Kампучия восставшая из пепла [Cambodia Risen From the Ashes]

by Evgeny V. Kobelev

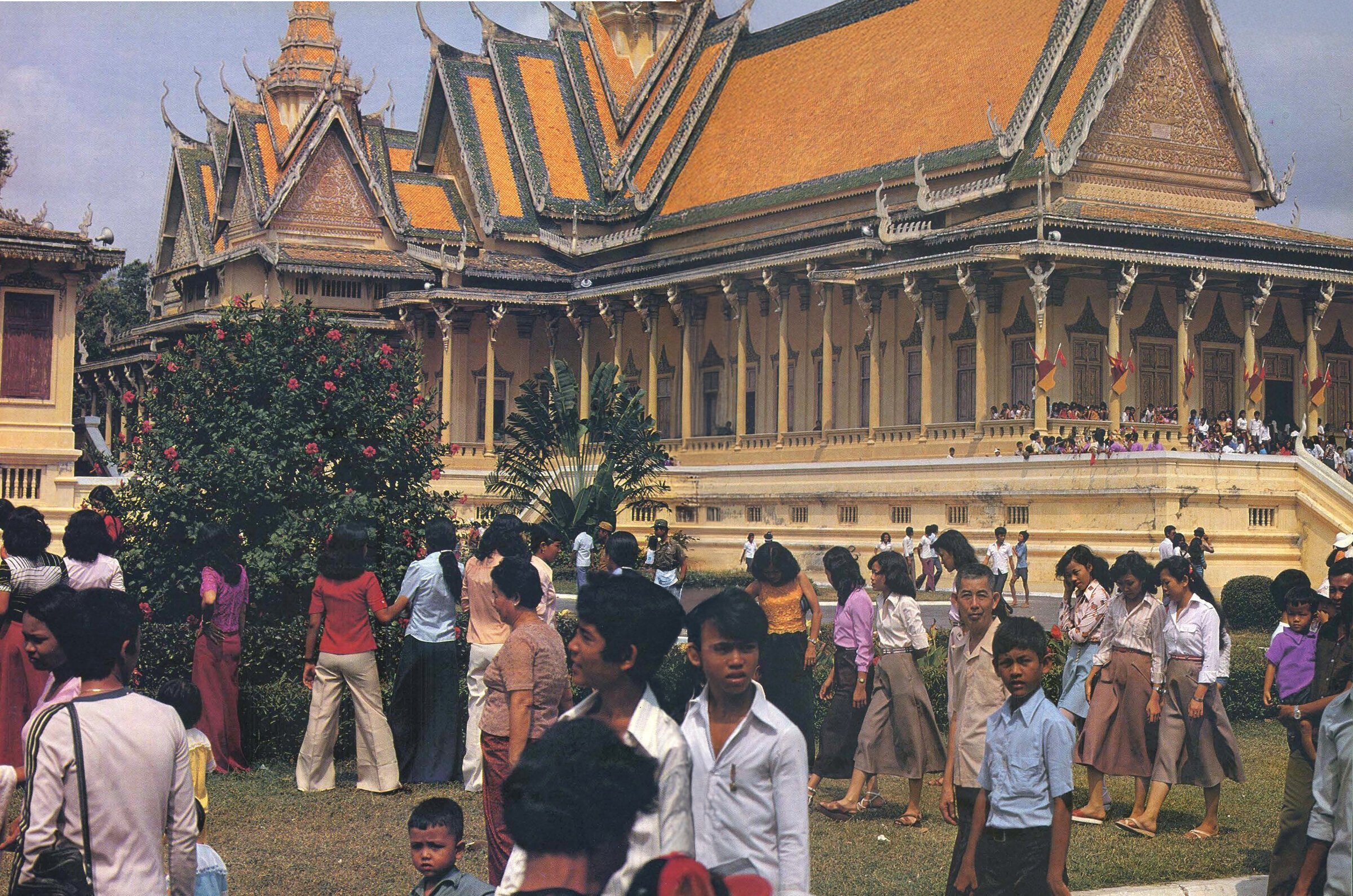

A rare and powerful visual documentation of Cambodia in the aftermath of the civil war.

- Formats

- e-book, on-demand books, ADB Physical Library, hardback

- Publisher

- Moscow, Планета (Страны мира) [Planeta, coll. "Countries of the World"].

- Edition

- print and pdf versions kindly shared by Mikhail Fiveyskiy, Nov. 2025.

- Published

- 1986

- Author

- Evgeny V. Kobelev

- Pages

- 200

- Language

- Russian

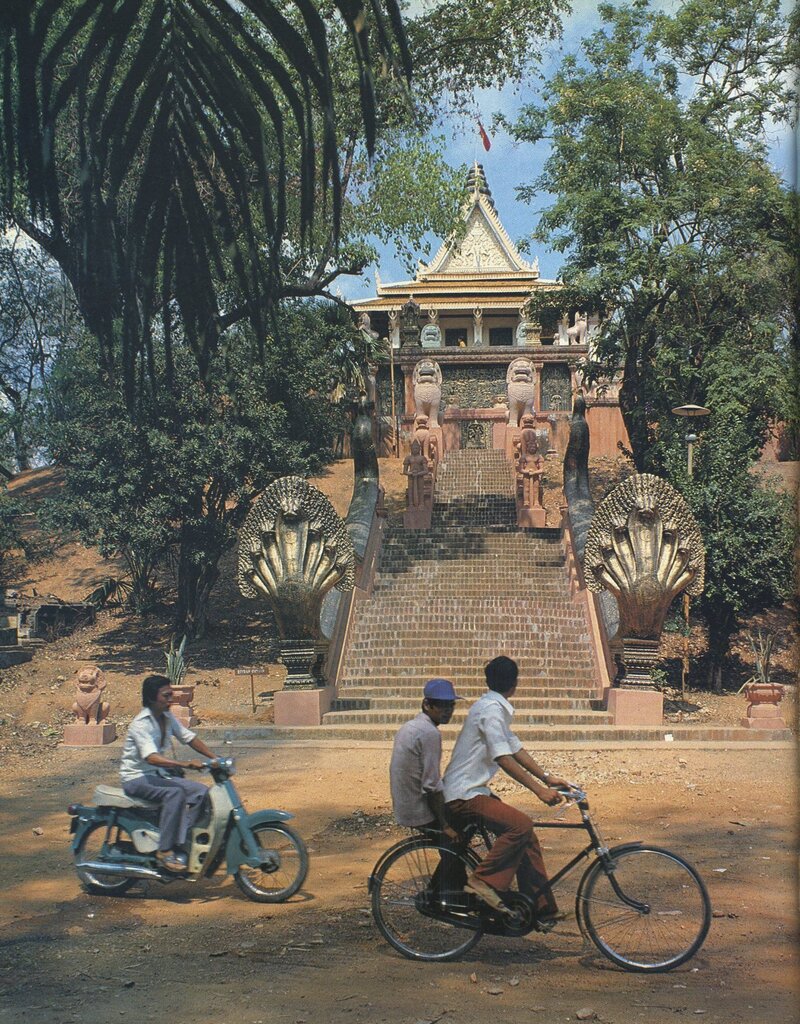

The early 1980s are mostly a black hole when it comes to photographic coverage of Cambodia. Apart from a handful of Western journalists, among them John Burgess for the Washington Post and Peter T. White (writer) with Wilbur E. Garrett and David A. Harvey (photos) for the National Geographic, as well as the works of Vietnamese and Cambodian photographers which remain largely unpublished, this photo album gives thus a valuable outlook on the people and the state of the country after the civil war.

To our knowledge, the earliest international report on Angkorian temples right after the war was published in 1980 by Jacques Danois [pseudonym of Jacques Maricq (11 Sept. 1927, Brussels – 20 Sept. 2008, Carpentras, France), a French reporter who had covered the Vietnam War and was then the UNICEF director of information. He was given a tour by Pich Keo, who had worked with Bernard-Philippe Groslier before the war and had just been appointed Director of Information, Press and Culture, and Curator of Angkor monuments. Pich Keo remarked that

There are no longer any documents on Angkor in Kampuchea. […]The only thing we are doing now is to clean up the place. But we have to be careful. In removing the over-growth, you risk breaking or damaging the bas-reliefs or the already fossilised stones. […] The Kampuchean people reassemble here. […] We are now at the gallery of a thousand Buddhas. Only 10 remain. The former régime removed 990. Some were broken in hate for Buddhism. Others were soid, mainly to neigh-bouring countries. [Jacques Danois, “Smiling ruins of Angkor Wat”, The Strait Times, 24 March 1980, p 7]. [ADB note: the new curator was then unaware of the fact that many artworks and documents had been hidden, often buried in the ground, and would start to reappear in the following years.]

See our selection of photographs by A. V. Lieberman from the 1986 photo album (same photos in the Russian and Khmer versions.)

See our selection of photographs by A. V. Lieberman from the 1986 photo album (same photos in the Russian and Khmer versions.)

While we quote from the text in its Khmer version in a separate entry, we concentrate here on the Russian view on the situation in Cambodia as reflected in the present book. E.V. Kobelev, who had already covered the American War in Vietnam and written extensively on the Vietnamese National Liberation Front and its leader Ho Chi Minh, followed here the official “political line” of Soviet Union regarding Southeast Asia at a time USSR ruler Leonid Brezhnev (19 Dec. 1906 – 10 Nov. 1982) had hardened the anti-Western propaganda. It was also the period of heightened tension with China, and Chinese overt support of the Khmer Rouge was certainly seen by Russian officials as a way to discredit Beijing in the region.

Depite the obvious informative (and visual) quality of the photographic work, E.V. Kobelev in post-war Cambodia was certainly a “political tourist”, to use the term coined by Marie Aberdam for Soviet journalists-cum-Party-officials visiting foreign countries [“Visites guidées au Kampuchéa Démocratique (1975−1978)”, Relations internationales 162, Jul-Sept 2015: 139 – 156]. In her article, the researcher showed that, far from the conventional conception of a strict policy of “closed borders”, the Khmer Rouge régime had initially sought international contacts with Thailand but even with Vietnam, as shown by the 15 – 17 February visit to Pol Pot by Hoang Van Loi, the Vietnamese vice Foreign Minister. In late December 1977, there had been a visit by a delegation of the Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist) including his chairman, Edward Fowler. As the Khmer Rouge’s threat persisted in the early 1980s, it was thus important to show Soviet strong support to the People’s Republic of Kampuchea.

The author’s memoirs, published in 2022, shortly before his death, reveals that Pol Pot sought for the recognition of USSR in the 1960s, long before his arrival to power. The part regarding Cambodia during and after the civil war goes as follows:

В Камбодже пришедший в апреле 1975 года к власти режим Пол Пота — Иенг Сари с первых же дней стал проводить преступную политику геноцида в отношении собственного народа и внешнюю политику открытой ксенофобии. При этом главным врагом был объявлен соседний Вьетнам, который всегда оказывал помощь и поддержку народу Камбоджи в его национально=освободительной борьбе. Несмотря на многочисленные попытки Ханоя урегулировать путем переговоров спорные проблемы, враждебность со стороны полпотовской Камбоджи нарастала с каждым днем. В декабре 1977 года полпотовский режим объявил о разрыве дипломатических отношений с Социалистической Республикой Вьетнам. К середине 1978 года полпотовцы сосредоточили в пограничных с Вьетнамом районах 19 пехотных дивизий (из 23, которыми они располагали).

В этих условиях, используя законное право на самооборону, Вьетнамская народная армия (ВНА), действуя совместно с вооруженными силами недавно созданного Единого фронта национального спасения Кампучии (ЕФНСК), развернула широкомасштабные военные действия на камбоджийской территории. 10 января 1979 года преступный полпотовский режим пал и была провозглашена Народная Республика Кампучия (НРК). В результате этих неожиданных, стремительно развивавшихся событий в Камбодже график моей работы значительно уплотнился. Провозглашение НРК резко изменило содержание и характер моей работы. Руководство отдела вменило мне в обязанность вплотную заниматься проблемами новой Кампучии. С полпотовским режимом Советский Союз не поддерживал отношений, поэтому камбоджийские вопросы находились на периферии внимания нашего сектора. Теперь же пришлось заняться ими вплотную, в частности, первым делом готовить

текст приветствия ЦК КПСС в адрес ЦК Единого фронта национального спасения Кампучии, затем вместе с Отделом Юго=Восточной Азии МИД СССР готовить текст признания правительством СССР Народной Республики Кампучии и

начинать подыскивать здание для будущего посольства НРК.Когда я стал заниматься делами Кампучии, я неожиданно обнаружил в сейфе нашего сектора письмо за подписью Пол Пота (который в 1960 — х годах был руководителем НРПК) в адрес советского посла в Пномпене, где он предлагал провести встречу. Посол послал на эту встречу рядового сотрудника, и встреча не состоялась. Как потом шутили наши специалисты по Камбодже и в ЦК, и в Отделе Юго=Восточной Азии МИД СССР, понятно, почему обидевшийся Пол Пот, придя к власти в стране, начал проводить оголтелую антивьетнамскую и антисоветскую политику. Руководство КПСС придавало важное значение победе ЕФНСК в Кампучии: прежде всего, были восстановлены отношения дружбы и сотрудничества между народами двух стран, разорванные полпотовским режимом, а также традиционное единство трех стран Индокитая под эгидой социалистического Вьетнама. Во вторых, появилась еще одна фактически коммунистическая партия, к тому же дружественная СССР. А этому фактору КПСС всегда, начиная со времен Коминтерна, уделяла первостепенное внимание.

[In Cambodia, the Pol Pot-Ieng Sary régime, which came to power in April 1975, immediately began pursuing a criminal policy of genocide against its own people and a foreign policy of open xenophobia. Neighboring Vietnam, which had always provided aid and support to the Cambodian people in their national liberation struggle, was declared the main enemy. Despite Hanoi’s numerous attempts to resolve contentious issues through negotiations, hostility from Pol Pot’s Cambodia grew daily. In December 1977, the Pol Pot régime announced the severance of diplomatic relations with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. By mid-1978, Pol Pot’s forces had concentrated 19 infantry divisions (out of 23 at their disposal) in the areas bordering Vietnam.

Under these circumstances, exercising its legitimate right to self-defense, the Vietnam People’s Army (VPA), acting jointly with the armed forces of the newly formed United Front for the National Salvation of Kampuchea (UFNSK), launched large-scale military operations on Cambodian territory. On January 10, 1979, the criminal Pol Pot régime fell, and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) was proclaimed. As a result of these unexpected, rapidly unfolding events in Cambodia, my work schedule became significantly more intensive. The proclamation of the PRK dramatically changed the content and nature of my work. Department leadership tasked me with closely addressing the problems of the new Kampuchea. The Soviet Union did not maintain relations with the Pol Pot régime, so Cambodian issues remained on the periphery of our sector’s attention. Now I had to tackle them head-on, specifically, first preparing the text of the Central Committee’s greetings to the Central Committee of the United Front for the National Salvation of Kampuchea, then, together with the Southeast Asia Department of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs, preparing the text of the USSR government’s recognition of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea and beginning to search for a building for the future PRK embassy.

When I began working on Kampuchea affairs, I unexpectedly discovered in our sector’s safe a letter signed by Pol Pot (who had led the NPRK in the 1960s) addressed to the Soviet ambassador in Phnom Penh, proposing a meeting. As the ambassador sent a rank-and-file employee, the meeting never took place. As our Cambodia specialists in both the Central Committee and the Southeast Asia Department of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs later joked, it’s understandable why the offended Pol Pot, upon coming to power, began pursuing a rabid anti-Vietnamese and anti-Soviet policy. The CPSU leadership attached great importance to the victory of the EFNSK in Kampuchea: first of all, it restored the friendly and cooperative relations between the peoples of the two countries, severed by the Pol Pot régime, as well as the traditional unity of the three Indochinese countries under the auspices of socialist Vietnam. Secondly, it gave birth to another de facto communist party, one friendly to the USSR. And the CPSU, beginning with the days of the Comintern, had always prioritized this factor.][65 Years with Vietnam, 2022, p 97 – 8]

Around the 1989 Vietnamese withdrawal

1) An uncredited photograph taken inside Angkor Wat and illustrating one of the earliest eye-witness reports, published in The Strait Times on 24 March 1980. 2) Withdrawal of the last 24, 000 Vietnamese soldiers — out of the 100, 000 who entered Cambodia from April to December 1978 — in September 1989. This rare photograph has been often reproduced in the Vietnamese media with the caption: “Soldiers-Volunteers leave Cambodia, sparking everlasting nostalgia among residents of the neighboring countries.” [photo by Chip Hires/Gamma-Rapho, courtesy of the author.]

1) An uncredited photograph taken inside Angkor Wat and illustrating one of the earliest eye-witness reports, published in The Strait Times on 24 March 1980. 2) Withdrawal of the last 24, 000 Vietnamese soldiers — out of the 100, 000 who entered Cambodia from April to December 1978 — in September 1989. This rare photograph has been often reproduced in the Vietnamese media with the caption: “Soldiers-Volunteers leave Cambodia, sparking everlasting nostalgia among residents of the neighboring countries.” [photo by Chip Hires/Gamma-Rapho, courtesy of the author.]

1) An uncredited photograph taken inside Angkor Wat and illustrating one of the earliest eye-witness reports, published in The Strait Times on 24 March 1980. 2) Withdrawal of the last 24, 000 Vietnamese soldiers — out of the 100, 000 who entered Cambodia from April to December 1978 — in September 1989. This rare photograph has been often reproduced in the Vietnamese media with the caption: “Soldiers-Volunteers leave Cambodia, sparking everlasting nostalgia among residents of the neighboring countries.” [photo by Chip Hires/Gamma-Rapho, courtesy of the author.]

In the Khmer version of the photo album, we read

The Party and Government of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea are paying attention to the task of strengthening the Kampuchean Revolutionary People’s Army. The Kampuchean Revolutionary People’s Army, together with the Vietnamese Volunteer Army, which is in the country in accordance with the Agreement on Peace, Friendship and Mutual Assistance between the People’s Republic of Kampuchea and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, is conducting a large-scale campaign to crush the Pol Pot renegades and their strongholds. The steady strengthening of security and stability in Cambodia allows for the gradual withdrawal of units of the Vietnamese Volunteer Army each year. The Government and people of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea highly appreciate the internationalist mission of the Vietnamese Volunteer Army in Cambodia. [The two countries] have announced that the Vietnamese troops present in Cambodia at the request of the legitimate government of this country will be completely withdrawn from Cambodia by the beginning of 1989 [ADB: a first important withdrawal had been effective in May 1983].

The Vietnamese intervention had encountered a widespread backlash from the international community — except for USSR -, and Japan had suspended its economic aid to a country left worn out by the French and American wars. But how did the Cambodian public really feel about the involvement of a neighbor generally feared for a long history of encroachment and aggression? Reflected through books and movies on the Vietnamese side, the intervention hasn’t found any significative echo in Cambodian culture. Today, for instance, not many in Cambodia remember that the sinister S‑21 camp, location of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, was first discovered and reported in 1979 by a Vietnamese war reporter, Hồ Văn Tây.

Margaret Slocomb, who researched the National Archive of Cambodia to better understand the roots of the Khmer Rouge régime, and Michael Vickery were among the few independent researchers who attempted to dive into the intricacies of a situation marked by the scars of the Vietnam War and the relentless Cold-War rethorics. The latter, in his Cambodia 1975 – 1982 (published in 1984, at the time the photographer and author of this photo album were busy gathering material in Cambodia), recorded in the early 1980s the testimony of Cambodian refugees and survivors in the country, concluding that the Vietnamese intervention was not perceived as the “invasion” depicted in the mainstream media in the West. This work was a response to the ‘Standard Total View’ (STV) which designated the Vietnamese, and even the PRK, as persecutors of the Cambodian people The STV for 1979 – 81, asserting that “the Vietnamese wished to destroy the surviving Khmer intellectuals, and if they had not yet started killing them, they soon would. It was alleged that Khmer intellectuals and administrators were sent for study and training to Vietnam, from which they never returned, that others simply disappear, or are arrested and imprisoned for undisclosed reasons. The Vietnamese were further accused of destroying Cambodia by taking away the rice which was available in early 1979, misappropriating rice seed, preventing people from harvesting, holding up distribution of foreign aid, and attempting to massacre those who came to the Thai border to receive such

aid [p 37]. Against these assertions, Vickery noted:

- A reluctance to move back to the city from some people earlier displaced by the Khmer Rouge, whose “choice, in contrast to the conventional wisdom about the relative desirability of different situations in 1979, was to remain peasants, alleging that they could feed themselves and their families better than working in Phnom Penh as government employees.” [p 227]

- “Even the most respectable of the Khmer Serei, Son Sann’s KPNLF, could not resist claiming that the Vietnamese had stolen all the gold from the National Bank (ignoring that the bank had first been plundered by departing Lon Nol officials and then dynamited during DK times) and all the treasures in various temples of Phnom Penh (interesting to juxtapose with earlier claims about DK violence to temples), and that they had imposed their dong on Cambodia in order to buy up cheaply all the valuable goods still in private hands. Their comment on the new field, just being introduced, was that it was a Hanoi device to buy up Khmer rice with worthless paper. […] We now know that there was probably never a Vietnamese plan to impose the dong throughout Indochina, and that in early 1980 a new fiel displaced it in Cambodia [p 209].

- “The early reports about Vietnamization of the syllabus and the forced instruction of Vietnamese language in schools proved to be untrue. Not only the Nong Chan peasants denied that it was so in village schools, but a relatively important Education Ministry employee who defected in June 1980, and whose views on the PRK were very negative, said that Vietnamese Ianguage instruction had been proposed, but rejected by the Khmer education committees (in spite of the alleged Vietnamese oppression) and the idea indefinitely shelved.” [p 233]

- While rejection most of the argumentation of Stephen R. ‘Steve’ Heder, a political historian specializing in the history Khmer Rouge régime, Vickery opined that the latter was “entirely correct, nevertheless, in remarks to the effect that a large Vietnamese presence may exacerbate any other contradictions that arise. Foreign armies always do, particularly when partisan regimes have for several generations inculcated a ‘hereditary enemy’ mentality in their people, a practice characteristic of the Sihanouk and Lon Nol periods. This is true even when, as in Cambodia, the Vietnamese perform tasks which are of clear public utility — guarding roads and bridges, removing mines laid by the DK and KPNLF, and defending the northwest border against those organizations. And a foreign presence is irritating even when, as in Cambodia, their style of life is as modest as that or he local population and their behavior exemplary. Although Heder is right to be concerned about the long-term effects of such a large Vietnamese garrison, his advocacy of increasing American military support for the enemies of the PRK can only serve to increase and prolong the Vietnamese presence and exacerbate further the contradictions which he claims to see in PRK Cambodia.” [p 249 – 50]

The following political developments confirmed these predicitions: in early May 1989, the PRK restored the name “Cambodia” by renaming the country State of Cambodia (SOC) and started its transition toward the abandonment of Marxist – Leninist ideology and the recognition that the restoration of the Kingdom of Cambodia in 1993 was the best political solution. In 1992 – 1993, the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), formed following the 1991 Paris Peace Accords, carried its administrative and peacekeeping operation, a first for the UN to assume direct responsibility for the administration of an outright independent state.

With hindsight, the years covered in this photo album and the subsequent withdrawal of the Vietnamese forces can be seen through different prisms. Western conservative pundits saw it as the last (and failed) attempt to drag Cambodia into a Marxist-Leninist adventure. Or, as Russian analyst Nadjeda Bektimyrova posited in 2010,

The West understood perfectly well that the presence of the Vietnamese army saved the Cambodians from the vengeance of the Khmer Rouge. However, within the bipolar system, superpower interests had absolute priority, and the PRK belonged to the strategic enemy camp. [Надежда Бектимирова, “Общий путь к урегулированию в Камбодже” [“A Common Path to Peace in Cambodia”, РОССИЯ — АСЕАН [Russia-Asean Review] 10, 2010: 96 – 105.]

Credits

Фотоальбом | Авторы текста и составители : ЕВГЕНИЙ ВАСИЛЬЕВИЧ КОБЕЛЕВ, НИКОЛАЙ НИКОЛАЕВИЧ СОЛНЦЕВ

Специальная съемка: АЛЬБЕРТА ВИКТОРОВИЧА ЛИБЕРМАНА | Художник: БОРИС КЛАВДИЕВИЧ УШАЦКИЙ | Под общей редакцией ИВАНА ИВАНОВИЧА КОВАЛЕНКО | В альбоме использованы фотографии В. Будана | Заведующий Главной редакцией общественно·nолитических, оперативных и спе циальных фотоизданий: А. Е. Порожняков | Редактор: Э. И. Аристова | Художественные редакторы: Н. А. Ушацкая , Н. И . Рудакова | Технический редактор: Т. А. Хле6нова | Корректоры: Н. И. Коршунова, 3. М. Петрова.

[Photo Album | Authors and compilers: EVGENY VASILEVICH KOBELEV, NIKOLAY NIKOLAEVICH SOLNTSEV

Special photography: ALBERT VIKTOROVICH LIEBERMAN | Artist: BORIS KLAVDIEVICH USHATSKY | General editor: IVAN IVANOVICH KOVALENKO | The album uses photographs by V. Budan | Head of the Editorial Board of Socio-Political, Operational, and Special Photo Publications: A. E. Porozhnyakov | Editor: E. I. Aristova | Art editors: N. A. Ushatskaya, N. I. Rudakova | Technical editor: T. A. Khlenova | Proofreaders: N. I. Korshunova, Z. M. Petrova.]

About co-author Nikolai Nikolaevich Solntsev Николай Николаевич Солнцев: N.N. Sonltsev (1933−1990) was a Russian TV and radio journalist covering Indochina and China from the early 1960s, a co-chairman of the Soviet-Kampuchean Friendship Society and a member of the Bureau of the Soviet Committee for Support of the Peoples of Vietnam, Laos, and Kampuchea. After studying at Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies, he worked at the USSR State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company in the section broadcasting programs destined to Southeast Asian countries. He covered on the field guerilla activities in Laos, North and South Vietnam as well as liberated zones in Cambodia at the end of the 1970s. Author of some 15 films about Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and China, he contributed to several books and authored Китай: стены и люди [China: Walls and People] (1981).

About this book on Angkor Database

We found one badly damaged copy of the Khmer version of this important photo album in the personal papers of the late Cambodian architect Dy Proeung at his house in Siem Reap. By working on the Khmer text, written by Cambodian scholar Long Seam when he was working in Moscow, we gathered that the book was initially published there around 1987. We showed that copy to several Cambodian historians and history lovers, who confirmed the historical value of the publication, which we scanned for safety. We started to look for the Russian edition and mentioned it to photographer Chip Hires, who had covered the withdrawal of the Vietnamese forces from liberated Cambodia in September 1989. Chip put us in touch with researcher Mikhail Fiveyskiy from the photo agency East News Russia, Moscow, who was kind enough to find the pdf version of the book. Our warmest thanks to them. - B.C.

Tags: civil war, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, United Salvation Front, Vietnam, Vietnam War, Russia, Russian researchers, USSR

Associated Items

About the Author

Evgeny V. Kobelev

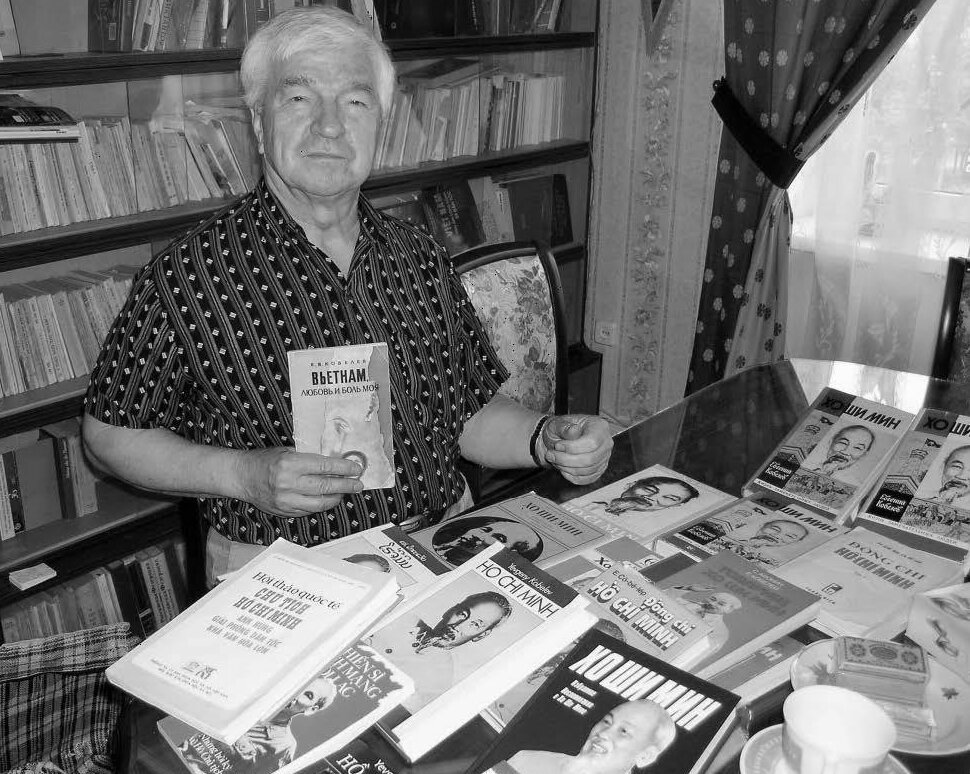

Evgeny Vasilyevich Kobelev Евгений Васильевич Кобелев [E.V. Kobelev (Е.В. Кобелев)] (2 May 1938, Ulyanovsk — 5 May 2025, Moscow, Russia) was a Russian reporter and researcher who covered the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1975 and co-authored the one and only illustrated book on Cambodia immediately after the civil war, Kампучия восставшая из пепла [Cambodia Risen From the Ashes], edited in Khmer as ការស្ថាបនាប្រទេសកម្ពុជាក្រោយគ្រោះមហន្តរាយ [Cambodia: Rebuilding After the Disaster], published in Moscow and Phnom Penh in 1986.

While studying at Lomonosov Moscow State University , E.V. Kobelev was one of the first Soviet students to opt for studying Vietnamese language and civilization. As reflected in the title of his first published book, Вьетнам, любовь и боль моя [Vietnam, My Love and My Pain] (1969), Vietnam, the Vietnam (or “American”) War and the neighboring countries of Cambodia and Laos determined both his fate and his entire career.

As a correspondent with the state news agency TASS, he covered the conflict on the field starting from 1964, pursuing his academic research on modern Vietnamese history and publishing in 1979 the first exhaustive biography of revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh in Russian, with numerous translations abroad. As a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Soviet Union (CPSU) until 1991, he supervised relations with the communist parties and revolutionary movements of the Indochina countries.

Active in several international committees devoted to public diplomacy (Russian-Vietnamese Friendship Society, Solidarity Committee with the People of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia), E. V. Kobelev joined the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, in 1991. He furthered his study on Southeast Asia, in particular the “реакционная клика Пол Пота” [Pol Pot’s reactionary clique], concentrating on Vietnamese contemporary politics. In 2008, he established and led until 2013 the Центр изучения Вьетнама и АСЕАН (Center for Vietnam and ASEAN Studies) at the Institute of Far Eastern Studies [IFES, now Institute of China and Modern Asia (ICCA)].

1) As a TASS correspondent in Vietnam, 1965. 2) With several of his published books. 3) With daughter Tania in Leningrad, 1989. [all photos from E.V. Kobelev, 65 Years with Vietnam: Memories, 2022.] 4) Cover of his 1986 book on Cambodia, with photographs by A.V. Lieberman.

1) As a TASS correspondent in Vietnam, 1965. 2) With several of his published books. 3) With daughter Tania in Leningrad, 1989. [all photos from E.V. Kobelev, 65 Years with Vietnam: Memories, 2022.] 4) Cover of his 1986 book on Cambodia, with photographs by A.V. Lieberman.

1) As a TASS correspondent in Vietnam, 1965. 2) With several of his published books. 3) With daughter Tania in Leningrad, 1989. [all photos from E.V. Kobelev, 65 Years with Vietnam: Memories, 2022.] 4) Cover of his 1986 book on Cambodia, with photographs by A.V. Lieberman.

Publications

- Вьетнам, любовь и боль моя [Vietnam, My Love and My Pain], 1969.

- Торжество правого дела народов Индокитая [The Triumph of the Just Cause of the Peoples of Indochina], 1975.

- [editor] Хо Ши Мин. Избранное (Библиотека вьетнамской литературы) [Ho Chi Minh: Selected Works (Library of Vietnamese Literature)], Moscow, [Progress], 1979, 295 p.

- [editor] Кампучия: От трагедии к возрождению [Cambodia, From Tragedy to Rebirth], Moscow, Политиздат [Politizdat], 1979, 255 p.

- [with Сергей Афонин [Serguei Afonin]] Товарищ Хо Ши Мин [Comrade Ho Chi Minh], 1980.

- Хо Ши Мин [Ho Chi Minh], Moscow, Молодая гвардия — Жизнь замечательных людей [Youth Guard, series ‘Life of Remarkable People’], 1983.

- [теле-фильм [TV film], with Н. Н. Солнцев [N.N. Solntsev]] Хо Ши Мин: память об источнике [Ho Chi Minh, Memory from the source], 1984.

- [ed.] Кампучия: жизнь после смерти [Kampuchea, Life After Death], Moscow, Политиздат [Politizdat],1985, 223 p.

- [with Н. Н. Солнцев [N.N. Solntsev], photos by А.В. Либерман [A.V. Lieberman]] Kампучия восставшая из пепла [Cambodia Risen From the Ashes], photo album, Moscow, Планета [Planeta], 200 p, 1986. [KH edition: ការស្ថាបនាប្រទេសកម្ពុជាក្រោយគ្រោះមហន្តរាយ [Cambodia: Rebuilding After the Disaster], tr. by Long Seam, Planeta,1988.

- [with Г.М. Локшин G.M. Loshkin, Н.П. Малетин N.P. Maletyn] АСЕАН в начале XXI века: Актуальные проблемы и перспективы [ASEAN at the Start of 21st Century: Problems and Perspectives], Moscow, ФОРУМ [Forum Publ.], 2010, 367 p.

- [with А.С. Воронин [A.S. Boronin] СССР/Россия-Вьетнам: Вехи сотрудничества [USSR/Russia-Vietnam: Milestones of Cooperation], 2011, 224 p. ISBN 978−5−985−47−062−8.

- “Бао Дaй, последний император Вьетнама” [“Bao Day, Last Emperor of Vietnam”, Russian Journal of Vietnamese Studies (RJVS) [ISSN 2618 – 9453 (Online)], Vol 1, No 2 (2012): 251 – 295.

- “Памяти друга” [“Remembering A Friend”] : RJVS, Vol 1, No 3 (2013): 365 – 372.

- [ed. with V. Mazyrin] Russian Scholars on Vietnam. Selected Papers, Moscow, Forum Publ., 2014, 251 p.

- 65 лет вместе с Вьетнамом. Воспоминания [65 Years with Vietnam: Memories], Moscow, ИКСА РАН [ICCA-Russian Academy of Sciences], 2022, 200 p. ISBN 9785838104373.

- “Хо Ши Мин и Россия (К 100-летию первого прибытия Хо Ши Мина в нашу страну 30 июня 1923 года)” [“Ho Chi Minh and Russia (On the 100th anniversary of Ho Chi Minh’s first arrival to our country on June 30, 1923)”], Восточная Азия: факты и аналитика [East Asia: Facts and Analytics] n 3, 2023: 69 – 80.

- [ed. by Е.В. Никулина Elena Nikulina] Пульс времени : Избранные статьи. К 85-летию ученого [The Pulse of Time, Selected articles on the scholar’s 85th birthday], Moscow, ИКСА РАН [ICCA RAS], 2023, 381 p. ISBN 9785838104670.