Quinze jours au Cambodge [A Fortnight in Cambodia]

Subheader: "Moeurs, Coutumes, Superstitions, Légendes: Excursion dans les provinces de Roléia-Paier et Compong-Leng".

- Publication

- Société Languedocienne de Géographie (3 installments, June, September and October 1884)

- Published

- 1884

- Pages

- 126

- Language

- French

pdf 5.8 MB

This rare account on rural Cambodia and Phnom Penh in 1879 and 1882, published in the bulletin of Société Languedocienne de Géographie in 1884, was signed by “MM. L.C. Roux et J.M. Vidal, Officiers du Corps de Santé de la Marine (Souvenirs intimes).” So far, we’ve been unable to find out biographical information on them, especially J.M. Vidal who penned the essay, except that they were based in Tonkin and apparently came to Cambodia at the invitation of Dr. Hahn, then personal physician of King Norodom I, respectfully called លោកគ្រូពេទ្យ (Lok Kru Pet, ‘Mister Doctor’) by the Cambodian people.

In addition to giving the earliest description of the “Maison de Fer” (Iron House) at Phnom Penh Royal, this elegant and enigmatic pavilion which remains the only structure surviving from the 1866 – 1880 version of the Palace, the authors share some important observations about the court life and the mores of Cambodia:

Origin of the Cambodian people

“Les Cambodgiens paraissent remonter très haut dans l’histoire. 1°Le roi dit à qui l’interroge là-dessus, qu’il est de tradition dans la famille royale qu’elle descend de Bénarès, dans l’Inde. 2° Il existe dans l’Inde Brahmanique une légende qui parle d’un Rajah qui leva une armée de Scythes et de Kampoutchées or, ce nom Kampoutchées existe sur un cachet du roi actuel. 3° On sait que les Chinois entretenaient des relations avec les rois du Cambodge. Or, les annales chinoises parlent d’une ambassade qui raconte qu’en l’an 20 avant le Christ les eaux des lacs baignaient Angkor; donc Angkor existait alors. 4° Les annales de Ceylan disent qu’avant l’an 105 après le Christ, les Kampoutchées ou Cambodjias firent une invasion dans l’Inde et battirent les Indiens.”

[“The Cambodians seem to go back very far in history. 1° The king says to anyone who questions him about this, that it one oral tradition in the royal family states that they descend from Benares, in India. 2° There is a legend in Brahmanical India which speaks of a Rajah who raised an army of Scythians and Kamputchaea, and this name Kamputchaea exists on a stamp of the current king. 3° We know that the Chinese maintained relations with the kings of Cambodia. Moreover, the Chinese annals mention an embassy accounting that in the year 20 before Christ the waters of the lakes bathed Angkor; therefore Angkor existed then. 4° The annals of Ceylon say that before the year 105 AD, the Kamputchaea or Cambodians invaded India and defeated the Indians.”]

King Norodom in the 1870s-1880s

“Le roi Norodom Ier, qui est âgé de 46 ans, a une taille au-dessous de la moyenne. Sous un front large et fuyant, brille un regard vif et curieux, miroir de son intelligence, car le roi passé pour être le plus habile de son royaume le reste do sa physionomie appartient au type cambodgien. D’ordinaire, Sa Majesté est très polie et très affable avec les Européens et surtout avec les officiers de toute arme qui viennent le voir. Dans la conversation, il saisit souvent le sens de la phrase de son interlocuteur avant que l’interprète lui en ait donné la traduction. Beaucoup de mots

de notre langue lui sont familiers, et peut-être affecte-t-il un peu quelquefoisde né point vouloir faire une réponse en français. […] « C’est bizarre, fit tout à coup Sa Majesté, la température s’élève de plus en plus. Il y a quelque soixante ans, paraît-il, au dire de mes vieux serviteurs, il faisait froid à Phnom-Penh à certaines époques de l’année mais, certes, les temps sont bien changés. J’ignore quelle en est la cause, et suis conséquemment tres embarrassé pour répondre là-dessus aux questions de certains de mes mandarins qui, beaucoup plus vieux que moi, ont pu constater ce changement. » J’écoutais avec attention la traduction de ces quelques mots, quand le Dr Hahn, me poussant légèrement du coude, me dit tout bas « Cherchez donc une raison à cela, et donnez-la au roi vous lui ferez grand plaisir. » « Vous n’y pensez pas, repris-je interloqué, quelle bonne raison voulez-vous que je donne ?.. Et comme il insistait et que le roi m’observait avec une vive curiosité, je bravais la situation à mes risques et périls et jetais à tout hasard l’explication suivante. Me tournant alors vers M. Faraut: « Veuillez, je vous prie, dire à Sa Majesté que nous avons pu remarquer en France des perturbations analogues survenues dans l’état atmosphérique, et que, dans certaines régions où la sécheresse persiste aujourd’hui, contrairement à ce qui se passait autrefois, d’aucuns attribuent l’absence des pluies aux nombreuses coupes de bois qu’on y fait. Si l’on rapproche l’absence des pluies du manqué de froid, né faudrait-il pas voir peut-être dans la production de ce phénomène la même cause ?»

Quand M. Faraut eut achevé, en souriant, cette tirade explicative à brûle-pourpoint, le roi eut un soubresaut et put s’écrier, en son langage « Eurêka M. Vidal a trouvé, M. Vidal a dit vrai. En effet, en telle et telle année, on fit pour construire tel et tel village (et ici le roi citait les localités) des coupes énormes. Les alentours de Phnom-Penh, qui étaient alors recouverts de grandes forêts, en sont complètement dépourvus aujourd’hui. J’ai souvent entendu dire cela et je suis très content de cette explication. Quand mes mandarins me redemanderont la chose, je leur répondrai ce que vient de me répondre M. Vidal, qui a dit vrai !»

[“King Norodom I, who is 46 years old, is of below average height. Beneath a broad, receding forehead, shines a lively and inquisitive gaze, a mirror of his intelligence, for the king is considered to be the most skillful in his kingdom; the rest of his physiognomy belongs to the Cambodian type. Ordinarily, His Majesty is very polite and very affable with Europeans and especially with the officers of all branches who come to see him. In conversation, he often grasps the meaning of his interlocutor’s sentence before the interpreter has translated it. Many words

of our language are familiar to him, and perhaps he sometimes affects a little not to want to give an answer in French. […] “It’s strange,” His Majesty said suddenly, “the temperature is rising higher and higher. Some sixty years ago, it seems, according to my old servants, it was cold in Phnom Penh at certain times of the year but, Certainly, times have changed. I do not know what the cause is, and am consequently very embarrassed to answer the questions of some of my mandarins who, much older than I, have been able to observe this change. ” I listened attentively to the translation of these few words, when Dr. Hahn, gently nudging me with his elbow, said to me in a low voice, “So look for a reason for this, and give it to the king, you will give him great pleasure.” “You are not thinking,” I continued, taken aback, “what good reason do you want me to give? … And as he persisted and the king observed me with lively curiosity, I braved the situation at my own risk and peril and threw out the following explanation at random. Turning then to Mr. Faraut: “Please, I beg you, tell His Majesty that we have been able to observe in France similar disturbances occurring in the atmospheric state, and that, in certain regions where the drought persists today, contrary to what happened in the past, some attribute the lack of rain to the extensive logging operations there. If we link the lack of rain to the lack of cold, shouldn’t we perhaps see the same cause in the production of this phenomenon?”

When Mr. Faraut finished, smiling, this explanatory tirade at the drop of a hat, the king gave a start and was able to exclaim, in his own language, “Eureka! Mr. Vidal has found it, Mr. Vidal spoke the truth. Indeed, in such and such a year, enormous logging operations were carried out to build such and such a village (and here the king cited the localities). The surroundings of Phnom Penh, which were then covered with large forests, are completely devoid of them today. I have often heard this said and I am very pleased with this explanation. When my mandarins ask me again, I will tell them what Mr. Vidal, who spoke the truth, just told me!”]

Au debut de la conversation,le roi nous avait offert des cigares, et je pus remarquer qu’il se faisait un véritable plaisir de nous présenter une allumette enflammée pour y mettre feu. De temps en temps et sur un signe, des femmes venaient apporter différents objets, des cigarettes entre autres, fabriquées dans le harem par les nombreuses prisonnières. Les femmes qui approchaient du roi en ce moment étaient certainement des premières favorites, fort remarquables d’ailleurs, autant qu’il m’en souvient. Quand nous eûmes fumé plusieurs cigares, la nuit venant, nous prîmes congé du roi, qui, loin de languir en notre société, cherchait à nous retenir davantage. Le roi actuel, dont l’avènement au trône eut lieu en juin 1864, reçut à cette époque une série de titres qu’on trouve en tête de bien des édits, documents ou actes ofliciels rédigés depuis à la Cour de Phnom-Penh. Cette longue suite de noms cependant né figure que dans les écrits qui ont une importance marquée, car le plus souvent on se contente de mentionner une partie de ces titres, que nous donnons ici en entier: Barômmà Néeth Prèa-Bat Somdach Préa Norôudâm Barômmà Reemà Tévàtana Kunnasa Santhorit Mahé Savora Thùppedèy Serey Sâurioûvông Norpùthapông Dâmrâng Réas Barômma Néeth Maha Kâmpoûchéa Thùppedintho Sappasèllapà Presàt Thu Sat That Satha Por Prùmma Mor Amnôi Chey Chéa Mahé Savaria Thùppedèy Ney Patha Pîchùl Sokala Kâmpoù Nachàhk Aka Maha Baras Réecht Vivatha Néa Térek Êk Audâm Barômmà Bapit Prèa Chau Krông Kâmpoûchéa Thùppedèy Chéa Ammechàs Chivit Leeuh Thbaûng. Voici quelle serait la signification qu’on pourrait attribuer à cette litanie: Celui qui est le suprême refuge, l’être aux pieds sacrés, Seigneur, personne illustre entre les grands, excellent, parfait Rama, descendant dos esprits célestes beau et glorieux fils du soleil. resplendissant conducteur des peuples, glorieux. illustre, parfait et sacré, empereur de l’immense capitale de Kâmpoûchéa qui est le maître des âmes placé au-dessus des têtes.

“Les titres du prince cadet, dit Jeanneau [Gustave Janneau, a French teacher who was a pioneer in Cambodian studies], sont pour le moins aussi emphatiques, et l’on y retrouve la même prétention traditionnelle à une origine divine, qui, depuis l’origine des sociétés humaines, a toujours chatouillé agréablement la vanité des rois enivrés de puissance. Malgré la diversité des formules hyperboliques qui encadrent le plus souvent cette étrange aberration, elle reste au fond toujours la même. Destinée à durer aussi longtemps que le pouvoir absolu, elle né disparaîtra qu’avec le dernier roi du dernier royaume, et se transmet sans varier, en dépit du temps et de la distance, de Sésostris au roi soleil, de Nabuchodonosor à Alexandre-Sabas, de Jules César à Norodom. […]

“Le roi est très curieux de sa nature entre autres choses, il s’intéresse ou paraît s’intéresser aux questions de notre politique et dela politique européenne. L’étude de l’astronomie, sur laquelle les Cambodgiens en général paraissent avoir quelques notions, a pour lui de grands attraits. Enfin, le temps qu’il n’emploie pas aux affaires de son royaume, le roi le passé dans son harem au milieu de ses femmes, à dormir ou à fumer l’opium. A ce propos, disons que le sommeil du roi est sacré malheur à qui se permettrait de réveiller par un bruit quelconque, fût-il involontaire, le monarque endormi.

[At the beginning of the conversation, the king had offered us cigars, and I could see that he took great pleasure in presenting us with a lit match to light them. From time to time, and at a sign, women came to bring various objects, cigarettes among others, made in the harem by the numerous prisoners. The women who approached the king at this moment were certainly early favorites, very remarkable ones, as far as I remember. When we had smoked several cigars, as night fell, we took leave of the king, who, far from languishing in our company, sought to keep us longer. The present king, whose accession to the throne took place in June 1864, received at that time a series of titles that are found at the head of many edicts, documents or official acts drawn up since then at the Court of Phnom Penh. This long sequence of names, however, only appears in writings which are of marked importance, because most often we are content to mention part of these titles, which we give here in full: Barômmà Néeth Prèa-Bat Somdach Préa Norôudâm Barômmà Reemà Tévàtana Kunnasa Santhorit Mahé Savora Thùppedèy Serey Sâurioûvông Norpùthapông Dâmrâng Réas Barômma Néeth Maha Kâmpoûchéa Thùppedintho Sappasèllapà Presàt Thu Sat That Satha Por Prùmma Mor Amnôi Chey Chéa Mahé Savaria Thùppedèy Ney Patha Pîchùl Sokala Kâmpoubli Nachàhk Aka Maha Baras Réecht Vivatha Néa Térek Êk Audâm Barômmà Bapit Prèa Chau Krong Kampouchea Thuppedeey Chea Ammechàs Chivit Leeuh Thbaûng. Here is the meaning that could be attributed to this litany: He who is the supreme refuge, the being with sacred feet, Lord, person illustrious among the great, excellent, perfect Rama, descended from celestial spirits, beautiful and glorious son of the sun. Resplendent leader of the peoples, glorious. Illustrious, perfect and sacred, emperor of the immense capital of Kampouchea, who is the master of souls placed above heads. [1]

“The titles of the younger prince,” says Jeanneau [Gustave Janneau, a French teacher who was a pioneer in Cambodian studies], “are at least as emphatic, and one finds in them the same traditional claim to a divine origin, which, since the beginning of human societies, has always pleasantly tickled the vanity of kings intoxicated with power. Despite the diversity of hyperbolic formulas that most often frame this strange aberration, it remains fundamentally the same. Destined to last as long as absolute power, it will disappear only with the last king of the last kingdom, and is transmitted without variation, despite time and distance, from Sesostris to the Sun King, from Nebuchadnezzar to Alexander Saba, from Julius Caesar to Norodom. […]

“The king is very curious by nature, among other things; he is interested, or appears to be interested, in questions of our politics and European politics. The study of astronomy, about which the Cambodians in general seem to have some notions, has great attractions for him. Finally, the time that he is not employed in the affairs of his kingdom, the king spends in his harem among his women, sleeping or smoking opium. In this connection, let us say that the sleep of the king is a sacred misfortune to anyone who would dare to wake the sleeping monarch by any noise, even involuntary.]

“Le mot Norodom n’est point le nom propre du roi actuel, c’est un de ses titres nombreux cités plus haut et dont la signification né saurait être mieux rendue que par la périphrase latine Magnus inter Magnos [should be “inter Magni’, ADB]. Pour pouvoir bien en rendre la prononciation, il devrait s’écrire Noroudam, en ayant soin de donner à la lettre (A) un son sourd se rapprochant de l’(O). Les jeunes princes cambodgiens ont un nom propre qu’ils perdent vers l’âge de la puberté, à l’époque où on leur rase la tête. Cette opération, qui forme étape dans leur existence, est une cérémonie qui s’accomplit avec pompe. Ce nom qu’on leur a donné étant enfant né doit plus leur être appliqué, et, si le prince devient roi, cette appellation, non seulement né doit plus lui être donnée, mais encore personne né peut la recevoir ni la prononcer sans être susceptible d’encourir la peine du rotin ou de l’emprisonnement. Il y a eu maints exemples Louchant ces faits et dans lesquels ces peines ont été infligées.

“Le nom propre de Norodom est Chrelâng, qui, dit Jeanneau, sert à désigner en langue cambodgienne un poisson d’une espèce fort commune auquel on n’appliqué ce nom Chrelâng que lorsqu’il est jeune, et qui prend successivement aux deux dernières périodes de sa croissance les noms de Trey-Khnoûch et de Trey-Prelûng. De ces trois noms, qui désignent un seul et même poisson, les deux derniers seulement peuvent être et continuent àêtre employés depuis l’avènement du roi actuel. […]

“Le harem contient, dit-on, près de deux cents femmes de nationalités diverses, et au milieu desquelles dominent les Siamoises. Ces femmes né sortent que très rarement. Deux ou trois fois dans l’année, à époques fixes, elles se rendent en voiture à la pagode; d’autre part, dans les jours de fêtes et lorsque Sa Majesté le veut bien, elles font partie de sa suite. Dans ces sorties, elles se parent de tous leurs bijoux et de leurs plus riches costumes. Beaucoup de ces malheureuses sont achetées à grand prix par des trafiquants attachés pour ce service à la personne du roi, ou quelquefois, mais d’une façon, tout exceptionnelle, il faut le dire, réquisitionnées et bien plus économiquement. […] Le roi a des gardiens pour son harem (les Kromowans), qui veillent jour et nuit et accompagnent toute personne, homme ou femme, qui par hasard, a obtenu le droit d’y entrer. Ce droit né résulte que d’un ordre du roi et devient fort rare pour les hommes.”

“The word Norodom is not the proper name of the current king, it is one of his numerous titles cited above and whose meaning could not be better rendered than by the Latin periphrasis Magnus inter Magnos [should be “inter Magni’, ADB]. To be able to correctly pronounce it, it should be written Noroudam, taking care to give the letter (A) a dull sound approaching the (O). The young Cambodian princes have a proper name which they lose around the age of puberty, at the time when their heads are shaved. This operation, which forms a stage in their existence, is a ceremony which is performed with pomp. This name which was given to them as children must no longer be applied to them, and, if the prince becomes king, this appellation, not only must no longer be given to him, but no one can receive it or pronounce it without being liable to incur the penalty of the rattan or imprisonment. There have been many examples of these facts and in which these punishments were inflicted.

“The proper name of Norodom is Chrelâng, which, says Jeanneau, is used in the Cambodian language to designate a fish of a very common species to which the name Chrelâng is applied only when it is young, and which successively takes the names Trey-Khnoûch and Trey-Prelûng during the last two periods of its growth. Of these three names, which designate one and the same fish, only the last two can be and continue to be used since the accession of the current king […].

“The harem contains, it is said, nearly two hundred women of various nationalities, among whom the Siamese predominate. These women go out only very rarely. Two or three times a year, at fixed times, they go by carriage to the pagoda; on the other hand, on festive days and when His Majesty so wishes, they are part of his retinue. On these outings, they adorn themselves with all their jewels and their richest costumes. Many of these unfortunate women are bought at great cost by traffickers attached to the king’s person for this service, or sometimes, but in a very exceptional way, it must be said, requisitioned and much more economically. […] The king has guards for his harem (the Kromowans), who watch day and night and accompany any person, man or woman, who by chance has obtained the right to enter it. This right results only from an order of the king and becomes very rare for men.”

[1] Unfamiliar with the abundance of honorific titles and epithets for Asian sovereigns, French visitors at the time often commented on King Norodom’s ones. In fact, King Norodom I held three major names during his reign and after his passing away: Norodom Prohmbarirak នរោត្ដម ព្រហ្មបរិរក្ស, Ang Reacheavoddey អង្គរាជាវតី, and, posthumously, Preah Karuna Preah Sovannakot ព្រះករុណាព្រះសុវណ្ណកោដ្ឋ.

Bakus

[Note: The authors have been inspired by previous studies authored by Etienne Aymonier, Gustave Janneau and Adhémard Leclère.]

“Il est une autre espèce de gardiens [du palais] qui portent le nom de Bakous ce sont les gardiens des cendres des rois et de l’épée sacrée du royaume. Ils sont les conseillers de Sa Majesté pour le cérémonial à observer dans les grandes fêtes. Ils né se rasent point la tête et portent leurs cheveux longs et retroussés, réunis en un petit chignon au-dessus de la nuque. Ils né se marient qu’entre eux et constituent une petite caste vivant dans l’enceinte du palais royal. Jusqu’à ce jour, il a été à peu près impossible d’obtenir de leur part aucun renseignement on croit qu’ils

professent la religion brahmanique et qu’ils sont venus de l’Inde à la suite des Kampouchéas ou premiers Cambodgiens. C’est alors que, n’ayant pas voulu embrasser le Bouddhisme, ils auraient été constitués, par les rois cambodgiens, dépositaires des vieux usages de l’Inde.”

[Royal Cremation] “Les cendres des rois cambodgiens crémés sont conservées dans des urnes d’or, sous un pavillon à ce consacré, situé dans l’enceinte du palais royal. Une ou deux fois par an, les cendres du père du roi actuel sont promenées en grande pompe à travers les rues de la capitale. Un mandarin portant sur ses bras un faisceau de rotins ouvre la marche, suivi à quelques pas de trois autres mandarins portant des faisceaux de sabres. Un orchestre complet vient ensuite, précédant le brancard sur lequel est l’urne en or qui contient les cendres, à l’abri d’un grand parasol jaune, ce brancard est porté par six individus. Enfin, et fermant le cortège, viennent encore trois mandarins porte-sabres et un mandarin porte-rotins. Tout cet ensemble défile entre deux rangées de Bakous tenant à la main un fil de coton blanc non interrompu, que les mauvais esprits, les Nactas, né sauraient franchir.”

[“There is another class of guardians [of the palace] who bear the name of Bakus; they are the guardians of the kings’ ashes and of the sacred sword of the kingdom. They are His Majesty’s advisors for the ceremonial to be observed during major festivals. They do not shave their heads and wear their hair long and curled, gathered into a small bun above the nape of the neck. They marry only among themselves and constitute a small caste living within the confines of the royal palace. To this day, it has been almost impossible to obtain any information from them. It is believed that they profess the Brahmanic religion and that they came from India following the Kampouchéas or first Cambodians. It was then that, not having wanted to embrace Buddhism, they were supposedly constituted, by the Cambodian kings, custodians of the ancient customs of India.” [Royal Cremation] “The ashes of cremated Cambodian kings are preserved in golden urns, under a dedicated pavilion located within the royal palace. Once or twice a year, the ashes of the current king’s father are paraded with great pomp through the streets of the capital. A mandarin carrying a bundle of rattans on his arms leads the way, followed a few paces later by three other mandarins carrying bundles of sabers. A full orchestra follows, preceding the stretcher bearing the golden urn containing the ashes. Sheltered by a large yellow parasol, this stretcher is carried by six individuals. Finally, and closing the procession, come three more saber-bearing mandarins and a rattan-bearing mandarin. This entire ensemble parades between two rows of Baku holding an unbroken white cotton thread, which the evil spirits, the Nactas, cannot cross.”]

[During Water Festival] “Pendant les trois jours que durent ces fêtes, et à deux reprises (14, 15 et 16 octobre et novembre), le roi n’habite plus son palais. Il reste jour et nuit sur le fleuve, dans des bateaux dont l’avant représente une énorme tête de dragon toute dorée et la gueule entr* ouverte. Ces barques, d’une certaine grandeur, sont garnies de toitures et fort richement ornementées. Autour d’elles, se tiennent, dans des maisons élevées sur radeaux de bambous, les femmes de Sa Majesté. Deux petites pirogues montées par des Bakous habillés tout de rouge et dont la coiffure ressemble à nos bonnets de nuit, sont mouillées à 60 mètres des barques royales et séparées l’une de l’autre par une distance de 150 mètres environ; un fil de coton blanc est tendu d’une de ces pirogues à l’autre. C’est durant ces trois jours qu’ont lieu toutes sortes de jeux sur les eaux du fleuve, où l’on peut voir flotter des pirogues de 40 mètres de longueur, creusées dans un seul tronc d’arbre et montées par une cinquantaine de rameurs.[…] Or, le fil de coton blanc qui relie les barques des Bakous n’est point là seulement pour arrêter les eaux, mais aussi et surtout pour accumuler contre lui toutes les choses mauvaises et nuisibles, tous les Nactas de la création, qui, réunis à la fin du troisième jour et chassés par les huées du peuple et des bateliers, finissent par prendre la fuite dès qu’on vient à le couper.”

“During the three days that these festivals last, and on two occasions (October 14, 15 and 16 and November), the king no longer lives in his palace. He remains day and night on the river, in boats whose front represents an enormous dragon’s head all gilded and their mouths half open. These boats, of a certain size, are furnished with roofs and very richly ornamented. Around them, His Majesty’s wives are kept in houses raised on bamboo rafts. Two small canoes manned by Bakus dressed all in red and whose headdress resembles our nightcaps, are anchored 60 meters from the royal boats and separated from each other by a distance of about 150 meters; a white cotton thread is stretched from one of these canoes to the other. It is during these three days that all kinds of games take place on the waters of the river, where one can see float canoes 40 meters long, dug out of a single tree trunk and manned by about fifty oarsmen. […] Now, the white cotton thread that connects the boats of the Bakus is not there only to stop the waters, but also and above all to accumulate against it all the bad and harmful things, all the Nactas of creation, which, gathered at the end of the third day and chased away by the jeers of the people and the boatmen, end up taking flight as soon as it is cut.”

Note: more about Bön Om Tuk (Water Festival) around that time.

Elephants

“Les éléphants domestiques du Cambodge sont presque en totalité la propriété du roi, qui en possède environ deux cents. Ils vivent en troupe à deux journées de marche de la capitale, sous la conduite de nombreux gardiens et au milieu de gras pâturages. Au moindre appel du Ministre de la Guerre, qui en est tout spécialement chargé, ces animaux viennent à Phnom-Penh. Chacun d’eux a son guide propre, son père nourricier, qu’il connaît et lequel a grand empire sur lui. Ce sont les cornacs, esclaves héréditaires qui forment caste dans le royaume, comme nous le verrons plus loin, qui sont exclusivement attachés à la conduite, à la garde et à l’éducation des éléphants. Leur bagage instructif se compose de quelques mots et d’un bâton affectant les formes suivantes:

[“The domestic elephants of Cambodia are almost entirely the property of the king, who owns about two hundred of them. They live in herds two days’ walk from the capital, under the guidance of numerous keepers and in the middle of rich pastures. At the slightest call from the Minister of War, who is specially charged with them, these animals come to Phnom Penh. Each of them has his own guide, his foster father, whom he knows and who has great influence over him. It is the mahouts, hereditary slaves who form a caste in the kingdom, as we will see later, who are exclusively attached to the management, care and education of the elephants. Their instructive baggage consists of a few words and a stick taking the following forms:]

Mahut stick, drawing in Roux-Vidal publication.

“1. Un manche D en bois ou quelquefois en hane contournée et à côtes; 2. Une armature en fer A, dans laquelle s’emmanche le morceau ou la poignée de bois. La pointe B, légèrement quadrangulaire à son milieu, sert à activer la marche de l’animal, la pointe C, également quadrangulaire à son milieu, est très acérée elle sert à le retenir ou à le contenir. Cette pointe s’apphque entre la base des sinus frontaux et la naissance de la trompe. Ces courbes gracieuses rappellent vaguement, et en tout cas excessivement amoindries, les courbes brusques et gigantesques d’une trompe d’éléphant. On né voit rien d’extraordinaire à ce que ces peuples, ornant de trompes d’éléphants les toits des pagodes et des demeures royales, aient voulu donner à cet instrument cette forme particulière, rappelant par ses contours une partie du corps de l’animal, la tête, sur laquelle ils agissent pour l’éduquer.

“Mais ce crochet de fer né suffirait point pour faire comprendre à l’éléphant les diverses manoeuvres qu’il peut avoir à exécuter dans l’exercice qui lui incombe. La voix du cornac supplée alors à l’impuissance de l’objet, et voici de quoi se compose son mince vocabulaire. Quand le conducteur prononce sur un ton nasillard le mot Haôu, l’animal s’arrête; ce mot est l’équivalent de Stop. Il est exclusivement réservé pour les éléphants et né s’emploie dans aucun autre cas. La langue cambodgienne est pleine de mots réservés à tel ou tel usage. Lorsqu’il y a sur le sol un obstacle, un trou, une ornière, un passage difficile ou une racine d’arbre en travers de la route, le cornac prononce le mot Chung. Ce mot signifie pied. Le cornac, en le prononçant, entend dire à son animal Fais attention à tes pieds Si l’obstacle est mobile et d’un poids convenable, l’éléphant le saisit avec sa trompe et l’écarté de la voie. Si l’objet est immobile, il sonde également avec sa trompe et, s’avançant avec lenteur, le contourne.

“Enfin il existe un troisième et dernier mot, mais le plus important c’est le mot Daï. Il signifie doigt, bras, avant-bras. Quand un cornac le prononce, c’est de l’organe de préhension, du doigt que le proboscidien porte au bout de sa trompe et de sa trompe elle-même, qu’il veut parler. C’est lorsqu’une branche, trop grosse pour être écartée par son crochet ou coupée par le couperet que tout cornac porte à sa ceinture, menace de faire tomber la cage et la personne qu’elle abrite, que ce mot est jeté. L’éléphant cherche d’abord à contourner l’obstacle mais si son conducteur, comprenant qu’il faut en passer par là, le presse en ajoutant au mot Daï l’action de son croc, alors il lève la tète, saisit la branche et la casse. S’il n’est pas assez fort pour arriver à ce résultat, le cornac suivant (dans le cas où il y a plusieurs éléphants) fait ajouter les efforts de son animal à ceux du premier un troisième survient encore s’aligner s’il le faut, et il est peu de branches qui résistent à de pareilles tractions.

Vers neuf heures et demie nous atteignons, au sortir d’un bois, une belle plaine étendant jusqu’à l’horizon un immense tapis de verdure, au milieu duquel s’élèvent de loin en loin comme les oasis d’un petit désert, de beaux massifs d’arbres. Çà et là quelques troupeaux de buffles et de boeufs animent cette riche nature, rappelant en tous points un de nos gracieux paysages de Normandie.”

[“1. A handle (D) made of wood, or sometimes of a curved and ribbed handle; 2. An iron frame (A), into which the piece or handle of wood is fitted. Point (B), slightly quadrangular in the middle, serves to encourage the animal to walk; point ©, also quadrangular in the middle, is very sharp and serves to restrain or contain it. This point is applied between the base of the frontal sinuses and the base of the trunk. These graceful curves vaguely recall, and in any case excessively diminished, the abrupt and gigantic curves of an elephant’s trunk. There is nothing extraordinary in the fact that these people, adorning the roofs of pagodas and royal residences with elephant trunks, wanted to give this instrument this particular shape, recalling by its contours a part of the animal’s body, the head, on which they act to educate it.

“But this iron hook would not be enough to make the elephant understand the various maneuvers that it may have to perform in the exercise that falls to it. The voice of the mahout then makes up for the impotence of the object, and this is what his meager vocabulary is composed of. When the driver pronounces in a nasal tone the word Haôu, the animal stops; this word is the equivalent of Stop. It is exclusively reserved for elephants and is not used in any other case. The Cambodian language is full of words reserved for this or that use. When there is an obstacle on the ground, a hole, a rut, a difficult passage or a tree root across the road, the mahout pronounces the word Chung. This word means foot. The mahout, in pronouncing it, intends to say to his animal: Watch your feet. If the obstacle is mobile and of a suitable weight, the elephant seizes it with its trunk and moves it out of the way. If the object is stationary, it also probes with its proboscis and, moving slowly forward, skirts around it.

“Finally, there is a third and final word, but the most important is the word Daï. It means finger, arm, forearm. When a mahout pronounces it, it is the organ of grasping, the finger that the proboscidean carries at the end of its trunk and its trunk itself, that he wants to speak. It is when a branch, too large to be pushed aside by its hook or cut by the cleaver that every mahout carries at his belt, threatens to bring down the cage and the person it shelters, that this word is thrown out. The elephant first tries to get around the obstacle but if its driver, understanding that it must go through this, presses it by adding to the word Daï the action of its hook, then it raises its head, seizes the branch and breaks it. If it is not strong enough to achieve this result, the next mahout (in the case where there are several elephants) adds the efforts of his animal to those of the first. A third still occurs align themselves if necessary, and there are few branches that can withstand such pulls.

Around nine thirty, coming out of a wood, we reach a beautiful plain stretching to the horizon with an immense carpet of greenery, in the middle of which rise here and there, like the oases of a small desert, beautiful clumps of trees. Here and there, a few herds of buffalo and oxen enliven this rich nature, recalling in every way one of our graceful Normandy landscapes.”]

The ‘Nacta’ [Neak-ta]

“Le Bouddhisme suivi au Cambodge est mêlé d’une foule de croyances superstitieuses qui ont donné lieu de tout temps à la création et à la pratique de certains cultes. C’est ainsi qu’après la croyance aux serpents est venue la croyance aux esprits, aux diables et aux génies après le culte des serpents, le culte des Nactas. Les Nactas sont nombreux et de toute espèce. Ce sont les gardiens invisibles des eaux, des bois, des montagnes, de l’air, du feu, de la maladie, etc., etc., esprits presque toujours malfaisants aux yeux de ces peuplades, et qu’une crainte issue de

l’ignorance dut engendrer autrefois: Tïmor fecit Deus. Né pouvant s’expliquer les causes de tel ou tel effet, l’homme dut en attribuer le pouvoir à quelque être surnaturel et tout-puissant. Le besoin inné de savoir le comment et le pourquoi de tout ce qui lui arrive, devait forcément l’amener à invoquer l’inconnu pour lui faire expliquer les phénomènes ignorés jusque-là. Il est certain que le premier qui, comme Horace, entendit un coup de tonnerre dans un ciel serein né se rendit aucun compte de ce bruit formidable, et, s’il en vit les effets, il dut les attribuer a un être essentiellement supérieur et fort, capable de tirer parti de quelqu’un de ses actes pour lors, une divinité était toute trouvée.

“De l’idée d’apaiser les esprits malfaisants et de se les rendre propices, vinrent une foule de pratiques plus ou moins surprenantes, destinées, soit à exprimer la gratitude, soit à conjurer les effets de quelque vengeance. L’ignorance des faits et de leurs causes, réunie aux superstitions créées et entassées d’âgo en âge, a, depuis des siècles et des siècles, enveloppé l’intelligence grossière de ces peuples de fictions tellement étranges, que c’est à peine si aujourd’hui cette intelligence, dégrossie et guidée par le flambeau de la raison et de nos sciences positives, parvient à déchirer le voile qui masquait sa vue. Au coin d’un bois, à l’extrémité d’une île ou sur la berge d’un fleuve, on voit une petite niche toujours à l’endroit le plus ombragé, le plus agréable et le plus frais. C’est afin qu’il n’ait pas trop chaud, qu’il y soit bien et qu’il s’y plaise, qu’on choisit ce lieu, le plus favorable pour le Nacta. Cette divinité, qui est représentée par un morceau de bois, un caillou, un objet informe ou quelquefois par rien du tout, est censée habiter là. C’est là qu’on vient lui faire des offrandes, brûler de petites chandelles, lui porter du riz, des gâteaux, des poules et souvent un cochon rôti tout entier. En ces lieux, on se garderait bien de parler trop haut, ou en des termes irrévérencieux, du Nacta on le vénère parce qu’on le craint, et ce culte n’a d’autre mobile que de se le rendre propice en écartant ses maléfices.”

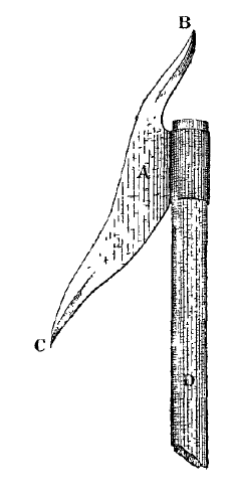

Roux & Vidal’s itinerary, January 1882. It seems they particularly wanted to visit the prehistoric site of Somrong-Sen, which had been discovered a few years earlier by Jean Moura, who collected there some artefacts later given to the Toulouse Museum (France). [source: gallica.bnf.fr]

Roux & Vidal’s itinerary, January 1882. It seems they particularly wanted to visit the prehistoric site of Somrong-Sen, which had been discovered a few years earlier by Jean Moura, who collected there some artefacts later given to the Toulouse Museum (France). [source: gallica.bnf.fr]

“Buddhism in Cambodia is mixed with an array of superstitious beliefs that have always given rise to the creation and practice of certain cults. Thus, after the belief in snakes came the belief in spirits, devils, and genies, after the cult of snakes, the cult of the Nactas [neak ta]. The Nactas are numerous and of all kinds. They are the invisible guardians of water, woods, mountains, air, fire, disease, etc., etc., spirits that are almost always malevolent in the eyes of these peoples, and that a fear born of ignorance must have engendered in the past: Timor fecit Deus. Unable to explain the causes of this or that effect, man had to attribute the power to some supernatural and all-powerful being. The innate need to know the how and why of everything that happens to him must necessarily lead him to invoke the unknown to explain the phenomena. unknown until then. It is certain that the first person, like Horace, who heard a clap of thunder in a clear sky, was completely unaware of this formidable noise, and if he saw its effects, he must have attributed them to an essentially superior and strong being, capable of taking advantage of someone’s actions; for then, a deity was all there.

“From the idea of appeasing evil spirits and making them propitious, came a host of more or less surprising practices, intended either to express gratitude or to ward off the effects of some revenge. Ignorance of facts and their causes, combined with superstitions created and piled up from age to age, has, for centuries and centuries, enveloped the crude intelligence of these peoples in such strange fictions that today this intelligence, refined and guided by the torch of reason and our positive sciences, can hardly tear away the veil that masked its view. At the corner of a wood, at the end of an island or on the bank of a river, we see a small niche always in the most shaded, most pleasant and cool place. It is so that it is not too hot, so that it is comfortable there and likes it, that this place is chosen, the most favorable for the Nacta. This divinity, which is represented by a piece of wood, a pebble, a shapeless object or sometimes by nothing at all, is supposed to live there. It is there that people come to make offerings to him, burn small candles, bring him rice, cakes, chickens and often a whole roast pig. In these places, people would be careful not to speak too loudly, or in irreverent terms, of the Nacta; they venerate him because they fear him, and this cult has no other motive than to make him propitious by removing his evil spells.”

Main photo: Portrait of King Norodom I by John Thomson.

Tags: Phnom Penh Royal Palace, legends, Protectorate, King Norodom I, elephants, religion, 1880s, 1870s, prehistoric settlements, India, Bakus, Brahmanism, water festival, neak ta