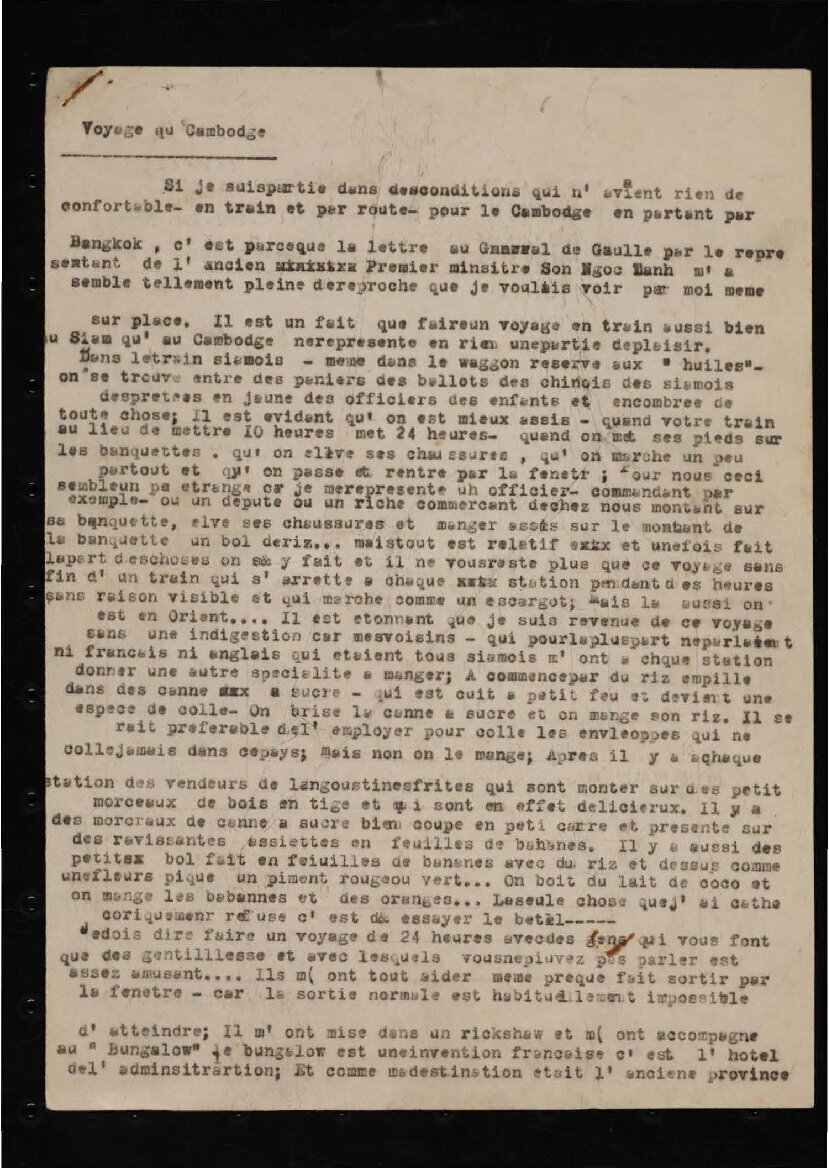

Voyage au Cambodge, 1945-1946

by Germaine Krull

A powerful description of post-World War II Cambodia, with a French administration in turmoil and a suffering population.

- Publication

- Germaine Krull Estate Archive | Courtesy of Ms. Petra Steinhardt, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany.

- Published

- January 2nd, 1946

- Author

- Germaine Krull

- Pages

- 9

- Language

- French

pdf 2.0 MB

“C’était un temps déraisonnable, on avait mis les morts à table/On faisait des châteaux de sable, on prenait les loups pour des chiens” [It was a foolish time, We had sat the dead at the table/We were building sand castles, we mistook wolves for dogs]: the louche atmosphere of post-conflict so well evoked by poet Louis Aragon permeates this travelogue-mission report in 1945 Cambodia by photographer Germaine Krull, an independent observer who had been mandated by Charles de Gaulle to visit French Indochina at the end of World War II.

Concluding her report on Jan 2, 1946, three years before King Sihanouk was to start an open campaign for independence (reached on Nov. 9, 1953) and a few weeks before the young King’s first visit to France (to the Saumur military academy, the German-born globetrotter doesn’t conceal her critical view of the French administrative officers, noting that ‘almost all of them have been collaborationists’ [to the Pétain régime and the Nazis]. She arrived in Cambodia in October 1945, precisely when the French administration was officially restored. In January 1946, autonomy within the French Union was granted to Cambodia.

Traveling by train from Bangkok with the help of the British legation, Germaine Krull’s first contact with Cambodia occurs in Pursat: “Dans ce train, les regards [des Cambodgiens] sont bien sombres pour nous, et je n’ai pas vu une seule personne nous faire un sourire.” [On this train, [Cambodians] cast quite hostile glances on us, and I didn’t see one single person smile at us.] There, she finds the “really small” French Resistance mission, including “un vieux copain d’Alsace” [an old chap from the Alsatian front]. Nearby, Japanese prisoners await their fate in a camp — Japan has surrendered in August.

In September 1945, Germaine Krull was in Saigon, photographying General Leclerc — for the third time, since she had shot the French military leader in 1943 in Brazzaville and on 30 Oct 1944 in Strasbourg, on both occasions with De Gaulle –, trying to assuage the irascible Sir Douglas Gracey, commander of the Allied forces, and predicting the collapse of the colonialist power. During these few months, she wrote no less than five substantial “tapuscrits” [typescripts] on the Indochina political and military situation.

Cambodian notabilities seem to her really dishearthened by the French stubborness in limiting Cambodian ‘autonomy’ and perpetuating the old administration: “On nous remet á la place d’un conseiller quatre qui arrivent avec tout un personnel, nous revoyons exactement les memes gens, ceux qui nous ont fait tellement de mal pendant les années de l’amiral Decoux, on nous remet les memes policiers…” [Instead of one adviser we now get four, who come up with a whole staff, we see exactly the same people back, those who hurt us so much during the years of Admiral Decoux, we are given the same police officers…] Another pundit will tell Germaine: “Il n’y a qu’une seule solution: renvoyer sur un bateau tous les Francais qui n’ont pas été dans la Résistance et en faire venir d’autres!” [There is only one solution: to send back on a boat all the French who were not in the Resistance, and bring others in!]

The French Resistance emissary did not seem to have met in Phnom Penh — “tres jolie petite ville avec beaucoup de verdure, de belles maisons et des rues pleines de vie, mais celles-ci sont principalement chinoises” [very nice little city with lots of trees, beautiful houses and streets that are full of life, yet mostly Chinese] — with Prince Sisowath Monireth ស៊ីសុវត្ថិ មុន្នីរ៉េត (25 Nov 1909, Phnom Penh – September 1975, executed by the Khmer Rouge), the Sihanouk’s uncle who had just took the post of prime minister from nationalist insurgent Son Ngoc Thanh. But she reports harsh critics against “the ambitious Monireth and the king, who have promised us independence yet do not care about us.”

“L’atmosphere generale de Phnom Penh est détestable”, remarks the author; “tout le monde espionne tout le monde. Les Cambodgiens sont indicateurs pour les Francais, pour les Anglais, pour les nationalistes, pour le parti de Monireth, pour les Annamites” [The general atmosphere in Phnom Penh is just odious; everyone spies on everyone. The Cambodians are indicators for the French, for the English, for the nationalists, for the party of Monireth, for the Annamites”]. And after a difficult trip back, she reckons to be happy to go back to “peaceful Bangkok”.

Photo: ‘A Royal Patrol in 1945’, with King Sihanouk in white (source: Khmer Issarak)

Tags: French Indochina, World War II, post-colonial Cambodia, Cambodian independence, Vichy

About the Author

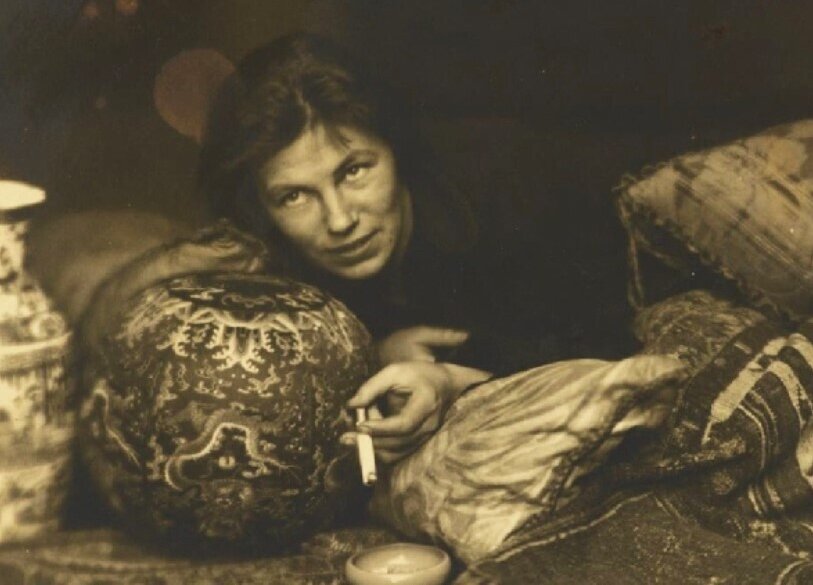

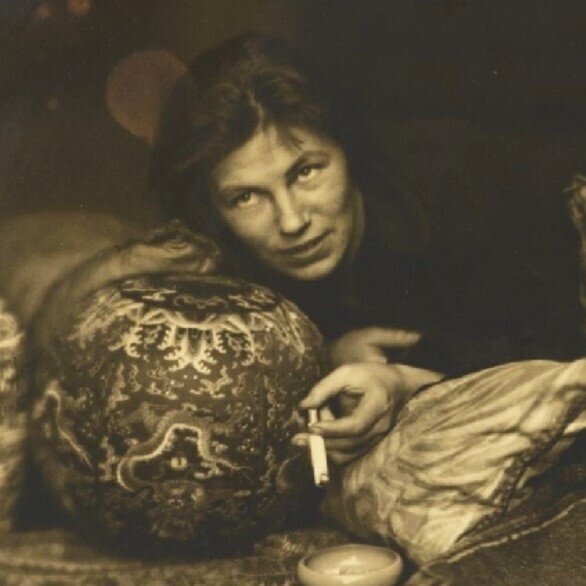

Germaine Krull

Germaine Luise Krull (20 November 1897, Posen-Wilda (then in Germany, now Poznan, Poland) – 31 July 1985, Wetzlar, Germany) was an avant-garde photographer, political activist, and avid traveler who beautifully captured Khmer temples in the 1960s before settling for a while in Tibet in her ongoing search for spirituality and a better world.

A free-thinker who questioned the patriarcal order — with the approval of her own father — from a young age, she attended the the Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie, a photography school in Munich, with the influence of Frank Eugene’s teaching of pictorialism, and opened her own studio there in 1918, portraying prominent artists such as Kurt Eisner, Rainer Maria Rilke, Friedrich Pollock, and Max Horkheimer.

Inclined to communist activism, she was harceled by police in Germany and Austria, traveled to Bolshevik Russia in 1921 with lover Samuel Levit, was imprisoned and expelled from there. She moved to Berlin, — where she created a series of nude photos with a quite explicit lesbian message — Amsterdam — where she met filmmaker Joris Ivens, with whom she contracted later a marriage of convenience — and Paris, where her ‘modernist’ style was remarked by surrealist circles and where she befriended artists such as photographers Man Ray ans André Kertész, artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay, and writers Colette, André Gide, Jean Cocteau or André Malraux. In her much-acclaimed portfolio Métal (1928), a 64 black-and-white dramatic shots in which she captured metallic architectural structures, “the essentially masculine subject of the industrial landscape”, in particular the Eiffel Tower. It is there that she portrayed writer and traveler Titayna with her Buddha head.

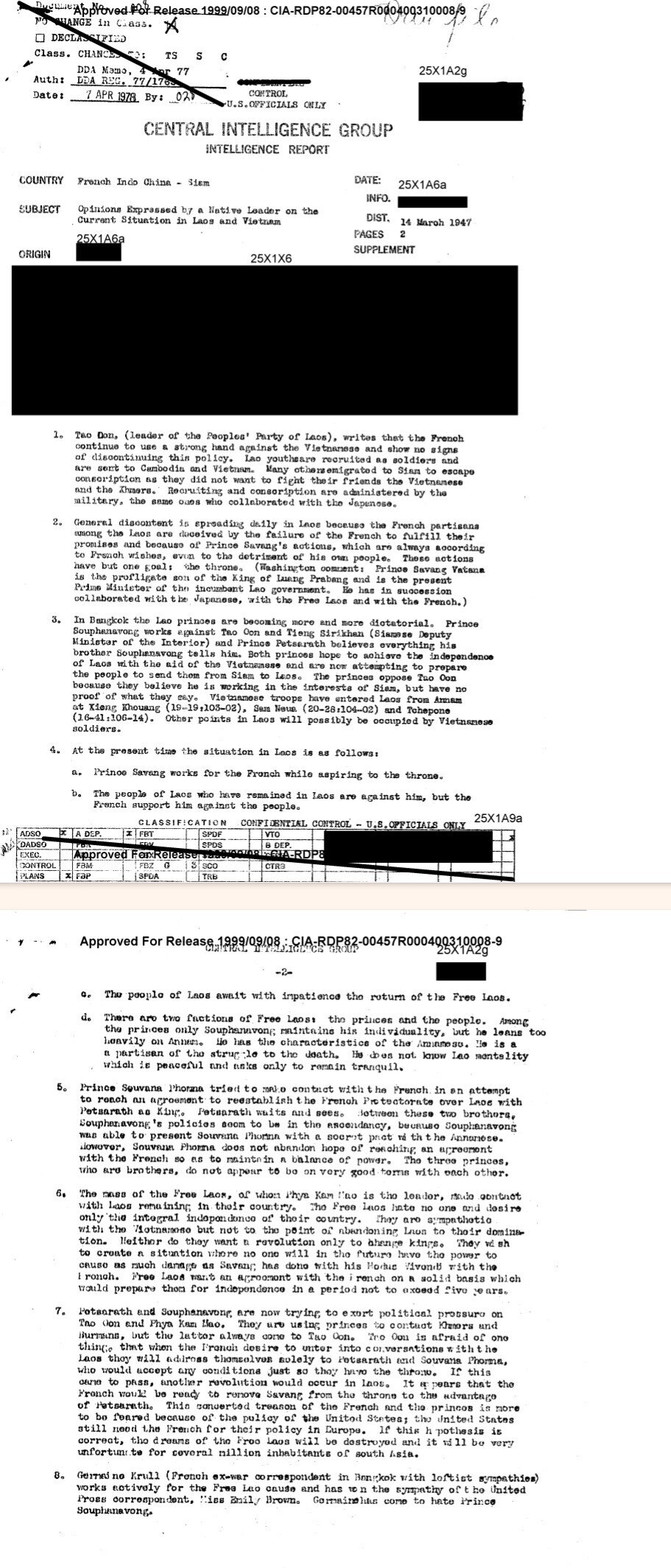

Living in Monte-Carlo in 1935 – 1940, Germaine Krull kept contributing to major photo magazines, travel and fiction books. Fleeing collaborationist France, she escaped to Brazil, French Equatorial Africa, Algeria, and actively contributed to the Resistance, capturing military action in France in 1944 – 1945. Her proximity to Malraux — they were working on a book about the sculptural and architectural art of Southeast Asia that never materialized — led to her involvement with the Gaullist movement. In her autobiography, she reported that the last time she saw Malraux in Paris — more precisely at La Lanterne, Malraux’s residence in Versailles –, “j’ai laissé plus de 1500 photos chez André, et elles y sont toujours!” [I left more than 1,500 photos at André’s, and they’re still there!] [1]. She went to Southeast Asia, first Laos, then Thailand and Cambodia in 1946 as a war correspondent and a representative of the French Resistance, and was spotted as such by the American CIA, for instance in this confidential dispatch.

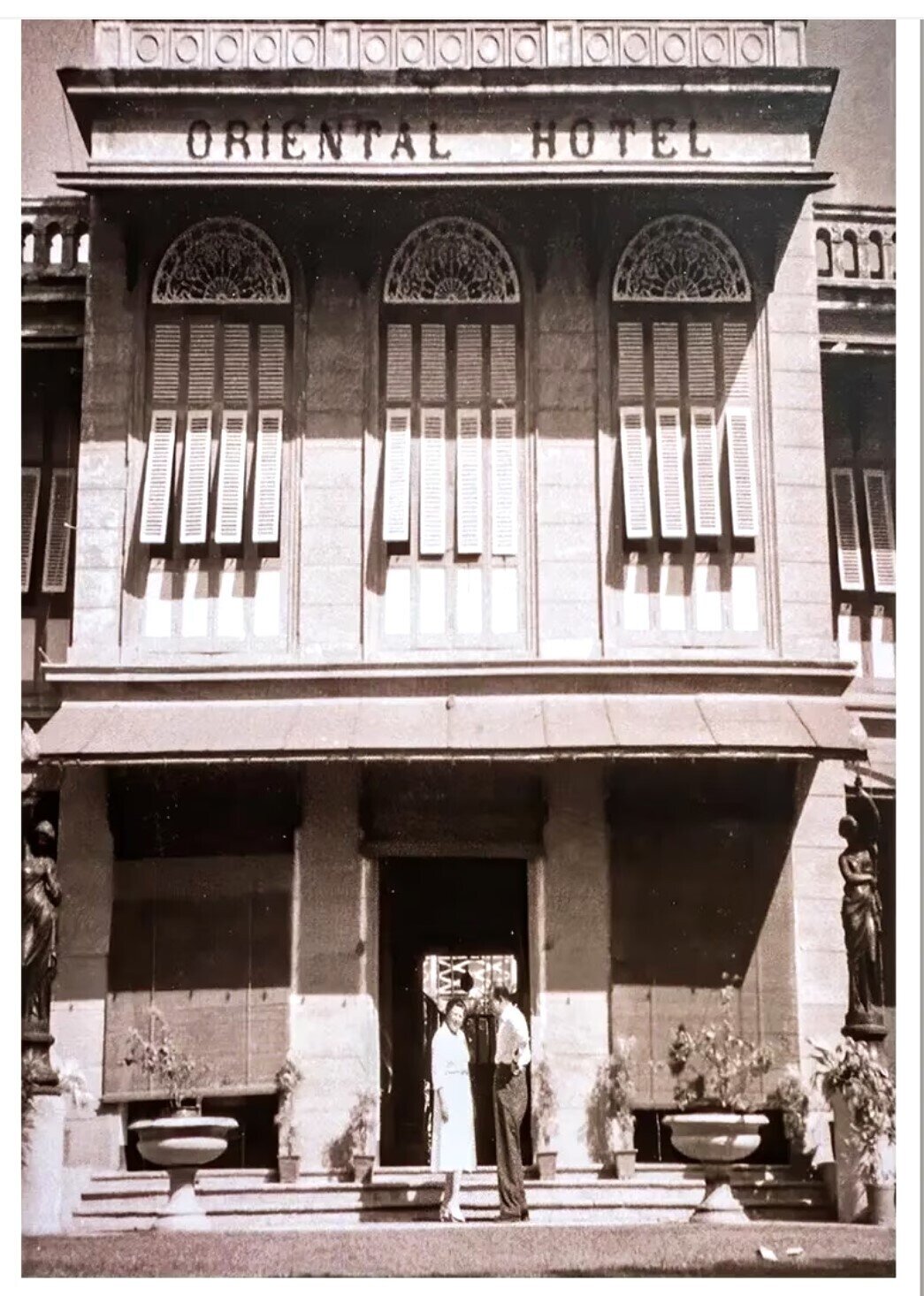

With famous designer Jim Thompson, she decided to remodel and refurbish the derelict Oriental Hotel in Bangkok — which was to become the Mandarin Oriental –, and in spite of many disagreements with Thompson remained its co-owner until 1966. She designed the now iconic Bamboo Bar, and slowly but surely led the hotel to grow from the Japanese Officers Club it had been turned into during World War II, and then to a transit hospitality center for anti-fascist activists, to a high-end establishment. [Read a complete and richly illustrated saga of the hotel by Wild’n’Free Diary.]

Meanwhile, she collaborated to three photo and text books about Thailand, and traveled frequentely to Angkor, photographying then lesser-known temples such as Pre Rup or Preah Khan. 268 of these remarkable documents are kept at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, within her archives donated by her heirs. Angkor Database wishes to make more accessible Krull’s unique contribution to the photographic documentation of Angkor Wat and other Khmer Temples.

Later on, Germaine Krull went briefly back to Paris, then moved to North India, where she embraced the Sakya teaching of Tibetan Buddhism. Her late work reflects her lifelong interest in Buddhist art and dance, both themes that had inspired her so profundly in Angkor. Her final major photographic publication was the 1968 book Tibetans in India, including a portrait of the Dalai Lama.

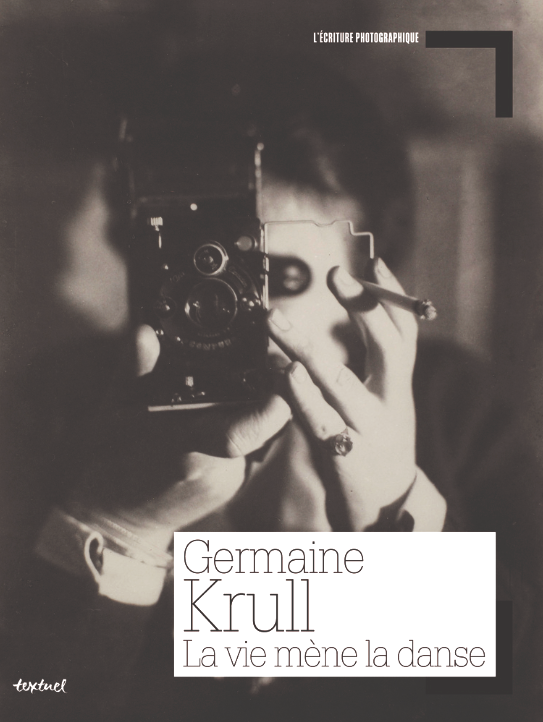

[1] Germaine Krull, La vie mene la danse, ed. Francoise Denoyelle, Textuel, Paris 2015 and 2019 [out of print], p 397. The editor added that she asked Madeleine Malraux (7 April 1914, Toulouse – 10 January 2014, Paris) about these photographs in 2001, but the pianist and concertist who had been Malraux’s companion from 1944 to 1966 said she had no idea of this collection’s whereabouts.

- Main publications: Métal, Paris: Librairie des arts décoratifs, 1928. (New facsimile edition published in 2003 by Ann and Jürgen Wilde, Köln.) | 100 x Paris, Berlin-Westend: Verlag der Reihe, 1929. | Études de Nu, Paris: Librairie des Arts Décoratifs, 1930. | with Raúl Lino and Ruy Ribeiro Couto, Uma Cidade Antiga do Brasil, Ouro Preto, Lisboa: Edições Atlântico, 1943.| Chiengmai, Bangkok: Assumption Printing Press, 1955. | with Dorothea Melchers, Bangkok: Siam’s City of Angels, London: R. Hale, 1964. | with Dorothea Melchers, Tales from Siam, London: R. Hale, 1966. | Tibetans in India, Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1968. | Posthumous autobiography: La Vita Conduce la Danza, Firenze: Filippo Giunti, 1992. ISBN 88−09−20219−8 (La vie mène la danse or “Life Leads the Dance”, translated into Italian by Giovanna Chiti.); La vie mène la danse (L’écriture photographique), ed. Francoise Denoyelle, Paris : Textuel editions, 2015. ISBN 978−2−84597−522−4.

- Among Germaine Krull’s contributions to literary work: Bucovich, Mario von, Paris, New York: Random House, 1930. | Colette. La Chatte, Paris: B. Grasset, 1930. | Nerval, Gérard de, and Germaine Krull, Le Valois, Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1930. | Claude Farrère, La Route Paris-Biarritz, Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1931. | Morand, Paul, and Germaine Krull, Route de Paris à la Méditerranée, Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1931. | Simenon, Georges, and Germaine Krull, La Folle d’Itteville, Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1931. | André Suarès, Marseille, Paris: Librairie Plon, 1935. | Vailland, Roger, La Bataille d’Alsace (Novembre-Décembre 1944), Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1945.

- Films: Six pour dix francs (France, 1930) | Il partit pour un long voyage (France, 1932)

- References: MacOrlan, Pierre, Germaine Krull: Photographes Nouveaux, Paris: Gallimard, 1931. | Rosenblum, Naomi, A History of Women Photographers, 2nd edition, New York: Abbeville Press, 2000. ISBN 0−7892−0658−7. | Baker, Kenneth. “Germaine Krull’s Radical Vision / Photographer’s Work Featured at SFMOMA”, San Francisco Chronicle, 15 April 2000. | “Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print 1919 – 1939”, Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1999. ISBN 84−8026−125−0. | Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn, Germaine Krull: Fotografien 1922 – 1966, Köln: Rheinland-Verlag, 1977. ISBN 3−7927−0364−5. | Bouqueret, Christian, and Moutashar, Michèle, Germaine Krull: Photographie 1924 – 1936, Arles: Musée Réattu, 1988. | Sichel, Kim, From Icon to Irony: German and American Industrial Photography, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995. ISBN 1−881450−06−6.; Germaine Krull: Photographer of Modernity, The MIT Press, 1999, ISBN 0−262−19401−5.; “Germaine Krull and L’Amitié Noire: World War II and French Colonialist Film”, in Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place, ed. Eleanor M. Hight and Gary D. Sampson, London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0−415−27495−8.; “Germaine Krull à Monte-Carlo [Germaine Krull: the Monte Carlo Years]”, Montréal: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, 2006, ISBN 2−89192−306−5. | Kosta, Barbara. “She was a Camera”, Women’s Review of Books, volume 17, issue 7, pages 9 – 10, April 2000. | Specker, Heidi, Bangkok — Heidi Specker Germaine Krull im Sprengel-Museum Hannover, 9. Oktober 2005 bis 25. Juni 2006. Zülpich: Albert-Renger-Patzsch-Archiv, 2005. ISBN 3−00−017658−6. | Bertolotti, Alessandro, Books of Nudes, New York: Abrams, 2007. ISBN 978−0−8109−9444−7. | Dumas, Marie Hélène. Lumières d’Exil, Paris: Gallimard and Éditions Joëlle Losfeld, 2009. ISBN 978−2−07−078770−8. (French novelization of Germaine Krull’s life.) | Roth, Andrew, ed., The Open Book: a History of the Photographic Book from 1878 to the Present, Göteborg, Sweden: Hasselblad Center, 2004. | “Portrait of Hedonist with Glasses Half Empty”, The Gazette (Montréal), 30 December 2006. | Frizot, Michel, Germaine Krull, Paris : Hazan editions, 2015. ISBN 978−2−7541−0816−4. (Catalog of “Germaine Krull (1897−1985)”, Jeu de Paume Museum Exhibition, 2015).

- Latest and Upcoming Exhibitions: “Germaine Krull– The Return Of An Avant-Gardist”, The Jim Thompson Art Centre & The Goethe Institute, Bangkok, June 2022. | “Germaine Krull and Southeast Asia”, Bangkok, September 2023.