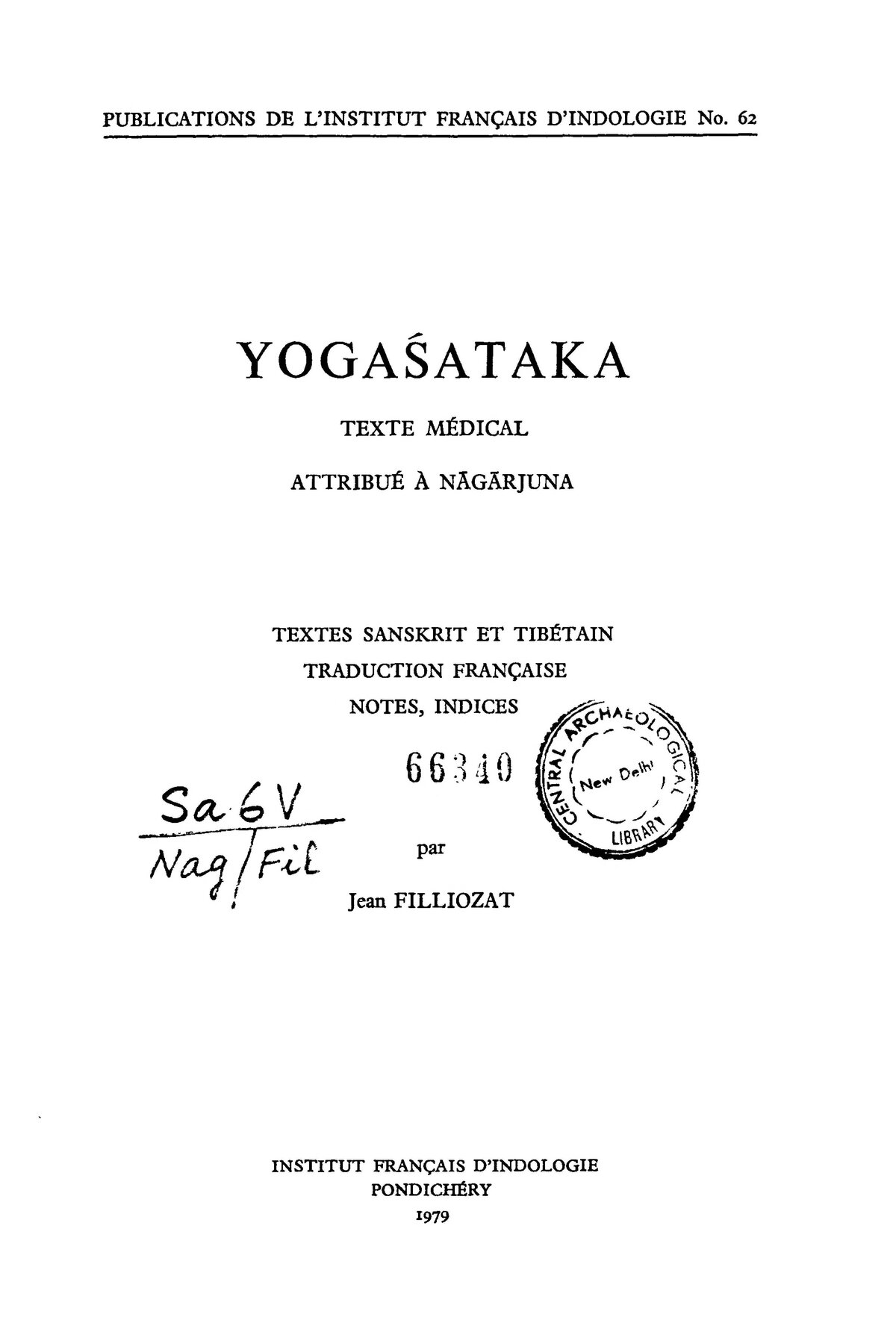

Yogaśataka or Yogashataka (योगशतक) is the name of an Ayurvedic treatise often attributed to written by Pandita Vararuci, ‘yoga’ meaning drug formulas and ‘śataka’ hundred [107, precisely, as the treatise is ordained in 107 stanzas]. It follows the classification of eight medical categories (astanga), adding to them one section on fever treatments (jvaracikitsa) and one on purgatives and laxatives (pancakarman).

In his introduction, the author does not give many insights on the ‘Nagarjuna’ to whom he attributes this text. Was he the famous Nagarjuna (Klu-sgrub in Tibetan), a Mahayana Buddhist monk and philosopher who articulated the doctrine of emptiness (shunyata) and is traditionally regarded as the founder of the Madhyamika (“Middle Way”) school, an important tradition of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy?

This celebrated philosopher’s personal life remains a mystery debated by researchers. He might have lived between 150 and 250 CE, and in multiple places in India, including in the south. One tradition holds that he founded a university on the banks of Krishna River, “a great centre of learning attracting a large number of teachers and students form distant parts of the world”, according to the Acharya Nagarjuna University [ANU, a modern center of higher education in Guntur, Andrah Pradesh, India]. Several scholars claim he was born in Vidharba, Nagpur District nowadays part of the state of Maharashtra.

Modern researchers tend to think that there was a separate Ayurvedic writer called Nāgārjuna who wrote numerous treatises on Rasayana. Also, there is a later Tantric Buddhist author by the same name who may have been a scholar at Nālandā University and wrote on Buddhist tantra. The brand Nagarjuna Ayurveda from Kerala is nowadays’s highly popular in India, selling everything from balms to eye drops.

Add to the conundrum the fact that Nagarjuna is said to have written one of his collyrium recipes directly on a pillar in the old city of Pataliputra and we are in complete terra incognita, since Pataliputra, the capital city of several Indian dynasties thought to have existed in the vicinity of modern Patna, remains an archaeological puzzle to the day. In 2023, Bijoy Kumar Choudhary, Director of the Bihar Heritage Development Society, noted that “the archaeological remains, unearthed so far, are frankly to too scanty to showcase the rich heritage of Pataliputra.” (‘Unravelling Pataliputra’, Times of India, 23 April 2023)

The author was well-aware of these difficulties, since he added a Summary in English at the end of the book (pp 205 – 6):

“The plants and products prescribed in its formulas are well known elements of the general materia medica and their efficiency has been recognised since long not only in India and surrounding countries but in Ancient Europe also.

In fact this short book has been in use from Central Asia till Srilanka.

Later it has been translated into Tibetan, included in the Tanjur and has been commented upon by Bu-ston.

In Srilanka it is also represented by several mss. and has been printed several times together with a Sinhalese explanation. […]

Many of its formulas are quoted, sometimes with reference to Nagarjuna, and more often without any reference, in classical ayurvedic books like Vagbhata, Cakradatta etc…[…]

We had to examine the works ascribed to Nagarjuna or to several authors bearing his name.

The Chinese pilgrim and Buddhist philosopher Hiuan-tsang, in the Vllth century like Yi-tsing, describes the bodhisattva Nagarjima living 500 years before him (500 is a rough number but, in this case, fit to join the very time of Nagarjuna) as a great alchemist also, taking pills to prolong his life. He has no objection to admit he was both this alchemist and the philosopher of the sva- bhdvasunyatd. This is in accordance with the independant traditions which ascribe medical, chemical and even magical works, i.e. every kind of technical performances, to this Buddhist philosopher.

The examination of these medical and chemical works gives evidences of concordances between the teachings of the Uttaratantra of the Susrutasamhita (for which Nagarjuna is given as pratisamskart) and some data of Yogasataka and also with a theory on the absence of svabhdva in the substance (dravya) taught in the Rasavaisesikasutra also ascribed to Bhadantanagarjuna.

Finally there is a possibihty but no evidence to ascribe, with the majority of the ancient traditions, to Nagarjuna several medical works, including the Yogasataka which has got the greatest popularity. But, if we accept the information given by Yi-tsing, we have to admit that the compiler of the Yogasataka Uved in the Vlth century and belonged to a tradition of Nag^uniyas having its root in the milieu of Nagarjuna himself.”

While the attribution remains a question mark, further research will benefit from this translation, in particular the transliteration of so many Sanskrit names of plants and medical procedures. For instance, compare the index of Sanskrit names with the list of medicinal plants used in Cambodia drawn up by Pauline Dy Phon in her Dictionary.