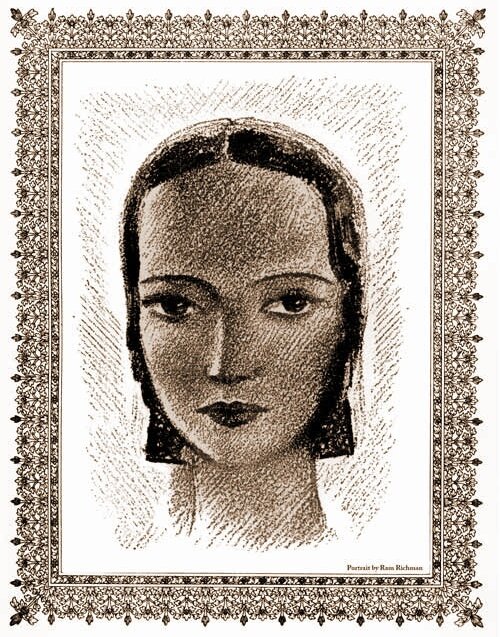

Makhali-Phal

French-Khmer poetess and novelist Makhali-Phal (Nelly-Pierrette Guesde (21 Sep. 1898, Phnom Penh — 15 Nov. 1965, Pau, France) was brought to France in 1906 with the Cambodian Royal Court during the official visit to Exposition Universelle de Marseille, yet wrote almost exclusively about the history, mythology and landscapes of her native country, Cambodia. Her mother was a Cambodian lady, her father, Pierre Guesde, was the Secretary of French Residence-superieure in Phnom Penh in the 1890s.

We do not know for sure what happened to young Pierrette before she arrived in Paris around 1930. Some sources state that she grew up in a Catholic convent at her father’s wishes, other that Pierre Guesde entrusted the child to his parents who lived in Pau (Southwestern France). What seems clear is that Guesde, even if he acknowledged paternity of his Cambodian daughter, was otherwise quite busy with his “legitimate” marriage and his business career.

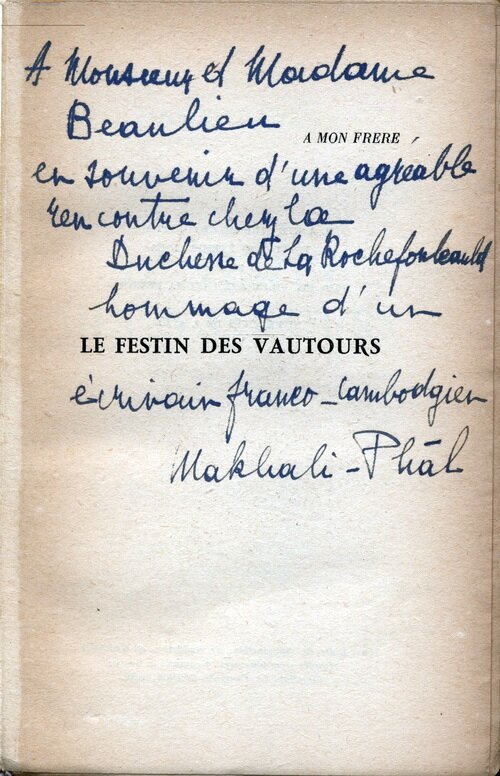

In 1933, she published her first poem, Cambodge, and four years later her Chant de Paix (Royal Library of Phnom Penh and Buddhist Institute), ‘dedicated to the Khmer people’, that has been translated into English (Song of Peace, 2010, DatASIA) and Khmer languages. Her novels such as Le Roi d’Angkor (1952) or Le feu et l’amour (1953) reflect a vast knowledge of the Angkorean civilization, and a sensuality, musicality and mysticism reminiscent of the French symbolist literary movement, with noticeable influences from her Buddhist background — even if her father, Mathieu Pierre Théodore Guesde (a colonial administrator born in Guadeloupe and married to a young Cambodian attached to the Royal Palace, Neang Mali) made her enter a Catholic convent at a young age.

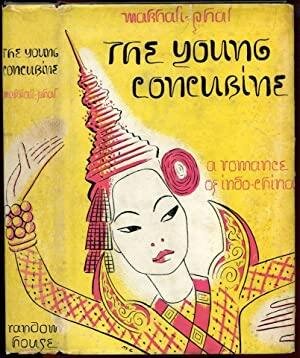

In 1942, the publication by Random House of her novel The Young Concubine made Makhali-Phal a literary celebrity in the USA. The editor noted: ‘Her pen-name, reputedly given to her by King Sisowath, refers to the sound made by the blade of the plow of the goddess Kali. Born in Phnom Penh, Makhali-Phal’s work concerned the perils of metissage (mixed-race identity) n a colonial context. In this novel, for example, a Khmer Princess educated in Paris struggles with her place at the intersection of East and West.’

The poetess who invoked ‘Ô Europe, ô Asie, tristes sœurs jumelles’ (‘Oh, Europe, Oh, Asia, sorrowful twin sisters’) launched ethereal bridges between East and West, although she noted about her work: “Je transposais dans la langue de ma mère le rythme des gongs, les répétitions, les images cruelles, voluptueuses et théologales qui ressuscitaient mes ancêtres d’Angkor et qui m’en délivraient” (“I transposed into my mother’s native language the rhythm of gongs, the repeating echoes, the fierce, voluptuous and mystical images which resuscitated my Angkorean ancestors and yet set me free from them.”)