Francis Garnier, sa vie, ses voyages, son oeuvre (Francis Garnier, Life, Travels and Work)

by Edouard Petit

A portrait of one of the most controversial members of the Mekong Expedition, and a plea for 'enlightened colonialism' in Indochina.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- M. Dreyfous & M. Dalsace, Paris

- Edition

- Digital version Gallica BNF (gallica.bnf.fr)

- Published

- 1894

- Author

- Edouard Petit

- Pages

- 288

- Language

- French

When does exploration stops, when does colonization starts? In this deliberately partial — the author was personally acquainted with Garnier´s relatives and with Joseph Perre, engineer in Avignon and Garnier´s friend from childhood — portrait, Edouard Petit attempts to attempts the aspirations, ideals and ambitions of a generation of French naval officers who took an important part in the rediscovery of Angkor, and in the colonization process of Indochina.

“La géographie française a enfin renoncé au platonisme” (French geographical studies have finally given up with platonism [abstractions]”), states the author in his preamble; for Garnier, “il né s’agit de rien moins que de chasser l’Angleterre de ses colonies et que de lui arracher l’empire des mers. Puis la vie coutumière le rappelle Garnier à la réalité ; ses idées se précisent; elles s’appliquent à l’organisation de la Cochinchine, à la prospérité de la ville qu’il administre, Cholon.” (‘the case is nothing less than to expel England from her colonies, to wrest the Empire of the Seas from her. Then daily routine brings him back to reality, to the organization of Cochinchina, to ensure prosperity to the city under his administration, Cholon”) [The Chinese trading post 4 km off Saigon]

Another author, Georges Taboulet, has described in 1970 the push for the colonization and the control of the Mekong River from idealistic young French officers: “S’il y eut des ‘groupes de pression’, ce n’est pas dans les postes diplomatiques d’Extrême-Orient et encore moins en France qu’il convient de les chercher mais à Saigon, et plus spécialement dans le « bazar » de Cholon, où, le soir, se réunissaient, aux côtés de Francis Garnier, féru du Mékong, une élite de jeunes officiers de marine, animés d’une foi ardente dans les destinées d’une vaste Indochine française, susceptible de relayer à un siècle de distance, les grandes Indes de Dupleix.” (“If there ever were ‘lobbies’, they are to be found not within the Far East diplomatic missions, and even less in France, but in Saigon, and more precisely in the ‘Cholon Bazaar’ where, evening after evening, an elite of young Navy officers gathered, passionately believing in the prospect of a vast French Indochina, a possible transposition of the Grand Indies invoked by Dupleix one century earlier.”)

The hostility towards England, then consolidating its influence in SIam and Burma,is the main motivation the author sees in Garnier (and other members of the Mission d’exploration du Mékong): “L’idée qui le tient et qui le travaille, c’est d’abattre le drapeau britannique dans toutes les colonies où il flotte (…) Il né parle de rien moins que d’armer en course comme les corsaires ; il voudrait imiter les exploits de Jean-Bart et de Surcouf. Plus tard, quand les années eurent apaisé ses premières ardeurs, quand il eut vu par quelles causes, par quel labeur acharné, par quelle merveilleuse persévérance, l’Angleterre avait conquis et agrandi son domaine colonial, il passera de la colère et de la haine au respect, presque’à l’admiration.”

After mentioning that French attempts to colonize the Mekong Delta dated back from Louis XVI, the author expresses the typical colonial prejudices of the era regarding Cambodia and its people: “Le Cambodge était pressé entre ses deux puissants voisins, à l’ouest, Siam, à l’est, l’Annam. Nul né songeait encore à faire prévaloir l’influence française chez les descendants dégénérés des Khmers, chez les Cambodgiens indolents et mous, ou chez leurs esclaves les Penings et les Kouïs, que la servitude a hébétés et qui sont actuellement incapables de compter jusqu’à cinq. Qui aurait, en 1801, même au lendemain de l’expédition de Chine, rêvé qu’un jour les riverains du Mékong verraient flotter sur leur huttes le drapeau français, signe d’alliance et de protection?”

As for the quest for the Mekong River springs, high in the Tibetan mountains, the author notes: “L’origine tibétaine des fleuves indo-chinois est elle révélée à la science? Non certes. Malgré les tentatives de M. Pryevalsky (1) qui de 1876 à 1880 s’élève par la Chine septentrionale jusqu’aux sources du Hang-Ho; malgré les efforts de M. et M. de Uyfalvy (2) qui, à la fin de l’année 1881, par l’Asie centrale pénètrent aux pays du Cachemire et en rapportent de riches collections, le problème n’est pas résolu, il reste tout entier, tel que l’a posé Francis Garnier.” (‘Has the Tibetan origin of the Indochinese rivers been scientifically proved? Not at all. In spite of Mr. Pryevalsky’s (1) attempts, who from 1876 to 1880 would climb from Northern China up to the Hang-Ho Springs; in spite of Mrs. and Mr. de Uyfalvy’s (2) efforts when, at the end of 1881, they reached the Kashmir lands and brought back rich collections, the problem remains unsolved, entirely as Francis Garnier formulated it.”)

(1) N.M. Prejvalsky.

(2) Marie and Charles de Ujfalvy.

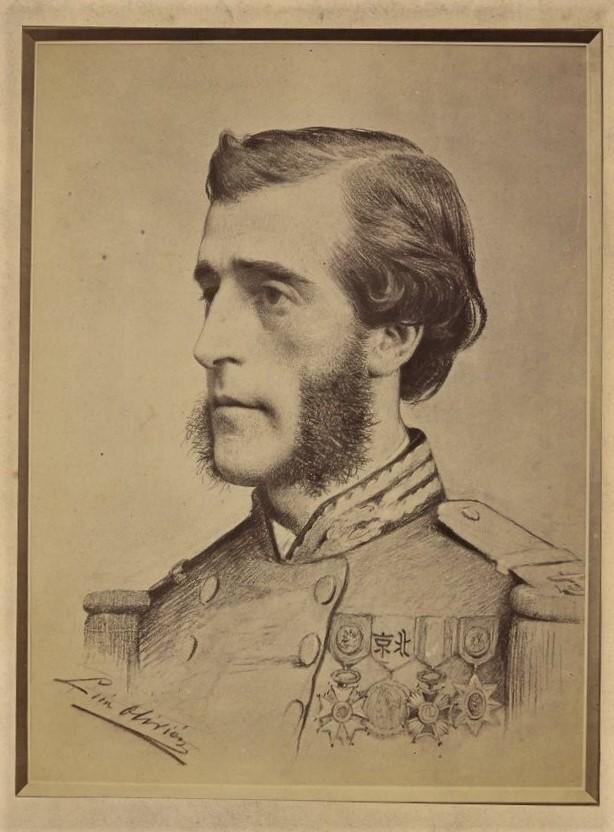

A portrait of Francis Garnier (source: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

Angkor Database input:

- Rivalry between British and French colonial expansion have been observed on site by American envoys and merchants. According to

W.S.W. Ruschenberger, a naval doctor with the first American ‘East India Squadron’ in 1836, under the command of Commodore E.P. Kennedy, ‘the English have made several unsuccessful attempts to effect a treaty with Cochin-China, and attribute their failure to the misrepresentations of the French and Portuguese, in regard to the British character. But there are other obstacles found in the low estimation at which merchants are held by the Cochin-Chinese, and the frequent civil and foreign wars by which the government has been distracted for ages. At present they are contending with the Siamese for the territory of Cambodia, which, it seems, they have long been desirous of annexing to their own.” In August 1884, John S. Mosby, the US Consul in Hong Kong, argued: “recent events … have practically reduced the whole of Tonquin and the Kingdom of Cambodia to the condition of a French province .… American vessels frequently go there [Saigon], and many more will probably visit the place in the future than formerly. There is no doubt that the Commerce of Saigon will be largely increased as the interior of the country is developed by Europeans.’ (source: Robert Hopkins Miller, The United States and Vietnam 1787 – 1841, Washington: 1990) - ‘De Pnom-Penh, le 5 avril 1866, Doudart de Lagrée, de retour des « belles ruines d’Angkor », rend compte à l’amiral [French Governor La Grandiere] qu’il a rencontré des Anglais qui l’ont interrogé sur le but de l’exploration, connu à Bangkok depuis quelques mois déjà. Doudart fait observer que, de Bangkok jusqu’au Yunnan, il y a un mois de marche en moins que de Saigon au Yunnan; si l’entreprise n’est pas menée plus rondement, il est à craindre que « les Anglais né nous préviennent aussi (comme à Angkor) dans le haut du fleuve ».’(‘From Phnom Penh on April 5, 1866, Doudart de Lagrée, back from “beautiful ruins of Angkor”, reports to the Admiral [French Governor La Grandiere] that he has met some Englishmen who asked him about the purpose of the expedition, already known in Bangkok for a few months. Doudart remarks that, from Bangkok to Yunnan, the travel is one month shorter than from Saigon; would the mission not expedited more diligently, it must be feared that “the English will again (like in Angkor) beat us to the upper River.”) (source: G. Taboulet, see above). The ‘Englishmen’ were Scottish photographer John Thomson and his interpreter, H.G. Kennedy.

- Read Edouard Petit’s book, Le Tong-Kin (1887, E. Leroux, Paris)

Tags: French explorers, colonization, colonialism, cartography, Portuguese missionaries, British influences, British explorers, Yunnan, Mekong River, Mekong Mission

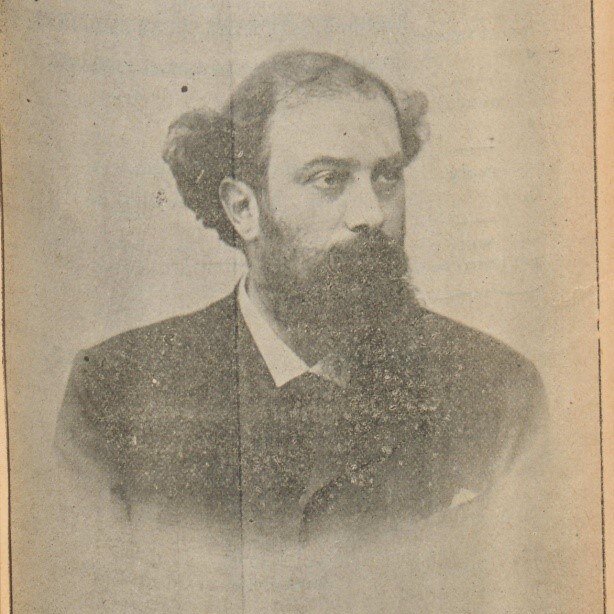

About the Author

Edouard Petit

Educationist, historian and sociologist Edouard Petit (17 March 1858, Marseille — 19 Feb. 1917, Perpignan, France) was an Inspector-General of French Public Education, a professor and an essayist who promoted the ‘civilizing mission’ of French colonialist endeavor.

After presenting a doctorate thesis on Andrea (André) Doria, a 16th century Italian Navy officer whom Petit dubbed ‘the admiral-condottiere’, Edouard Petit pursued his passion for marine history and geography while leading a career as a teacher (at Lycée Jeanson de Sailly, Paris) civil servant, and radical-Republican (and freemason from 1905) politician. He published books about Tonkin, biographies of Sully, Etienne Marcel, Francois Dupleix and Francis Garnier, as well as an ambitious Histoire Universelle Illustrée des Pays et des Peuples (Illustrated History of Countries and People).

His bibliography has often been confused with the one of writer and colonial administrator Edouard Théophile Georges Petit.

The other Edouard Petit

French Colonial Administration public servant Edouard Théophile Georges Petit (15 March 1856, St Denis de la Réunion — 14 March 1904, at sea, death registered in Perth, Australia) authored numerous travels books – under his name, or the pseudonym Aylic Marin – about Oceania, Tonkin, South America.

During his visit to French Polynesia, he befriended French painter Paul Gauguin and writer Victor Segalen. He served as Governor-General of the French establishments in Oceania.

Interestingly, ‘Aylic’ was the first name of his father-in-law, Aylic Langlois, a dramaturgist and civil administrator, father of his spouse Alix-Marie-Georgina Langlois dite Langle (1860−1930).