Comment j'ai parcouru l'Indo-Chine: Birmanie, États shans, Siam, Tonkin, Laos

by Isabelle Massieu

A European woman's view on Southeast Asia at the turn of the 20th century

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Plon, Paris

- Edition

- digital via www.gallica.bnf.fr

- Published

- 1901

- Author

- Isabelle Massieu

- Pages

- 404

- Language

- French

French explorer Isabelle Massieu did not travel to Angkor in 1896 – 1897 as an amateur archaeologist or historian, but as a pleasure part of a long exploratory journey across India, Southeast Asia and China. Her notations are nevertheless precious, bringing us a perceptive and sagacious woman’s view on the male (and often male chauvinist) world of colonized Indochina, Siam and Burma. A few among many important notations:

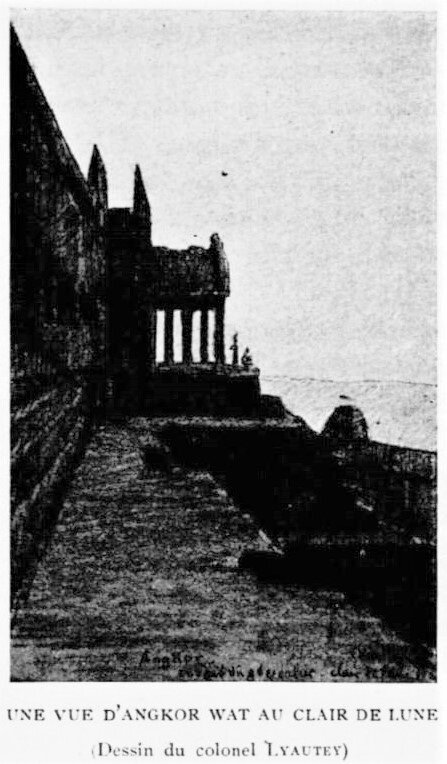

- An acute perception of the sacred status of Angkor for modern Cambodians: ‘Les aspects des phnoms (ainsi nomme-t-on les tours khmers), des galeries et des cours intérieures nous saisissent comme l’évocation d’un autre monde. Derrière les colonnes des galeries, de nombreux bonzes s’abritent, se disséminent et se dissimulent, surveillants silencieux de nos solitaires et nocturnes visites, dans lesquelles nul indigène né se soucie de nous accompagner. Elles semblent être pour eux presque une profanation. Dans cette paix la robe jaune et la draperie d’un moine bouddhiste jettent parfois comme un éclair fulgurant sous la clarté lunaire.’ (p 23) [‘The aspect of the phnoms (name of the Khmer towers), the galleries and the inner courtyards strikes us as the evocation of some another world. Behind the columns in the galleries, many bonzes shelter, scatter and hide away, silent watchers of our solitary and nocturnal visits, in which no native cares to accompany us. To them, they seem to be almost a profanation. In this peace the yellow robe and the drapes of a Buddhist monk sometimes throw like a flash of lightning in the moonlight.’]

- Angkor seen not merely as ruins, playground for Western archaelogist, but as an actual religious site: ‘Un fonctionnaire du Cambodge nous affirme avoir assisté, à minuit, dans la pagode d’Angkor, à une bizarre cérémonie, une sorte d’incantation à la lune. Une lame brillante étincelait dans la main du chef des bonzes, tandis que sa robe jaune semblait dans une phosphorescence. On pourrait trouver dans la légende du pays l’explication de cette scène. Le soleil est le protecteur d’Angkor et la lune est son génie malfaisant. Au temps de la pleine lune les bonzes se livrent en effet à une cérémonie toute de menace à la lune. Il leur faut conjurer ses maléfices qui détruiraient Angkor si la puissance du chef bouddhiste né les dominait. L’épée flamboyante sous la lune existe d’ailleurs, elle a près de deux mètres de longueur, et il faut se mettre à deux pour la brandir.’(p 24) [‘A [French] official tells us that he witnessed a strange ceremony at midnight in the Angkor pagoda, a sort of incantation to the moon. A brilliant blade glistened in the hand of the chief bonze, while his yellow robe seemed phosphorescent. One could find in the local legend an explanation for this scene: the sun is the protector of Angkor and the moon is its evil spirit. At full moon, the bonzes indeed engage in a ceremony clearly threatening to the moon. They must ward off his evil spells which would destroy Angkor if the power of the Buddhist leader did not dominate them. The flaming sword under the moon does exist: it is nearly two meters in length, and it takes two people to wield it.’]

- Angkorean past and modern Cambodians: amnesia or lapse in historic continuity? ‘Sans me permettre les réflexions philosophiqués et les considérations qui né seraient pas de ma compétence, je né saurais passer sous silence le sentiment d’écrasement et de confusion qui saisit tout voyageur devant la splendeur de cet art khmer, dont le type le plus merveilleux, le mieux conservé, est Angkor Wat. On est profondément étonné et attristé de reconnaître que l’on né sait plus rien de cette civilisation et de ce peuple dont les oeuvres parlent, et que les Cambodgiens eux-mêmes ont tout oublié de leur passé. Ils disent que ces prodigieux monuments sont l’oeuvre des anges ou des géants, ou bien qu’ils “naquirent d’eux-mêmes”. Quelques-uns pensent que le secret de cette histoire se trouvera dans la partie obscure et retirée dont j’ai parlé au centre de la tour centrale d’Angkor Wat. Les entrées en ont été murées pour la protéger, avec quelques objets précieux qu’elle renferme, contre les rapines des Siamois. Un fonctionnaire de Kratié qui se donne à l’étude du sanscrit, du pali et des religions hindoues [probably Adhémard Leclere ?] né doute pas que l’on né doive trouver dans le sanctuaire des inscriptions qui nous feront connaître nettement le culte et, avec lui, le temps et l’origine du peuple auteur de ces monuments. Ce qui est certain, c’est que devant ces grandeurs d’Ellora, ce Madura, de Baalbeck, des temples d’Egypte et de ce colossal Angkor, nos architectures, nos oeuvres d’art semblent de proportions bien réduites et notre vie moderne paraît singulièrement étriquée. La brousse envahissant de nouveau nos territoires d’Europe cacherait aisément nos monuments et nos belles cathédrales si le soufflé d’hiver en désagrégeant nos mortiers et nos ciments né devait aussi dépouiller nos feuillages et dévoiler nos ruines.’ (pp 26 – 27) [‘Without allowing myself philosophical reflections and comments which would not be of my competence, I could not avoid to mention the feeling of crushing confusion which seizes any traveler in front of the splendor of this Khmer art, of which the most wonderful type, the best preserved is Angkor Wat. We are deeply astonished and saddened to recognize that we no longer know anything about the civilization and the people these monuments narrate to us, and that the Cambodians themselves have forgotten everything about their past. They say that these wonderful monuments are the work of angels or giants, or that they “were born of themselves”. Some believe that the secret of this history lie in the darkest and most secluded part inside the central tower of Angkor Wat. The entrances have been walled up to protect it, along with some precious objects it contains, against the Siamese plunderers. An official in Kratié who devotes himself to the study of Sanskrit, Pali and Hindu religions [probably Adhémard Leclere?] has no doubt that we should find in the sanctuary inscriptions which will reveals to us the cult, the era and the origin of the people who created these monuments. What is sure is that in front of the grandeur of Ellora, Madura, Baalbeck, the temples of Egypt and this colossal Angkor, our architectural achievments, our works of art seem to be of much reduced proportions, and our modern life seems singularly cramped. The bush again invading our European territories would easily hide our monuments and our beautiful cathedrals if the winter winds, by disintegrating our mortars and our cements, did not also strip out our foliage and reveal our ruins.’]

- A precise description of Tonle Sap Lake eco-system and economic role: ‘La navigation est jolie jusqu’au Tonlé Sap, le grand lac d’Angkor, à soixante kilomètres [by boat, the distance by road being nowadays 113 km from Phnom Penh to Kampong Laeng] de Pnom-Penh. Les rives sont bordées de caï-nhas et de jardins jusqu’au gros bourg de Kampong Leng; puis l’une d’elles s’éloigne et disparaît dans l’horizon plattandis que l’autre reste maintenue par la ligne de montagnes qui se profile dans le lointain et nous sépare du territoire siamois. Le lac souvent tempétueux est au calme, et nous arrivons en vingt-quatre heures au point extrême de la navigation à vapeur. Le Grand Lac mesure 110 kilomètres de longueur sur une moyenne de 25 kilomètres de largeur; sa profondeur varie entre 14 mètres et, à la saison sèche, 1 mètre et même quelques décimètres. Le Mékong en se déversant, comme je l’ai dit plus haut, dans cette dépression y apporte des boues qui exhaussent les fonds. Des documents chinois parlent du Tonlé Sap comme d’un golfe maritime baignant les tours de Banon près de Battambang. Le Mékong en projetant au-devant de l’entrée du golfe sa barre d’alluvions, l’a séparé peu à peu de la mer; puis la crue fluviale l’a transformé en bassin d’eau douce, bassin dont le lit se hausse insensiblement et que les siècles dessécheront un jour. En attendant, des marsouins et des raies vivent encore dans ces eaux, où fourmillent des myriades d’espèces fluviales apportées par les crues; et en certains points des nuées d’oiseaux tourbillonnent au-dessus de ces multitudes grouillantes. Nous devons attendre les pirogues, qui pourront seules continuer sur les hauts fonds et dans la forêt inondée. On dîne à bord avant le départ, pendant un terrible orage, et, la nuit venue, par le beau clair de lune, on se tasse avec ses bagages dans les sampans. Les matelas cambodgiens, qui se replient en accordéon pour faire sièges au besoin, sont étendus à terre et nous permettent d’admirer et de rêver en doux repos. Les sampans se faufilent l’un derrière l’autre à travers de grands arbres, qui laissent émerger l’énorme dôme de leur feuillage, tandis que leurs troncs plongent de plusieurs mètres sous les eaux. Souvent, on entend un bruit de branches sous notre coque nous passons sur des arbres. Bientôt le lac boisé se fait rivière, nous entrons dans la forêt inondée. De longs aréquiers se profilent sur le ciel, et au-dessous se distinguent les sombres feuillages des manguiers, les longues feuilles luisantes des bananiers; puis des bouquets de bambous qui retombent, des palmiers, des cocotiers toute la richesse tropicale. De place en place des lumières apparaissent et se perdent dans la brousse, on entrevoit des villages, des cases sur hauts pilotis. Le courant est très violent, les piroguiers font effort dans le calme absolu de la nature; on navigue comme dans un rêve à travers ce paysage étrange sans songer aux troncs d’arbres qui guettent nos mobiles embarcations. Les sampaniers, si habitués qu’ils soient, se perdent eux mêmes dans ces dédales et l’un des sampans arrive plus d’une heure après nous. A dix heures du soir nous stoppons à Siem Réap. Presque tous, nous devons rester dans nos embarcations, en proie aux moustiques. Les mariniers bavardent, l’orage éclate de nouveau, la pluie fait rage, les indigènes disent que «le ciel tombe»; on se garantit comme on peut, on né se repose guère, et au matin tout le monde, bien dispos néanmoins, se hâte pour aller prendre café ou chocolat dans la grande case disposée pour les réceptions. Nous sommes en territoire siamois. Trois éléphants seulement ont été amenés pour le gouverneur général, et je les aperçois dans l’eau jusqu’aux yeux, la trompe droite dressée, tandis que notre caravane continue dans les sampans jusqu’au point où des charrettes attelées de boeufs nous attendent. La route se perd invisible sous l’eau; les bêtes marchent baignées jusqu’au ventre au milieu d’une véritable forêt d’arbustes et de buissons. Les cahots sont insensés, on tangue et on roule, c’est l’illusion du bateau. On gravit même des marches avant d’arriver et rien né se casse.’ (pp 16 – 18) [‘This is a pleasant navigation to Tonle Sap, the great lake of Angkor, sixty kilometers [by boat, the distance by road being nowadays 113 km from Phnom Penh to Kampong Laeng] from Pnom-Penh. The banks are bordered by caï-nhas and gardens as far as the large village of Kampong Leng; then one of the banks moves away and disappears into the flat horizon, while the other remains fixed by the line of mountains which looms in the distance and separates us from the Siamese territory. The often stormy lake is calm, and we arrive in twenty-four hours at the extreme point of steam navigation. The Great Lake measures 110 kilometers in length by an average of 25 kilometers in width; its depth varies between 14 meters and, in the dry season, 1 meter and even a few decimeters. The Mekong River, by pouring, as I said above, in this depression, brings there mud deposits which raise the bottom. Chinese documents speak of the Tonle Sap as a sea gulf bathing the towers of Banon near Battambang. The Mekong, projecting its bar of alluvium in front of the entrance to the gulf, gradually separated it from the sea; then the river flood transformed it into a basin of fresh water, a basin whose bed rises imperceptibly and which the centuries will dry up one day. In the meantime, porpoises and rays still live in these waters, where swarm myriads of river species brought by the floods; and in certain places clouds of birds swirl above these swarming multitudes. We have to wait for the canoes, which alone will be able to continue on the shallows and in the flooded forest. We dine on board before departure, in a terrible thunderstorm, and, at night, by the beautiful moonlight, we pack our luggage in the sampans. Cambodian mattresses, which fold up like an accordion to make seats when needed, are stretched out on the floor and allow us to admire and dream in a gentle rest. The sampans weave their way one behind the other through tall trees, which reveal the enormous dome of their foliage, while their trunks plunge several meters under the water. Often we hear the sound of branches under our hull as we pass trees. Soon the wooded lake becomes a river, we enter the flooded forest. Long areca palms stand out against the sky, and below stand out the dark foliage of the mango trees, the long glossy leaves of the banana trees; then bunches of falling bamboo, palm trees, coconut palms, all the tropical luxuriant nature. From place to place lights appear and are lost in the bush, we glimpse villages, huts on high stilts. The current is very violent, the boatmen make an effort in the absolute calm of nature; we navigate as in a dream through this strange landscape without thinking of the tree trunks which lie in wait for our mobile boats. The sampaniers, accustomed as they are, lose themselves in these mazes and one of the sampans arrives more than an hour after us. At ten o’clock by night we stop at Siem Réap. Almost all of us have to stay in our boats, plagued by mosquitoes. The sailors are chatting, the storm breaks out again, the rain is raging, the natives say that “the sky is falling”; we protect ourselves as best we can, we hardly rest, and in the morning everyone, nevertheless well-spirited, hurries to go and have coffee or chocolate in the large hut arranged for receptions. We are in Siamese territory. Only three elephants have been brought in for the Governor General, and I can see them up in the water, right trunks erect, as our caravan continues in the sampans to the point where ox-drawn carts await us. The road is lost, invisible under the water; the animals walk bathed up to the belly in the middle of a veritable forest of shrubs and bushes. The bumps are insane, we pitch and roll, having the feeling we are still on a boat. We even climb stairs before arriving and nothing breaks down.’]

- The symbolism of Cambodian Water Festival: ‘Le génie du Mékong qui commande à ses eaux de né plus remonter vers le Grand Lac et de redescendre fertiliser le delta a bien voulu nous attendre à Pnom-Penh pour cette cérémonie. Les flots sont retenus, paraît-il, par une simple corde, un fil invisible que le roi du Cambodge doit couper d’un geste pour permettre aux eaux de redescendre vers la mer. La Fête des Eaux est ordinairement fixée au 21 novembre, et elle dure trois jours; mais cette année, à cause du voyage du gouverneur général, elle est avancée d’un mois. Il n’importe que les eaux aient déjà commencé de redescendre, elles né descendront pour les Cambodgiens que lorsque le roi aura coupé le fil.’ (p 32) [‘The spirit of the Mekong, who commands its waters not to rise again towards the Great Lake and to come back down to fertilize the delta, kindly waited for us in Pnom-Penh for this ceremony. The waves are held back, it seems, by a simple rope, an invisible thread that the king of Cambodia must cut with a gesture to allow the waters to descend towards the sea. The Water Festival is usually fixed for November 21, and it lasts three days; but this year, because of the Governor General’s trip, it is brought forward by one month. It does not matter that the waters have already started to fall, they will not descend for the Cambodians until the king has cut the thread.’]

- Khmer legacy in Laos: ‘Le village de Ban-Tât, à 14 kilomètres de Savan-Nakek, possède un tât presque intact. Il est creux à l’intérieur, revêtu de ciment et d’ornementations sculptées. On est disposé à y reconnaître une vaste cheminée à brûler les corps, remontant à l’époque khmer. Je suis la première à le photographier, me dit-on. Il remonterait au temps du roi Kounborom (chef d’un petit royaume du coté de Dien-Bien-Phu), dont parle une légende conservée dans les annales de Luang-Prabang. Ce roi avait sept fils. Son territoire étant insuffisant pour un si grand nombre d’héritiers, il les invita à se disperser et à descendre vers le sud, après leur avoir adressé de très beaux commandements. L’un fonda le royaume de Luang-Prabang; un autre descendit jusqu’à la mer; un troisième trouva les rapides du Mékong, apprit à y naviguer, et fonda le royaume de Vien-Tian; un quatrième vint dans le Song-Kon et y fit construire ce tât.’ (pp 272 – 73) [”The village of Ban-Tât, 14 kilometers from Savan-Nakek, has an almost intact tât. It is hollow inside, clad in cement and carved ornamentation. We are willing to recognize a vast fireplace to burn bodies, dating back to the Khmer period. I am the first to photograph it, I am told. It dates back to the time of King Kounborom (head of a small kingdom not far from Dien-Bien-Phu), of which a legend is mentioned in the Annals of Luang-Prabang. This king had seven sons. His territory being too small for such numerous heirs, he invited them to disperse and descend towards the south, after having addressed them with very admirable commandments. One founded the kingdom of Luang-Prabang; another went down to the sea; a third found the rapids of the Mekong, learned to navigate there, and founded the kingdom of Vien-Tian; a fourth came to Song-Kon and had this tarmac built there.’]

- Polygamy as an obstacle to Catholic conversion in 19th century Cambodia: ‘Il y a beaucoup de catholiques parmi les Annamites de Cochinchine; par contre les Cambodgiens sont plus difficiles à convertir et la polygamie nécessitée par une de leurs coutumes ajoute particulièrement à la difficulté. Les femmes ont l’habitude d’allaiter leurs enfants pendant trois ans, et pendant ce temps les maris exigent des suppléantes. Vainement on a pu décider quelques femmes à sevrer leurs enfants au bout d’un an, par mauvaise hygiène ou sevrage trop brusque les enfants sont morts.’ (p 15) [There are many Catholics among the Annamites of Cochinchina; on the other hand the Cambodians are more difficult to convert and polygamy, required by one of their customs, adds particularly to the difficulty. Women are in the habit of breastfeeding their children for three years, and during this time husbands demand substitutes. In vain have some women been convinced to wean their children at the end of one year, since due to bad hygiene or too abrupt weaning these children died.’]

- The Royal Ballet dancers as seen by a European woman: ‘Ce sont les mêmes danses qu’au Siam; les costumes des danseuses, de la plus grande richesse, étincellent de pierres précieuses. Scènes du Ramayana, filles du ciel et génies, scènes d’amour et d’enlèvement. Ces femmes, d’une souplesse, d’une grâce féline extrêmes, sont presque toutes jolies, très fines, très menues. Celles qui remplissent les rôles d’hommes sont assez grandes. Toutes doivent se maintenir longtemps en des poses qui doivent être fatigantes à l’extrême. Tantôt lents, tantôt précipités, les mouvements ont un moelleux charmant et jusqu’à des souplesses qui évoqueraient, s’il s’agissait d’Européennes, la pensée des désarticulations enfantines. Les torsions des mains et des doigts sont étrangement originales, et particulièrement les lais, les salutations, s’exécutent avec une harmonie exquise.’ (p 33) [‘These are the same dances as in Siam; the costumes of the dancers, of the greatest richness, sparkle with precious stones. Scenes from the Ramayana, daughters of heaven and geniuses, scenes of love and kidnapping. These women, of extreme flexibility and feline grace, are almost all pretty, very thin, very petite. Those who fill the roles of men are quite tall. All must be maintained for a long time in poses which must be extremely tiring. Sometimes slow, sometimes rushed, the movements have a charming softness and even suppleness which would evoke, if they were Europeans, the thought of childish contortions. The twists of the hands and fingers are strangely original, and especially the lais, the greetings, are performed with exquisite harmony.’]

- The high standing of the King’s female cook: ‘Autre visite importante chez haute et puissante dame, la cuisinière du roi [Norodom], que personne né dédaigne, et qui habite tout près de notre hôtel. Le souverain né mange avec sécurité que les aliments préparés par elle, et que l’on vient chercher avec elle dans les carrosses royaux. Sa Majesté prend plaisir quelquefois à lui rendre visite et elle lui prépare de petites fêtes à son gré. Elle lui a jadis sauvé la vie dans un incendie et lui est toute dévouée. Elle se tient assise à terre, très agitée, très remuante; une courte écharpe jaune appuyée sur un sein passé derrière le dos et retombe en avant par-dessus l’épaule. Le sampot à peine noué autour du corps formant jupe, à la manière des femmes, laisse la moitié du ventre à nu. A chaque instant elle rattache sampot et écharpe, qui né s’échappent jamais malgré la multiplicité et la rapidité de ses gestes. C’est aussi le costume des femmes qui sont près d’elle, avec de jolis enfants à peu près nus.’ (p 19) [‘Another important visit to a high-ranked and powerful lady, the king’s cook [Norodom], whom no one dares disdain, and who lives very close to our hotel. The sovereign safely eats only the food prepared by her, collected and brought to the Palace with her in royal coaches. His Majesty sometimes takes pleasure in visiting her, and she prepares small parties for him as he pleases. She once saved his life in a fire and is deeply devoted to him. She is sitting on the floor, very agitated and restless; a short yellow scarf resting on one breast passes behind the back and falls forward over the shoulder. The sampot barely tied around the body forming a skirt, like women wear it, leaves half of the stomach bare. At every moment she reattaches sampot and scarf, which never escape despite the multiplicity and velocity of her gestures. It is also the costume of the women who are near her, with pretty, almost naked children.’]

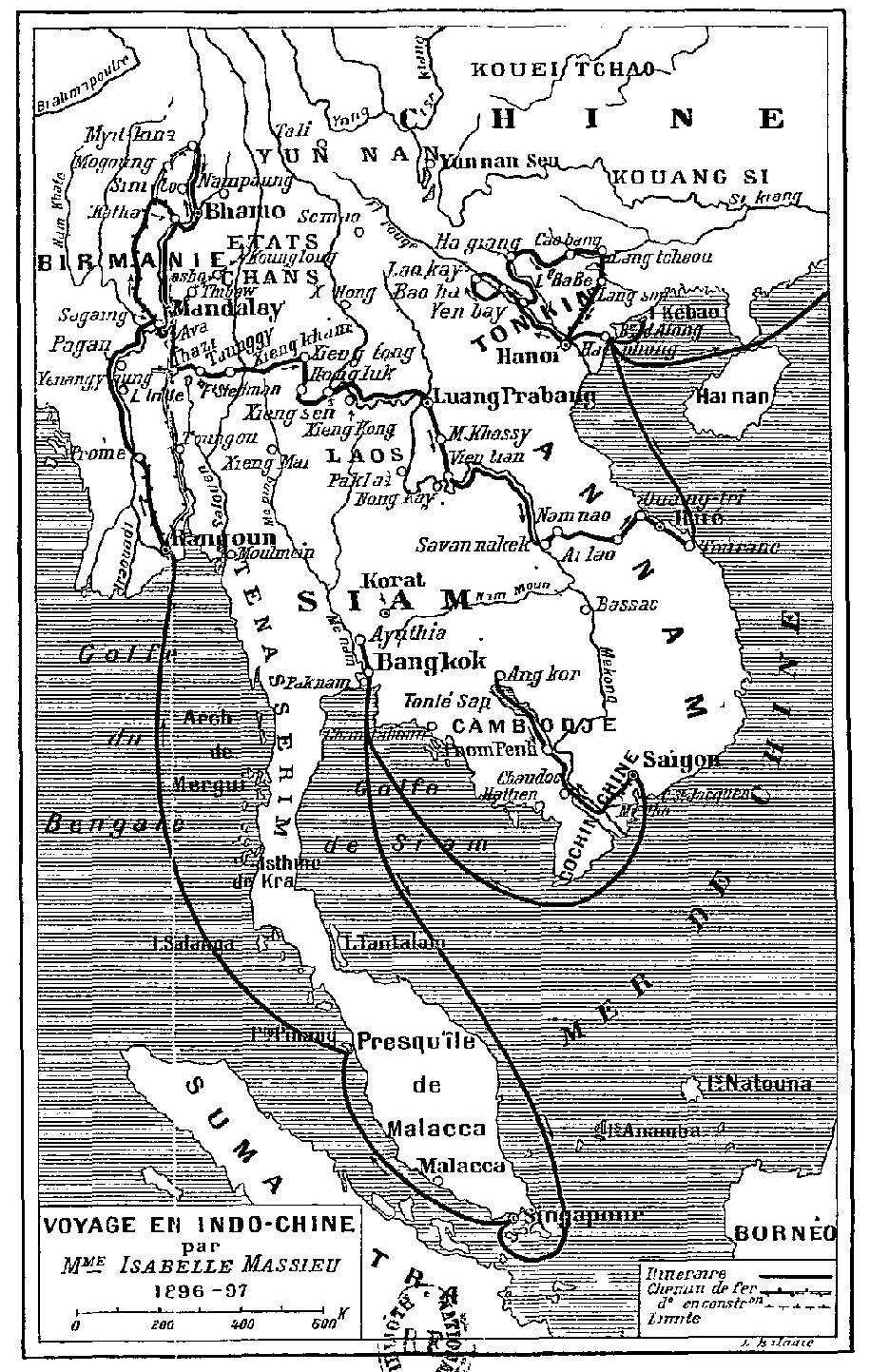

Isabelle Massieu’s Itinerary in 1896 – 1897

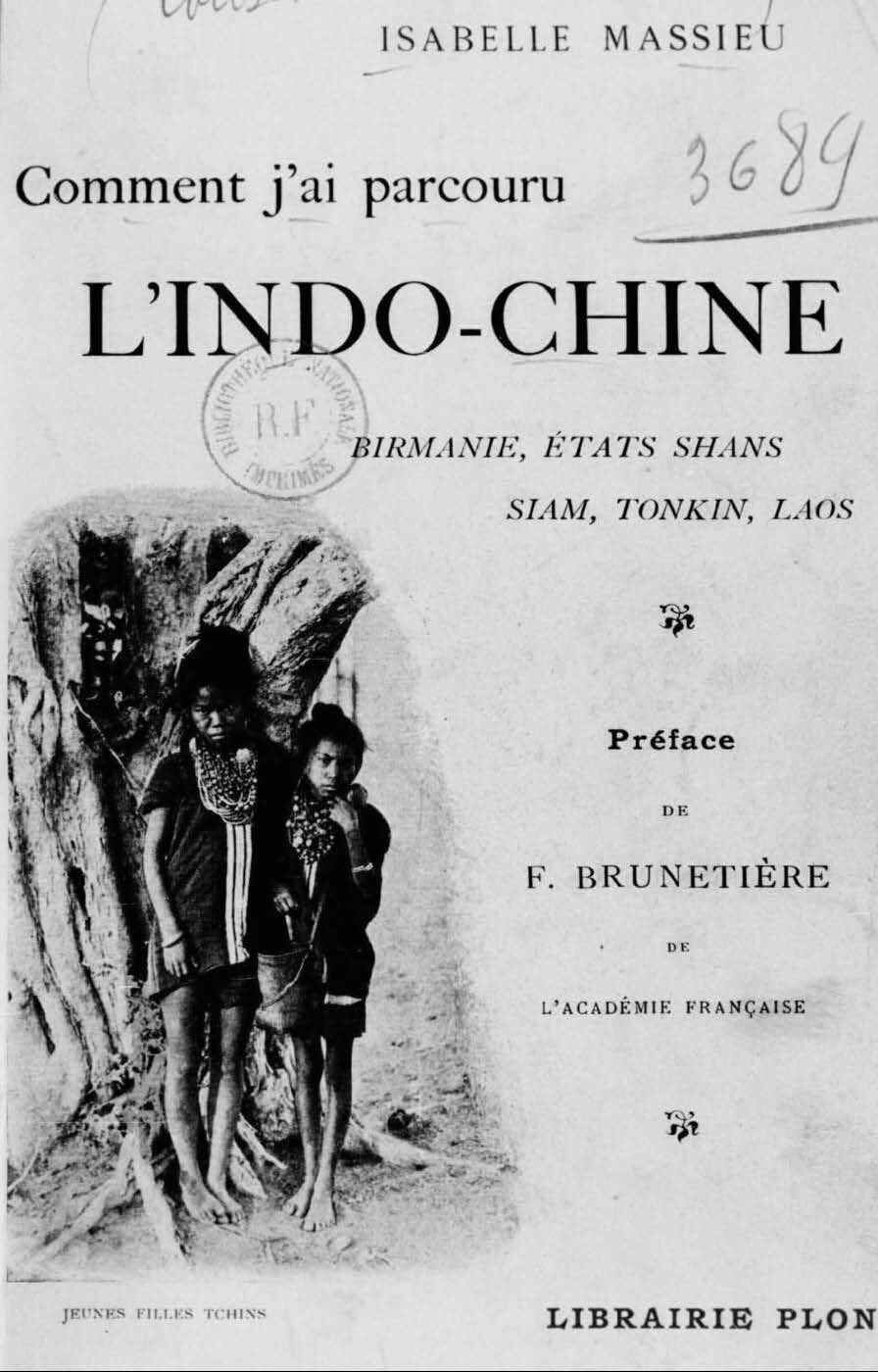

A drawing by Colonel Lyautey and one of the author’s photographs in the book

Tags: French explorers, women travelers, women, Modern Cambodia, Burma, Tonkin, Cochinchina, Siam, Lao, Cambodian cuisine, Tonle Sap, dance, dancers

About the Author

Isabelle Massieu

Isabelle Massieu (born Bauche, 3 Apr. 1844, Paris — 7 Oct. 1932, Paris-Suresnes) was a French traveler, writer and photographer, who was one of the first Western women to visit and write about Angkor (in 1896), the first French woman to travel to Nepal and Laos, and an outstanding observer of Asian cultures at the turn of the century.

She first traveled around Europe and the the Middle East with her husband, lawyer Jacques Alexandre Octave Massieu (1835−1891), then led solo travels when she was widowed at age 50 across India, China, Siam, French Indo-China (including the military zones of Haut-Tonkin) and British-ruled Burma. According to her conference to the Société normande de géographie in 1898, she was asked by the French Ministry of Public Education to develop a comparative study of English and French colonial administrations and methods.

In spite of the common misogyny in European academic and mass-media circles (see an example), her travel relations and photographs were recognized as important contributions to the knowledge of Asia at her time. Her visit to Cambodia (a pleasure travel as her ambition was to reach the Upper Mekong Valley) was organized with the help of Colonel Lyautey and Gouverneur-Général Rousseau. She was also close to the Catholic writer Paul Claudel, then French ambassador to Japan.

Antoine Brébion, a specialist in Southeast Asian biographies, wrote that Isabelle Massieu ‘se dirigea vers Ceylan en 1895 et s’enfonça dans l’Inde anglaise, mais la guerre du Tchitral l’obligea à se rabattre sur le Cachemire et le Ladak. De Peschawar, elle remonta à Srinagar et à Leh, visitant les lamasseries tibétaines, elle atteignit le lac Pangong à la frontière chinoise. En 1896 – 1897 elle visita la Cochinchine, le Cambodge, parcourut le Siam, la Birmanie et se rendit aux Etats Shans du Laos. De Luang-Prabang elle gagna Vien-Tian, descendit le Mékhong jusqu ‘à Savannakhet et se rendit à Hué par la brèche de Aï-Lao, puis elle parcourut le Tonkin de Laokai à Lang-Tchéou, d’où elle se rendit à Canton, puis à Shanghaï. De cette ville elle parvient au Yang-Tsé qu’elle remonta jusqu’à I‑tchang. Elle fit une courte apparition parmi les Aïnos de Sakhaline, visita les ports de la Corée et, parvenue à Pékin, traversa en charrette chinoise le désert de Gobi et poursuivit sa route par le Baïkal, Irkoustk, Tomsk et Omsk. Elle évita la voie ferrée du Transibérien et franchit 3.000 verstes pour gagner Samarcande et rentrer par le Caucase à Moscou. Douée de grandes qualités et de volonté, elle accomplit ce long voyage escortée d’un seul domestique, choisissant de préférence les chemins non frayés. Elle avait été chargée d’une mission par le Ministre de l’Instruction publique.’ (Dictionnaire…, p 257) [‘She headed to Ceylon in 1895 and entered English India, but the war in Chitral forced her to fall back on Kashmir and Ladak. From Peschawar, she went up to Srinagar and Leh, visiting the Tibetan lamasseries, and reached Lake Pangong at the Chinese border. In 1896 – 1897 she visited Cochinchina, Cambodia, traveled through Siam, Burma and went to the Shan States of Laos. From Luang-Prabang she reached Vien-Tian, went down the Mekhong to Savannakhet and went to Hue through the gap of Aï-Lao, then she traveled the Tonkin from Laokai to Lang-Tchéou, from where she went to Canton, then to Shanghai. From this city she reaches the Yang-Tse River, going upriver to I‑tchang. She made a brief appearance among the Ainos of Sakhalin, visited the ports of Korea and, having reached Beijing, crossed the Gobi Desert in a Chinese cart and continued on her way through Baikal, Irkustk, Tomsk and Omsk. She avoided the Transiberian railway and crossed 3,000 versts to reach Samarkand and return via the Caucasus to Moscow. Gifted with great qualities and will, she accomplished this long journey escorted by a single servant, preferably choosing unpaved paths. She had been entrusted with a mission by the Minister of Public Education.’]

The Paris Musée de l’Homme holds five volumes from Isabelle Massieu’s photographic Collection, some 600 photos including her own photographic work and prints she collected during thirty years about India, Tibet, China, Indochina, from amateur photographers or illustrious ones (Skeen & C°, G. R. Lambert, Nicolas & C°, W. & P., Wiele & Klein, Lala Deen Dayal, Mohan Lall, Bourne & Shepherd…).