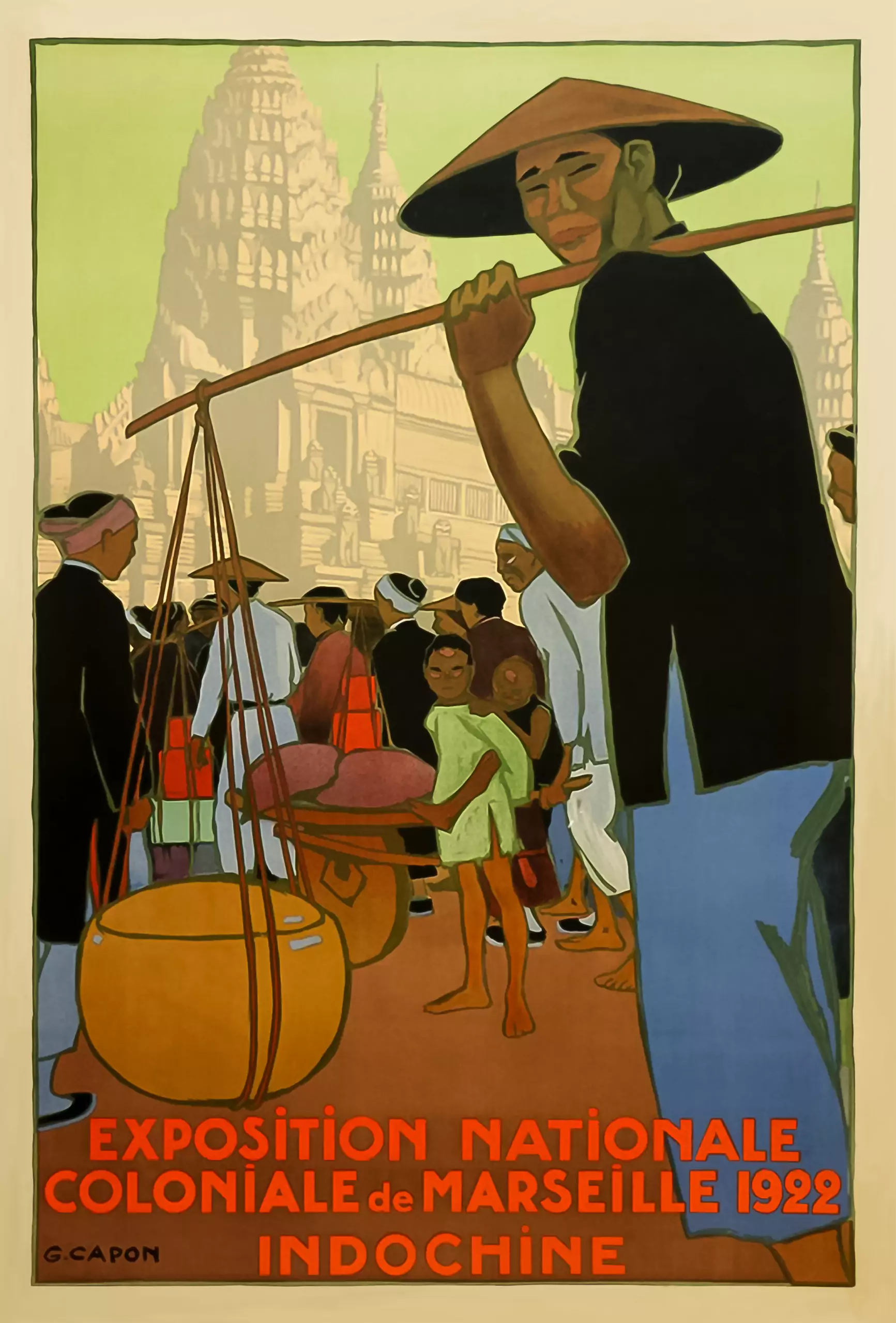

L'Indochine, Exposition nationale coloniale de Marseille, 1922 [1922 Marseille National-Colonial Exhibition: Indochina]

by Pierre Guesde

The 1922 Colonial Exhibition in Marseille, France, with Angkor Wat tower pinnacles, Khmer ancient sculptures and live dancers starring.

- Publisher

- in L'Exposition nationale coloniale de Marseille décrite par ses auteurs, Commission générale de l'exposition, Marseille, 1923, p 79-99

- Edition

- digital version via gallica.bnf.fr

- Published

- 1923

- Author

- Pierre Guesde

- Pages

- 20

- Language

- French

pdf 5.7 MB

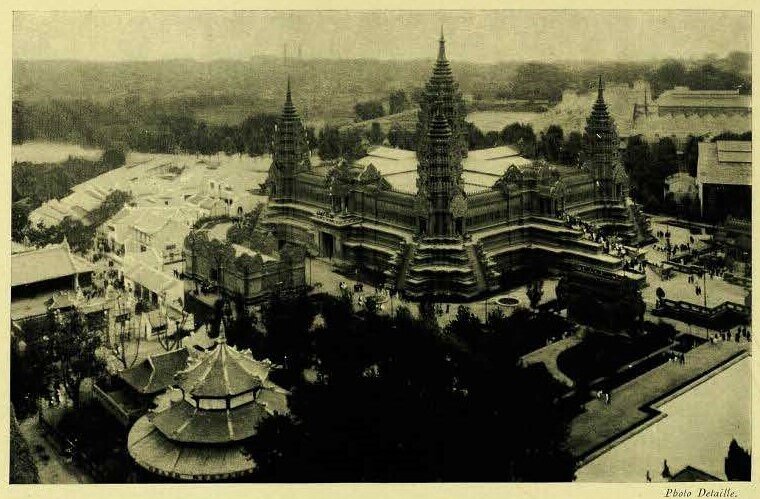

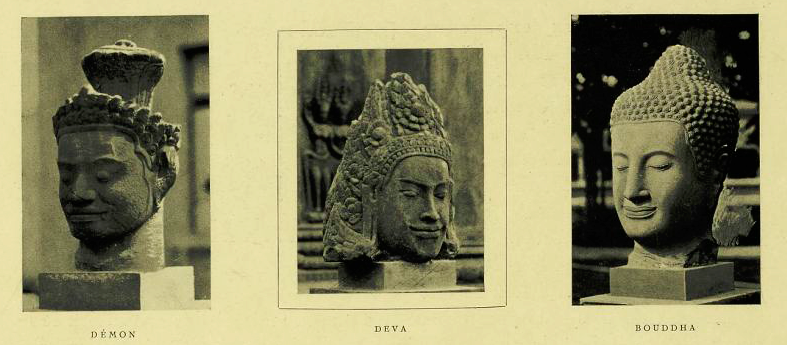

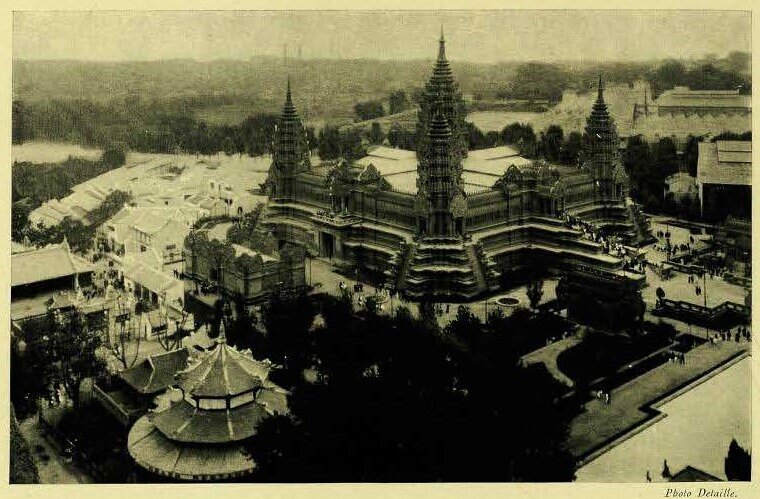

Less spectacular than the earlier Expositions Universelles in Paris, the Marseille 1922 “national-colonial” exhibition was nevertheless a stimulating test bench for architects, designers, artists in charge of the Grand Palais, a 70-meter square replica of Angkor Wat — not an attempt at mimicking the actual temple, but a free reinterpretation of it with eight monumental stairways designed to let the public access the exhibition halls inside — that was the core of the “Indochina” section. The work of chief architect Auguste Delaval and engineers Blanchard and Molinari — who also built replicas of two Angkor Wat libraries, were decorated by large painted panels done by visual artist Marie-Antoinette Boullard (soon Boullard-Devé) — with other frescoes by Marliave -, by plasterers Aubarlet and Laurent for the Angkor reliefs mouldings, and by real Khmer sculptures brought to France by EFEO member Victor Goloubew — most of them ended up in the collection of Paris Guimet Museum. Even elephants were brought from Cambodia.

The author of the chapter on Indochina, Pierre Guesde, was also to act as General Commissionner for Indochina at the International Colonial Exhibition in May-Sept. 1931, at Vincennes, near Paris, which attracted some nine million visitors and represented the apex of the French colonial idea of “mission civilisatrice”. One can consider Marseilles 1922 as the ‘dress rehearsal’ for Vincennes 1931.

According to Michael Falser, Beaux-Arts-trained — and future architect of important buildings in French Indochina, including Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) Museum of History — Auguste Delaval (18 March 1875, Nevers — 1962, Hennebont, France) had exchanged correspondence witht the first Conservator of Angkor, Jean Commaille, since 1915, as he was researching his project of a nearly 1:1‑scaled replica of Angkor Wat as the star pavilion during the Exposition nationale coloniale in Marseille initially planned for 1916 but postponed to 1922): “He requested advice on ‘how to build the tower pinnacles’ in an archaeologically correct manner so far from the ruined original. Commaille sent him his sketched proposal of such an architectural element, which he himself had not yet reconstructed at Angkor proper. As a result of this unique contact situation, Commaille’s reconstruction sketch was not carried out first at the original site; instead, its aesthetic effect was first tested in realiter in France. A few years after 1922, the full 1:1‑scale, spotless and ageless replica of Angkor Wat – arguably the largest replica ever made of non-European architecture on the European continent – materialised in the famous 1931 International Colonial Exhibition in Paris.” [Angkor Wat — A Transcultural History of Heritage, Vol 2: Angkor in Cambodia. From Jungle Find to Global Icon, DeGruyter, 2020, p 387). Note that both Commaille and Delaval were dedicated amateur painters, both favoring watercolor.

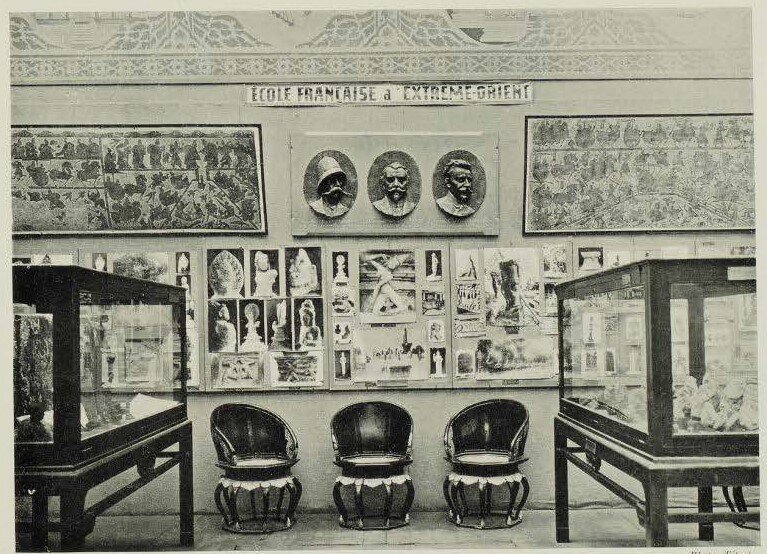

Marseille 1922 was also the first time in France that the Ecole Francaise d’Extrême-Orient had its own exhibition hall, along with maps and charts from the Service géographique de l’Indochine.

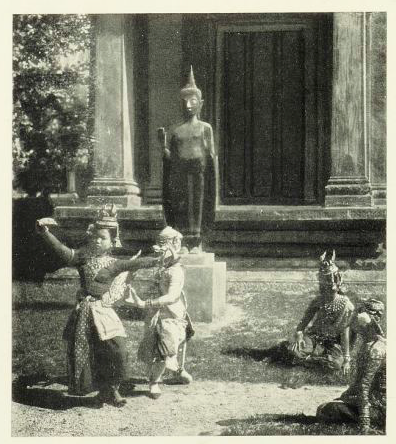

World War I had raged on for four years between the Royal Ballet of Cambodia “ravishing dancers“ ‘ first visit to Marseilles in 1906 — the one Auguste Rodin came to witness and marvel at — and this one, but once again the public interest was aroused and the “gracious Khmer ballerinas” gave several performances. The prima ballerina seems to have been Ith, later photographed by George Groslier during rehearsals at the Royal Palace and Albert Sarraut (now National Museum of Cambodia) in Phnom Penh.

Elsewhere in this commemorative book, it was noted that

Les danseuses cambodgiennes, que le Commissariat Général de l’Indochine produisait à intervalles rapprochés

devant un public d’élite, dans son délicieux pavillon du boulevard Michelet, se firent applaudir à plusieurs

reprises par le grand public du Parc et dans la salle des fêtes du Grand Palais. [The Cambodian dancers, whom the General Commissariat of Indochina produced at short intervals in front of an elite audience in its delightful pavilion on Boulevard Michelet, were applauded several times by the general public in the Park and in the ballroom of the Grand Palais.] [p 299]

Tags: Colonial Exhibitions, Angkor Wat replicas, Royal Ballet of Cambodia, dancers, Cambodian dance, architecture

About the Author

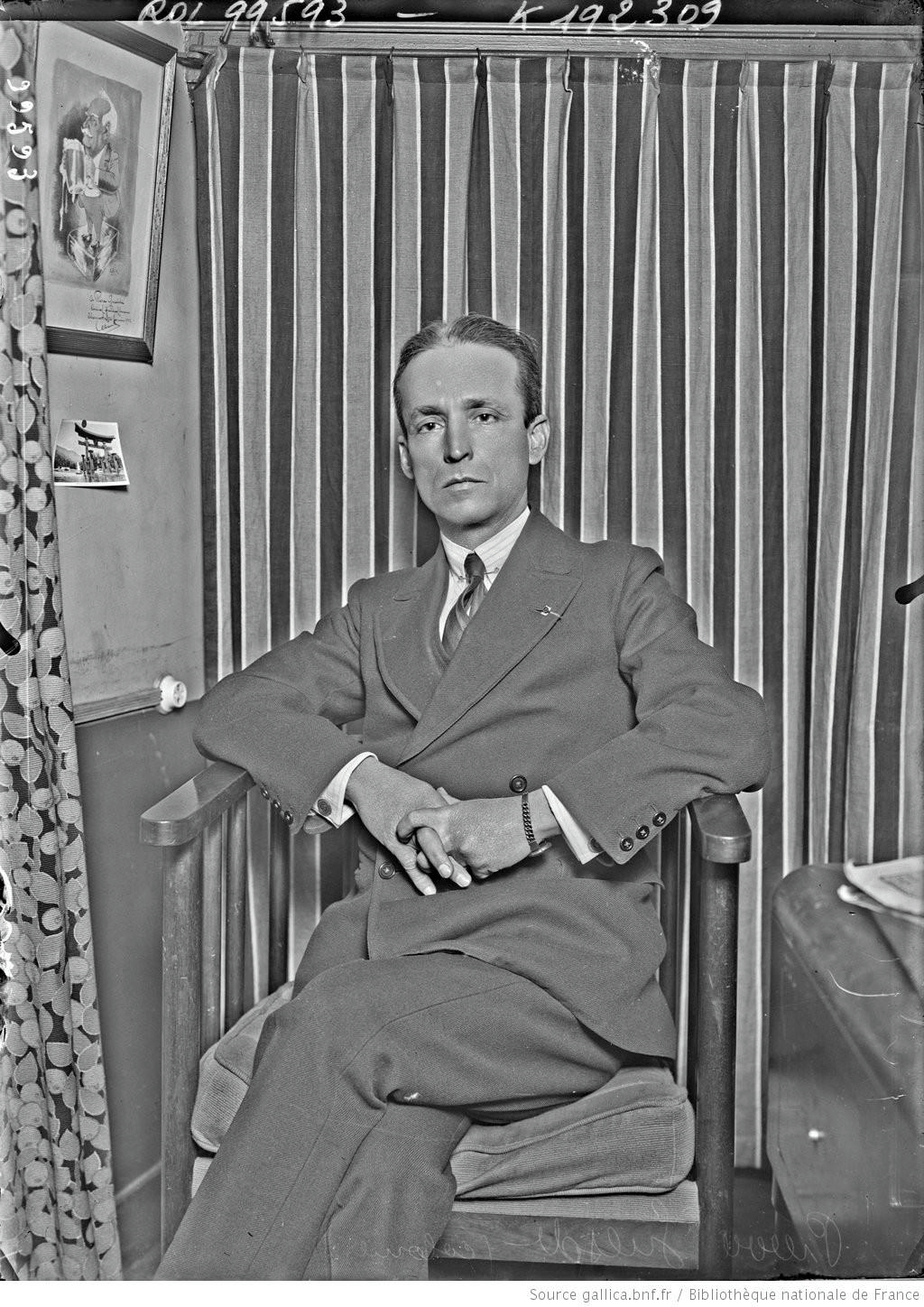

Pierre Guesde

Pierre Mathieu Théodore Guesde (9 May 1870, Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, French Caribbean=) — 1955) was a French colonial administrator from 1896 to 1914, Resident-superieur of Indochina for a few months in 1914, and Commissioner for Indochina at the 1922 (initially scheduled for 1916) Marseille National Colonial Exhibition, at the 1924 Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris, and at the spectacular 1931 Vincennes International Colonial Exhibition. After retiring from public service (and even before), he was an ubiquitous businessman, sitting at the board of more than 20 companies active in France and the colonies, and in Switzerland.

He was also the French chief official in Ha-tien (Cochinchina, now in Kiên Giang Province, Vietnam) in 1906, head of the Interpreters Bureau under Resident-Superieur Boulloche’s supervision since 1901, accreditated interpreter to King Sisowath and, according to La Depeche coloniale (4 Nov. 1911), “il fut chargé en raison de ses qualites de la délicate mission de ramener de Singapore, où il s’était réfugié à la suite des événements que l’on sait, le prince Yucanthor.” [“due to his merits he was entrusted with the sensitive mission of bringing back to Cambodia Prince Yukhantor, who had sought refuge in Singapore after some well-known developments.”][1].Based in Pursat in 1907 – 8, he contributed to the outlying of the new borders between Siam and Cambodia within the negotiations for the retrocession of Battambang and Siem Reap provinces.

Back in France, he was a professor of Cambodian language (Khmer) at Ecole des langues orientales vivantes, secretary-treasurer of the Société d’Angkor pour la conservation des monuments anciens de l’Indochine, adjunct-private secretary of the Minister of Colonies Albert Lebrun (soon-to-be French Republic President) from 1909 to 1914, and private secretary of the Minister of Public Education Albert Sarraut in 1916. After World War I, during which he fought in Verdun, he pursued his career in both ministries, retiring in 1923 but still taking care of the Vincennes 1931 Colonial Exhibition.

Pierre Guesde’s parents were Louis Athanase Mathieu Guesde (1844−1924), a pharmacist-archaeologist who collected stone hatchets made by native Guadeloupe people, and Marie Elizabeth Nelly Botreau Roussel de Bonnetere (ca 1846-ca 1926). When living in Phnom Penh, he had a daughter with Cambodian Neang Molis (named Anne-Marie Guesde in administrative papers), Nelly Pierrette (1898−1965), who later became French-Cambodian writer Makhali-Phal. From that union was also born Louis Pierre Roger Guesde (1900−1969), who moved to Tananarive, Madagascar, in the 1930s. On 17 September 1906 , in Geneva (Switzerland), Pierre Guesde married Marguerite (Margherete) Linder, the daughter of Austrian economist Maurice Linder, and they had two children: Henri Mathieu Théodore Maurice George Guesde (1910−1933), and Marie Louise Élisabeth-Lily Guesde (1908−1997), who married Polytechnician André Widhoff in 1935.

The website Entreprises Coloniales (27 Oct. 2016, updated 4 Apr. 2023) has drawn the impressive list of companies with which Guesde worked during his business career, mostly as a member of the Board of Directors:

- Société d’études pour la culture du coton en Indochine;

- S.A. Le Contrôle Technique, Groupement pour la réception des matériaux et machines, la surveillance des fabrications et des constructions (Aug 1924);

- within the Estier-Vigne corporation: administrator of Banque française du Maroc (Oct 1923), Mines de zinc de Chodon, along with Joseph Vigne (same year), Est-Asiatique français (March 1924) becoming Compagnie asiatique et africaine (together with son-in-law Andre Widhoff, who was on the board of Compagnie internationale des Wagons-lits, and several Africa-based commercial operations), Compagnie indochinoise de navigation (1924), Compagnie asiatique de navigation (1938) with Georges Hecquet;

- within SICAF: Thés de l’Indochine (March 1924), Compagnie des Grands Lacs de l’Indochine, Hévéas de la Souchère, Cafés de l’Indochine, Plantations d’hévéas de Chalang (Sept 1927), Plantations d’hévéas de Prek-Chlong, Plantations indochinoises de thé (1933);

- with SFFC (Octave Homberg): Salines de Djibouti (July 1924), Crédit foncier de l’Indochine (along with Homberg and Joseph Vigne), Crédit hypothécaire de l’Indochine (1933), Crédit mobilier indochinois (pawnshops, Oct. 1935), Tramways du Tonkin [later moving to Voies ferrées de Loc-Ninh:

- Distilleries de l’Indochine (1934), Sucreries et raffineries de l’Indochine (SRIC), Société de chalandage et remorquage de l’Indochine;

- Messageries fluviales de Cochinchine (ca 1925), Comptoirs généraux de l’Indochine (Oct. 1926), Union financière franco-indochinoise (1927), Compagnie saïgonnaise de navigation et de transport (1928), Transports et messageries de l’Indochine, Union électrique d’Indochine, Manufactures indochinoises de cigarettes (1929);

- Plantations de Kantroï (1927), Plantations de Mimot [Memot] (later Plantations réunies de Mimot)(ca 1934), Société urbaine foncière indochinoise.

- Collaboration with Les Marquises, société franco-tchécoslovaque des îles de l’Océanie (1926).

- Declining a proposal from the ailing company Minière du Laos, joins in Indochine films et cinémas, Compagnie franco-indochinoise de radiophonie [Radio Saigon] (1929), and Nouvelle compagnie des Eaux de Hanoï (1930).

- Enters the board of Banque de l’Indochine in 1931, as one of six reprensatatives of the French State.

Publications

- “Hâtien, Phu-quoc et leurs habitants”, Revue indochinoise (RI), 1st sem. 1910.

- Comité de l’Asie française : Conférence sur le Cambodge pittoresque, Paris, 24 June 1910.

- “Le Cambodge et ses ressources”, RI, 2nd sem. 1910.

- Conférences publiques à l’Ecole coloniale (1912−1913) : “La question de l’alcool au Tonkin et dans le Nord-Annam” | “Notre action en Indochine.”

[1] see Pierre Lamant, L’affaire Yuhanthor, autopsie d’un scandale colonial, Paris, Société française d’histoire d’Outré-Mer, l’Harmattan, 1989, 243 p.