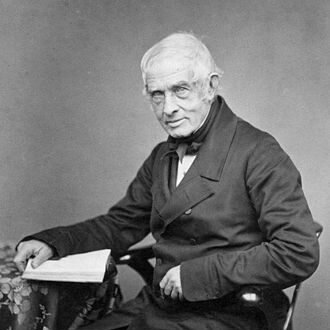

A Scottish surgeon, colonial administrator, diplomat, and author who served as the second and last Resident of Singapore, Dr John Crawfurd (13 Aug 1783, Islay, Scotland – 11 May 1868, London, UK) visited Siam and Cochinchina in 1821 – 1822, during a diplomatic mission commandited by the Governor-General of Bengal, Lord Hastings.

Crawfurd, who had served in India and Java before the travel, sailed from Calcutta on 21 Nov 1821, went through Penang and Quedah, and was received — quite reluctantly — by King Rama II before sailing to Hué with Captain Dangerfield, a military escort led by Lt Rutherford, and his wife, Horatia Ann Perry-Crawfurd. When he reached Saigon, however, the King of Cochinchina Minh Mang refused to grant him an audience. However, he was able to meet with the Chief of Lao tribes Choa Añu, a first diplomatic contact for United Kingdom while the French were already active in the area.

In Bangkok, the objet of his mission was

to renew commercial intercourse and to remove the obstacles to free trade which existed in these two countries. However, as British possessions in the East were expanding at the time, and as the troubles between the British East India Company and Burma were beginning to sharpen, Crawfurd’s first endeavor in Siam, as instructed by his government, was to “remove every unfavourable impression which may exist as to views, or principles, of the Honourable Company and the British nation….” Crawfurd was further instructed specifically to “refrain from demanding or hinting at any of those adventitious aids or privileges…such as… exemption from municipal jurisdiction and customary imports….The choice of Crawfurd was based upon his acquaintance with the peoples of the Eastern Archipelago. […] The negotiations between Crawfurd and Siam’s representative, Phra Klang,5 began on April 16, English language being unknown to the Siamese, the negotiations had to be conducted in four languages, and in a roundabout way, i.e., from Siamese to Malayan, from Malayan to Portuguese, and then from Portuguese to English. Upon Crawfurd’s request for a substitution of one simple form of duty for the existing various imposts upon commerce, Phra Klang desired in return a specific engagement that not less than four British ships should come yearly to Bangkok. Crawfurd could not make such a commitment. Phra Klang’s reservation was made obviously with a view to a compensation for the loss in revenue that the new system of one duty would incur should it be established. Two years earlier, a commercial treaty had been made with the Portuguese whereby the Siamese government agreed to reduce the rate of import dues and consented to having a Portuguese consul reside at Bangkok. But since then, not a single Portuguese ship had come. The Siamese government was dismayed that it should have made a treaty about nothing. Despite specific instructions to the contrary, Crawfurd raised the question of an appointment of a resident British agent and hinted at the needs for a special arrangement for the security of the persons and properties of British subjects. These were flatly denied by Phra Klang, who pointed out the unfavorable precedent set by the Portuguese. He distinctly stated that his government would make no alteration in the established laws of the country in favor of “strangers.” [see Owart Suthiwartnarueput, From Extraterritoriality to Equality: Thailand Foreign Relations 1855 — 1939, Bangkok, International Studies Center, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2021, 368 p., ISBN 978 – 616-341 – 099‑3.]

In 1830, he related this mission in his Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China, exhibiting a view of the actual State of these Kingdoms (London, 2 vols). He is also the author of an History of the Indian Archipelago, and of Origins of the Gipsies.