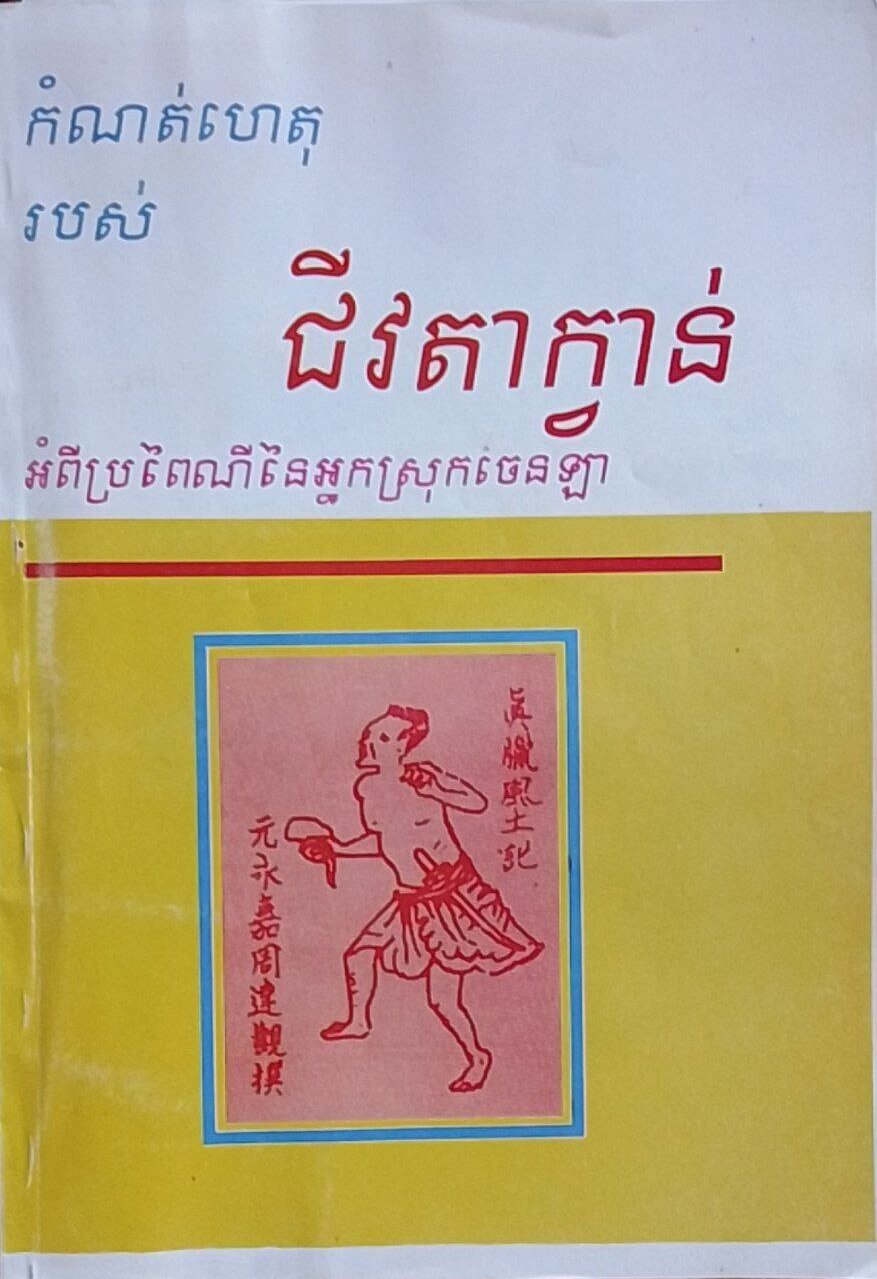

កំណត់ហេតុរបស់លោក ជីវ តាក្វាន់ អំពីប្រពៃណីនៃអ្នកស្រុកចេនឡា [Chiv Ta-Kwan's Diary] | Zhou Daguan's Diary on Traditions of the People of Chenla

by Zhou Daguan & Theam Teng Ly

The first Khmer translation of Zhou Daguan's 'Customs of Chenla', now fully available online.

Type: e-book

Publisher: Morha Leap Printing House រោងពុម្ព មហាលាភ, Phnom Penh, 2516 saka, 1973, 3d edition.

Edition: ADB digital version prepared by Ranith Soboros, 2024.

Published: 1973

Pages: 76

Languages : Khmer, Chinese

ADB Library Catalog ID: eZHOUTTLY

In order to help the research on the unique written source regarding Angkor in the 13th century, we are publishing here the digital version of Ly Team Teng’s work, initially published in 1973.

While the author was not completely familiar with ancient Chinese, as he acknowledged in his introduction (see Translator’s Comments below), his contribution in clarifying some 41 Khmer words Zhou Daguan adapted to the Chinese language — as identified by Paul Pelliot and not including location names — has been lauded by researcher Uk Solang, himself author of an English translation. Uk Solang had discovered a copy of Ly Team Teng’s book in a Phnom Penh bookstore in 2004, while he was researching for his translation (along with wife Solang), and had contacted Ly Team Teng’s widow and son.

There are many comments forthcoming about the translator’s choice. We’ll point out just one example, the last sentence on Chapter 6, where LTT translate the Chinese 二形人 Er xing ren , literally “people with two forms”, by “មនុស្សស្រីភេទខ្លះស្អាតៗ”, “some beautiful women”. Remark that Uk Solang, in his English translation, used the translation “transvestites”, which is not satisfying. Paul Pelliot wrote “mignons”, French equivalent of Peter Harris’ “effeminate men”, pointing to the “transgender” aspect of these individuals. They certainly were what is still largely known in South East Asia as ‘katoey” people.

Translator’s Comments

“The diary of Zhou Daguan [Chiv Takwan in Khmer transliteration] about the traditions of the Chenla people” the reader is now holding is really a sacred document of our Khmer history. In every history book or any study on Cambodia, reference to Zhou Daguan’s document was never omitted. The Cambodian youth who learns the history of their own country, will surely know the name: Chiv Ta Kwan, but what we do know are just consecutive words that was told from one to another, book copied after one another, from one book to another through the translation from the original book In French language by Paul Pelliot who translate from the Chinese article and was first published in the Bulletin of the French School of the Far East (Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extreme-Orient, BEFEO) in 1902. After Pelliot’s death, George Cœdès took his work, including additional commentary, to publish it as a book in 1951. Pelliot stated in his preface that he once had tried to translate from a document of Chiv Ta Kwan that Abel Rémusat has translate and had lunched the first publication in 1819 but not yet a perfection. George Cœdès, himself has been living in China for years until he can complete this work.

We, Khmer people would like to thank you especially for these researchers as their work is same as helping us to discover such a precious treasure. Because of those translators/researchers aren’t Cambodian, we always thought that if any Cambodian can translate directly from the Chinese texts, we would feel more satisfied even though it is not a perfect translation.

I used to learn Chinese character for four years since I was young but had forgotten almost everything, only recalling some characters that I often used and can copy the Chinese texts. After seeing the translation of Pelliot including some Chinese texts along with explanations such as the name of the district and references of publications, I just kept noting down those detail as a document.

Fortunately, in 1962, I was given a cultural mission to lead a delegation of Cambodian writers to China. I always had a thought to ask for the document of Chiv Ta Kwan as I will be able to come to China, his home country. When I met with the Chinese minister of Culture, who was also the president of the Chinese Writers Association, I requested him to see Chiv Ta Kwan’s writing with my desire to see and copy this document. The Minister of Culture agreed to fulfill my wish. That night, I was so excited and hoped for morning to arrive so I could go to visit their national library. I didn’t get to go to the National Library the next morning, as we had a program to visit places far away from town first. It was not until five days later that I was taken to the “rare book section” in the National Library in Beijing. The librarian together with the other two collaborators — a librarian from the Rare Books section and Tea Siv Meng, 69, a specialist in researching the history of the Far East Countries, were waiting for me. Tea Siv Meng was the one who prepared a pile of books to show me, which are all related to the history of Cambodia and were all published from the 14th to the 17th centuries. We had a long conversation as he wanted to see if I really know and interested in the history or just asking in a way to show off. Fortunately, I have seen a lot of documents on the relationship between the two countries, and before coming to China, I also recorded these documents, because my mission is on this cultural issue. I answer to him in an agile response until the other party took me to meet the head of the history department.

Among those thick books, some only describe about our country in only a few pages. An only one book called “The History of the Mongolian Empire” which has a large part that was briefly describing about sending a missionary, Chiv Ta Kwan to Chenla. I asked to copy this whole book, 63 pages, and they agreed to let me copy, resulting in a big file of pictures. After arriving back in Cambodia, I printed out the photos but unfortunately, they weren’t clear enough to understand the letters on it. I gathered all of the printed photos, compiled them as a book, and kept it at the Khmer Writers Association, hoping that in the future, someone may be able to translate it. Two years later, the book was lost and no one knew where it was or who took it. I assumed that the person who took the book must had deliberately taken it to keep as their own, or to hid it to prevent anybody from translating the article. Luckily, I still had another file of the photos I took back then in China and printed out, translated and published. Even though, it was not perfect but it helps to contribute to the work of Cambodian researchers. Secondly, it also adds to the number of useful information.

This translation work had me worried as I have to find someone who can translate Chinese texts and ancient Chinese texts. However, we couldn’t find anyone with sufficient knowledge to do so. Most of the translators only have sufficient knowledge to translate modern Chinese texts, but not ancient Chinese texts. One of my friends, Eung Lay was a writer in 1955 – 1956, then a translator and subtitler for Chinese films, was able to translate old Chinese texts. He promised to gives his full support and we did translate the whole book. When there are difficult words, he checks the dictionary and write a note with the definition for me. My other friend, Ma Eang used to be a Khmer literature teacher at a Chinese school also have helped me to translate some part of the book. I put together the two translated works and compared the original text to the one we have translated, and also to Pelliot’s French translation. This was still unsatisfied for me. One day, I ran into my former teacher, Tang Suy Kong, who’s now 71 years of age. When I was learning Chinese in 1940, he was a professor of Khmer literature. He knew many stories and was self-taught, following traditional Chinese methods. Currently, he lives with his children and grandchildren, some of whom work as civil servants while others are involved in business. I asked him to help me verifying the meaning. He was happy to help with the translation. He then explained me chapter by chapter, with me attempting to verify the meaning of my translation, adding any missing part, amending wrong spelling, adding clarification notes to the most difficult to understand parts, always following what he told me. After three months, we finalized the piece nd published it.

On the other hand, there are different tones in the Chinese language, depending on the dialects, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Cantonese, Teochew, and Hokkien. Chiv Ta Kwan was born in Wenzhou, southeast of China. Therefore, his language is very special, just like his hometown. In Chenla, there are no Chinese from Wenzhou, only those from Kwang Tung, known as Cantonese or Teochew, who have settled and been living in Chenla. That is why the accent of the words he tried to replicate from Khmer was very difficult to understand, partly due to the Cantonese or Teochew accents of the Chinese translators who assisted him. In this translation, we agreed to follow the Teochew accent as the primary one because the Teochew community had the largest population living in Chenla and most of Chinese speakers would pronounce the the Khmer words translated from Chinese according to the Teochew accent.

Therefore, I would like to apologize in advance to those of you who have a deep understanding of Chinese if my team and I have made any omissions, or if there are any gaps in our transcription.

Phnom Penh. June, 1971 — LY Theam Teng (translated by Ranith Soboros).

Tags: Zhou Daguan , Chinese sources, translations, Khmer translations, linguistics

About the Author

Zhou Daguan

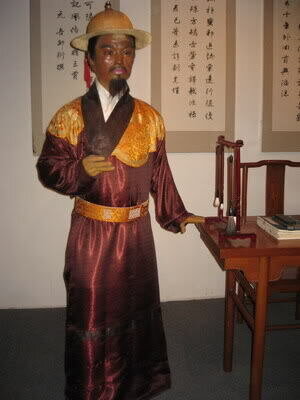

Zhou Daguan (also Tcheou Ta-Kouan, Zhu Daguan) ch 周达观 , kh ជីវតាក្វាន់ (chiv takvan), vn Chu Đạt Quan, th โจวต้ากวาน (cho wta kwan)(c. 1270, Yongjia (modern Wenzhou) – ? shortly after 1346), a Chinese traveler under the Temür Khan (Emperor Chengzong), authored the sole written and direct account of the customs of Cambodia and the Angkorean power from the 13th century that has been preserved to our days.

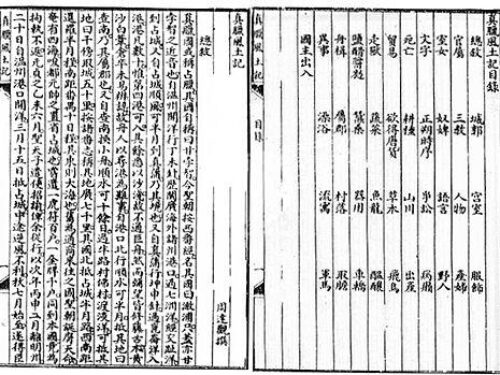

Arrived at Angkor in August 1295, he remained near the court of King Indravarman III (also named Sri Srindarvarman) until July 1296. We know only a third of his account, The Customs of Cambodia (真臘風土記, Zhēnlà Fēngtǔ Jì, literally The Land and Social Conditions of Chenla), first translated into French by the sinologist Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat in 1819 (Description du royaume de Cambodge par un voyageur chinois qui a visité cette contrée à la fin du XIII siècle, précédée d’une notice chronologique sur ce même pays, extraite des Annales de la Chine, Imprimerie J. Smith, 1819), and later on by Paul Pelliot in 1902 (1). In 2007, the linguist Peter Harris completed the first direct translation from Chinese to modern English.

Coincidentally, Zhou Daguan’s travel to Angkor occurred the same year than “the trader and adventurer Marco Polo arrived back in Venice after twenty-five years’ absence. Legend has it that he was full of stories about his travels in China and other parts of Asia, and about the services he provided to the great khan Khubilai, the founding emperor of the Mongol dynasty then ruling China. That same year, 1295, a young man by the name of Zhou Daguan set sail from Mingzhou, a port on the southeast coast of China. Zhou was headed for Cambodia as part of a delegation sent there by Khubilai’s grandson Temür, who had come to the imperial throne on the death of his grandfather.” (cf. Peter Harris, A Record of Cambodia, p 6).

We still have to conjecture in which capacity Zhou Daguan joined the delegation, but we know he was not a diplomat acting for the Yuan dynasty, nor a trader. The “Summary of the General Catalogue of the Complete Library of the Four Treasures” of the Qing Dynasty, praising the book as “quite comprehensive and rich in meaning, with many details, which can make up for the missing parts of the Yuan History,” mentions its author as a “lettered man.”

As for the name Daguan 达观, which he used after his trip to Chenla, several interpretations have been given: “the one who saw everything”, “at ease in every circumstance”, “who sees the bright side of everything”.

Sinologist and Khmerologist Pascal Médeville is currently working on a novelized account of Zhou Daguan’s life and travels. And in December 2024, Princess Buppha Devi Dance School presented in Phnom Penh the first musical and dance production inspired by the journey of Zhou Daguan, លោក ជីវ តាក្វាន់ បានជួបនគរចេនឡា Zhou Daguan in the Kingdom of Chenla.

Angkor Database recommends the direct translation established from the ancient Chinese text into English by native Chinese Ms. Beling Uk and native Cambodian Solang Uk in 2010 and 2011. Xia Nai’s 1981 Chinese edition of the travelogue remains a reference.

Customs of Zhenla has also been translated into:

- Khmer: កំណត់ហេតុរបស់លោក ជីវ តាក្វាន់ អំពីប្រពៃណីនៃអ្នកស្រុកចេនឡា [Chiv Ta Kwan [Zhou Daguan]‘s diary about the traditions of the people of Chenla], tr. Ly Team Teng, 1971, Phnom Penh.

- Thai: โจวต้ากวาน, บันทึกว่าด้วยขนบธรรมเนียมประเพณีของเจินละ เฉลิม ยงบุญ [Record of Chenla’s customs and traditions], tr. Chalerm Yongbunkerd, 2014 (3d edition) — ISBN 978−974−02−1326−0.

- Vietnamese: Chu Đạt Quan, Chân Lạp phong thổ ký [Chenla Land and People], tr. Lê Hương, Nhà xuất bản Kỷ Nguyên Mới, Saigon, 1973 [excerpts in Vietnamese here].

- German: Walter Aschmoneit, Zhou Daguan, Aufzeichnungen über die Gebräuche Kambodschas, Studeingemienschaft Kambodschanische Kultur, 2006, 120 p., ISBN13 978 – 3000200724.

- Spanish: Vida y costumbres de Camboya, Relato del viaje de Zhou Daguan a Angkor, by Astrid Haardt, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013, 108 p., ISBN13 978 – 1478384496.

(1) In Antoine Brébion’s Dictionnaire Bibliographique, the entry Tcheou-Ta-Kouan states: ‘Lettré chinois du XIIIe siècle de notre ère, qui avait pour appellation Ts’ao-T’ING; il était originaire de Yong-Kia au Tchô-Kiang, il suivit l’ambassade chinoise envoyée au Cambodge en 1295, il revint en Chine en 1297. Le très érudit sinologue qu’est M. P. PELLIOT, de l’Ecole française d’Extreme-Orient, lui a restitué la paternité d’une relation intitulée Description du Cambodge, qu’ABEL DE RÉMUSAT avait attribuée à MA-TOUAN-LIN.’ [Chinese erudite from the 13th century CE, who was named Tsao-Ting, hailing from Yong-Kia in Tcho-Kiang. He followed the Chinese embassy sent to Cambodia in 1295, traveling back to China in 1297. The most learned sinologist Mr P. PELLIOT, from EFEO, has given back to him the autorship of a text titled ‘Description of Cambodia’, previously attributed to MA-TOUAN-LIN by ABEL DE RÉMUSAT.]

About the Translator

Theam Teng Ly

Ly Theam Teng លីធាមតេង 李添丁 [also Li Dham Ten] (15 May 1930, Kompong Siem District — 1978, captive of the Khmer Rouge) was a Sino-Khmer researcher and author who wrote many essays and novels that became Cambodian literature classics, and authored the first Khmer translation of Zhou Daguan’s 13th century account Zhenla and Its People, a work he considered as “sacred”, since it is the only written relation of Angkor during the Khmer relation.

As a young reaseacher at Phnom Penh Buddhist Institute, he was remarked by ethnologist Éveline Porée-Maspéro, who appointed him at the Commission for the Study of the Cambodian Mores and Customs. Later, Ly Theam Teng founded the Khmer Writers Association, with its bi-monthly publication Ecrivains Khmers (“Khmer Writers”), and contributed to the first Cambodian journal of literary studies, Kambuja suriyā - a monthly publication of the Buddhist Institute.

With a solid knowledge of Chinese, Vietnamese and French literature, Ly Theam Teng was active on the international scene, attending the 1958 Afro-Asian Writers’ Conference in Tashkent (then USSR) as part of the non-aligned movement encouraged by Prince Sihanouk. In 1962, he was invited to China by the China Writers Association, which gave him the opportunity of meeting with Chinese writers such as Yang Shuo, and of perusing older editions of Zhou Daguan’s travelogue.

Before the Khmer Rouge takeover in 1975, had published a biography of Khmer poet Krom Ngoy (1966), collected oral traditions in the Siem Reap area, and achieved the first comprehensive history of Cambodian literature, Outline of Khmer Literature Development (1972). He published his work on Zhou Daguan in 1972, later reprinted in various editions and now available in digital format at Angkor Database.

Married to Ly Thirak (maiden name Eam Kim Houy 穗金惠), with whom he had five children, Ly Theam Teng was arrested by the Khmer Rouge in 1975 and died of exhaustion in 1978. After the war, his widow and one of their sons helped researcher and translator Uk Solang to find his preparatory notes for his translation of Zhou Daguan, as he was studying the Khmer phonetic origin of certain terms used by the Chinese chronicler.

Ly Theam Teng’s contribution has been highlighted by Cambodian scholars such as Khing Hoc Dy. Since 2021, a Center for Khmer Studies (CKS) research unit is working on his legacy.

Publications

- រឿង រំដួលភ្នំគូលេន, ប្រលោមលោក [Romduol Phnom Kulen, novel] ភ្នំពេញ, ១៩៥៤ (Phnom Penh, 1954)

- រឿង រស្មីចិត្ត, ប្រលោមលោក [Reaksmey Chet, novel] ភ្នំពេញ, ១៩៥៥(១៩៥៤) (Phnom Penh, 1954, published 1955)

- រឿង ព្រះបរមរាជា, ប្រលោមលោក [The King’s Story, novel] ភ្នំពេញ, ១៩៥៥ (Phnom Penh, 1955)

- រឿង សិរីស្វេតច្ឆត្រ, ប្រលោមលោក [Srey Svetchhat, novel] ភ្នំពេញ, ១៩៥៥, (១៩៥៤) (Phnom Penh, 1954, published 1955)

- រឿង សុបិន្តពេលយប់, ប្រលោមលោក [Night Dreams, novel] ភ្នំពេញ, ១៩៥៥ (Phnom Penh, 1955)

- ពង្សាវតារខ្មែរសង្ខេប, សិក្សាកថា [A Brief Khmer Genealogy, study] ១៩៥៩ (Phnom Penh, 1959)

- អក្សរសាស្រ្តខ្មែរ, សិក្សាកថា [Khmer Literature, study] ១៩៦០ (Phnom Penh, 1960)

- ពង្សាវតារប្រទេសកម្ពុជា, សិក្សាកថា [Chronicles of Cambodia, study] ១៩៦៤ (Phnom Penh, 1964)

- រឿងភ្នំស្រីវិបុលកេរ្តិ៍(ខេត្តសៀមរាប) [Phnom Srey Vibol Ker, Siem Reap], editor

- រឿង ឆ្លងពពកស្អាប់, ប្រលោមលោក [Dark Clouds, novel] ភ្នំពេញ, ១៩៦៦ (Phnom Penh, 1966)

- រឿង នារី និងបុប្ផា, ប្រលោមលោក [The Story of Neary and Bopha, novel] ភ្នំពេញ, ១៩៦៧ (Phnom Penh, 1967)

- Edited text of និរាសនគរវត្ត Niras Nokor Wat, Kampuchea Suriya, Phnom Penh,1967

- វិវត្តន៍នៃអក្សរសាស្រ្តខ្មែរ, សិក្សាកថា [Evolution of Khmer Literature, study] ១៩៧២ (1972)

- អ្នកនិពន្ធខ្មែរ ដែលមានឈ្មោះល្បី [Famous Khmer Writers, eversion at elibrary of cambodia]

- កំណត់ហេតុរបស់ជីតាក្វាន់ អំពីប្រពៃណីនៃអ្នកស្រុកចេនឡា [Zhiv Takwan Diary, translation], Phnom Penh, 1972 – 1973 (3d edition)]

- សៀវភៅ អ្នកនិពន្ធល្បីឈ្មោះរបស់ខ្មែរ, សិក្សាកថា [Outline of Khmer Literature Development, study], ភ្នំពេញ, ឆ្នាំ១៩៧២ (Phnom Penh, 1972)