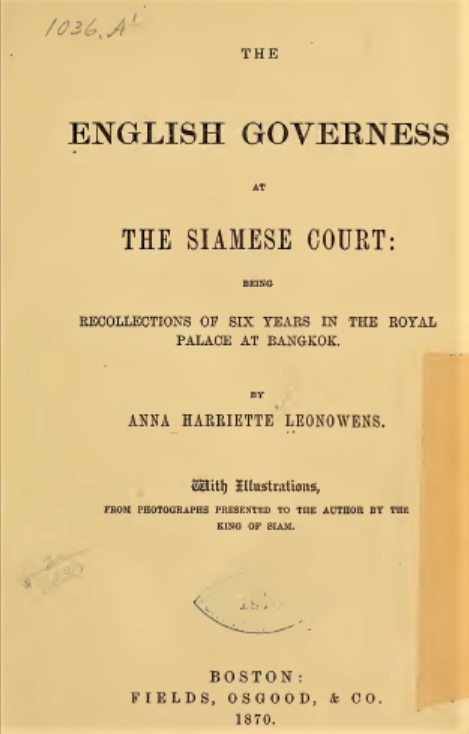

The English Governess at the Siamese Court

by Anna Leonowens

The written account that decades later inspired a best-selling book and a Hollywood musical is nevertheless a valuable document for historians.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Fields, Osgood and Co., Boston, USA

- Edition

- 1) E-edition (pdf) via Blackmask, 2002 | 2) Digital Resources, Library of Congress, USA

- Published

- 1870

- Author

- Anna Leonowens

- Pages

- 321

- Language

- English

When Anna Leonowens’ book was published in 1870, public attention swiftly focused on scandalous details. Siamese King Mongkut and his 39 wives and concubines, his some 87 children, triggered some salacious interest that was later lamented by Thai scholars and leaders for its slanderous character. The “depravity” of Far-East despots, compared to righteous, hard-working and even puritanical Western establishment…The fact that the author had published an excerpt entitled “The Favorite of the Harem” in the American press did not help.

However, when carefully reading again this accoount nowadays, one can only be impressed by how well-informed on Siamese mores the author was, and how carefully she studied details of the life at the Siamese Royal Court and around the country. Some examples:

- The governess paid close attention to the musical performances at Court events and religious functions. In particular, she writes:

The Siamese, naturally imaginative and gay, cultivate music with great zest. Every village has its orchestra, every prince and noble his band of musicians, and in every part of Bangkok the sound of strange instruments is heard continually. Their music is not in parts like ours, but there is always harmony with good expression, and an agreeable variety of movement and volume is derived from the diversity of instruments and the taste of the players. The principal instrument, the khong-vong, is composed of a series of hemispherical metallic bells or cups inverted and suspended by cords to a wooden frame. The performer strikes the bells with two little hammers covered with soft leather, producing an agreeable harmony. The hautboy player (who is usually a professional juggler and snake-charmer also) commonly leads the band. Kneeling and swaying his body forward and backward, and from side to side, he keeps time to the movement of the music. His instrument has six holes, but no keys, and may be either rough or smoothly finished. The ranat, or harmonicon, is a wooden instrument, with keys made of wood from the bashoo-nut tree. These, varying in size from six inches by one to fifteen by two, are connected by pieces of twine, and so fastened to a hollow case of wood about three feet in length and a foot high. The music is “conjured” by the aid of two small hammers corked with leather, like those of the khongvong. The notes are clear and fine, and the instrument admits of much delicacy of touch. Beside these the Siamese have the guitar, the violin, the flute, the cymbals, the trumpet, and the conch-shell. There is the luptima also, another very curious instrument, formed of a dozen long perforated reeds joined with bands and cemented at the joints with wax. The orifice at one end is applied to the lips, and a very moderate degree of skill produces notes so strong and sweet as to remind one of the swell of a church organ. The Laos people have organs and tambourines of different forms; their guitar is almost as agreeable as that of Europe; and of their flutes of several kinds, one is played with the nostril instead of the lips. Another instrument, resembling the banjo of the American negroes, is made from a large long-necked gourd, cut in halves while green, cleaned, dried in the sun, covered with parchment, and strung with from four to six strings. Its notes are pleasing. The takhe, a long guitar with metallic strings, is laid on the floor, and high-born ladies, with fingers armed with shields or nails of gold, draw from it the softest and sweetest sounds. In their funeral ceremonies the chanting of the priests is usually accompanied by the lugubrious wailing music of a sort of clarinet. The songs of Siam are either heroic or amatory; the former celebrating the martial exploits, the latter the more tender adventures, of heroes. (pp169-171)

- As a secretary helping King Mongkut with his English correspondence, Anna Leonowens became accutely aware of the growing rivalry between England and France, and the Kingdom of Siam and France, regarding the control of the Cambodian and Laotian provinces. In particular, she notes that

in 1865, his Majesty and the French Consul at Bangkok had a grave misunderstanding about a proposed modification of a treaty relating to Cambodia. The consul demanded the removal of the prime minister from the commission appointed to arrange the terms of this treaty. The king replied that it was beyond his power to remove the Kralahomle. Afterward, the consul, always irritable and insolent, having nursed his wrath to keep it warm, waylaid the king as he was returning from a temple, and threatened him with war, and what not, if he did not accede to his demands. Whereupon, the poor king, effectually intimidated, took refuge in his palace behind barred gates; and forthwith sent messengers to his astrologers, magicians, and soothsayers, to inquire what the situation prognosticated.

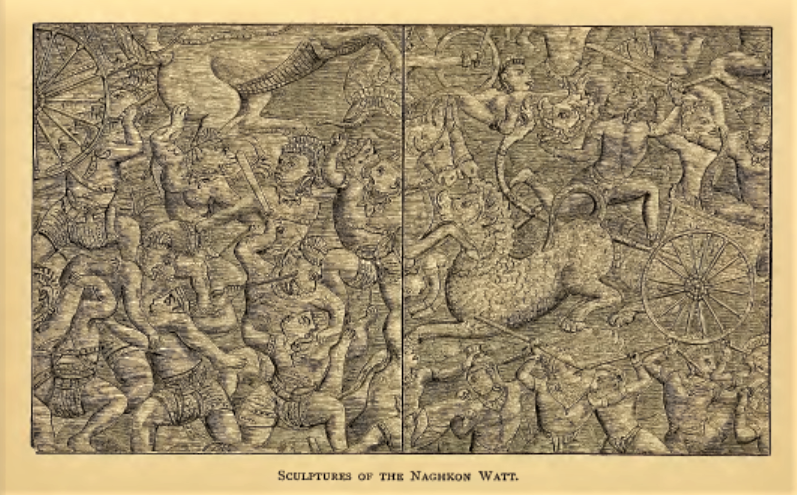

- The author’s relation of her travel to Nagkhon-Wat (Nakhon-Wat, Siamese for Angkor Wat), at the end of the book, seems to have been added in haste, after noticing the growig interest for the illustrious Khmer ruins worldwide. Yet, she had read Henri Mouhot’s accounts, and was in contact with Dr. Adolf Bastian, a somewhat pedantic but keen observer of the Ancient Khmer civilization’s remains. John Thomson, whose photographs were used to illustrate this part, suggested that the author’s had just pilfered Mouhot’s account, noting in his Straits of Malacca (p 130):

There is a slight difference between the two passages. In the one [Mouhot’s] the Wat is simply pronounced the work of some great master; while in the other it resembles an animated, petrified dream, whatever that may be. But other ideas, on the pages quoted, will be found expressed in nearly identical words, furnishing an example of one of those strange coincidences which so startle us occasionally in our experience of life. We regret, however, to discover this authoress, when she describes the Cambodian ruins, falling into a number of grave errors which might, some of them, have been avoided had she studied my photographs more carefully when she did me the honour of selecting them to illustrate her work.

Download the book (pdf format).

email hidden; JavaScript is required

One of the “illustrations from photographs presented to the author by the King of Siam”, to quote the author. It has been proven that these photographs were in fact by John Thomson, and that the author used them without his permission.

Tags: women travelers, women, Siam, musical instruments, explorers, photography, Thai Royal Court, modern history, Angkor Wat, 1870s

About the Author

Anna Leonowens

Anna Harriette Leonowens (born Ann Hariett Emma Edwards: 5 Nov. 1831, Ahmednagar, India (1) – 19 Jan. 1915, Montréal, Canada) was an Anglo-Indian or Indian-born British travel writer, educator, and social activist. She attained worldwide fame when she published her account of her years (1862−1867) as a governess of the wives and children of King of Siam Mongkut, and as his language secretary, The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870).

An avid traveler — she lived in or visited India, Australia, Syria, Egypt, Singapore, Penang (Malaysia), Siam (modern Thailand), England,the USA, Russia, Germany, Canada –, she lectured Indology and Sanskrit at McGill University up to the age of 78. Twice married, a widow at 28 — she took her author’s name from her second husband’s, Thomas Leon Owens) and a mother of four (two children died in infancy), her strong character and her committment as a suffragist triggered hostile reactions from conservative male critics. Accusations of plagiarism and blatant fabrications piled up on her, especially after her life gained posthumous fame with Margaret Landon’s best-selling novel Anna and the King of Siam (1944), and with the highly popular 1951 musical by Rodgers and Hammerstein, The King and I. As critic Maurizio Peleggi wrote, any attempt of a serious biographical profile should be “a demystification [both of] Anna’s deceits and self-delusions, and of American credulity and die-hard preconceptions”, yet not only that…

Co-founder of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in her later years, Anna Leonowens is the first known Western female visitor of Angkor in modern times. Her account on her travel to Naghkon-Wat (Siamese name for Angkor) — Chapter 29 in The English Governess…– , which took place probably in 1866 or 1867 — has been criticized by Scottish photographer John Thomson, even if the author wrote in her foreword: “Those of my readers who may find themselves interested in the wonderful ruins recently discovered in Cambodia are indebted to the earlier travellers, Mr. Henri Mouhot, Dr. A. [Adolf] Bastian, and the able English photographer, James (sic) Thomson, F. R. G. S. L., almost as much as to myself.”

(1) Her “official” obituary (“Mrs Leonowens”, by John McNaughton, Gazette Printing Company, Montréal: 1916, 36 p.) states that her maiden name was “Anna Harriette Crawford, born at Carnarvon in Wales on November 5th, 1834, the daughter of an English gentleman, who died young, and a Welsh mother. The mother, on whom devolved the entire charge of forming her character, was quite uncommonly fitted to undertake that sacred responsibility. She was evidently what her little girl afterwards came in eminent measure to be, a women of force and stout heart.”

These two portraits show the large cross Anna Leonowens used to wear, symbol of her missionary mission around Asia. However, historians have described her as a “Protestant fundamentalist”…