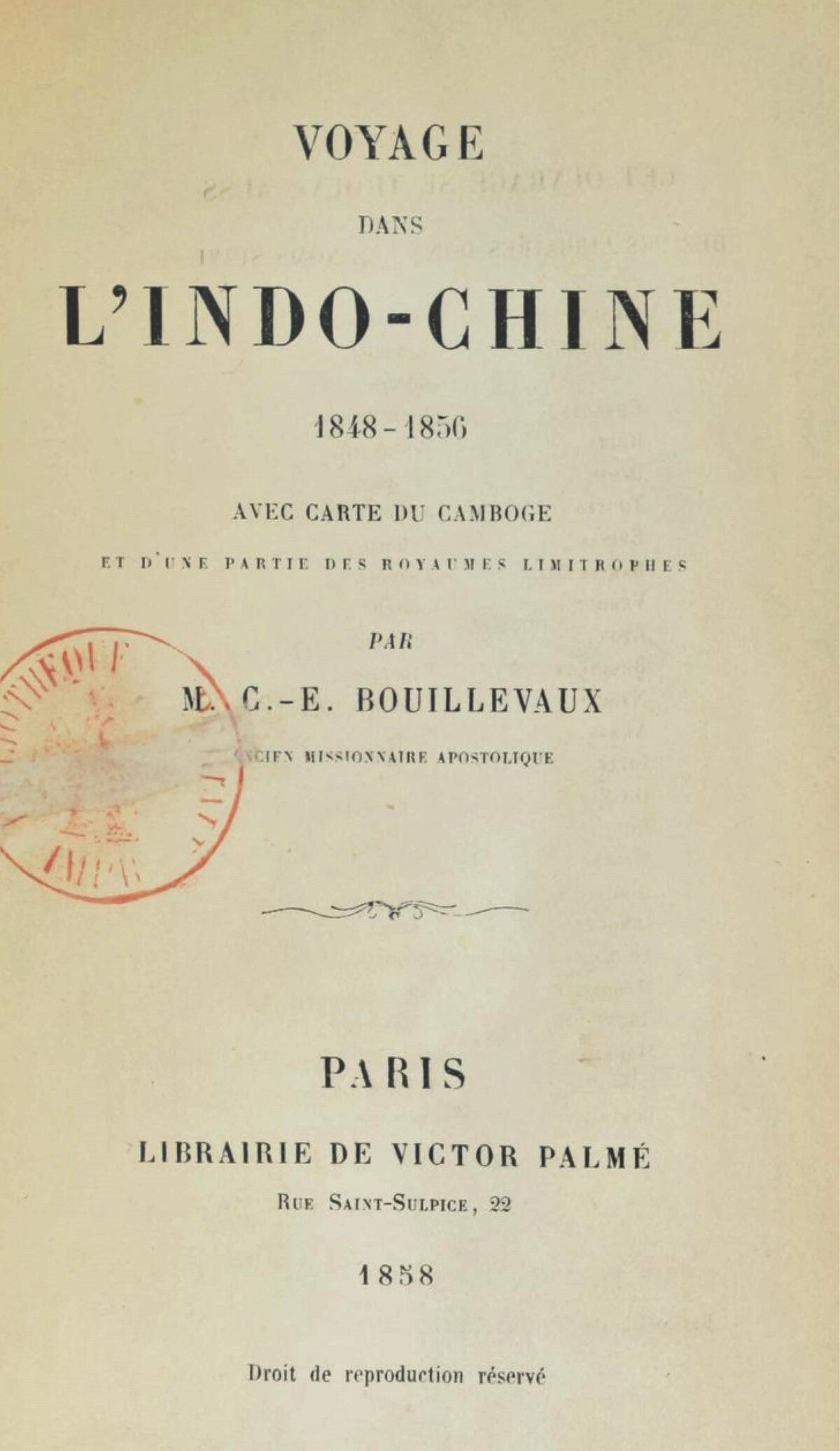

Voyage dans l'Indo-Chine, 1848-1856

by C.-E. Bouillevaux

Nearly twenty years before the "re-discoverer" of Angkor Henri Mouhot, a tireless Catholic missionary did visit the ancient Khmer city.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Victor Palme, Paris

- Edition

- via gallica.bnf.fr

- Published

- 1858

- Author

- C.-E. Bouillevaux

- Pages

- 381

pdf 29.6 MB

This is the first version of a travelogue that the author would develop in 1874, in L’Annam et le Cambodge, after noticing that Henri Mouhot’s relation of Angkor had triggered a huge interest in Europe.

Here, the parts of the book devoted to the ancient Khmer ruins are noticeably concise:

- “Apres avoir quitté la ville actuelle d’Angcor, je marchai, pendant plus d’une lieue, sur un sable brûlant qui mit mes pauvres pieds nus dans un triste état. Enfin, j’arrivai tout à‑coup, au sortir de la forêt, près d’une large chaussée de pierres de taille dont l’entrée était gardée par des lions de fantaisie. En suivant cette chaussée, qui traverse un étang où mangeait et se baignait un troupeau de buffles, je vis çà et là plusieurs petits kiosques en partie détruits ; les ruines en révélaient encore l’ancienne élégance. Je passai plus loin sous deux galeries quadrangulaires assez étroites, couvertes de sculptures, puis je me trouvai devant la pagode proprement dite. La pagode d’Angcor, assez bien conservée, mérite de figurer à côté de nos plus beaux monuments : c’est la merveille de la péninsule indo-chinoise. Ce temple bouddhique né ressemble nullement à une église d’Europe. Le principal corps de bâtiment présente un carré parfait; à chaque angle s’élève une belle tour qui se termine en dôme, et, au milieu, se dresse une cinquième tour plus haute que les autres. De grandes galeries dont les murs sont décorés de sculptures réunissent toutes ces tours. Il faudrait connaître l’art du dessin pour donner une idée exacte de la pagode d’Angcor: c’est un genre d’architecture tout particulier. Malgré sa bizarrerie , je trouvai ce monument grandiose, magnifique.” [“After leaving the modern city of Angcor, I walked for more than a league on burning sand which put my poor bare feet in a sad state. Finally, I suddenly arrived, on leaving the forest, near a wide causeway of hewn stones, the entrance to which was guarded by fancy lions. Following this causeway, which crosses a pond where a herd of buffaloes ate and bathed, I saw here and there several small kiosks partly destroyed; the ruins still revealed their former elegance. I passed further under two rather narrow quadrangular galleries, covered with sculptures, then I found myself in front of the pagoda itself. The pagoda of Angcor, fairly well preserved, deserves to appear next to our most beautiful monuments: it is the wonder of the Indo-Chinese peninsula. This Buddhist temple in no way resembles a church in Europe. The main body of the building presents a perfect square; at each angle s raises a beautiful tower that ends domed, and in the middle stands a fifth tower higher than the others. Large galleries whose walls are decorated with sculptures unite all these towers. One would have to know the art of drawing to give an exact idea of the Angcor pagoda: it is a very special kind of architecture. Despite its oddity, I found this monument grandiose, magnificent.”]

- “J’ai déjà dit que l’enseignement public, la prédication, n’existait pas chez les adorateurs de Sommocudom [Buddha in Khmer, according to the author] : une pagode n’est donc pas un lieu où l’on vient pour être instruit. Il paraî tque la pagode d’Angcor fut construite pour recevoir les livres sacrés venus de Ceylan. Sous la tour centrale, on voit une statue fort médiocre de Bouddha , donnée, dit-on, par le roy de Siam ; plusieurs autres statues de divinités indiennes, plus ou moins endommagées, reçoivent aussi, dans ce temple, les hommages des Cambogiens. Les pauvres idolâtres viennent, au jour des solennités, se prosterner devant tous ces monstres et brûler à leurs pieds des allumettes parfumées, tandis que les bonzes psalmodient leurs prières bali. Ces prêtres païens n’habitent plus maintenant les galeries de l’ancien temple ; ils demeurent dans de chétives cabanes en bois et en paille, tout près du superbe monument élevé par leurs pères. Pendant que j’admirais ces restes de l’antique splendeur du Camboge, les bonzes, appelés à l’office par le gong et les tam-tam, allèrent réciter en bali des prières qu’ils né comprenaient même pas.” [“I have already said that public education, preaching, did not exist among the worshipers of Sommocudom [Buddha in Khmer, according to the author]: a pagoda is therefore not a place where one comes to to be educated. It seems that the pagoda of Angcor was built to receive the sacred books from Ceylon. Under the central tower, one sees a very mediocre statue of Buddha, given, it is said, by the king of Siam; several others statues of Indian divinities, more or less damaged, also receive the homage of the Cambodians in this temple.The poor idolaters come, on the day of solemnities, to prostrate themselves before all these monsters and burn perfumed matches at their feet, while the bonzes intoning their Bali prayers. These pagan priests no longer inhabit the galleries of the ancient temple; they live in puny wooden and straw huts, very close to the superb monument erected by their fathers. While I admired these remains of the ancient splendor of Cambodia, the monks, called to the office by the gong and the tam-tam, went to Bali to recite prayers that they did not even understand.”]

- “Quand j’eus visité la pagode, je me dirigeai vers l’ancienne ville, autrefois séjour des rois. Bientôt je franchis les remparts qui subsistent encore et pénétrai dans l’enceinte, en passant sous une porte assez bien conservée. A environ une demi-lieue du mur d’enceinte, je trouvai des ruines immenses qu’on me dit être celles du palais royal. Le genre d’architecture paraît ressembler à celui de la pagode ; sur les murs, entièrement sculptés , je vis des combats d’éléphants, des hommes luttant avec la massue et la lance, d’autres tirant de l’arc et trois flèches en partant à la fois. Ces ruines né sont pas les seules : l’intérieur de l’ancienne ville en est couvert. Tout ce que j’ai remarqué à Angcor me prouve, jusqu’à l’évidence, que le Camboge a été autrefois riche, civilisé et beaucoup plus peuplé qu’il né l’est actuellement; mais toutes ces richesses ont disparu, cette civilisation est éteinte. Aujourd’hui, une épaisse forêt remplit l’enceinte de l’ancienne capitale et des arbres gigantesques croissent au milieu des palais en ruine. Il est peu de sensations plus tristes que celles qu’on éprouve en voyant déserts des lieux qui ont été jadis le théâtre de scènes de gloire et de plaisir. En réfléchissant sur les vanités du monde, je gagnai la maison du mi prey (chef de la forêt), qui voulut bien me donner, ainsi qu’à mes compagnons, l’hospitalité pour la nuit. Je me promenai , au déclin du jour, près de cette petite maison , qui s’élevait sur le même sol où avaient autrefois brillé les demeures splendides des princes du Camboge. Rêvant au passé, je vis le soleil se coucher derrière les grands arbres de la forêt : je comparais alors les teintes que la nuit effaçait dans le paysage à celles de la vie des peuples quand la gloire et l’espérance cessent de lui prêter la magie de leurs couleurs.” (pp 241 – 6) [“After visiting the pagoda, I headed for the ancient city, once the residence of the kings. Soon I crossed the ramparts which still remain and entered the enclosure, passing under a fairly well preserved door. About a half a league from the surrounding wall, I found immense ruins which I was told were those of the royal palace. The kind of architecture seems to resemble that of the pagoda; on the walls, entirely carved, I saw battles of elephants, men wrestling with clubs and spears, others shooting bows and three arrows at a time… These ruins are not the only ones: the interior of the ancient city is covered with them. Everything that I noticed at Angcor proves to me, to the point of evidence, that Cambodia was once rich, civilized and much more populated than it is now; but all these riches have disappeared, this civilization is extinct. Today, a thick forest fills the walls of the ancient capital and trees gi gigantic buildings grow in the midst of ruined palaces. There are few sensations sadder than those which one experiences in seeing deserted places which were formerly the theater of scenes of glory and pleasure. Reflecting on the vanities of the world, I reached the house of the mi prey (head of the forest), who was good enough to give me and my companions hospitality for the night. I walked, at the close of day, near this little house, which stood on the same ground where the splendid residences of the princes of Cambodia had formerly shone. Dreaming of the past, I saw the sun set behind the tall trees of the forest: I then compared the tints that the night erased in the landscape to those of the life of the people when glory and hope cease to lend it magic. of their colors.”]

- “Les habitants du royaume Khmer sont également supérieurs aux enfants d’Annam pour la musique vocale. On entend souvent ces derniers, en ramant sur le fleuve, chanter de leur voix nazillarde quelque refrain lubrique. Les Cambogiens n’ont pas, il est vrai, des chants beaucoup plus moraux, mais leur voix est plus claire et plus sonore, et leur langue se prête mieux à l’harmonie. Dans le palais de Sa Majesté Duong, premier du nom, il y a musique et théâtre au complet; j’ai entrevu quelquefois, bien malgré moi, ses concubines qui simulaient des batailles des anciens héros de l’Inde.”(p 320) [“The inhabitants of the Khmer kingdom are also superior to the children of Annam for vocal music. One often hears the latter, while rowing on the river, singing in their nazillarde voice some lustful refrain. The Cambodians do not have, it is true, songs much more moral, but their voice is clearer and more sonorous, and their language lends itself better to harmony. In the palace of His Majesty Duong, the first of his name, there is music and complete theatre; I have sometimes glimpsed, in spite of myself, his concubines who simulated the battles of the ancient heroes of India.”]

Tags: French explorers, French missionaries, Angkor Wat, pre-colonial Cambodia, Ang Duong, Ramayana, dance, religion

About the Author

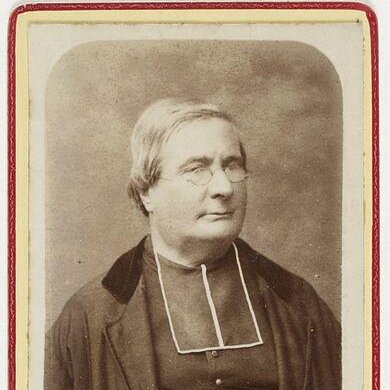

C.-E. Bouillevaux

Père Charles-Émile Bouillevaux (1 Apr. 1823, Montier-en-Der, France — 6 Jan. 1913, Montier-en-Der) was a French missionary and explorer who visited Angkor in December 1850 but waited until 1878 to publish an extensive account of his visit, Ma visite aux ruines cambodgiennes en 1850 (Mémoires de la Société académique indochinoise, T. 1), long after the popular interest encountered by Henri Mouhot’s description.

Reaching Cochinchina in 1849, he saw Angkor in 1850 and, a few months later, stayed with the Pnong (Penongs in the French transliteration) people in Northeastern Cambodia, traveled from Sambor to Ha-Tien in nine days, then stayed in Laos from 1853 to 1855, came back briefly to Cambodia in 1855 (Battambang). Following a brief return to Europe, he served as abbot of Choquan from 1867 to 1873. He was with the Société des Missions étrangeres, a French apostolic organization which had started to send missions to the Far East as early as 1661 (to Siam) and 1664 (to Cochinchina).

Contributing several articles to the periodical Courrier de Saigon, Bouillevaux published a Map of Cambodia, two relations of his travels in ‘Indochina’ (Voyages dans l’Indochine, 1848 – 1856 (Paris, Victor Palmé, 1858) and L’Annam et le Cambodge, Voyages et notices historiques (Paris, Victor Palmé, 1874).

Many historians of Angkor, including B.P. Groslier, have argued that Pere Bouillevaux did not immediately realize the significance of Angkor, even if he visited the Khmer ruins ten years before Henri Mouhot or John Thomson. George Coedès, however, granted him the privilege to be the first Western visitor of Angkor in the 19th century. As for Casimir-Edmee de Croizier, he wrote quite peremptorily in his 1878 brochure Les explorateurs du Cambodge: “La priorité pour l’exploration des monuments de l’ancien Cambodge lui appartient donc d’une façon incontestable, et son nom doit primer celui de tous les autres voyageurs.” [“The priority in the exploration of the monuments of ancient Cambodia irrefutably belongs to him, and his name must take precedence over that of all other travelers.”

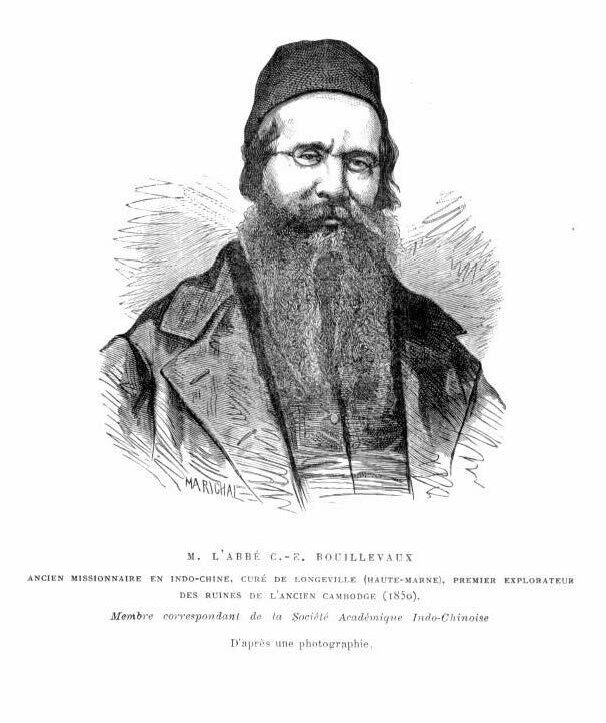

This portrait completed Bouillevaux’s paper ‘Ma visite aux ruines cambodgiennes en 1850’ [‘My visit to the Ruins of Cambodia in 1850’] in Mémoires de la Société académique de l’Indochine, t. I, 1877. The caption in French reads: “Abbot C.E. Bouillevaux, former missionary in Indochina, abbot of Longueville (Haute-Marne), first explorer of the ruines of Ancient Cambodia (1850).”