La toponymie khmère / Khmer Toponymy

by Saveros Pou

How we can understand (or not) the names of ancient Khmer temples, settlements and landmarks in their modern forms.

Publication: Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 375, 377-451 (EFEO/JSTOR)

Published: 1967

Author: Saveros Pou

Pages: 76

Languages : French, Khmer

pdf 2.1 MB

While Sanskrit remained the medium for religious and official inscriptions and topographical designations, the Khmer language was rapidly developing as a specific linguistic system among the general population.

Based on a thorough epigraphic analysis, but also an intimate knowledge of modern Khmer idiomatisms, the study vividly shows how Sanskrit names mutated through Khmer pronunciation, or how the popular tradition often opted for renaming buildings and places according to its own worldview, with a predilection for references to geophysical characteristics or specific flora — and fauna in a lesser extent — encountered in the area.

While derivatives from Siamese, Vietnamese or Cham languages were not uncommon, in particular in the northernmost and southernmost regions, a genuine Khmer toponymy developed through the centuries. Sometimes, the phonetic similarity between Sanskrit words was played on, as with the words ´sri´ (glory) and ´stri´ (woman).

With some fascinating insights on the etymology of major toponyms (Angkor Wat, Bayon, Koh Ker…), the study also considers the instances where a famous, official site-naming simply disappeared to be substituted for a humbler, realistic designation. This is the case with Mahendraparvata, then the name of the mountain on top of which Jayavarman II established a temple proclaiming its ´god-king´authority against the Javanese invaders in the 9th century, a name still mentioned two centuries later in the Sdok Kak Thom inscription but never used in Khmer oral traditions, this hill being known as Phnom Kulen (Mountain of the Lychee Trees). ´Spontaneous naming´, as the philologists would say…

Note on ‘Bayon’ name: It has been said that the Bayon Temple was initially named Jayagiri (Mountain of Victory in Sanskrit), and that much later the French explorers called it ‘The Banyan Temple’, due to the number of banyan trees in the area; in the Khmer pronounciation, ‘Banyan’ became ‘Bayon’…

However, Saveros Pou offers two possible etymologies for the name: 1) Pa Yantra, “The High Yantra”, yantra being a circular building. 2) Vaijajanta, “Indra’s Palace”, mutated into Vejayantaratna in Khmer recitation, then Veyant, heard as Bayon in modern times…

- This study is only a part of the dissertation presented by the author for her doctorate in Linguistics and Epigraphy. Saveros Pou had started her researches under the guidance of distinguished Angkor scholars such as George Coedès, François Martini, Au Chhieng, Jean Filliozat and Louis Renou.

- In another publication, Saveros Pou furthered her research on the naming of Ancient Khmer monuments.

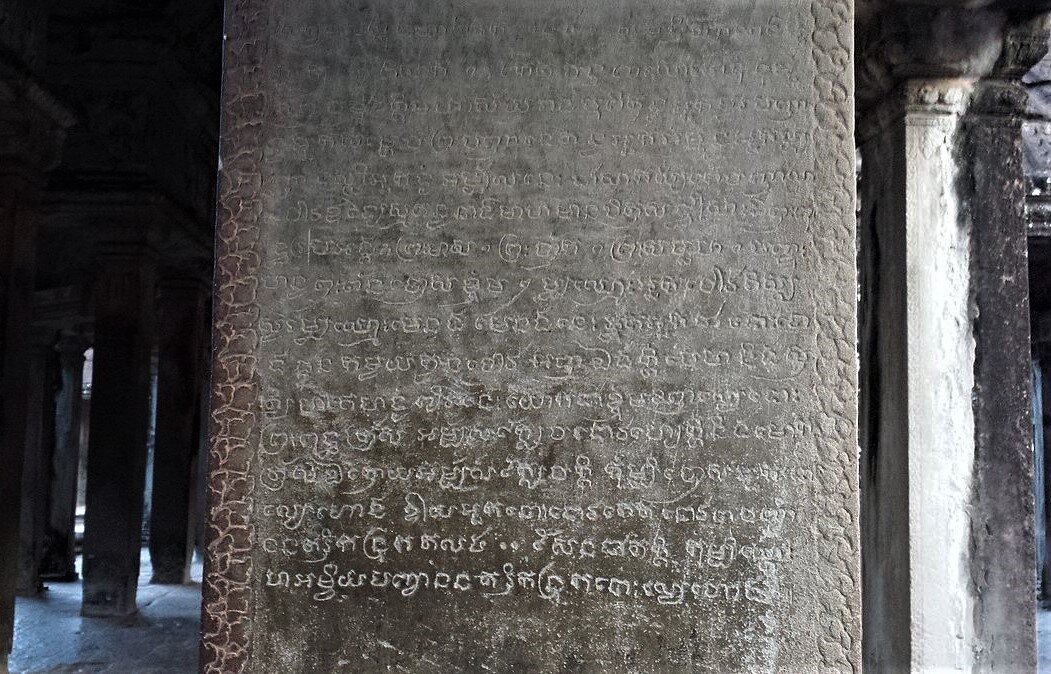

(Photo: Inscription within Angkor Wat)

Tags: toponymy, linguistics, Old Khmer, Sanskrit, epigraphy, Bayon

About the Author

Saveros Pou

Saveros Pou (Saveros Lewitz in the 1970s-1980s) ពៅ សាវរស (24 Aug. 1929, Phnom Penh- 25 May 2020, France) was a French linguist of Cambodian origin. A retired research director of the CNRS in Paris, a specialist of the Khmer language and civilization, she carried out extensive work of Khmer epigraphy, starting as a young researcher with teachers George Cœdès, Jean Filliozat, Louis Renou, Armand Minard, Anne-Marie Esnoul, André Bareau and the Cambodian intellectual living in Paris Au Chhieng.

Born in a respected and learned family — her uncle, Nhieuk Nou (1900−1982), was ‘okhnya mahamantri’ (Royal Palace secretary), her grandfather, Kae Nou កែ នូ (1864−1958), a judge and ‘pandit’ (sage), and her father Pou Chroeng ពៅ ច្រឹង a provincial governor and later on an officer at the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts -, she was raised after their mother’s premature death by her older sister, Pou Siphan ពៅ ស៊ីផាន់, and went to the Sutharot Girls School and Lycée Sisowath in Phnom Penh. She had wished to pursue higher studies in Philosophy abroad but her father first rejected the idea, and she was 21 when he gave her permission to go study in France, taking Linguistics, Literature and Anthropology at Sorbonne University, later adding degrees History, Geography, and Literature. (as per an interview conducted by Ham Chhayly ហម ឆាយលី on 27 June 27 1997).

Further studies under the guidance of Profs. Armand Minard (Sanskrit Grammar), Louis Renou (Philosophy and Sanskrit Literature), André Bareau (Buddhism and Pali) and Jean Filliozat (Culture and Civilization of Kalinga) led to her doctoral thesis “Reamker (Khmer version of the Ramayana, 16th – 17th century)” in 1978. Then, Saverous Pou went to England to deepen her knowledge of the Old Mon language (with Prof. G.H. Luce in Jersey) and Modern Mon with Prof. H.L. Shorto in London. At University of Hawai’i, she conducted additional research in linguistics.

Already a leading researcher in linguistics and social history of Cambodia, as well as a respected teacher for several generations of students, she exchanged ideas with Cambodian fellow researchers, had the opportunity to communicate with Khmer and Sanskrit pioneer researcher George Coedès and François Martini, and had a lasting influence on the younger generations of Khmerologists, from Ang Choulean to Grégory Mikaelian and others.

Her work in the field of etymology, specifically applied to old Khmer (from 6th to 14th centuries) was seminal, while her varied skills enabled her to tackle areas such as the very rich processes of derivation in Khmer, religion, codes of conduct, zoology and botany, culinary art, etc. This encyclopedic approach is reflected in her Dictionnaire vieux khmer-français-anglais.

‘Madame Pou’, as she was respectfully and affectionately referred to, is the author of more than 150 books and articles, published in several orientalist journals such as the Journal Asiatique and the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. Saveros Pou’s last book published before her passing away was Un dictionnaire du khmer-moyen (Phnom Penh, Buddhist Institute, Sāstrā Publishing House, 2017).

Publications

[sources: a) ADB Library Research; b) Grégory Mikaelian’s bibliography of Pou Saveros in Choix d’articles de Khmérologie. Selected Papers on Khmerology; c) Alida Ham’s bibliography in ជីវប្រវត្តិរបស់លោកស្រីបណ្ឌិត សាស្ត្រាចារ្យ ពៅ សាវរស (កម្រងសិក្សាខ្មែរចងក្រងដើម្បីរំឭកឧបការគុណ និងឧទ្ទិសជូនដល់លោកស្រីបណ្ឌិត‑សាស្រ្តចារ្យ) [A Biography of Dr. Pou Savros ( Khmer study series compiled in commemoration and dedication to Dr. Pou Savros)], compiled by ហម ឆាយលី Ham Chhayly, Phnom Penh, BE 2559 (2016), 49 p.]

- “La toponymie khmère”, BEFEO LIII, 2, 1967: 377 – 450.

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (I): Mots khmers considérés à tort comme d’origine savante”, Journal Asiatique (JA), 1967, 1: 117 – 31. [RVC1]

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (II): Mots sanskrits considérés comme khmers”, JA, 1967 2: 243 – 60. [RVC2]

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (III): Mots khmers considérés à tort comme d’origine siamoise”, JA, 1967 3 – 4: 285 – 304. [RVC3]

- “La dérivation en cambodgien moderne”, Revue de l’Ecole Nationale des Langues Orientales Vivantes (RENLOV), IV, 1967: 65 – 84.

- “L’accentuation syllabique en cambodgien”, Papers of the CIC Far Eastern Institute, Michigan 1968: 155 – 67.

- Lectures cambodgiennes (Reader), Paris, Maisonneuve, 1968, 110 p.

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (IV): Du mot ‘mourir’ dans le rājasabd”, JA, 1968: 211 – 7. [RVC4]

- “Note sur la dérivation par affixation en khmer moderne (cambodgien)”, RENLOV V, 1968: 117 – 27.

- “Quelques cas complexes de dérivation en cambodgien”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (JRAS), 1969: 39 – 48.

- “Note sur la translittération du cambodgien”, BEFEO LV, 1969: 163 – 9.

- “Notes ethnobotaniques sur quelques plantes en usage au Cambodge” [with J.E. Vidal, G. Martel], BEFEO LV, 1969: 171 – 232.

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (V) Les mots lanleń /lanlyin dans les inscriptions khmères”, JA, 1969: 157 – 65. [RVC5]

- [review] “Introduction to Cambodian par J.M. Jacob, London, OUP, 1968, in‑8°, 341 р.”, BSOAS XXXII, 3, 1969: 652 – 4.

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 2 et 3”, BEFEO LVII, 1970: 99 – 126. [IMANGK1]

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (VI): Les noms des points cardinaux en khmer”, JA, 1970: 131 – 41. [RVC6]

- [review] “The Khmer Language par Y.A. Gorgoniev, Moscou, Nauka, 1966, in-16, 134 р.”, Bulletin of the Society of Linguistics and Philology (BSLP), LXIV, 1970, 2: 232 – 5.

- [review] “Early Indo-Cambodian Contacts. Literary and Linguistic par K.K. Sarkar, Santiniketan, Viśvabharati, 1968, in‑8°, 76 p.”, BSLP LXV, 1970, 2: 34 – 6.

- “L’inscription de Phimeanakas (K.484). Étude linguistique”, BEFEO LVIII, 1971 : 91 – 103.

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 4, 5, 6 et 7”, BEFEO, LVIII, 1971: 105 – 23. [IMANGK2]

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (VII): Les doublets d’origine indienne”, JA, 1971:103 – 38. [RVC7]

- [review] “Cambodian System of Writing and Beginning Reader par F.E. Huffman, Yale Linguistic Series, Yale, 1970, in‑8°, 365 p.”, BSOAS XXXIV, 1973, 3: 649 – 50.

- “Deux cas de doublets en khmer”, in Langues et Techniques. Nature et Société, Hommage Haudricourt, Paris, Klincksieck, 1971, I: 149 – 56.

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 1, 8 et 9”, BEFEO LIX, 1972: 101 – 21. [IMANGK3]

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16a, 16b et 16c”, BEFEO LIX, 1972: 221 – 49. [IMANGK4]

- “Les inscriptions modernes d’Angkor Vat”, JA, 1972: 107 – 29.

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 et 25”, BEFEO LX, 1973: 163 – 203. [IMANGK5]

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 et 33”, BEFEO LX, 1973: 205 – 43. [IMANGK6]

- “Lexique des noms d’arbres et d’arbustes du Cambodge” [with B. Rollet], BEFEO LX, 1973: 117 – 62.

- “Some Chinese Loanwords in Khmer” [with P.N.Jenner], Journal of Oriental Studies (JOS), Hong Kong, XI, 1, 1973 : 1 – 90.

- “Kpuon Ābāh-bibah ou “Le Livre du mariage des Khmers””, BEFEO LX, 1973, p 243 – 328.

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien (VIII): Du vieux khmer au khmer moderne”, JA, 1974: 143 – 70. [RVC8]

- “ ‘Nuage’, ‘ciel’, ‘pluie’ et ‘grêle’ en khmer”, ASEMI V, 1, 1974: 107 – 11.

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 35, 37, et 39”, BEFEO LXI, 1974: 301 – 37. [IMANGK7]

- “The Word āc in Khmer. A Semantic Overview”, South-East Asian Linguistic Studies (SEALS), Canberra, 1974: 175 – 91.

- “Note sur la date du Poème d’Angkor Vat”, JA, 1975: 119 – 24.

- “Proto-Indonesian and Mon-Khmer”, [with P.N. Jenner), Asian Perspectives, XVII, 2, 1975:112 – 24.

- “Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor 34 et 38”, BEFEO LXII, 1975:283 – 353. [IMANGK8]

- “Les traits bouddhiques du Rāmakerti”, BEFEO LXII, 1975: 355 – 68.

- “Les Cpap’ ou ‘Codes de conduite’ khmers I. Cpāp’ Kerti kāl” [with P.N. Jenner], BEFEO LXII, 1975: 369 – 94. [CPAP1]

- “Notes de morphologie khmère”, ASEMI VI, 4, 1975: 63 – 9.

- “The Infix /-b/ in Khmer”, Austroasiatic Studies (AS), Honolulu, 1976, II: 741 – 60.

- “Note on Words for Male and Female in Old Khmer and Modern Khmer”, AS, 1976, II: 761 – 71.

- “Les Cpap’ ou ‘Codes de conduite’ khmers II. Cpap’ Prus” [with P.N. Jenner], BEFEO LXIII, 1976: 313 – 50. [CPAP2]

- «Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien IX”, JA, 1976:333 – 55. [RVC9]

- “Deux extraits du Rāmakerti”, Mon-Khmer Studies (MKS), VI, 1976: 217 – 45.

- [review] “Rioen Rāmakerti nai Tā Cak’. Histoire du Reamker, présenté par F. Bizot, Phnom Penh, EFEO, 1973”, Artibus Asiae (AAs), 1976, 38⁄4: 320 – 21.

- “Inscriptions en khmer moyen de Vat Athvéa (K. 261)”, BEFEO LXIV, 1977:151 – 66.

- “Les Cpap’ ou ‘Codes de conduite’ khmers III. Cpap’ Kūn cau” [with P.N. Jenner], BEFEO LXIV, 1977: 167 – 215. [CPAP3]

- [tr. and commentary] Rāmakerti (XVIè-XVIIè siècles), Paris, PEFEO vol. CX, 1977, 299 р.

- Etudes sur le Ramakerti (XVIè-XVIIè siècles), Paris, PEFEO vol. CXI, 1977, 201 р.

- “Inscription dite de Brai Svay ou ‘Bois des Manguiers’ de Sukhoday”, BEFEO LXV, 1978, 333 – 59.

- “Les Cpāp’ IV. Cpāp’ Rājaneti ou Cpap’ Brah Rājasambhār” [with P.N. Jenner), BEFEO LXV, 1978: 361 – 402. [CPAP4]

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien X. L’étymologie populaire”, JA, 1978: 153 – 77. [RVC10]

- Rāmakerti (XVIè-XVIIè siècles) (Textes khmer), Paris, PEFEO vol. CXVII, 1979, 339p.

- “Les Cpap’ V. Cpap’ Kram” [with P.N. Jenner], BEFEO LXVI, 1979: 129 – 60. [CPAP5]

- “Les pronoms personnels du khmer: origine et évolution”, SEALS 4, Canberra, 1979: 155 – 78.

- “Une description de la phrase en vieux-khmer”, MKS VIII, 1979: 139 – 69.

- “Subhāsit and Cpap’ in Khmer Literature”, in Ludwik Sternbach Felicitation Volume, J.P. Sinha ed., Akila Bharatyia Sanskrit Parishad, Lucknow, 1979, I: 331 – 48.

- “Some proper names in the Khmer Rāmakerti”, South East Asian Review (SEAR), 1980. V, 2: 19 – 29.

- “Inscriptions khmères K.144 et K.177”, BEFEO LXX, 1981: 101 – 20.

- “Inscriptions khmères K.39 et K.27”, BEFEO LXX, 1981: 121 – 33.

- “Les Cpāp’ ou ‘Codes de conduite’ khmers VI. Cpap’ Trineti” [with P.N. Jenner], BEFEO LXX, 1981: 135 – 93. [CPAP6]

- “La littérature didactique khmère : les Cpap”, JA, 1981: 454 – 66.

- “Liste d’ouvrages de Cpap’ ” [with K. Haksrea], JA, 1981 : 467 – 83.

- [review] “Seksa Khmer, Nº 1 – 2, Déc. 1980, Cedoreck, Paris, in‑8°, 241 р.”, JA, 1981: 516 – 8.

- “Etudes rāmakertiennes”, Seksa Khmer (SK), 3 – 4, 1981:89 – 110.

- “Inventaire des œuvres sur le Rāmāyaņa khmer (Rāmakerti)”, (en coll. avec Lan Sunnary, K. Haksrea), Seksa Khmer, 3 – 4, 1981: 111 – 26.

- A Lexicon of Khmer Morphology [with P.N. Jenner], Mon-Khmer Studies IX‑X, Honolulu, 1980 – 81, in‑8°, 524 p.

- “Les noms de plantes dans l’épigraphie vieux-khmère” [with M.A. Martin], ASEMI XII, 1 – 2, 1981: 3 – 73.

- “Notes historico-sémantiques khmères “, ASEMI XII, 1 – 2, 1981: 111 – 24.

- Rāmakerti II (Deuxième version du Rāmāyana khmer), Paris, PEFEO vol. CXXXII, 1982, 305 p.

- “Jean Filliozat: le guru que j’ai connu, SK 5, 1982: 5 – 9.

- “Du sanskrit kīrti au khmer kerti : Une tradition littéraire du Cambodge”, SK 5, 1982: 33 – 54.

- “A propos du nom d’une plante jir”, SK 5, 1982:55 – 60.

- “Dharma and trivarga in the Khmer Language”,Dr. Babu Ram Saksena Felicitation Volume, XI-XV, J.P. Sinha ed., Lucknow, 1983: 289 – 97.

- “Rāmakertian Studies”, Asian Variations in Ramayana, Srinivasa Iyengar ed., Delhi, Sahitya Akademi, 1983: 252 – 62.

- “Recherches sur le vocabulaire cambodgien XI. Des verbes ‘parler’ en khmer, JA, 1983, 3 – 4: 345 – 62. [RVC11]

- “A propos de ramās bhloen ou ‘rhinocéros du Feu’ », SK 6, 1983: 3 – 9.

- Nouvelles préfaces (2 x 10p. KH+FR) aux Inscriptions modernes d’Angkor, Paris, Réimpression Cedoreck, 1984. [IMANGK9]

- “Sarasvati dans la culture khmère”, Bulletin d’Etudes Indiennes (BEI), 2, 1984: 207 – 12.

- “Lexicographie vieux-khmère, SK 7, 1984, 67 – 175, Pl.

- [review] “Khmer Ceramics, Singapore, 1981”, SK 7, 1984: 255 – 7.

- ‘Prakrit loan-words in Old Khmer’, Rtam 16 – 18, 1984 – 1986: 259 – 67.

- [review] “Mahāvessantarajātak (Nuk Thaem, éd.), Paris, Réimpression Cedoreck & ABK, 1982, in‑8°, 480 p.”, SK 7, 1984: 257 – 62.

- [review] “Khmer = Kham par Chatra Prem Reudi, République Khmère, Phnompenh, 1974”, SK 7, 1984:262 – 5.

- Notes sur les coutumes et croyances superstitieuses des Cambodgiens par Etienne Aymonier (Commentaire et présentation), Paris, Cedoreck, 1984, 116 p.

- “Old Khmer Lexicology”, Indus Valley to Mekong Delta. Explorations in Epigraphy, Madras, New Era Publications, 1985: 287 – 99.

- “Rāmakerti — The Khmer (or Cambodian) Rāmāyaņa”, Sanskrit and World Culture, SCHR. OR., 18, Berlin, 1986: 203 – 11.

- “Indic Loanwords in Khmer other than Sanskrit”, Kambodschanische Kultur (KK) 1, Berlin, 1986: 48 – 55.

- “Vocabulaire khmer relatif aux éléphants”, JA, CCLXXIV, 3 – 4, 1986: 311 – 402.

- “Sarasvati dans la culture khmère”, BEI 4, 1986: 321 – 39.

- [review] “International Seminar on Rāmāyaņa. Traditions and National Cultures in Asia 2 – 6 Oct. 1986, Lucknow”, BEI 4, 1986: 51 – 55.

- “Etudes sur le Rāmāyana en Asie (1980−1986)”, JA, 1987, 1 – 2: 193 – 201.

- “Old Khmer and Siamese”, KK 2, Berlin, 1988: 37 – 48.

- កម្រងច្បាប់ — Guirlande de Cpap’, Paris, Cedoreck, 1988, 2 vols. 638 p.

- [review] “Reamker (Ramakerti), the Cambodian version of Ramayana, Translated by J.M. Jacob, London, The Royal Asiatic Society, Oriental Fund, New Series (XLV), 1986, in‑8°, 320 p.”, KK 2, 1988 : 72 – 6.

- “Notes on Brahmanic Gods in Theravādin Cambodia”, Indologica Taurinensia, XIV, Colette Caillat Felicitation Volume, 1987 – 88: 339 – 51.

- “Sanskrit Loanwords in Old Khmer: Some morphological Observations”, Dialectes dans les littératures indo-aryennes, Pub. ICI, 55, Paris, Collège de France & ICI, 1989: 569 – 78.

- “Portrait of Rama in Cambodian (Khmer) Tradition”, Rāmāyaņa Traditions and National Cultures in Asia, D.P. Sinha & S. Sahai eds., Lucknow, Directorate of Cultural Affairs (Uttar Pradesh), 1989: 1 – 7.

- Nouvelles Inscriptions du Cambodge, Paris, PEFEO CTDI-XVII, vol. I, 1989, 155 p.

- “Le khmer et ses locuteurs”, Language Reform. History and Future, I. Fodor & C. Hagège, eds., Hamburg, Helmut Buske Verlag, vol. V, 1990: 239 – 52.

- “Regard sur les études littéraires khmères”, SK 10 – 13, 1987 – 90: 39 – 58.

- “Vocabulaire khmer relatif au surnaturel” [with Ang Choulean], Seksa Khmer 10 – 13, 1990 – 90: 59 – 129.

- C.R. de Khmer Buddhism and Politics from 1954 to 1984 par Yang Sam, Khmer Studies Institute Inc., Newington (U.S.A.), 1987, petit in‑8°, 97 p., SK10 – 13, 1990: 134 – 36.

- “Sanskrit, Pali and Khmero-Pāli in Cambodia”, Panels of the VIIth World Sanskrit Conference, vol. VII, Sanskrit outside India, J.G. de Casparis ed., Leiden, Brill, 1991: 13 – 28.

- “Les dérivés désidératifs en khmer, Austroasiatic Languages, Essays in honour of H.L. Shorto, London, SOAS, 1991: 183 – 91.

- “Les noms des monuments khmers”, BEFEO LXXVIII, 1991: 203 – 24, Pl.

- “Conférence Internationale sur le Rāmāyaņa de Vālmīki, Turin 1992”, BEI 9, 1991: 235 – 7.

- Lectures cambodgiennes — A Cambodian Reader, Paris, Cedoreck, 1991, 109p.

- “Notes historico-sémantiques khmères”, Asie du Sud-Est et Monde Insulindien (ASEMI) XII, 1 – 2, 1991 : 111 – 124.

- [review] “Dialectes dans les littératures indo-aryennes, Paris, Collège de France & ICI, 1989, 578 р.”, BEFEO LXXVIII, 1991: 337 – 9.

- [review] “Ramayana Traditions and National Cultures in Asia, Sinha, D.P. & Sahai, S., ed., Lucknow, 1989, 22×28, 222 p., illustr.”, BEFEO LXXVIII, 1991: 339 – 42.

- [review] “Circles of Kings. Political Dynamics in Early Continental Southeast Asia, par Renée Hagesteijn, Dordrecht-Holland, Providence‑U.S.A., 1989, ib‑8°, 175 р.”, BEFEO LXXVIII, 1991: 347 – 9.

- [review] “A Glossarial Index of the Sukhothai Inscriptions par Ishii, Y, & Al., Bangkok, Amarin Publication, 1989, 15 x 26, 254 p.”, BEFEO LXXVIII, 1991: 349 – 51.

- Dictionaire vieux khmer-français-anglais — An Old Khmer-French-English Dictionary — វចនានុក្រមខ្មែរចាស់-បារាំង‑អង្លេស, Paris, Cedoreck, 1992, 555 p. ISBN 2−86731−023−7; 2d augmented edition: Paris, L’Harmattan, 2004, 732 p.

- “Khmer cuisine vocabulary”, KK 4, 1992:50 – 60.

- “Des mots khmers désignant ‘les documents écrits’ ”, MKS XX, Thompson Festschrift, 1992: 11 – 17.

- “From Old Khmer Epigraphy to popular Tradition: A study of the names of Cambodian monuments”, Southeast Asian Archaeology 1990, Proceedings of the Third Conference of the EASEAA, Ian Glover ed., Centre for South-East Asian Studies, University of Hull, 1992: 7 – 24.

- “Indigenization of Rāmāyana in Cambodia”, Asian Folklore Studies (AFS) vol. LI‑1, 1992: 89 – 102.

- [review] “Rāmāyaņa and Rāmāyaņas, ed. Monika Thiel-Horstmann, Wiesbaden, Otto Harrassowitz, 1991, 259 p.”, AFS LI‑2, 1992: 376 – 8.

- “From Old Khmer Epigraphy to Popular Tradition: A study of the names of Cambodian monuments”, Southeast Asian Archaeology, Proceedings of the Third Conference of the EASEAA, Ian Glover ed., Center for South-East Asian Studies, University of Hull, 1992: 7 – 24.

- “Īsūr-īśvara, ou Śiva, au Cambodge”, Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica (OLP), 24, 1993: 143 – 77.

- “From Valmiki to Theravāda Buddhism: The example of the Khmer classical Rāmakerti”, Indologica Taurinensia, XIX-XX, Proceedings of the Ninth International Rāmāyana Conference (Torino, April 13 th-17th, 1992), 1993 – 4:267 – 84.

- “Vişnu-Nārāy au Cambodge”, OLP 25, 1994: 175 – 95.

- “Ancient Cambodia’s epigraphy: the concept of merit-making and merit-offering”, in Pierre-Yves Manguin ed., Southeast Asian Archaeology 1994, part II.

- “L’offrande des mérites dans la tradition khmère, JA, CCLXXXII, 2, 1994:391 – 408.

- “Indra et Brahma au Cambodge”, OLP, 26, 1995: 141 – 61.

- “Introduction à l’étude du vieux khmer” [with S. Vogel], Cahiers d’études franco-cambodgiennes (CEFC), 4, Jan. 1995: 1 – 41.

- “Mahori khmer: étude culturelle”, CEFC, 5, Jul. 1995: 1 – 23.

- Nouvelles inscriptions du Cambodge, II, EFEO, Paris, 192 p.

- “Les termes grammaticaux du vieux khmer (6è-14è siècle)”, BEFEO 83, 1996: 21 – 34.

- “L’épigraphie khmère”, Angkor et dix siècles d’art khmer, Paris, RMN, 1997: 53 – 61.

- “Khmer Epigraphy”, Sculpture of Angkor and Ancient Cambodia: Millenium of Glory, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1997:53 – 61.

- “Les termes grammaticaux du vieux khmer (6è-14è siècles)”, Péninsule 34 (1), 1996: 95 – 117.

- “Music and Dance in Ancient Cambodia as Evidenced by Old Khmer Epigraphy”, East and West, IsIAO, Vol. 47, 1 – 4, Dec. 1997: 229 – 48.

- “Ancient Cambodia’s Epigraphy: a Socio-linguistic Look”, Southeast Asian Archaeology 1996, University of Hull, 1998: 123 – 34.

- “Ancient Cambodia’s Epigraphy: the Concept of Merit-making and Merit-offering, Southeast Asian Archaeology 1994, Univeersity of Hull, 1998: 97 – 102.

- “Dieux et rois dans la pensée khmère ancienne”, JA, 286 – 2, 1998: 653 – 69.

- “Praśasta Kamvujā ou Epigraphie du Cambodge”, OLP, 29, 1998: 113 – 26.

- “What is Khmerology?”, Khmer, 1 – 16, transl. by Vong Sotheara, English, 1 – 10, Phnom Penh, Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, 2000.

- Nouvelles inscriptions du Cambodge, II & III, EFEO, 288 p.

- “Āśrama dans l’ancien Cambodge”, JA, 290 – 1, 2002: 315 – 339.

- “The concept of avatara in the Ramayana Tradition of Cambodia”, OLP.

- “Nouveau regard sur Śiva-īśvara au Cambodge”, BEFEO 89, 2002: 145 – 82.

- Choix d’articles de Khmérologie. Selected Papers on Khmerology [presented by Grégory Mikaelian], Phnom Penh, Reyum, 2003, 503 p.

- “The concept of avatara in the Ramayana Tradition of Cambodia”, OLP 31, 2005:123 – 35.

- “Les fleurs dans la culture khmère”, JA 293 – 1, 2005: 45 – 98.

- “Comment nommer les espèces végétales nouvelles: Le Lexique khmer moyen”, JA 294 – 2, 2006: 373 – 407.

- Ramakerti I: ‘La Gloire de Rama’, drame épique médiéval du Cambodge [with Grégory Mikaelian], Paris, L’Harmattan, 2007.

- “Emprunts lexicaux khmer-moyens au monde indo-persan”, JA 296 – 1,2008:141 – 156.

- Nouvelles inscriptions du Cambodge vol IV, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2011.

- សទ្ទានុក្រម សំស្រ្កឹតខ្មែរ‑បារាំង — Lexique de Sanskrit-Khmer-Français (Sanskrit utilisé au Cambodge), Editions Angkor, Phnom Penh, 2013.

- [awaiting publication] “Satya, śapatha and sāksī in Cambodia’s Tradition”, Proceedings of the 13th World Sanskrit, Edinburgh Conference, July 2006.

- [awaiting publication] “Un texte de Satyapranīdhān du 17e siècle cambodgien” [with Grégory Mikaelian].

- Un dictionnaire du khmer-moyen, Phnom Penh, Buddhist Institute, Sāstrā Publishing House, 2017, 325 p.

Conference Communications

- International seminar on Rāmāyaņa traditions and national culture In Asia, Lucknow (India), 2 – 6 Oct.1986.

- Conférence Internationale sur le Rāmāyaņa de Valmīki, Torino (Italy), 1992 [BEI 9, 1991: 235 – 7].

- La langue khmère, la linguistique et le khmer, manuel de grammaire khmère: perspective de travail, emprunts indo-aryens, lexique et datationm. La littérature khmère: thème et genres littéraires, état des études littéraires khmères et littérature khmère, Phnom Penh Royal University with Alliance française and Cercle de linguistique franco-khmere, 9 – 23 February 1993.

- Ancient Cambodia’s Epigraphy: a Socio-Linguistic Look, European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, 6th International Con-ference, Leiden (the Netherlands), 02 – 06 September 1996.

- Phnom Penh Buddhist Institute: research at the invitation of Dr. Hema, UN Cultural Section representative in Cambodia, 24 Dec 1998- 19 Jan. 1999.

- The Hermitage (Asrama) in Ancient Cambodia as Evidenced by Epigraphy, Albert-Ludwings Universität Freibourg, Orientalisches Seminar, Indologia, 11 Nov. 1999.

- The Victoria and Albert Museum and the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, Proceedings of the 10th EurASEAA Conference, London, 14 – 17 Sept. 2004.

- Satya, Sapatha and Šaksi in Cambodia’s Tradition, Proceedings of the 13th World Sanskrit Conference, Edingburgh, (Scotland, UK), 10 – 14 July 2006.

- Kalpana in Ancient Cambodia, Proceeding of the 10th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, London, 2008.