Pioneering in the Far East, And Journeys to California in 1849 and to the White Sea in 1878

by Ludvig Verner Helms

A valuable, firsthand account on Ang Duong's Cambodia in 1851.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- W.H. Allen & Co., London

- Edition

- ADB digital version via Internet Archive

- Published

- 1882

- Author

- Ludvig Verner Helms

- Pages

- 408

- Language

- English

pdf 24.3 MB

“In September 1846 I left my native land, Denmark, to seek my fortunes in the world. It seems strange, in these days of screw-steamers and swift travelling by land and sea, to recall the long and wearisome voyage on board the Johanna Caesar, as the little brig in which I had embarked was called.” The opening lines of L.V. Helms’ book — a blockbuster in the Anglo-Saxon world, yet too often ignored in French bibliographies related to Cambodia — show us this wide-eyed young man sailing to Bali and to legendary Danish merchant Mads Lange, at the start of a life of travels, successful and disastrous business deals, involvement in the Malay Peninsula colonization and, incidentally, firsthand experience of Ang Duong’s Cambodia.

Helm’s commercial and strategical expedition to Cambodia and Siam from February to June 1851, as the supercargo of British brig Pantaloon and with the company of Constantino (Constantine) de Monteiro, Ang Duong’s representative in Singapore who was then approaching both British and French officials in order to protect his country from his powerful neighbors Siam and Vietnam, occurred at a turning point in the history of Cambodia. It also came after a spectacularly unsuccessful business foray into California, when he had to leave San Francisco in a hurry:

About the 12th of September [1850, on the Indianeren], the vessel was at last ready to sail, and I went on board, but to find a difficulty-only nine of the crew of twenty-two had stuck to their duty; these did not suffice to raise the anchor, and we had to send on shore for men to do it. At last all was ready, and the tide soon took us out of the harbour. “I thank my stars that I am once more master of my own ship! You will never catch me in that accursed place again,” said the captain, as with a sigh of relief he looked towards the Golden Gate, now fast fading from our view. But though the captain had got his ship safely out to sea, his troubles were not over. Dangerously under-manned, we were yet to be still more crippled. Sickness broke out; the chief officer died within a few days, the captain at the same time being seriously ill, and some of those left were more or less ill. It began to look very serious, and had bad weather come on some disaster would have happened. Luckily, we had gentle, steady breezes, and a smooth sea. I had, however, to stand for days at the helm, but it is no hardship to guide a ship before favourable winds in fine weather.

Gradually our invalids recovered ; we crossed the Pacific in safety, and reached the coast of China without accident. We remained a few days in Hong Kong, and then continued our voyage to Singapore [arriving on 22 December]. The Californian speculation had been disastrous to my friends; there was no question of further enterprises in that direction. I therefore accepted an offer from my late employers to go as their agent to Borneo ; but as some months would yet pass before I could enter upon my duties there, I meanwhile undertook voyages to Cambodia and Siam. [pp 92 – 3]

Although this account was published much later, in 1882, we have found Helms’ relation to his trip to Cambodia published the same year he overtook it, in 1851.

CHAPTER III CAMBODIA AND SIAM

[out of 9 chapters in the book]

At this period, the attention of commercial men in Singapore had for some time past been directed to the kingdom of Siam and its dependencies. This country had formerly claimed suzerainty over the entire Malayan peninsula down to the very Straits of Singapore, and had carried on an important trade with Europe, in which many English ships were engaged, but during some years this trade had been gradually dwindling away. The cause of the decay had been the system of monopoly practised by the Siamese Government, and the hostile disposition latterly displayed by the old King Phra Nang Klau towards Europeans. To the merchants of the prosperous free port of Singapore this was an unsatisfactory state of things; they agitated at home, and at last induced the English Government to send Sir James Brooke on a mission to conclude treaties of commerce with Siam and Cochin China. This mission left Singapore in 1850, but failed, the Siamese Government having refused to enter into negotiations, and the relations with Siam became in consequence very strained. The trade with Singapore entirely ceased, and petitions were sent home by one party there, urging coercive measures against Siam. This state of things being perfectly well understood both in Siam and its tributary States, the latter saw in a rupture with England an opportunity for asserting their independence.

Amongst these States, Cambodia was the most important, as well as the one which had suffered most. Situated between Siam and Cochin China, it had been attacked and plundered by both in turn. When, therefore, the reports of the danger incurred by Siam reached Cambodia, the King sent an agent to Singapore to represent his situation, the capabilities of his country, and his desire to be friendly with the English, and to open commercial relations with them. An enterprising firm in Singapore [Almeida & Sons] resolved to put these assertions to a practical test, by sending a ship and merchandise, and the conduct of this mission was entrusted to me.

In former days Cambodia was approached from the China Sea, through the great Cambodian river the Mekong, and large ships used to ascend that stream upwards of a hundred miles, to a point where four arms unite into one great river, which falls into the China Sea at Saigon; but as the Cochin Chinese had long ago closed this waterway to Cambodia, the only means of approach now was from the Gulf of Siam, and the village of Komput (Kampot) remained the only port open to the Cambodians. For this place we accordingly laid our course when, in February 1851, we lifted our anchor in Singapore harbour, having on board the King of Cambodia’s Agent, Portuguese by descent [Constantino de Monteiro]. From the Gulf of Siam we made for Komput, which proved more difficult to find than we had expected, as the coast line was incorrectly laid down in the Admiralty charts; according to it, we must have sailed eighteen miles inland. At last, however, we found the place, and anchored in a picturesque gulf, bounded to the east by the islands and coast of Cochin China, and on the north and west by the mainland and islands of Cambodia. Of the village or town of Komput, nothing was, however, to be seen from the ship, which, owing to the shallow water, had to anchor ten miles from the shore. The Gulf of Siam was in those days greatly infested by pirates, and Komput, being then an unknown port, as yet unvisited by European vessels, was more than suspected of being one of their chief stations; in fact, many of the Rajahs and princes in the Eastern Archipelago were more or less directly engaged in piracy, and I was not by any means sure that the King of Cambodia, of whom nothing was known, would form an exception.

We, however, had come by his invitation, and he would expect this first visit in modern times of an English vessel to result in important benefits to his country and himself, by the opening up of commercial relations with a British settlement, and perhaps directing the attention and sympathy of Englishmen to his country. There was every reason, therefore, to expect that he would protect us as far as his authority went; but the question was, as to his power. However, we were merchant adventurers, and had to take men upon trust, and so, getting into the ship’s boat with my companions, we reached — after a couple of hours’ sail — the mouth of the river upon which the town is built. The stream is about three hundred yards wide, and the banks are well wooded with fine forest trees, among which is found in abundance a magnificent tree which is largely used by the Chinese as masts for their junks.

A couple of miles up the river the town came in sight — a miserable collection of thatched bamboo huts, surrounded by filth and mud, strongly reminding us of the Malay villages on the other side of the gulf; but the population seemed to consist mainly of Chinese, and apparently of a very depraved, emaciated, opium-smoking class. One of these huts, somewhat apart from the market-place, and untenanted, was placed at my disposal, and having obtained an interpreter, I sent him for some of the most respectable Chinese in the place, and gathered what information I could from them. I gave them particulars of the goods which composed our cargo, and eventually disposed of a considerable number of boxes and bales, the contents of which were to be taken in payment for the produce of the country, to be collected by them.

Meanwhile, we received a visit from the Governor, who combined a savage dislike to foreigners with an intense greed for bribes. Fortunately, Monteiro possessed experience and influence which served which served, to some extent, as a protection against the avarice of this greedy official, on whom we depended for means of proceeding inland to the royal capital. The cunning subterfuges and crafty dodges by which he endeavoured to protract these arrangements, with a view to black mail, were very creditable to his ingenuity; but as neither my temper nor resolution were affected by them, the means were at last forthcoming, in the shape of nine or ten carts drawn by oxen. On the 3rd of March, we started on our journey, making very slow progress. The oxen were poor; the carts worse. These latter consisted of a number of hoops covered with matting, and resting on two wheels, of course without the ghost of a spring. In this funnel-shaped conveyance I made my bed, and so travelled in a reclining position. The road, after traversing a marshy plain, led through magnificent forests, containing groves of bamboo, wild mango, and various species of palms.

They were full of wild animals of all kinds. Water was very scarce, as we never came across any streams, and the ponds — whence travellers were usually supplied — were dried up, and contained only a thick, green, slimy substance, quite undrinkable ; but in such places the margins were trampled by animals, as though a cattle-market had been recently held there. Here were the footprints of the elephant, rhinoceros, wild buffalo, tiger, leopard, boar, and deer. As a rule there was little underwood, and far away, under the leafy canopy, we could see the animals grazing, while overhead were the peacock, parquet, eagle, pigeon, &c.

We were, therefore, never without game for our meals when we encamped, but had rarely anything to drink. Occasionally we succeeded in quenching our thirst with the delicious toddy of the palm; but as our food supply consisted almost entirely of rice, and we could not eat it raw, we had — however repulsive it might be — to make use of the aforesaid unwholesome slimy water for cooking purposes. lies about 135 miles to the north-east of Komput; but the road to the capital is nearly 200 miles long. The dry sandy soil made travelling heavy and slow, and our progress did not exceed twenty miles a day. The carts constantly broke down, and had to be repaired with such means as could be found in the forest, in the shape of rattans, &c. Human habitations were rare. Now and then we came to a Buddhist monastery, but the monks, though they looked picturesque in their long yellow robes, were of little use, having nothing to offer us.

At night we formed the carts into a camp, having the cattle in the centre, and kindled fires all round to keep out wild beasts. On the fifth day we reached a village where we were to change our draught animals, but the people assured us that they had none. Monteiro, however, knew better. He had the headman put into the stocks, and the animals were at once forthcoming. We learned here, that a number of elephants had passed on the previous day, having been sent by the King to meet us, to expedite our journey; but they had missed us. At the few villages which we passed, the people crowded round to see us; they appeared a wretchedly poor lot. Though I had brought with me all sorts of tempting trifles, with a view to barter for food or curiosities, they could offer us nothing. On one occasion — when halting at such a village — I was wandering about in the wood with my rifle, and seeing a wood-pigeon in a very high tree, I by good chance brought it down with a bullet; the people regarded the performance with surprise. Presently they brought out an elephant’s tooth, which they told me was of priceless value, as no one wearing it could be hit by arrow or bullet. The tooth was a good size, and would, at thirty or forty yards, offer a fair mark. I, therefore, suggested that they should let us have a trial at it, to which they willingly consented. We accordingly all had a shot by turns. I was not at all surprised at missing it myself, though, after my late performance, it seemed to impress the people, but I was vexed to see one of my companions, who was really a good shot, miss it also. The charmed tooth was carried away in triumph; nor could our arguments convince them that our bad shooting, and not the virtue of the tooth, was the cause. I believe that no money could then have bought it. Some of the aborigines in Cambodia, known as Stiens, use the cross-bow when hunting, and they bring down even the elephant with their poisonous arrows, which, I was told, take effect very quickly.

On the evening of the tenth day we at last reached Oudong after a very fatiguing journey. We were all worn out, and I was bruised and stiff all over. We found to be a very poor-looking place like Komput, composed of thatched bamboo huts, but containing, according to native statements, about 10,000 inhabitants.

The fact is, that the town had been so often burned down by the Annamites or Siamese enemies, and was so likely to suffer this experience again, that it was hardly worth while to build substantial houses. A bamboo house was assigned to us; but our first night was not destined to be a comfortable one. We were disturbed by hideous noises, which we soon recognised as the howl of jackals — a peculiarly horrible sound. Ere [sic, Before?] long, numbers of them surrounded our house.

As there was room between the bamboos of the walls to push a gun-barrel through, we kept up a steady fire at them, but without any great effect, as the night was dark. Though the present condition of the country is one of poverty and decay — the capital itself steeped in filth, which invites the jackal by night, and the vulture by day; for these loathsome birds are seen everywhere, even round the King’s palace — yet there are still signs of the departed greatness of the country in the astonishing remains of the ruined palaces and temples of Angkor [1], the ancient capital of Cambodia, which was situated towards the northeast, on the banks of the Mekong, and was the residence of monarchs who ruled the mightiest empire in the far East, embracing part of the present China in the north, and of Burmah in the east. The traditions still preserved, tell of twenty kings who were tributaries to the ancient sovereigns now represented by the King of Cambodia, himself now protected by the French Government at Saigon. In the centre of was a large square surrounded by walls with fortified gates on each of the four sides. Within the square was the King’s palace, protected by a second wall. It was not a very pretentious building, being of wood, and of the same temporary character as the rest of the town. The King had sent a message to invite our attendance, giving us at the same time a hint not to talk politics, as emissaries from Siam and Cochin China had, he said, arrived to inquire as to the meaning of so unusual an occurrence, as the presence of an English ship at Komput.

At this time the King of Cambodia was Prah Harirak, or Ongduong. He was about fifty years of age, and had ruled Cambodia seven years. Fifteen years before, the Cochin Chinese of Annam had protected the Cambodians from the attacks of the Siamese, and had placed on the throne a princess named Neac Ong Ban. The unfortunate Queen being detected in a correspondence with her relations, was condemned and decapitated by the Anna mite General, who placed her sister on the throne; but after a series of revolts and massacres the oppression of the Cochin Chinese compelled the Cambodians to appeal to the King of Siam, who, after defeating the Annamite troops, restored order in the country, and placed Ongduong on the throne. He was, however, constrained by the Siamese to promise tribute to the King of Cochin China, and the latter agreed to join Siam in recognising him as King of Cambodia, and leaving the country in peace, undisturbed by the invasions which had been an annual infliction.

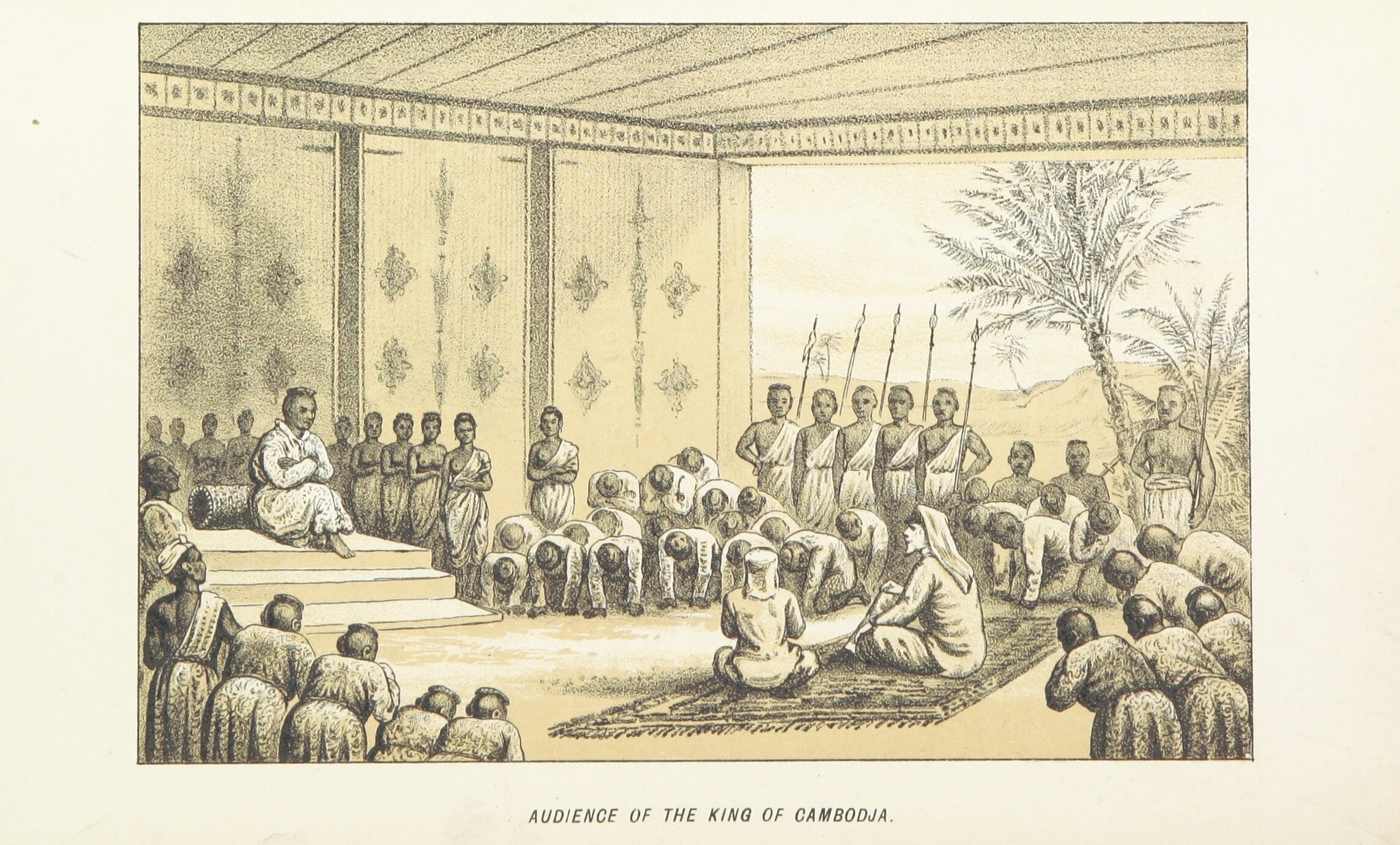

The King, whose full style and titles were Phra Maka Harirak Issara Tibodi [2] was not only a tributary of Cochin China, but also a vassal of Siam, and might not leave the country without the permission of the King of Siam, while his eldest son, Rachabodi, had been sent to Bangkok as guarantee of his loyalty to Siam. Subsequently to my visit at I made this young man’s acquaintance in Siam, and then thought that doubtless he and the country which he might be called upon to rule, would benefit by the teachings which the somewhat more advanced and settled condition of Siam could afford him. At the appointed time, the King received us in audience with rather a poor attempt at regal state. There was a sort of throne, and the assembled pages and nobles who were all dressed in red gold laced coats, were lying on the floor, awaiting the monarch’s arrival. I found that the proper head covering for full dress was a hat resembling that worn by stage banditti, with a high-pointed peak and a very broad brim, the hat-band being replaced by a species of coronet. The early Portuguese navigators must, I think, have introduced these, to which they appeared to attach much importance, and as those now in use were in a very dilapidated condition anxious inquiries were made as to my ability to supply new ones. Head-coverings seemed, in fact, to be a weakness in courtly circles at Oudong ; for when invited to the audience, I was asked whether it was true that Europeans usually wore a black hat of a very peculiar construction. When I had admitted this, and given a description of it, much disappointment was evinced on learning that I could not gratify His Majesty by appearing in the European hat.

The King, a middle-aged, comfortable, somewhat heavy, but benevolent-looking man, with features deeply marked by small-pox, now made his appearance. He was surrounded by a crowd of women — mostly young girls — who did not in any essential way differ in appearance or dress from Malay women; except that their heads were shaved, leaving only the Siamese tuft of short, bristly hair; the teeth were filed and blackened after the disgusting Malay fashion; the sarong also was gathered up, and fastened with a girdle, the bosom being covered only with a salendong. They were, doubtless, fair representatives of the two or three hundred said to inhabit the royal Zenana.

The King expressed himself as being very pleased with our visit, inquired as to our journey, regretting that he had been unable to do more for our comfort, and then, entering upon matters touching trade, told us of the former prosperity of the country, when large ships came up the Cambodian River; but he added that there was still a large trade to be done, and as a practical proof of this, on my return I brought back a valuable cargo of rice, pepper, raw silk, ivory, tortoise-shell, cardamoms, gambol, stick-lac, &c. A large quantity of buffalo hides and horns, having to be brought down a canal, were intercepted by the Cochin-Chinese. Having conversed with us for some time — amongst other things upon the subject of the currency of the country, and intimating that he wished me to procure him a coining machine (which was subsequently sent to him) — the King entered upon business with his officials, most of whom had some report to give, which appeared occasionally to cause great amusement. We took our leave, after having offered to the King some handsome presents, which were graciously accepted.

We were twice invited to the King’s private apartments, which, as far as appearances went, might have been a pawnbroker’s shop in a poor locality. There were, of course, some valuable articles there, but it was a singular medley of things — Japanese, Chinese, Malay, and European manufactures, arranged in a manner which showed that neither their value nor their intended purposes were understood. We were entertained very hospitably, most of the dishes being of the nature of stews, prepared in Chinese fashion; as to the composition of which, it were better not to inquire too curiously. The King honoured us by his presence, though he did not join in the feast, but went round, pointing out the delicacies, carrying all the while his youngest son, of whom he seemed very proud. He subsequently conducted us through a very neat garden, and on leaving, presented us with silk stuffs which had been woven in the palace. An elephant of huge size was subsequently offered, but this I gratefully declined to accept. During this visit, the King had been more communicative as to the state of the country. He said that he was very anxious that English ships should again come up the river; but when I asked him as to protection through Cochin China, he said, ” Good heavy guns will be your best passport.”

Two French missionaries arrived from the interior to see me. They had heard of the arrival of an English ship, and having had no news for years from the Western World, had bought an elephant, and made a fatiguing journey. They told of dreadful persecutions which the missionaries endured in Cochin China; they themselves had been imprisoned in underground dungeons and tortured, and had narrowly escaped the death which had been the portion of many of the converts and some of their brethren. They were eager for news, and astonished to hear of the Revolutions in Europe and the dethronement of Louis Philippe.

I made several excursions on ponies covered with bells and gaudy trappings, and visited several settlements on the Cambodian River, which here is a magnificent broad stream. On the banks were thousands of storks, herons, and other aquatic birds, but the bustle of the commerce once carried upon it was no longer there. There were few boats on the river, and the settlements upon the banks were few and scattered. We spent about a week at and then returned on elephants, which was a quicker mode of locomotion than carts, and not nearly so fatiguing. So long a journey on elephants, was, however, a new experience, and on one occasion it became an exciting one. We found the forest on fire, the animal took fright, set up a startling roar, and bolted at a pace something between a trot and a gallop, but at a prodigious rate, which made the howdah sway like a boat in the sea-way. I was a little alarmed as to the consequences, but he was finally brought under command again; otherwise, we used to be on excellent terms. A large quantity of Chinese sweetmeats had been given me at and as I did not relish them, I used, at halting-places, to regale my elephant, who was delighted with them. Having completed the loading of the ship at Komput (Kampot), we set sail for Singapore, which we reached in the middle of June. Thus ended ray journey to Cambodia, of which the result, from a commercial point of view, was very satisfactory, and inaugurated a trade which has since been increasing; but Cambodia will never recover even the shadow of its former prosperity, till the Mekong, the magnificent highway which nature gave it, shall again be available from its upper waters to the sea. When returning from Cambodia, I fulfilled my promise to the King to plead the interests of his country, and I had hoped that English enterprise would set in in that direction; but subsequent events threw these regions into the hands of the French. It suited the policy of Napoleon III to renew French prestige in this part of the world.

The cause of religion, and the cruel treatment of French missionaries, was the pretext for interference, and it can scarcely be a cause for regret that this should be so; but when I visited Saigon twenty years later I could not help seeing that the French — though a people with noble instincts, a highly gifted and great nation — yet have not the art of colonising. In the evolution of time there will probably again be a great future for the beautiful countries of Indo-China and the Eastern Archipelago generally; but though Western civilisation will doubtless supply the motive power, the real work of rehabilitating them must be supplied by other races. It has already been mentioned how a recent mission to negotiate a Treaty of Commerce with Siam had failed. The King would not receive the British plenipotentiary, and it was thought that the British Government would take offence, and force Siam into a more friendly course. Petitions, both for and against coercion, were sent home from Singapore, and Siam was preparing for defence. On the eve of leaving Cambodia, a rumour had reached me that the old King of Siam was dead, and this had caused some interest among the commercial community at Singapore, for it was known that the heir to the throne was an enlightened man, and well-inclined towards Europeans. Under these circumstances it was thought possible to renew commercial intercourse with Siam. [3]

I was asked, and gladly consented, to make the attempt; I was to call at the ports on the Malayan coast going up, in order to ascertain the truth of the rumour, as to the King’s death, and only if it was confirmed, to shape my course for the river Menam. Our vessel bore quite a warlike aspect; she carried no less than ten guns [4], which, however, as there were frequent acts of piracy in the Gulf, were not unnecessary. Having left Singapore on the 23rd of June, we passed Cape Roumania, the southernmost point of Asia, and had before night left the well-known rock Pedro Branco out of sight. Sailing pleasantly along the low forest-clad coast of the Malay Peninsula, we found ourselves on the fifth day off and anchored within two miles of the river. I landed, and went to the house of the Chinese Bandar, with whom I was well acquainted, but found him absent.

Meanwhile messengers came to invite me to the Rajah’s presence. His Highness, who was sitting in an open shed, was very friendly and full of questions as to the object of my trip, but as I came to seek information, not to give any, and he either could not or would not impart any respecting affairs in Siam, I soon took my leave. He told me, however, that he had lately taken three piratical boats, and pointed towards three large junks, partly burnt, in one of which twenty-three men had been killed. A few years before this same Rajah was one of the worst pirates on the coast, having a number of piratical crafts cruising about on his own account; Singapore being so near, he now found it more convenient to pose as the suppressor of piracy, but whether these boats really were pirates, who could say? I was assured by Chinese that one of them at least was not.

We continued our course north, with light sea breezes by day, and the land wind at night, and the unbroken forests of Malacca always in view. We were next to call at and on the 30th, towards evening, we came in sight of five large Chinese junks at anchor, and as we doubted not this was the place we were seeking, we bore down for it, but the junks looked very suspicious; and as trading junks ought long before to have left for China, we began to suspect that we now saw before us the piratical fleet of which we had heard at Cambodia; we, therefore anchored at some distance, opened our gun-ports, and gave ourselves, as much as possible, the appearance of a man-of-war, which apparently had the desired effect, for the next morning the suspected crafts had disappeared. It took three hours’ pull to reach the town, which is ten miles up the river. I made for the Rajah’s house, followed by a crowd of people. Just as I reached the place, two newly-caught elephants were brought in, followed by a number of tame ones, which apparently had been employed in the hunt. These Rajahs all being tributary to Siam, were greatly interested in the precarious relationship in which that country was now understood to stand to the British Government. They were well acquainted with the failure of Sir James Brooke’s mission, and would apparently have liked a war. As regarded the death of the King, they professed ignorance, though admitting that rumours to that effect were about. The next state on the coast, Sankara, was reached on the 4th July.

The Rajah of this country is a vassal of Siam, and the people looked more like Siamese than Malays. I expected to obtain reliable news here, and, partly to avoid losing time, partly that our vessel might run no risk from pirates, which we learned had, a short while ago, actually carried off the Rajah, holding him at a ransom of 10,000 dollars, we anchored eight miles from the coast, and I went ashore. The residence of the Rajah was surrounded with walls; he was a pure Siamese, and I had to converse with him through an interpreter. He was extremely civil, though shy in imparting information about Siam, but told me that the old King was really dead, and so, at last, I had obtained the news which would justify me in shaping my course for Siam, and two days later we anchored at the mouth of the Men am. Three Siamese vessels were lying at anchor outside, ready to sail for China, with tribute from the new King to the Emperor of China. I was told that I would probably meet with a friendly reception.

This was cheering, and I at once prepared to proceed to Bangkok, still some forty miles distant. Leaving the vessel at noon, I arrived at Paknam at three in the afternoon; this was a rather dirty town, with a fortress, protecting the entrance to the river; and here vessels bound for Bangkok, had to undergo inspection, and to leave all arms, ammunition, and stores of a war-like character. The forts were not of a very formidable nature, as against a European foe, though, doubtless, capable of defending the river against any native attack. The commandant in charge was greatly surprised at seeing the British flag, and could not understand how news of the King’s death could have reached Singapore. He evidently thought my coming there a somewhat audacious act. I explained that I had, during a late stay in Cambodia, heard the news of the King’s death. “Ah I” he said, “are you the one who has been visiting the King of Cambodia at Oudong? Then we know all about you; but you must return on board, and in a couple of days I will send you word as to the King’s pleasure regarding your taking the vessel up to Bangkok.”

But delay did not suit me; I was well acquainted with native tactics, and knew that this might mean indefinite procrastination, and I thought that the Siamese Government, being now desirous to conciliate English interests, were unlikely to send the first ship under English flag, inhospitably away. I therefore intimated that if they sent me on board again I should not return. This had the desired effect, and, after a couple of hours’ delay, I was permitted to proceed up the river, a messenger having meanwhile been despatched with the news. I left the fort at 8 p.m., and did not reach Bangkok till 11 next day, having sailed and pulled by turn all night; when, some days later, I again leisurely ascended the river in the ship, often having to anchor when the tide was against us. I used frequently to land, and, seeing large numbers of pigeons on the roofs of the pagodas and temples, I thought it a good opportunity to bag some. I was thus busily occupied, dividing my attention between two of these sacred buildings, firing away right and left, and had already secured several birds, when loud shouting made me look round, and I saw a crowd of yellow-robed Buddhist priests, armed with sticks, rushing towards me, evidently much excited. It had not occurred to me that I was on forbidden ground, but as there was no mistake that hostility was intended, I beat a hasty retreat to my boat, and made a note about pigeon-shooting in Siam.

The approach to Bangkok is picturesque, the river is skirted by gardens and plantations; the trees and vegetation generally being very fine; and as the town is approached, richly decorated temples become more and more frequent. By and by rows of floating houses come in view, which show that Bangkok is reached. The plateau on which the city is built being low, and subject at certain times of the year to the inundation of the river, these floating shops, which can be moved from place to place, are very convenient.

The houses on terra firma are, as a rule, built upon posts, like Malay houses. Siam, like Cambodia, and the Eastern Archipelago generally, is a country with great natural resources, but very partially developed for want of population, which is estimated at 6,000,000, but probably without reliable data. Siam is mainly a level plain, formed by two spurs of mountains, which are offshoots of a great mountain chain which runs through the southern provinces of China. This valley, watered in its whole length by the river Men am, which, like the Nile, yearly overflows its banks, leaving an alluvial deposit, is very rich for agricultural purposes. Rice, sugar, coffee, and other produce is largely grown, and the fruit of Siam is, in quality, amongst the finest in the East. In minerals also the upper part of the country is probably rich, but they are but little worked. The people are inclined to be indolent, and here, as elsewhere in these parts, it is the Chinese who are the leaven, and who, though as yet forming but a small fraction of the population, are foremost in agricultural pursuits.

As traders, however, they have not got it quite their own way, for the Siamese nobles, and even the princes, engage largely in trade, and at the time I was there, monopoly was the order of the day. The system is doubtless disappearing as time goes on and treaties with European States come into force; but the demands for Western manufactures by a nation, the bulk of which is still living in a primitive manner, must continue limited. European merchants will, also, experience keen competition from the natives and Chinese. At the time of my arrival European trade with Siam had for years languished; the Portuguese, and after them the Dutch, had been the first in the field; but their factories and influence no longer existed. French enterprise had mainly been directed towards the extension of the Church, and England had not been very successful in her negotiations for treaties. Crawford failed in 1822. The treaty concluded by Burner in 1826 still made British subjects amenable to Siamese laws, and, finally, Sir James Brooke’s mission in 1850 had, as we have seen, proved a failure, as had also that of Mr. Ballsier on the part of the United States.

One Portuguese gentleman was the only representative left of European merchants. To him I had letters of introduction, and was received with the greatest kindness and hospitality. One of the obstacles to foreign trade in Siam, was the oppressive mode of levying duty on ships. The usage was, to take the measure across the deck, and to pay accordingly. Besides the amount thus charged being excessive, this acted unfairly for vessels of small burden.

I therefore determined that if they wanted my ship to come up the river, they should grant me this concession; and when the following day, I was admitted to an interview with the or Foreign Minister, I told him of my intention. He promised to do his best, which promise I fortified, according to the custom of the country, by liberal presents; nor was I deceived, in due course I was informed that not only was my request granted, but that the King intended to give me an audience, and what was more, it was to be an audience of a public and imposing character — in order, as I was informed, that this change of an old custom of the country might be made in the presence of the notabilities of the state.

I should here mention, that the King just deceased, being an illegitimate son, had no right to the throne; his half-brother, the present King’s father, had been the real heir, and this man’s son, fearing that his uncle might think it necessary to firmly establish his throne by removing him, sought safety within the monastic walls, and became a Buddhist monk. To this he probably owed his erudition, which in some branches of knowledge ‑for instance, astronomy — is said to be considerable. He also had a knowledge of many Eastern languages, including Sanskrit, as well as of Latin and English, all of which was partly due to missionary instruction, but mainly to self-teaching. His greater knowledge had doubtless helped him to a better appreciation of the outer world, and his country’s relations to it, than his predecessor had possessed. That very curious office in Siam, of Second King, was occupied by the King’s brother; though not really invested with kingly powers, he, nevertheless, enjoyed many privileges not allowed to the lieges. He also had enlightened ideas, and a desire to adopt European civilization ; he had a guard in European uniform, and owned a small steamer, said to have been constructed under his own supervision, was in fact, a well-informed man, desirous to promote the well-being of the country. On the day appointed for the audience, I went with my Portuguese host, in a handsome barge, to the palace, or rather that quarter of the town occupied by His Majesty — a large space, surrounded by high walls, and containing temples, barracks, and dwelling-houses, for the royal retinue, which probably number several thousands; the royal wives alone amounting to over 500. Having arrived at the palace, we were shown into a room where we had to wait some considerable time. Here there was a large gathering of officials in their gayest attire. The princes and great officers of state were, however, still to come, and one by one they arrived, carried in magnificent sedan chairs, each with a following of from ten to thirty men; the emblems of their dignity — golden swords, teapots, and sir i‑boxes — being carried before them upon silken cushions.

We had been kept waiting outside the inner walls of the palace, but they were now all called away, except my companion and myself. After a while we also were invited into an open space in the centre of which was the audience hall. A guard of about 200, in European uniform, white trousers and red coats, was drawn up at the entrance to the outer hall. We were received by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, with whom was an interpreter, and the Master of the Ceremonies, in a court dress, given him, as he informed me by Sir James Brooke. The ticklish question of ” kowtow,” or kneeling in the King’s presence, was got over by allowing us a low seat. A magnificent golden screen stood in front of the porch leading to the inner hall. After stepping past it, I saw the Siamese monarch sitting, or rather reclining upon his throne; the Prime Minister lying on the steps, the Princes on either side, right and left, while the councillors and courtiers, a couple of hundred of them, lay in two long rows on their faces on either side of the hall. The sight was a novel and rather gorgeous one. The throne, which was raised several feet from the floor, was richly gilded; on either side was a golden and silver tree.

The King, whose lower garments and girdle were glittering with gold and precious stones, was naked to the waist, unlike his courtiers, who all were dressed in rich robes or jackets. He seemed past middle age, was thin, fair complexioned, and had an air of good nature; being in mourning for the late King, his head was shaved, the usual custom being to leave a tuft of hair over the forehead. Before him lay a golden sword, with which

be was now and then playing during the audience. But all this state left nevertheless an unpleasant impression of the abject servility of the scene. It was distressing to see this crowd, many of them fat old men, in this uncomfortable crouching position, resting on knees and elbows, and not daring to lift their faces during the whole of the audience. It represented but too faithfully the condition of the people; for as the nobles here prostrate themselves before the King, so do they, in their turn exact homage and slavish obedience ; and so on, through every class of the people, one class only excepted, viz. the “talapoins,” or priesthood; they alone stoop to none. but on the contrary, though living upon alms, they receive these with unconscious indifference, the giver offering his alms with due humility; absorbed in self-contemplation, the Buddhist priest is dead to the outer world, and disregards all that goes on around him.

The audience did not last long. I was asked to state my business, which was done, and repeated by the interpreter. The King then asked a number of questions, showing that he knew all about my visit to Cambodia, and on the Malayan coast; inquired also as to the feeling in Singapore towards Siam, and wound up by granting my request, stating at the same time that he expected the British Government would again send an Ambassador to Siam,

when a treaty would be formally concluded. It was his wish, he said, to do all in his power to encourage European commerce, and he felt sure that the introduction of European capital into the country would have the effect of greatly increasing the production of the staples of the country, and especially of sugar.

I had written a letter congratulating the King upon his accession, which was handed to him, and to which he, sitting upon the throne, wrote the following answer: “Compliments and thanks from Somdet Phra Parra-Manda, newly-exalted King of Siam, to Mr. Helms, 26th July, 1851”; and he ordered the great seal to be attached to it. Two days later, I had a similar interview with the second King, who had his troops reviewed in my presence, and on my departure presented me with a gold and silver flower, a sign of grace and good-will.

The Siamese being Buddhists burn their dead, and such a burning of the remains of two persons related to the royal family was shortly to take place, and to be the occasion of great festivities. It was the day before my departure, and the Foreign Minister received the King’s special request to invite me. There were, I was told, about 15,000

people present. The Kings arrived in great state, and, the burning over, there were all sorts of festivities, during which the King, who with his family and suite occupied the royal box, threw new golden and silver coins, concealed in lemons, amongst the people. I had my place near him, between the Foreign Minister and the son of the King of Cambodia, who listened with great interest to the account I gave him of my visit to his father’s residence at Oudong.

The King, on his departure, addressed a few kindly words to me, and invited me to settle in Siam. I likewise received much courtesy from the ministers; the Phra Kalahom (Prime Minister) entertained me at his palace, when, after refreshment, a theatrical performance was given by the inmates of his zenana. Presents in produce were returned, exceeding in value those I had offered ; they consisted of 200 piculs [5] of sugar, several piculs of gamboge, stick-lac, &c. Finally the Government entrusted me with a large order for all kinds of armaments, war-like stores, machinery, &c., to the value of over £20,000; in fact, I had every reason to be pleased with my trip.

[1] If this mention of Angkor has been overlooked by historians of Cambodia, we find quite telling that the author, without visiting the ruins himself, was struck by the Angkorean heritage inspiration at the Court of Ang Duong. This mention of Angkor, however, was not present in the first account of his visit, published in 1851.

[2] Here, as in the Cambodian royal succession breakdown, Helms was particularly accurate, probably thanks to de Monteiro. According to Mak Phoeun, the honorific name of Ang Duong (French transcription) Hariraks Rāmā (Aṅg Ṭuoṅ). His mother, Princess Samtec Braḥ Mahayyikā Khattiyāvans Ras’ [or Ros], King Narottam [Norodom]‘s grand mother, passed away in 1866. Mak Phoeun didn’t include Helms’ book in his bibliography for Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIeme…

[3] Phra Bat Somdet Phra Nangklao Chaoyuhua พระบาทสมเด็จพระนั่งเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หั (31 March 1788 — 2 April 1851), Rama III, eldest surving son of King Rama II, was succeded by his half-brother (son of Queen Sri Suriyendra) Mongkut มงกุฏ (18 Oct. 1804 ‑1 Oct. 1868), the fourth king of Siam from the Chakri dynasty. As Rama IV, he ruled from 1851 to 1868 and held progressive views that led Siamese elites to call him “The Father of Science and Technology”.

[4] About Pantaloon brig, see Helms’ 1851 account.

[5] A picul (Malay and Indonesian pikul, ch 擔 or 担, kr 담 jp 担 ), or tam,was a traditional Chinese unit of weight mostly used in southern China and coastal Southeast Asia, literally “as much as a man can carry on a shoulder-pole”, approx. 60 to 75 kg.

See a map of Cambodia drawn on the occasion of L.V. Helms’ visit

Read a detailed account of L.V. Helms’ visit to Cambodia published in Singapore, 1851

ADB note 1: there have been numerous reprints of the 1882 edition. The Kindle version (by HardPress, Miami, 2017) carries many unfortunate typos, such as “Miami” for “Siam”, “Panama” for “Paknam”, “Phrase” for “Prah” (Preah), “Compute” for “Komput” (Kampot), etc…

ADB note 2: thanks to Philip Coggan for pointing this important document to us.

Tags: Siam, Modern Cambodia, King Ang Duong, British travelers, commerce, 1850s, 1860s, Borneo, maritime trade, Malay people in Cambodia, Chinese people in Cambodia, British-French rivalry

About the Author

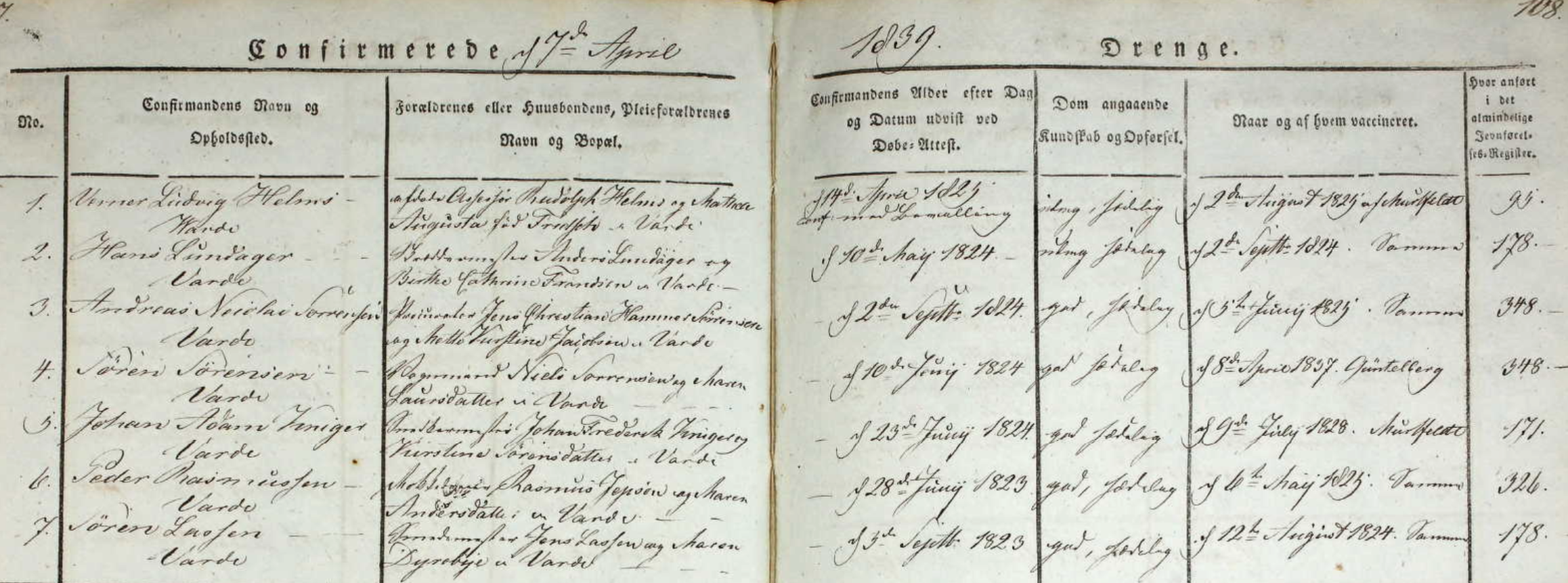

Ludvig Verner Helms

Ludvig Verner Helms [Verner Ludvig on his birth certificate] (14 April 1825, Varde, Denmark – 26 July 1918, Hampstead, England) was a merchant, explorer and author of Danish ascent who was active in trade across Southeast Asia during for twenty-eight years as a trader associated with British interests — MacEwen & Co, R.& J. Henderson- in Singapor, and the first manager of the Borneo Company Limited (BCL) — registered in London by the first Rajah of Sarawak James Brooke as a mining company in London in 1856, then adding banking activities — in Sarawak from 1852. He visited the court of King Ang Duong and Cambodia, as well as the one of King Rama IV (Mongkut) in Bangkok, between February and June 1851.

“In September 1846 I left my native land, Denmark, to seek my fortunes in the world,” Helms’ opening sentence of his sole published book, Pioneering in the Far East, aptly describes the life of an indefatigable traveler who thrice crossed the Pacific Ocean, sometimes at the helm of the ship carrying him — like in 1849, when the crew refused to come back onboard in San Francisco port during his first visit to California -, and went as far as the White Sea [Белое море, Arkhangelsk, Russia] and Lapland [Finland].

His ancestor, Adam Helms, was the son of a merchant from Lübeck, the Hanseatic League city where Martin Luther launched his Reformation movement. His father Rudolph, the first apotheker (pharmacist) in the small town of Varde on the North Sea died when Ludvig was eigth years of age, and through his elder siblings he heard of the adventures of Danish merchant Mads Lange, whose daughter Cecilie was to become Sultana of Johore. In a souvenir book he later wrote for his grandchildren, he wrote:

Young, full of health and spirits, and with all the world before me, I built a hundred castles in the air… There was indeed a great fascination about Bali, no one that I had ever come across had been to it, even in books there was little to be learnt concerning it, but that little was of a nature to excite one’s curiosity. It was described as a small paradise… inhabited by an interesting, handsome race of natives who were independent, proud, and unwilling to admit Europeans among them. One stranger only, this countryman of my own, had managed to establish himself there… Romantic stories of his doings, his influence and his wealth, were afloat. These had captivated my imagination, and… I had determined to visit him and offer him my services. [1]

Starting with Bali, where he was active in 1847 – 1849, Helms traveled around the world, visiting California, Cambodia, Siam (Thailand), Sarawak (nowadays a State of Malaysia) — where he built his house, called Anaberg, while also residing in Kuching during the local insurrection -, Brunei, Japan, Australia, the White Sea. At ease with grandees, he knew to stay self-possessed and critical. While visiting the powerful head of the Mormon Church in Salt Lake City, Utah, Brigham Young, the polygamist spiritual leader attempted to flatter him by praising Scandinavian women, but he wrote in his notes: “I must say that the appearance of those seen [there] did not seem to indicate that the peculiar institution had brought them much happiness.”

In 1858, during one of his trips back to England, he married Ann Amelia Bruce, then 20, one of the six children of Thomas Bruce, a Scottish businessman, and Louisa, a couple of Nonconformists who lived in Suffolk, whose eldest sister was in living in China with her missionary husband. They had six children.

Always on the outlook for business opportunities, Helms had taken in 1851 the offer extended by the Singaporean firm Almeida & Sons to explore potential commercial relations with Cambodia. The expedition was facilitated by King Ang Duong’s representative in Singapore, Constantino de Monteiro, who had studied English in the Settlement. For this expedition, which was aimed at helping in suppressing piracy on the Cambodian coasts, Helms managed to enroll the captain of the famous British brig Pantaloon, Cpt. George D. Bonnyman, and he sailed as supercargo of the 323-ton warship loaded with merchandise to Kampot, and Bangkok. [see his account in ‘Cambodia in 1851’, JIAEA, vol 5, 1851.] He brougt back a large cargo of rice, pepper, raw silk, ivory, tortoiseshell, cardamom, gamboge, and stick-lak, along with a petition from the king for British protection. At that time, he already sensed that the French Empire was eying Cambodia and Cochinchina with increasing interest.

The Strait Times reported that Helms and the brig Pantaloon sailed back to “Kongpoot” (Kampot) and Siam in September-November 1851, persuading the King of Siam to “relax the heavy customs feees” on shipments from Singapore, from 1,700 to 1,000 ticals.

[1] Quoted by Estelle Gardner, Footnote to Sarawak [notes on the life of Ludvig Verner Helms], 1965, edited by

by Nancy P. Roe, Rebecca P. Roe, & Timothy W. Clapp, 2021, 363 p.. This is the most exhaustive study on Helms’ life and achievments to the day. [part of this study was published in Gardner, Estelle, “Footnote to Sarawak, 1859-”, Sarawak Museum Journal (SMJ) 11 no. 21⁄22 (July/Dec.1963), p 32 – 59.]