This substantial study gives us a rare access to Cambodia-related literature in Thai language, as well as a stimulating exploration of Khmer archives by a Thai writer who is fluent in Khmer language. It also let us hear the voices of “little, ordinary people”, how they saw the political events in Cambodia at the time, and how they reacted to the growing presence of France.

In his research through numerous archives — National Archive of Cambodia (NAC) in Phnom Penh, National Library of Thailand (NLT) and National Archives of Thailand (NAT) in Bangkok, Archives Nationales d’Outremer (ANOM), Bibliotheque Municipale d’Alencon BAM, Archives de la Bibliotheque de France (ABF), Archives EFEO and Bibliotheque de la Societe Asiatique (BSA) in France –, the author unearthed many texts reflecting Cambodian popular poems, songs and tales, in particular the following one, which to our knowledge had never been commented before.

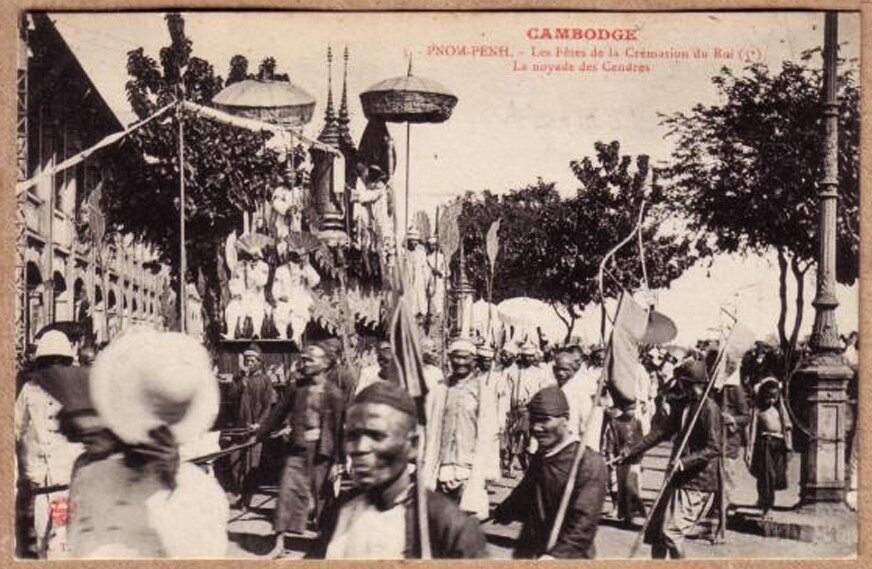

“The Capture of Phnom Penh” in 1898 [p 174 – 9]

The prophetic sayings that spread over the region before and during the uprising of Takeo in 1898 were based on tŭmneay literature, in both oral and written forms, Thi Phung. It was kẫmnap, literally “poem,” entitled “une chanson en caractère cambodgien au sujet de la prise de Phnom Penh [A song in Cambodian Character on the Capture of Phnŭm Pénh],” [ANOM RSC 404, file no. 47, doc. no. 6. However, I found it instead in folder of file no. 46.] hereafter La prise de Phnom Penh. It was not a tŭmneay but rather a historical narrative. However, as noted above, tŭmneay is both a narrative of the future (prophecy) and the past (history). The past was used to prophesy the future. To this extent, words and ideas extracted from La prise de Phnom Penh could be turned to be prophetic sayings.

La prise de Phnom Penh was written in seven-syllable metre, which was very popular among court poets of the nineteenth century. It was comprised of 54 stanzas; the first stanza is a preamble, the next ten stanzas are a eulogy to sacred beings, and most of the rest are a narrative about what happened in the capture of Phnŭm Pénh in 1884 and its aftermaths. It should be noted that it was said that there is another record of the incident of June 17, 1884,

written by Khmer author and called Sastra lom vӗang, “the manuscript concerning of the encirclement of the royal palace.” It belonged to the Library of the Buddhist Institute in Phnŭm Pénh. After 1968, it disappeared, however [quoted from Khin Sok]. Hence, La prise de Phnom Penh is probably the only surviving nineteenth-century narrative about the incident of June 17, 1884, from an indigenous point of view. Unsurprisingly, La prise de Phnom Penh narrates a different story of the incident in comparison to that of the French. [ADB: Here’s the account in Paul Branda’s Ça et là, Cochinchine et Cambodge, L’ame Khmère, Ang-Kor, 1886, p 8 – 9):]

Around 4.45 a.m. of June 17, 1884, French troops surrounded the royal palace. At 5.30 a.m., the governor of Cochinchina Charles Thomson, accompanied by staff officers and a detachment of twelve marines, appeared in the royal chambers and woke up King Norodom. Almost four hours later, Thomson emerged with a new treaty already signed by the king. French Commodore Paul Réveillère, who was the Commander of the Navy in Cochinchina from August 1884 to August 1886, told lively anecdotes about what had happened in the royal chamber. The governor then opened a window overlooking the river, and said to the unfortunate monarch,

‘You must choose: accept the treaty or abdicate. May your Majesty decide.’

‘And if I do not want either to deal or to abdicate.’

‘Looks at this plume of smoke, Your Majesty,’ replied the governor, by pointing a war corvette in front of the palace, ‘the Alouette is under steam; she is ready to leave, to refuse the treaty is to be taken off and carried on board.’

From time to time the Second King put his nose at the meeting, as if to say, ‘I am here. Count on me.’

‘And what will you do with me aboard the Alouette?’

‘That is my secret.’

Norodom bent his head and signed.

The corvette Alouette, carried with her 120 French marines, 150 Vietnamese tirailleurs and 7 officers from Cochinchina, had anchored in the Quatre Bras since June 1884. In La prise de Phnom Penh, after the eulogy, the following is stated,

12/ The world turned to immense sufferings.

13 When the king, our dear lord, precious of our life,

Occupied the absolutely glorious throne,

For a full twenty-five years,

O, our Monseigneur, our jewel, our divine power.

14 The King, on

The ninth day of the waning moon of the month of Chés,

The year of Monkey, the sixth year of the decade,

Turned to be furious.

Then, from stanzas 16 to 19, the French presence in Phnŭm Pénh is described. But it seems to be a description of the arrival of the French Protectorate in 1863 rather than the arrival of the French troops in 1884. Place (Ŭdŏng and Phnŭm Pénh, which became the residence of the King and the capital city since 1866) and time (time between 1863 and 1884) are compressed and merged to prelude the capture of Phnŭm Pénh on June 17, which emerges in stanza 20: “The King was stuck in the royal palace surrounded by the French, amid their strong grip.” The trespass of the governor Thomson and his company, and also the dramatic scene in the king’s chamber, are not presented in La prise de Phnom Penh. Norodom was locked in his palace but he could call the Ŏbarach, Chav Khŭn, and Oknha Brâsaoe Sŏrĭvong to meet him in order to consult about how to deal with the kingdom’s crisis. King Norodom said to his half-brother the Ŏbarach Sisowath,

23 ‘There was the general that led troops,

‘He strongly wanted to fight with me,

‘[The troops] had surrounded my residence, I was woken up.

‘So, my brother, what do you think?

24 ‘He asked from me land and people,

‘Taking care of all administrations as a regent,

‘Desire to establish himself as a King.

‘My brother, what is your opinion, or are you thinking about giving up?’

25 The Mӗaha Ŏbarach,

Knowing about the power [of the French], is afraid to be disgraced,

If he opposes, he is afraid to be poor,

‘My dear King, give him all!’

Sisowath, who was promoted as Ŏbarach in 1870, was favored by the French administrators. It seems the French prepared to put him on the throne if Norodom denied signing the new treaty. Advice of Chav Khŭn (informal term referring to high-ranking official) was not different from that of Sisowath: “[We] cannot resist [the French], Your Majesty” (stanza 26). Then, Oknha Brâsaoe Sŏrĭvong was called to appear before the king.

34 Prosor [ADB: ?] lifted his hands to respectfully inform the king,

‘Your Majesty, my overlord,

‘Resisting and conflicting [with the French] will fail,

‘Like an egg that is held tightly in the hand.

35 ‘Will it survive? Never!,

‘[They] don’t know the word mercy, my dear Your Majesty,

‘They have already reached into the hearth [of the kingdom],

‘My dear Your Majesty, give them all!’

We know with certainty that, however, from 5.30 a.m. to 9.15 a.m. of June 17, 1884, Norodom was surrounded by the French in his chamber. His secretary and interpreter Col de Monteiro was taken out of his chamber after the new treaty was read to him. Perhaps, another Khmer that presented in the royal chamber was Son Diep who acted as an

interpreter for the Governor Thomson. Sisowath was probably in the royal palace, “put[ting] his nose” into the king’s chamber during the meeting between the king and the French. Thus, Sisowath the Ŏbarach, Chav Khŭn, and Oknha Brâsaoe Sŏrĭvong never had an audience with Norodom to give him advice in the morning of June 17, 1884. The meetings and advice described in La prise de Phnom Penh are fictional, but they have some real foundation as their basis. Those imaginary dialogues are followed by these following lines, which are worth

quoting at length:

36 The king heard Brâsaoe said so,

He feft uneasy in his stomach,

He was disheartened by misfortune,

As heard from tŭmneay, it seemed all was already given to them.

37 Dignitaries who depended on the king’s merit,

Avoided [to do their duties], or did it carelessly,

They did not think about the country,

Looked for and embraced the danger, sought for their opportunity.

38 They always conscripted reas to work, without compassion.

They smoked, ate, and drank alcohol, without conscience.

They corrupted and cheated in the name of merit and power.

Some needed to be Krâ(la)haom, Vӗang.

39 Made wrong to right, without thinking over it.

Some established new kinds of tax and revenue

To collect much money from all reas.

They did not consider affairs of the country.

40 They oppressed Khmer, Chinese, and Cham,

Forbade the poor to unite together.

Fishing in river, lake and pond, to make a living,

was all taxed.

41 Officials intensively checked and collected rice tax,

And head tax. There was no money left over.

Silk tax. Fishing net tax. Island cultivation tax.

There was no saving left over.

42 Thus, the country faced unbearable sufferings.

The coming of barăng made the country unrest.

Officials in Phnom Penh did not fight.

Instead, it was a business of reas in provinces.

La prise de Phnom Penh not only criticizes the authorities up to the Ŏbarach, but the king as well.

48 O! Kamphuchea,

It used to be in complete darkness,

Lost all, left nothing.

(Then,) France came to nurture and rebuild (Cambodia).

49 The King and the barăng made friend with each other,

[Their relation was] full of love and amity.

For a long time, the reigning monarchs depended on,

The merit and glory of Luong Bârŭmkaot [the posthumous title of King Duong].

50 Years passed,

(The king) did not act to oppose [the French].

.….…..

The last verse of the last stanza (stanza 54) of La prise de Phnom Penh that reads “That’s all we remember” reveals that it is a copy of previously existing text(s), whether written or oral. Original text(s) must have been composed after the capture of Phnom Penh on June 17, 1884. It was possibly composed during the countrywide uprising of 1885 – 1886, but stanzas 48 to 53 might be added later.

Somehow La prise de Phnom Penh was in the hands of partisans of the uprising of 1898. We do not know how it was used during the uprising. But it is not surprising if some stanzas or words –particularly stanzas 37 to 44, which criticizes and attacks the ruling élites by revealing their infidelity, immorality, and misconduct– would be selected to address to people before and during the uprising of 1898. These stanzas are timeless. They can be simply used as a

weapon of people against the indigenous Establishment. The collaboration of the king and the French (stanzas 48 to 53) granted enough legitimacy and reason to uprise against the rules of the king and the French.

Aside from reality-based imagination, another source of La prise de Phnom Penh was tŭmneay, as referred in the fourth verse of stanza 36. We do not know which tŭmneay was used as a source for La prise de Phnom Penh. But we do know that there was at least Neaḥ kpuon Inda duaṃnāy (EFEO P9) that contains stories concerning the capture of Phnom Penh in 1884. Neaḥ kpuon Inda duaṃnāy (EFEO P9) claims that it is words of the Buddha given shortly before

his death. It begins with a prediction that the sāsanā will last for 5,000 years. Then, a history of the rise and decline of the sāsanā is briefly narrated. The first three stories are a universal history of the sāsanā: the building of stūpa‑s to enshrine the Buddha’s relics by King Thammasokka [Dhammasokaraja, or Asoka] in B.E. 220, the defeat of King Malintradhiraja [Milinda, or Menanader] by Nagasena in B.E. 620, and the destruction of the sāsanā in B.E. 1420 by Tmĭl andethey [a.w. Tmĭl terathey], or Tamil heretics, who were later defeated by King Aphai Tossakamani [Abhaya Duṭṭhagāmaṇī]. The next three stories concern the legendary history of Cambodia: the copying of Buddhist canons in Lanka in B.E. 1750 by Buddhagōsa who later brought those copies back to enshrine in Angkor Wat,151 the enthronement in B.E. 2030 of the king Tossavong who later became a leper and was cursed by Mӗaha Ruesei [the

great hermit], and the chaos in B.E. 2085, which can be seen as a continuation of decline that began after the curse of Mӗaha Ruesei.

When the august sasâna reached 2427 years old, the year of the Monkey, the sixth year of the decade, on Tuesday, the ninth day of the waning moon, the month of Chés, in the early morning. Tmĭl andethey will come to capture the country. This date is exactly the same as that in stanza 14 of La prise de Phnom Penh. It is June 17, 1884. Obviously, Tmĭl andethey refers to the French. Contrary to La prise de Phnom Penh, Put tŭmneay does not narrate in details, either fact or fiction, about the capture of Phnŭm Pénh in 1884.

Then, three predictions are provided. Prӗahbat Angkŭlireach will come to suppress Tmĭl andethey in the year of the Pig, the ninth year of the decade, which is circa 1887. Four nĕak sel will fight against each other in “tonlé buon mŭkh,” the Quatre Bras, in the year of the Dragon, the fourth year of the decade, which is circa 1892. At last, from the year of the Monkey, the eighth year of the decade, which is circa 1896, to the year of the Pig, the first year of the

decade, which is circa 1899, Assajit Thera, who is the future Buddha Metteyya, will come to “uplift” the sāsanā.

The exact dating of Put tŭmneay is not known, but it must have been composed after the capture of Phnom Penh in 1884. Or at least, it was edited after the capture of Phnom Penh in 1884 by adding the incident into an existing text.

Apart from mentioning the capture of Phnŭm Pénh on June 17, 1884, another thing La prise de Phnom Penh and Neaḥ kpuon Inda duaṃnāy (EFEO P9) share together is a new mode of explanation about causes of occurrences and things that already happened and will happen, which also is a new form of criticism against authorities.

About the moral portence of these tales, the author comments further on [p 191]:

Deviances in tŭmneay occurred in the Buddhist notions of cyclical time, i.e. time was conceptualized as continually reoccurring cycles. It is close to what Walter Benjamin calls the “messianic time,” the non – linear conception of time in which past and future occurs simultaneously in an instantaneous present. In the realm of cyclical/messianic time, “what will be” is not yet “what is.” Everything is determined. (Thus, tŭmneay, as well as astrological knowledge, are not a prediction, but a revelation). No one cannot be blamed for severe calamity that happened, happening, and will happen. But there is a sign of change in Neaḥ kpuon Inda duaṃnāy (EFEO P9), where unprecedented motifs appear: “[King, nobilities, and reas] obsessed in gambling, drinking alcohol, and smoking opium.” This sign can also be seen in the second verse of stanza 38 of La prise de Phnom Penh, “They smoke, eat, and drink alcohol, without conscience.”

These moral motifs were not timeless and placeless, but they were things that happened at a specific time and location, which was Cambodia under French Protectorate, or more specifically, Cambodia after the capture of Phnŭm Pénh on June 17, 1884. These moral motifs were a critique against immoral behaviors of Khmer authorities, which caused the decline of the kingdom. The capture of Phnŭm Pénh was the most obvious representation of the decline. On the other hand, the incident gave birth to a new chapter of tŭmneay literature. The best example of that change is Duṃnāy knuṅ sārasnār (EFEO P43). Similar to La prise de Phnom Penh, Duṃnāy knuṅ sārasnār (EFEO P43) was written in seven – syllable metre. It is comprised of 65 stanzas. The first stanza gives the date of composing, which is September 27, 1901. Then, deviances were described.

Commoners and kings: the tax issue

“Without income [from the people], there could be no expenditure [for the government],” stated Oknha Prăk, a former interpreter trained in France, then a chavvay srŏk (governor), in his book, Notre argent [Our Money]. “The income from “l’ impôt personnel,” the head tax or prăk pŭan [pon?] thlai reachka khluon (called thlai reachka in brief), which was a direct tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual,38 was about 27 per cent of the government income in 1910: “Income from prăk pŭan thlai reachka khluon that Khmer and Cham-Chvea (Chams and Malays) have to pay is 530,000 riel. Dẫmriet (head tax on foreigners) collected from Yuon (Vietnamese) was 45,000 riel. Dẫmriet collected from Chinese and Indians was 190,000 riel.” Thlai reachka in 1910 was 2.70 riel for liable men of 20 – 60 years old. It was reduced for disabled and old men. At least 196,000 Khmer and Cham-Chvea paid head tax. With the inclusion of foreigners, who were also subjects of the king, the number of reas who paid head tax must have been greater. Contrary to Oknha Sŏttântâbreychea (Ĕn, 1859 – 1924)[Ind Suttantaprija], a highly respected Pāli scholar, reformist, and modernist, who regarded thlai reachka as “reach plĭ (sacrifice to the king),” which implied that paying head tax was nothing but a duty that the reas had to discharge in order to show their loyalty and gratitude to their king– Oknha Prăk implicitly accepted that the reas were an elementary force behind the progress of the country. “Our money” was “reas’ money,” he stated. Without reas there would not have been enough money to “enrich the srŏk khmae (the Khmer country) and the Khmer reas (the Khmer ordinary people).”

Notre argent was a literary prapaganda like Bândăm Ta Meas mentioned above. Ironically, until the Cambodian Independence in 1953, it is perhaps only in these two French literary prapaganda that the ordinary people were referred to as the narrator and the maker of history. However, the ordinary people mentioned in Notre argent were reduced to numbers and statistics. They were nameless and voiceless. In Bândăm Ta Meas, its authorship remains questionable because several stories mentioned in there were not general knowledge and were beyond the knowledge even of the élite. Moreover, Meas’ experience was very typical. It means Meas as the ordinary people and his name might be substituted with any ordinary people and any name without making any change in the core message, which is the glorification of the Khmer kings, and the savior-like quality of the French colonizers. Thus, Meas was nameless. In short, the ordinary people in Notre argent and Bândăm Ta Meas were the collective and anonymous mass.