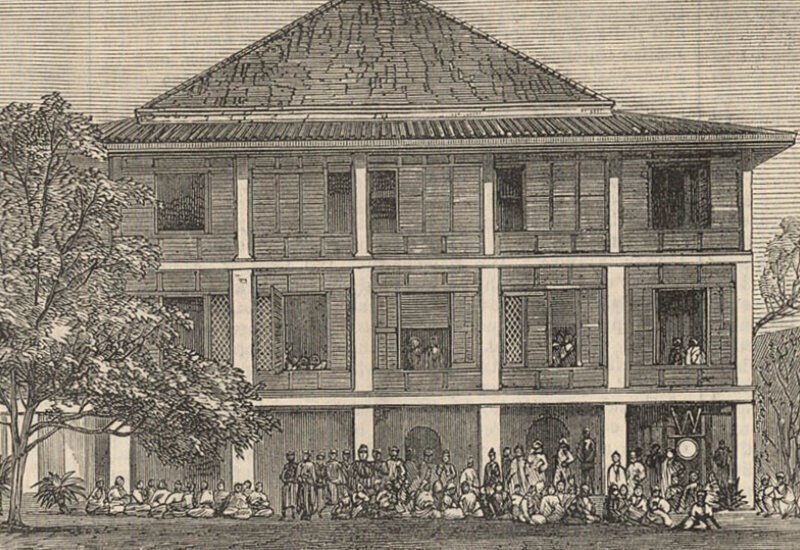

Notes on the Antiquities and Natural History of Cambodia

by James Campbell

These informative notes stand among the earliest descriptions of Angkor and pre-colonial Cambodia by Western travelers.

- Publication

- Journal of The Royal Society of Geography, Vol. XXX, Art. XVII., pp 182-198 | Paper read on June 27, 1859

- Published

- 1859

- Author

- James Campbell

- Pages

- 17

- Language

- English

pdf 1.4 MB

Published at the same time and location that D.O. King’s account, these informative Notes stand among the earliest descriptions of Angkor and pre-colonial Cambodia by Western travelers.

This a collection of various research works, direct experiences and grapevine stories about the Srok Khmer, the Land of the Khmer which then remained mostly out of reach for Western people.

Sources

We can find several mentions or quotations of Western missionaries, traders, diplomats or scientists who were then living in Siam, or had visited the Kingdom:

- ‘The late E.F.J. Forrest’ must be Edward Forrest, who was attached to the first British consulate in Bangkok. According to Eliza Hillier, the wife of Charles Bartlett Hillier, the first Britisht representative between April and November 1856, her husband’s collaborators were “Charles Bell and Edward Forrest— both of whom had been posted to Bangkok by Sir John Bowring after the signing of the Treaty as student-interpreters, primarily to learn the language.” It seems that Forrest was with David Olyphant King during the Cambodian journey, “in the middle of the dry season” [1858] and that he died shortly afterwards.

- Dr. Samuel Reynolds House: this American physician and missionary had a particular interest in Cambodia, since he had befriended in Bangkok one King Ang Duong អង្គឌួង’s eleven sons. According to Dr. House’s biographer (1), “during the cholera epidemic Dr. House was called to see the servant of a Cambodian prince living in Bangkok (2), and the visit resulted in an enduring friendship. The prince, the son of the king of Cambodia, was living in a grand palace provided by the king of Siam; and Dr. House was led to suspect that he was held as hostage for the good behaviour of his father, over whom Siam claimed suzerainty. The prince urged the doctor to go to Cambodia, assuring him that he would be welcomed with open arms by the king (…) The information gained from the prince prompted Dr. House and Mr. Mattoon to plan a trip into that country. They entered upon the study of the language for that purpose, but the death of the old king of Siam arrested these plans. However, the interest awakened in Dr. House led eventually to his notable trip to Korat [Khorat, modern Nakhon Ratchasima, had been part of the Khmer Empire].” In December, 1853, Dr. House did travel to Korat, and “the return trip was laid out through the western part of ancient Cambodia, through the Chong To’ko pass, thence to the headwaters of the Bang Pakong River, and home by way of Kabin and Patchin.”

- When describing the Tonle Sap “Great Lake”, the author mentions the notations of Dr. John Crawfurd (13 August 1783-11 May 1868), a Scottish physician, colonial administrator and diplomat, the last British Resident of Singapore, who had had led the Cruwford Mission through Siam and Cochinchina in 1821 – 1822. Crawfurd published his Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China (London, 1830, 2 vol).

John Crawfurd

- Sir John Bowring, in addition to negotiating the eponymous Treaty with Siam in 1855, and to author some fifty books on subjects as various as Russian poetry, Central European folktales or religious hymns, did write a sum on The Kingdom and People of Siam (with a Narrative of the Mission to that Country in 1855, London, 1857, 2 vol), for which he might have used some of Forrest’s findings but mostly referred to Pallegoix for his remarks related to Cambodia. He also quotes extensively an interesting travelogue, “Three Months in Cambodia, By a Madras Officer, Mission Press, Singapore, 1854.”

- Pallegoix, of course, is quoted, by the details given in the description of Angkor proper go far beyond the quite perfunctory description by the eminent French apostolic vicar of Siam.

From the Notes on the Anquities…

- Tonle Sap and flow reversing: “Besides the river and canal communications above referred to, there is another drainage system in Cambodia worthy of special reference, viz., a great inland lake termed Talae Sap by the inhabitants, but Bien-ho by the Cochin Chinese. It discharges its water into the Mekom, and seems to be the most important and anomalous of the Cambodian aftluents which flow into that mighty stream. This lake does not appear in any of the atlases at my command, and though its position is tolerably well defined in the works of Cruwford, Pallegoix, and Bowring, none of whom I believe saw the lake. Mr. Forrest visited it at the middle of the dry season, and as they do not give any description of it, I append the following: The lake Talae Sap is the result of a depressed basin, situated in a very flat country ; and hence, from its location in a region of periodical rains, is subject to great alternations in its depth. Occasionally in the dry season it is so shallow that boats require to be poled along instead of pulled ; but in the wet season it attains a depth of at least 45 feet, and measures about 100 miles long by 40 at its greatest breadth. It seems remarkably odd that when at its height there is comparatively little surface current, whilst when the waters have somewbat fallen there is a considerable flow. There does not appear to be any increase of water at the embouchures of the Mekom, or of the adjacent sea and gulf, as a result of the south-west monsoon, similar to what I have noticed in the Gulf of Guinea during the line westerly monsoon ; and as the disemboguing outlets of the Cambodian river system are numerous and unobstructed, the anomaly of such a periodical collection of pent-up water seems truly remarkable.”

- Angkor and Superstitions: “Nakon Wat stands like a mighty sphinx frowning contemptuously on the infantine and barbaric state of the arts and science of the people who are now the denizens of the forests and plains in its vicinity, and presents, with its towers and halls so pregnant with mystery and evidences of the past, a wondrous enigma which challenges the wisdom of the world to fathom. A superstition exists in Siam and Cambodia, that should any prince or noble be audacious enough to penetrate into the domains of these ruins they will most assuredly die; and so strong is the belief, that no man of rank has visited them within the memory of the oldest inhabitants of the neighbourhood.”

- Angkor architecture: “This road, which is 30 feet broad, had formerly a balustrade paved with lead, the traces of the fastenings of which to the stone are plainly visible ; but at the time of the invasion of Cambodia by the Siamese in 1835, the ruthless soldiery added the robbery of this to the list of the damage they did to the temple. At intervals abutments with steps, the sides of which were adorned with phya naks [?] and lions, allowed egress from the road to the ground. Halfway between the gateway and temple, on each side of the road, are two small buildings of freestone, which might have been either sacred places or residences for priests; they are now too much blocked up by debris and ruin to admit of inspection. (…) Again, the huge blocks of stone employed in the building, many of them measuring 18 feet in length, and from 3 to 4 feet in breadth, which, notwithstanding that they are put together without cement, leave scarce a trace of their joinings -the excessive delicacy of the chisellings, the artistic contour of the statues, the peculiarity of the design, and the tout-ensemble, so widely different and so incomparably superb to what they have ever seen or heard of elsewhere, cannot fail to inspire them, left, as they are, without legend or tradition to guide them in any way, with the faith that celestial artificers must have been the erectors.”

- A remarkable critic of the Siamese dealings with Angkor: “All the gold, silver, and agate images, once profusely adorning the building, were carried off by the Siamese soldiery in the war of 1835. In alluding to the depredations committed by the Siamese-so essentially votaries of Buddha ‑on a temple of their god renowned for its extraordinary sanctity, it cannot fail to be observed, with respect to the religious idolatry of a barbarous people, how unstable are their faith and tenets. In the case of Nakon Wat all the earliest religious associations of the Siamese were derived thence, whilst the books and faith which they at the present day pretend so much to revere, all emanated from this temple, which, on the occasion of the Siamese army marching against Cambodia, a licentious soldiery, not only unrestrained. but by direction of their leaders, despoiled of its gold and wealth, and broke, in their search for bidden treasures, the finest statues and figures, testimony of which is but too plentifully afforded by the debris and broken limbs scattered throughout the edifice.”

(1) George Haws Feltus, Samuel Reynolds House of Siam, Fleming H. Revell Company, New York, 1924)

(2) The prince is not named. He could have been Prince Ang Sar អង្គសោ, future King of Cambodia as Sisowath ព្រះបាទស៊ីសុវតិ្ថ, future rival to his half-brothers Norodom and Si Votha in King Ang Duong’s succession.

Full title: “Notes on the Antiquities, Natural History, &c. &c., of Cambodia, compiled from manuscripts of the late E.F.J. Forrest, Esq., and from information derived from the Rev. Dr. House, &c. &c.”

Photo: “Like an enigmatic sphynx…” (by @marisjc, 2021)

Tags: 19th century, Siam, Tonle Sap, Nokon, American travelers, American missionaries, British travelers

About the Author

James Campbell

Dr. James Campbell was a British naval surgeon, a naturalist and a geographer based in Bangkok in the 1850s-1870 where, as the ‘physician to the British Legation’, he treated the Queen of Siam and the small community of Western expatriates. According to Anna Leonowens, he attempted to save the life of King Mongkut’s “favorite daughter”, Fa-Ying, stricken by cholera, to no avail, in May 1863.

As a geographer, James Campbell helped Henri Mouhot in setting up his travels — the latter thanked him (along with botanist and explorer Robert Hermann Schomburgk in the English version of his travelogue –, and assisted various expeditions to Angkor (then under Siamese rule).

Dr. Campbell was appointed physician to the Bangkok British Legation (or Consulate) — installed by Charles Bartlett Hillier in 1856 — on Jan. 29, 1857. His medical research led him to publish an article on puberty average age among Thai girls — “On the Age at Which Menstruation Begins in Siam”, communication read to the Obstetrical Society of Edinburgh, 6 Aug. 1862.) and released in Edinburgh Medical Journal, Sept 1862 –, in which he noted that

I have been told that the Siamese now menstruate at an earlier age than fifty years ago; and an old nobleman, who adheres to this view, once called some of his aged dependents to illustrate the point: he failed, however, as most of the aged women gave a year earlier than that which obtained in the cases of their daughters. He likewise gave as a reason that, in his youth, women of fifteen and upwards were wont to bathe nude in the rivers and canals, whereas now, from more speedy development, they never do so at that age.

His numerous scientific interests included meteorology, and in 1860 the Bangkok Calendar published his ‘Meteorogical Tables’, along with those drafted by Rev. Jesse Caswell, a priest working under the patronage of the American Missionary Association. In a letter to Dr. Bradley on 1st January 1859, Campbell had noted that

The temperatures I believe to be the most correct of any recorded for Bangkok: for I take it those hitherto noted were not from self-registering instruments, or if so, that they were not so accurate as those now made. My thermometers were tested at Kew and Greenwich observatories. The same remarks apply to the Hygrometer.” [see Hugh Campbell Highet (1867−1872, who succedeed James Campbell at the Legation], “The Climate of Bangkok”, Journal of Siam Society, 9, 1912]

On a 1861 map of Bangkok, it appears that Dr. Campbell’s house, south of the Fort on the Menam River, was adjacent to the British and French Consulates, and close to the American Mission and to Mgr Pallegoix’s residence. In 1870, he was still listed as the Consulate Surgeon in the Chronicle and Directory for China, Japan and The Philippines (Hong Kong, 1870).