November 1967: Jackie K. Goes To Cambodia

by Angkor Database

As a Netflix movie will soon re-create this moment, we revisit a visit surrounded with political tragedy, romance and desperation, and the looming Vietnam War.

- Publication

- ADB Reference Studies #JK-NS4

- Published

- 2021

- Author

- Angkor Database

- Pages

- 1

- Language

- English

pdf 2.7 MB

With a major Netflix feature movie set to be shot in Angkor — a revised version of the script was approved during 2023 summer – , the visit of Jacqueline Kennedy to Cambodia on 2 – 8 November 1967, recently declassified documents and a fresh approach of the historic context give us new perspectives on a legendary moment.

Was the visit a carefully planned operation aimed at mending fences between Cambodia and the US, as diplomatic ties had been severed in May 1965, or just a way for a traumatized Jacqueline to escape from the stiffling atmosphere of Washington and to realize her childhood dream to see Angkor? Both, we are tempted to say, with the following caveats:

- The Lyndon Johnson administration was highly ambivalent towards Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the Cambodian Head of State at the time. The US military intelligence, in particular, was harshly critical of his “unpredictability”, meaning his reluctance to stay silent regarding increasing US incursions on Cambodian territory and the hawkish approach to the Vietnam War.

- Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defence, was increasingly distressed by the military intervention, culminating with his resignation in August 1967. A close confident of Jacqueline Kennedy, he had encouraged her to consider a semi private visit in Cambodia since 1966, but feared the tensions inside the US administration would negatively impact it.

- Norodom Sihanouk himself was unsure of the America’s ultimate motive. He feared an attempt to oust him from power by the CIA, an apprehension that will later materialize with the Lon Nol coup in March 1970, and which is expressed in his book My War With the CIA, and in his movie Crépuscule (Twilight), released in 1969 but on which he was working at the time of Mrs Kennedy’s visit.

- The rise of the “Cultural Revolution” supporters in China was threatening the frail balance he had managed to find between left and right wings in Cambodia. Later on, the ‘King Father’ would remark that Jacqueline Kennedy’s invitation to Cambodia had been a way “to please the pro-American elements in our country, Lon Nol and such”.

- Until the last moment, both parties kept the visit ambiguously “private-official”, and Prince Sihanouk quite mischeviously expressed astonishment when Jackie, who had planned to come over in March 1967, expressed some frustration when he informed the Americans he wouldn’t be in Cambodia to welcome her: “What is the matter, if the visit is not official?”, he replied. At the end, he made sure the visit did not lack the luster and pomp of an official visit, and according to Son Soubert, son of the then Cambodian prime minister Son Sann, “her journey was the first that re-started relations with the United States” (Harriett Fitch Little, Phnom Penh Post, 20 March 2015).

- In this highly volatile context, Jacqueline Kennedy sought the support of long-term friends (and admirers), firstly David Ormsby-Gore, Lord Harlech, a former British diplomat that was to start a career as TV executive producer with Harlech Television (later HTV) and who was also recently widowed. Two old friends were also part of the trip: Michael V. Forrestal (1927−1989), a diplomatic adviser to JFK who had taken an active part in the ousting of the first president of South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, and who acted as State Department liaison during the visit even if McNamara hated him with a passion; and Charles L. Bartlett (1921−2017). a Georgetown journalist who had dated Jackie before serving as as matchmaker for JFK and her (with his wife, Martha).

- Jackie’s personal interest in Cambodia and its history was genuine. In addition to her long-lasting fascination with India, which she visited on several occasions from 1962 to 1984 — she wore Indian-inspired dresses by Valentino during the trip –, she mentioned to Prince Sihanouk in a letter in February 1967 that she had chosen the “Memoirs of Tcheou-Ta-Kuan” (Zhou Daguan) for a French-English translation school assignment in high-school.

In addition to the documents included in our publication, we are adding several insights below:

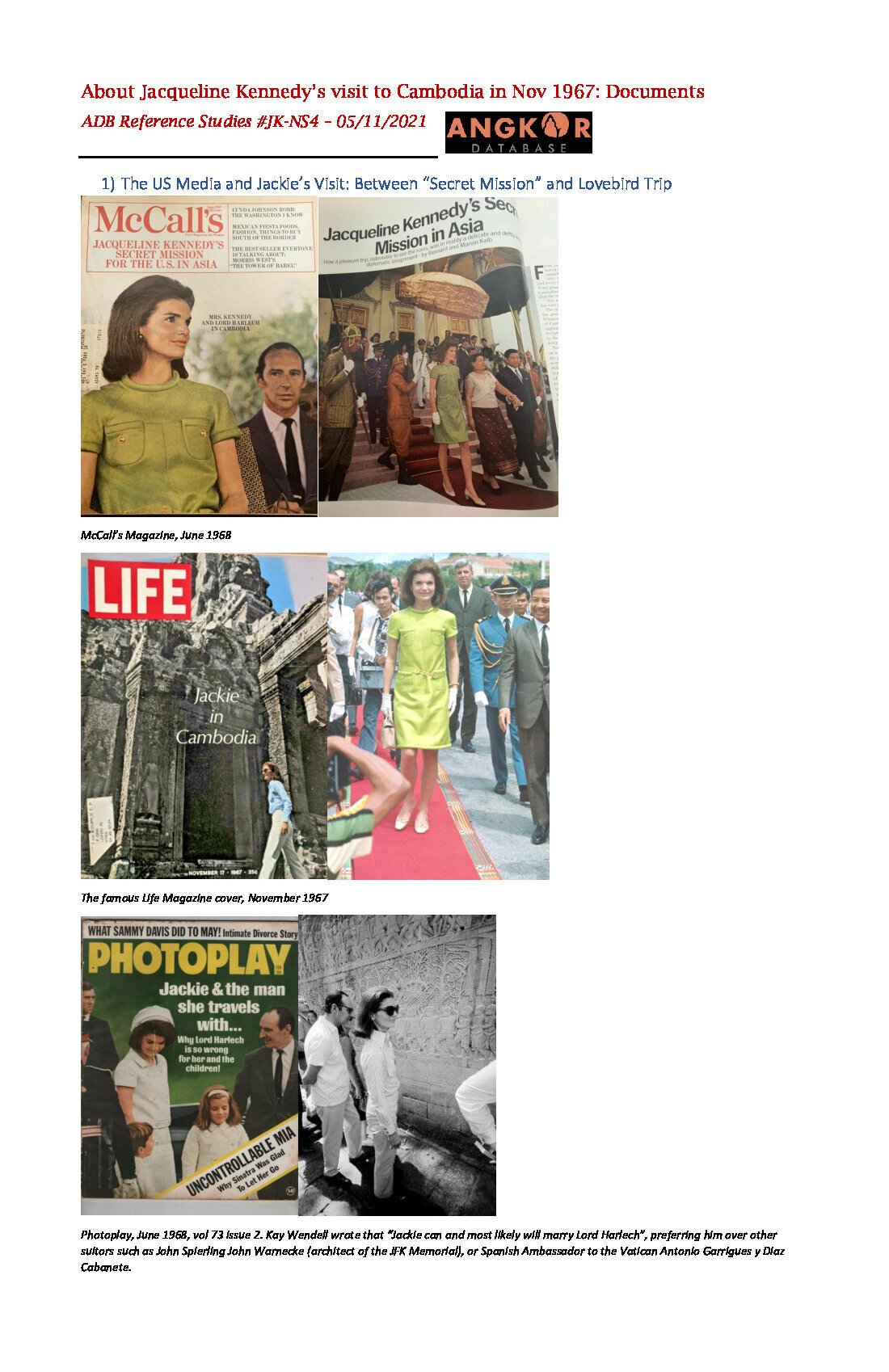

“A Semi Political Mission” with a Romance Smokescreen?

- In A Woman Named Jackie (1989), C. David Heymann remarks: “To help guide her, Jackie had decided to take Lord Harlech, a skilled and experienced British diplomat, while Forrestal was both a trusted friend and an expert in Southeast Asian affairs. Leaving from New York, Jackie stopped over in Rome for three days, then boarded a commercial jetliner whose first-class compartment had been turned into a bedroom for Jackie for the twelve-hour flight [The Alitalia flight was even delayed 25 minutes on Oct.31 to allow Harlech, who was flying from London, to join the party. Jackie and her entourage then flew on Nov. 2 from Bangkok to Phnom Penh on a US Air Force C54, the first American plane to land in Cambodia since 1965.] Prince Sihanouk’s welcome at Phnom Penh airport presented Jackie’s advisers with their first obstacle. Scrutinizing an advance copy of the speech, Lord Harlech came across a comment bound to give offense. What the Prince proposed to say was that had President Kennedy lived, there would now be no war in Vietnam. Uttered as part of a welcoming speech for Mrs. Kennedy, the remark would have the same effect as some of William Manchester’s anti-Johnson statements in Death of a President. Lord Harlech advised Jackie to appeal to Sihanouk to eliminate the passage. The request was made from the airplane by two-way radio. The Prince consented. In return, Jackie agreed to add a line to her arrival address, affirming that “President Kennedy would have loved to visit Cambodia.”

- In his cable to the US Secretary of State on Nov. 8, sent from Bangkok a few hours after the end of the Cambodia visit, Michael Forrestal noted that David Harlech did take part with some political conversations in Phnom Penh with Prince Sihanouk and some of his ministers, but “nothing [the Prince] said adds in any way to what is already available in public form through the Prince’s various press conferences and the related articles which appeared in the Cambodian press during our stay.”

- While the Chinese leaders, in particular Zhou Enlai, never faltered in their support, Prince Sihanouk had some reason to distrust the loyalty of all his American counterparts. In My War With the CIA (1973), written with William Burchett while he was exiled, he noted: “Indeed, I must consider myself more fortunate than some of those who worked for my destruction. On 1st November of 1963, my two arch-enemies, Ngo Diem and Ngo Dihn Nhu, were assassinated with CIA help, and ten days later it was the President of United States himself who fell. Incidentally, I must correct an error which unfortunately was printed in the American press. I did, in fact, order three days of national celebrations when the detestable Saigon dictatorship ended. But, at the time of the assassination of President Kennedy, many of our shops displayed his portrait in their windows as a sign of respect. (…) Later I named a boulevard in Sihanoukville in his memory, and it was his widow, Jacqueline, who inaugurated the boulevard on 2 November 1967.” (p 128)

- Cambodia’s King Father has always dismissed the notion that the visit could have led him to a more conciliatory stance towards USA. Two days before the American emissary Chester Bowles arrived in Phnom Penh on 9 January 1968, paving the way to the restoration of diplomatic ties, Prince Sihanouk exclaimed during a press conference broadcasted by Radio Phnom Penh (quoted by the New York Times, 11 Jan. 1968): “They wanted to give [this] visit significance! They wanted Jackie to be able to re-establish diplomatic relations between Cambodia and the United States without the United States having to fulfill the conditions set by Cambodia! They wanted Jackie to obtain the repatriation of all prisoners, civilian and military, currently imprisoned by the National Liberation Front! They wanted Jackie to obtain I don’t know what!”

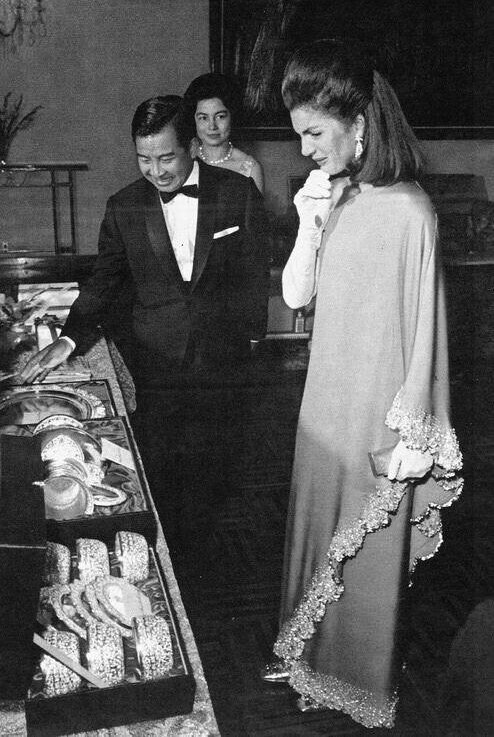

- If the former US First Lady was reportedly “exhausted” at the end of the visit, it was also because the Cambodian side squeezed into the programme last-minute events aimed at showcasing a young country proud of its independence and achievments. Such as the visit to the Sangkum Permanent Exhibition in Phnom Penh. On this photo (from Ingrid Muan’s documented study, “States of Panic: Procedures of the Present in 1950s Cambodia”), Prince Sihanouk shows to Mrs Kennedy — with a bespectacled David Harlech never far behind — the Sangkum way of an independent nation that most of the American leaders still considered as a mere “boundary of the Free World in danger of being lost to the Communists”:

“America’s Queen” & and Her Court Jesters

For Puritan America, Jacqueline Kennedy was “Miss Narcissist, the Temptress of Her Age”. Still haunted by the shadows cast by JFK’s assassination, she was emotionally frail, and caught between a rock and a hard place as the Johnson administration was internally shaken by the Vietnam War.

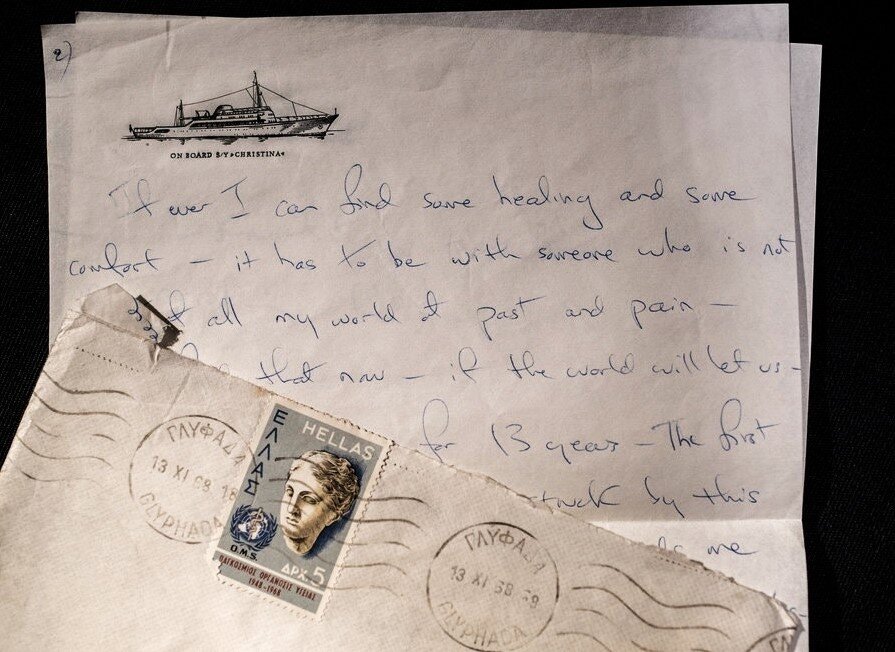

- In Jackie Oh! (1979), Kitty Kelley wrote: “Rumors continued to fly regarding her relationships with Lord Harlech and Roswell Gilpatric, and Jackie continued to be seen with both of them in public. She frequently borrowed other women’s husbands for escorts, and men like Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr., Richard Goodwin, Robert McNamara, and John Kenneth Galbraith were glad to take her to the theater or the ballet. The other men she was seeing at the time — Mike Nichols, Chuck Spalding, Michael Forrestal [who accompanied her to Cambodia], William Walton, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Truman Capote — were all connected in some way with the Kennedy administration. Some were single. Some were gay. All were safe.” (…) As Jackie continued being seen in public with Lord Harlech, going to the ballet, to the theater, to dinner, and flying to Harvard to confer on the Kennedy Library, the speculation increased. Embarrassed by the worldwide press coverage, Lord Harlech issued a statement: “Mrs. Kennedy and I have been close friends for 13 years but there is no truth to the story of a romance between us. I deny it flatly.” Jackie publicly denied the rumors as well as privately reassuring her friends that she would never marry Lord Harlech. (Martha Bartlett recalled her saying, “Cuddling up to him is like cuddling the encyclopedia.”) Her sister, Lee [Radziwill], laughed uproariously when asked about the relationship. “Are you kidding?” she said. “Have you ever seen him?” She thought Harlech looked ridiculously unattractive.”

- Apart from Lord Harlech, many suitable and handsome men have fell under public scrutiny as potential partners for the widowed First Lady. Just a few months after the Cambodian escapade, in March 1968, Jacqueline Kennedy visited the Mayan ruins in Mexico with Roswell Gilpatric, a US Congressman and former Deputy Secretary of Defense under Kennedy. Angus Ash, covering the Mexican trip for Womens Wear Daily, reported that “there was a lot of public smooching and hand-holding between Jackie and Gilpatric. It took place in full view of the press. Jackie was all over the place, at one point jumping into a stream, fully dressed. John Walsh, her Secret Service agent, had to go in after her. Another time she climbed one of the Mayan pyramids and posed like the Queen of England opening Ascot.”

Between Hell and Heavens

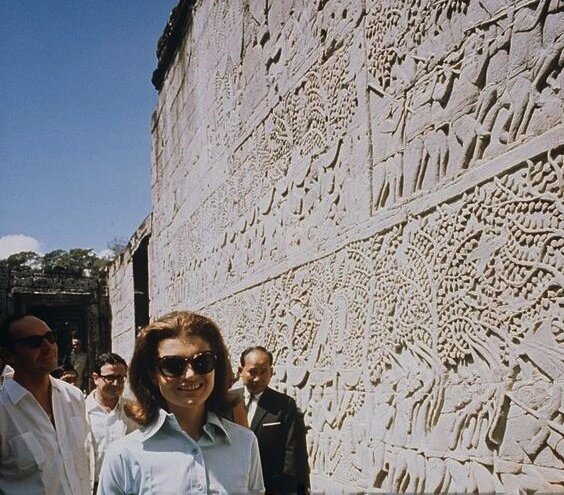

The title for the projected movie, 37 Heavens, alludes to Angkor Wat Southeast Gallery and its bas-reliefs depicting the Hindu-inspired representation of celestial bliss and hellish punishments of the sinners. Bernard-Philippe Groslier was just completing the restoration of this section as the head of the Angkor Conservation, and he spent some time there while guiding Jackie through the Khmer ruins, but if the powerful images so impressed Jacqueline Kennedy, it was also because they echoed her own existential doubts and torments:

- In his memoirs, Robert McNamara noted that Jackie was regularly seeing her Catholic spiritual guide [Father McSorley], questioned her own faith and was prone to sudden bouts of rage about her husband’s tragic end. He recalled that one night, while having a tête-à-tête dinner at his place, Jackie started to weep in anger and even to pound his chest with her fists after they had discussed the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral’s poem “Prayer,” a plea to God to forgive the compulsively unfaithful man she loved (“You say he was cruel? You forget I loved him ever.… To love … is a bitter task”). “Whether her emotions were triggered by the poem or by something I said, I do not know,” wrote McNamara.

- In Nemesis,The True-Story of Aristotle Onassis, Jackie O and the Love Triangle That Brought Down the Kennedys, Paul Evans maintains that Jackie’s main priority since the aftermath of JFK’s assassination was to distance herself from the Kennedys, and that “she did not want her children to grow up in thrall to the Kennedy ethos”. Onassis’ choice was the most radical way to cut ties, especially after Robert ‘Bobby’ Kennedy’s assassination in June 1968. Lord Harlech, who was related to the clan by a cousin’s marriage, who had been JFK’s close friend and who was on the pall-bearers at Bobby Kennedy’s funeral, was thus somehow put at a disadvantage by his proximity with the Kennedys.

- Pressured by the advances of powerful men, including Robert Kennedy and President Johnson himself, appalled by the rising violence within the American society, Jacqueline Kennedy “wanted to escape”, according to the Kennedys’ biographer Barbara Leaming. Sir David Ormsby Gore “of course fell in love with her— she understood him so well,” she said, “but I have no idea if it was consummated or not.”

- All things considered, the trip to Angkor “was the end, rather than the beginning of the relationship,” according to Sarah Bradford in America’s Queen (2000), the book on which the movie Jackie was based. Pamela Colin, Harlech’s second wife, confided to the biographer that “by the time he got back from Angkor Wat, I think David had it up to here…but if Jackie had wanted David, she could have had him.” One year after the Angkor catharsis, Jackie surprised everyone by marrying Greek tycoon Aristotle Onassis, Bobby Kennedy’s bête noire, and in December 1969 Lord Harlech also did marry again, to Pamela, an American editor of Vogue who looked a lot like Jackie. Tragedy, the tragedy that Jackie had been plagued with for years, was never far from him: while his first wife had died in a car accident in 1967, he lost his life in the exact same circumstances in 1985, at 66. Jackie, then Mrs. Onassis, attended his funeral.

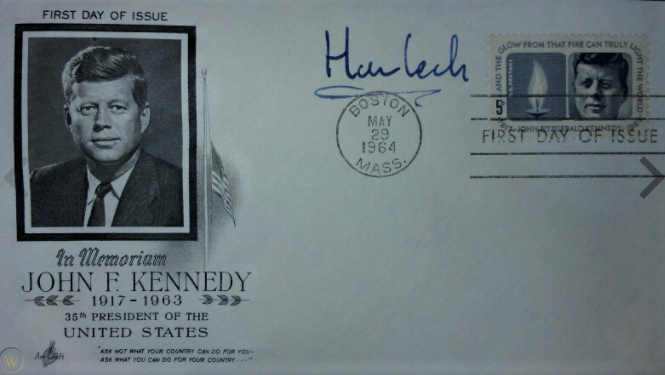

Too close for comfort? Lord Harlech behind JFK at the signing of the proclamation granting Honorary Citizenship of America to Winston Churchill in April 1963 (photo JFK Library); A commemorative stamp issue with Lord Harlech’s autograph (Web)

An Inspiration for Researching Cambodian History

Ambassador Julio Jeldres, who was to become personal secretary and official biographer of HM King Norodom Sihanouk, has kept to these days the Life magazine issue reporting Jackie’s visit to Angkor and her alleged romantic involvement with Lord Harlech at the time. He has just released his study on Sihanouk-Zhou Enlai exceptional friendship, a research inspired by the event fifty-four years earlier. He recalls:

“I was sixteen years old when I first read about Norodom Sihanouk and Cambodia. Jacqueline Kennedy’s visit to Cambodia in November 1967 had been widely reported by the press in my homeland, Chile, where her assassinated husband was greatly admired. Through Jackie Kennedy’s visit to Cambodia, I became interested in Norodom Sihanouk’s fascinating life, totally unaware that, years later, our paths would cross and I would become his private secretary. My Cambodian friends often tell me that it was my destiny. In 1967, I wanted to know more about Cambodia. Since there was no information available, I wrote to the Cambodian mission at the United Nations. I found it unbelievable, but four months later I received a handwritten letter back from Sihanouk himself. That began our friendship, which was first conducted through correspondence.

“After Sihanouk was deposed in March 1970, I discovered that the local New China News Agency branch in Santiago, Chile, carried copies in Spanish of all of Sihanouk’s statements made in the Chinese capital a day earlier. It didn’t seem to make sense that a Communist régime would extend such courtesies to a former monarch. This led me to one aspect of Sihanouk’s political life that I found especially intriguing: his association with Chinese premier Zhou Enlai. This relationship seemed to be a very special one between the head of state of a Buddhist kingdom and the prime minister of a Communist state. As a novice in international affairs, I knew little about how relationships operated between states, yet it still seemed strange to me that a ruler who claimed to be descended from the kings of Angkor had a unique relationship with the political leader of a country ideologically opposed to monarchical government.”

The visit seen by an American soldier

In his essay “How Jacqueline Kennedy Saved My Life” (26 July 1999), Anthony St. John, then a lieutenant in the US Army (and part of a unit operating close to the Cambodian border) recalls:

“My diary says that on 9 November 1967 I was sitting at the edge of a foxhole sloshing with my boots the rain water which had fallen during the night (…) “Lieutenant! Lieutenant!! Lieutenant!!!’’I looked up and there stood an eighteen-year-old grunt from Tennessee screaming at me — his eyes filled with frustration and anger. In his hands he held a copy of Stars and Stripes — the soldier’s daily newspaper. The headline he had thrust in my face explained to me the motive for his excitement: JACKIE KENNEDY VISITS CAMBODIA.“Lieutenant, how could she do that? How could she go on vacation there while we are fighting here? How could she be so inconsiderate?” I tried to calm him down and succeeded somewhat. [Later, in the chopper that had “extracted” them] In the air I pondered the matter over and over and over. I thought back to a little concise statement I once had seen carved on my university dorm’s bathroom door: WE DO TO BE — Camus; WE BE TO DO — Sartre; DO BE DO BE DO — Sinatra! I at once felt I had to do something; I felt I had to choose to be free; and, I felt I could not let this predicament go unchallenged, could not let it escape the scrutiny of those who had sent us to war. I wanted this dilemma to be disentangled.

“I wrote a letter to the President of the United States, Lyndon Baines Johnson, protesting the circumstances. Further, I asked him if I could resign my commission in the middle of a war just as Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara had done then just recently (…) I received a letter from the Under Secretary of State for Asian Affairs, Dixon Donnelly, instructing me to pay heed to the Southeast Treaty Organisation (SEATO), and listen to the suggestions of my superiors. (I would not do otherwise!) A few weeks passed before I was removed from the field (combat zone). A supply sergeant in base camp told me I was a “P.I.,” Political Influence, and would not be sent to the field again for fear that I might “subvert” the thinking of the troops! He told me I would be assigned to those slots reserved for “dummy” lieutenants, and the record of those assignments would guarantee the end of my Army career. Why was I so lucky? At this time, the events leading to the battle of Dak To were fermenting. My former unit was involved in the initial contacts of what would come to be the biggest battle of the “war.” My company lost thirteen and numerous wounded were reported. The unit was effectively deactivated. Individuals sent in my place were killed. What I had originally conceived to be a difficult — but necessary — decision made on my part, turned out also to be a tragedy for others. (…) For many years afterward, I mused on what Jacqueline Kennedy might have answered me if I had come to inform her about that absurd chain of events edifying neither for her nor for me.”

New Insights on a Fateful Visit [August 2023]

The 2023 addition to the large bibiographical corpus on Jacqueline Bouvier-Kennedy-Onassis, J. Randy Taraborrelli’s Jackie: Public, Private, Secret (Saint Martin’s Press, New York, 2023-Kindle Books), sheds a novel light on the Cambodia’s visit [1]. Based on 2022 interviews with Thea Andino, Merope Konialidis’ secretary (Merope was Aristoteles Onassis’ half-sister), we read an account of how a distraught Jackie narrated her Cambodian trip to Merope and Artemis Garoufalidis, Onassis’s eldest sister, during an intimate get-together in December 1967, a few weeks after the visit:

“Mrs. Konialidis told me [Thea Andino] the three of them clustered together at the end of a long, antique wooden table. It was intimate and cozy even considering the length of the table, which I knew seated a dozen. Before them, on a handmade silk tablecloth, was a feast of Greek delicacies including Artemis’s special meatballs with chili along with Italian cheeses and French breads and Merope’s baklava and galaktoboureko [crème caramel] for dessert. It was served by two nervous handmaids and a butler named Panagiotis, who lorded over the whole thing while seeing to their every need, even if that meant just topping off their Greek coffee. They were smoking, all three of them, like chimneys. Typical lunch at Artemis’s.”

“You seem so sad to me,” Artemis said to Jackie. “Are you unhappy? Or am I misunderstanding?” Their conversation was in French, of course. It was a good question. Ordinarily, Jackie would just say all was well. She wasn’t a woman given to confiding in people she barely knew. However, something about these two made her want to unburden herself. She told them about a truly embarrassing encounter she’d recently had with an old friend, the British diplomat David Ormsby-Gore. […] Jackie said she had an idea to visit the twelfth-century temples of Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Even though the United States had severed relations with Cambodia because of the Vietnam War, Robert McNamara was able to pull some strings and get Cambodia’s chief of state, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, to agree to the visit. Jackie then asked Lord Harlech to accompany in case she needed to call upon his diplomatic skills. Once there, she confided to Artemis and Merope, she and David made love. Afterward, Jackie said she regretted it and felt it had been a terrible mistake.

“When she told him she was on the rebound — probably from Jack Warnecke — he was upset. The next day, they began to argue about her obligations to Prince Sihanouk and her insistence that she do only so much publicity, which wasn’t much. David accused her of being “childish and spoiled,” which hurt her feelings. She knew his anger stemmed from her rejection of him, and now, she said, she felt stuck in Cambodia with him. What was she to do? To make things worse, in the middle of this conflict, completely out of the blue, David asked her to marry him. Jackie said she was stunned. She had no feelings for David other than friendship. Two days later, CBS reported she would shortly announce her engagement to him. Even Lady Bird sent word of congratulations, which was humiliating. Jackie assumed David had planted the story in advance, thinking she’d accept his proposal. She found it all deeply disturbing.

“Artemis told Jackie she needed someone in her life with whom she shared a spark, someone like her brother. Changing the subject, Jackie said she had complications in her life far more pressing than who she should date. “I’m known for my lifestyle,” Jackie said, “you can understand that.” Of course, the Onassis women could relate; few had bigger lifestyles than they did. Jackie wasn’t specific about her financial issues, but the Onassis women came to understand that she wasn’t swimming in money. “Artemis told her, ‘A woman like you with such problems, it’s unbelievable,’” recalled Thea Andino. “She said, ‘You must remember that money means nothing,’ and told her she’d hate for her to have even a second’s worry about something so meaningless. She also said, ‘I have a feeling money will be there for you soon.’” [pp 222 – 224; highlights by ADB]

[1] The title comes from a remark made by Jackie to ex-lover and confident John Carl Warnecke in 1989: “Oh, Jack, you know me: I have three lives. Public, private, and secret.” And Taraborrelli the ultimate biographer to add: ‘What’s the point of a biography if it doesn’t reveal secrets?’

Angkor Again, 1973

J. Randy Taraborrelli (op. cit.) has another meaningful anedcote to share, once again related to Angkor:

Back in 1973, Jackie was asked by her friend Karen Lerner to narrate an NBC documentary on Angkor Wat and Venice. Ari didn’t want her to do it, and the two fought furiously about it. “Greek wives don’t work,” he insisted. He wore her down, and she eventually declined the opportunity, but she regretted it. Two years later, she’d begin to date Michael in part because he reminded her of Ari — and now he was acting just like him. In other words, her third act was looking an awful lot like her second. “You have to choose,” he told her. “Me or the job.” This sent up a red flag she couldn’t ignore. “Any time a man asks you to choose, you know what you’re in for if you choose him,” Jackie later told Artemis. “This may explain why he never married. I told him I needed alignment in my life at this time, not opposition.”

On September 22, 1975, Jackie began work as an associate editor at Viking Press on Madison Avenue. And she was successful in that new, unforseen career.

The ‘Femme Fatale’ Lipstick at the Royal-Raffles

During her Phnom Penh stay, Jacqueline Kennedy was hosted at the Chamkarmom Royal Residence, in the suit that had been entirely remodeled for French President Charles de Gaulle during his official three-day visit in September 1966. Prince Sihanouk had oversaw every detail, down to the special-sized bathtub flown from France to accommodate the super-tall Gallic leader.

Mrs Kennedy did enjoy a drink at the Royal Hotel (Raffles), and the cocktail created in her honor, Femme Fatale (champagne, cognac and wild strawberry cream), can still be enjoyed today, while the 33 glasses designed for the visit are still on display. Until the late 2010s, a tradition was kept at the luxury resort: every once in a while, one female staff member would leave a refreshed lipstick smear on the rim of the glass supposedly used by the illustrious and glamorous visitor. On the photos recently shared with us by the Royal-Raffles management, the lipstick is still noticeable, yet slowly fading away…

The famous glass in 2021 (photo Raffles) and, below, as it was exhibited in 2015 (photo Elie Meixier). And both the drink (with lipstick) and the muse in Christian Develter’s ‘Jackie’, a limited-edition lithograph (photo courtesy of the artist):

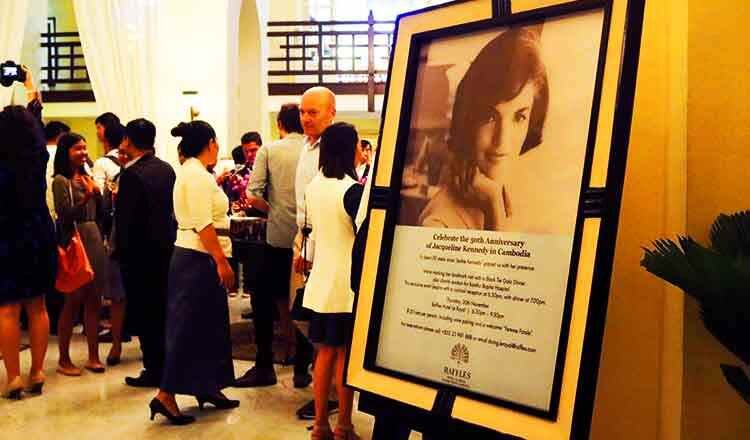

50th Anniversary of Mrs Kennedy visit, Royal-Raffles Hotel (photo Phnom Penh Post):

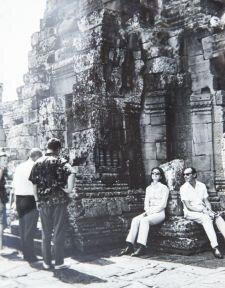

Main photo: Jacqueline Kennedy with Angkor Conservator Bernard-Philippe Groslier (Lord Harlech next to them) at Angkor Wat, Nov. 1967

Tags: Vietnam War, USA-Cambodia, Modern Cambodia

About the Author

Angkor Database

Angkor Database — មូលដ្ឋានទិន្នន័យអង្គរ — 吴哥数据库

All you want to know about Angkor and the Ancient Khmer civilization, how it keeps attracting worldwide attention and permeates modern Cambodia.

Indexed and reviewed books, online documentation, photo and film collections, enriched authors’ biographies, searchable publications.

ជាអ្វីគ្រប់យ៉ាងដែលអ្នកទាំងអស់គ្នាចង់ដឹងអំពីអង្គរ, អរិយធម៌ខ្មែរពីបុរាណ, និងមូលហេតុអ្វីដែលធ្វើឲ្យមានការទាក់ទាញចាប់អារម្មណ៍ពីទូទាំងពិភពលោកបូករួមទាំងប្រទេសកម្ពុជានាសម័យឥឡូវនេះផងដែរ។

Our resources include a physical library library at Templation Angkor Resort, Siem Reap, Cambodia.

email hidden; JavaScript is required