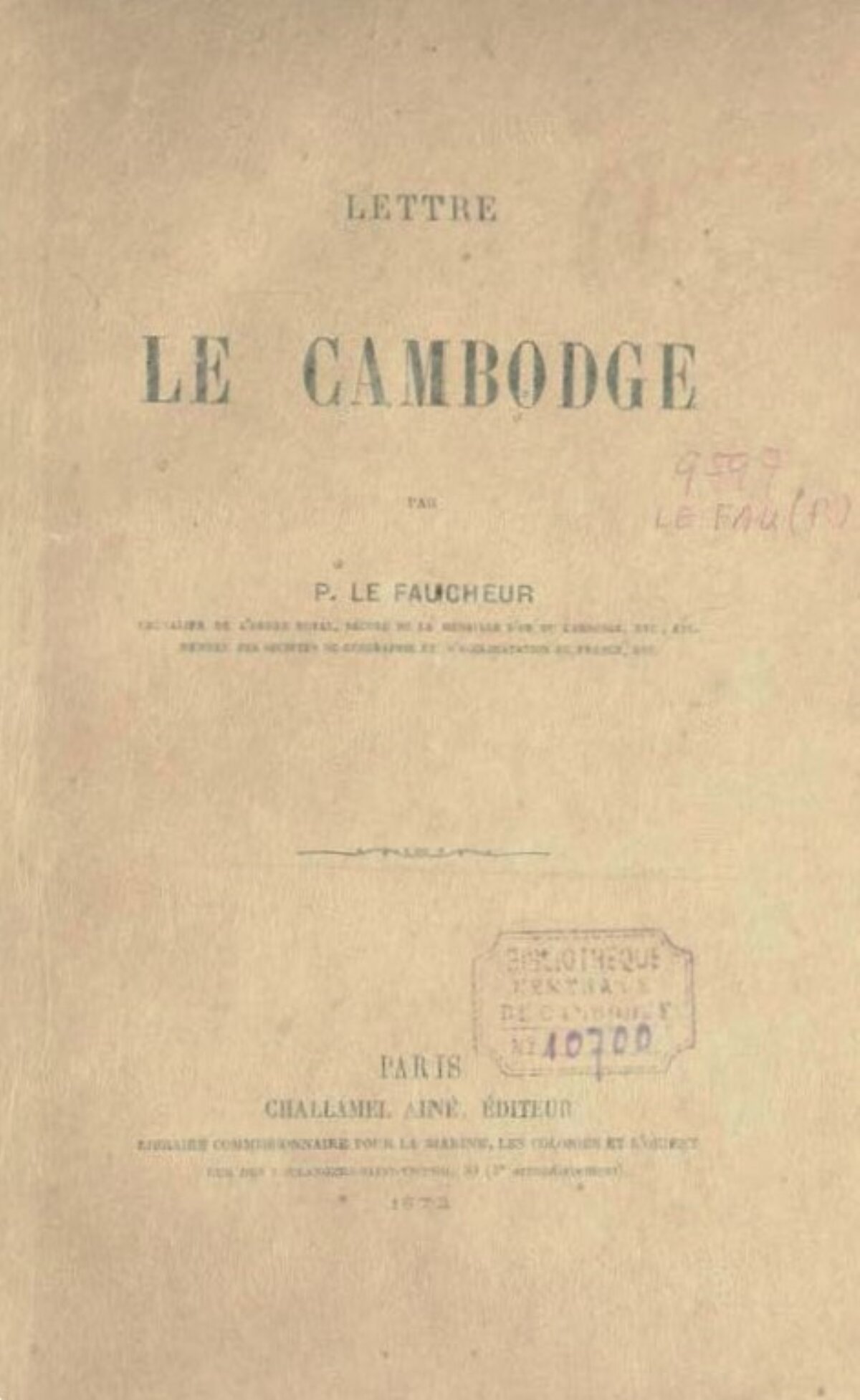

Lettre: Le Cambodge

by Paul Le Faucheur

A short and telling plea for the colonial economic development of Cambodia.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Challamel, Paris.

- Edition

- photographed document courtesy of Jean-Jacques Donard | ADB digital version.

- Published

- 1872

- Author

- Paul Le Faucheur

- Pages

- 70

- Language

- French

pdf 6.2 MB

Often referred-to but never published in extenso until now and here, this short book penned by the Frenchman who claimed to be “the architect of the new Royal Palace” in Phnom Penh gives us some indications with some indications on King Norodom’s entourage, his character (brushing a quite laudative portrait of His Majesty at a time the French administrators called him “notre roitelet” [“our kinglet”]), and the connections between Cambodian elites and French entrepreneurs. Penned around 1870, this “letter” to a French friend is the work of an active exponent of economic development for “protected” Cambodia, with the lingering fear that the British Empire, through Siam, could supplant French interests in the area.

About Angkor, for instance, the author stated

Le premier objet qui frappé la vue est une porte immense avec deux galeries intérieures; dès lors l’œil n’aperçoit plus que des palais, des pagodes, des massifs de 60 mètres d’épaisseur, avec des galeries supérieures, enfin un luxe d’ornementation incroyable. Un seul monument comporte trente-quatre tours; il faudrait des mois entiers pour se faire une idée exacte de toutes ces beautés. Dans l’art des Grecs et des Romains rien d’aussi grandiose né m’a frappé l’imagination; aussi, dans l’intérêt de la science, serait-il à désirer, je le répète, que l’on se hatât de faire des recherches, car de véritables forêts croissent au milieu de ces ruines, et le temps y continue lentement, mais sûrement, son œuvre de destruction. Malheureusement je crains bien que, malgré les instances de notre excellent docteur Pichon de Saigon, ce travail né soit pas entrepris par des Français; je tiens en effet d’excellente source que les Anglais de Bangkok sont sur le point d’organisen une sérieuse expédition dans ce but.

Parmi les Cambodgiens, les uns disent que ce sont les anges qui sont les auteurs de ces constructions; d’autres, et je les crois dans le vrai, en attribuent l’origine au fameux roi lépreux (Neac Somdack Comlong), qui l’aurait fait bâtir pour payer à un bonze une promesse de guérison. Ce serait ce der- nier qui aurait fait aussi construire la pagode de la ville d’Angcor; sa statue s’y trouve, et elle frappé tout le monde par la noblesse de sa physionomie. On pense que ces constructions auraient élé élevées pendant le neuvième siècle, alors que le royaume du Cambodge était à l’apogée de sa gloire. Il faudrait un merveilleux talent de description pour dépeindre exactement ces antiquités; il faudrait en outré des connaissances architecturales et archéologiques que je suis loin de posséder. (p 29 – 30)

[“The first object that strikes the view is an immense door with two interior galleries; from then on the eye only sees palaces, pagodas, massifs 60 meters thick, with upper galleries, altogether an incredible luxury of ornamentation. A single monument has thirty-four towers; It would take whole months to get an exact idea ofall these beauties. In the art of the Greeks and Romans nothing so grandiose has struck my imagination; also, in the interest of science, it would be desirable, I repeat, that we hasten to carry out research, because real forests grow in the middle of these ruins, and time continues there slowly, but surely, his work of destruction. Unfortunately I fear that, despite the entreaties of our excellent Doctor Pichon of Saigon, this work will not be undertaken by the French; I have in fact an excellent source that the English in Bangkok are about to organize a serious expedition for this purpose.

“Among the Cambodians, some say that the angels are the authors of these constructions; others, and I believe them to be true, attribute its origin to the famous leper king (Neac Somdack Comlong), who had it built to pay a monk a promise of healing. It would be the latter who would have also built the pagoda of the city of Angcor; his statue is there, and it strikes everyone with the nobility of its physiognomy. It is believed that these constructions would have been erected during the ninth century, when the kingdom of. Cambodia was at the height of its glory It would take a wonderful talent of description to accurately depict these antiquities; it would also require architectural and archaeological knowledge that I am far from possessing.” (p. 29 – 30)]

This humility about lacking scientific knowldege on Angkorean temples contrasts with the opening lines of the books, where the author boasts about his command of Khmer language and his closeness to Cambodian royalty:

J’habite le Cambodge depuis neuf ans; dès le commencement et en très peu de temps je pus parler la langue, et plus tard j’appris à l’écrire. La langue cambodgienne est recto tono et aussi facile à apprendre que le malais. Elle diffère complétement de la langue annamite que je parle aussi, celle-ci, au contraire, excessivement difficile à retenir. J’ai toujours été auprès du roi, mes propriétés se trouvent sur le terrain du palais, j’ai pour voisins les ministres; par conséquent, nul mieux que moi né peut donner des renseignements exacts et complets sur ce pays.

[“I have lived in Cambodia for nine years; from the beginning and in a very short time I was able to speak the language, and later I learned to write it. The Cambodian language is recto-tono and as easy to learn as Malay. It differs completely from the Annamite language that I also speak, the latter, on the contrary, excessively difficult to remember. I have always been close to the king, my properties are on the palace grounds, my neighbors are the ministers; therefore, no one better than me can give exact and complete information about this country.” [p 1]

His presentation of the country is succint yet rather to the point:

Le royaume du Cambodge ou de Khmer est situé entre le 10 et le 13 degré de latitude Nord, le 101 et le 105 degré de longitude Est. Les Annamites l’appellent Kaomen, les Siamois Kammen, les Chinois Tang-po-cha, tous les Malais Cambodia, les habitants écrivent Campuchea, le roi sur son cachet par exemple. De là nous avons fait dériver Cambodge. Il a pour limites au nord le royaume de Siam et le Laos, à l’ouest le golfe de Siam, au sud la basse Cochinchine, et à l’est il s’étend indéfini-ment vers les populations sauvages qui habitent les montagnes et les vallées comprises entre le Mé-Kong et la Cochinchine. Sa population est d’environ 2 millions d’habitants en y comprenant les Malais, les Annamites et les Chinois. Les Malabars, que l’on voit toujours dans ces mers arriver les premiers partout où se trouvent des chances de gain à faire dans le commerce, commencent déjà à s’y établir en assez grand nombre.

[“The kingdom of Cambodia or Khmer is located between 10 and 13 degrees north latitude, 101 and 105 degrees east longitude. The Annamites call it Kaomen, the Siamese Kammen, the Chinese Tang-po-cha, all the Malays Cambodia, and the inhabitants write Campuchea, for example on the King’s stamp. Our “Cambodge” stems from that. Its limits to the north are the kingdom of Siam and Laos, to the west the Gulf of Siam, to the south lower Cochinchina, and to the east it extends indefinitely towards the wild populations who inhabit the mountains and the valleys between Mé-Kong and Cochinchina. Its population is approximately 2 million inhabitants, including the Malays, the Annamites and the Chinese. The Malabars, who we always see in these seas arriving first wherever there are chances of profit to be made in trade, are already beginning to establish themselves there in fairly large numbers.”[p 2]]

Setting apart some oblique references to his setbacks with French administrators, the book is highly positive in regards with the current and future of Cambodia, with a blithering assessment of the Christian missionaries in Cambodia, an a warm acknowledgement of the positive influence of Buddhist monks, who

né s’occupent jamais de politique, en quoi ils diffèrent des brahmanes, dont on sait que la religion est la source du bouddhisme. Nos prêtres devraient bien prendre modèle sur eux, et à ce propos, je né dirai qu’un mot de nos missionnaires, qui depuis deux cents ans se sont implantés au Cambodge sans résultat; car les Cambodgiens sont inconvertissables, et il y a à cela une raison puissante: c’est que presque tous ont revêtu le costume des bonzes, je n’en connais pas un seul qui se soit fait catholique. La mission, comme le dit très-bien le Père Bouillevaux, qui y a passé douze années et se trouve actuellement à Saïgon, se compose d’un ramassis de gens de sac et de corde. Certes, j’en sais quelque chose; ayant confié à ces misérables une dizaine de mille francs pour des coupes de bois, j’en ai été frustré le mieux du monde. (p 41)

[“never concern themselves with politics, in which they differ from Brahmins, whose religion as we know is the source of Buddhism. Our priests should model themselves on them, and in this regard, I will only say a word about our missionaries, who for two hundred years have been established in Cambodia without any result; because the Cambodians are unconvertible, and there is a powerful reason for this: almost all of them have taken on the costume of monks, and I do not know a single one who has become Catholic. The mission, as Father Bouillevaux, who spent twelve years there and is currently in Saigon, says very well, is made up of a collection of villainous people. Certainly, I know something about it, having entrusted these wretches with around ten thousand francs for cutting wood, which left me utterlyfrustrated.” (p.41)]

And his mention of the Brahmanic caste of the Baku manifests his mastering of the Phnom Penh Royal Palace mores:

Je dirai quelques mots d’une caste d’anciens Cambodgiens qui portent les cheveux longs et qu’on nomme des Bakŭ. Ce sont des espèces de prêtres qui se relèvent par série pour garder l’épée du roi, épée mystérieuse très-courte et en fer très-grossier, mais qui inspire une grande terreur aux Siamois. C’est par leurs soins qu’elle a pu être conservée jus- qu’à nos jours. Tout quasi-prètres qu’ils sont, ils peuvent se marier; ils disent de certaines prières qu’ils né peuvent entièrement expliquer né les comprenant pas très-bien eux-mêmes; ils sont de toutes les cérémonies; ils préparent l’eau sacrée pour l’usage du roi et pour la cérémonie de la coupe des cheveux des enfants du roi. Ils sont respectés; mais vu leur petit nombre ils sont destinés à disparaître d’ici à peu d’années. (p 43)

[“I will say a few words about a caste of ancient Cambodians who wear their hair long and are called Bakŭ. These are a kind of priests who to take turns to guard the king’s sword, a very short mysterious sword made of very coarse iron, but which inspires great terror in the Siamese. It is through their care that it has been preserved until today. Even as quasi-priests as they are, they can marry; they say certain prayers which they cannot fully explain, not understanding them very well themselves; they are part of all ceremonies; they prepare the sacred water for the use of the king and for the ceremony of cutting the hair of the king’s children. They are respected; but given their small number they are destined to disappear within a few years. (p.43)]

A puzzling end

“Vous voudrez bien me pardonner le décousu de cette lettre. Ce n’est pas un livre, ce n’est pas même une brochure; c’est une simple lettre avec toutes les licences de forme que ce titre comporte. Je vous écris au hasard de la plume en me laissant librement aller au courant, peut-être un peu capricieux, de mes impressions et de mes souvenirs” [“I hope you’ll forgive me for this rambling text. This is not a book, not even a brochure, but a simple letter with all the licenses this form involves. I am writing to you following my pen, letting myself go with the flow, perhaps a little capricious, of my impressions and memories”], had conceded the author to his anonymous destinary. However, the closing pages are surprising: a “Letter on Cambodia by a Cambodian” under the name of “James”, document allegedly translated [from the Khmer, or the Vietnamese?] by “le malheureux capitaine Savin de Larclauze dont la mort tragique en 1867 impressionna si vivement la population coloniale.” [“the unfortunate Captain Savin de Larclauze whose tragic death in 1867 deeply impressed the colonial community.”] Benjamin Clément Savin de Larclause (23 Oct. 1835, Céaux, France — 7 June 1866, near Tayninh Fort) was a French officer with the Naval Infantry general staff, former director of Canton French police, and Inspector of Indigenous Affairs in Tayninh when, attempting to break a crowd of Pu-Cambo’s supporters — a monk who claimed his rigths to access the Cambodian throne -, he was killed by firearm shot. He authored a map of Cambodia, but not much more of him is known to us.

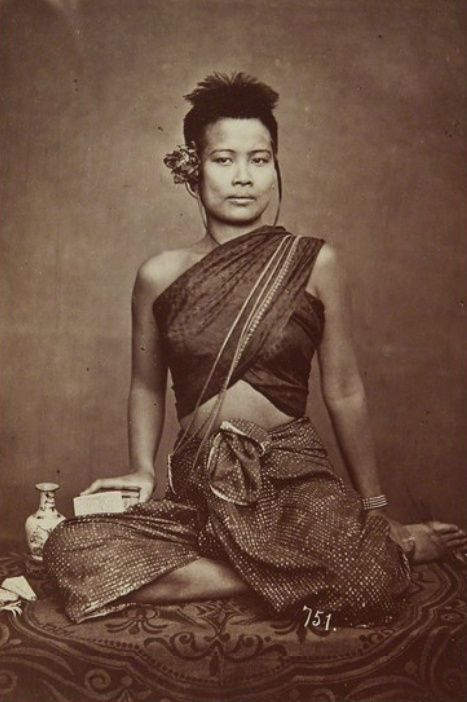

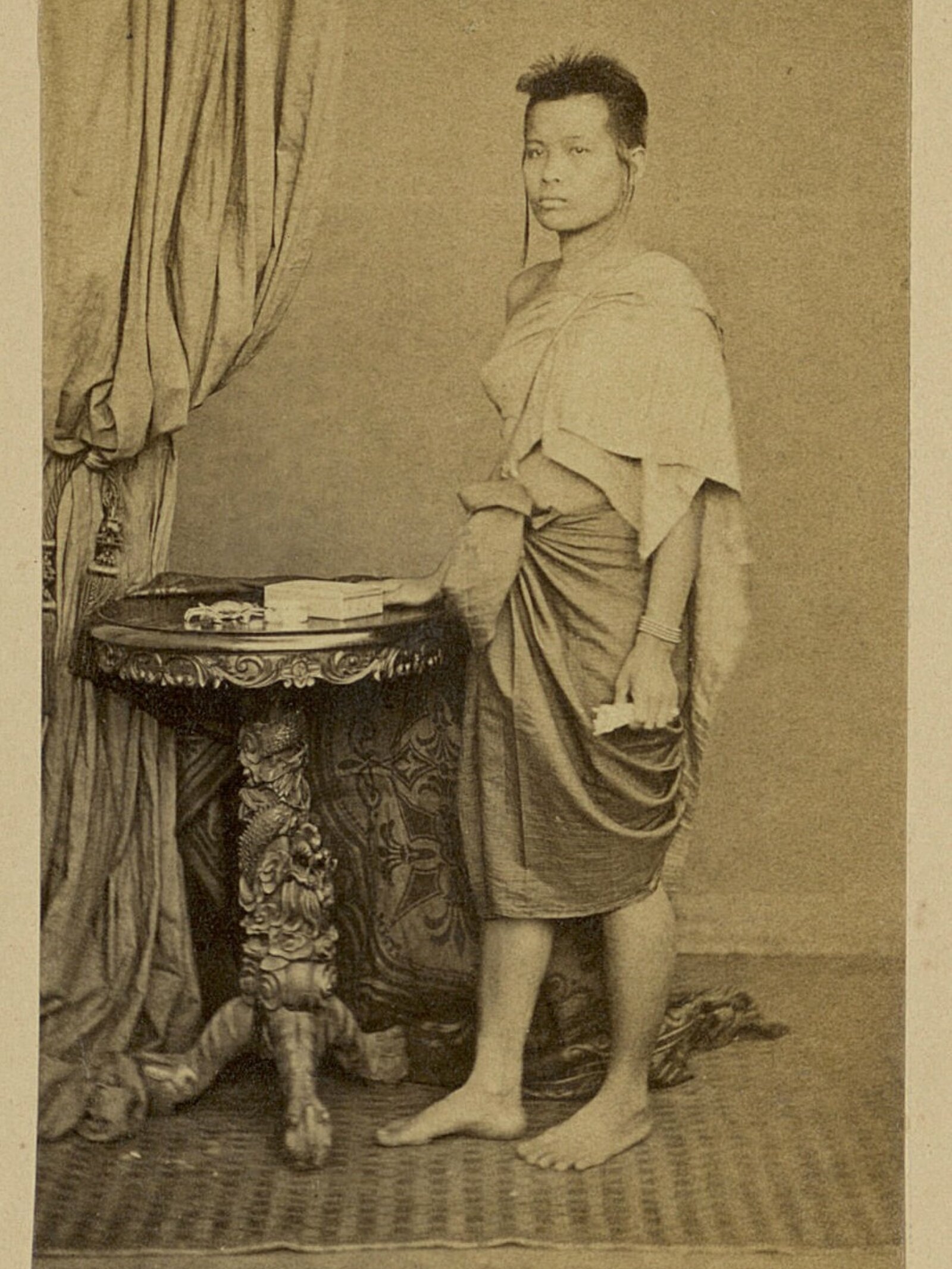

Mi-Soc (Neang Sok), the enigma of the “Cambodian woman” revealed

At the end of his short book, the author shared four photographs, two of Angkor Wat, one a standing portrait of King Norodom, and the first one of a “Cambodian woman (Mi Soc)”. They were all by photographer Emile Gsell, part of a series of 21 images of Cambodia (and 26 of Indochina) reproduced in the lavish album Cochinchine et Cambodge Admiral Rigault de Grenouilly, upon his nomination as Minister of the Navy, presented Empress Eugénie in 1867.

Recently, this portrait of Le Faucheur’s legitimate wife has inflamed the Net, with some Net denizens pretending it was in fact depicting a Siamese (Thai) lady-in-waiting, some others “a black Vietnamese woman”, and some more “the concubine of a French colonial officer.” It is not.

Neang Sok (“Mi”, “little mother”, being a slightly derogative way of referring to Cambodian women sentimentally involved with foreigners at that time) was a “tall” Royal Ballet dancer, her height meaning she was prone to perform male roles in the Khmer classical repertoire, especially Neayrong. She was rumored to be a favorite of King Norodom, who handed her to Le Faucheur in recognition of his work on the new Royal Palace. Their daughter, Malis Le Faucheur, married Veang Thiounn [Chhoun], the Minister of the Palace, in 1884. [communication by Ms. Yanine Pok, direct descendant of the latter mentioned marriage, to Royal Ballet dancer Sok Nalys on behalf of Angkor Database, June 2024. Ms Pok called Sok “Lok yāy”, “Esteemed Grandmother”.]

Thiounn Mumm, grandson of Veang Thiounn-Malis Le Faucheur, has confirmed this lineage to researcher Jean Jacques Donard before his passing in 2022. The most comprehensive study on this quite unique couple’s lineage was offered by Marie Aberdam in her 2019 PhD thesis, Élites cambodgiennes en situation coloniale, essai d’histoire sociale des réseaux de pouvoir dans l’administration cambodgienne sous le protectorat français (1860−1953), Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne; Centre d’Histoire de l’Asie Contemporaine). About the social status of women such as Neang Sok, she notes that “entre 1872 et 1897, le portrait social des compagnes des Français du protectorat paraît s’être étoffé : alors qu’elles pouvaient appartenir au Palais de Norodom dans les années 1870, elles né sont plus considérées que comme des femmes de mauvaise vie à la fin des années 1890.” [“between 1872 and 1897, the social profile of the Protectorate Frenchmens ‘compagnes’ seems to have expanded: while they could belong to the Palace of Norodom in the 1870s, they were only considered as women of ill repute at the end from the 1890s.”] Neang Sok, with her past at the Royal Palace, held a better position than two other famous ladies of the time, Neang Teat, Jean Moura’s concubine, and Neang Ruong , concubine of Albert Louis Huyn de Vernéville, Resident-Superior from 4 July 1889 to 24 January 1894, and from 4 August 1894 to 14 May 1897.

Tags: French Protectorate, French traders, women, Phnom Penh Royal Palace, King Norodom I

About the Author

Paul Le Faucheur

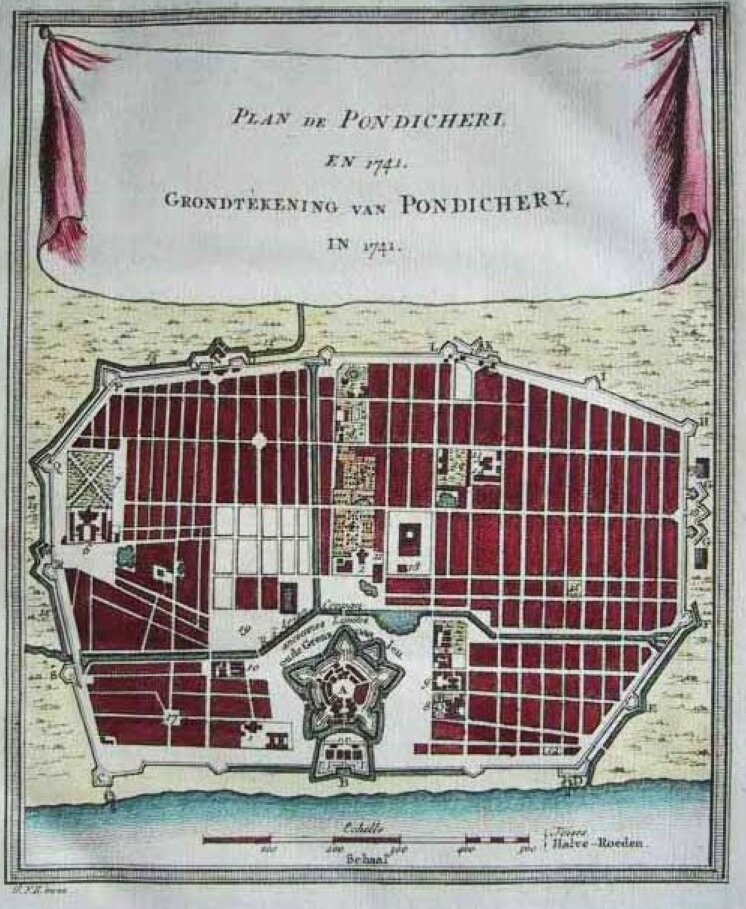

Paul François Joseph Le Faucheur (31 Oct. 1833, Pondichéry (Puducherry), French Indies — 8 May 1874, Phnom Penh) was a French Navy officer, an entrepreneur and and businessman who became close to HM King Norodom I of Cambodia in the 1860s-1870s, and was involved in several dealings regarding the building of the new Phnom Penh Royal Palace.

The son of Joseph Jean François Le Faucheur (28 Sept. 1807, Puducherry ‑19 Jan. 1861, Saint Denis, La Reunion), superintendent adjunct of the French Navy and Magdeleine Aimée Baude de Bunnetat (12 July 1808, Rivière-du-Rempart, Mauritius Island ‑1842), he was held as a “metis” (mixed-race individual), labeled a “Créole” by French chroniclers . His parents had married on 10 Feb. 1831 at Tharangambadi, Tamil Nadu (then British Indies), and divorced around November 1838. Later on, his father married a Mauritius woman, Malvina Tardivel (1815−1873), who was to give him eight more sons and daughters.

He was still in ‘Bourbon’ (Mauritius Island) in 1848, and claimed to have reached Cambodia in 1858. In his sole written testimony, Lettre: Le Cambodge, he recounted an expedition to the “wild lands of Stung Treng” from which he claimed to have brought back “un grand nombre d’objets en usage dans ces grandes tribus sauvages, armes, idoles, bijoux, ustensiles, etoffes, instruments que je remis au ministere de la Marine au mois d’octobre 1864.” [“a large number of objects in use amongst these large wild tribes, weapons, idols, jewelry, utensils, fabrics, tools that I handed over to the Ministry of the Navy in October 1864.” It is on his way back to Phnom Penh — he claimed — that he stopped at Udong and was introduced to King Norodom –he was also accused to rape an underage girl in the precincts of the Royal Palace. At that time, he viewed as an interloper (“coureur d’arroyos”, a French way to say “buccaneer”), was depicted as such in Jean Moura’s official correspondence, and French Governor de la Grandiere attempted to have him expelled from Cambodia.

In 1865, H.G. Kennedy, a young British consular officer based in Cambodia and accompanying photographer John Thomson to Cambodia, met Le Faucheur (he mispelled his name, ‘Le Foucheur’) in Phnom Penh and noted in his report: “I was told by a Frenchman in his Majesty’s service that the King’s income may be reckoned at about 1000 l. a month; but though Mr. Le Foucheur had ample opportunities for framing an estimate on the subject, I yet conjecture that he may have been anxious, so far as possible, to give me unfavourable impressions respecting the general affluence of the country. […] M. Le Foucheur, the architect of the new Palace, is paid also, as I believe, by the French, but nominally for services as an explorer of the country. His Majesty has besides two interpreters in his employ ; the first one a Spaniard, and the second a Portuguese half-caste. […]”

Le Faucheur was early in envisioning the commercial potential of the vast forests of Cambodia’s Northeast, setting up the first large sawmill in Chhlong, a village south of Kratie on the Mekong River. Later, he developed a limestone quarry in Châu Đốc, on the road from Saigon to Phnom Penh. He made sure the timber and other building materials were bought for the construction of the new Phnom Penh Royal Palace, starting from 1865.

Presenting himself as the King’s personal architect, he seems to have acted as an productive contractor, persuading His Majesty to chose brick-and-mortar over traditional wood for the new Royal Palace in Phnom Penh: “Après trois ans d’instance, le roi s’est enfin decide a construire la ville en brique; a mon depart j’avais deja construit quarante maisons, soixante autres etaient presque acheves, et j’avais passé avec M. Roustan, negociant a Saigon, des contrats pour l’erection de deux cent autres maisons qui devront etre achevees le 31 decembre 1872. J’ai fait batir un poste de police, un marche couvert. Des ordres ont ete laissés pour l’achevement des pavillons de plaisance pour le jardin du roi, on en termine d’autres pour les ambassadeurs, etc…Les ateliers du roi contiennent cinq machines a vapeur qui ont deja rendu d’immenses services. Ces travaux sont executes par moi sur les plans qui me sont donnes et dessines par le roi lui-meme, qui a adopte presque en entier notre architecture europeenne, et il obtient des resultats tres satisfaisants en l’alliant a celle de son pays.” [“After three years of persuasion, the king finally decided to build the city in brick; when I left I had already built forty houses, sixty others were almost completed, and I had signed with Mr. Roustan, merchant in Saigon, contracts for the erection of two hundred other houses, which must be completed by December 31, 1872. I have had a police station completed, and a roofed market. Orders have been left for the completion of the pleasure lodges for the king’s garden, others are being completed for the ambassadors, etc. The king’s workshops contain five steam engines which have already provided immense service. These works are carried out by myself after the plans given to me and designed by the king himself, who has almost entirely embraced our European architecture, and has obtained very satisfactory results by combining it with that of his country.”] (Lettre Le Cambodge, p 33 – 4)

Very active on the Phnom Penh business scene in the first years of the Protectorate, he became so close to the King that Norodom I gave him for spouse a famed dancer of his Royal Ballet, Anak Sok (often called ‘Mi’ Sok, a Khmer word then attributed to Cambodian women who had married foreigners), who was rumored to be one His Majesty favorites. According to Ms Yanine Poc, one of her great-grand daughters, Anak Sok was tall and slender, which predisposed her to perform the Neayrong role. [communication to ADB, July 2024]

Their daughter, Malis Le Faucheur, was to marry Minister of the Palace Veang Thiounn. Around 1915, Thiounn Yang, their daughter, married Poc Duch’s son, Poc Hel, in a matrimonial alliance between dignitaries that lasted several decades.

More about Paul Le Faucheur here.