Tendances de l'Art Khmer | Trends in Khmer Art

by Jean Boisselier

'Commentaries on 24 Masterpieces at the National Museum of Phnom Penh'.

- Formats

- e-book, on-demand books

- Publisher

- Musée Guimet| Presses Universitaires de France, Vol. LXII, Paris

- Edition

- Digital edition by FeniXX with the support of CNL

- Published

- 1956

- Author

- Jean Boisselier

- Pages

- 157

- Language

- French

Written in 1952, when the National Museum of Cambodia was still known as the Musée Albert-Sarrault — of which the author was then Chief-Curator, this luminous study of 24 Khmer sculpture masterpieces follows the principles and datation system established by art historian Philippe Stern, the author’s mentor.

After briefly depicting the major figures of the Hinduist pantheon in their Khmer representations, the study defines the major trends of Khmer Buddhist art: “Au milieu du panthéon mahâyâniste, ce sont les images

de Lokeçvara, le Bodhisattva de Compassion, et de la Prajñâpâramitâ ou Târâ, la « Perfection de Sagesse » qui sont, de loin, les plus nombreuses. Les unes et les autres sont vêtues comme les divinités hindouistes mais elles portent, en avant de leur chignon, la figurine d’un Buddha assis en méditation. Lokeçvara est, de préférence, représenté avec quatre bras, tenant le flacon, le livre, le rosaire et le bouton de lotus ; mais il peut avoir aussi huit bras ; son corps, sa chevelure même, sont alors recouverts d’une multitude de petites images de Buddha et de divinités que le Bodhisattva est censé irradier pour le salut des êtres. Târâ né possède, tout au moins dans l’art lapidaire, que deux bras, tenant le livre et le bouton de lotus. Les divinités tantriques, à bras et têtes multiples, n’apparaissent pas dans la statuaire proprement dite mais les bronzes et certaines stèles en montrent quelques rares exemples.” [“At the center of the pantheon, the images of Lokesvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, and of Prajñâpâramitâ or Târâ, the “Perfection of Wisdom”, are, by far, the most numerous. Both are dressed like Hindu deities but they wear, in front of their bun, a small figurine of Buddha seated in meditation. Lokesvara is preferably represented with four arms, holding the flask, the book, the rosary and the lotus bud; but he can also have eight arms; his body, his hair even, are then covered with a multitude of small images of Buddha and deities that the Bodhisattva is supposed to radiate for the salvation of beings. Tara has, at least in lapidary art, only two arms, holding the book and the lotus bud. Tantric deities, with multiple arms and heads, do not appear in the actual statuary, but the bronzes and certain stelae show a few rare examples.”]

As for the Khmer statuary style itself, the author notes that “dès 1875, le comte de Croizier écrivait : ‘La statuaire chez les Khmers a été poussée à un haut degré de perfection. Les types reproduits sont des types indigènes : l’expression des figures est souriante et douce, le caractère en est hiératique. Même quand les personnages

sont en mouvement, les formes musculaires né sont pas accusées…Leurs oeuvres ont une originalité incontestable et il est impossible de confondre les statues de l’Inde avec celles qu’on retrouve dans les temples anciens du Cambodge.’ ” [“As early as 1875, Comte de Croizier wrote: ‘Statuary among the Khmers has been brought to a high degree of perfection. The types reproduced are native, the facial expressions smiling and gentle, the character hieratic. Even when the figures are in motion, the muscular forms are not marked… Their works have an undeniable originality and it is impossible to confuse the statues of India with those found in ancient temples of Cambodia.‘”]

ADB Input:

Compare with Philip S. Rawson’s The art of Southeast Asia; Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Java, Bali (Praeger, New York, 1967, p 18): “Most interesting of all, there apparently existed a fairly advanced native artistic tradition in Cambodia and Cochin China [previous to Indian influences, EN] , probably in perishable materials. For when the earliest versions in stone of Indian prototypes were made there, they were far from being mere copies, or even transcriptions. The sculptures of Indian icons produced in Cambodia during the sixth to the eighth centuries ad are masterpieces, monumental, subtle, highly sophisticated, mature in style and unrivalled for sheer beauty anywhere in India. It is obvious that their style is not purely Indian ; there are elements in it which were never created by Indian sculptors in India, and which must only be called local. It is not possible to say whence this style sprang. It must have developed in the region. Attempts to identify it exactly with a specific local Indian style have failed, though certain characteristics suggest links with western rather than eastern India. It cannot have been imported, fully fledged, and there may yet be further discoveries about its evolution to be made.”

The masterpieces here considered and commented are:

1) VISHNU (B‑30, 18) Schiste (height : 2 m. 70), Phnom Dà (Takeo), first half of 6th century

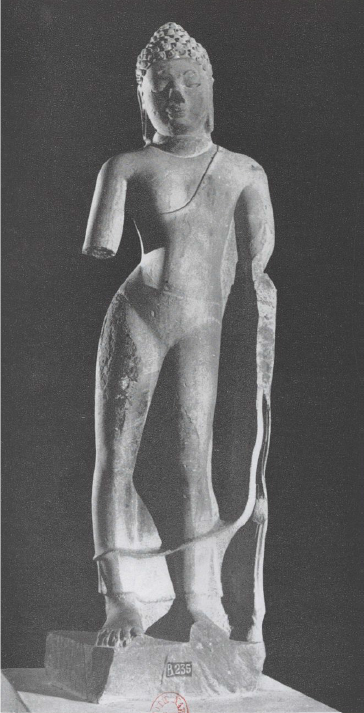

2) STANDING BUDDHA (B‑10, 14) Sandstone (h: 1 m. 25), Wat Romlok (Prei Krabas, Takéo), 6 – 7th centuries

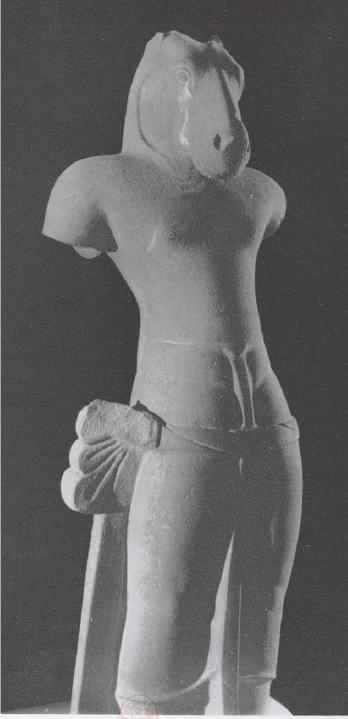

3) KALKYAVATARA (avatar of Vishnu) (V‑31, 2) Sandstone (h: 1 m. 35), found near Kuk Trap village (Kandal), 6 – 7th centuries

4) VISHNU (B‑30, 15) Sandstone (h: 1 m. 85), found at Tûol Dai Buon (Pearang, Prei Veng),7th century

5) FEMALE DEITY (B‑71, 1) Sandstone (h: 1 m. 27), Koh Krieng (Kompong Cham), 7th century

Tags: Khmer art, sculpture, museums, National Museum of Cambodia, art history, statuary, stone cutting, bronze

About the Author

Jean Boisselier

Jean Boisselier (26 Aug 1912, Paris — 26 Feb. 1996, Paris), son of the French military visual artist Henri Boisselier, was a leading specialist in Khmer plastic arts. Curator of Phnom Penh National Museum, he was a member of EFEO (École française d’Extrême-Orient) until 1955, and worked in Angkor as an archaeologist and conservator from 1949 to 1955.

Like so many French writers and archaeologists in the making, he got under the spell of Angkor after seeing a picture of the Khmer temple published by L’Illustration on the occasion of Marseilles Exposition Coloniale in 1922, when he was 10. After completing studies at École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, he became a drawing teacher with the aim of joining the Ecole des Arts Cambodgiens (School of Cambodian Arts) founded by George Groslier in Phnom Penh.

A prisoner of war for five years during Second World War, he joined Ecole du Louvre in 1945 and completed his thesis on Khmer statuary under the supervision of Prof. Philippe Stern, while also teaching drawing and history of Khmer art at Guimet Museum and gave lectures of drawing and history of Khmer art.

After briefly working with Henri Marchal in Angkor in 1949, working on the restoration of Angkor Thom North Gate and Banteay Kdei temple, he was appointed curator of the Museum of Phnom Penh in 1950 after Solange Bernard-Thierry, making sure the Museum as well as the Buddhist Institute’s management was smoothly transfered to Cambodian authorities after the independence, and establishing the first comprehensive catalog of the museum, with more than 6,000 artworks identified and labeled. From 1955, he turned his attention to Thailand, studying the ancient city site of U Thong and the remains of Dvaravati period. Leaving EFEO for Centre national de la recherché scientifique (CNRS), he took part in several archeological missions in Thailand and Sri Lanka. Leading from 1970 to 1980 the research training programme “Archaeology and Civilisations of the South and Southeast Asia” at University Paris III, he was also granted the title of Doctor Honoris Causa by Bangkok Silpakorn University in 1983.

With a deep personal vinculation to Southeast Asian culture and arts, Jean Boisselier liked to practice Buddhist meditation and kept friendly bounds with the Cambodian community in Paris. According to Madeleine Giteau’s obituary in Arts Asiatiques (t. 51, 1996. pp. 138 – 139), “his Cambodian friends brought him solace during particularly painful moments, when his wife passed away in 1987, and after the death of their son Louis in 1991. He entrusted with his last wishes his closest friends in France, HRH Prince and HRH Princess Sisowath Essaro.” [Prince Sisowath Essaro (2 May 1920, Phnom Penh — 12 Aug 2004, Melun, France) had served many years as Cambodian ambassador and representative to the UN.]

Publications

- La statuaire khmère et son évolution. Saigon, EFEO (PEFEO 37), 1955

- Tendances de l’Art khmer. Commentaires sur 24 chefs‑d’œuvre du musée de Phnom Penh Paris, PUF (Publ. du musée Guimet 42), 1956

- “Travaux de M. George Cœdès. Essai de Bibliographie” (with A. Zigmund-Cerbu), Artibus Asiae, Vol. 24, No. 3/4, 1961, pp. 155 – 186.

- La statuaire du Champa. Recherches sur les cultes et l’iconographie, Paris, EFEO (PEFEO 54) 1963

- Asie du Sud-Est : I. Le Cambodge, Paris, Picard (Manuel d’archéologie d’Extrême-Orient, 1) 1966

- Notes sur l’art du bronze dans l’ancien Cambodge, Artibus Asiae 29/4. 1967

- La sculpture en Thaïlande, Fribourg, Office du Livre (Bibliothèque des Arts), 1974

- La peinture en Thaïlande (with Jean-Michel Beurdeley), Fribourg, Office du livre (Bibliothèque des Arts), 1976, deutsche Version: Malerei in Thailand. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3 – 17-002521‑X

- Il Sud-Est asiatico, Turin, Storia Universale dell’ Arte, 1986

- Studies on the Art of Ancient Cambodia, (tr. Natasha Eilenberg and Robert L. Brown), Reyum Publishing, Phnom Penh, 1991

- La sagesse du Bouddha, Découvertes Gallimard n 194, Gallimard, Paris 1993, ISBN 9782070437504 (new editions in 2010, 2019) | UK edition: The Wisdom of the Buddha, New Horizons series, Thames & Hudson, London 1994 | US edition: The Wisdom of the Buddha, Abrams Discoveries series. Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1994

- Bouddha, Gallimard, Paris, 2013 (preface by Trinh Xuan Thuan)