Le nouveau guide du Musée national de Phnom Penh | The New Guide to National Museum-Phnom Penh | មគ្គុទ្ទេសក៍ថ្មី សំរាប់សារមន្ទីរជាតិ - ភ្នំពេញ

by Samen Khun

An early illustrated guide to the rich collection of Khmer art at the National Museum of Cambodia.

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, Ariyathoar Printing House, Phnom Penh.

- Edition

- 2d edition, French edition.

- Published

- 2007

- Author

- Samen Khun

- Pages

- 152

- Languages

- English, French, Khmer

This useful guide — of which a new expanded edition is much needed, as the National Museum of Cambodia សារមន្ទីរជាតិ (NMC) has received so many important artworks restituted in the last decade -, starts with a short yet detailed chronicle:

History of the Museum

“The Museum was built in 1916, during the period of the French Protectorate in Cambodia (1863−1953). The original design was prepared by George Groslier. The inauguration ceremony took place on April 13, 1920 under the auspices of His Majesty King Sisowath of Cambodia in the presence of François-Marius Baudoin, French Resident Superior in Cambodia. Today two marble plaques in French and Khmer commemorating this date are on display on the walls either side of the interior staircase.

The Museum was first housed on the grounds of the Preah Sisowath School and was called the Phnom Penh Museum. It was then transferred to the east gallery of the museum and was named the Museum Krong Kampuchea Dhipati. To honor the French Governor General of Indochina, the Krong Kampuchea Dhipati Museum was renamed the Albert Sarraut Museum. In 1966, the name was again changed, this time to the National Museum of Cambodia. The Museum was renamed the Archaeological Museum in 1979. Finally, during the administration of Museum Director Mr. Pich Keo, the name of National Museum of Cambodia was officially reinstated.

The edifice has housed both the Museum and the Faculty of Fine Arts for many years and various works completed by the Cambodian art instructors and ‘students form an integral part of the structure. Instructors and students of the Faculty are responsible for the ornamentation of twelve wooden windows and three pairs of large sculpted doors, as well as the windows of the western wall of the bronze gallery. These last are composed of paintings representing various characters from traditional folk tales. Since 1917, the School of Art Decoration of the Royal Palace was located in three main galleries (south, west and north) of the museum. Known in Khmer as the Sală Rachana, it was then moved to the southern campus of the Faculty of Fine Arts.

The Museum was initially directed by French curators: George Groslier was the first, followed by Pierre Dupont, Jean Boisselier and Madeleine Giteau (1956−1966). In 1951 France officially transferred the management of the Museum to Cambodia. From 1966 to 1975, two Cambodian curators, Mr. Chea Thay Seng ជា ថៃសេង and Mr. Ly Vou Ong លី វូអុង, were in charge. The East Gallery of the Museum was renovated in 1969 under the direction of Mr. Chea Thay Seng. The renovation included a new upper level for administrative offices and a library as well as an underground storage area.” A number of curators succeeded each other since January 7, 1979: Mr. Kan Man ខាន់ ម៉ាន់, Mr. Ouk Chea អ៊ុក ជា, Mr. Ouk Sun Heng អ៊ុក ស៊ុនហេង and Mr. Pich Keo ពេជ កែវ. On 26 September 1996, the responsibility for the Museum was transferred from Mr. Pich Keo to Mr. Khun Samen, under the auspices of H.E. Nuth Narang. Minister of Culture and Fine Arts.

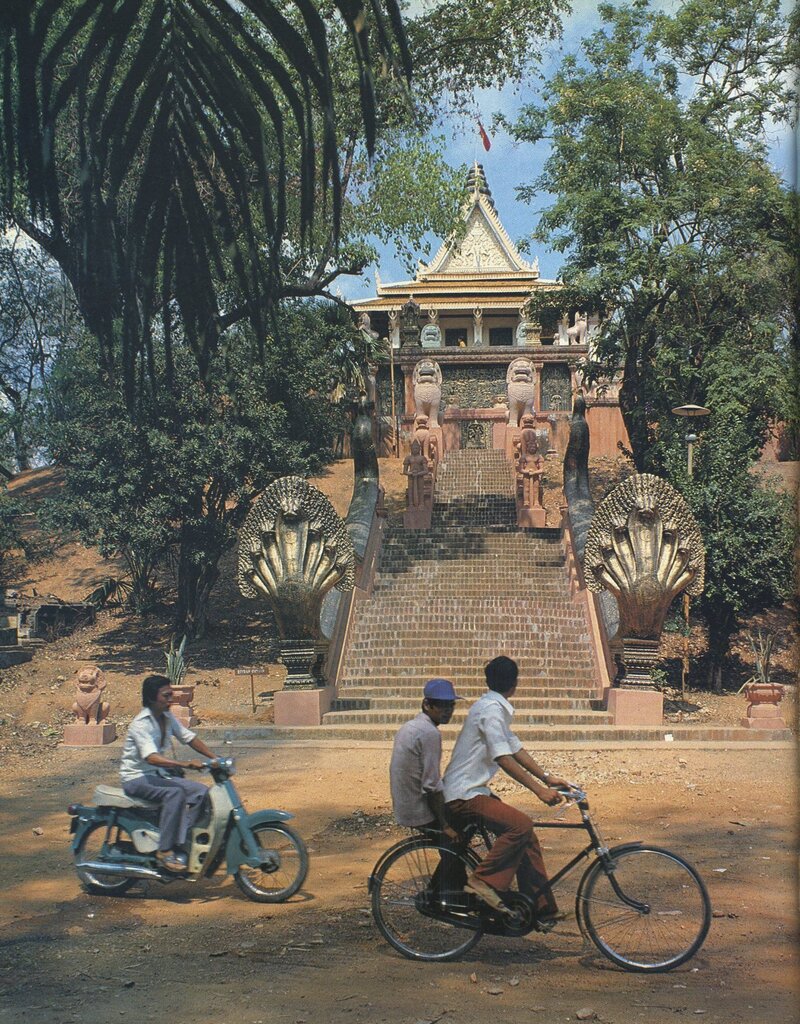

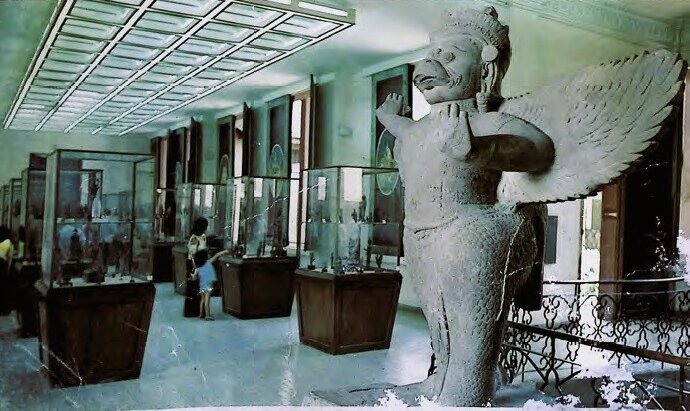

A rare photograph of the museum’s main hall shortly after its reopening in 1979, part of the book ការស្ថាបនាប្រទេសកម្ពុជាក្រោយគ្រោះមហន្តរាយ [Cambodia: Rebuilding After Disaster], 1988. The photo was taken around 1984.

A rare photograph of the museum’s main hall shortly after its reopening in 1979, part of the book ការស្ថាបនាប្រទេសកម្ពុជាក្រោយគ្រោះមហន្តរាយ [Cambodia: Rebuilding After Disaster], 1988. The photo was taken around 1984.

Additional Notes [Angkor Database]

- Chea Thay Seng was appointed in 1966 as the first Cambodian Director of the National Museum and Dean of the newly created Department of Archaeology at the Royal University of Fine Arts. In an interview with The New York Times in 1971, he mentioned that about 200 crates containing artwork from Angkor and other places endangered by fighting were now stocked in the Museum storage, and many other sculptures had been buried near the corresponding temples to escape looting, and added:

“The biggest problem we face is that Thai art dealers have set up businesses along the Thai-Cambodian border where they buy stolen and smuggled statues for a pittance from Cambodian smugglers and then resell them in Bangkok. The real problems are great European museums. “As long as they want Khmer art so badly, there will always be that force pulling it out of Cambodia through illicit exporters.” [Ivan Peterson, “Trying to Save a Nation’s Heritage”, The Straits Times, 25 February 1971, p 10.]

- Chea Thay Seng and co-curator Ly Vou Ong perished in Tuol Sleng in 1976.

- Closed and abandoned during the Khmer Rouge era, the museum was tied up and reopened to the public on 13 April 1979 as Museum of Art and Archeology. Museum directors of the post-civil war era were Kann Mann, Ouk Chea and Ouk Sun Heng.

- Pich Keo, who had been the first Cambodian curator of Angkor since 1979, and Khun Samen ឃុន សាម៉េន, the present guide’s author, were succeded as NMC Director by (Ms.) Oun Phalline អ៊ុន ផល្លីន, Hab Touch ហាប់ ទូច, Kong Vireak គង់ វីរៈ, and later on by Chhay Visoth ឆាយ វិសុទ្ធ, the director at the date of writing (2025).

- After the war, the first international exhibition of pieces from NMC collection was held at the National Gallery of Australia in 1992.

- Since 2004, the Leon Levy Foundation/CKS National Museum Collection Inventory Project has developed towards an online comprehensive cataloguing of the collection, which has grown from some 1,000 pieces in 1920 to nearly 17,000 nowadays. Initiated by the late Darryl Collins and developed since 2010 by conservation advisor Bertrand Porte, the museum registrar team’s work was successively supervised by Khun Samen, Hab Touch, Oun Phalline and Kong Vireak, and the collection registery is available online.

- In 2021, as the global pandemic was raging, the NMC held its first online exhibition that included numerous photographs from its archive reflecting the history of the museum. ThmeyThmey online news collected several of those in a presentation in Khmer and (partly) English that was unfortunately taken down from the web at some point.

Art Period Classification

A Khmer art historian, the author follows the art style periodization developed by EFEO, sticking to a datation so precise that one can sometimes doubt its relevance. The fact that these “styles” seem to never overlap in time leads to several questions, such as: would they rather represent “schools” of architects, displaying the same vision, using the same techniques over time, and possibly operating in the same geographical area? To which extent architectural and sculptural styles were edicted and supervised by rulers or elites of each time period? Especially with the Pre-Angkorian Period, to which extent did the Prei Khmeng style, for instance, differ so much from the Kompong Preah style? This is definitely material for further research and discussion.

PRE-ANGKORIAN PERIOD (2nd half of the 6th century – beginning of the 9th century)

Phnom Da Style (514−600)

Sambor Prei Kuk Style (600−650)

Prei Khmeng Style (635−700)

Prasat Andet Style (657−681)

Kompong Preah Style (706−800)

(TRANSITIONAL PERIOD)

Kulen Style (802−875)

ANGKORIAN PERIOD (9th century — 1431)

Preah Ko Style (875−895)

Bakheng Style (893−925)

Koh Ker Style (921−945)

Pre Rup Style (944−967)

Banteay Srei Style (967−1000)

Khleang Style (965−1010)

Baphuon Style (1010−1080)

Angkor Vat Style (1100−1175)

Bayon Style (1180−1230)

POST-ANGKORIAN PERIOD (1431 — present)

Here are the author’s considerations for the “Pre-Angkorian” and “Transitional” periods:

PRE-ANGKORIAN PERIOD (2nd half of the 6th century – beginning of the 9th century) and TRANSITION PERIOD (802−875)

“It is generally accepted that this period begins with the fall of Fu-nan and ends, not with the founding of Angkor, which did not take place until the last years of the 9th century, but with the introduction (in the first half of the 9th century) of the rites upon which the kingship of Angkor was to be based. The oldest (Buddhist) images are no earlier than the middle of the 6th century. The somewhat later (early 7th century and period following) Brahminic monuments already exhibit some of the traditional features of Khmer architecture. There exist only a few fine examples of Pre-Angkorian art. This period marks the beginnings of the Khmer world, in which a distinct personality gradually affirms itself, while globally remaining under foreign influences. The belief in the cult of the ‘god-king’, do not as yet exist. Nevertheless, the art of this period lays down the basis for sculptural symbolism, and inaugurates architectural forms which will be reused and later improved upon. Pre-Angkorian statuary witnesses an Indian influence, but anatomical representation is less dramatic. Sculptors used a support arch for figurative representations with many arms. Stone sculpture is characterized by its delicacy of execution, as well as its respect for plastic and anatomical form.”

Phnom Da Style (514−600)

“Sculpture: Evolution of statuary from high relief to free-standing sculpture. The works display typical Indian movement of the torso, often with a support arch to provide stability. | Architecture: The architecture of the sixth century is almost unknown. Brick terraces were found at Angkor Borei dating from the Funan period. No other remains have been found in Cambodia to date.”

Sambor Prei Kuk Style(600 – 650)

“Sculpture: The statuary presents little evidence of sensuality or erotism and is rather modest. The statuary is modeled with great sensibility. Temple decoration is mostly composed of bas-reliefs. | Architecture: The basis of Khmer architecture is the sanctuary (Prasat). This sanctuary can be found either isolated or in groups (very often 5 sanctuaries), it is composed of individual elements such as lintels, columns, pediments and decorative panels. The temples are sometimes octagonal, square or retangular.”

Prei Khmeng Style (635−700)

“Religion: Shivaism and Mahayana Buddhism . An inscription (791) was found in Siem Reap, which mentions the image of the bodhisattva Lokesvara. It is supporting evidence of the existence of Mahayana Buddhism in Cambodia. | Sculpture: The sculptures are generally smaller than the previous styles. The supporting arch is still present. | Architecture: This style witnesses some changes in architectural decoration, in continuity with the Sambor Prei Kuk style.”

Prasat Andet Style (657−681)

“Religion: Shivaism and linga cult, Mahayana Buddhism loses influence among the people. | Sculpture: Artistic representation codes change; the search for delicacy and slenderness witness great sharpness of observation. Hindu sculptures are carved in the round. The linga is increasingly represented. | Architecture: This style has no specific characteristics of architectural decoration.”

Kompong Preah Style (706−800)

“This art form reflects a dark period in the history of Cambodia caused by the dislocation of Tchen-la into two kingdoms. | The style of Kampong Preah is similar to that of Prei Khmeng, although an increasing number of statues are carved in a plainer fashion, in particular the folded edge of the sampot and the lengthwise fold. | Religion: Hinduism | Sculpture: Human sculpture is stylized. On the walls of temples, some isolated figures appear (Javanese or Cham influences). [About a Durga statue of unknown origin (Ka. 318)] : The presence of the supporting arch, evidence of which can be seen in the marks at the back of the head, and the two-armed shoulders indicate that this deity is Durga. The almond-eyes, sharp curved eyebrows, breasts, folds beneath the breasts, slender hips and, lastly the cylindrical mitre are characteristics of a classic Kampong Preah style sculpture. The simplified fold and pleats of the garment show great elegance. The face expresses natural beauty, with its curved upper lip and dimple in the chin. On her forehead, that the statue has probably already been consecrated. | Architecture: The “temple mountain” structure seems to appear at this time (Ak Yum).”

Kulen Style (802−875)

“Jayavaraman II unified the country and declared the Khmer kingdom secure. Mahendraparavata (present-day Phnom Kulen) and Hariharalaya (present-day Roluos) were the central cities of Jayavaraman II. The Kulen style is a transitional style which commenced in the Pre-Angkorian period and concluded in the Angkorian period. | Religion: Hinduism, cult of Shiva, God-King (Cakravartin). | Sculpture: Becomes more formalized and less natural. The body of the statue is solid and the chest cleaved. The face is square and the weight balanced on the left leg, with the right left set slightly forward. The supporting arch is no longer necessary. The first headdresses, the symbols of royalty become characteristic of the Angkorian period.”

1/ General view. 2/ Main exhibition hall in 2024, with some of the artefacts restituted to Cambodia.

The Saga of the Banteay Srei Vishnu Statue

In the global history of museology, the Phnom Penh Museum holds a special place for many reasons, including

- the worldwide major collection of ancient Khmer art was built-up in a relatively short time period and following the pace of archeological discoveries, which explains why the labelling and inventory numbering varied over time and had to be fine-tuned along the way;

- the ever-expanding collection had to be accommodated in a relatively small-sized, historic building not always suited to the requirements of a modern museum, which explains why proper lighting and clear display setting remained a challenge, while many important artworks still to be kept in storage due to lack of space;

- in typical Cambodian fashion, surrounding gardens, inner courtyards and patios are intrinsic part of the museum’s character and charm;

- future ground expansion prospects are limited due to the museum’s central, symbolic location in the historic quarter of Phnom Penh, contrary to the Battambang Museum where land occupation and the city grid allowed for the development of a large new addition (to be opened in 2026).

In a short Activity Report entry dated Siem Reap, 31 Aug. 1949 [source: EFEO Online Archive], Henri Marchal, as he was welcoming in Phnom Penh Jean Boisselier, the new curator of the soon-to-be National Museum, kind of summarized all these issues with the following observations:

“CONSERVATION DU MUSEE ALBERT SARRAUT. — J’ai continué à prévoir une amélioration des pieces de sculptures situées dans l’aile Sud du musée et Mr. Boisselier, que j’ai rencontré a son arrivée à Phnom-Penh, arrivant de Saigon, m’a donné des suggestions fort intéressantes. Comme moi il déplore le mauvais éclairage qui empêche de voir certaines statues placées à contre-jour. Au sujet des renseignements généraux à placer a l’entrée de chaque galerie ou salle pour éveiller l’attention du visiteur et lui permettre d’apprécier les pièces exposées, Mr. Boisselier m’a remis les notices que Mr. Philippe Stern avaient fait placer au Musée de Toulouse et qui pourront, un peu abrégées, servir de modèles pour l’établissement de ces tableaux. Mr. Boisselier dans une visite attentive du Musée a relevé certaines inexactitudes d’étiquettes et m’a proposé une meilleure présentation de certaines pièces. Il m’a signalé le remplacement d’une tête sur une statuette par une autre. Il s’agit du fort beau et très intéressant Vishnu (B 265) provenant de Banteay Srei (cf. Mémoires Archéologiques Tome I Le Temple d’Içvarapura pl. 45 et Ars Asiatica XVI- Les Collections Khmères pl. XXVIII‑2). Comment a‑t-on pu casser la tête d’une statuette située dans une galerie du Musée pour lui substituer une autre de calibre analogue, ce qui explique que ce fait avait pu né pas attirer l’attention, la tête rapportée est d’un style pré-Khmer très différent de celui de la tête enlevée, qui était beaucoup plus belle. Où l’auteur de cet acte de vandalisme avait-il pu se procurer cette tête, comment avait-il pu faire un scellement pour la mettre sur le corps de la statue décapitée, il y a là un problème à éclaircir. Un des plus belles pièces du Musée Albert Sarraut se trouve actuellement de ce fait avoir perdu une grande partie de sa valeur. J’ai continué le travail de révision des fiches pour le catalogue et signé quelques pièces officielles.”

“CONSERVATION OF THE ALBERT SARRAUT MUSEUM. — I continued to devise an improvement of the sculptures located in the south wing of the museum and Mr. Boisselier, whom I met upon his arrival in Phnom Penh, arriving from Saigon, gave me some very interesting suggestions. Like me, he deplores the poor lighting which prevents one from seeing certain statues placed against the light. Regarding the general information to be placed at the entrance to each gallery or room to arouse the attention of the visitor and allow him to appreciate the artworks on display, Mr. Boisselier shared some of the labels Mr. Philippe Stern had placed at the Toulouse Museum; a little shortened, they could serve as models for these planned panels. Mr. Boisselier, in a careful visit to the Museum, noted certain inaccuracies in the labels and suggested a better presentation of certain pieces. He pointed out to me the replacement of a head on a statuette by another, namely the beautiful and very interesting Vishnu (B 265) from Banteay Srei (see Archaeological Memoirs Volume I — The Temple of Içvarapura pl. 45, and Ars Asiatica XVI- The Khmer Collections pl. XXVIII‑2). How could the head of a statuette located in a gallery of the Museum be broken off only to replace it with another of similar caliber — which explains why this fact could not have attracted attention as the added head is of a pre-Khmer style very different from that of the removed head, which was much more beautiful? Where could the author of this act of vandalism have obtained this head, how could he have made a seal to put it on the body of the decapitated statue, there is a puzzle to be solved. One of the most beautiful pieces of the Albert Sarraut Museum has currently lost a large part of its value as a result. I continued the work of revising the cards for the catalog and signed some pieces official.”

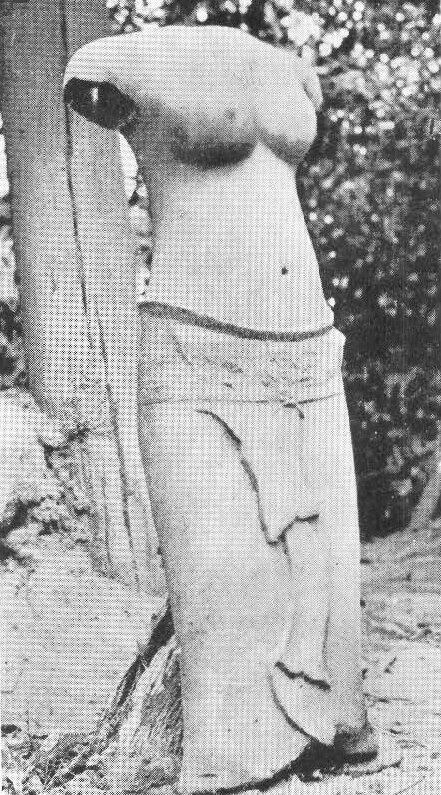

After inquiring with Bernard Porte, who was in charge of the development of the Museum’s online registry and the digitization of related documentation, it appears that this Vishnu statue was restored to its headless state at the time of its discovery in the Banteay Srei northern sanctuary and is currently kept in storage along with the ablution basin it was sent to the Museum in 1924, both artifacts still labelled “B. 265” as per the ancient registry [the statue “B 302.2” in the catalog made later by Boisselier]. The whereabouts of the original removed head remains unknown.

Vishnu (Inventory numbers Ka.108 / B.302.2 / B.265), sandstone, Angkor Wat style (12th C.), provenance “Siem Reap Province” in the catalog [Banteay Srei], H. 50.8, W. 18.2 cms, Weight 4.70 kg, NMC. And the ablution basin brought in together with the statue. [photos NMC]

Tags: National Museum of Cambodia, conservation, art history, Musee Albert Sarraut, museology, Khmer sculptures, Khmer arts, pre-Angkorean

Associated Items

Publicationsby Robert Dalet

Publicationsby Robert Dalet Publications

PublicationsSurvey of the Southern Provinces of Cambodia in the Pre-Angkor Era

by Haksrea Kuoch Publications

PublicationsFouilles en Cochinchine: Le Site de Go Oc Eo, Ancien Port du Royaume de Fou-nan [Excavations in Cochinchina: The Site of Go Oc Eo, Former Port of the Funan Kingdom]

by George Coedès Photos

PhotosCambodia 1980s in Photographs

by Alfred V. Lieberman

About the Author

Samen Khun

Khun Samen [or Samén] ឃុន សាម៉េន (b. 9 Sept. 1948, Prey Veng Province) is a Cambodian Professor of Khmer Art History and Museology who was the director of Phnom Penh National Museum (now National Museum of Cambodia) from 1996 to 2007, acting as a curator of the collection before. He was succeeded by, respectively, Hab Touch ហាប់ ទូច (b. 1963), Ms Oum Phalline អ៊ុន ផល្លីន (b.1951), Kong Vireak គង់ វីរៈ (b. 1972) and, since 2020, by Chhay Visoth ឆាយ វិសុទ្ធ (b. 1978).

Khun Samen authored the first comprehensive guide of the Museum published after the civil war (1st edition 2006, in English, French and Khmer). At that time, he was also the curator of the first major exhibition since the civil war, Preah Neang Tevi. He also curated Post Angkorian Buddha Statues exhibition in 2000 — now part of the permanent exhibition at the Museum and The Ganesa of the National Museum [co-curator with Bertrand Porte], also in 2000.

After his retirement from National Museum, Khun Samen has kept teaching Khmer methodology and Khmer iconography at Royal University of Fine Arts (RUFA), Department of Archaeology.

Publications

- [dissertation adviser] ការចុះបញ្ជីសារពើភណ្ឌ នៃវត្ថុសិល្បៈ នៅសារមន្ទីរជាតិភ្នំពេញ ចាប់ពីឆ្នាំ១៩៩៦ ដល់ ១៩៩៧ ដោយនិស្សិតនាក់ រំអង, សុខ ហ៊ុនលី, ដឹកនាំដោយសាស្ត្រាចារ្យ ឃុនសាម៉េន [Inventory listing of art objects at the National Museum of Phnom Penh from 1996 to 1997, by students Rom Ang and Sok Hunly], 1998.

- [preface to] Son Soubert, Olivier de Bernon, ព្រះគណេសរបស់សារមន្ទីរជាតិ —Les Ganesa du Musée National —The Ganesa of the National Museum, exhibition at the National Museum of Phnom Penh 20 March — 31 May 2000, Ministere de la Culture et des Beaux-Arts, Phnom Penh, 2000 [curated by Khun Samen and Bertrand Porte].

- Post Angkorian Buddha [photos by Darren Campbell], White Lotus Press, Phnom Penh, 2000.

- ពិព័រណ៍អចិន្ត្រៃយ៍ “ពុទ្ធបដិមា សម័យក្រោយអង្គរ” សម្ភោធពីថ្ងៃទី២៨ ខែតុលា ឆ្នាំ២០០០ នៅសារមន្ទីរជាតិ ភ្នំពេញ [The permanent exhibition “Post-Angkorian Buddha Statue” inaugurated on October 28, 2000 at the National Museum of Phnom Penh], 2001.

- The new guide to the National Museum — មគ្គុទ្ទេសក៍ថ្មី សំរាប់សារមន្ទីរជាតិ — ភ្នំពេញ — Le nouveau guide du Musée National, Phnom Penh, 1st ENG, KH, FR edition, Phnom Penh Dept. of Museums, Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, 2002. [repub. Ariyathoar, Phnom Penh, 2007].

- [dissertation adviser] ការប្រគល់មកវិញនូវចលនសម្បត្តិវប្បធម៌ពីបរទេស ដោយនិស្សិត ប៉ែន វក្ខានីត, ដឹកនាំដោយសាស្ត្រាចារ្យ សេងសោត, ឃុន សាម៉េន [The return of cultural heritage from abroad by student Pen Vakhanit, directed by Professor Seng Sot and Khun Samen] 2003.

- Preah Neang Tevi: Collections of the National Museum, Department of Museums, Phnom Penh, 2006.

- Prasat Preah Vihear, Japan Printing House, Phnom Penh, 2008 [photographs by Khun Samen and Nguon Sophal] .