Ernest Doudart de Lagrée

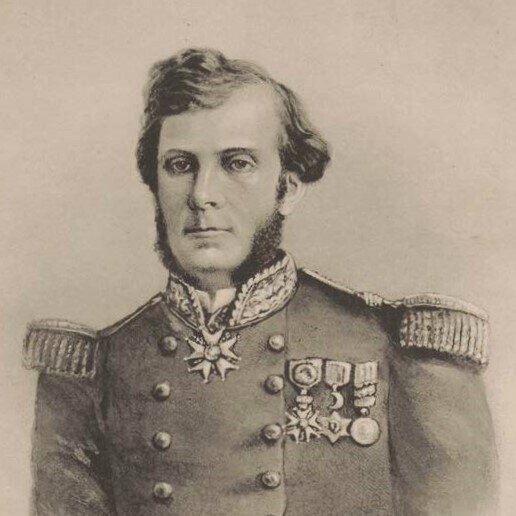

Ernest Marie Louis de Gonzague Doudart (or Doudard [1]) de Lagrée [after 1862 Doudart de La Grée, the original spelling of his ancestors’ name] (31 March 1823, Saint-Vincent-de-Mercuze, France — 12 March 1868 à Tong-Tchouen [2], Yunnan) was a French Navy officer, explorer, archaeologist and numismatist who established the first official contacts with King Norodom I as Captain of the Gia-dinh frigate and under the instructions of Admiral de la Grandiere in August 1863, and led the Commission d’exploration du Mekong from 1866 to his death in March 1868 from a chronic larynx infection.

In 1864, he discovered numerous manuscripts in Oudong, the royal capital city at that time, including parts of the Royal Chronicle of Cambodia, which he translated into French with the help of Cambodian interpreters — among them Col de Monteiro, Alexis Om, who had grown up in Singapore and was fluent in Khmer, Vietnamese, English, with some command of the French language– and A‑Chhun, his “favorite student”– and monks, while his mecanician Laederich took down his words on paper.

At that time, Doudart de Lagree was de facto the representative of French interests in Cambodia, the French envoy closest to King Norodom, his “confident, advisor and political tutor”, according to contemporary biographers, and he served as the first “Representant du Protectorat” from April 1863 to July 1866. However, military career and official responsibilities attracted him much less than his scientific interest in Cambodia which he described as follows in one of this numerous letters to his friends and siblings:

Tout ce pays est beau, mais il est ruiné par des siècles de guerres civiles et étrangères. Resserré depuis longtemps entre deux empires plus puissants que lui, le Siam et la Cochinchine, alternativement conquis dix fois par chacun d’eux, il allait dIsparaître lorsque nous sommes arrivés. Les habitants sont bons et ouverts. Depuis plusieurs siècles il y a des chrétiens ici, et jamais aucun d’eux n’a été inquiété. Les Cambodgiens tiennent beaucoup de la race hindoue, nullement de la chinoise race d’où proviennent, au contraire, les Annamites : aussi né sont-ils ni rusés ni voleurs comme ceux-ci. Mais comme ils sont timides! et paresseux! Leur langue, je commence à la parler tant bien que mal. On parvient en quelles jours à se faire comprendre, mais il faut de longues années pour parler bien. […] La vie est à bon marché au delà de toute expression lorsqu’on n’a pas de goûts civilisés à satisfaire, le poisson se donne, les poules sont à trois sous et les boeufs a 10 ou 12 francs! Aussi je nourris mon équipage de vingt-huit hommes avec 3 ou 4 francs par jour. Mais à moi seul combien je dépense davantage ! Qu’y faire? Je né puis pas né pas aimer le fromage, et quand j’en fais venir, je le paye 8 francs la livre, même le plus humble gruyère ! C’est désolant. Puis j’aime les olives (on n’est pas parfait), et les pommes de terre. Si je tenais un gratin, un de NOS gratins! [gratin dauphinois] Mais sachons dissimuler nos passions et né nous compromettons pas par de trop naives expansions…”

[The whole country is beautiful, but it is ruined by centuries of civil and foreign wars. Squeezed for a long time between two empires more powerful than itself, Siam and Cochinchina, alternately conquered ten times by each of them, it was about to disappear when we arrived. The locals are good and open people. For several centuries there have been Christians here, and none of them has ever been worried. The Cambodians have a lot of the Hindu race, in no way of the Chinese race from which, on the contrary, the Annamites come: so they are neither cunning nor thieves like the latter. But how shy they are! and lazy! Their language, I am starting to speak it as best I can. It takes a few days to make yourself understood, but it takes many years to speak it well. […] Life is cheap beyond expression when one has no civilized tastes to satisfy. Fish is a steal, chickens cost three sous, oxen 10 or 12 francs! So I feed my crew of twenty-eight men with 3 or 4 francs per day. But on my own, how much more I spend! What to do there? I can’t not love cheese, and when I order it, I pay 8 francs per pound for it, even the humblest Gruyère! It’s saddening. Then I like olives (nobody’s perfect), and potatoes. If I could have a gratin, one of OUR gratins! [gratin dauphinois] But let us learn to conceal our passions, and not compromise ourselves by too naïve outpourings…”] (Explorations et Missions, p 405)

On June 6, 1866, the CEM (Mekong Exploration Commission left Saigon for Kompong Luong in Cambodia, reaching Angkor on August 24. Francis Garnier, Louis Delaporte (drawings, cartography and logistics), Louis de Carné (representative of the French Foreign Ministry), Dr. Etienne Joubert and Dr. Clovis Thorel were part of an expedition, briefly joined by photographer Emile Gsell — organizational details in Felix Julien’s Lettres d’un precurseur — aimed at evaluating the navigability of the Mekong up river. In fact, it was Doudart de Lagree, head of the Commission, who insisted for a detour at Angkor, as he had already briefly visited the Khmer ruins in November 1863. An archaeologist in the making — he had always been fascinated by the Greek and Roman ruins –, he felt that the remains of the Khmer ancient civilization were essential to understand modern Cambodia and the whole region. As his biographer Claude-Arthur-Anatole Bonamy de Villermeuil (1826−1908) was to remark: “Certes, Doudart de Lagrée né vit, dans cette profusion d’ornements et de sculptures décoratives, que l’expression de la foi bouddhique. C’est, en réalité, Bastian qui, le premier, a reconnu dans les bas-reliefs d’Angkor vat une mise en scène des poèmes homériques de la religion de Brahma. Or, Bastian a visité Angkor à l’époque du second voyage de Lagrée, et seulement après. En résumé, la curiosité publique a été mise en éveil par Mouhot; mais l’élan vers de nouvelles découvertes fut donné par celles de Lagrée; l’aspiration vers une solution de l’inconnu auquel on venait de se heurter, prit une forme par ses études historiques et ses travaux épigraphiques et archéologiques. Tel est le véritable point de départ de l’archéologie du Cambodge.” [“Certainly, Doudart de Lagrée only saw the expression of the Buddhist faith in this profusion of ornaments and decorative sculptures. Bastian was in fact the first to recognize in the bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat a staging of the Homeric poems of the religion of Brahma. However, Bastian visited Angkor at the time of Lagrée’s second trip, and only afterward. In summary, public curiosity was aroused by Mouhot; but the impetus towards new discoveries was given by those of Lagrée; the aspiration towards a solution to the unknown which we had just encountered, took shape through his historical studies and his epigraphic and archaeological work. This is the true starting point of the archeology of Cambodia.”

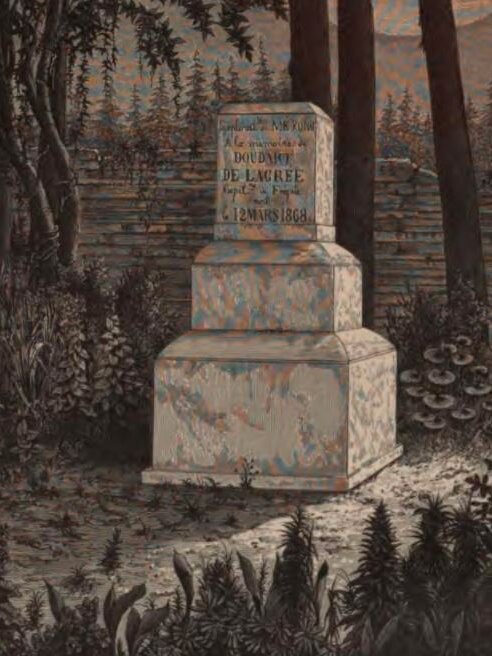

After Stung Treng, they reached Khon in modern Laos on Aug 18, 1866, Luang Prabang on April 29, 1867, the expedition was close to the banks of the Yangtze-kiang, the “Blue River” de Lagree had dreamt of seeing, when a chronic illness combined with an exhausting expedition took his life. His companions buried him temporarily before his remains was transfered to Saigon, and Dr. Joubert improvised a lead box containing his heart, to be sent to France for a Catholic burial in St Vincent-de-Mercuze, France.

Declining to fulfill the deceased’s last wishes — he wanted all his manuscripts and notes to be burned, arguing that “a man’s life work can be completed only by himself” -, the same Joubert sent them to France in a wooden crate in the custody of sailor Mouello, kept by his brothers Jules and Casimir Doudart de Lagréem, and his sister-in-law Mme Jules de Lagrée. The eldest brother, after consultating scientists, decided in 1875 to authorize their publication. They were sorted out and edited by his closest friends: De Villermeuil, Félix Julien, and Louis André Alfred Nugues Durand d´Auxy (1820−1886), who was in possession of part of his correspondence (1852−1867) and of another crate, sent to him by de Lagrée and containing his notes for a book on Cambodia he planned to publish. These papers, however, have disappeared.

In Saigon, a street name and a monument were dedicated to his memory. During the French protectorate, Norodom Boulevard (មហាវិថីព្រះនរោត្តម) in contemporary Phnom Penh was named Boulevard Doudart de Lagrée.

[1] On his graduation certificate at Ecole Polytechnique (Promotion 1842), his name is spelled Doudard with D.

[2] French transcription [the English one was T’ung-ch’uan] for Dongchuan (东川), near Kumning, capital of the Yunnan Province, China.