Albeit a French socialite connected to the highest levels of colonial power-that-be — her grand father, Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat, had overseen ‘Indochina” for seven years as Minister of Navy and Colonies (1860−1867) — the author shows in this account her genuine interest in local cultures and mores.

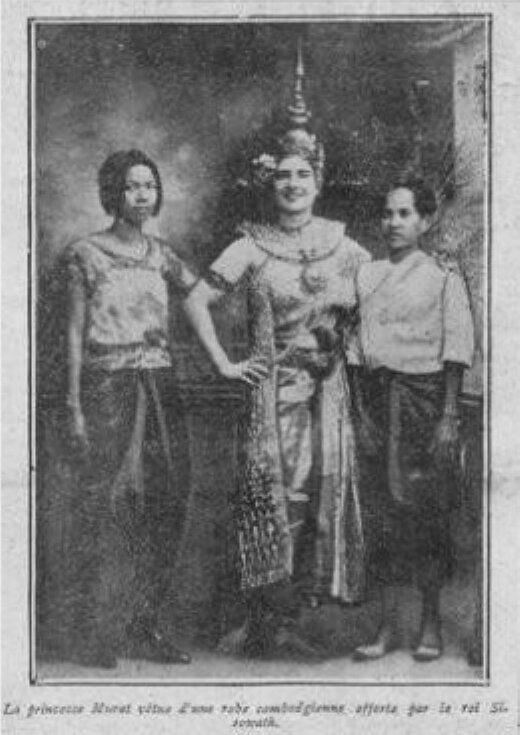

As a woman — and one conscious of her good looks –, her description of Luang Prabang’s maidens is endearing, far from the oggling-self-conscious testimonies from male travelers at the time. Her husband, Prince Achille Murat, shot a film about the travel that we are still trying to locate. They went to remote places in Laos, the Tran-Ninh highland, about 400 kms from North Vietnam by road.

Celebrations at Wat Mai

“C’est, parait-il, au mois de novembre qu’il faudrait venir ici pour assister dans le Wat-Mai, ”la pagode royale”, à la curieuse fête des Grands Serments. Le roi, porté sur une chaise élevée, arrive lentement au milieu d’un magnifique

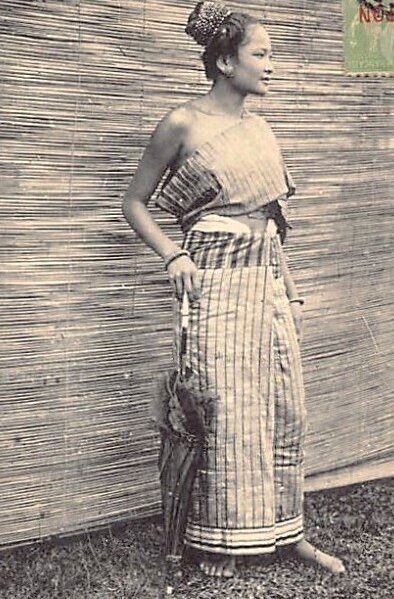

cortège de costumes chatoyants, d’éléphants richement caparaçonnés et de parasols blancs à sept étages. Puis, dans la sombre pagode remplie de cierges et de fleurs, devant le Pra-Bang apporté d’Angkor, le Bouddha vénéré couvert de feuilles d’or, par la piété des fidèles, les Laotiens jurent fidélité au roi de Luang-Prabang et à la République Française, en plongeant dans l’eau lustrale la pointe de leurs lances, de leurs sabres et de leurs flèches. On nous parle aussi de la joyeuse incinération qui a eu lieu dernièrement, à la mort du second roi. C’est une fête très joyeuse, une occasion de réjouissances pour tout le monde ; le Laotien sourit toujours, même devant la mort. Tout, du reste, est occasion de fête, à Luang-Prabang. Fête des oreilles : le rire des jeunes filles, les pou-saos, la voix grave du gong qui égrène les heures sur la colline sacrée, la plainte mélancolique du Khêne et la mélodie joyeuse des cymbales et des gongs de l’orchestre laotien. Fête des yeux : le divin paysage, les fleurs si variées, le soleil sur les claires écharpes et les robes jaunes des bonzes, et surtout les silhouettes harmonieuses des femmes. Celles de Luang-Prabang sont justement réputées pour leur beauté. Souvent grandes, toujours sveltes, les yeux à peine bridés et la démarche incomparable, elles se revêtent du sine, la jupe cylindrique en soie et coton, striée de fils d’or ou d’argent, qui les moule dans un fourreau rouge ou violet, depuis la taille jusqu’aux chevilles. Les seins ambrés sont à peine voilés par une écharpe rose ou bleue, mauve, verte ou orange.” [“Apparently, it is in November that we should come here to attend the curious festival of the Great Oaths in Wat-Mai, “the royal pagoda”. The king, carried on a high chair, arrives slowly in the middle of a magnificent procession of shimmering costumes, richly caparisoned elephants and seven-tiered white parasols. Then, in the dark pagoda filled with candles and flowers, in front of the Pra-Bang brought from Angkor, the venerated Buddha covered with gold leaves, through the piety of the faithful, the Laotians swear loyalty to the king of Luang-Prabang and to the French Republic, by plunging the tips of their spears, their sabers and their arrows into the lustral water. We are also told of the joyful cremation which took place recently, on the death of the second king. It is a very joyful part, an occasion of rejoicing for everyone; Laotian people always smile, even in the face of death. Everything else, in Luang-Prabang, is an occasion for celebration. Festival of ears: the laughter of young girls, the pou-saos, the deep voice of the gong which ticks off the hours on the sacred hill, the melancholy complaint of the Khêne and the joyful melody of the cymbals and gongs of the Laotian orchestra. A feast for the eyes: the divine landscape, the varied flowers, the sun on the clear scarves and yellow dresses of the monks, and above all the harmonious silhouettes of the women. Those of Luang-Prabang are famous for their beauty. Often tall, always slender, with barely slanted eyes and an incomparable gait, they wear sine, the cylindrical skirt in silk and cotton, streaked with gold or silver thread, which molds them into a red or purple sheath. , from the waist to the ankles. Amber breasts are barely veiled by a pink or blue, mauve, green or orange scarf.”]

Siam, Angkor, Prah Keo, Laotian princesses

“Jadis, la « Cité du Santal », capitale d’un royaume puissant, contenait soixante-deux pagodes, dont la splendeur et la richesse, en 1666, faisaient l’émerveillement d’un voyageur hollandais. Maintenant, la plupart des Bouddhas,

souvent mutilés, dominent tristement des monceaux de pierres. Au début du XIXe siècle, le roi de Siam né pardonna jamais au roi de Vientane d’avoir refusé de lui accorder en mariage la main d’une de ses filles, renommée pour sa beauté. Il l’enleva de force, ainsi que le Prah Kéo, le Bouddha d’Emeraude, palladium des Laotiens, aujourd’hui la gloire de Bangkok; quelques années plus tard, il rasa complètement la ville brillante et ses vieilles pagodes. […] Pendant une demi-heure, la berge continue à s’effondrer par intermittences et nous cherchons vainement le mystère du méchant poisson. Le lendemain, un des bateliers nous apporte, triomphant, une boîte d’allumettes illustrée à l’effigie d’un…dragon. C’est lui. Décidément, nous né sommes pas éloignés des légendes où Rothisen [??], prince d’Angkor, remontant le Mékong sur une embarcation, sans doute pareille à la nôtre, vint chercher pour épouse Neang Kangrey, fille du Lang Xang, le pays des Millions d’Eléphants …” [“A long time ago, the “Sandalwood City”, capital of a powerful kingdom, hosted sixty-two pagodas, whose splendor and wealth, in 1666, amazed a Dutch traveler. Now, most of the Buddhas, often mutilated, sadly dominate mounds of stones. At the beginning of the 19th century, the King of Siam never forgave the King of Vientane for refusing to grant him the hand of one of his daughters, renowned for her beauty. He removed her by force, as well as the Prah Keo, the Emerald Buddha, palladium of the Laotians, today the glory of Bangkok; a few years later, he completely razed the shining city and its old pagodas. […] For half an hour, the bank continues to collapse intermittently and we search in vain for the mystery of the evil fish. The next day, one of the boatmen brings us, triumphantly, a box of matches illustrated with the image of a… dragon. It’s him! Certainly, we are not far from the legends where Rothisen [??], prince of Angkor, going up the Mekong on a boat, undoubtedly similar to ours, came to seek for wife Neang Kangrey, daughter of Lang Xang, the country of Millions of Elephants…”]