Le Cambodge,II Les provinces siamoises [Cambodia II: The Siamese Provinces]

by Etienne Aymonier

The Khmer cultural and artistic heritage in the Siamese sphere of influence at the turn of the 20th century.

Type: e-book

Publisher: Leroux, Paris | Vol II of 'Le Cambodge' par Etienne Aymonier, Directeur de l'Ecole Coloniale.

Edition: digital version via bnf.gallica.fr (maps missing)

Published: 1910

Author: Etienne Aymonier

Pages: 480

Language : French

ADB Library Catalog ID: eAYM2

pdf 31.8 MB

Indefatigable explorer, multi-talented researcher, Etienne Aymonier had solid connections with the highest levels of the Kingdom of Siam, including a close friendship to Prince Damrong.

In this detailed books, he asserts himself as a pioneer in the archaeological, architectural and historical fields, for instance with:

- the first identification of Ayuthia as “la ville des frontieres royales de l’ancien Cambodge” [“The Royal Border City”], “its Siamese name being the shortening of the Cambodian “Angkor reach sema”, the latter itself a corruption of the Sanskrit Nagarajasema”, “nowadays Old Korat and not the district capital founded by the Siamese.”

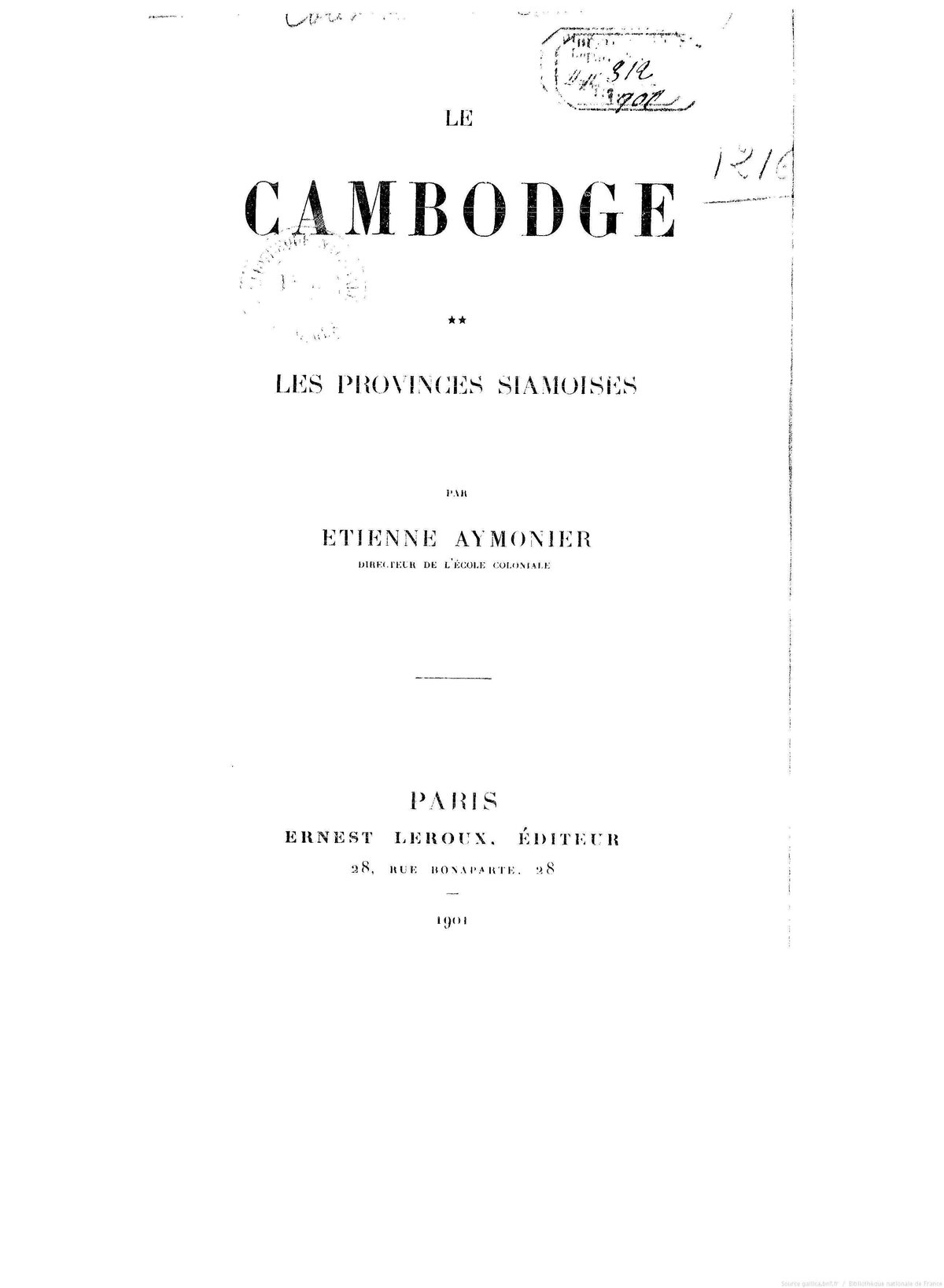

- the first detailed description of the Sukhotai and Phimai sites, with this map of “Phimaie” for instance:

- the first attempt in deciphering and interpreting the Sdok Kak Thom (“The Lake of the Big Reeds”) stele found in the Sisophon region, a major epigraphic discovery.

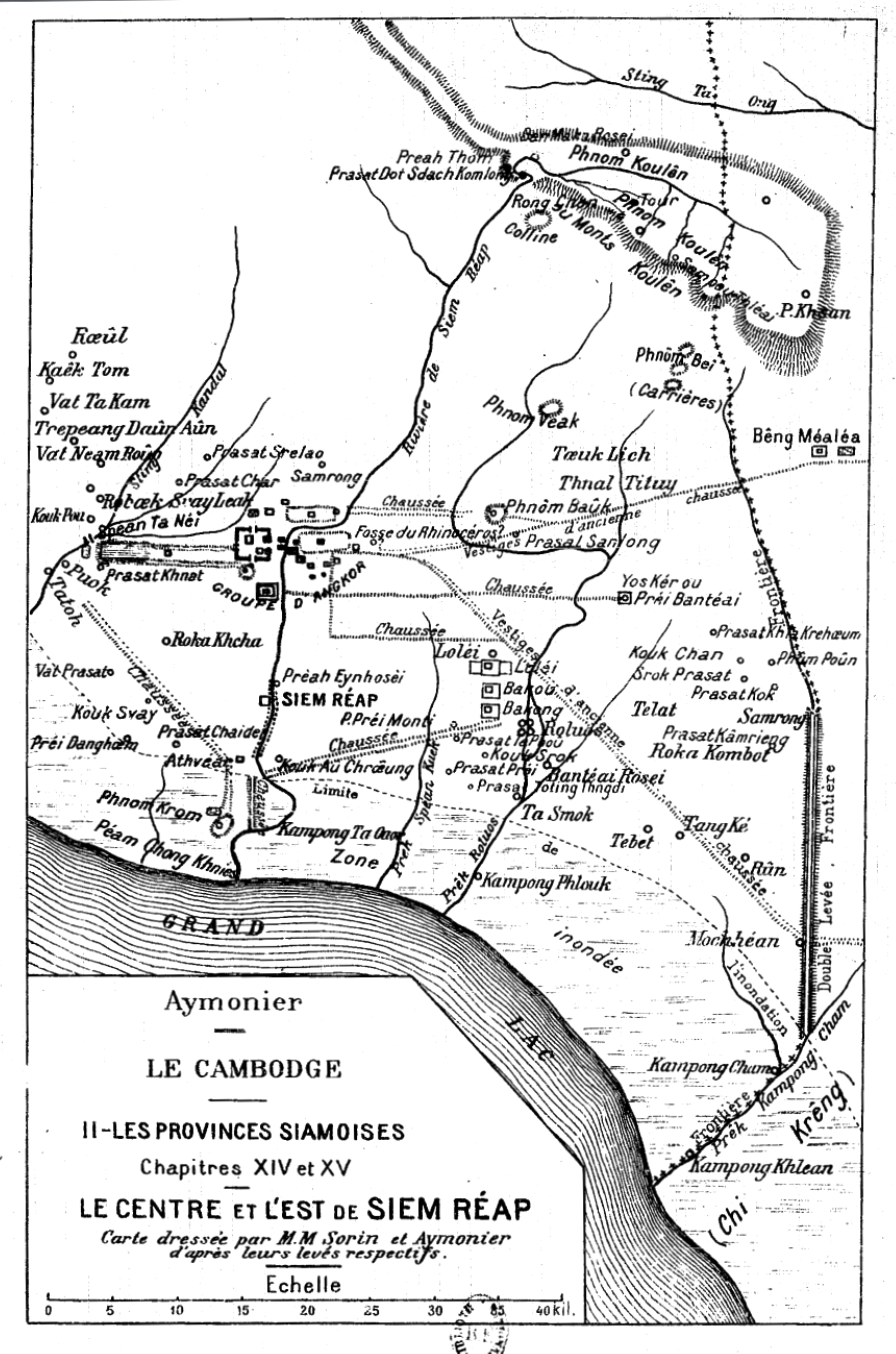

The City of Siem Reap

La ville de Siem Réap. – Les voyageurs qui vicnnent par le Grand Lac et qui désirent visiter les ruines d’Angkor suivent aux hautes eaux les méandres de la rivière dans la jungle et dans la plaine découverte de rizières

qui s’étend au delà pour atteindre la ville de Siem Reap. Ou bien, a l’autre saison, ils prennent une levée ancienne, route de terre plus directe, qui commence au point d’arrêt des barques lors des basses eaux, c’est-à-dire a deux ou trois kilomètres de l’embouchure, qui quitte bientôt la jungle pour traverser la plaine découverte et aboutir au bas de la ville ou le terrain se releve rapidement. Dans l’un et l’autre cas ils laissent sur la gauche le Mont Krom et le monument d’Athvea. Siem Reap “Siamois aplatis, domptes, vaincus” doit tirer ce nom d’une défaite éprouvée par les envahisseurs a l’une de leurs premières invasions chez leurs anciens dominateurs.C’est un centre administratif, commercial et agricole d’une grosse importance, une ravissaute succession de cases cachées sous les orangers et les aréquiers des deux rives. La ville commence à la limite de l’inondation, c’est-à-dire à quelques kilomètres del ajungte du lac et elle s’étend du Sud au Nord sur près d’une lieue de longueur. Les deux rives sont reliées par un pont de bois dont le tablier s’ouvre pour laisser passer les barques au moment de la crue. En saison sèche, de nombreuses norias on grandes roues d’irrigation, de cinq a six mètres de diamètre, aux godets de bambou mues par le couraut de la rivière, légères, bien balancées, versent en abondance aux jardins d’aréquiers l’eau que necessitent ces six mois dépourvus de pluies. A l’Est et a l’Ouest de la ville s’étendent de fertiles rizieres ainsi que des plantations de tabac qui doivent leur reputation et leur richesse a l’excellent engrais du guano de chauve-souris que Ion peut recueillir en abondance dans les ruines de la contrée. La population est khmere mais on y rencontre plusieurs Siamois, Chinois et Annamites.

Quoique le commerce soit actif, on né trouve pas de marché public a Siem Reap. Les edifices reserves au gouvernement et aux services publics sont construits en majorité dans l’intérieur d une vaste citadelle aux remparts bien dessines et coupés de bastions. Les blocs de limonite de cette enceinte proviennent des ruines disseminees dans la region. Elevee, dit-on, vers 1834 par le general siamois Chau Khun Bodin, elle est située sur la rive droite par 13o38’09’‘ 101o32’30’’. E. Moura dit que dans cette citadelle “a peu de distance de la residence du gouverneur est est une superbe idole de Ganesa en gres, de forte dimension, un peu ventrue mais executee de main de maitre. C’est le Neak Ta du lieu.” [p 320]

[The city of Siem Reap. — Travelers who come by the Great Lake and wish to visit the ruins of Angkor follow the meanders of the river in the jungle, and in the open plain of rice fields which extends beyond to reach the city of Siem Reap. Or, at the other season, they take an old levee, a more direct land route, which begins at the stopping point of the boats during low water, that is to say two or three kilometers from the mouth, which soon leaves the jungle to cross the open plain and end at the bottom of the city where the ground rises rapidly. In both cases they leave Phnom Krom and the monument of Athvea on the left. Siem Reap “Siamese flattened, tamed, vanquished” must take this name from a defeat suffered by the invaders at one of their first invasions of their former dominators.

It is an administrative, commercial and agricultural center of great importance, a delightful succession of huts hidden under the orange and areca trees on both banks. The city begins at the flood limit, that is to say a few kilometers from the lake junction and it extends from South to North for nearly a league in length. The two banks are connected by a wooden bridge whose deck opens to let boats pass at the time of flood. In the dry season, numerous norias or large irrigation wheels, five to six meters in diameter, with bamboo buckets moved by the current of the river, light, well balanced, pour abundantly into the areca gardens the water required for these six months without rain. To the east and west of the city lie fertile rice fields and tobacco plantations that owe their reputation and wealth to the excellent fertilizer of bat guano that can be collected in abundance in the ruins of the region. The population is Khmer but there are several Siamese, Chinese and Annamites.

Although trade is active, there is no public market in Siem Reap. The buildings reserved for the government and public services are built mainly inside a vast citadel with well-designed ramparts and cut by bastions. The blocks of limonite of this enclosure come from the ruins scattered in the region. Erected, it is said, around 1834 by the Siamese general Chau Khun Bodin, it is located on the right bank at 13o38’09’‘ 101o32’30’’. E. Moura says that in this citadel “a short distance from the governor’s residence is a superb idol of Ganesa in sandstone, of large size, a little pot-bellied yet executed by a master’s hand. It is the Neak Ta of the place.”

Read the ebook

This book has been translated into English: Khmer heritage in the old Siamese provinces of Cambodia : with special emphasis on temples, inscriptions, and etymology (trans. by Walter E. J. Tips, Lotus Press, Bangkok, 1999, 302 p)

Tags: Siam, Khmer Empire, archaeology, Khmer arts, Sisophon, Bassac, Battambang, epigraphy, Siem Reap, Siem Reap River

About the Author

Etienne Aymonier

Étienne François Aymonier (26 Feb 1844, Le Chatelard, France – 21 Jan 1929, Paris), French naval officer, colonial administrator, linguist and explorer, was the first scientist to extensively survey the ruins and inscriptions of the Khmer empire in today’s Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and southern Vietnam, as well as the Cham civilization. Le Cambodge (three volumes published) from 1900 to 1904, remains to these days an important source for geographers, historians and epigraphists.

First director of the École Coloniale — where he also taught Khmer language since his retirement in 1905 -, he assembled a large collection of Khmer sculpture later housed in the Guimet Museum, Paris. They were major artworks that completed his stampings of Khmer and Cham inscriptions, yet in 1910 George Coedès complained they had not been properly labeled and sourced.

Author of a Dictionary of Cham-French (with Antoine Cabaton), a Khmer-French Lexicon and a Dictionary of Khmer, as well as a collection of Khmer texts, Textes khmers (1885), he was recognized as one of the first epigraphists working intensively in Cambodia, relying for the Sanskrit parts to the expertise of his friends Abel Bergaigne, Auguste Barth and Sylvain Lévi. In 1878, he transcribed the “Poem of Angkor Wat” (ល្បើកអង្គរវត្ត Lpoek Angkor Vat) in modern Khmer.

Fresh from St. Cyr Army School, he started as sublieutenant in Cochinchina in 1869 and, as adjunct to French Protectorate Representative Paul-Louis-Félix Philastre, prospected Kompong Thom province for his first officious exploration in 1876. While perfecting his knowledge of the Khmer language, he replaced Jean Moura as Protectorate plenipotenriary representative from 1 Jan 1879 to 10 May 1881, a function first occupied by Ernest Doudart de Lagree from April 1863 to July 1866. Indefatigable traveler, he crisscrossed Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, from 1881 to 1885, gathering essential information.

While Aymonier trained numerous local volunteers (Cambodian, Laotian and Vietnamese) to mastering archaeological and epigraphic techniques, and acknowleged their contribution in his writings — paying homage to “a collaborator named An, in particular” (Introduction to Le Camboge, I, 1900), he somehow remained a maverick in the field of Khmer and Cham studies. According to Cristina Cramerotti (trad. Jennifer Donnelly), author of Collectionneurs, collecteurs et marchands d’art asiatique en France 1700 – 1939 INHA), “neither the “field” scientist nor the administrator enjoyed unanimous support whether in academic circles or the hierarchy. While he contributed to bringing the future École française d’Extrême-Orient to the baptismal font, a bitter controversy over Funan pitted him against Paul Pelliot (1878−1945) who reproached him for his dangerous individualism in scientific matters [see details of their confrontation in the latter’s ADB biographical note]. His self-taught side bothered scholars: his candidacy as a free member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, which had once praised him, was refused twice. He developed some resentment. In addition, his character, sometimes described as “rough”, his independence of mind, and the proposals for reform of the colonial administration, expressed in a rather abrupt way, ended up doing him a disservice.”

In his 1929 [rather acrimonious] obituary, George Coedès wrote

C’est l’un de ces articles [Aymonier’s] relatif au Fou-nan qui déclencha une polémique dont le résultat le plus triste fut d’aliéner à l’Ecole Française la sympathie d’un homme qui aurait eu tant de raisons de travailler en étroite collaboration avec elle, et qui, dans l’introduction de son Cambodge, saluait «la création de cette Ecole d’Extrême-Orient qui est un résultat très direct de ma mission archéologique qu’elle doit continuer dans des conditions infiniment plus favorables à tous les points de vue». Il avait commis l’imprudence, lui, qui n’avait aucune connaissance sinologique, de s’en prendre aux sinologues: genus irritabile ! La riposte de M. Pelliot lui causa une blessure d’amour-propre qui empoisonna les vingt-cinq dernières années de sa vie. et qu’il ressentait encore à la veille de sa mort. Sous le prétexte de mettre l’histoire ancienne du Cambodge à la portés de tous, ses deux derniers opuscules, oeuvres séniles sur lesquelles il serait cruel d’insister, n’eurent d’autre objet que de défendre une cause depuis longtemps perdue et classée. Heureusement, le travail de collaboration entre lui et M. Cabaton, qui devait aboutir en 1906 à la publication du Dictionnaire cam-français, était déjà presque terminé en 1904, et l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient a ainsi la satisfaction de pouvoir inscrire le nom d’Aymonier parmi ceux de ses collaborateurs. Lorsque le progrès des études aura relégué ses travaux au nombre des ouvrages qui n’ont plus qu’un intérêt bibliographique, l’oeuvre accomplie pendant sa mission de 1882 – 1885 qui fonda l’épigraphie khmère sur une base solide et ressuscita les Chams ignorés avant lui, cette oeuvre subsistera comme un témoignage de son labeur et de son dévouement à la science, et suffira à assurer à son nom une place éminente dans l’histoire des études indochinoises.

[It was one of these articles [Aymonier’s] relating to Fou-nan which triggered a controversy whose saddest result was to alienate from the French School the sympathy of a man who would have had so many reasons to work in close collaboration with the School, and who, in the introduction to his Cambodia, welcomed “the creation of this Far Eastern School, a very direct result of my archaeological mission which it must continue in infinitely more favorable conditions from all points of view”. He, who had no sinological knowledge, had been imprudent in attacking the sinologists: genus irritabile! Mr. Pelliot’s response caused an injury to his self-esteem which poisoned the last twenty-five years of his life, and which he still felt on the eve of his death. Under the pretext of making the ancient history of Cambodia accessible to all, his last two pamphlets [Un aperçu de l’histoire du Cambodge, Paris, 1918, and Histoire de l’ancien Cambodge, Strasbourg, nd] senile works on which it would be cruel to dwell, had no other purpose than to defend a cause long lost and cold. Fortunately, the collaborative work between him and Mr. Cabaton, which was to lead in 1906 to the publication of the Dictionnaire cam-français, was already almost finished in 1904, and EFEO thus has the satisfaction of being able to include the name of Aymonier among those of his collaborators. When the progress of studies will have relegated his works to the number of works which no longer have more than a bibliographical interest, the work accomplished during his mission of 1882 – 1885, which founded Khmer epigraphy on a solid basis and resurrected the ignored Chams before him, this work will remain as a testimony to his work and his dedication to science, and will be enough to ensure his name an eminent place in the history of Indochinese studies.

Tough love.

Publications (publications added from G. Coedès and ADB research)

- “Les Monuments du Cambodge meridional”, Revue orientale et americaine, ed. Leon de Rosny, t. 1 new series, 1876.

- “Excursion dans le Cambodge central”, Bulletin de la Société de géographie (BSG), 1882, pp. 656 – 663.

- “Critique du “Royaume du Cambodge” de M. Moura”, Excursions et Reconnaissances (E&R), XVI, 1883, pp. 207 – 220.

- “Exploration au Cambodge, lettre de Saigon du 11 août 1883”, compte-rendu des séances de la SG, 9 Nov. 1883, pp. 486 – 490.

- “Notes sur les coutumes et croyances superstitieuses des Cambodgiens”, E&R, XVI, 1883, pp. 133 – 206.

- “Quelques notions sur les inscriptions en vieux khmer”, Journal Asiatique (JA), 1883 (1), pp 441 – 505; (2), pp. 199 – 228.

- “L’épigraphie kambodjienne”, E&R, XX, 1884, pp. 253 – 296.

- “Lettre sur son voyage au Binh-Thuan, adressée à M. le Gouverneur de la Cochinchine. E&R, XXII, 1885, pp. 247 – 254.

- “Les Chams”, Revue d’ethnographie (RE), IV, 1885, pp. 158 – 160.

- “Notes sur le Laos. Région du Sud-Est, détails géographiques”, E&R, XX, 1884, pp. 35 – 386; XXI, 1885, pp. 5 – 130; XXII, 1885, pp. 255 – 347.

- “Notes sur l’Annam. I. Le Binh-Thuan. II, Le Khanh-Hoa”, E&R, XXIV, 1885, pp, 199 – 340; XXVI, 1886, pp. 179 – 218; XXVII, 1886, pp. 5 – 29.

- “Nos transcriptions. Étude sur les systèmes d’écriture en caractères européens adoptés en Cochinchine française”, E&R, XXVII, 1886, pp. 31 – 89.

- “Grammaire de la langue chame”, E&R, XXXI, 1889, pp. 5 – 92.

- “Annam et Tonkin. Colonies françaises et Pays de protectorat à l’Exposition uni. de 1889”, Guide, pp. 27 – 37.

- “Légendes historiques des Chames”, E&R, XXXII, 1890, pp. 145 – 206.

- La langue française et l’enseignement en Indo-Chine, Paris, 1890, in‑8°.

- “La langue française en Indo-Chine”, Revue scientifique (RS)., 1891.

- “Les Tchames et leurs religions”, Revue d’histoire des religions (RHR), 189 1, XXIV, pp. 187 – 237; 261 – 315.

- “Première étude sur les inscriptions tchames”, JA, 1891 (1), p. 5 – 186.

- Communication sur la fondation de la dynastie cambodgienne, compte-rendu Academie des Inscriptions et belles lettres (AIBL), 1891, p. 429 – 430.

- “Une mission en Indo-Chine. Relation sommaire”, BSG, 1892, pp. 216 – 249, ЗЗ9 – 374.

- “The history of Tchampa (The Cyamba of Marco Polo, now Annam or Cochin-China)”, publication of the 9t International Congress of Orientalists, London., VI, 1893, p. 140 and 365.

- “Sommaire des travaux relatifs à l’Inio-Chine pendant la période 1886 – 1891, ibid, 1893.

- “Découvertes or héologiques de M. Camille Paris dans la province de Quang-nam. Inscriptions découvertes par M. C. Paris au Tchampa”, Bulletin de Géographie, Histoire et Descriptions (BGHD), 1896, pp. 92 – 95; pp 329 – 330.

- “Rapport sommaire sur les inscriptions du Tchampa, découvertes et estampées par les soins de M. Camille Paris”, JA., 1896 (1), pp. 146 – 151.

- “Note sur les derniers envois de M. C. Paris, chargé d’une mission en Annam. BGHD, 1897, pp. 389 – 390.

- “Rapport sur le dernier mémoire de M. Camille Paris”, BGHD, 1898, pp. 247 – 249.

- Mission Etienne Aymonier. Voyage dans le Laos, Annuaire Musée Guimet, Bibliotheque d’études, V‑VI. Paris, 1895 – 1897, 2 vol. in‑8°.

- “Le Cambodge et ses monuments. La province de Ba Phnom”, JA, 1897 (1), pp. 185 – 222.

- “Le Cambodge et ses monuments. Koh Kêr, Phnom Sandak, Phnom Prah Vihear”, RHR, XXXVI, 1897, pp. 20 – 54.

- “Découvertes épigraphiques de M. C[amille] Paris, JA., 1898 (2), pp. 359 – 360.

- “Le roi Yašovarman”,Actes du XIe Congres international des orientalistes, 2e section (langues et archéologie de l’Extreme-Orient, p. 191. Paris, 1898.

- “Communication sur une inscription chame trouvée par le P. Durand à Kon Tra”, JA, 1899 (2), pp. 544 – 545.

- “Les inscriptions du Preah Peân (Angkor Vat)”, JA, 1899 (2), pp. 493 – 529.

- “Les inscriptions du Bakan et la grande inscription d’Angkor Vat”, JA,1900 (1), pp. 143 – 175.

- “La stèle de Sdok Kâk Thom”, JA, 1901 (1), pp. 5 – 52.

- “Le Founan”. JA, 1903 (1), pp. 109 – 150.

- “Le Siam ancien”, JA., 1903 (1), pp. 185 – 239.

- “Nouvelles observations sur le Founan”, JA, 1903 (2), pp. 333 – 341.

- “Les fondateurs d’Angkor Vat”, Album Kern, Leide, 1903, p 165.

- Le Cambodge, Paris, 1900 – 1904, 3 vol.

- “Identification de noms de lieux portés sur les cartes publiées par M. Marcel dans le Siam ancien de M. Fournereau”, BGHD, 1905, pp. 43 – 44.

- [with A. Cabaton], Dictionnaire cam-français, PEFEO, vol. VII, Paris, 1906, in‑8°.

- “L’inscription came de Po Sah”, BCAI, 1911, pp. 13 – 19.

- Un aperçu de l’histoire du Cambodge, Paris, 1918, in-12.

- Histoire de l’ancien Cambodge, Strasbourg, s. d.

[Numerous pieces brought from Cambodia by Aymonier were exhibited at the Musée Guimet “Exposition des résultats des voyages et explorations scientifiques en Asie : Religions, arts, archéologie et ethnographie”, Paris, 1893.]