Angkor Empire: A History of the Khmer of Cambodia

by George Benjamin Walker

Far from cold scientific studies, an endearing invocation of Angkor and its ancient civilization by an Indian historian, poet and master in esoterism.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Signet Press, Calcutta

- Edition

- ebook by gyanbooks

- Published

- 1955

- Author

- George Benjamin Walker

- Pages

- 177

pdf 14.2 MB

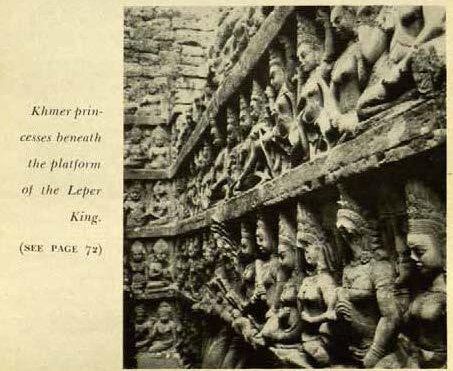

Reviewing this well-documented yet highly idiosyncrasic book in 1960, Bernard Philippe Groslier noted: “Cet ouvrage, fort peu connu en Europe — comme, malheureusement, trop de livres publiés aux Indes — n’est pas dépourvu de mérites. Sous une présentation peu attrayante, et avec en particulier de détestables photographies commemalicieusement choisies parmi les plus mauvaises de la photothèque de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient, il donne cependant un honnête résumé de l’histoire du Cambodge angkorien. C’est même, en dehors de la grande synthèse de L. P. Briggs — assez technique — le seul volume de langue anglaise à peu près correct sur cette question.” [“This work, very little known in Europe — like, unfortunately, too many books published in India — is not devoid of merits. Under an unattractive presentation, and in particular with detestable photographs maliciously chosen from among the worst in the EFEO photo library, it nevertheless gives an honest summary of the history of Angkorian Cambodia. It is even, apart from the great — and quite technical — synthesis by LP Briggs -, the only volume in English pretty much pertinent on that question.”

A tactile, even hedonistic approach of the Khmer ruins, the visit inscribes itself in the Indian historiography while celebrating the specificity of the Khmer culture. Both Chinese and Indian influences are explored within the acknowledgment of the greatness and originality of the Angkorean civilization.

Of note:

- Dance, supernaturality and the sacred: “The Siamese appropriated an immense quantity of cultural material from the Khmers, faithfully copied many of their ancient ceremonials and points of court procedure, and modelled their elaborate hierarchy of officialdom on that of the Khmer state.One thing however the Siamese did not take over: the near-nudity and bare bosoms of the Khmer ballerinas. This was due both to Hinayana Buddhism as well as to Chinese influence, for the prudish Chinese frown upon the baring of the female breasts to the public gaze. The modem Cambodian dance has been infected with this prudery. The dancers are all clothed with due regard for the proprieties.”(p 32)

- Women and society: “Chou Ta-kuan’s [Zhou Daguan] record reveals a society in which women played a conspicuous part. They moved about freely, conducted most of the trade, played an active part in state affairs and often held high political posts, including that of judges. Chinese writers as a whole praise the women or Cambodia, not only for their freedom but also for their knowledge of astrology. and for their acquaintance with political and administrative affairs. Women were free to worship on their own, and could aspire to be religious teachers. We hear of an Uma (wife of Shiva) being fashioned by Indravarman I, and consecrated by the women of the palace. The genealogies or the Khmer kings were matrilineal in character, and so was the succession to the pontificate — both striking facts in a Brahmanical dispensation.” (p 46)

- Scenes of Siem Reap in the 1950s: “We stroll down the banks of the Slem Reap river one warm evening. Tall palms whose graceful fronds wave gently in the breeze; heavy bushes growing wildly on the sloping banks. Big water wheels turning slowly. We pause a moment to watch ingenious water-lifting contraptions. We pass a cluster of pile houses built upon stilts, reminiscent of Indonesia or the South Seas, and primitive bumped bridges like a scene from a Japanose print… a little Chinese pagoda… rice mills with shafts rotated by the gentle current of the river…groups of people bathing in the stream…boys and men…and women. The Cambodian woman is dextrous in changing her wet clothes in public. Sbe will emerge from the water, wet sampot clinging to her body,streth out a graceful brown hand, pick up a fresh sampot from the bank, drape it around her, holding the ends in her teeth, completely remove the wet dress using the dry one as a screen. lt is over in a few seconds. It is a warm, lazy evening. We continue our walk. There is a sudden sound of laughter. We look up. Seated on a projecting ledge of rock are two Cambodian girls. They see us and make no attempt at concealment. Here they are at last; naked to the waist, à la Bali, and shamelessly sitting in the evening sunlight, proud of their youthful forms, two splendid specimens of Cambodian loveliness, like the stone apsaras come to life.” (p 61)

- Sexuality and the “lonely” Zhou Daguan: “Among themselves the slaves freely and frequently indulged in sexual intercourse, but the master of the house would as soon think of copulating with an animal as taking a slave woman to himself. Chou Ta-kuan, who was a lonely Chinese, adds that if anyone, such as a lonely Chinese, who is a guest in the house, sleeps with a slave · woman, the master, if he learns of it refuses to sit with him any more since he has been familiar with a species of the brute creation. This self-righteous prudery did not reflect the sentiments of the common folk, for miscegenation was already far gone when the Khmer Empire was at its peak, and the Moi, or related aboriginal elements, formed a not insignificant section of the population, a view amply confirmed by the evidence of the Angkorean has-reliefs.” (p 7) “[According to Zhou Daguan,] Many persons have mistresses, and some men are to be found who will actually marry women who have served them in this manner. This shocking custom gives rise to no shame or astonishment. If the husband goes away on business for even a few nights his wile will set up a woeful plaint saying that she is not an angel and cannot be exposed to sleep alone. If she takes a lover and the husband dlseovers them in the act, he is allowed by law to punish the guilty man by pressing his feet in a vice until the lover promises him sufficient monetary compensation. Chinese traders like the country, since houses are easy to run and manage, commerce is simple and direct, little clothing is required, rice is plentiful, and women are willing.” (p 89)

Tags: Indian studies, Indian travelers, Angkor Wat, Bayon, Preah Khan, Neak Pean Temple, North Baray, women, dance, nudity, Chinese travelers, Zhou Daguan, sexuality

About the Author

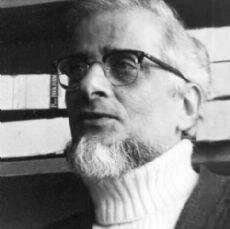

George Benjamin Walker

George Benjamin Walker (also George B. Walker, Benjamin Walker, Jivan Bhakar) (25 November 1913, Calcutta, British India (Kolkata) – 30 July 2013, ?) was an Indian-British author on religion, philosophy, mysticism, a poet, satirist and the first writer to publish an encyclopedia on Hinduism (Hindu World, New Delhi : Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1983).

The son of philanthropist Simeon Walker and physician and suffragette Mary Emily Fordyce, both born in Pune (Poona), Benjamin Walker served as a diplomatic attaché for independent India and spent two years (1950 – 1952)in Vietnam, where he met French publicist René de Berval (the editor of France Asie) and published the first review in the English-language in Saigon, Asia.

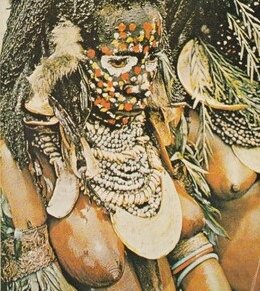

Author of several reference books — in particular Sex and the Supernatural : sexuality in religion and magic (London : Macdonald & Co., 1970) and Encyclopedia of Esoteric Man (Routledge, 1977), Walker was close to the EFEO researchers and took an interest in Angkor and the Khmer Empire, leading to his essay Angkor Empire: A History of the Khmer of Cambodia (Signet Press, Calcutta, 1955), which was reviewed (and corrected on some points) by Bernard-Philippe Groslier.

Cover illustration of the book Sex and the Supernatural.