936, André Vergoz, a travel agent founder of the New Siem Reap Hotel, and representative of the Grand Hotel d’Angkor (later Raffles) in Saigon, made sure that Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard stay at the Grand, not at the former Angkor Bungalow.

1) French businessman Alfred Messner. 2) For Angkor lovers…and for hunters: a tourist’s map ordered by Messner showcasing his two hotels in Siem Reap and Angkor.

Later on, after World War II, another issue was the security, due to the Issarak insurgency, particularly active in the Angkor area with the legendary warlord and guerilla leader Dap Chhuon ដាប ឈួន (he was killed by one of his lieutnants while hiding in the Phnom Kulen forests in 1959, according to Charles Meyer in Derrière le sourire khmer (Plon, Paris, 1971). In 1951, Norman Lewis wrote in his A Dragon Apparent:

As there was nowhere to stay in Siem-Reap, I had to go to the Grand Hotel outside the town, which draws its sporadic nourishment from visitors to Angkor. I returned to the town — a blistering, shadeless walk of a mile — for occasional meals. In the whole of Cambodia there is not a single Cambodian restaurant. True Cambodian dishes, just as Aztec dainties in Mexico and Moorish delicacies in Spain, are only to be eaten in the market booths and wayside stalls of remote towns, which are the last refuges of vanishing, culinary cultures. While from fear of infection, one dared not at Siem-Reap risk those brilliant rissoles, those strange membraneous sacks containing who knows what empirically discovered tit-bit, there was always a restaurant serving what came vaguely tmder the heading of Chinese food. This is, at least, light, adapted to the climate, and consequently less burdensome than the surfeit of stewed meats inevitably provided by the Grand Babylon hotels of the Far East. The Grand Hotel des Ruines had had several lean years. It was said that one or two of the guests had been kidnapped. The necessity, until a few months before, of an armed escort, must have provided an element of drama not altogether unsuitable in a visit to Angkor. Now the visitors were beginning to come again, arriving in chartered planes from Siam, signing their names in the register which was coated as soon as opened with a layer of small, exhausted flies falling continually from the ceiling. Perking up, the management arranged conducted tours to the ruins. In the morning the hotel car went to Angkor Thom, in the afternoon it covered what was called the Little Circuit. The next morning it would be Angkor Thom again and in the afternoon Angkor Vat. You had to stay three days to be taken finally on a tour ofthe Grand Circuit, Naturally in the circumstances the hotel wanted to keep its guests as long as possible. And even Baedeker would not have found three days unreasonable for the visit to Angkor. There were many remoter temples, such as the exquisite Banteay Srei, thirty kilometres away, which the bus did not reach, as it was doubtful whether the writ of Dap Chhuon ran in these distant parts. The forces of the tutelary bandit seemed to be concentrated in the immediate vicinity. There was a sports field under my window and every morning, soon after dawn, a party of Dap Chhuon’s men used to arrive for an hour’s P.T. Against a background of goal posts, they failed to terrify. They were thin from the years spent under the greenwood tree and as drey ‘knees-bent’ and ‘stretched’, each piratical rib could be counted. Beyond the playing-field and the gymnasts, was the forest, tawny and autumnal, from winch in the far distance emerged the helmeted shapes of the three central towers of Angkor Vat [pp 221 – 2].

Auberge Royale des Temples

After Cambodian Independence in 1953, the then Prince Norodom Sihanouk, as head of state, personally supervised hospitality industry development. In October 1963, Le Monde Diplomatique commented: “Jusqu’en 1955, le tourisme khmer demeura inorganisé ; il lui manquait notamment les moyens essentiels d’accueillir les visiteurs. L’hôtellerie né comprenait que deux établissements de grande classe — sans être luxueux — : l’hôtel « Le Royal », dans la capitale, et le « Grand Hôtel d’Angkor », bâti en 1932 à Siemreap, sous le protectorat, vétuste et démodé.” [Until 1955, Khmer tourism remained unorganized; In particular, it lacked the essential means of welcoming visitors. The hotel industry only included two high-class establishments — without being luxurious: the hotel “Le Royal”, in the capital, and the “Grand Hôtel d’Angkor”, built in 1932 in Siemreap, under the Protectorate, decrepite and out-of-fashion.”]

On 24 August 1959, ending the decade-long rivalry between French private developers, Prince Sihanouk created the Société khmère des Auberges royales (SOKHAR), with a focus on Siem Reap establishments [the Villa Princiere was added to Grand Hotel and Auberge des Temples] and with affiliated destinations in Kampot, Kep, Bokor, and Poncheutong (Phnom Penh). He presided the Board of Directors, which included then Prime Minister Penn Nouth, expert Sonn Voeunsai, Information and Tourism Secretary of State Tim Dong, vice-president of National Parliament Ang Kim Khoan, and his colleague Ky Heng.

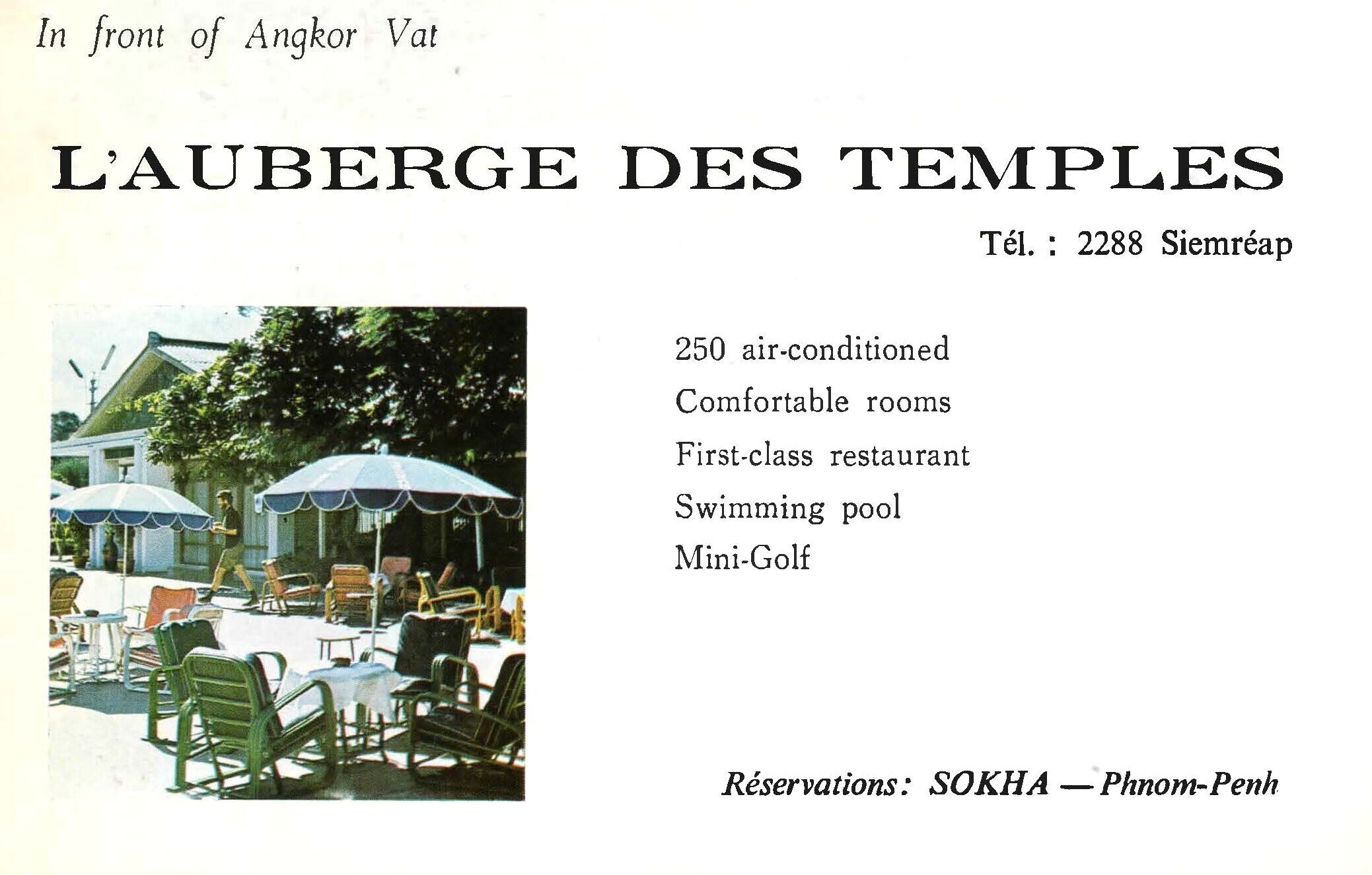

1) An advertisement for Auberge des Temples in the 1950s. 2) “Right in front of Angkor Wat: L’Auberge des Temples”: print ad in Nokor Khmer n 3, April-June 1970 (English edition).

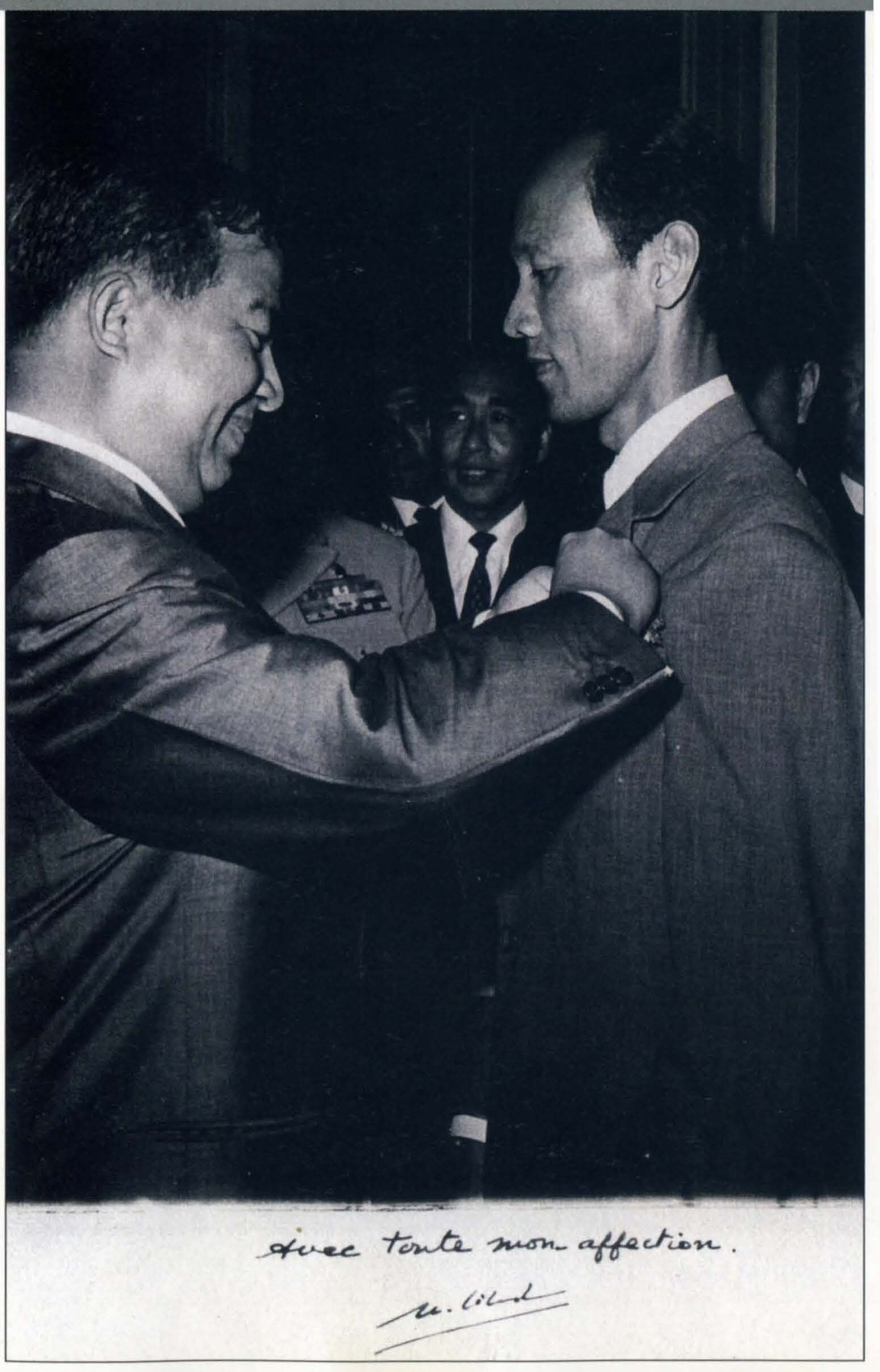

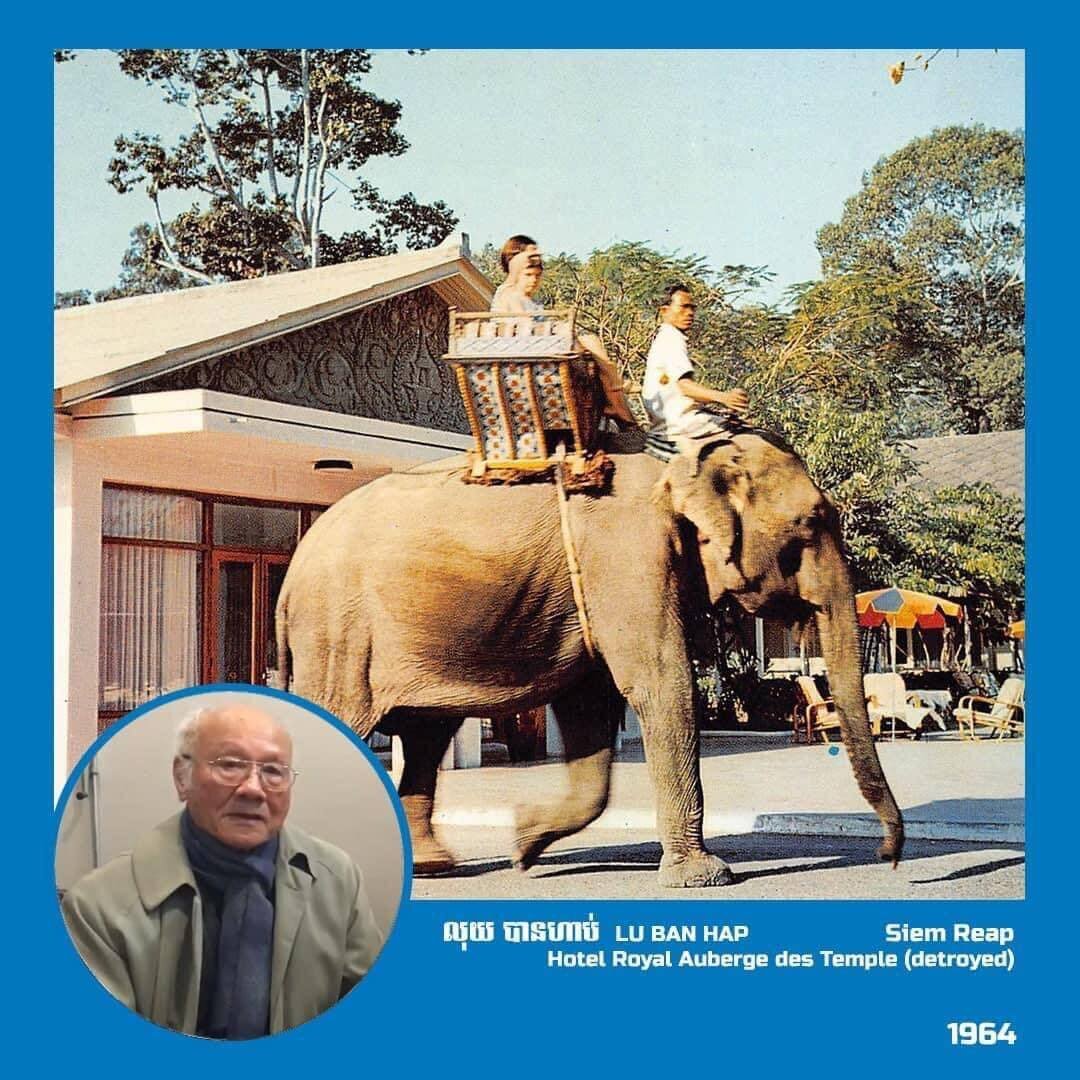

Later on, in 1963 – 4, Plan and Tourism Minister Nhiek Tioulong commissioned renovation works at Auberge Royale des Temples, involving renowned architect Lu Ban Hap (1939, Cambodia — 25 June 2023, France), a leading figure in the New Khmer Architecture movement. Typical of his apportation to the Auberge bungalows are the under-roof natural ventilation and decorated tympanum, a technique he applied to several other buildings including the Svay Rieng Market [information kindly provided by Poum Measbandol]. Lu Ban Hap, who had studied with Vann Molyvann in France and was later decorated by Prince Sihanouk for the conception of the Chenla State Cinema, had married a French citizen, Aurélie Rouard, and moved to France in 1971 with their three children, but he was on the last flight to land in Phnom Penh at the time the Khmer Rouge took over the capital city in April 1975. He survived by escaping with a niece by foot to Saigon.

Architect Lu Ban Hap decorated by Prince Sihanouk in 1969 [photo from Building Cambodia: New Khmer Architecture].

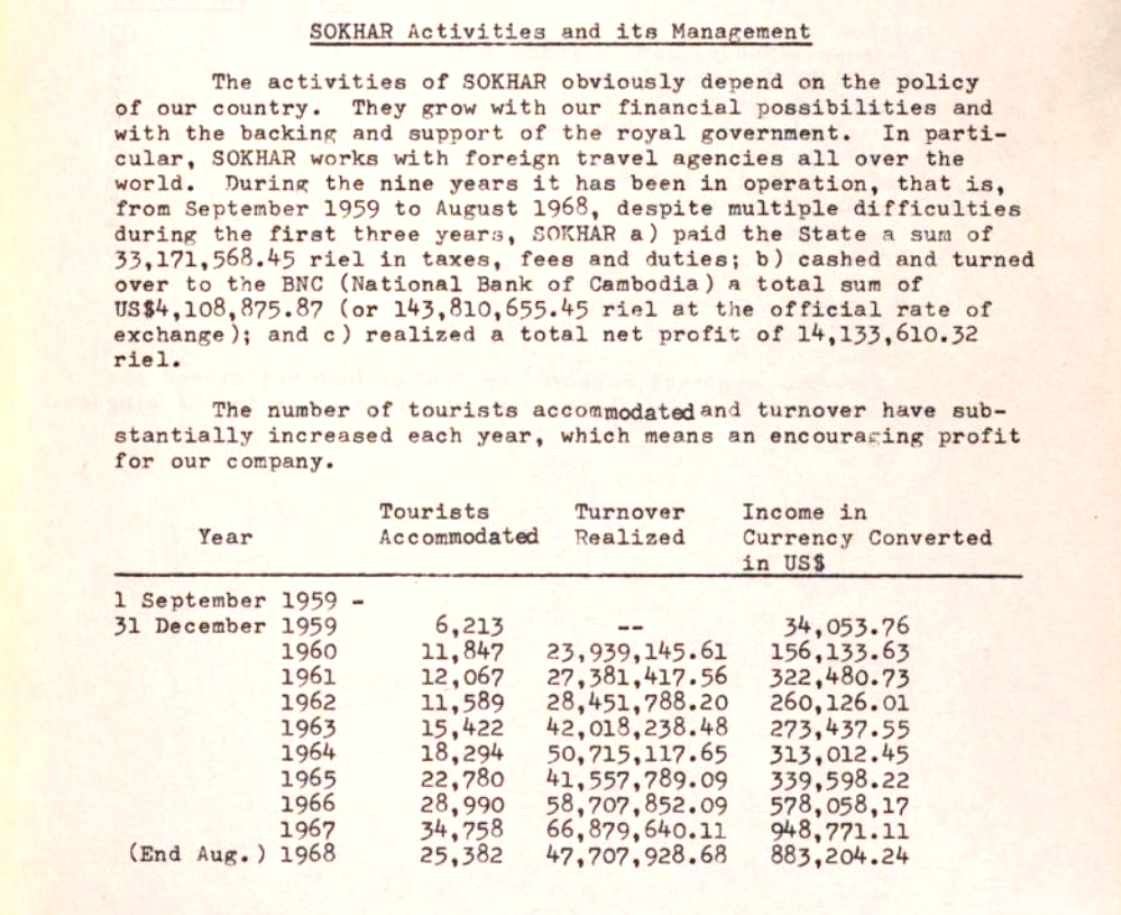

1) The Auberge letterhead in a 19 Dec. 1968 letter written by traveler-photographer Solange Brand. 2) SOKHAR activity report, Dec. 1968.

1) The Auberge letterhead in a 19 Dec. 1968 letter written by traveler-photographer Solange Brand. 2) SOKHAR activity report, Dec. 1968.

1) The Auberge letterhead in a 19 Dec. 1968 letter written by traveler-photographer Solange Brand. 2) SOKHAR activity report, Dec. 1968.

The 1964 works, carried by state-owned building company SONAC, comprised a 42-room extension and creation of a swimming pool for a grand budget of nine million riels. Also contributed to the redesign Roger Colne, an architect and interior designer of French background who was to disappear in the late 1970s, probably killed as he was working as war correspondent. At that stage, according to the reference book Building Cambodia, “the Auberge Royale des Temples in front of Angkor Wat had developed from a small guesthouse for early visitors to the site. By the sixties. it had been enlarged and modernised to cater to those who wanted to gaze at Angkor through the large windows of the dining room. […] SOKHAR managed Auberge Royale de Bokor, Auberge Royale de Pochentong, Hotel Khemara, Hotel Le Royal, Hotel Mondial, Hotel Monorom and Hotel Sukhalay in Phnom Penh. It also ran Auberge Royale des Temples, Grand Hotel d’Angkor, Hotel de la Paix and Villa Princiere in Siem Reap and Motels Krung Preah Sihanouk in Sihanoukville. Another state-owned enterprise, Magasin d’Etat (Magetat), ran the Battambong Motel, the Bokor Palace and Kiri Hotel in Bokor as well as the Angkor Travel Agency, Chaktomuk Night Club, MAGETAT Night Club and Olympic Night Club in Phnom Penh. It also operated the Hotel Independence in Sihanoukville.” [Helen Grant Ross and Darryl Collins, Building Cambodia: New Khmer Architecture, (research assistant Hok Sokol), The Key Publisher Company, supported by the Toyota Foundation, Tokyo-Bangkok 2006, ISBN 974934121X, p 166).

During the ‘Golden Age’ of Cambodia, tourism thrived: SOKHAR registered in its 215 rooms around the country 6,213 guests in September 1959, 22,780 in 1965, and 25,382 at the end of August 1968 (SOKHAR, Internal Report, 1968).

The following years were darkened by civil war, and ultimately destruction. On 11 March 1969, a traveler noted in her blog: “Reaching Siem Reap we changed into a motorcycle pousse for the last 7 km to the Auberge Royal des Temples. The hotel is right opposite Angkor Wat, across the bridge over the “moat”. There were a few buffalo in the water with ibises sitting on their backs.”

The circumstances of the demise of Auberge Royale des Temples remain unclear. On 12 June 1970, French newspaper Le Monde reported that “communist forces occupied the site of Angkor, and that the managers of the hotel, Mr and Ms Dourouze (who was then pregnant), were held as hostages there. Archaeologists Jean Boulbet and Bruno Dagens went to the hotel in a jeep, retrieved the couple and brought them back to Angkor Conservation. They were evacuated to Phnom Penh the day after.

Restaurant With a View - By the 1960s, the little verandah of the Bungalow d’Angkor where Helen Churchill Candee loved to eavesdrop on French after diner conversations had given way to a panoramic restaurant with screen windows directly overlooking Angkor Wat. [screenshots for the promotional documentary Tourism in the Kingdom of Cambodia, 1967.]

Restaurant With a View - By the 1960s, the little verandah of the Bungalow d’Angkor where Helen Churchill Candee loved to eavesdrop on French after diner conversations had given way to a panoramic restaurant with screen windows directly overlooking Angkor Wat. [screenshots for the promotional documentary Tourism in the Kingdom of Cambodia, 1967.]

Restaurant With a View - By the 1960s, the little verandah of the Bungalow d’Angkor where Helen Churchill Candee loved to eavesdrop on French after diner conversations had given way to a panoramic restaurant with screen windows directly overlooking Angkor Wat. [screenshots for the promotional documentary Tourism in the Kingdom of Cambodia, 1967.]

The common belief that it was destroyed by bombardments seems unrealistic since the Khmer Rouge, in spite of their destructive drive, were keen to preserve Angkor temples from destruction. Their pipe dream was to drive back the site to a mythical, pastoral past where paddy fields, not tourists, would prevail. According to Dith Pran [1], who worked as a receptionist at the Auberge from 1964 and had been the year before an interpreter for the British film crew that was producing Lord Jim — the Richard Brooks movie starring Peter O’Toole, James Mason, Eli Wallach and Daliah Lavi — in Angkor, the hotel “was dismantled [by the Pol Pot forces], who used the bricks and stones from the walls to build irrigation works.” [The New York Times, 12 Oct 1979].

1) Stamp of the hotel in the 1960s. 2) View of the Auberge in 1964 with a portrait of Lu Ban Hap as insert [photo card from Building Cambodia, op. cit.].

[1] Dith Pran ឌិត ប្រន (27 September 1942, Siem Reap – 30 March 2008, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) became a photographer and covered the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge with New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg. While suffering the Khmer Rouge, he came up with the phrase “killing fields” to describe the régime’s atrocities. Back to Siem Reap after the 1979 Vietnamese intervention only to find that all his family had been killed, he escaped to Thailand in October, where Schanberg found him and took him to the States, where he joined the New York Times staff. The 1984 movie The Killing Fields directed by Roland Joffé is based on their experiences.

Main photo: Auberge des Temples in the late 1960s, promotion photography.

Tags: Modern Cambodia, modern history, tourism, cultural tourism, civil war, Khmer Rouge

About the Author

Angkor Database

Angkor Database — មូលដ្ឋានទិន្នន័យអង្គរ — 吴哥数据库

All you want to know about Angkor and the Ancient Khmer civilization, how it keeps attracting worldwide attention and permeates modern Cambodia.

Indexed and reviewed books, online documentation, photo and film collections, enriched authors’ biographies, searchable publications.

ជាអ្វីគ្រប់យ៉ាងដែលអ្នកទាំងអស់គ្នាចង់ដឹងអំពីអង្គរ, អរិយធម៌ខ្មែរពីបុរាណ, និងមូលហេតុអ្វីដែលធ្វើឲ្យមានការទាក់ទាញចាប់អារម្មណ៍ពីទូទាំងពិភពលោកបូករួមទាំងប្រទេសកម្ពុជានាសម័យឥឡូវនេះផងដែរ។

Our resources include a physical library library at Templation Angkor Resort, Siem Reap, Cambodia.

email hidden; JavaScript is required