Narrative of an Overland Journey from Kampot to the Royal Residence ['Cambodia in 1851']

by Ludvig Verner Helms

A rare account of the country of Cambodia and the King's Court at Oudong in 1851, eight years before Henri Mouhot's famous exploration.

- Publication

- Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, ed. J.R. Logan, vol 5, Singapore, 1851, pp 435-8 [Kraus Reprint, Nendeln, 1970]

- Published

- 1851

- Author

- Ludvig Verner Helms

- Pages

- 4

- Language

- English

pdf 249.3 KB

CAMBODIA IN 1851. Journal Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, vol 5 , pp 435 – 8

I. Notices of the Port of Kampot, with Directions for the Eastern Channel, By Captain G[eorge] D. Bonnyman [1]. [published separately here]

II. Narrative of an Overland Journey from Kampot to the Royal Residence, By L. V. Helms, Esq.

(In the early part of February last, the brig “Pantaloon” was dispatched on a trading voyage to Kampot by a mercantile firm here, the Messre Almeida and Sons [2], and returned with a cargo of Cambodian produce in the month of June. During the stay of the “Pantaloon” at Kampot, Captain Bonnyman made a plan of the anchorage and the Eastern Channel on a large scale, from which the map which accompanies these notices has been reduced, and which beais upon the face of it evidence of having been constructed with great care and accuracy. In the mean time, Mr Helms, the super cago, visited the Royal Residence, accompanied by Mr Monteiro, (the envoy of the king of Cambodia, who furnished the principal materials from which the map in the May number of this journal was compiled) who returned to Kampot in the“Pantaloon”. Mr Helms drew up a lively narrative of his overland journey, which appeared in the Singapore Free Press of the 20th June, and which is republished here as a useful supplement

to Captain Bonnyman’s hydrographical notices.)

II OVERLAND JOURNEY FROM KAMPOT TO THE ROYAL RESIDENCE, by L.V. Helms

To the Editor of the Singapore Free Press

[note: this account was adapted in Helm’s 1888 book, Pioneering in the Far East.]

Observing how willingly you have received for publication any information regarding Camboja, I beg to offer you some observations on that country made during a late visit to it. As it has been so seldom visited by Europeans, it is very imperfectly known, though it may well be considered an object deserving attention, equally on account of its geographical position, its valuable productions, and the friendly disposition of the inhabitants towards Europeans. For these reasons I have thought it worth while to contribute my share in drawing the attention of your readers towards a place which may one day prove to be the key that shall open an extensive held for European enterprise.

In an article on Camboja which appeared in your paper a few months ago, it was stated how that country from its former magnitude and power, had, pressed by its two powerful neighbours Siam and Cochin China, gradually sunk down to its present insignificant and dependent state, — that of their former extensive sea-coast Kampot is now the only harbour left the Cambojans for exportation of their productions, a place whence Cambojan produce never can be exported to any extent, it being situated in the extreme west, which is the thinnest populated and least cultivated part of the country, with no means for inland navigation, the river upon which it is built being navigable for small craft and for a short distance only, and its couise being northward and disappearing in the mountains. Besides, a bar lying in the mouth of the river, makes it difficult even for cargo boats to enter, and the whole distance

which cargo has to be carried to the shipping is about 9 or 10 miles. The water being shallow no closer anchorage has as yet been found for vessels drawing 10 feet and upwards. For these reasons it will be seen that Kampot is entirely insufficient as an outlet for Cambojan produce, while Cancao, Basak and other Cambojan ports, commanding the large and navigable rivers which traverse this country through its most fertile and populous parts, penetrating into the very heart of Asia, are now in the hands of the CochinChinese, who have thus got the trade of Camboja in their own hands. The greater and more valuable part of this trade is carried on by way of Saigon and the jealousy of the Cochin-Chinese permits access to this port to none but Chinese. Even on the canal of Cancao, which only a few years ago belonged to Camboja, the king of that country is not permitted to export any goods. This Prince formerly resided at a place laid down on most maps under the name of Camboja, at a point where 4 branches of the Camboja river unite, but when his palace was burnt down by the Cochin-Chinese a few years ago, he retired about 10 miles more to the westward to a place called Udong, his present residence, and situated about 200 miles in a northern direction from Kampot.

Having on my arrival at Kampot made know to the Governor of that place my desire to visit Udong for trading purposes, he placed a number of carts and 2 elephants at the disposal of me and my travelling companions, amongst whom was a Mr Monteiro [3], formerly mentioned in your paper as having visited Singapore on a mission from the King, and who was now returning from this mission in our company. Our small caravan left Kampot on the 3rd March, travelling in a north-easterly direction in good cheer, but not with great speed, making only about 20 miles in 24 hours.

The features of the country we traversed were altogether level, consisting of large plains overgrown with forest, in which the teak, gum dammar, wild mango, and different kinds of palm trees frequently occurred. It being the dry season water was very scarce, and that which was to be found of a bad description. There being no rivers or lakes, travellers and the few inhabitants who live scattered in these forests, depend for water on the small ponds which receive their supply during the rainy season but often dry up during the summer. The appearance of the country in general indicates a rich soil, and although this was the dry season, plants and trees looked healthy and fresh. Though human habitations were seldom seen yet the country had a cheerful appearance, the underwood in most cases being burnt away, leaving the eye at liberty to penetrate far under its deep green foliage, and herds of deer and wild buffaloes being often seen grazing on the rich plains, A roof was seldom seen on our road, and we consequently spent our nights in the open forest, fortifying ourselves the best way we could, and by keeping up a brisk fire round our camp, we secured ourselves against any unwished for visitants. It cannot be said that we

encountered any adventures of a serious or alarming kind, though of course it was often stated when morning came that various suspicious sounds, sundry paire of fierce eyes &c. &c. had been heard and seen in our neighbourhood, and when ou one occasion a buffalo ran away, one of the party had certainly heard a howl like that of a tiger, and the noise made by its bolting away between the carts.

On the fifth day we arrived at a small village stated by Monteiro as being within the boundary of his government,

and where we had to get other conveyances. This however was not an easy matter, only three were to be had, the people assuring us that they had no more carts. Monteiro however seemed to be better informed, and used a very effective method for procuring carts. He ordered several of these men to be put in the stocks, and we had presently the gratification to find that they remembered where carts were to be got. Here too we were informed that some elephants belonging to the King had passed the previous day. His Majesty having been informed that we

were on our way to his place, had sent them to meet us, and bring us forward more speedily, but as they had taken a different road they missed us.

On the tenth day we reached Udong [4] in the evening exceedingly exhausted, having ti-avelled ten days successively in carts, which by no means rolled on springs, but at every trifling impediment to the wheels sent the unfortunate traveller flying. Seeing these miserable carts one would think it impossible that they could travel such a distance, but in their weakness consists their strength; being patched and tied together they are perfectly elastic and give way to anything opposed to them. When they do break down ‑which happens about twice in twenty four hours -, the driver far from being distressed by the accident, coolly takes out a piece of cord or rattan, ties the wheel together and away it goes again.

Having arrived at Udong Mr Monteiro offered us his house, where his hospitality soon gave relief to our fatigued bodies. Next day a person from the King informed me that he could net see us that day, it being a holiday, but would do so on the succeeding one, in the building where he gives audience, charging me at the same time to state in plain words that the object of this visit was trade, adding that a report that an English vessel had arrived at Kampot had reached Siam and Cochin-China, and that emissaries had arrived from these countries to enquire what might be its object. At the same time he sent an interpreter conversant with the Malay and Cambojan languages. Agreeable to this arrangement we were next day brought to the house of the Prime Minister, who received us in a very friendly manner, and after having offered us refreshments put some questions regarding the object of our voyage and

enquired what presents had been brought for the Rajah. Being satisfied on these points, he caused us to be conveyed to another building, where he presently appeared himself together with a number of other functionaries, amounting to more than thirty. Their functions were such as those of chief judge, minister of war, collector of customs, master of the king’s elephants, chief of the Malays, &c. &c. People who have petitions to present or complaints to make, bring them here where they are given to the different persons to whose departments they relate. Everything arranged and the time when the king gives audience being arrived, these functionaries, dressed in red robes ornamented with gold lace, took their way to the king’s palace asking us to follow.

It may here be proper to say a word or two about the appearance of Udong and the king’s residence. It has indeed little in its appearance which indicates it to be the residence of a prince who formerly ranked amongst the most powerful rulers of the east. It has an appearance of poverty and neglect, which, considering what Camboja has been, tell more plainly than words can do what these people have suffered during the last 15 or 20 years of almost uninterrupted ruthless incursions from the Siamese and Cochin-Chinese. Their houses or rather huts are almost without exception built of bambu and attap [5]. These poor people have 80 often seen their homes consumed by the flames of the enemies torch, that they have no longer any confidence to erect permanent buildings. Even their cocoanut and other fruit trees have been destroyed by their merciless enemies the Cochin Chinese. The population of Udong may amount to about 10,000 souls, principally Cambojans, with a few Siamese, Cochin-Chinese and Chinese. In about the centre of the town is a spacious square surrounded by a wall, with a gate on each side defended by a kind of tower. Within this the king’s palace is situated, surrounded by another wall, not however like the first one

calculated for defence. The buildings occupied by the king are without any architectural ornaments or spires and principally constructed of wood. We were introduced into a large square building, the audience hall of the king, and in the upper end of which, raised about 1 1/2 feet, was placed a gilt chair or throne. The persons assembled laid themselves prostrate on the ground, awaiting in this position the appearance of the King, which presently happened.

He is a man of about 56 years of age, something below middle size, and rather stout, his face is strongly marked by small pox, but with an expression of mildness and benevolence in features and demeanour which seems to be his natural disposition. He welcomed us with a friendly nod of the head, and seemed to be much pleased to see us. He enquired very particularly as to our names, country, length of voyage and motives for coming there. Having conversed for some time, he said that he had ordered a house to be prepared for our reception, and then ordered the different reports and other communications to be read. This was done, and after the perusal of each, the King

generally addressed some of the functionaries assembled, to ask their opinion on the subject, and the proceedings were not seldom interrupted by a roar of laughter, although, as I was told, some of the reports received were not of the most pleasing kind, conveying information of the outbreak of an insurrection in the northern part of the country.

We were twice invited to the Rajah’s private apartments, which though they displayed nothing magnificent, but were on the contrary rather ordinary looking, still had an air of comfort, altogether so different from what appeared to be customary, and seemed to shew an attempt to imitate European customs, that it may deserve a word of description. This place was separated from the Court of the Audience-hall by a wall, a door in which led into a flower garden, evidently cultivated with much care, and in which a flagstaff was placed, from whence was flying a flag precisely similar to that of my own dear country, Denmark. In the back ground of this garden was a long low wooden building,

the roof of which, on the side fronting the garden, rested on pillars of wood. The whole building comprised only’ one room, screened off in the middle by Chinese screens, on the walls were hung several engravings and looking-glasses, but no arms of any kind, and it contained several pieces of furniture, such as tables and chairs. The latter however may have been procured for our accommodation, as natives and Chinese are always required to lay themselves prostrate in the King’s presence. From us however he demanded no other obeisance than what would have been offered to a person of high rank in any other country, but received us cordially and frankly. He made minute enquiries about everything relating to European manufactures and arts, &c. &c. and his questions proved him to be much more conversant with these subjects than might have been mooted. He enquired with much interest into the superiority of different branches of English and French industry, and other matters relating to these two nations. It was evident that having acquired much of his information from French Missionaries he now took this opportunity for comparing notes. During the course of conversation he showed how desirous he is of having closer intercourse with Europeans. He expressed his desire of seeing European vessels now as formerly come up the

river, explaining the advantage of this, but on my enquiry whether in such case he could give a pass which would be sufficient protection against the Cochin-Chinese, he said that a pass from him would not be respected by the Cochin-Chinese, and that an additional number of guns on board would be far better protection.

I had a short time afterwards an opportunity of seeing how entirely he is at the mercy of the Cochin-Chinese. He had sold to me a quantity of produce which he was to send to Kampot by way of the Cancao canal, a distance which may be made in 10 or 12 days. The boats had already reached half that distance, when the Cochin-Chinese, hearing that the goods in question were destined for an English vessel, prohibited their further progress and compelled the boats to return. This will perhaps better than aught else shew the position in which the King of Camboja at present is placed, and it is to be highly regretted that this Prince, though still ruler of an extensive and productive country,

and desirous of forming fiiendly and commercial relations with Europeans, should be prevented from doing so by jealous neighbours, closing for him those rivers which are the natural high-road of his country and by right belong and have for centuries belonged to him, and which are the only means by which the produce of his country can be exported, unless it is to pass through the hands of the Cochin-Chinese.

We returned from our visit to the King of Camboja grateful for the kindness and hospitality with which he and his people had received us, the more so as it is a rare occurrence that Princes in this part of Asia are friendly or even

civil towards Europeans. May he find a powerful friend who may assist him to recover his just rights, and in so doing give him the power of opening to European commerce a new and vast field.

[1] George D. Bonnyman was then Captain of the brig Pantaloon.

[2] Jose d’Almeida Carvalho E. Silva (Dr) (27 November 1784, St Pedro do Sul, Portugal — 17 October 1850, Singapore) was a former Portuguese naval surgeon who came to Singapore in 1825 to set up a dispensary, and later became one of Singapore’s leading merchants. On letters of trade, he appeared as ‘Almeida’ or ‘Silva Joseph’, and from 1837 “Jose d’Almeida & Sons” when two of his numerous sons — he had 19 or 20 children with different wives, Joaquim and Jose, started work at the firm. [see ONG Eng Chuan, National Library Board blog entry, 2019]

[3] Constantin de Monteiro, uncle or cousin of Bernard Col de Monteiro, who was to become Prime Minister of Cambodia. Bernardo Ros de Monteiro, Col de Monteiro’s father and Constantin’s brother or cousin, had taken part in Pere Bouillevaux’s expedition to Angkor in 1850. Constantin became a close advisor to King Norodom and one of his daughters, Néak Moneang Phayâm (1850−1915), married the king, their daughter, Princess Malika (1872−1951) becoming the spouse of Prince Aruna Yukhantor (1860−1934).

[4] 10 days of travel on foot, on elephants, by cart and boat from Kampot to Oudong: travelers had to go round Elephant Range (Bokor Hill) from the southwest to head northward to the Royal Residence, the same itinerary taken by Auguste Pavie years later, in 1876. King Ang Duong had ordered that same year, 1851, that a more direct road be built between Oudong and Kampot.

[5] Malayo-Javanese term for thatch made from the fronds of Nipa palm trees.

Tags: 1850s, King Ang Duong, British travelers, Danish travelers, geography

About the Author

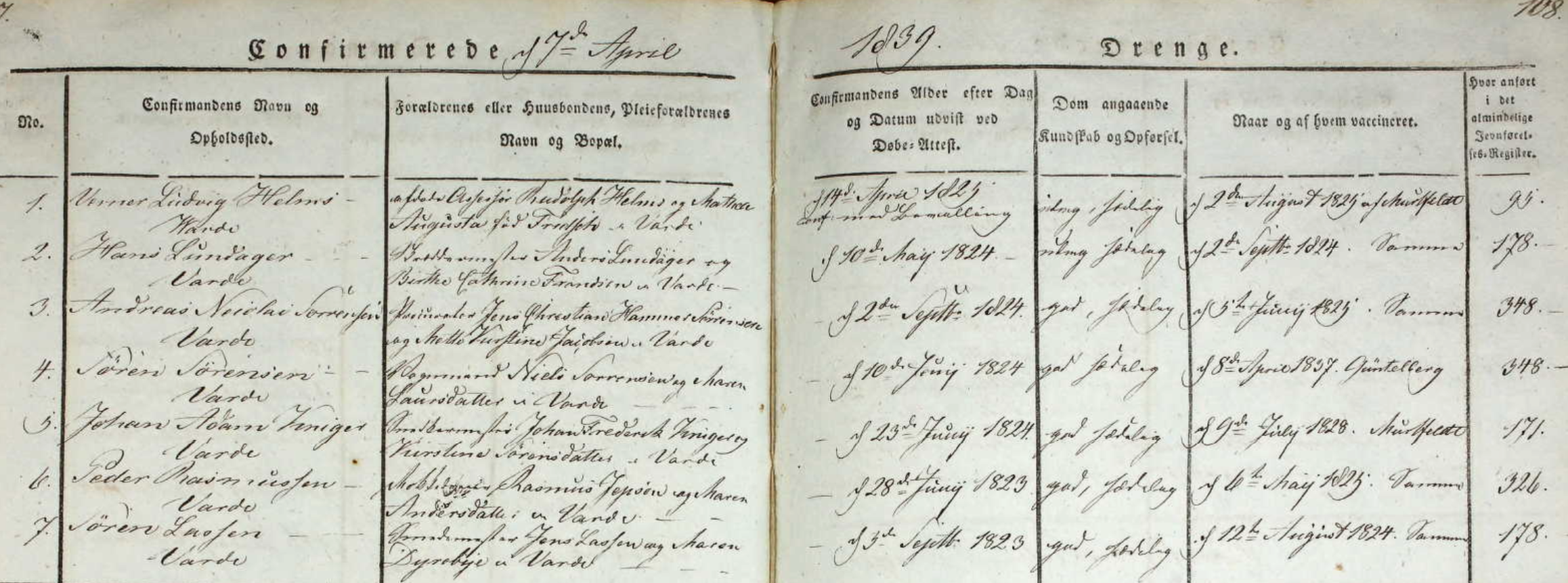

Ludvig Verner Helms

Ludvig Verner Helms [Verner Ludvig on his birth certificate] (14 April 1825, Varde, Denmark – 26 July 1918, Hampstead, England) was a merchant, explorer and author of Danish ascent who was active in trade across Southeast Asia during for twenty-eight years as a trader associated with British interests — MacEwen & Co, R.& J. Henderson- in Singapor, and the first manager of the Borneo Company Limited (BCL) — registered in London by the first Rajah of Sarawak James Brooke as a mining company in London in 1856, then adding banking activities — in Sarawak from 1852. He visited the court of King Ang Duong and Cambodia, as well as the one of King Rama IV (Mongkut) in Bangkok, between February and June 1851.

“In September 1846 I left my native land, Denmark, to seek my fortunes in the world,” Helms’ opening sentence of his sole published book, Pioneering in the Far East, aptly describes the life of an indefatigable traveler who thrice crossed the Pacific Ocean, sometimes at the helm of the ship carrying him — like in 1849, when the crew refused to come back onboard in San Francisco port during his first visit to California -, and went as far as the White Sea [Белое море, Arkhangelsk, Russia] and Lapland [Finland].

His ancestor, Adam Helms, was the son of a merchant from Lübeck, the Hanseatic League city where Martin Luther launched his Reformation movement. His father Rudolph, the first apotheker (pharmacist) in the small town of Varde on the North Sea died when Ludvig was eigth years of age, and through his elder siblings he heard of the adventures of Danish merchant Mads Lange, whose daughter Cecilie was to become Sultana of Johore. In a souvenir book he later wrote for his grandchildren, he wrote:

Young, full of health and spirits, and with all the world before me, I built a hundred castles in the air… There was indeed a great fascination about Bali, no one that I had ever come across had been to it, even in books there was little to be learnt concerning it, but that little was of a nature to excite one’s curiosity. It was described as a small paradise… inhabited by an interesting, handsome race of natives who were independent, proud, and unwilling to admit Europeans among them. One stranger only, this countryman of my own, had managed to establish himself there… Romantic stories of his doings, his influence and his wealth, were afloat. These had captivated my imagination, and… I had determined to visit him and offer him my services. [1]

Starting with Bali, where he was active in 1847 – 1849, Helms traveled around the world, visiting California, Cambodia, Siam (Thailand), Sarawak (nowadays a State of Malaysia) — where he built his house, called Anaberg, while also residing in Kuching during the local insurrection -, Brunei, Japan, Australia, the White Sea. At ease with grandees, he knew to stay self-possessed and critical. While visiting the powerful head of the Mormon Church in Salt Lake City, Utah, Brigham Young, the polygamist spiritual leader attempted to flatter him by praising Scandinavian women, but he wrote in his notes: “I must say that the appearance of those seen [there] did not seem to indicate that the peculiar institution had brought them much happiness.”

In 1858, during one of his trips back to England, he married Ann Amelia Bruce, then 20, one of the six children of Thomas Bruce, a Scottish businessman, and Louisa, a couple of Nonconformists who lived in Suffolk, whose eldest sister was in living in China with her missionary husband. They had six children.

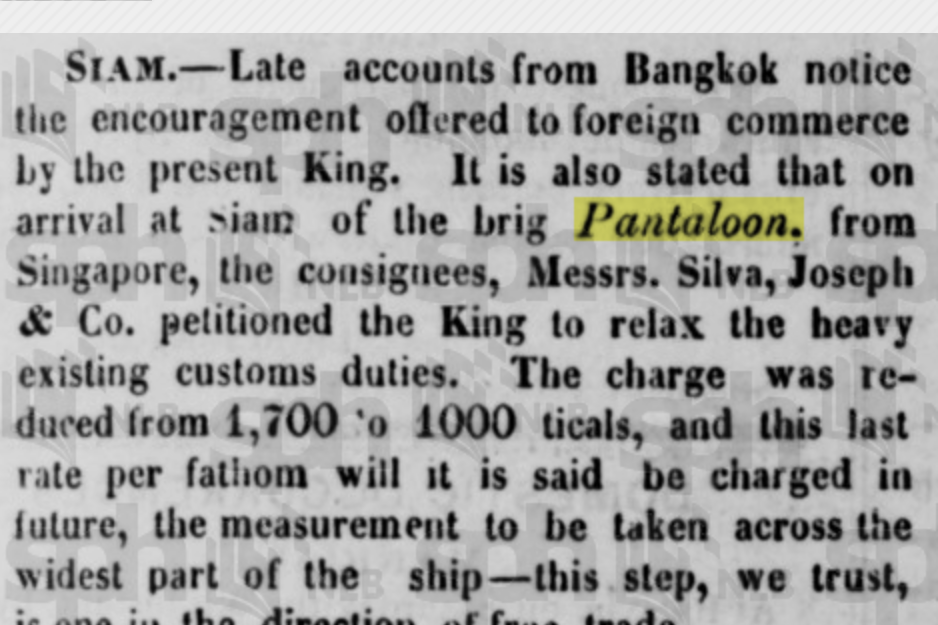

Always on the outlook for business opportunities, Helms had taken in 1851 the offer extended by the Singaporean firm Almeida & Sons to explore potential commercial relations with Cambodia. The expedition was facilitated by King Ang Duong’s representative in Singapore, Constantino de Monteiro, who had studied English in the Settlement. For this expedition, which was aimed at helping in suppressing piracy on the Cambodian coasts, Helms managed to enroll the captain of the famous British brig Pantaloon, Cpt. George D. Bonnyman, and he sailed as supercargo of the 323-ton warship loaded with merchandise to Kampot, and Bangkok. [see his account in ‘Cambodia in 1851’, JIAEA, vol 5, 1851.] He brougt back a large cargo of rice, pepper, raw silk, ivory, tortoiseshell, cardamom, gamboge, and stick-lak, along with a petition from the king for British protection. At that time, he already sensed that the French Empire was eying Cambodia and Cochinchina with increasing interest.

The Strait Times reported that Helms and the brig Pantaloon sailed back to “Kongpoot” (Kampot) and Siam in September-November 1851, persuading the King of Siam to “relax the heavy customs feees” on shipments from Singapore, from 1,700 to 1,000 ticals.

[1] Quoted by Estelle Gardner, Footnote to Sarawak [notes on the life of Ludvig Verner Helms], 1965, edited by

by Nancy P. Roe, Rebecca P. Roe, & Timothy W. Clapp, 2021, 363 p.. This is the most exhaustive study on Helms’ life and achievments to the day. [part of this study was published in Gardner, Estelle, “Footnote to Sarawak, 1859-”, Sarawak Museum Journal (SMJ) 11 no. 21/22 (July/Dec.1963), p 32 – 59.]