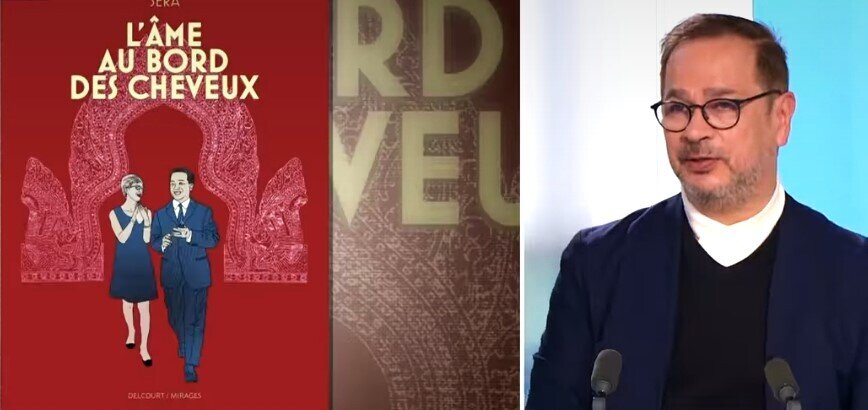

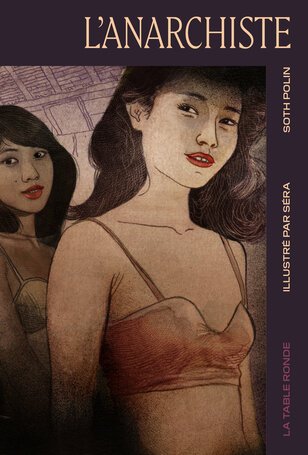

L'anarchiste [The Anarchist]

by Polin Soth & Séra

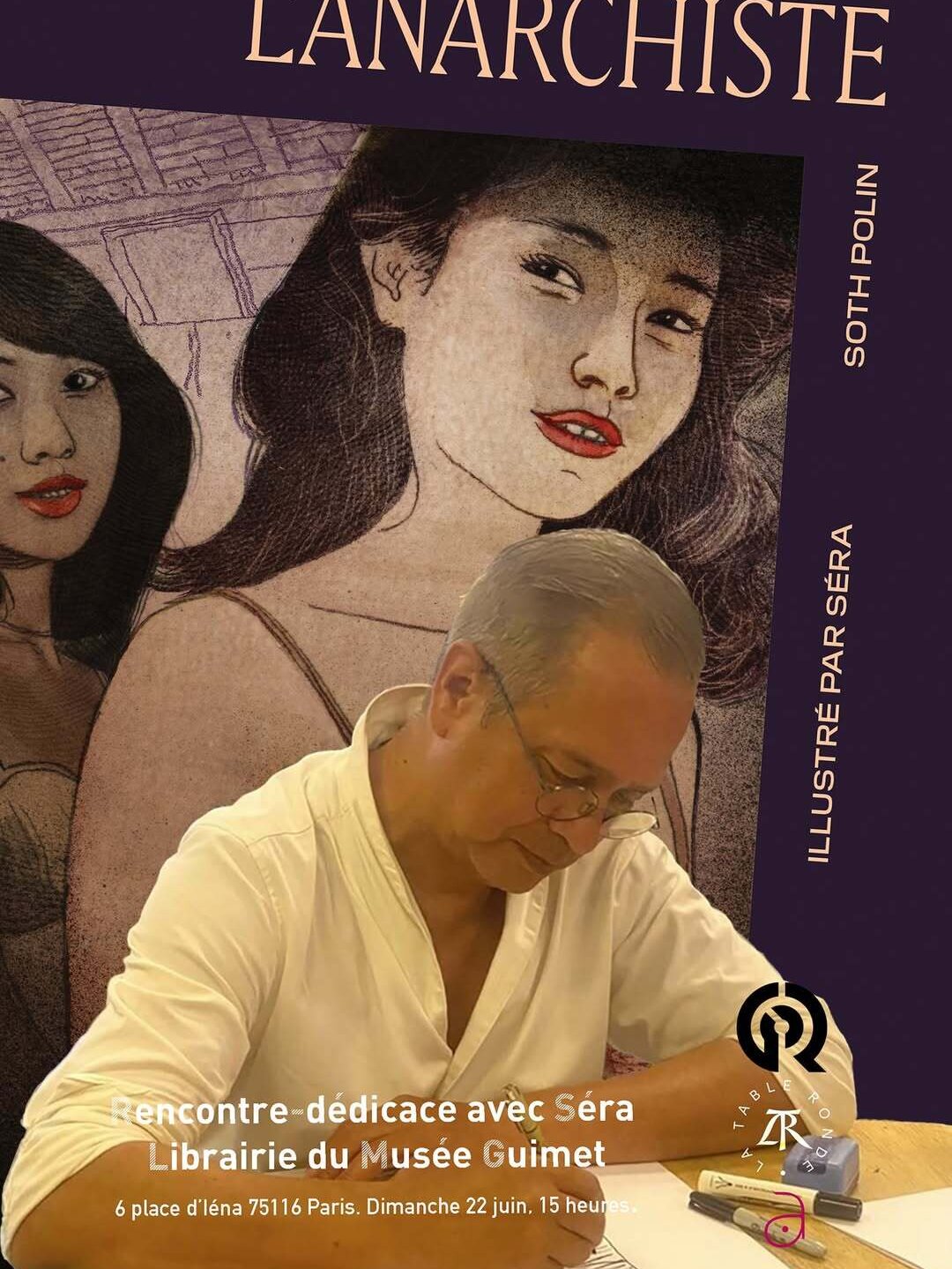

The reprint of a Cambodian cult novel enriched with visual artist Séra's haunted illustrations.

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- Paris, La Table Ronde, 2025. ©Séra for all illustrations including book cover.

- Edition

- 2025 illustrated edition; 1st ed. 1980, 2d ed. 2011.

- Published

- 2025

- Authors

- Polin Soth & Séra

- Pages

- 245

- ISBN

- 970-10-371-1508-9

- Language

- French

This timeless oeuvre au noir — alchemy concept referring to the necessary phase of fragmentation-dissolution of any substance before its possible sublimation — is precisely dated: 23 January 1979, one month after the Vietnamese forceful intervention in Cambodia that was aimed at topple the Khmer Rouge régime, to erase (if that was possible) “three years, eight months and twenty days” of terror, as the proverbial counting goes.

Yet the darkly vivid matter the author deals with definitely remains immemorial. The novel — or a stunning combination of two differently dated and written in two different languages — is adverse to time: it even pretends to deal with the uncertain moment when life is leaving a living body, this threshold between what we know too well and what we suspect in the most abandoned moments: “Chaque fois que je fais l’amour, je pense à notre moment de vérite: à la mort!” [Everytime I’m making love, I think of our real moment of truth — death!] (p 24)

Enter the world according to Virak-Polin — since the narrator, a Cambodian exile turned into a cab driver in Paris shares so much with the author a flamboyantly successful writer in his homeland before suddenly fleeing chaos and death six years earlier. His story is deeply embedded in the flow of world affairs, war, diplomatic betrayals, and yet expresses feelings that speak to us no matter where we are from or in which historical context we’re trying to live and survive. As Patrick Deville notes in his preface,

c’est un roman politique et historique, [mais] un roman de la folie surtout, du sexe et de la mort et de notre universelle condition. C’est à la fois le pari et le privilège de la littérature, dont la lecture gagne à s’éloigner de la réalité des faits. Les années passent, les lecteurs changent, les toiles de fond s’effacent, demeure l’essentiel. [This is a political and historical novel, yet above all it is a novel of madness, of sex and death, and of our universal condition. Here is both the gamble and the privilege of literature — reading it benefits from comes out better off, whose reading benefits from moving away from factual reality. Years pass, readers change, backdrops fade, essential remains.

According to historian Penny Edwards, who has been so far the first to translate parts of The Anarchist into English — as of 2025, a full literary translation is still much needed — the novel “flouts the mythology of “la belle France” and takes us to an entrepôt of broken dreams where the trauma of war haunts a Cambodian émigré, whose monologue comprises the second half of the novel. In Paris, weeks after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, the Cambodian taxi-driver Virak unburdens himself of a terrible secret. His audience is fresh road-kill: a young English tourist who is a victim of his distracted driving. Unlike other Europeans in the novel, who impose their own journalistic or ethnographic narratives on Cambodia, she cannot talk back.”

In hindsight, it is hard not to associate the fiction of this young, “flower-like” English tourist dying in a fiery crash on the Seine River bank in the heart of Paris with the fate of a much more famous British luminary in the tragic night of 31 August 1997. Although history and fiction may combine in hallucinatory coincidences, what makes this novel so powerful is certainly the author’s choice of conflating two utterly different texts, one written in Khmer during the author’s heyday and so deliberately provocative at the time that it was banned in Cambodia only to be republished under the mantle with huge success (1967), the other in French and dealing with a period of anguish culminating in the self-emasculation of the narrator. The magic is in the fact they read as one single, compelling work of fiction. How could that be done?

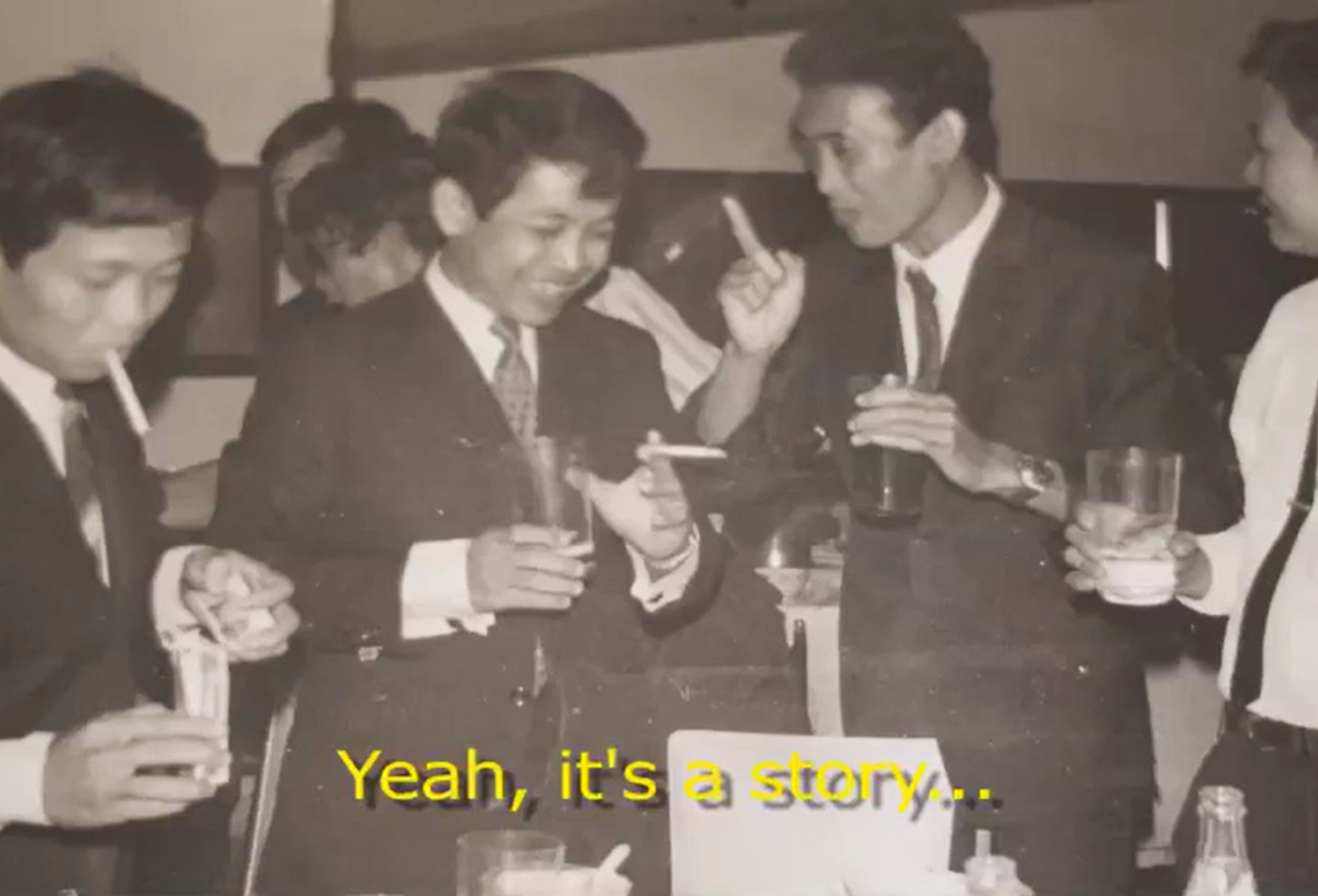

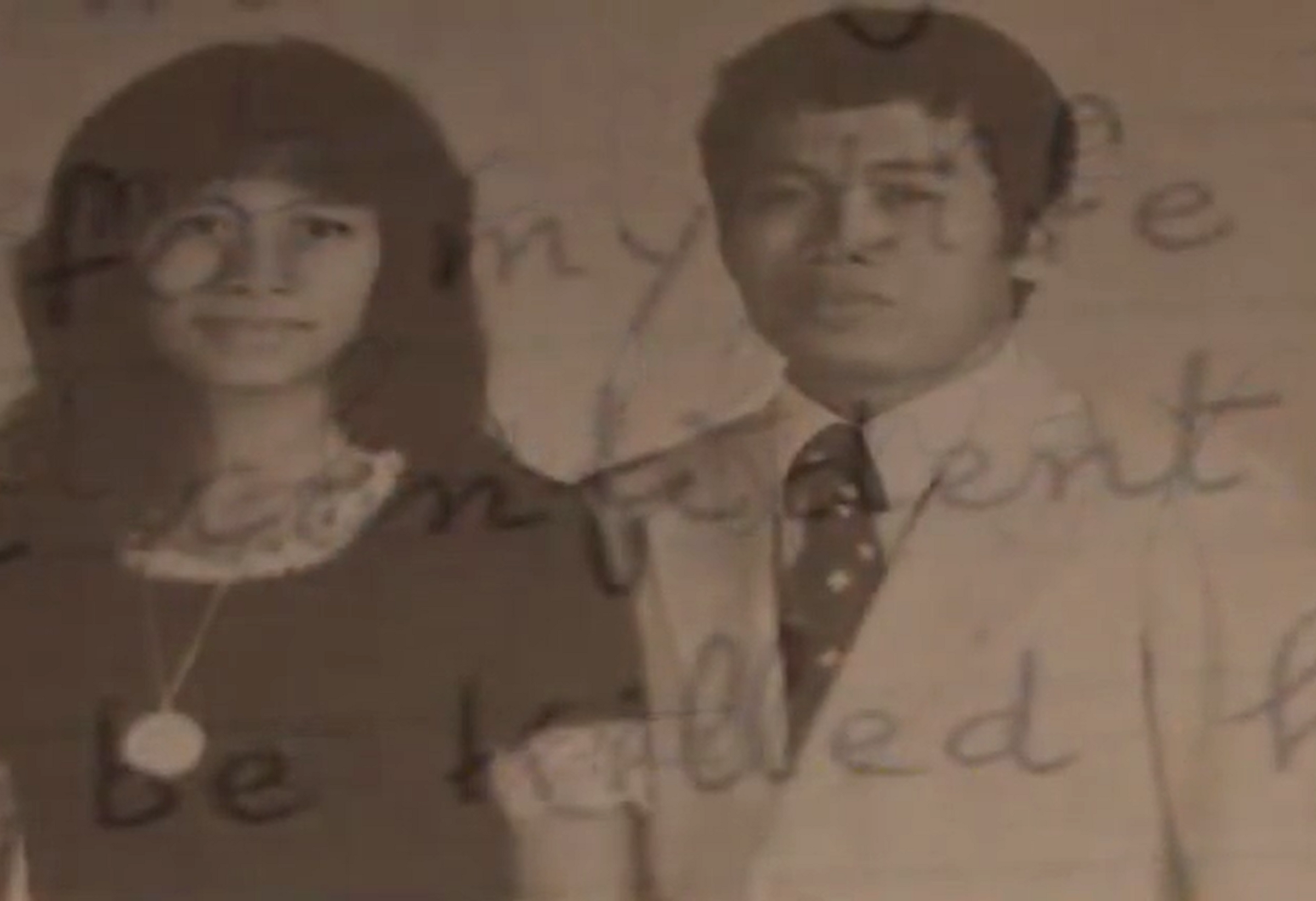

Tradition and Subversion: The Woman Factor

While he was successfuly publishing in Cambodia, both as a fiction writer and a radicalized newsman, Soth Polin was living the rather conventional life of a middle-class, well-read and well-connected young man. In the novel, he recalled his traditional, arranged wedding, complete with the compulsory trip to Siem Reap and Angkor on the occasion. The fiction he was writing in that time period was deliberately erotic, with lots of go-go or karaōke girls and, in the case of Pitiless Provocation, centering on a man having furious sex with one of his sisters-in-law, supposedly an absolute taboo but in fact a widespread transgression in a country where conjugal unions were most often dictated by family interests.

In the second part of the novel, Virak the exiled cab driver father of two will look back on the affair, the almost comical way the two lovers were caught red-handed, so to speak, and the ensuing scandal that allegedly ruined his civil servant career and, more significantly, the trust both fathers had in him. It happened at a time when the Cambodian social fabric was being ripped by political crisis, guerilla unrest, the growing threat that the American war against Vietnam spill over the border, and the exploding corruption of the military régime of General Lon Nol. Times when “the female body had become a contested site between discipline and freedom,” to quote scholar and researcher Klairung Amratisha who, in her essay on Soth Polin’s writing before the exile, noted

Soth’s key to success as a writer lies in his ability to mix the ‘old’ and ‘new’ aspects of literature. While the storyline is created according to the traditional Khmer concept, the author employs a contemporary environment where Western philosophy provides an answer to social problems. Moreover, the story is artistically told through modern and multilayered literary techniques giving the reader the freedom to enjoy it politically, philosophically or pornographically. [Klairung Amratisha, “Women, Sexuality and Politics in Modern Cambodian Literature: The Case of Soth Polin’s Short Story,” MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, Special Issue No.14, 2007, p 76 – 91.]

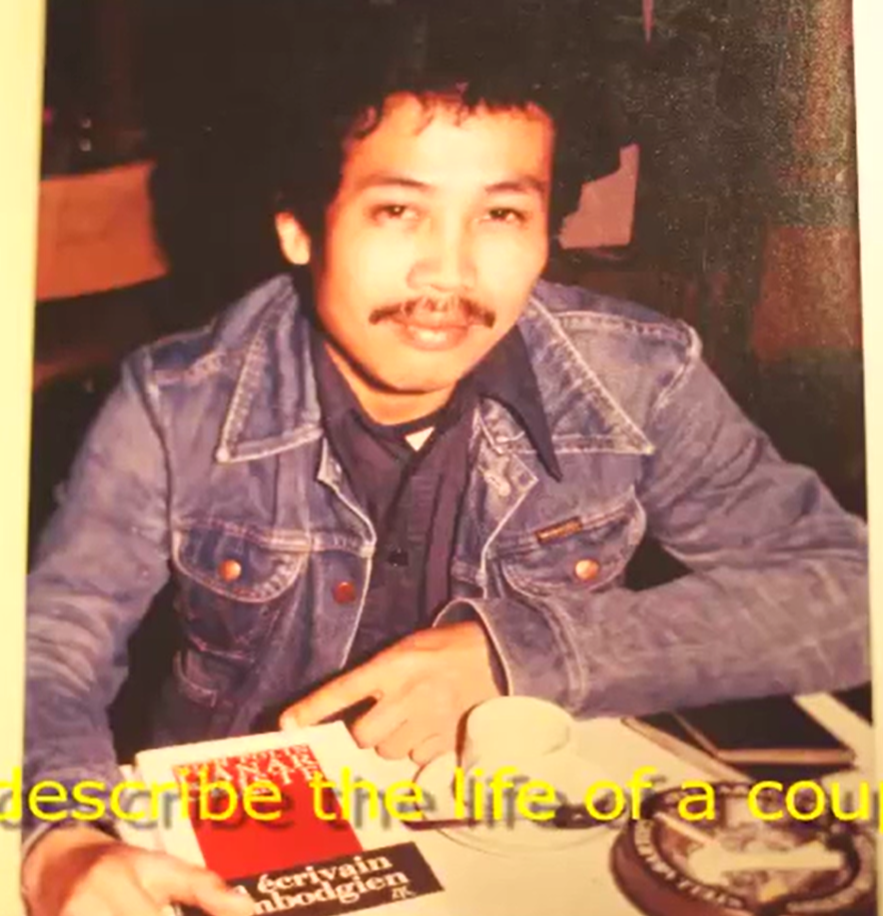

From Soth Polin’s “family album”: pictures (including a wedding one, and the author after the Paris publication of his novel’s first edition in 1980) screened in the short film The Anarchist: The Odyssey of Soth Polin, an extract posted on Vimeo on 6 Aug. 2014.

From Soth Polin’s “family album”: pictures (including a wedding one, and the author after the Paris publication of his novel’s first edition in 1980) screened in the short film The Anarchist: The Odyssey of Soth Polin, an extract posted on Vimeo on 6 Aug. 2014.

From Soth Polin’s “family album”: pictures (including a wedding one, and the author after the Paris publication of his novel’s first edition in 1980) screened in the short film The Anarchist: The Odyssey of Soth Polin, an extract posted on Vimeo on 6 Aug. 2014.

From Soth Polin’s “family album”: pictures (including a wedding one, and the author after the Paris publication of his novel’s first edition in 1980) screened in the short film The Anarchist: The Odyssey of Soth Polin, an extract posted on Vimeo on 6 Aug. 2014.

From Soth Polin’s “family album”: pictures (including a wedding one, and the author after the Paris publication of his novel’s first edition in 1980) screened in the short film The Anarchist: The Odyssey of Soth Polin, an extract posted on Vimeo on 6 Aug. 2014.

While it would be far-fetched to claim that the Cambodian author not only powerfully depicted the gender oppression of women but also opposed it, there is an ongoing paradox amongst his recent readership: younger female readers, in particular from the USA, tend to acknowledge Soth’s literary quality yet lament his “misogyny.” However, particularly in the novel discussed here, it is obvious that female characters are not only stronger, more capable of facing the worst reversals of fortune — “alors que l’homme se ruine totalement dans ses spéculations obsessionnelles” [“while men utterly wreck themselves into their obsessive speculations,” remarks Virak to a friend in L’Anarchiste, adding half in jest, half seriously: “Tu comprends maintenant pourquoi… Pourquoi je suis si misogyne?” [now you understand why…why I am such a misogynist?”] -, they’re also able to survive the loss of one’s nation, they become a nation in exile for exiled men, even if they don’t really seek that substitution.

Tomoko Okada 岡田知子 (born February 1966), a Japanese literary scholar at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies who translated several short stories by Soth, has shared her vision of his work, remarking that “the women described in the stories assert their rights, enjoy being free and unrestrained, and challenge the traditional expectation of the virtuous woman who is modest and obedient to her husband.” [Introduction to the Modern Short Stories from Cambodia translated into Japanse, 2001]. And in her profile of Soth Polin in 1995, newswriter Janet Wiscombe quoted him claiming that “I have contempt for men who take advantage of women financially and physically,” adding: “By his own definition, Soth is a rebel, a man between cultures, a tortured writer prone to pessimism and depression. Maybe so. But he’s also a highly social creature who bombs around town on Rollerblades and dreams of owning a Harley. He is a cosmopolitan intellectual who’s studied at the Sorbonne, a linguist who’s published books in both Cambodian and French (the only Cambodian to have published fiction in French), a lover of philosophy who quotes Nietzsche and Kant, Sartre and Kierkegaard.” [“The Power of His Pen,” Long Beach Press-Telegram, 19 Nov. 1995].

Back to fiction: when his marriage with Myra is about to tank, when Virak’s own desperate obsessions are definitely taking over, his love-making with his wife evolves into an anguished discussion on some essential, urgent and obviously non-arousing topics. Self-conscious in bed — and consumed with sexual jealousy -, he muses:

Ma chérie, les conquérants et les bâtisseurs sont maintenant balayés par les barbares. Qu’est-ce qu’ils ont de plus que nous, ces Viets? Qu’est-ce qu’ils ont construit? Rien. Ils ont commencé par le pragmatisme confucéen. Le vulgaire l’a toujours emporté sur la finesse, et maintenant ils brandissent le marxisme triomphant, ils incarnent l’Histoire. Et l’esprit bascule dans la matière. Pour nous c’est la méme finalité, notre ineluctable extinction. Le tocsin sonne… cest vraiment la fin, la fin du peuple angkorien, plus artiste que commerçant, plus avide des voluptés et des divinités que des spéculations terrestres. C’est pour cela que je voudrais retrouver la racine du MAL qui nous a perdus.

– Je né vois pas le rapport… ce n’est pas en faisant l’amour que tu la trouveras.

– Tu peux peut-être m’apporter quelque lumière. […] L’homme est moins bien placé que la femme pour saisir la divinité du plaisir, pour posséder le sens de la volupté.

[My darling, the conquerors and builders are now swept away by the barbarians. What do these Vietnamese have that we don’t? What have they built? Nothing. They started with Confucian pragmatism. Vulgarity has always prevailed over finesse, and now they brandish triumphant Marxism, they embody History. And spirit is falling into matter. For us, it’s the same end, our inevitable extinction. The alarm is ringing… it truly is the end, the end of the Angkorian people, more artist than merchant, more eager for pleasures and divinities than earthly speculations. That’s why I would like to find the root of the EVIL that has lost us.

–I don’t see the connection… it’s not by making love that you’ll find it.

–Perhaps you can shed some light on here. […] Man is less equipped than woman to grasp the divinity of pleasure, to possess the sense of voluptuousness.] [p 185]

Angkor as Idealized Cambodianess?

The Angkorian past of Cambodia is one of the few topics that Soth’s devastatingly critical mindset has spared. Since his young age, he had avidly read history books and publications, and at the end what we know about these centuries remained in his mind as the only untainted part of the saga. Idealized, probably, but as in the eyes of a child: as wondrous as the unknown. In the first part of the novel, he recalls the lovely terror at swimming in dark waters and thinking of the choeung kap [p 46], an ancient and mysterious Khmer term still in use and here referring to lurking water creatures who might or not grab you by your feet and pull you down the abyss.

At the time “the castrated man turned into a cab driver crashed his car and his innocent passenger, the world was discovering, or starting to accept discovering, what had happened in Cambodia since April 1975. In real life, the writer has been trying to sound the alarm but it is now too late and this sense of failure was to encompass his whole adult life:

Ma petite Anglaise esquintée, tu né me contrediras pas, mon amie, tu né le peux pas, tu as la bouche pleine de sang. et moi je veux parler, parler vite, parler beaucoup et très vite… Mais je né peux pas leur en vouloir à ces journalistes-là. Parce que moi aussi, je suis journaliste. Je les comprends, d’autant mieux que je suis de la pire espèce. Je me croyais un bon type, un journaliste honnête, un saint. Il n’y a pas de saint honnête. Si ignobles que soient ces canailles, ils né le seront jamais autant que moi, le journaliste «honnête». Il y a belle lurette que la plume né prétend plus incarner la loyauté et l’honneur, comme l’épée et la lance dans les anciens temps. Ah… Je voudrais tant me transporter à cette époque d’Angkor, où les rois s’en allaient à dos d’éléphants au-devant de leurs adversaires. Je né veux plus n’être que cette plume peureuse, qui pour faire mal se réfugie crânement derrière une froide armure, une monstrueuse abstraction: l’opinion publique! [My little, banged-up Englishwoman, you won’t contradict me, my friend, you can’t, your mouth is full of blood. And I want to talk, talk fast, talk a lot and very fast… But I can’t blame those journalists. Because I too am a journalist. I understand them, all the better because I am of the worst kind. I thought I was a good guy, an honest journalist, a saint. There are no honest saints. However ignoble these scoundrels may be, they will never be as ignoble as me, the “honest” journalist. It’s been a long time since the pen claimed to embody loyalty and honor, like the sword and the lance in ancient times. Ah…I would so much like to transport myself to that time of Angkor, where kings rode on elephants to meet their enemies. I no longer want to be just that cowardly pen, which, in order to cause harm, bravely hides behind a cold armor, a monstrous abstraction: public opinion![p 157]

High on the list of nonsense served to the Western public opinion by some journalists was a piece of Khmer Rouge propaganda that he particularly loathed: the claim that all the great public works completed by Cambodians forced to labor until they dropped dead was a modern replica of monumental achievments at Angkor:

Je bois trois bières coup sur coup, en attendant. Un Français, bien habillé, propre, le teint påle, sirote son armagnac à mes côtés. Il engage la conversation avec moi: “- Vous êtes vietnamien? — Non, cambodgien. — Ça va un peu mieux le Cambodge, n’est-ce pas? Oui, ça né va pas mal, répondis-je. Un pays bourré de squelettes comme un fantastique cauchemar. — Bof! n’exagérons rien. Ce qui est exagéré est insignifiant. Disons que le régime khmer rouge est austère et spartiate. C’est plutôt une révolution fascinante, non? Des travaux angkoriens! — Ah oui? Vous avez vu la photo où des hommes tirent la charrue à la place des bœufs? — Oui… oui… il paraît qu’ils ont des problèmes dans l’agriculture, mais c’est provisoire.” Me voilà encore devant un chrétien marxisant. Je me demande subitement si ce n’est pas celui-là qu’il faut éventrer… “- Mais les Khmers rouges ont bouffé le clitoris de ma femme, dis-je très fort, et d’un ton si poignant parce que justement Myra m’obsède… — Ah! s’exclame-t-il, sidéré, gobant cette énorme plaisanterie, tandis que le petit verre d’armagnac lui échappe des mains et se brise par terre en morceaux. [I drink three beers in a row while I wait. A well-dressed, clean, pale-skinned Frenchman sips his Armagnac beside me. He starts a conversation with me: “Are you Vietnamese?” “No, Cambodian.” “Cambodia’s a little better, isn’t it? Yes, it’s not bad,” I reply. “A country full of skeletons like a fantastic nightmare.” “Meh! Let’s not exaggerate. What’s exaggerated is insignificant. Let’s say the Khmer Rouge régime is austere and Spartan. It’s rather a fascinating revolution, isn’t it? Angkorian works!” “Oh yeah? Have you seen the photo where men pull the plow instead of oxen?” “Yes… yes… they apparently have problems in agriculture, but it’s temporary.” Here I am again in front of a Marxist-leaning Christian. I suddenly wonder if this isn’t the one that needs to be disemboweled… “But the Khmer Rouge ate up my wife’s clitoris”, I say very loudly, and in such a poignant tone because Myra obsesses me… “Ah!” he exclaims, stunned, swallowing this enormous joke, while the small glass of Armagnac slips from his hands and shatters on the ground into pieces. [p 183]

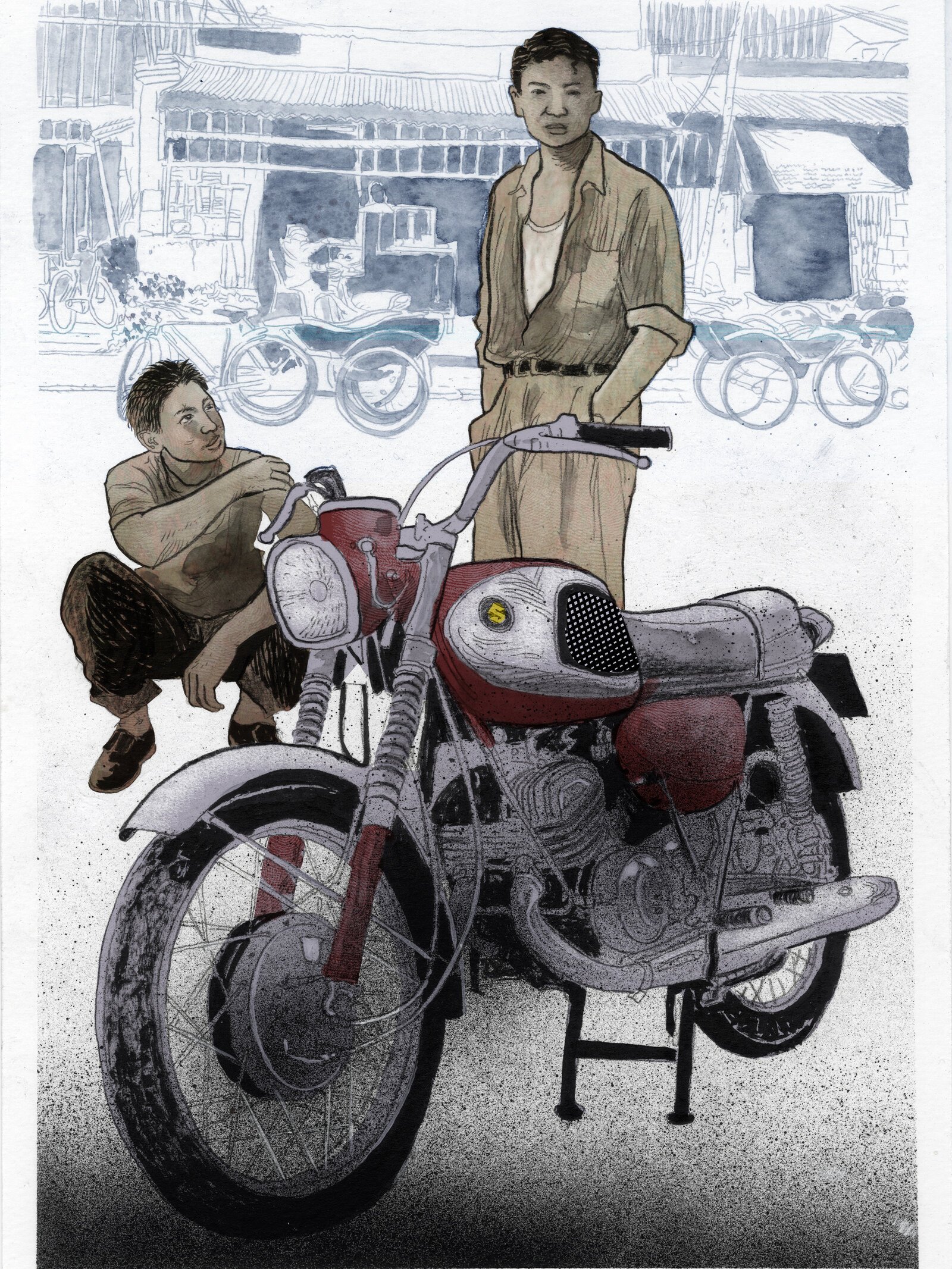

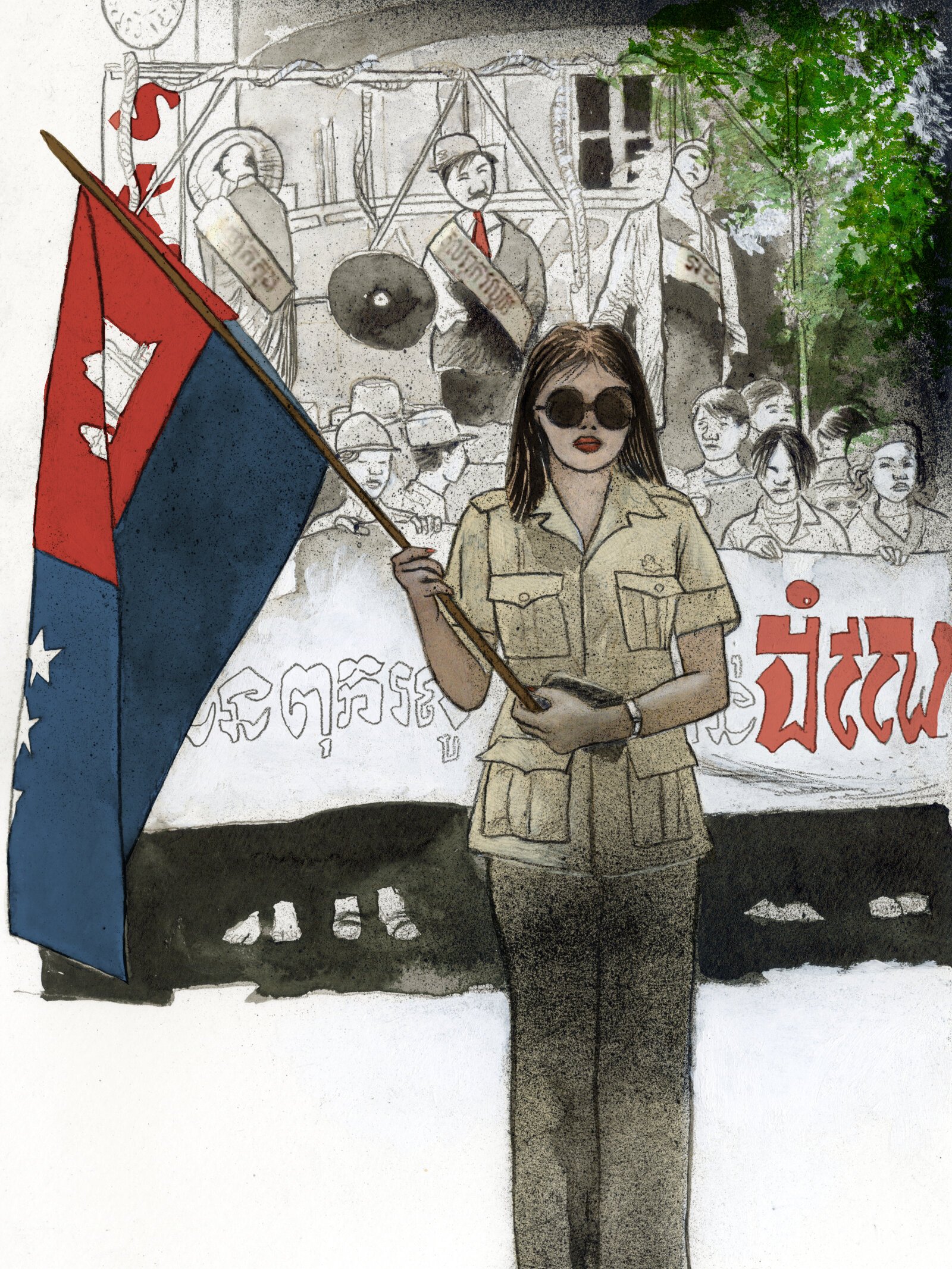

Séra, “Deux amis” [Two Friends] and “République khmere” [Khmer Republic], illustrations for L’Anarchiste, 2025 (courtesy of the artist). ©Séra

The former journalist has ceased to believe in the virtue of communication: in his short story “Communicate, they say,” he was becoming more taciturn than ever during an outing to the beach with boy and girl friends, their endless small talk…Talking is inconvenient because it may expose one’s fickleness:

Parce que enfin l’âme humaine est versatile et insaisissable comme une quelconque goutte d’eau roulant de tous côtés sur une feuille de nénuphar. La mienne est probablement l’esquisse la plus folle entre toutes les esquisses: une virtuose de la fluctuation. Mon âme n’est qu’illusion, mirage sans consistance. Mais les illusions se soutiennent entre elles, elles s’entretiennent les unes les autres. Une illusion a besoin d’autres illusions, comme la flamme d’une chandelle se place devant un miroir à plusieurs faces afin de s’y confirmer. [Because, after all, the human soul is fickle and elusive, like any drop of water rolling from side to side on a waterlily leaf. Mine is probably the craziest outline of all outlines: a virtuoso of fluctuation. My soul is nothing but illusion, a mirage without substance. But illusions support each other, they sustain each other. An illusion needs other illusions, like the flame of a candle placed in front of a multi-sided mirror in order to confirm itself.][p 163]

And the final assessment, a deluge of questions right before The End: “Fils pieux, j’ai ruiné mes parents. Monarchiste, j’ai fait la révolution. Nationaliste, j’ai trahi les nationalistes. Est-ce que je suis bien moi? Est-ce que Mona était la vraie femme que j’aimais? Est-ce que sa chatte était une vraie chatte? Ou l’intelligence d’une sorcière qui s’y substituait?” [“A loving son, I wrecked my parents. A monarchist, I became a revolutionary. A nationalist, I betrayed that camp, too. Am I really myself? Was Mona the real woman I loved? Was her pussy a real one? Or was it a sorcerer’s cleverness acting the part of it?”] [p 245]

About the illustrations

Artist Séra has intimately related to this novel for many years, one profound reason being that he, like the author, lost his father in the civil war. In 2005, he contributed a live painting performance to the art film L’Anarchiste inspired by Soth Polin’s novel, filmed by Rithy Panh and Pierre Wallon, music by Vealsrè pop-punk band [1], at burnt-out Suramarit Theater [2], Phnom Penh.

From the song’s letters:

croire en rien | rien ma vie s’écoulait comme une lente | hémorragie | elle se vidait de sa substance dans une | espèce de fuite en avant | [une] journée passée était pour moi comme un | délabrement | continu une page envolée une pièce | perdue un pétale fané | mporté au hasard des vents sans retour.

[Believe in nothing | nothing my life flowed by like a slow | bleeding | running out of its substance in a | kind of headlong evasion | [a] day gone by was for me like an | unrelenting decay | vanished page, lost piece | faded petal | blown away at random, never to return.]

[1] Luk Haas, a pop-punk music radio producer, recalled in 2015: “This band, Vealsre, is made up of two Cambodians and two French guys. They don’t exist anymore. The French guys were working as French teachers, I think, in the country. The Cambodians were guys…connected somehow to the French community. They decided to do some rock in Khmer, something which was never made before, at least since the mid ’70s. From the ’60s to the ’70s, they had rock in Cambodia, before the Khmer Rouge took power. Then, everybody was killed. Now they are re-starting the scene. So, Vealsre does not exist anymore, but they did two CDs. It’s not straight punk. They went on to do another band called Teuk Mate, with one CD. That band split, and now they are called Thom Thom, with two Cambodians — one girl playing bass and one guy playing guitar and singing — and one French guy playing the drums. They say they are a Cambodian garage band. Vealsre was a little bit soft, now they want to do something really…[harsher]. They are touring like hell in the Cambodia. They go to the countryside, where nobody had ever heard of rock ’n’ roll, and they jam for the people in the villages. Somehow, they are starting some kind of scene. It’s too early to tell. They are one of the only bands doing this kind of stuff.”

[2] Designed by chief national architect Vann Molyvann in 1966, the Grand Théâtre Preah Bat Norodom Suramarit (or Mohorsrop Theatre) opened in 1968. An accidental fire during renovation in February 1994 devastated the entire auditorium to the sorrow of Phnom Penh denizens, and all projects to rehabilitate the elegant building remained unsuccessful. Right before the site’s handling to developer Kith Meng for complete destruction in early 2005, acclaimed filmmaker Rithy Panh’s shot the docudrama The Burnt Theater, set in the building remains and depicting a theater troupe struggling to keep their art alive.

Tags: Cambodian literature, civil war, Cambodian writers, women, sexuality, Khmer Rouge, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s

About the Author

Polin Soth

Soth Polin [also Suddh Pulin] សុទ្ធ ប៉ូលីន( b. 1943, Chroy Thmar village, Kompong Cham, Cambodia) is a Cambodian writer who published to great acclaim his first novel, A Meaningless Life, in 1965, during the Sangkum Reastr Niyum era, a renowned journalist who worked with Khmer Ekareach (The Independent Khmer, newspaper launched by his uncle Sim Var, and founded with writer Sin Kim Suy the newspaper and publishing house Nokor Thom - នគរធំ (The Great Kingdom).

Fluent both in French and Khmer, he studied Cambodian literature as well as Western philosophy since his childhood. His maternal great-grandfather was the poet Nou Kan, authot Teav-Ek ទាវឯក, a variation on the time-honored Khmer love story Tum Teav. In his only lenghty interview (by phone, in Sept. 2003)) with researcher and editor Sharon May (“Beyond Words: An Interview with Soth Polin,” In the Shadow of Angkor: Contemporary Writing from Cambodia, Frank Stewart and Sharon May eds., Chiang Mai, Silkworm Books, 2004, pp 11 – 22), he said he “learned to write in imitation of Cambodian poetry, but when I wrote on my own, it was in prose.” [p 13]

As a young, successful and controversial writer, Soth Polin was caught in the tumultuous politics of Cambodia in the shadows of the Vietnam war, becoming highly critical of Prince Sihanouk’s neutralism and the growing influence of communism on Cambodian intellectuals. Through Nokor Thom, he initially supported the pro-American coup of General Lon Nol before distancing himself, finally taking refuge in France right after the assassination of Thach Chea, Deputy Minister of Education and a close friend, on 4 June 1974.

Soth Polin was one of the first Cambodian [and non Cambodian, as a matter of fact] intellectuals to raise the alarm about the Khmer Rouge’s abuses in 1976 and 1977 publications bylined by French journalist Bernard Hamel. He was deeply affected by exile — and the killing of close family members by the Khmer Rouge, including his own father‑, remarking in the 2003 interview with Sharon May:

When you lose your country, you lose everything. If you’re a writer, you no longer get the echo of your readers. […] In West Berlin when I was homesick I translated that Cambodian song, “Phot Chong Chroy” [Missing the Cape.] [1] There were no other Cambodians there besides my wife. The song compares Cambodia to the woman you love. […] It says, “If I lose my country, I miss nothing, but if I lose a woman, I miss everything. I’m utterly desperate. In reality, the country and the woman are the same, and he misses it all. That song, I think, was written for a traveler.” [op.cit., p 15]

Exiled in Paris, he worked as a taxi driver, completed a French-Khmer dictionary, and worked on what was to become a cult novel, L’Anarchiste [The Anarchist], 1980. The narrator of this profundly dark- text allows in the closing lines: “Fils pieux, j’ai ruiné mes parents. Monarchiste, j’ai fait la révolution. Nationaliste, j’ai trahi les nationalistes. Est-ce que je suis bien moi?” [“A loving son, I wrecked my parents. A monarchist, I became a revolutionary. A nationalist, I betrayed that camp, too. Am I really myself?] [L’Anarchiste, 2025 ed., p 245].

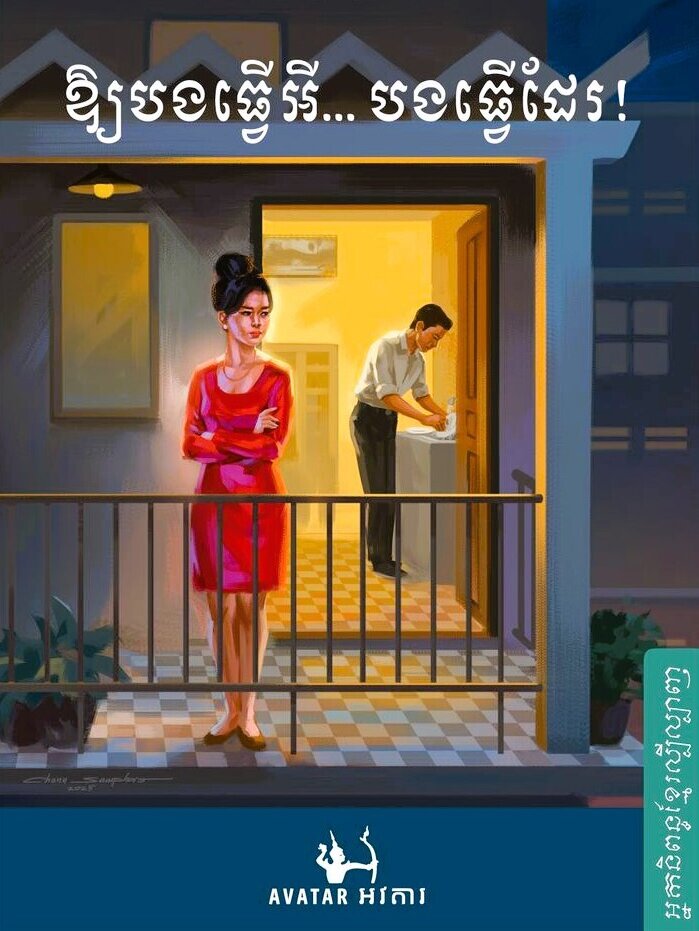

1) Soth Polin in Long Beach, California, April 2017. 2) Reprint of ឱ្យបងធ្វើអី… បងធ្វើដែរ! [Whatever Your Wish…It’s My Command!], Avatar, 2025: book cover by Chan Somphos ចាន់ សម្ផស្ស .

Then, in 1982, he moved to California with his two sons (he had divorced shortly before the acclaimed French publication of his novel), allegedly to reunite with his mother and siblings who had recently emigrated to Long Beach, CA, USA. There, he worked as a cab (and airport shuttle) driver again, and

[I] tried everything to survive. Even gambling. I sold French make-up cream. […] I am ambivalent like Kierkegaard. That is why I like him so much. [Paraphrasing the famous philosopher] If you are married, you’re miserable. If you’re not, you’re miserable. [interview to Janet Wiscombe, “The power of his pen”, Long Beach Press-Telegram, 19 Nov. 1995.]

Soth Polin attempted to rekindle his editorial skills with the short-lived weekly magazine Nokor Thom in 1998 — in association with Cambodian-American businessman Chenda Bourng. Earlier, he had regurlarly published in Sereipheap [Freedom], a tabloid aimed at the Long Beach Cambodian community co-edited with Kem Narin, whom he lived several years before divorcing in 1995. There, he authored serialized novels — among them The Widow from L.A -, and broadcasted radio political programs, some in collaboration with brother-in-law Mam Sonando ម៉ម សូណង់ដូ (b. 13 February 1942), a Cambodian radio journalist and opposition politician. The congenial yet elusive fiction writer has also hinted to several unfinished manuscripts, including Angkor Princess, which he described as “a [fictional] diary written by Jayavarman VII, the greatest king of Cambodia, about his first love in Angkor.” [op. cit., p 18].

[1] ផុតចុងជ្រោយ [Passing-Missing the Headland] is an old Khmer song in which it is said at some point: “If I pass a cape, I miss nothing, but if I pass a nipple, I miss everything.” The metaphor equating the land to the female body continues throughout the lyrics.

Publications

[based on author and translator Christophe Macquet’s ongoing editing, translating and referencing work]

- [with Ke Sokhan & To Chhun] La composition française au DESPC, Phnom Penh, 1964.

- ជីវិតឥតន័យ [Une vie absurde- A Meaningless Life], Phnom Penh, 1965; repub. Nokor Thom, 1970s; repub. Paris, Institut de l’Asie du Sud-Est, c. 1980.

- ខូចសតិព្រោះកាមតណ្ហា [Lust Crazy-Fou de désir], Phnom Penh, 1965.

- ស្នេហ៍អពមង្គល [Misérables amours — Wretched Love], Phnom Penh, 1965.

- អូនជាម្ចាស់ស្នេហ៍ [You Are the Owner of Love], Phnom Penh, 1966.

- ក្ស័យតែម្ដងទេ (We Die Only Once, Phnom Penh, 1967).

- ស្នេហ៍អពមង្គល [ Phnom Penh, 1965].

- Contes et récits du Cambodge, Phnom Penh, Pich-Nil Éditeur, 1966.

- អូនជាម្ចាស់ស្នេហ៍ [Tu es l’amour de ma vie — You’re Love Supreme], Phnom Penh, 1966.

- ក្ស័យតែម្ដងទេ [On né meurt qu’une fois — Blind Everytime], Phnom Penh, 1967.

- ចំតិតឥតអាសូរ [Sans pitié, les fesses en arrière — Showing My Ass with No Mercy or Pitiless Provocation], Phnom Penh, 1967. [banned in Cambodia, clandestinely repub. as ចំតិតទៀតហើយ [Showing My Ass Just a Little More]. [novel tr. and adapted by Soth Polin to become the first part of L’Anarchiste (1980)].

- បុរសអផ្សុក [Un homme s’ennuie — Bored Man] Phnom Penh, 1968.

- ឱ្យបងធ្វើអី… បងធ្វើដែរ [Tout ce que tu me diras de faire.. Je le ferai! — Anything You’ll Tell me to Do…I will!] : 1.ការទាក់ទងគ្នា… 2. បង្គាប់មកបងចុះអូន!…3.អ្វីៗដែលផ្លាស់ប្ដូ!… 4.ឲ្យបងធ្វើអី… បងធ្វើដែរ! Phnom Penh, 1969. | repr. ឱ្យបងធ្វើអី… បងធ្វើដែរ! [Whatever You Order Me… I’ll do!], preface by Chuth Khay ខ្ជិត ខ្យៃ, Phnom Penh, Avatar Publishing, 2025, 236 p.

- [from ឲ្យបងធ្វើអី… បងធ្វើដែរ] ការទាក់ទងគ្នា [Communicate, They Say — Communiquer, disent-ils]: 1/ Japanese tr. as ひとづきあい by Tomoko Okada (岡田知子), Contemporary Cambodian Short Stories — Translation and Publishing (現代カンボジア短編集 — 翻訳出版,), Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, The Daido Life International Culture Foundation (大同生命国際文化基金), 2001. 2/ French tr. as Communiquer, disent-ils… by Christophe Macquet, Europe 889, “Écrivains du Cambodge”, May 2003, and MEET bilingual review 15, Porto Rico/Phnom Penh, 2011. 3/ Eng tr. from Christophe Macquet’s French tr. as Communicate, They Say by Jean Toyama, In the Shadow of Angkor: Contemporary Writing From Cambodia, revue Mānoa, University of Hawaii Press, 2004.

- អ្នកផ្សងព្រេងអារាត់អារាយ [Un aventurier sans étoile — Adventurer with No Goal], Phnom Penh, 1969; repub. Paris, Institut de l’Asie du Sud-Est, 1982.

- មរណៈក្នុងដួងចិត្ត [Death in the Heart - La Mort dans l’âme]:1.ព្រលឹងប្ដីអើយ… ខ្លួនអូនរហែក… 2.រកគន្លឹះប្តីខ្ញុំ… មិនឃើញសោះ… 3.ពស់ក្បាលពីរ… 4.ក្បាលបោកផ្ទប់នឹងជញ្ជាំង… 5.ស៊ូទ្រាំគ្រាំគ្រាយូរមកហើយ… 6.មរណៈក្នុងដួងចិត្ត…, Phnom Penh, 1973; repr. Phnom Penh, Nagardham Publishing House, 2003.

- Kompong Cham, symbole de notre survie (deux ans de pourrissement / les sauveurs), Nokor Thom, Phnom Penh, 1973.

- [preface to] Sang Savat, រឿងមហាចោរនៅទល់ដែន [The Big Thief at the Border — Écumeur de frontière] (1955), repub. Phnom Penh, Nokor Thom, 1973.

- Aperçu sur l’évolution de la presse au Cambodge, avec Sin Kim Suy, Phnom Penh, 1974; ENG version in Newspapers in Asia: Contemporary Trends and problems, John A. Lent ed., Hong Kong: Heinemann Asia, 1982: 219 – 37.

- Dictionnaire Français-Khmer, Phnom Penh, 1974.

- ស្រុកយើងមានសន្តិភាពមែនឬ? [Is our Country Peaceful?], Phnom Penh, Nokor Thom, 1974.

- ស្រុកយើងអើយវេទនាដោយសារគេ [Why our Country is Suffering], Phnom Penh, Nokor Thom, 1974.

- Témoignages sur le génocide du Cambodge, collection de témoignage de réfugiés cambodgiens à la frontière thaïe, Paris, S.P.L., 1976. [co-written with Bernard Hamel].

- De Sang et de Larmes : la Grande Déportation du Cambodge, Albin Michel, Paris, 1977. [co-written with Bernard Hamel without author’s mention].

- Petit dictionnaire français-khmer, Boulogne-Billancourt, CAMA [Comité inter-missions pour les réfugiés du Sud-Est asiatique en France], 1980.

- “La diabolique douceur de Pol Pot”, Le Monde, 19 mai 1980 | ENG “The diabolical sweetness of Pol Pot”, In The Shadows of Angkor, Contemporary Writing from Cambodia, Sharon May ed., Manoa, University of Hawai’i Press, 2004: 23 – 27.

- L’Anarchiste (Éditions de la Table ronde, Paris, 1980; repub. 2007, Poche collection, 2007; repub. 2011 [preface by Patrick Deville]; repub. 2025, with illustrations by Séra. | The Anarchist, extracts tr. by Penny Edwards, Words Without Borders Magazine, Nov. 2015, in Mekong Review, Vol1‑1, Nov. 2015 and Out of the Shadows of Angkor: Cambodian Poetry, Prose, and Performance through the Ages, revue Mānoa, University of Hawaii Press, 2022. | L’anarchico tr. into Italian by Alessandro Giarda, Asia/Cambogia, Obarrao Edizioni, 2019.

- “L’histoire d’une malédiction (ou le malheur d’être cambodgien)”, Revue universelle des faits et des idées (RUFI), Paris, 1980.

- “Et le Cambodge bascula dans la guerre”, RUFI, 1980.

- “Et Bouddha, le “saccageur de rêves” usurpa le trône divin”, RUFI, Paris, 1981.

- “Histoire du jeune moine qui voulut être crocodile”, RUFI, 1981.

- “Hari-Hara ou la divinité fondatrice d’Angkor”, RUFI, 1982.

- Des lunettes pour la frime, short story, Paris [unpublished].

- Du café sans sucre, short story, Paris [unpublished].

- អ្នកមេម៉ាយនៅអិល‑អេ [The Widow from L.A.], Long Beach, 1993.

- ស្នេហាដាច់ខ្យល់នៅឡាសវ៉េហ្គាស [Love Vanishes in Las Vegas — Les amours agonisent à Las Vegas], Long Beach, 1995.

- [theater play] បាក់ធ្មេញ [La Dent cassée — Broken Tooth], Long Beach, 1995.

- ស្ដេចចង់ [The Game of The King’s Wishes — Le Jeu du Roi désir]: 1.ស្ដេចចង់ 2.កសាងស្រមោលអតីត 3.ក្លិនតណ្ហានៅហ្វ្រេស្ណូ, Long Beach, 1992; ENG tr. as Demonic Fragrance by the author’s sons Bora Soth and Norith Soth in 1992 [unpublished]. កសាងស្រមោលអតីត, 2d short story in the collection tr. from Khmer by Christophe Macquet as Nul né peut faire revivre les morts, Jentayu, magazine de littérature asiatique vol. 9, 2019.

- Les chemins de l’Apocalypse, 1998, 350 p. [unpublished].

- ជីវប្រវត្តិសង្ខេបនៃទស្សនវិទូក្រិកដ៍ល្បីល្បាញជាងគេក្នុងបុរាណកាល [KH translation of François Fénelon, Abrégé des vies des anciens philosophes], Phnom Penh, Angkor Borey, 2004.

- Political Squibs Online [Pamphlets politiques en ligne], Devaraja, 2005. [various articles on Cambodian politics including Kampuchea Krom, in KH].

- Génial et génital, tr. of ឲ្យបងធ្វើអី… បងធ្វើដែរ! four short stories (Phnom Penh, 1969) by Christophe Macquet [tr. and introduction], Editions Le Grand Os, France, 2017.

- The Aroma of Desire in Fresno, tr. from Khmer by Bora Soth & Norith Soth, Out of the Shadows of Angkor: Cambodian Poetry, Prose, and Performance through the Ages, Mānoa, University of Hawaii Press, 2022.

- Command Me to Exist, translated from Khmer to French by Christophe Macquet and from French to English by Françoise Bénichou, Out of the Shadows of Angkor: Cambodian Poetry, Prose, and Performance through the Ages, Mānoa 33 – 2 and 34 – 1, University of Hawaii Press, 2021 – 2022, pp. 161 – 167.

Films, Theater Plays

- Rithy Panh, L’Anarchiste, art film inspired by Soth Polin’s novel (5:21 min), filmed by Rithy Panh and Pierre Wallon at burnt-out Suramarit Theater, Phnom Penh, 2005, live music by Vealsrè pop-punk band, live painting performance by Séra.

- Jean Baptiste Phou [adaptation from Soth Polin’s novel and staging], L’anarchiste, , filmed at Anis Gras, Arcueil, France, 24 March 2014. A CoolCat/GreenMango/KH Say production (77 min on Vimeo) with Jean Baptiste Phou (Virak), Elisabeth Bardin (The English Girl/Marie), Sarosi Nay (Savouth), Dara Chek (Savouth’s voice over), Sophie Belissent (Marie’s voice over), Bopha Chheang (Virak’s daughter voice over); Choreography and Khmer Dance: Sarosi Nay, Kim Lay Ley; Costumes: Victor Melchy, Alina Profir; Video Archive Editing: Jean Baptiste Phou; Sound: Clovis Tisserand, Sevrine Guims.

main photo: Seth Polin at the launch of his novel L’Anarchiste, Paris, 1980.

About the Illustrator

Séra

Ing Phousera, artist’s name Séra (b. 1961, Phnom Penh, Cambodia) is a visual artist who has been exploring the themes of exile, civil war, social amnesia and remembrance.

Escaping the Khmer Rouge storming Phnom Penh in 1975, he took refuge in France with her mother and two siblings, while their father fell prey of the terror régime. It is only in 2023 that he explicitely mentioned such tragic circumstances in his latest graphic novel L’ame au bord des cheveux (Delcourt, Paris). In an interview with French daily L’Humanité, he recalled in 2023: “En une joumée, tous les habitants du quartier disparaissent, obéissant aux soldats qui les envoient dans les campagnes. Je me souviens de quinze jours d’attente angoissante à l’ambassade de France, sans savoir ce qui va nous arriver. J’ai 13 ans. […] Mon père reste convaincu que les Cambodgiens né s’entre-tueront pas éternellement, que les choses vont s’arranger. N’ayant pas la nationalité française, contrairement à nous, son rapatriement est incertain. Finalement, l’ambassade livre mon père aux Khmers rouges, et nous envoie en camion jusqu’à la frontière. Les autorités françaises ont livré des dizaines de Cambodgiens réclamés par les Khmers rouges. Quelle bêtise …Cinquante-huit passeports ont été utilisés pour protéger des femmes, des personnes âgées et des jeunes cambodgiens qui ont passé la frontière avec les Français. Deux cents autres passeports vierges pouvant sauver autant de vies ont été détruits. Cette responsabilité directe de l’Administration française dans la mort de mon père, trois ans plus tard, m’a empêché de tourner la page de cette histoire pendant des années. Ma mère a aussi énormément souffert de cet évènement.” [In one day, all the inhabitants of our district disappear, obeying the soldiers who send them into the countryside. I remember fifteen days of agonizing waiting at the French Embassy, not knowing what was going to happen to us. I am 13 years old. […] My father remains convinced that the Cambodians will not kill each other forever, that things will work out. Not having French nationality, unlike us, his repatriation is uncertain. Finally, the embassy hands over my father to the Khmer Rouge, and sends us by truck to the border. The French authorities handed over dozens of Cambodians claimed by the Khmer Rouge. What nonsense… Fifty-eight passports were used to protect women, old people and young Cambodians who crossed the border with the French. Two hundred other blank passports that could save as many lives were destroyed. This direct responsibility of the French Administration in the death of my father, three years later, prevented me from turning the page of this story for years. My mother also suffered greatly from this tragedy.”]

Upon completing his graduate and postgraduate studies in Fine Arts and the Science of Art at the Sorbonne University in Paris, Séra developped a parallel career as teacher (at Sorbonne University) and artist : painting, sculpture, drawing, engraving, and graphic novels.

Author of a trilogy of graphic novels reflecting on the Cambodian tragedy : Impasse et rouge (1995, reedition 2003 and 2023), L’eau et la terre (2005, repub. 2023), Lendemains de cendres (2007, repub. 2023), a graphic essay essay about the history of Cambodia, Concombres Amers (2009, in French and Khmer). His published body of work will soon appear in the English language.

With Cambodian artist Vann Nath, Séra held several workshops within the Ateliers de la Mémoire (Memory Workshops), an initiative ot the Bophana Audiovisual Centre engaging young Cambodians into the effort of remembering a past both familiar and still unknown.

In his 2019 thesis, the artist noted that it was in 2008 that he resolved to “join sculpture creation, painting and illustrated books under a single patronym, Séra”. The year before, he had reated an outdoor memorial sculpture for the Cambodian community in the city of Bussy-Saint-Georges, France. This emblematic monument to Those Without Names was installed on a roundabout since renamed : Phnom Penh Place, and in April 2012 the French Institute in Phnom Penh marked its 20th anniversary with an exhibition dedicated to his prolific painted work of Séra. Also in 2012, Séra was named Curriculum Director of the Phare Ponleu Selpak School in Battambang,

He has remarked that the sculptures of Angkor and popular ‘bandes dessinées’ (comics) bought by her mother have both informed his budding artistic character, adding: “Quand je reviens au Cambodge, je né manqué jamais de retourner en immersion dans les temples d’Angkor. Ce retour aux sources de l’art est encore et toujours un moment d’apprentissage des formes et de l’espace. J’y reviens pour voir les pierres et la nature, établir un lien, un dialogue. Ainsi, suivant les saisons, la pierre n’offre pas le même aspect, les mêmes couleurs. Ma peinture se nourrit de l’usure des pierres d’Angkor, quand ma sculpture naît de l’apprentissage de la vie.” [“When I go back to Cambodia, I never fail to immerse myself in the temples of Angkor. This return to the sources of art is still and always a moment of learning about forms and space. I come back to see the stones and nature, to establish a link, a dialogue. Thus, depending on the season, the stone does not offer the same aspect, the same colors. My painting is nourished by the wear of the stones of Angkor , when my sculpture is born from learning about life.”