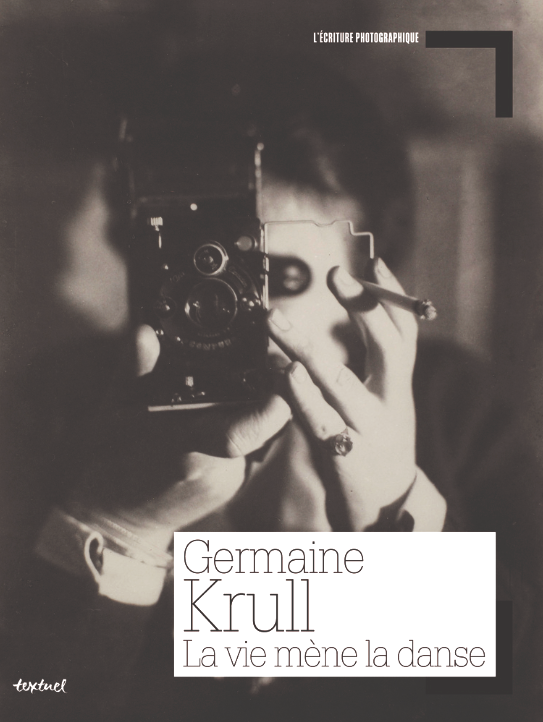

La vie mène la danse [Germaine Krull's Posthumous Autobiography]

by Germaine Krull & Françoise Denoyelle

The fascinating life of a talented photographer and a strong-willed woman spanning the whole 20th century and several continents.

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- L'écriture photographique, Textuel, 2015 & 2019

- Edition

- 2019 edition [out of print]

- Published

- 2015

- Pages

- 445

- ISBN

- 978-2-84597-522-4

- Language

- French

No big words in this recollection of German Krull’s adventures, political struggles, artistic creations, but vivid descriptions of places, people and events by a fiercely independent observer and activist. Following her instincts (and not always her best judgement, as she easily admits it), the avant-garde photographer who was at home in the most groundbreaking artistic circles, who gained Charles De Gaulle’s admiration with her committment to the anti-fascist cause, left many ‘tapuscrits’ (typescripts now kept at the remarkable Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany), here collated, edited and annotated by photography historian Francoise Denoyelle.

We were particularly taken by the following remarks and notations:

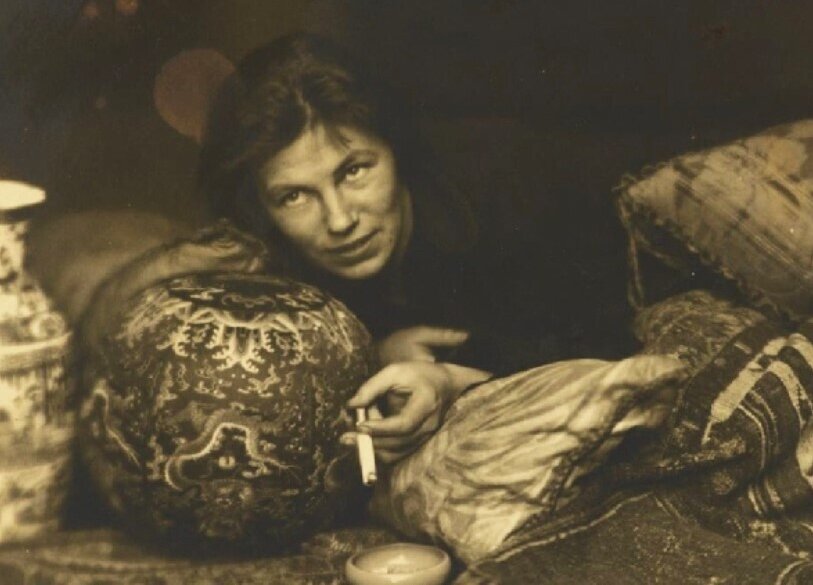

Mad Dog and Photography

In 1915, GK enlisted to the Munich School of Photography, where her female friends nicknamed her ‘Zottel’ [ Shock of Hair in German], which became ‘Chien Fou’ (Mad Dog) in French, because of her vigorous mane of hair. It’s when she started to develop her talent, and to embrace left-wing activism. In a conversation with editor Denoyelle, she was to assert: “Ni les hommes, ni les pays, ni les conventions né m’ont fait dévier de mon chemin, dans la vie comme en photographie.” [“Neither men, nor countries, nor social conventions have made me change course from my path, in life as in photography.”]

Later on in Amsterdam and Paris, with her long-lasting lover Eli Lotar — and she also married writer and film director Joris Ivens to get her Dutch passport –, she explored commercial and press photography, reaching consecration in 1928 with her first published portfolio, Fers, which was to became ‘Krull-Metal’. Louis Jouver, René Char, Man Ray, Colette, René Clair, the Delaunays, Pierre Mac Orlan, Man Ray, the list of acquaintances and friends is a Who’s Who of the literati of her time.

Men

Apart from Else — the only woman who inspired me more than friendly feelings, but she was married and had a lover, so it didn’t leave anything substantial for me” –, Germaine was both a tomboy and a passionate woman who ”

In Rio, where she was actively promoting the French Resistance, she falls for head over heels for…an Italian fascist, the physicist Giuseppe Occhialini, “beau comme un jeune Napoléon, agressif et violent” [“as handsome as a young Napoleon, and a fierce badass”]. Brief but intense encounter, during which she convinces him to climb the hill “to see from closer the Christ, who appeared to be much more beautiful from afar.”

Later, while living in Bangkok: “Il y a toujours eu cette espece d’hommes dans ma vie, foncièremerent mauvais et nuls mais avec une sorte de pouvoir sur moi. Peter était l’un d’eux. Je me suis amourachée en sachant parfaitement que c’était un idiot, mais je n’y pouvais rien. Il avait tout du gigolo un peu abimé, en plus. je pense, pédéraste. Il était bon danseur et plein de gaieté. Je dansais toute la nuit avec lui.” [“There was always this kind of men in my life, fundamentally bad and useless but with some sort of power over me. Peter was one of them. I fell in love knowing full well he was an idiot, but I couldn’t help it. He had all the characteristics of a gigolo, a little damaged, and in addition, I think, pederast. He was a good dancer and full of cheerfulness. I danced all night with him.”]

Thai Buddhist Art

“Il me restait beaucoup de temps pour comprendre l’art siamois. Les bouddhas, voila ce qu’il y avait de pur. Les époques étaient assez différentes et les bouddhas variaient selon chacune. Les plus beaux, d’apres moi, étaient les véritables U Tong du XIVeme ou XVeme siecle. Il en reste tres peu. Les Thais pensent que la grande époque des bouddhas est celle de Sukhothai, ce sont les plus recherchés. À l’epoque où j’étais au Siam, les bouddhas n’étaient ni vendus ni achetés, on né les trouvait pas dans les magasins. Si un bouddha doit venir chez vous, disent les Thais, on vous le donne. La fabrication des bouddhas ‘anciens’ a commencé avec le tourisme.” [“I had a lot of time left to understand Siamese art. The Buddhas, that is what was pure. The times were quite different and the Buddhas varied according to each one. The most beautiful, in my opinion, were the real U Tong from the 14th or 15th centuries. There are very few left. The Thais hold that the great era of the Buddhas is that of Sukhothai, they are the most sought after. At the time when I was in Siam, the Buddhas did not were neither sold nor bought, they could not be found in the shops. If a Buddha must come to your house, say the Thais, it is given to you. The manufacturing of ‘old’ Buddhas began with tourism.”

Somewhere else in the book, she mentions the French diplomatic mission to Lopburi [“une française” in the text, “ambassade” is missing) under the reign of Louis XIV, at the instigation of Constantine Phaulkon (or Phaulcon), a Greek adventurer who became a kind of super minister to the Siamese king in Lopburi. [The Chevalier de Chaumont was the first French ambassador for King Louis XIV in Siam. He was accompanied on his mission by Abbé de Choisy, the Jesuit Guy Tachard, and Father Bénigne Vachet of the Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris. See the Voyage du Comte de Forbin a Siam for more details].

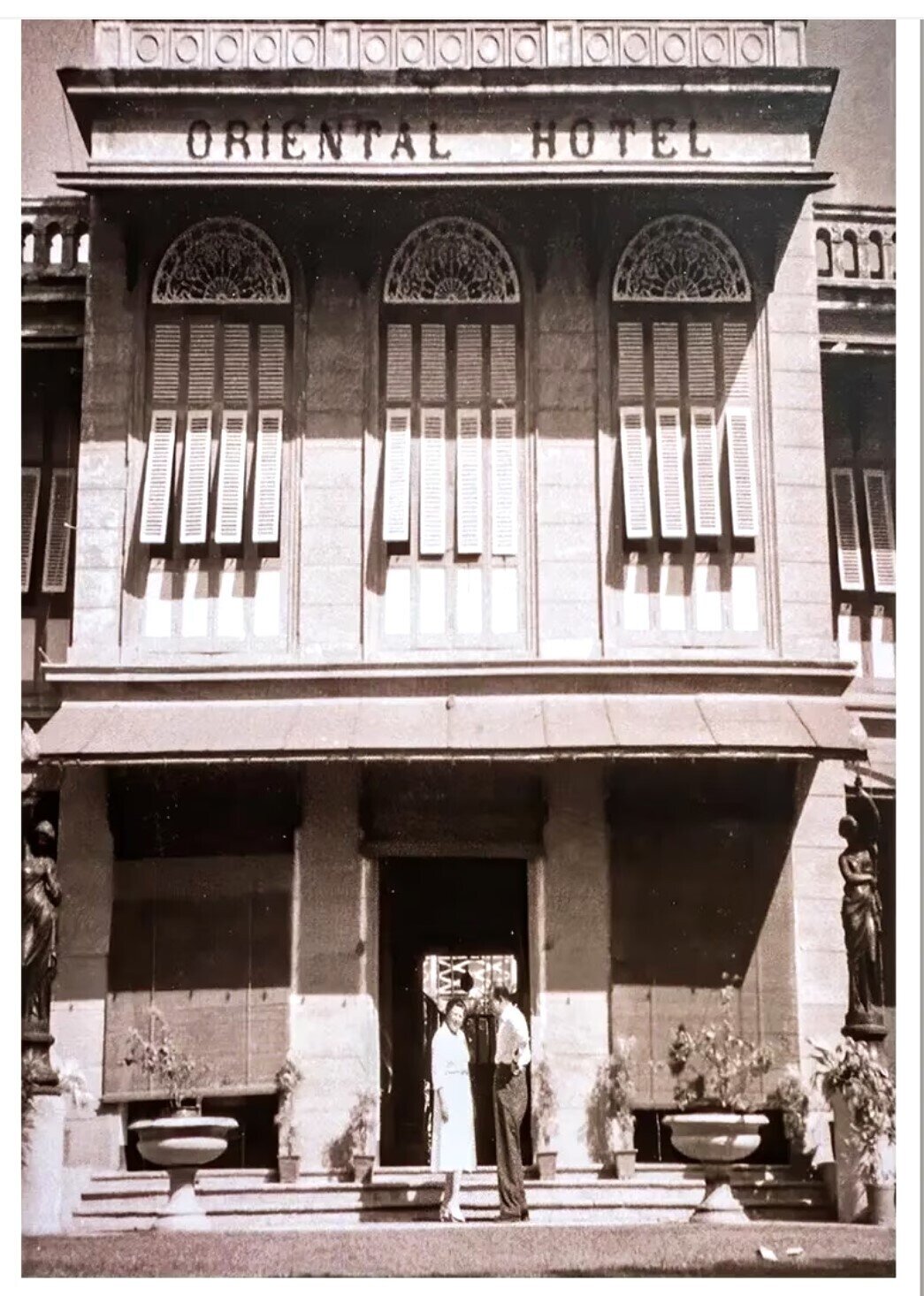

Jim Thompson & The Bamboo Bar Stint

While renovating the legendary Oriental Hotel in Bangkok and opened it on June 12, 1947, GK came to work with architect, interior and silk designer Jim Thompson, who became an associate. The clash between them happened around the essential redesign of the hotel: while Germaine wanted to “turn the building towards the river”, Jim insisted that it should be developed along the alley leading to the bank. “Les gens adoraient le fleuve, c’est là qu’il fallait bâtir” [“People loved the river, it was there that we should build”], she notes, and Jim Thompson left after a raucous row: “Il pouvait être d’une vulgarité inouie quand il était en colere.” [“He could be incredibly vulgar when he was angry”].

Then, Germaine came up with the idea of launching her own haunt within the hotel: “L’après-midi, je dormais dans ma maison tranquille. Le soir, Hiram, le chauffeur, venait me chercher pour le Bambou Bar. C’est la que je retrouvais des amis et que la vie devenait fascinante […] L’atmosphère du Bamboo Bar était assez pleine d’intrigues. Mais ce qui s’y faisait n’avait pas d’importance et n’en passait pas ses portes. Le Jour de l’an chinois était le seul jour férié de mes boys. Ce jour-là, il n’y avait aucun extra à l’Oriental. Le déjeuner était servi a une heure précise et ensuite les boys disparaissaient. Le soir, il y avait un immense dîner chinois dans la salle à manger. Les boys nous invitaient! Le repas était servi par tables de huit personnes et on avait généralement dix tables. C’était toujours très gai, on faisait des discours et on buvait sec. On était une grande famille, et je crois que cela tenait uniquement à moi.” [“In the afternoon, I napped in my quiet house. In the evening, Hiram, the driver, came to pick me up for the Bamboo Bar. That’s where I met friends and where life became fascinating […] The atmosphere of the Bamboo Bar was quite full of schemes and affairs, but what was going on there didn’t matter and didn’t pass its doors. […] Chinese New Year’s Day was the only public holiday in my There were no extras at the Oriental that day. Lunch was served at a specific time and then the boys disappeared. In the evening there was a huge Chinese dinner in the dining room. The boys invited us! The meal was served by tables of eight, and we usually had ten tables. It was always very cheerful, we made speeches and we drank a lot. We were a big family, and I think that was only due to me.”]

Tags: women, women artists, women travelers, World War II, photography, hotels, Bangkok

About the Author

Germaine Krull

Germaine Luise Krull (20 November 1897, Posen-Wilda (then in Germany, now Poznan, Poland) – 31 July 1985, Wetzlar, Germany) was an avant-garde photographer, political activist, and avid traveler who beautifully captured Khmer temples in the 1960s before settling for a while in Tibet in her ongoing search for spirituality and a better world.

A free-thinker who questioned the patriarcal order — with the approval of her own father — from a young age, she attended the the Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie, a photography school in Munich, with the influence of Frank Eugene’s teaching of pictorialism, and opened her own studio there in 1918, portraying prominent artists such as Kurt Eisner, Rainer Maria Rilke, Friedrich Pollock, and Max Horkheimer.

Inclined to communist activism, she was harceled by police in Germany and Austria, traveled to Bolshevik Russia in 1921 with lover Samuel Levit, was imprisoned and expelled from there. She moved to Berlin, — where she created a series of nude photos with a quite explicit lesbian message — Amsterdam — where she met filmmaker Joris Ivens, with whom she contracted later a marriage of convenience — and Paris, where her ‘modernist’ style was remarked by surrealist circles and where she befriended artists such as photographers Man Ray ans André Kertész, artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay, and writers Colette, André Gide, Jean Cocteau or André Malraux. In her much-acclaimed portfolio Métal (1928), a 64 black-and-white dramatic shots in which she captured metallic architectural structures, “the essentially masculine subject of the industrial landscape”, in particular the Eiffel Tower. It is there that she portrayed writer and traveler Titayna with her Buddha head.

Living in Monte-Carlo in 1935 – 1940, Germaine Krull kept contributing to major photo magazines, travel and fiction books. Fleeing collaborationist France, she escaped to Brazil, French Equatorial Africa, Algeria, and actively contributed to the Resistance, capturing military action in France in 1944 – 1945. Her proximity to Malraux — they were working on a book about the sculptural and architectural art of Southeast Asia that never materialized — led to her involvement with the Gaullist movement. In her autobiography, she reported that the last time she saw Malraux in Paris — more precisely at La Lanterne, Malraux’s residence in Versailles –, “j’ai laissé plus de 1500 photos chez André, et elles y sont toujours!” [I left more than 1,500 photos at André’s, and they’re still there!] [1]. She went to Southeast Asia, first Laos, then Thailand and Cambodia in 1946 as a war correspondent and a representative of the French Resistance, and was spotted as such by the American CIA, for instance in this confidential dispatch.

With famous designer Jim Thompson, she decided to remodel and refurbish the derelict Oriental Hotel in Bangkok — which was to become the Mandarin Oriental –, and in spite of many disagreements with Thompson remained its co-owner until 1966. She designed the now iconic Bamboo Bar, and slowly but surely led the hotel to grow from the Japanese Officers Club it had been turned into during World War II, and then to a transit hospitality center for anti-fascist activists, to a high-end establishment. [Read a complete and richly illustrated saga of the hotel by Wild’n’Free Diary.]

Meanwhile, she collaborated to three photo and text books about Thailand, and traveled frequentely to Angkor, photographying then lesser-known temples such as Pre Rup or Preah Khan. 268 of these remarkable documents are kept at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, within her archives donated by her heirs. Angkor Database wishes to make more accessible Krull’s unique contribution to the photographic documentation of Angkor Wat and other Khmer Temples.

Later on, Germaine Krull went briefly back to Paris, then moved to North India, where she embraced the Sakya teaching of Tibetan Buddhism. Her late work reflects her lifelong interest in Buddhist art and dance, both themes that had inspired her so profundly in Angkor. Her final major photographic publication was the 1968 book Tibetans in India, including a portrait of the Dalai Lama.

[1] Germaine Krull, La vie mene la danse, ed. Francoise Denoyelle, Textuel, Paris 2015 and 2019 [out of print], p 397. The editor added that she asked Madeleine Malraux (7 April 1914, Toulouse – 10 January 2014, Paris) about these photographs in 2001, but the pianist and concertist who had been Malraux’s companion from 1944 to 1966 said she had no idea of this collection’s whereabouts.

- Main publications: Métal, Paris: Librairie des arts décoratifs, 1928. (New facsimile edition published in 2003 by Ann and Jürgen Wilde, Köln.) | 100 x Paris, Berlin-Westend: Verlag der Reihe, 1929. | Études de Nu, Paris: Librairie des Arts Décoratifs, 1930. | with Raúl Lino and Ruy Ribeiro Couto, Uma Cidade Antiga do Brasil, Ouro Preto, Lisboa: Edições Atlântico, 1943.| Chiengmai, Bangkok: Assumption Printing Press, 1955. | with Dorothea Melchers, Bangkok: Siam’s City of Angels, London: R. Hale, 1964. | with Dorothea Melchers, Tales from Siam, London: R. Hale, 1966. | Tibetans in India, Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1968. | Posthumous autobiography: La Vita Conduce la Danza, Firenze: Filippo Giunti, 1992. ISBN 88−09−20219−8 (La vie mène la danse or “Life Leads the Dance”, translated into Italian by Giovanna Chiti.); La vie mène la danse (L’écriture photographique), ed. Francoise Denoyelle, Paris : Textuel editions, 2015. ISBN 978−2−84597−522−4.

- Among Germaine Krull’s contributions to literary work: Bucovich, Mario von, Paris, New York: Random House, 1930. | Colette. La Chatte, Paris: B. Grasset, 1930. | Nerval, Gérard de, and Germaine Krull, Le Valois, Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1930. | Claude Farrère, La Route Paris-Biarritz, Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1931. | Morand, Paul, and Germaine Krull, Route de Paris à la Méditerranée, Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1931. | Simenon, Georges, and Germaine Krull, La Folle d’Itteville, Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1931. | André Suarès, Marseille, Paris: Librairie Plon, 1935. | Vailland, Roger, La Bataille d’Alsace (Novembre-Décembre 1944), Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1945.

- Films: Six pour dix francs (France, 1930) | Il partit pour un long voyage (France, 1932)

- References: MacOrlan, Pierre, Germaine Krull: Photographes Nouveaux, Paris: Gallimard, 1931. | Rosenblum, Naomi, A History of Women Photographers, 2nd edition, New York: Abbeville Press, 2000. ISBN 0−7892−0658−7. | Baker, Kenneth. “Germaine Krull’s Radical Vision / Photographer’s Work Featured at SFMOMA”, San Francisco Chronicle, 15 April 2000. | “Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print 1919 – 1939”, Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1999. ISBN 84−8026−125−0. | Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn, Germaine Krull: Fotografien 1922 – 1966, Köln: Rheinland-Verlag, 1977. ISBN 3−7927−0364−5. | Bouqueret, Christian, and Moutashar, Michèle, Germaine Krull: Photographie 1924 – 1936, Arles: Musée Réattu, 1988. | Sichel, Kim, From Icon to Irony: German and American Industrial Photography, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995. ISBN 1−881450−06−6.; Germaine Krull: Photographer of Modernity, The MIT Press, 1999, ISBN 0−262−19401−5.; “Germaine Krull and L’Amitié Noire: World War II and French Colonialist Film”, in Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place, ed. Eleanor M. Hight and Gary D. Sampson, London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0−415−27495−8.; “Germaine Krull à Monte-Carlo [Germaine Krull: the Monte Carlo Years]”, Montréal: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, 2006, ISBN 2−89192−306−5. | Kosta, Barbara. “She was a Camera”, Women’s Review of Books, volume 17, issue 7, pages 9 – 10, April 2000. | Specker, Heidi, Bangkok — Heidi Specker Germaine Krull im Sprengel-Museum Hannover, 9. Oktober 2005 bis 25. Juni 2006. Zülpich: Albert-Renger-Patzsch-Archiv, 2005. ISBN 3−00−017658−6. | Bertolotti, Alessandro, Books of Nudes, New York: Abrams, 2007. ISBN 978−0−8109−9444−7. | Dumas, Marie Hélène. Lumières d’Exil, Paris: Gallimard and Éditions Joëlle Losfeld, 2009. ISBN 978−2−07−078770−8. (French novelization of Germaine Krull’s life.) | Roth, Andrew, ed., The Open Book: a History of the Photographic Book from 1878 to the Present, Göteborg, Sweden: Hasselblad Center, 2004. | “Portrait of Hedonist with Glasses Half Empty”, The Gazette (Montréal), 30 December 2006. | Frizot, Michel, Germaine Krull, Paris : Hazan editions, 2015. ISBN 978−2−7541−0816−4. (Catalog of “Germaine Krull (1897−1985)”, Jeu de Paume Museum Exhibition, 2015).

- Latest and Upcoming Exhibitions: “Germaine Krull– The Return Of An Avant-Gardist”, The Jim Thompson Art Centre & The Goethe Institute, Bangkok, June 2022. | “Germaine Krull and Southeast Asia”, Bangkok, September 2023.

About the Editor

Françoise Denoyelle

Françoise Denoyelle is a French historian, professor and photography curator. After her doctoral thesis in 1991 (Le marché et les usages de la photographie à Paris pendant l’entre-deux-guerres), she taught at the School of Photography Louis-Lumière, and coordinated the collective of photographers Le Bar Floréal Photographie.

Since 2004, she heads the Comité des donateurs et ayants droit de l’ex-patrimoine photographique [Donors and Beneficiaries Committee for Photographic Heritage] at the French Culture and Communication Ministry. Since 1998, she is the editor-in-chief of the online photography review Du sel au pixel, and is actively involved in the Paris Mois de la photo.

Among her publications: André Malraux, Portraits choisis par Françoise Denoyelle, Paris, 11 – 13 éditions, 2017, 99 p. (ISBN 979−10−91004−32−9); Arles, les Rencontres de la photographie : une histoire française, Paris, Art book magazine ; Arles : les Rencontres de la photographie, 2019, 256 p. (ISBN 978−2−8216−0128−4, BNF 46536083).

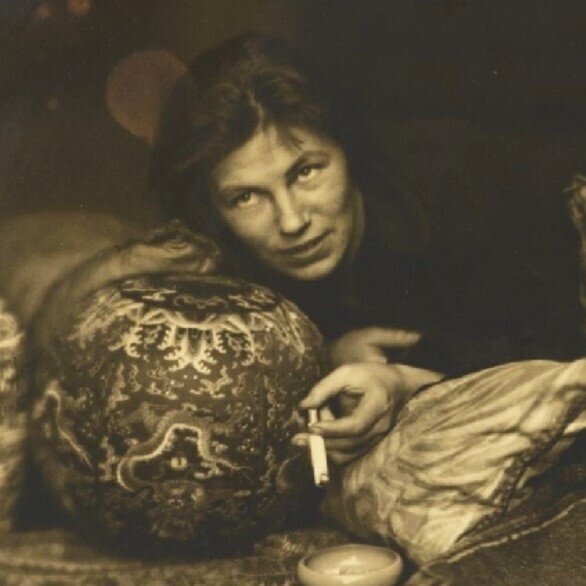

Photo ©Ava du Parc