Notes to Accompany a Map of Cambodia, 1851

by Angkor Database

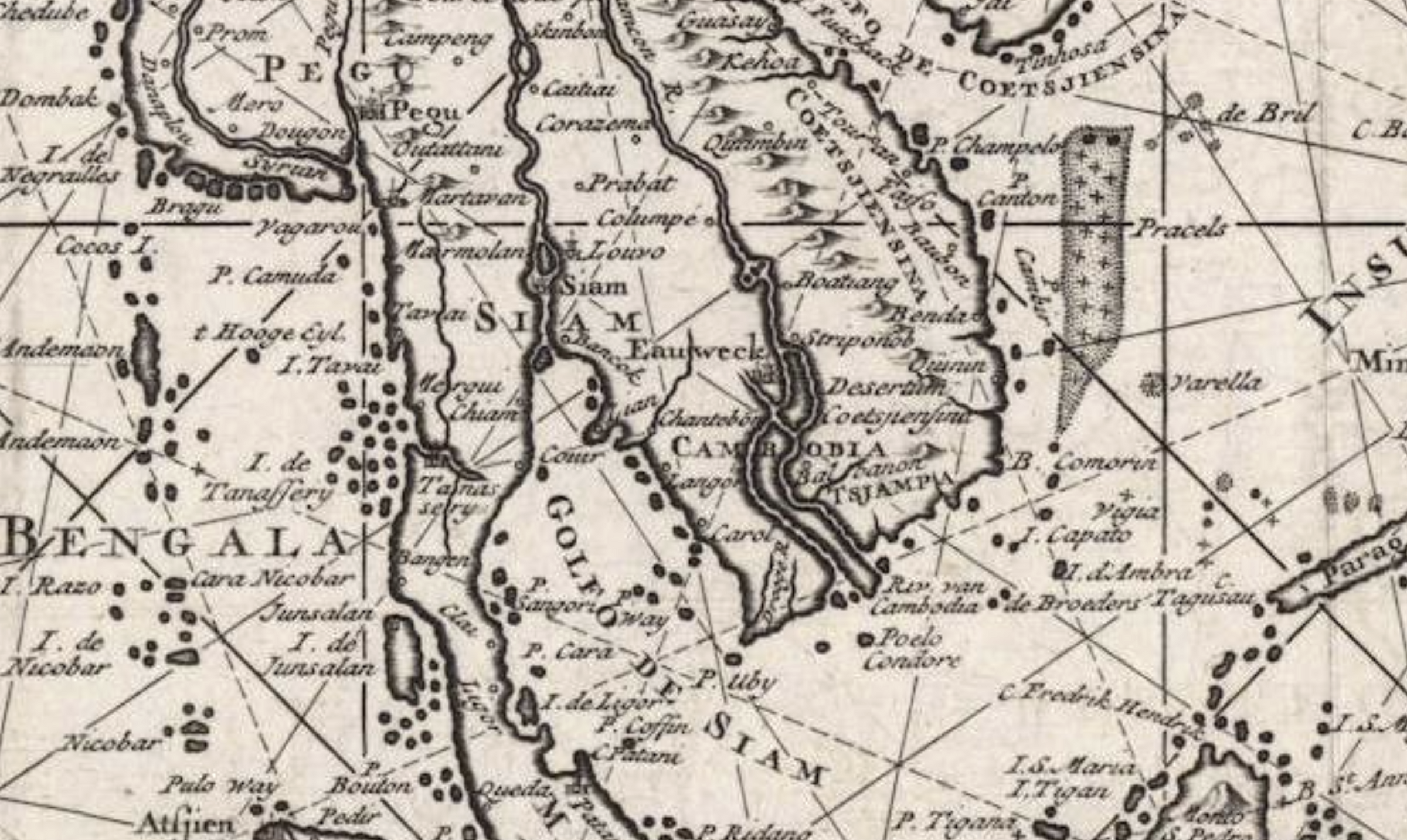

An early map of Cambodia drawn in Singapore with information from Constantine de Monteiro, King Ang Duong's representative.

- Publication

- Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA), ed. J. R. Logan, vol.5, Singapore, 1851, pp 306-11 [Kraus Reprint, Nelden, 1970]

- Published

- 1851

- Author

- Angkor Database

- Pages

- 7

- Language

- English

pdf 290.5 KB

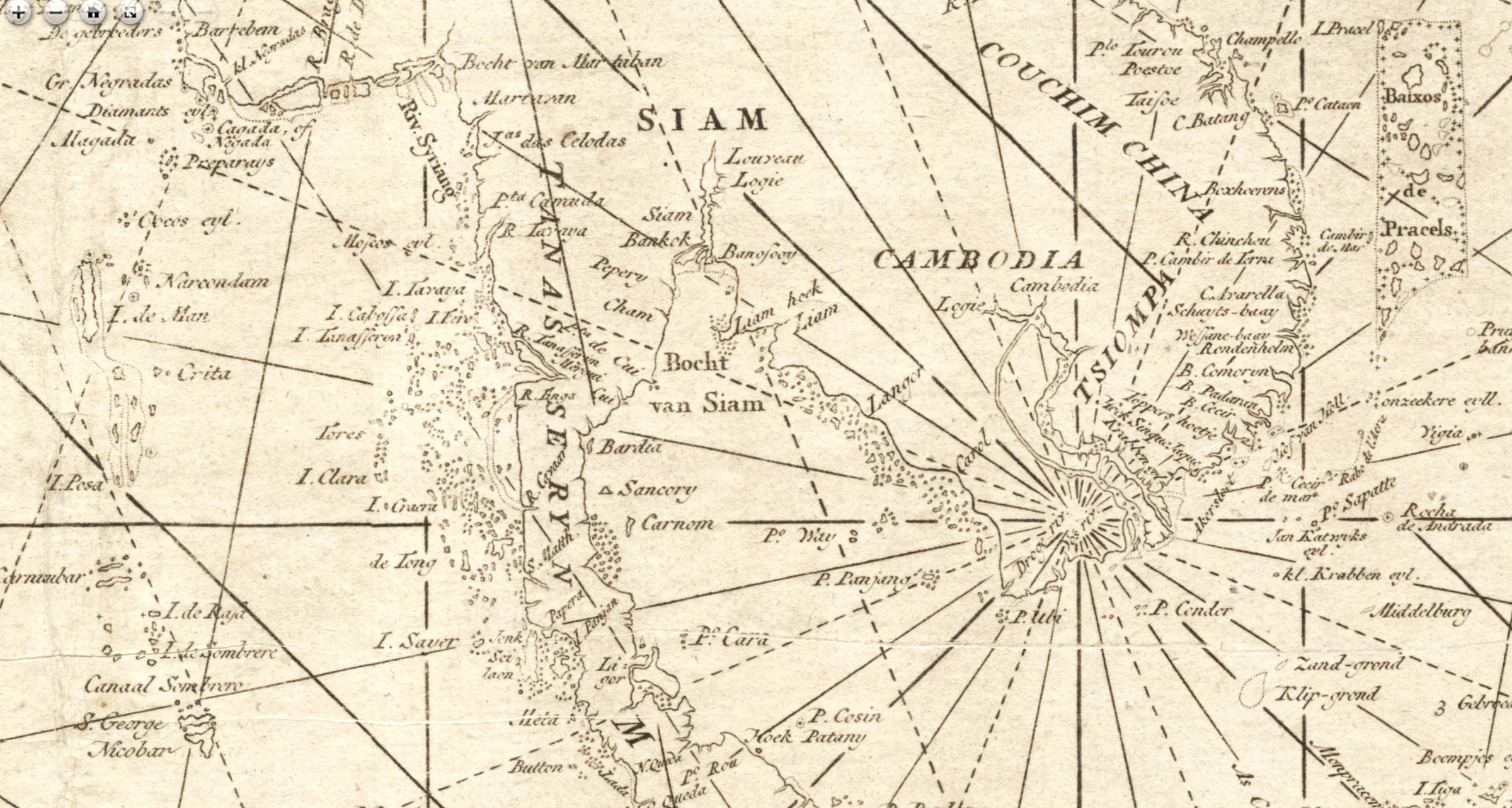

[ADB Input: Unsigned, these notes seem to have been penned by the editor-in-chief or the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, J.R. Logan, with the input of merchant and traveler Ludvig Verner Helms, and of Captain George D. Bonnyman [see the latter’s geographic notices on the southwestern coast of Cambodia here]. For geographical notations, they often refer to Oud en nieuw Oost-Indiën, vervattende een naaukeurige en uitvoerige verhandelinge van Nederlands mogentheyd in die gewesten, benevens eene wydlustige beschryvinge der Moluccos, Amboina, Banda, Timor, en Solor, Java en alle de eylanden onder dezelve landbestieringen behoorende het Nederlands comptoir op Suratte, en de levens der groote Mogols; als ook een keurlyke verhandeling van’t wezentlykste, dat men behoort te weten van Choromandel, Pegu, Arracan, Bengale, Mocha, Persien, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Malabar, Celebes of Macassar, China, Japan, Tayouan of Formosa, Tonkin, Cambodia, Siam, Borneo, Bali, Kaap der Goede Hoop en van Mauritius, by François Valentyn (1666−1727), published 1724 – 1726.]

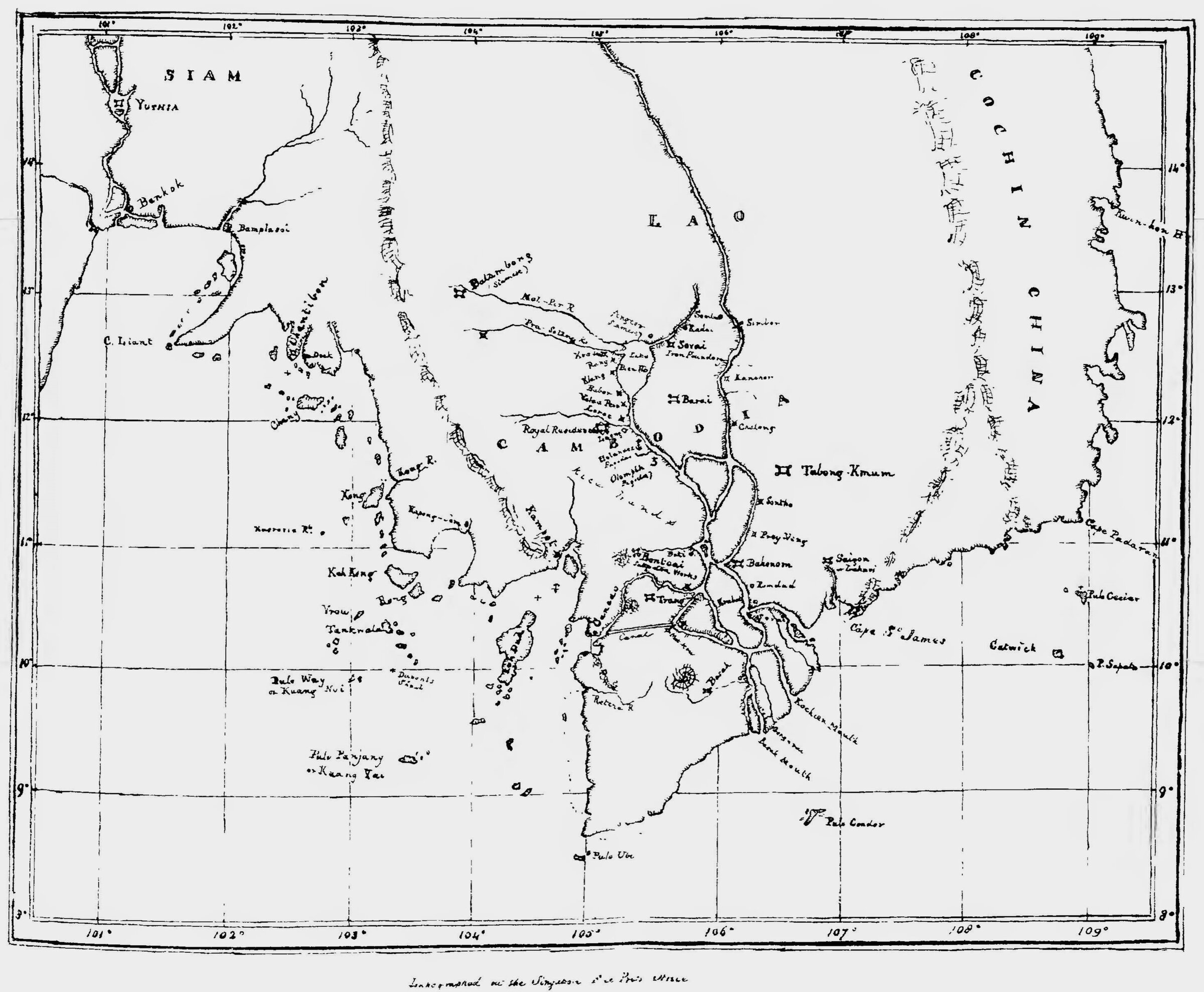

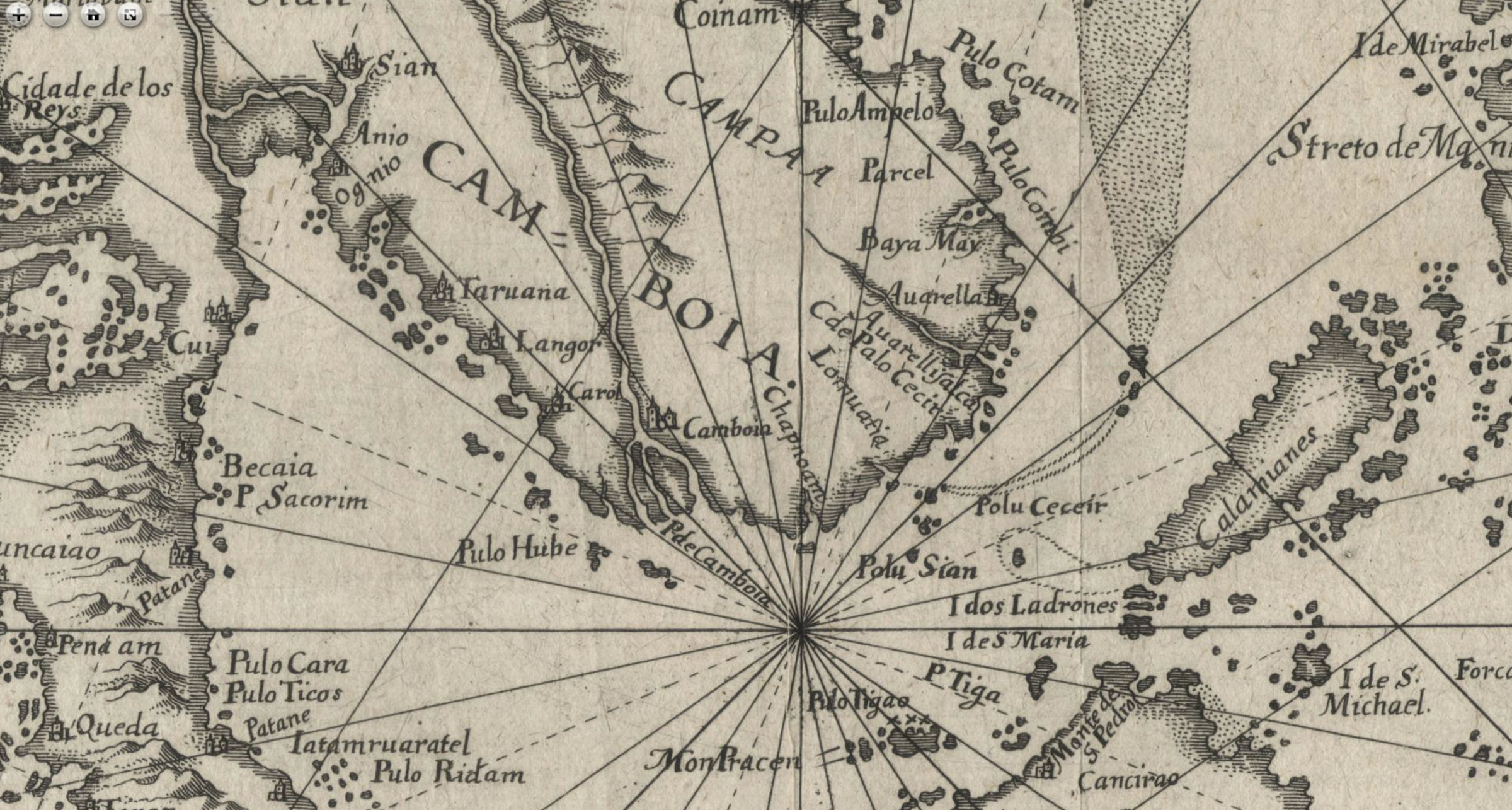

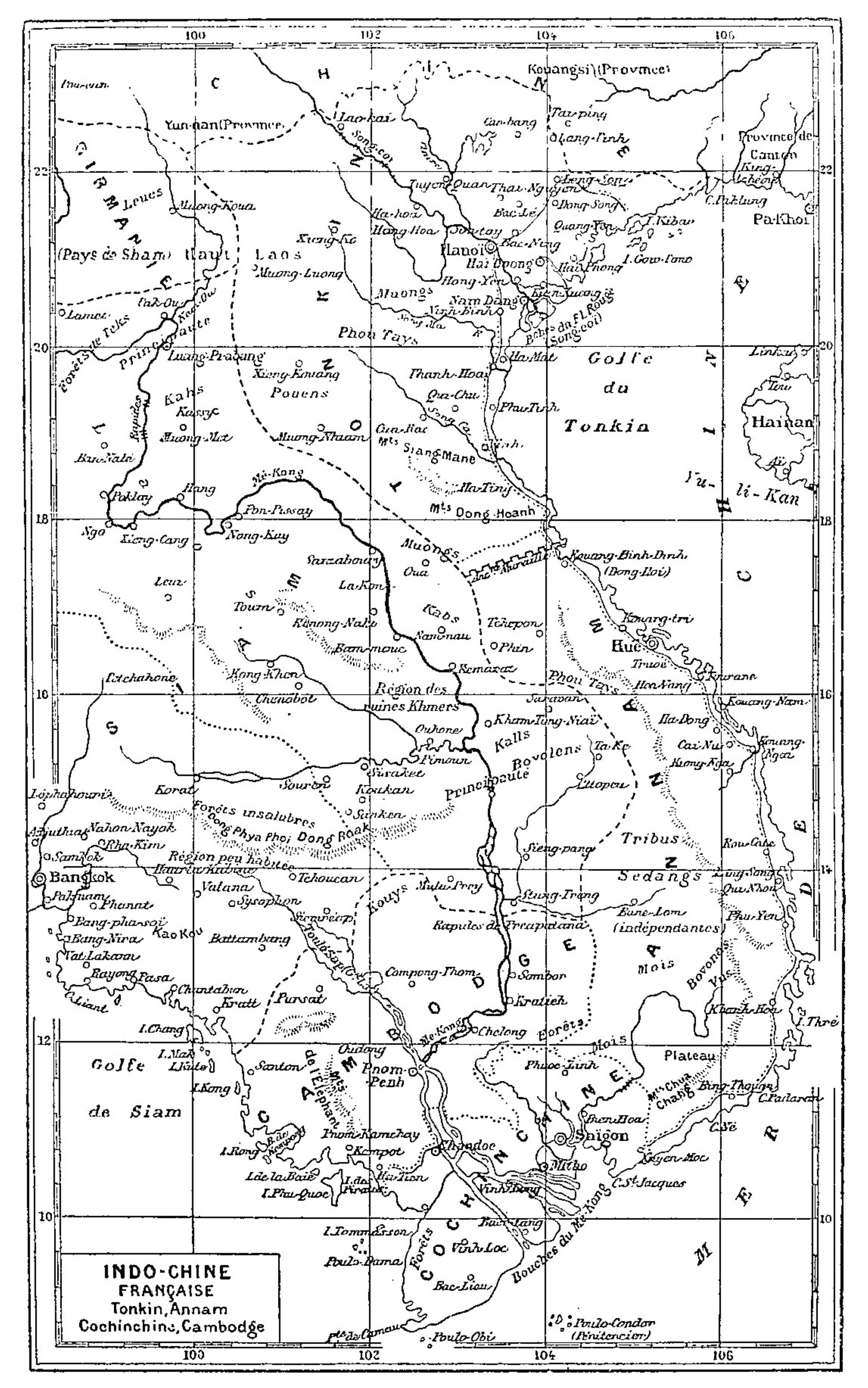

This map was compiled for the purpose of registering some items of geographical information obtained from Constantine Monteiro, a Native Christian in the service of the King of Cambodia, who was sent to this Settlement in July last, to solicit the aid of the authorities in ridding the Cambodian coasts of the pirates who infested them. The positions of many of the places in the interior of Cambodia may probably be incorrect, as they are not fixed by scientific observations, but in the total absence of all authentic information concerning that country, Mr Monteiro’s contribution must be considered as a valualde addition to our geographical knowledge of the Indo-Chinese Peninsula.

Coast Line

The eastern and south-eastern coast lines as far to the south as Cape St. James are laid down from the Admiralty Chart of the China Sea, published in 1840, and as the celebrated hydrographer Captain Ross, fixed the position of this cape, and the chain of longitudes has been carried to the various headlands along the coast of Cochin-China, this part of the peninsula is as well surveyed as most of the coasts of these eastern countries. But scientific research has gone no further, for throughout the entire remainder of the coast, from Cape St. James to Siam, an extent of between 500 and 600 miles, no single position has been fixed by a scientific observer. The position of the south point of Cambodia can be obtained with tolerable accuracy, as it lies only a quarter of a degree to the north of Pulo Ubi, an island well known from its being often seen by ships passing up the China Sea. The coastline from South Point of Cambodia to Chantibun [Chanthaburi] is laid down from a manuscript chart of unknown authority, which the masters of European trading vessels resorting to Kampot find to be much more accurate than the published charts. It was probably compiled from observations by commanders of East Indian country ships, which were in the habit of resorting to the Gulf of Siam some years ago. The only addition made in the accompanying map, is a reef to the north-east of Koh Dud, on which the English barque Sea Gull was wrecked during last year, shortly after leaving her anchorage at Kampot to return to Singapore. The portion of coast between Cape St. James and the South Point of Cambodia, including the western mouths of the Cambodia River (which have not been frequented by European ships for many years past) are laid down from the information of Constantine Monteiro, collated with the maps attached to Mr Crawfurd’s “Mission to Siam,” and to M. Abel-Remusat’s translation of a Chinese account of Cambodia in the 13th century.

Mountain Ranges

The peninsula is traversed by two parallel mountain ranges, running in a direction nearly N. N. W. and S. S. E. The western range terminates on the north side of the Kampot river, in Lat. 11“ S., but there are several isolated hills further to the south, of which the hill of Basak, near the centre of the delta formed by the embouchures of the Cambodia river, is the principal. This range is rich in metals, and furnishes a superior description of marble which takes a high polish, and is manufactured by means of turning lathes into vases and cups by the Siamese and Cambodians. The western base of this range abounds in teak timber, especially near Chantibon. The eastern range terminates between Cape St. James and Cape Padaran. It is less rich in metals than the western range, but many mines of silver and iron are worked by the Cochin-Chinese. These ranges form the natural boundaries of Cambodia to the East and West.

Rivers

The Me-kong is the single great river of Cambodia for, with the exception of a stream which disembogues at Kampot, it drains the entire basin formed between the mountain ranges mentioned above. The Me-kong is said to have its sources in the steppes of Chinese Tartary in Lat. 35“ in which case its length, in difference of latitude alone, must be 1,500 miles, and certainly the immense body of water poured out by this river during certain seasons shows that it must be the source of drainage to a large extent of country. The river has many mouths, all of which, with the exception of the Basak and Cancao channels, are navigable by vessels of burthen. The Cancao channel is a mere water-course as it is nearly dry during certain seasons of the year. About thirty years ago, the Cochin-Chinese, who had taken possession of the delta of the Me-kong, cut a canal from Cancao to a bend of the great river, to facilitate the transport of troops and munitions of war to the frontier of Siam, with which country they were then

at war; but it has since been filled up in parts during a panic caused by a rumoured invasion by the Siamese. The western branch of the main river is navigable by vessels of moderate burthen as far as the great lake. The country which bounds the river is uniformly level, and during the dry season, the banks are between 30 and 40 feet above the level ofthe stream, but during the freshes, the water rises enormously, and often overflows the country. At these times, so strong is the current that it becomes difiicult for a sailing vessel to ascend the river, even with the aid of a strong monsoon. During the dry season again the channel is impeded by sand-banks, and the quick-sands at the mouths of the river are constantly shifting, rendering the navigation peculiarly dangerous. These circumstances coupled with the misfortunes which have befallen Cambodia during the last century, have caused the once flourishing foreign trade to be abandoned. In 1850 a small vessel, the Scotia, belonging to an European merchant of Bankok, ascended the river to the capital of Cambodia, and was well received. The Siamese crew were imprisoned by the authorities on the return of the vessel to Bankok.

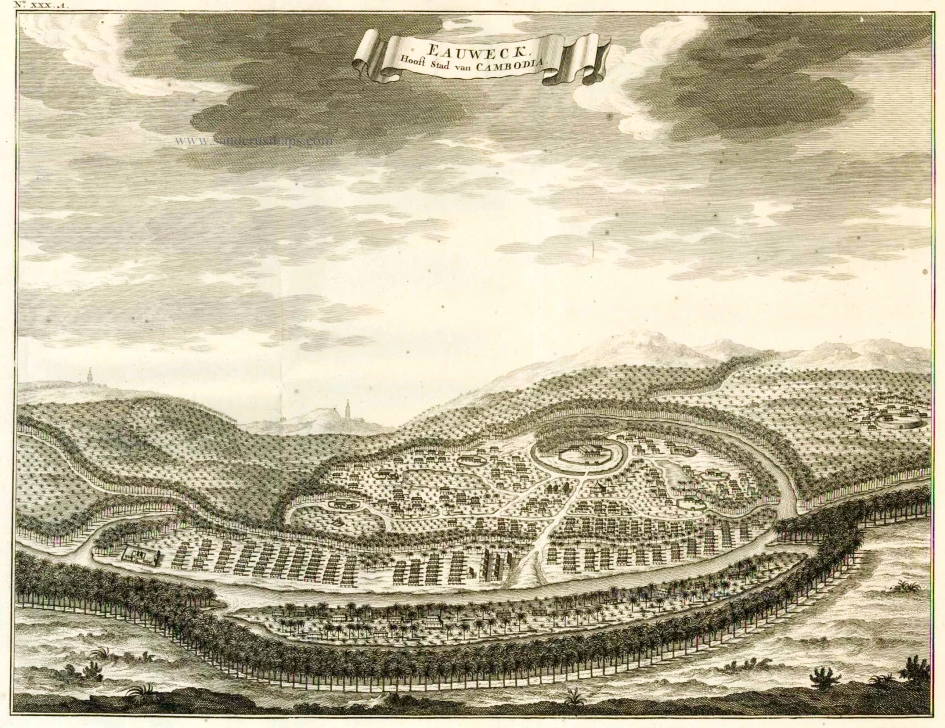

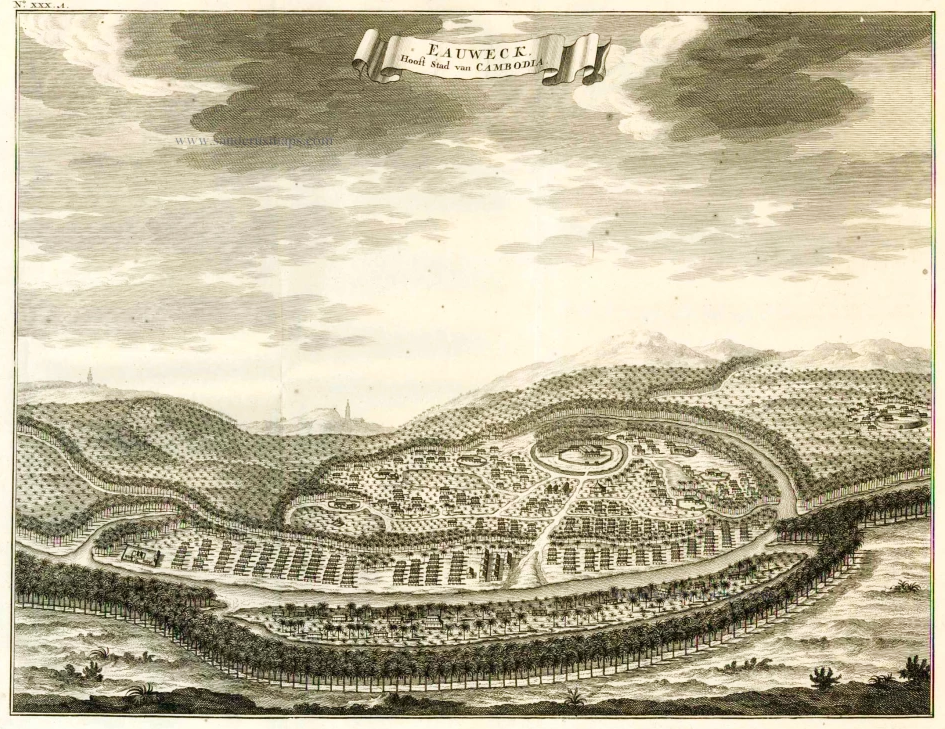

The geography of the upper portion of the Me-kong river is little known. In 1641, an agent or envoy from the Dutch factory then established in Cambodia, Gerard van Wusthoff, ascended the river to Winkjan, the capital of the Lao nation, which he estimated to be 2 – 50 Dutch or 1,000 English miles above Eauwek, the then capital of Cambodia. The ascent, which occupied 103 days, was much impeded by several water-falls and rapids, which rendered it necessary to unload the boats and cany them beyond the obstructions.

Ports and Harbours

The Coasts of the Indo-Chinese Peninsula abound in places affording shelter to shipping, that of Cochin-China being a constant succession of head-lands and inlets, and the islands which stud the shores of the Gulf of Siam render the western coast a complete series of harbours. The Cambodian portion of the coast consisting almost exclusively of the delta of the Me-kong, with its shelving alluvial banks and numerous quick-sands, is less safe to approach than other parts of the coast, although the mouths of the great river are excellent harbours when once a ship has succeeded in getting in safely. The Kochien mouth is the most easy of access for vessels of burthen, and was generally used by the Dutch, English and Portuguese vessels which traded with Cambodia during the 17th century. The easternmost mouth is the safest for vessels of moderate burthen, as there are fewer banks, and Cape St. James is a good mark for entering. The depth of water is less than in the Kochien channel. The Bassak mouth can only be entered by small vessels, but is said to be more frequented than all the others, as the town of Bassak has a large native trade, and the vessels of the Cliinese and Cochin-Chinese engaged in it are all of small burthen. Cancao or Ahtien, on the western side of the Cambodian delta, is an excellent port for vessels not drawing more than 18 feet water. The western embouchure of the Mekong enters the port, but it is only navigable, even by boats, during

the rainy season, and the canal that was cut by the Cochin-Chinese to afford communication at all times with the main river, has been blocked up. Nevertheless a considerable trade is carried on with Singapore in small junks and topes. Cancao [Can Tho?] has been for some years past in the possession of the Cochin-Chinese. Pontaimas [1], formerly the emporium of Western Cambodia, was situated on the south side of the harbour. It was destroyed during an invasion of the Siamese about a century ago. Kampot, the only port now remaining in the actual possession of the Cambodians, lies about 25 miles to the north of Cancao. The anchorage is good at all seasons, about 5 miles S. S. W. from the western entrance of the river, in 3 fathoms, and deeper water may be obtained by borrowing on Koh Dud [2], an island occupied by Cochin-Chinese, who dwell at peace with the Cambodians except when urged to agression

by their government. The trade with this port is chiefly carried on in square-rigged vessels of about 200 tons burthen,

owned or chartered by Chinese merchants residing here. Small as the trade is, it forms the sum total of commercial intercourse carried on between this port and the Indo-Chinese Peninsula in European vessels.

Towns and Provinces

Cambodia seems never to have had a fixed capital, the different kings selecting the spot for their residence which best suited their taste or circumstances, after the Tartar fashion. This accounts for the confusion that exists respecting the name of the capital of Cambodia, no two original maps including the Me-kong river that the writer has had opportunity of inspecting, agreeing in this particular. Only two of these, indeed, appear to have been compiled from authentic information ; that attached to Valentyn’s “Oost Indien” published in 1726, and a modem map of the river Basins of Europe and Asia by Professor Berghaus of Berlin.

During the period in which the Dutch maintained a factory in Cambodia from 1635 to 1672, Eauwek [Longvek or Lovek], stated to be 60 Dutch miles up the river, was the capital. This is probably the spot indicated by Monteiro as “Holandez.” A sketch of Eauwek is given in Valentyn’s work, from which it appeare that the buildings were composed of no more durable materials than wood and attap, which could be removed to another spot in the course of a few days. The present residence of the king is situated on the banks of a tributary which joins one of the branches of the Mekong a little to the south of the Lake Bein Ho (The name and position of this lake, as given by Monteiro, perfectly accord

with those laid down in Berghaus’ map of the River Basins.) A hostile demonstraiion on the part of Siam would probably induce the king to remove nearer to Cochin-China, but if both pressed him, he would have no other resource than to take refuge for a time among the Lao of the north.

Olompeh, a city of Pagodas and Royal tombs, occupied by Buddhist priests and their dependants, is the real capital of Cambodia, as all the inhabitants of the country who are sufficiently wealthy to travel, take up their residence there periodically, to offer up prayer and sacrifices and perform funereal ceremonies. This is probably the city called “Columpe” in Valentyn’s map, and “Penomping” in that of M. Abel-Remusat. The banks of the river between this and the lake are very densely inhabited, the people living chiefly in towns strewed along the banks of the river, which each contain from 500 to 2,000 adult males, wbo are registered as soldiers, and nearly the same number

of Talapoins or priests. This part of Cambodia, and the country extending along the base of the range towards Kampot, is the only portion of the territory that can be called independent at the present moment.

Batambong, (formerly called Kutambong) the capital of the country producing cardamuins, a valuable description of spice, is in possession of the Siamese, who have also an establishment at Angcor, a sacred city on the north shore of the lake. The entire left bank of the Me-kong, from Simbor to the sea, is under the influence, if not in the actual possession, of the Cochin-Chinese. Bahonom (the Bilhanon of Valentyn) is the most important city on this side of the river.

Kampot, the solitary sea-port town at present in the possession of the King of Cambodia, is a small place, occupied chiefly by traders, and governed by a civil functionary who has a small body of troops at his disposal. Communication is kept up with the chief city by a road which lies over low and level land, that in times of peace, is cultivated for rice. This product from the vicinity of Kampot forms the bulk of the return cargoes of vessels from Singapore, which are filled up with wax, cardamums, raw silk, benjoin, gamboge, and other less bulky articles, which are brought from the interior on the backs of elephants. It is said that the lands already brought under cultivation on the banks of the Mekong could supply the entire Archipelago with rice, and that the present population would suffice to cultivate it, but a free water carriage to the sea, and ample protection for the agriculturists, would be necessary before these advantages could be fully availed of.

Basak, the southernmost Province of Cambodia, is one of the most productive, from the facilities afforded for exchange with foreign traders. When this province was under the King of Cambodia, the annual tribute amounted to 10,000 koyans (about 20,000 tons) of rice, and as many of salt and now that it is ruled by the Cochin-Chinese it is probably not much less. The agricultural population is exclusively composed of Cambodians, but there is also a large floating population of Cochin-Chinese, who are chiefly occupied in fishing, in which they are very expert, and the

neighbouring waters afford them an abundant harvest.

[Although not drawn by professional geographers, this map is definitely more accurate than all those previously attempted by Western cartographers, a turning point in the history of cartography for Cambodia. True to the Cambodian practice at the time, provinces rather than villages are shown (from North to South Barai, Simbor (Sambor), Tabong Kmum (Tbong Kmum), Babor (Kompong Chhnang), Prey Veng, Bahnom (Ba Phnom), Svai Téep, Bati, Romduol, Koh Kong, Cancao, the new port of Kampot, while Battambang and Angkor are marked as ‘Siamese’ (Siamese annexion ended in 1904). The Tonle Sap Lake is referred to by his Vietnamese name, Lake Bien Ho (Biển Hồ,“as big as the sea”). Note the prominent “canal” shown south of ‘Trong’ [?].]

Outline of History

The Cambodians are probably, in common with the other nations distinguished by the appellation of Indo-Chinese, an off-shoot from the great Lao nation which occupies the upper basin of the Mekong and other large rivers which have their sources in Tibet. According to Chinese records, Cambodia commenced sending ambassadors and tribute to the rulers of China in A. D. 616, but as no conquest is spoken of, this probably means that a commercial

intercourse commenced between the two nations during that year, when the smaller powers would naturally send presents to the larger. Cambodia soon became the greatest nation of the Indo-Chinese peninsula, if it was not so before, and according to the records of the Ming dynasty, Cochin-China was annexed, and incorporated with the Cambodian empire about A. D. 1200.

Siam seems also to have been under the yoke of Cambodia previous to A. D. 1351, when the Siamese records commence. (Chinese Repository vol. v. p. 56). In the early part of the 16th century, European influences came into play. The Portuguese opened an intercourse with Siam, Cambodia and Tonkin soon after their arrival in the east, and the English and Dutch followed.

Cambodia was eventually disgusted with the quarrels which took place between the Portuguese and the Dutch, which often led to bloodshed, and in 1672 the factory of the latter was withdrawn. In the mean time Siam and Cochin-China, the weaker powers, encouraged intercourse with Europeans, especially the French, whose military tastes and abilities rendered them apt instructors in the art of war. French influence soon became paramount in

Cochin-China, where the people were taught to construct fortifications, cast cannon, and to use the musket with effect. As a military nation is not calculated to attract commerce, they were not disturbed by other Europeans; but in Siam, where the Dutch had established a factory many years previous to the arrival of the French, the influence of the latter did not become paramount, although it has always been great. The Siamese proved apt scholars in the art of war, but never arrived at an equality upon this point with the Cochin-Chinese. The results to Cambodia were inevitable. Deprived by its own exclusiveness of that intercourse with Europeans which would have familiarised it with the improvements of the age, the territory on either hand has been annexed by its more warlike neighbours, and the small remnant owes its preservation solely to the jealousy of the rival invaders, who have at length met in the course of conquest, and turned their forces against each other.

ADB Input: The Enigmatic Toponymy of pre-Modern Cambodia

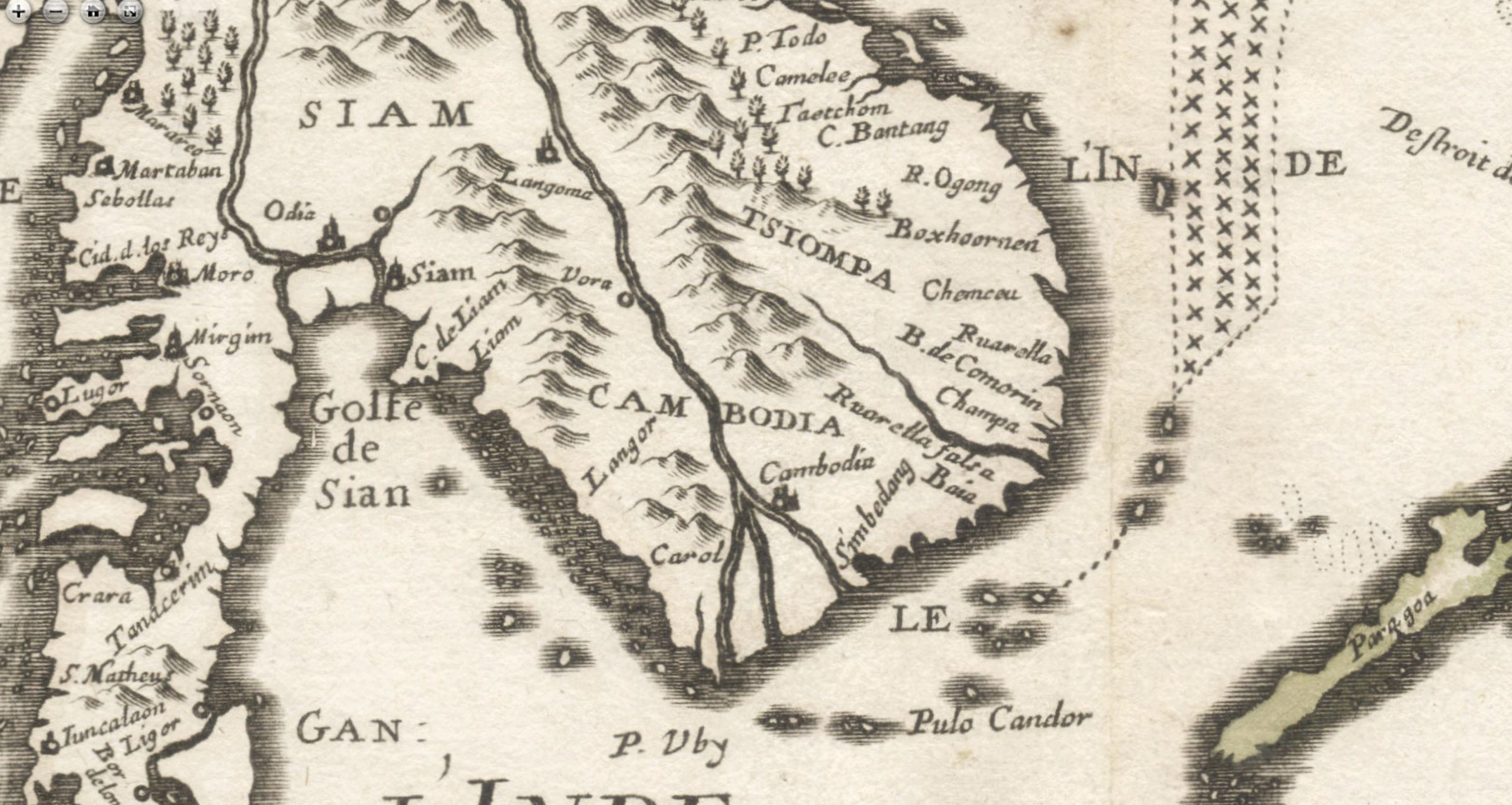

From Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485−1557), who published a map of the area in his Delle Navigationi et Viaggi (Venice, 1563) to the Francois Valentijn’s map above in 1726, and even later, several toponyms associated to Cambodia remain unexplained, in particular:

- Langor, shown south of Cape Liam (or Liant, or Lion) on the coast, and Carol (Coroll, Coxal, Caxol, Corol): Aymonier, in ‘Identification des noms de lieux portes sur les cartes de M. Marcel’ (Bulletin de geographie historique et descriptive,1905, pp 43 – 4), wrote:

“Je crois que ces termes plus ou moins altérés représentent le cambodgien Koh Trâl, nom que les Khmers donnent à la grande île que les Annamites appellent Phu-Quoc. Les premiers cartographes ont pu souder cette île au continent, mais ils ont connu son nom indigène Koh Trâl, “île de la navette”. Au nord-ouest de ce point, ces cartes indiquent généralement une ville de Langor, qui est située non loin du littoral. Je crois qu’il s’agit d’Angkor, que les voyageurs devaient connaître de reputation. Sous celle forme, Langor, ce nom apparaît pour la première fois, sauf erreur, sur la carte n° V (i58o) et les cartes suivantes le reproduisent jusqu’au milieu du 18eme siecle. Langor semble bien être la corruption du siamois Lokhon ou du Khmer Angkor. Quant au déplacement vers la mer de la vieille capitale du Cambodge, il né constitue pas une objection sérieuse, car on sait combien la précision laisse à désirer en tous ces anciens documents.””[I believe these more or less altered terms represent Cambodian Koh Trâl, the name that the Khmers give to the large island that the Annamites call Phu-Quoc. The first cartographers may have welded this island to the continent, but they knew of its native name, Koh Trâl, “shuttle island”. To the northwest of this point, these maps generally indicate a town of Langor, which is located not far from the coastline. travelers must have known by reputation, Langor, this name appears for the first time, unless I am mistaken, on map No. V (i580o and the following maps reproduce it until the middle of the 18th century Langor seems to be the corruption of the Siamese Lokhon or the Khmer Angkor. As for the movement towards the sea ofthe old capital of Cambodia, it does not constitute a serious objection, because we know how much the precision leaves to be desired in all these ancient documents.” [This interpretation of “Langor” has been contested by B.P. Groslier and G. Coedès — who thought it must have been a derivative of Thai ‘Nakhon’, capital city -, and we’ll add to their remarks 1) that Angkor was known to the early cartographers, mostly Spanish, Portuguese, or Italian, as ‘Angon’. 2) there was no reason for Western navigators to go to landlocked Angkor, but Langor does not sound far from Langoma, considered here below. 3) would it be possible that early navigators misplaced Selangor, a port active on the other side of the Malay Peninsula, inside the Gulf of Siam?] - Langoma (or Jangoma, Tangoma, Tarvana, Tanano, Tarrana) [ shown either on the coast between Cape Liam (Liant) and Langor, either on the Mekong River, roughly at the location of Phnom Penh: Aymonier, again, was in the opinion that both toponyms Vora and Langoma represented the city of Korat, “dont le nom complet est

Angkorréach Sema, soit, par abréviation et corruption, Langor-ma ou Langoma, plus tard remplace par Corazema ou Corazona.” - Olompeh (or Colompé, Colompié) was the name used by Western cartographers — and even on the map here discussed, dated 1851 — for Phnom Penh. Historian Mak Phoeun noted in his Histoire du Cambodge… that “Le Père Louis Chevreul, venant de l’embouchure du Tonlé Thom (Mékong), arriva à Colompé (Phnom-Penh) le 21 novembre 1665. Au début de 1670, les Portugais se saisirent de lui et l’expédièrent par bateau à Macao, puis de là à Goa, “sous l’inculpation d’hérésie””. Note on the map above how Longvek, ‘the Royal Residence’, ‘Holandez’, Olompeh (Pagoda), Lueng (Kompong Luong) are closely knitted together, and how close they seem to the Great Lake, while Oudong is shown in another area altogether. [The origin of Spanish Colompe has never been clarified. ‘Colompiar’ in Spanish means ‘take a jump or jump backwards’. Could that refer to the spectacular flow reversal of the Tonle Sap River at the end of the monsoon season?]

- Simmeding (or Semding) River, a river linking the Mekong River to the Bassac River in the Delta. Antoine Cabaton, working on Dutch sources about Cambodia, identified: ” 1) Bassac River or Hau River (Chau Doc River, Tonle Kroi in Khmer, Hau Giang in Anmam), also called “Japanese River” because there was a community of Japanese Christians who were driven out of their homeland because of their religion, and settled on the right bank of the Mekong River, near Phnom Penh. 2) Cambodia River, a branch of the Mekong River, called Tien River (or Banam River or My Tho River, Tonlé Mŭk in Khmer, Tien Giang in Annam) 3) Matsian River and Simmeding River, probably other rivers, branches or names of mouths of the Mekong River.”

- Cape St James: According to B.P. Groslier and C.R. Boxer, ‘Saint Jacques’ could be a homophonic adaptation of the Portuguese Cincas Chagas (for the five hills there visible), in use since at least 1595, probably the Promontorium Notium as identified by Ptolemy.

Francois Valentijn (Valentyn) Reporting Admiral Jacob van Neck’s fleet “ill-treated” in Cambodia, September 1601

If the Book III of Valentijn’s gigantic Oud en nieuw Oost-Indiën (1724−6) [3] has been perused over by historians of Cambodia, we stumbled upon a mention of “incidents” on the Cambodian coast in 1601, during the third Dutch Expedition to the Indies). For background, Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck (1564−8 March 1638) had led a second commercial expedition from May 1598 to July 1599, bringing back to Amsterdam an impressive cargo of spices and goods from Padani, Molucco Islands and Madagscar on the fleet’s eight ships. This commercial prowess (or plundering) led to the establishment in March 1602 of the United East India Company [Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC] with a 21-year monopoly to carry out trade activities in Asia.

The following short relation appears in Eerste Boke (Book I), p 172,180:

[Chapter headlines:] Jacob van Neks tweede tocht in’t jaar 1600. Verzeilt naar China en Patani. Van waar hy na’rt vaderland keert met twee fchepen. Wedervaaren van drie van zyn andere fchepen. Die in Cambodia niet wel gehandelt wierden. Haar komft in Patani.[…] [Jacob van Nek’s second journey in the year 1600. Arrives in China and Patani. From where he returns to homeland with two ships. Experiences of three of his other ships. They are not properly treated in Cambodia.

Zy leden daar na nog groote armoede en elende, zoo dat Gouda cindelyk zyn topftander, ten Wat de fchepen Dordrecht, Haarlem en Leyden, mede van de heer van Neks vloot, by Annabon door hem gelaaten, betreft, deze quamen den 9 Augusti andere fchepen, 1601. voor Bantam op de reede, daar zy ‘t fchip Hollandia, en ‘t jagt het Duifken vonden leggen. Zy bleven daar 11 dagen, wanneer zy na China zeilden, en den 10den September voor Cambodia ten anker quamen, alwaar zy niet wel gehandelt wierden, en men in Januarii 1602. 12 man van ‘t fchip Haarlem, en 11 van ‘t fchip Leyden, nevens hunnen zeevoogt en koopman, gevangen nam; die daarna vry gekogt wierden voor twee metalen stukken geſchut.

Na daar nog eenige fchermutzelingen met de Inlanders gehad, en een dorp verbrand te hebben, liepen zy den 21 December van daar, en quamen den 28ften dito voor Patani ten anker, daar zy den 10 Julii 1603. nog 2 Hollandsche fchpen by zich kregen. Zy vertrokken den 24dten September met de fchepen Leyden en Dordrecht, volladen met peper.

As regards the ships Dordrecht, Haarlem and Leyden, also from Lord van Nek’s fleet, left by him at Annabon on August 9, 1601, they went to Bantam, where the ship Hollandia, was mooring. They stayed there for 11 days, then sailed to China, and on 10 September came to anchor off Cambodia, where they were not treated well, and in January 1602 [?], 12 men from the ship Haarlem, and 11 from the ship Leyden, together with their sea captains and merchants, were captured, and released in exchange of two metal bars.

After having had some skirmishes with the Natives there, and having burned a village, they walked from there on December 21, and anchored off Patani on the 28th, where on July 10, 1603, they received two more Dutch ships. They left on the 24th of September with the ships Leyden and Dordrecht, loaded with pepper.

We are looking for more information on this incident.

Critic of the Map of Cambodia 1851 in Mgr Miche Letter to JIAEA, 1852

[One year later, in 1852 (JIAEA, Vol. VI), the same journal published a letter from J.C. Miche, a French bishop active in Cambodia since the 1830s, criticizing the toponymy and geography of the 1851 map (“more of a sketch than a map”, conceded the editor). The leter opens with a harsh rebuff of this “little map of Cambodia, recently lithographed at Singapore under your direction, after the information of a certain Mr Monteiro, who has the defect of speaking with equal assurance on subjects with which he is, and is not acquainted.” After arguing about Sombor-Somboc, north of the Mekong, “which I personally visited in 1849”, the irate bishop made the following, often pertinent remarks:]

- Bontiai, (this is a Cambodian word signifying “town” but the true Cambodian name is Penompeuk, the Cochin Chinese call it Namvang) is placed in your map far inland to the west of Bati. There is no truth in this. This Bontiai or Penompeuk is situated at the point where the river which descends from the great lake joins the main stream. Bati, on the contrary, is to the south, and lies inland. It is impossible to find a position more beautiful or more advantageously situated as a place of commerce than that which is occupied by the city of Penompeuk. To the north it communicates with Laos by the Mecon; and to the northwest it has access to all the provinces of Cambodia proper, as well as to those which are subject to Siam, by the river which traverses the Great Lakt. To the south, the two rivers before mentioned which unite at Penompeuk, afterwards subdivide into two distinct branches, which open out an easy channel for commercial operations with the whole of lower Cochin China and the Delta of Ancient Cambodia.

- There is actually a canal from the port of Hatien, (designated in your map by the name of Cancao, which is further to the south) to Mot Kl’uk, a Cambodian name, which has been replaced by that of Chau Doc by the Cochin Chinese: it is now the capital of the province of Angiang. This canal is the only passage by which the river which descends from Penompeuk can be reached from Hatien, and consequently the pretended river, the course of which is indicated to the north of the canal, and which disembogues at Hatien, has no existence. The said canal is situated within the Cochin Chinese territories, and as the Cambodians are not allowed the right of passage through it, all commerce with the exterior is impossible.

- In the explanatory notes which accompany the chart of Cambodia, the port of Cochien [related to the Sông Cổ Chiên, Co Chien River in modern Vietnam?] is briefly spoken of, which is described as a pretty good anchorage. This might have been the case formerly, but now, if a little schooner of 25 or 30 tons were to set out with these incorrect data, for the purpose of resorting to Cochien, she would infallibly be wrecked, as the road is filled vvith sand, which is incessantly brought down by the great river of Laos, so much so that even the small vessels of the Cochin Chinese do not venture there. They have also removed the Custom House which was established there, owing to its having become useless.

- I will not expatiate here on the respective distances in latitude and longitude between the different cities laid down in your chart, in which as many errors could be pointed out as there are places, but were I to attempt to correct these errors, I should expose myself to commit others ; as in this matter, to be exact, it is necessary

to be provided with the instruments which science places in the hands of geographers, for without these, the traveller can only give approximative positions. But Mr Monteiro has not given you even approximative positions, of which it will suffice to give you only one example, which I take by chance. In the map he places the Royal Residence in the same latitude with Chalong [Chhlong, Kratie Province], which is situated on the left bank of the great river. There is so little truth in this, that one reaches Penompeuk from the Royal

Residence in 5 hours, while the journey from Chalong to Penompeuk occupies 4 or 5 days, yet the direction of these places with reference to each other is such that the difference of longitude made is not greater on proceeding to one than to the other. - [Commenting Mgr Miche’s acerbic comments, the JIAEA editor cautiously remarked that “Monseigneur Miche’s corrections which are confined to the Cochin Chinese portion of the Peninsula, are probably founded on better data. But on the other hand, Mr Helms, who visited the Royal Residence in the course of last year, and a narrative of whose journey appeared in the number of this Journal for July last (Vol. V. p. 434) found that its position in the map was correct, and that Mr Monteiro’s sources of information were of the best description.” The editor also quoted large excerpts from Miche’s 1849 travelogue to Northeast Cambodia [Letter to the Annales de la Propagation de la Foi, March 1851], in which we can find this kind of not too scientific remarks: “As to morality [of women and men], it would be difficult to speak correctly upon the point without a more extended acquaintance with them. On this head, nevertheless, I may remark that their habitual wretchedness, their manner of living and above all the absence of all religious principle, ought to make these wild people very corrupt. It appeared to me from the conversation I had with them that they were not addicted to a single kind of superstition, a thing difficult of believe.”

Oudong in Mak Phoeun’s Histoire du Cambodge du XVIeme au XVIIeme siecles, pp 238 – 9

En ce qui concerne la position d’Oudong, appelée par les Européens Camboie, Cambodia — ou même Eauweck (Lovêk ou Longvêk), du nom de l’ancienne capitale sans doute rattachée à la nouvelle ville — on nous dit qu’elle était située à environ 60 lieues de la mer, en remontant la rivière. Pour la mettre à l’abri des débordements de ce fleuve, on l’avait bâtie sur une digue qui en constituait l’unique rue, le long de laquelle se pressaient de nombreuses maisons contiguës. Outré des Khmers, la ville était habitée par des étrangers installés soit à demeure, soit temporairement au Cambodge. Ces étrangers faisaient du commerce et vivaient regroupés par nations dans des quartiers qui leur étaient spécialement réservés. En dehors de cette capitale, Hendrik Hagenaar fait état d’une seule autre ville, le bourg de Phnom-Penh, où « une assez belle tour dorée » se voit à partir du fleuve. Jean-Albert de Mandelslo, lui, fait état de cinq villes : Tarvana, Langor, Carol, Leweck (Longvêk) et Cambodia (Oudong), qui auraient été considérées comme « les plus considérables» du royaume.

C’est naturellement par le Tonlé Thom ou Mékong que les Hollandais et les autres étrangers se rendaient à Oudong. Après avoir longé, le 9 mai 1637, la côte cambodgienne, l’escadre placée sous les ordres de l’amiral Hendrik Hagenaar entra dans la Rivière du Cambodge (Mékong ou Tonlé Thom) — peut-être par l’embouchure du ‘Baralhao China’ que l’on né sait pas situer avec exactitude — par un chenal, mais avec beaucoup de difficultés, à cause des bancs de sable. Ce né fut vers le soir du 15 mai qu’elle se trouva vraiment en état de naviguer sur le fleuve. Le jour suivant, elle parvint à la rivière de Matsiam dont l’entrée était étroite mais dont les deux rives étaient pourvues de beaux arbres. À la faveur du vent, elle arriva, après avoir dépassé quelques îles, à l’embouchure de la petite rivière de Simmeding où les « vaisseaux furent couverts d’une si prodigieuse quantité de Mosquites, qui sont une sorte de moucherons […] qu’à-peine les chandelles pouvoient-elles demeurer allumées, & ils nous firent beaucoup de mal ». Ce né fut que le 23 mai, après maintes difficultés — dues aux bancs de sable et au fait qu’en certains endroits la largeur du fleuve n’atteignait que deux ou trois fois la longueur d’un vaisseau — que l’escadre parvint à l’endroit où le fleuve devenait plus large, celui à partir duquel on commençait à l’appeler la Rivière du Japon (ou Rivière Japonaise). De nombreux bâtiments y naviguaient et sur ses rives paissaient plusieurs troupeaux de buffles. La navigation devenant plus aisée, l’escadre navigua mieux. Le 28 mai, un dignitaire délégué par l’ubhayorāj khmer vint à la rencontre de l’ambassadeur de la VOC. Le 10 juin, l’escadre arriva à la pointe de la Rivière Japonaise. Le 11, elle fut en vue de la « rivière de Lau » dont le courant était très fort. Après avoir dépassé « les bancs & et l’embouchure de la riviére de Matsiam », elle réussit, avec un vent favorable, à gagner rapidement, malgré les courants, le bourg de « Buomping [Bnomping/Phnom-Penh] », puis de là, le lendemain, la loge de la compagnie hollandaise (le 11 juin).

En ce qui concerne le pays lui-même, les Hollandais écrivent qu’il était fertile et possédait une grande quantité de criques, de rivières, d’eaux courantes et d’eaux dormantes. Un grand lac (le Grand Lac ou Tonlé Sap) déversait une grande quantité d’eau non seulement dans la Rivière du Japon (ou Fleuve Antérieur) qui était assez

large, mais aussi dans les rivières de Matsiam (le Bassac) et « de Camboi » (ici le Mékong pour sa partie supérieure ou « Tonlé Thom amont »), qui parfois né pouvaient les contenir. D’où, au mois d’août, l’inondation des terres riveraines qui étaient entièrement recouvertes. Les vivres y étaient abondants et à des prix très raisonnables. La présence d’étrangers de nationalités diverses, comme le trafic important sur le Tonlé Thom, témoignaient d’une grande activité commerciale. Les Portugais importaient des étoffes de Malacca et exportaient du benjoin, de la laque, de la cire, du riz, ainsi que des produits provenant d’autres pays (cuivre, fer de Chine). Chaque année, rien qu’à destination du Quinam (Cochinchine), le Cambodge exportait plus de 2 000 coyangs de riz.

“Regarding the position of Oudong, called by Europeans Camboie, Cambodia — or even Eauweck (Lovêk or Longvêk), from the name of the old capital undoubtedly attached to the new city — we are told that it was located about 60 leagues from the sea, going up the river. To protect it from the overflow of this river, it was built on a dike which constituted the only street, along which numerous adjoining houses were crowded. In addition to Khmers, the city was inhabited by foreigners living either permanently or temporarily in Cambodia [4]. These foreigners traded and lived grouped by nations in neighborhoods specially reserved for them. Outside of this capital, Hendrik Hagenaar mentions only one other city, the town of Phnom Penh, where “a rather beautiful golden tower” can be seen from the river. Jean-Albert de Mandelslo mentions five cities: Tarvana, Langor, Carol, Leweck (Longvêk) and Cambodia (Oudong), which would have been considered “the most considerable” in the kingdom.

It was naturally by the Tonlé Thom or Mekong that the Dutch and other foreigners went to Oudong. After having skirted the Cambodian coast on May 9, 1637, the squadron placed under the orders of Admiral Hendrik Hagenaar entered the Cambodia River (Mekong or Tonlé Thom) — perhaps through the mouth of the ‘Baralhao China ’ which we do not know how to locate with precision — by a channel, but with great difficulty, because of the sandbanks. It was not towards the evening of May 15 that she found herself truly able to navigate the river. The following day, she reached the Matsiam river, the entrance to which was narrow but whose two banks were provided with beautiful trees. With the help of the wind, she arrived, after passing a few islands, at the mouth of the small Simmeding river where the “vessels were covered with such a prodigious quantity of Mosquites, which are a kind of midges […] ] that the candles could barely stay lit, and they did us a lot of harm. It was only on May 23, after many difficulties — due to sandbanks and the fact that in certain places the width of the river was only two or three times the length of a vessel — that the squadron managed to the place where the river became wider, the one from which it began to be called the River of Japan (or Japanese River). Many ships sailed there and several herds of buffalo grazed on its banks. As navigation became easier, the squadron sailed better. On May 28, a dignitary delegated by the Khmer ubhayorāj came to meet the VOC [Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie] ambassador. On June 10, the squadron arrived at the tip of the Japanese River. On the 11th, she was in sight of the “Lau River” whose current was very strong. After passing “the banks and the mouth of the Matsiam river”, she managed, with a favorable wind, to quickly reach, despite the currents, the town of “Buomping [Bnomping/Phnom-Penh]”, then there, the next day, the lodge of the Dutch company (June 11).

Regarding the country itself, the Dutch write that it was fertile and had a large quantity of creeks, rivers, running waters and still waters. A large lake (the Great Lake or Tonlé Sap) discharged a large quantity of water not only into the Japan River (or Anterior River) which was quite wide, but also in the rivers of Matsiam (the Bassac) and “de Camboi” (here the Mekong for its upper part or “Tonlé Thom upstream”), which sometimes could not contain them. Hence, in August, the flooding of the riverside lands which were completely covered. Food there was abundant and at very reasonable prices. The presence of foreigners of various nationalities, like the significant traffic on the Tonlé Thom, testified to great commercial activity. The Portuguese imported fabrics from Malacca and exported benzoin, lacquer, wax, rice, as well as products from other countries (copper, iron from China). Every year, to Quinam (Cochinchina) alone, Cambodia exported more than 2,000 coyangs of rice.

[1] Pontiamas and Cancao are names used by geographers of the time to refer to the Principality of Hà Tiên (ch 河僊鎮, th เมืองพุทไธมาศ Mueang Phutthai Mat), an independent entity formed by Chinese settlers subdued by the Siamese Rattanakosin Kingdom, and annexed by the Vietnamese Nguyễn dynasty in 1832. It was called Phutthaimat (พุทไธมาศ) or Banthaimat (บันทายมาศ) in Thai, Ponthiamas, Pontiamas, Pontiano, Cancao or Cancar by Western travelers, and Banteay Meas (បន្ទាយមាស) in modern Khmer.

[2] Koh Dud was the Siamese name of the island of Koh Tral (Cambodia), to become Phú Quốc, now in Vietnam. The island of Koh Kong កោះកុង was called Patchan Khiri Khet under Siamese administration (until 1904).

[3] Published by Johannes van Braam and Gerard Onder de Linden, Dordrecht and Amsterdam, 1724.

[4] That would explain why Constantin 7de Monteiro indicated a village called Holandez.

note: burthen is the Older English word for burden, weight, weight down, load.

Tags: geography, Modern Cambodia, maps & plans, King Ang Duong, Lovek, Phnom Penh, Tonle Sap Lake, Kampot, toponymy, canals, pre-modern Cambodia, Angon, Oudong, Vietnam, Kampuchea Krom

About the Author

Angkor Database

Angkor Database — មូលដ្ឋានទិន្នន័យអង្គរ — 吴哥数据库

All you want to know about Angkor and the Ancient Khmer civilization, how it keeps attracting worldwide attention and permeates modern Cambodia.

Indexed and reviewed books, online documentation, photo and film collections, enriched authors’ biographies, searchable publications.

ជាអ្វីគ្រប់យ៉ាងដែលអ្នកទាំងអស់គ្នាចង់ដឹងអំពីអង្គរ, អរិយធម៌ខ្មែរពីបុរាណ, និងមូលហេតុអ្វីដែលធ្វើឲ្យមានការទាក់ទាញចាប់អារម្មណ៍ពីទូទាំងពិភពលោកបូករួមទាំងប្រទេសកម្ពុជានាសម័យឥឡូវនេះផងដែរ។

Our resources include the on-site Library at Templation Angkor Resort, Siem Reap, Cambodia, with exclusive access for the resort’s guests. Non-staying visitors can ask for a daily pass email hidden; JavaScript is required.