En sampan sur les lacs du Cambodge et a Angkor

by Frédéric Gas-Faucher

A colorful description of Cambodia, its geography and its people at the turn of the century.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Typographie et Lithographie Barlatier, Marseille

- Published

- 1922

- Author

- Frédéric Gas-Faucher

- Pages

- 135

- Language

- French

pdf 7.3 MB

The author, a French educator acquainted with French Protectorate officials, presents himself as a “mere tourist” in this book, and nevertheless several notations are worth the reading. We’ll start with incidentals that led us to further research:

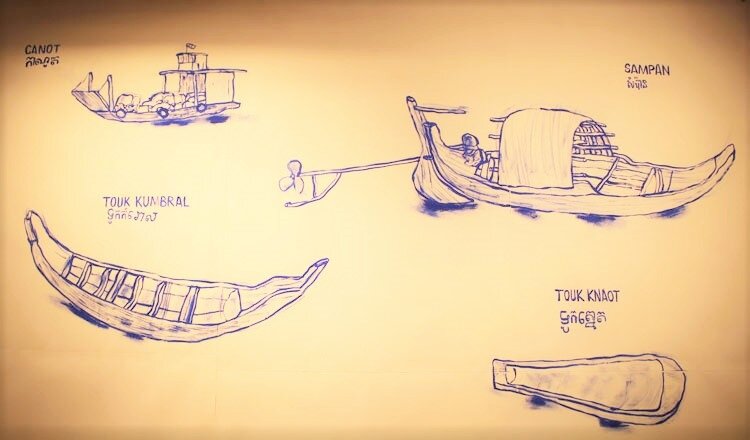

About the Cambodian Sampan

The word sampan is here used indescriminately. Known as សំប៉ាន (saampan) in Cambodia, this fishing and transportation type of boat was probably introduced in the region by Malay sailors and fishermen. The term comes from the Cantonese sāam báan (三板), meaning literally “three planks” (same etymology in English and French, which led someone to wrongly assume that the Khmer word came from the French). In his research onthis word etymology, Pascal Médeville notes that Cambodian linguist Chuon Nath described the sampan as made of “five planks”.

Yet during his navigation the author probably used other kind of boating devices, such as the traditional Khmer pirogue, ទូក (touk), studied and detailed in an essay by Hoc Cheng Siny in 2001. Curiously, Gas-Faucher insists in a footnote that “the modern sampan is similar to those pictured on Angkor bas-reliefs, where the oarsmen stand erect the same way as the gondoliers of Venice”.

Different types of Cambodian traditional boats pictured by artist Christophe Reynart (IFC Phnom Penh, 2017) Below: Boats on Bayon bas-reliefs.

The Duchess of Aosta in Angkor

Recalls the author: “Il y a un grand hótel à Pnom-Penh. Il est admirablement situé en face du débarcadère [this was the Grand Hotel Manolis] et de sa terrasse on domine le panorama mouvant du fleuve. M. Joucla nous fit un accueil empressé et mit à notre disposition les appartements réservés aux hôtes de la Résidence: de grandes chambres, avec salon et salle de bains. J’occupai celle que venait de quitter la duchesse d’Aoste,à son retour d’Angkor.”

This notation allows us to determine that the author’s trip took place in January or February 1914. Helene, the Princess of Orleans, a notorious woman traveler who had just published her book on Africa, visited Angkor on her Far Eastern journey that she later described in Vers le soleil qui se leve (Ivrea, F. Vassonne, 1916 and 1918).

Ironically, the Princess had a chance to see the Royal Ballet perform after returning to Phnom Penh from Angkor. At her arrival in Cambodia on Jan. 24, the illustrious traveler’s meeting with King Sisowath I had been last-minute canceled because the sovereign was feeling “tired” (“Poor man”, mischievously noted the Duchess of Aosta, “he is sixty-four years old, is a great smoker of opium…and has four hundred women to content”.

A few days later, Gas-Faucher, who had marveled at King Sisowath’s Royal Ballet dancers in Marseilles in 1905, was disappointed to hear all festivities and audiences at the Royal Palace had been canceled due to the King’s illness…

Helen of Orleans in a canoe in Mozambique, 1909 (coll. Edward W. Hanson)

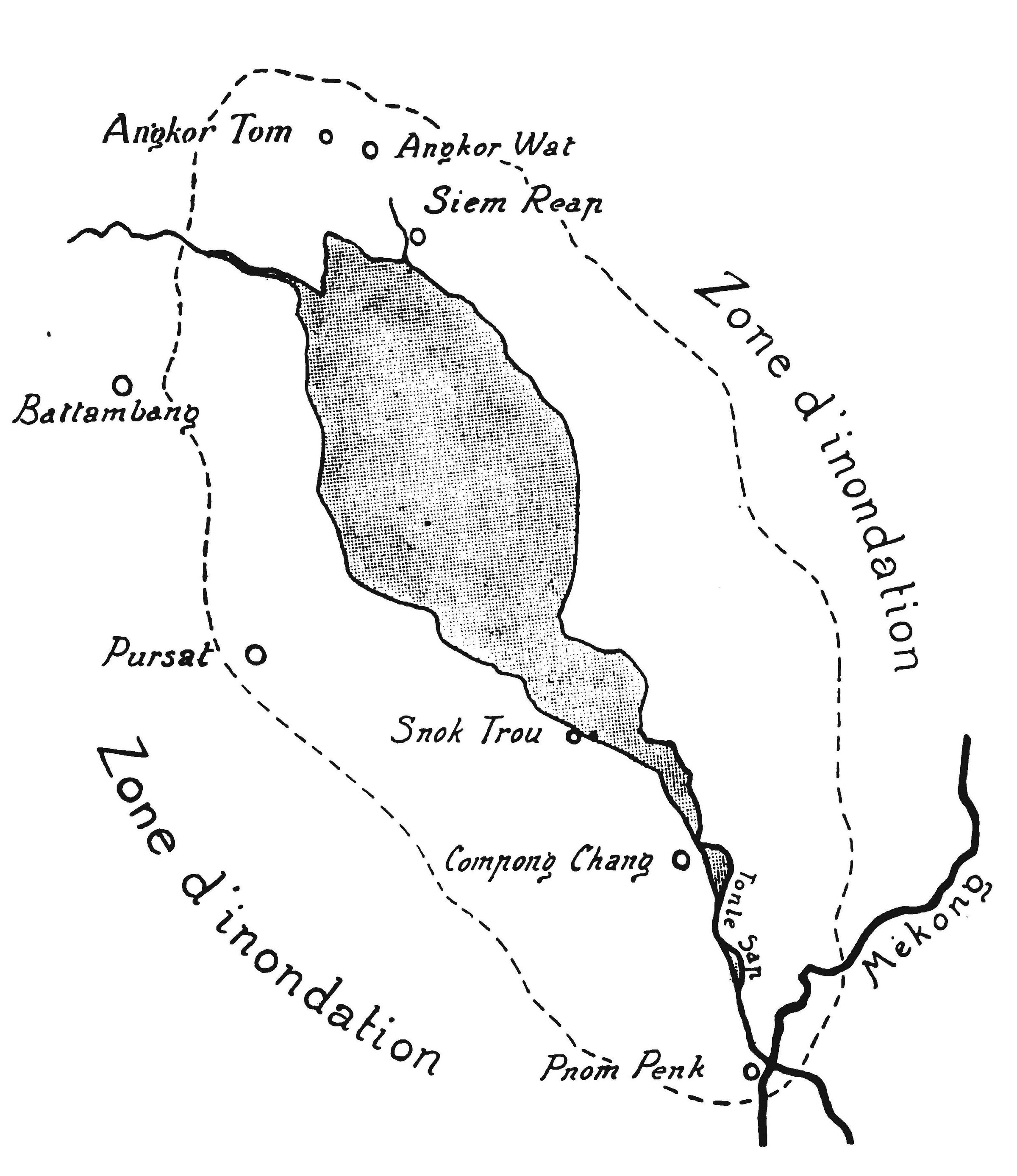

Floating villages on the Tonle Sap

Gas-Faucher is probably the first Western traveler in the modern period to not only allude to the floating villages but also describe them in detail: “Le village est en grande partie flottant; c’est-à-dire que les cases reposent sur des radeaux de bambous, fixés par des ancres. Les chaussées sont remplacées par des planches simplement posées sur l’eau, en long et en large. Sur ce sol mouvant les femmes, les hommes chargés marchent en équilibre, pendant qu’à côté barbotent les canards. Les enfants, qui traversent en courant, font de fréquentes culbutes; mais ils sont peu vêtus et savent tous nager à partir de cinq ans. [“The village is largely floating; that is to say that the huts rest on bamboo rafts, maintained in place by anchors. The causeways are replaced by boards simply lined up on the water, lengthwise and broadside. On this shifting ground the women, the laden men walk in balance, while the ducks paddle nearby. The children, who run along the causeways often fall in the water; but they are scantily clad and all know how to swim from the age of five.]

“Lorsque le vent fait clapoter l’eau, tout le village danse: les rues, les maisons, les canards, les cochons…et les gens. Une partie cependant s’appuie sur la boue du rivage et forme une longue avenue de paillotes sur pilotis. Là ce sont les habitations qui sont stables, au moins provisoirement, et la population qui est flottante. Au moment des grandes eaux, elle émigre en emportant les cases démontées.” [“When the wind rises waves on the water, the whole village dances: streets, houses, ducks, pigs…and people. A certain part, however, rests on the mud of the shore and forms a long avenue of straw huts on stilts. There it is the dwellings which are stable, at least temporarily, and the population which is floating. When the waters are high, they emigrate carrying the dismantled huts.”]

On this author’s (qyite approximative) map, we can see that the flooded areas were much larger at the turn of the 20th century than nowadays.

The Heavens and Hells Gallery at Angkor Wat

The author was one of the first to take interest in Angkor Wat South-East Gallery, the “Heavens and Hells” bas-reliefs: “Sur un panneau, long de vingt mètres, trois voies sont tracées conduisant, les deux premières au paradis, la troisième aux enfers. La conception du paradis brahmanique est peu démocratique. On у voit des seigneurs et de belles dames, richement vêtus et installés dans d’élégants pavillons; il se font éventer par leurs serviteurs et assistent à des danses, en mangeant des gâteaux et des fruits. [“On a twenty-meters long panel, three paths lead, the first two to paradise, the third to hell. The Brahmanic conception of paradise is not very democratic. We see lords and beautiful ladies, richly dressed and installed in elegant pavilions; they are fanned by their servants and attend dances, while eating cakes and fruit.]

“L’enfer est plus curieux. Des inscriptions classent et énumèrent les fautes commises. Il y a des peines terribles pour les incendiaires, les assassins, les menteurs, les ivrognes, les gourmands. Il y en a pour ceux qui volent les fleurs, le riz et les parasols; pour ceux qui ensorcellent les femmes d’autrui, qui osent “s’approcher des épouses des savants”…” [“Hell is less conventional. Inscriptions classify and enumerate the faults committed. There are terrible penalties for arsonists, murderers, liars, drunkards, gluttons. There are some for those who steal flowers, rice and parasols; for those who bewitch other people’s wives, who dare “to approach the wives of scholars”…”]

All in all, his remarks on Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom are rather informed, since he was received in Angkor by the great archaeologist and conservationist Jean Commaille, spelled “Commailles” in the book.

- Read more about Mekong River wooden boats design and building techniques, a study by Ken Preston.

- This account of circumnavigation on the Tonle Sape Lake came some fifty years after Vice Admiral Bonard, then French governor of Cochinchina, claimed he was aboard “the first European steamboat to have flown a [French] flag” on the lake when he traveled from Saigon to Angkor during the 1862 fall season (in “Angcor en septembre 1862,” Revue Maritime et Coloniale, Feb. 1863, 244 – 247). Bonard had claimed a few months earlier, in Feb. 1861, the storming of Bien Hoa and Baria against the Annamite forces.

Tags: Tonle Sap, dance, King Sisowath, French travelers, Protectorate, boats, navigation, Mekong River, women travelers, heavens and hells, floating villages, rivers, archaeology

About the Author

Frédéric Gas-Faucher

Frédéric Gas-Faucher (1876, Marseille, France — 25 Feb. 1939, Marseille) was a French educator traveler whose relation of Cambodia in the 1910s, En sampan sur les lacs d’Angkor et du Cambodge (1922), has been consistently quoted and referred to.

From his book, we know that his interest for Cambodia and Indochina bagun in 1907, when he visited the Marseilles Exposition Universelle and was introduced to King Sisowath I and his entourage. He often refers to “Monsieur Outrey”, without further elaboration, the latter possibly being Ernest Outrey (1863, Constantinople — 1934, Paris), Résident-Général in Phnomh Penh from 1910 to 1914, or more probably Maxime Outrey (1864, Miliana, Algeria -?), Ernest’s cousin, an archaelogist and administrator who had first served in Indochina in the 1880s, the French official in charge of liasing with King Sisowath on behalf of the Ministry of Colonies and a supervisor of Angkor in the 1910s.

He was also close to Félix-Gaspard Faraut, using several of the latter’s drawings in his book.