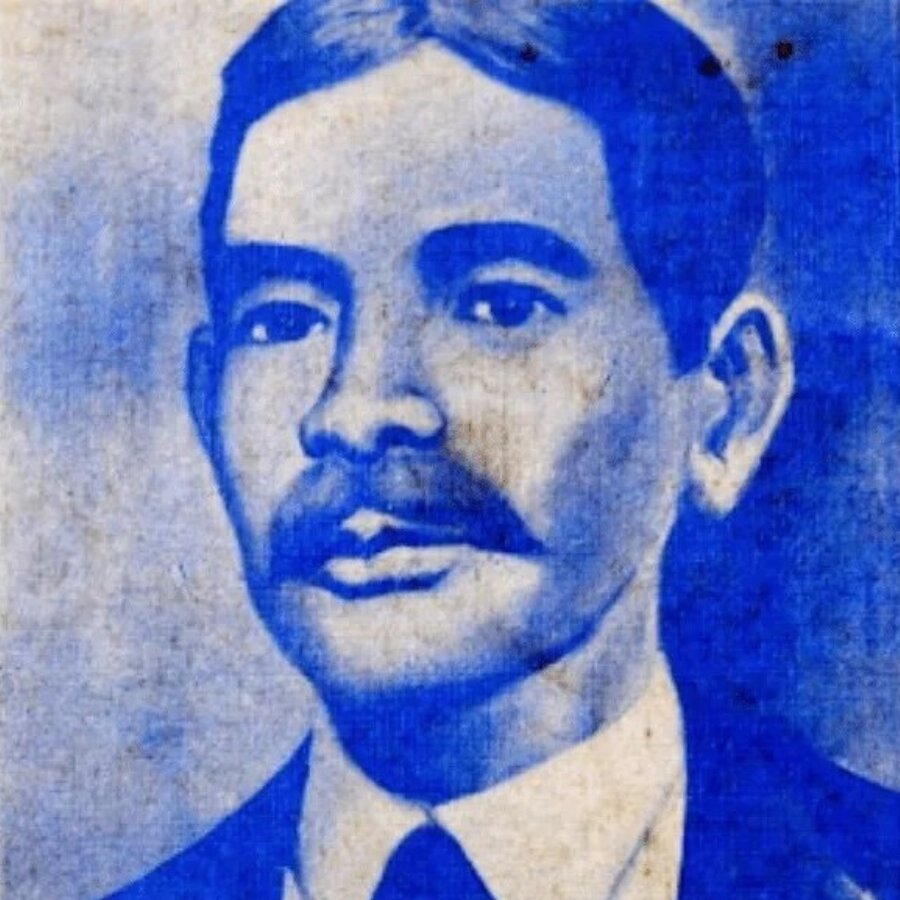

Oknha Suttantaprījā [Sothnpreychea] Ind សុត្តន្តប្រីជាឥន្ទ (22 July 1859, Rokar Korng Village, Kandal Province – 8 Nov. 1924, Battambang) was a Cambodian monk and writer whose work is considered as “pivotal” in the Cambodian literature transitional period between tradition and modernity.

His stanza poem Niras Nokor Wat - on which he worked between 1909 and 1915, his manuscript having been discovered posthumously and published by the Buddhist Institute in 1934 -, related to his attending of King Sisowath’s ceremony at Angkor on Thursday 23 September 1909, marking the 1907 retrocession of Siem Reap and Battambang provinces from Siam and possibly commissioned by the King, is a Khmer literary modern-classic work [1], an account of a “river journey [on the Sangke River] that becomes a meditation on life, desire, and impermanence,” according to Trent Walker. As Penny Edwards remarked, “Ind’s verse is burnished by his monastic training, Pali repertoire, and cosmopolitan schooling.” [“Inarguably Angkor”, in The Angkorian World, 2023, p 641.]

When Suttantaprija Ind was 15, he lived at Wat Prek Por, studying Pali scripts. At 18, he went to Phnom Penh to study under a Buddhist preacher called Prak at Wat Unalom. One year later, he studied with Lok Achar Sok for a year at Wat Keo pagoda, Battambang. He became a monk again when he was 20 at Wat Keo for one year, and went to study in Bangkok, Siam, in 1880. After seven years there he came back to Cambodia in 1887, during the time of Lok Prash Yakatha Chhum Khnon [th เจ้าพระยาอภัยภูเบศร (ชุ่ม อภัยวงศ์), kh ចៅពញាអភ័យភូបេស្ស (កថាថនឈុំ) Chao Ponhea Apheayphubet Kathatan Chhum [2]] (29 July 1861 – 27 Aug 1922), the last ruler of Battambang under Siamese control who appointed him Khon Vichit Voha and Hluong Vichit Vohar, special counselor, after he left the monastic life.

His life reflects the tensions between Cambodia, Siam and France at the time. For instance, his closeness to ‘viceroy’ Chhum could explain his choice of leaving for Bangkok, but also reflects the close family ties across the two countries: Chhum’s sister, acclaimed court dancer Khun Chom Iem Boseba [3](1864 – 1944), was one of King Norodom’s wives and, by giving birth to Prince Sutharot (1872−1945), at the origin of the Royal House of Norodom. But Chhum’s granddaughter, Princess Chao Sovathana ព្រះនាងចៅសុវឌ្ឍនា (th พระนางเจ้าสุวัทนา พระวรราชเทวี HRH Princess Suwattana) (15 Apr 1906- 10 Oct 1985) was to marry in 1924 Siam’s King Vajiravuth (Rama VI) April 15, 1906 — October 10, 1985), thus being Queen of Siam for less than one year. During his spare time, Ind was also fond to translate the famous French folktales by La Fontaine in Khmer [4].

According to researcher Thun Theara, he “had translated a chronicle manuscript from Siamese into Khmer. The manuscript was a Cambodian palace chronicle, probably translated from Khmer into Siamese during Ang Duang’s reign, and collected by the Siamese intellectual K. S. R. Kulap (see Khing 2012, 15). Ind had probably come across the manuscript during his years as a Buddhist monk studying in Bangkok in the 1880s. In 1917 there was an effort in Thailand to compile and publish Khmer chronicle manuscripts that had been translated into Siamese since the reign of King Mongkut in the 1850s. The Thai edition included three different versions of the original Khmer manuscripts: the Nubbarath version of 1878 on the pre – fourteenth-century period, a manuscript composed during Ang Duong’s reign in around 1855 on the 1346 – 1794 period, and another text acquired by Coedès in the 1910s on the 1794 – 1865 period. The edition was published as Ratchaphongsawadan Krung Kamphucha (Royal chronicles of Cambodia).” [in Epistemology of the Past: Texts, History, and Intellectuals of Cambodia, 1855 – 1970, New Southeast Asia: Politics, Meaning, and Memory, University of Hawaii Press, 2024, Kindle Edition, p 47) [5].

After staying at Wat Kandal (Battambang) for ten years, Suttantaprija Ind — then 37 — decided to leave the monkood and married Lok Yay Tuet from Chomka Somroung village, Battambang, living in Chivea Thom village. In ជីវប្រវត្តិអ្នកនិពន្ធខ្មែរ [Biography of Khmer Writers] by Chhay Sokhai ឆាយ សុខៃ and Meas Sopanha មាស សុបញ្ញា (Phnom Penh, 2016, p 134 – 5), we find that “in Battambang province everyone appreciated him for his contributions to society, called him Lok Achar Ind, and loved his work. People borrowed and hand-copied his works before they were published. The hand-copied books were passed around from person to person for reading and studying. Some people knew the entire collection of his poetry by heart. […] According to his daughter, Lone Ind, Suttantaprija Ind was frequently invited to talk about dharma and tell stories when there was an event or ceremony such as a wedding, open house, etc. He would come back home with a lot of money, which he would like to give away to his grandchildren. At night, he would lay flat on his stomach writing all night long.”

In 1914, at 55, Suttantaprija Ind was back to Phnom Penh with honors, being granted the title of Oknha by King Sisowath for his contribution to the knowledge of Cambodian religion and traditions. He was called back to contribute to new Pali School (Ecole de Pali), with temporary quarters in the Silver Pagoda, transferred in 1922 to the building where the Buddhist Institute was to be set [6]. He was particularly occupied with the preparation of a Pali-Khmer Dictionary, and with the Dharma’s saying verification department. He resigned his civil servant post at 65, returning to Battambang where he passed away a few months later, surrounded by his family.

___________

[1] According to Sharon May in her 2015 essay on Cambodian literature,“the Buddhist Institute, which printed Ukñā Suttantaprījā Ind’s famous Gatilok and other literature, became the nation’s first publisher in the early 1900s. Khmer-language newspapers and journals first appeared in the 1920s, although the first Khmer-owned and operated newspaper, Naggaravatta [Angkor Wat] did not appear until 1937. The first Khmer modern novel also appeared in the 1930s. A new Khmer term was invented for the novel, ប្រលោមលោក pralomlok, which means a story that is written to seduce the hearts of human beings. Many of these early works featured ill-fated lovers and contained moral and social critique. As was common for the era in Southeast Asia, and for writers such as Dickens and Tolstoy earlier in Europe, most novels were first serialized in newspapers or journals. Among the early novels still read today are The Waters of Tonle Sap by Kim Hak, The Tale of Sophat by Rim Kim, The Rose of Pailin by Nhok Them, and Wilted Flower by Nou Hach. Literature became linked with national identity, as quoted in the journal Kambuja Surya, “If its writing disappears, the nation vanishes.”

[2] Abhayavongsa อภัยวงศ์ was a Thai noble surname used by the Thai family that formerly governed parts of Cambodia at the time it was ruled by Siam. Despite its long presence in Cambodia, it was never considered part of the Khmer nobility. The Abhayavongsa family governed Phra Tabong Province (modern Battambang Province, Cambodia) for six generations from the late 18th century, when Siam annexed the Khmer territories, until 1907, when the area was ceded to French Indochina effectively reuniting it with Cambodia. The title bestowed by the Thai King to the governor of Phra Tabong which was used by each successive governor was Aphaiphubet [Apheayphubet]. [source: Wikipedia].

[3] บุษบาท่ Bus’ba in Thai means flower. In “The Gru of Parnassus: Au Chhieng among the Titans” (Udaya 15, 2021, p 127 – 82 [tr. by Robert Fowler], Grégory Mikaelian noted that

her filiation varies according to the family trees available: for Népote and Sisowath, Khun Cham Iem Bossaba is the daughter of a Battambang mandarin and a relative of the royal family of Thailand, without further specification (Népote and Sisowath, État présent, 68); for Corfield, Yem Bossaba is the sister of Thao Sri Sudorn-nath, herself the grandmother of Phra Nang Chao Suvadhana (1905−1985), who married Rama VI (also known as Vajiravudh) in 1924, (Corfield, The Royal Family, 47 – 48); for Nhiek Tioulong, Khun Chom Iem is the daughter of a titled dignitary, “Piphéak Bodin”, former governor of Siem Reap under Siamese authority, another of whose daughters, Mâm Keo, is the grandmother of Pranang Tiv, wife of Rama VI (Nhiek, Chroniques khmères, 44). At this stage, the divergences are easily resolved: the “Battambang mandarin” father of the two sisters (one of whom is the grandmother of one of the wives of King Rama IV) is none other than “Piphéak Bodin,” governor of Siem Reap falling within the orbit of the regents of Battambang (Loch, “Chronique des vice-rois de Battambang”). On the other hand, things become complicated when you try to clarify the identity of this dignitary and that of the mother of Iem. If you follow the genealogies of the Siamese royal family (“Khmer-Siam Royal Family Tree”), she is none other than the daughter of the eighth governor of Battambang (see likewise Khuon, Battambang et sa région, 119 and So, The Khmer Kings, Book II, 372).

[4] In his monograph on Suttantaprija Ind, Khing Hoc Dy noted that he helped Père [Father] S. Tandart in his research on Khmer language when the Catholic missionary was active in Battambang. The latter published a few years later S. Tandart, Dictionnaire Français-Cambodgien, t 1, Hong-Kong, Imprimerie de la Société des Missions-Etrangères, 1910, 1104 p. In his review of the dictionary (Toun’g Pao, vol 13, 1912, p 744 – 5), Henri Cordier noted that the same author was “set to publish an Essay on Khmer Grammar.” We do not know whether this project came to fruition.

[5] Known as “Royal Chronicle ME”, since the manuscript is kept at the library of the Missions-Étrangères (ME) in Paris. In his Histoire du Cambodge… (p 15), historian Mak Phoeun noted that this chronicle was “apparently a translation into Khmer — made around 1909 (?) under the reign of Sïsuvatthi (Sisowath) (1904−1927) by the Achary “Ind”, later known as Ukañā Suttant Prījā “Ind” (1859 — 1924) — of a Cambodian royal chronicle previously translated into Siamese. It starts with King Rām de Joen Brai (or Rām I) and ends in 1811 AD. The text often records the same facts than other royal chronicles, yet is much more detailed in relation to events reported from the end of the 18th century, with a slightly different list of kings for the end of 17 th century.”

[6] It has often be said that Ind had worked at the Buddhist Institute but this institution was founded on 12 May 1930 by King Sisowath Monivong of Cambodia, King Sisavong Vong of Laos, the Governor General of Indochina Pierre Pasquier and George Coedès, then director of the EFEO.

Publications

- ព្រះរាជពង្សាវតារខ្មែរ [Preah Reach Pongsavatta Khmae] [Khmer Royal Chronicle], tr. from Thai by I.S [5].; tr. FR, Martine Piat, “Chroniques royales khmer”, BSEI, XLIX, n 1, p 35 – 44, n 2, 1974, p 859 – 74.

- និរាសនគរវត្ត Niras Nokor Wat [A Journey To Angkor Wat; “Séparation of Angkor” following Khing Hoc Dy’s French translation], 1st edition 1924, Buddhist Institute, Phnom Penh, repub. 1969, 1998.

- ចំបាំងតាកែ ភ្នំក្រវ៉ាញ [Chambang Ta kè Phom Kravanh], tale.

- រឿងអំបែងបែក Rueng Ambeng Bek [Broken Pot Story], novel in verse, Phnom Penh, 1953.

- បឋមសម្ពោធិ Pakthorm Somphoti, poem.

- លោកនីតិបករណ៍ Lok Nitepkor, poem.

- សុភាសិតច្បាប់ស្រី Sopheasit Chbap Srey [Useful Bits of Advice for Women], Buddhist Institute, Phnom Penh, (2502), 1959; tr. FR: La morale aux jeunes filles, coll. Culture et civilisation khmeres, n 9, Phnom Penh, Buddhist Institute, 1965.

- គតិលោក Katilok [or Gatilok] [Walk in The World], 10 episodes published by the Buddhist Institute, Phnom Penh, 1971. [digital version via ៥០០០ឆ្នាំ 5,000 years website]

- ក្បួនមេកាព្យ Kboun Maykab [Rules for a Leader], Buddhist Institute, Phnom Penh, undated.

- សុត្តន្តប្រីជាឥន្ទនិងស្នាដៃ [Suttantaprija Ind and his Works], Khing Hoc Dy ed., Phnom Penh, Angkor Press, 2012.

See also

- Chhay Sokhai ឆាយ សុខៃ & Meas Sopanha មាស សុបញ្ញា, ជីវប្រវត្តិអ្នកនិពន្ធខ្មែរ [Biography of Khmer Writers], Phnom Penh, 2016, p 134 – 5.

- សៀវភៅឧកញ៉ាសុត្តន្តប្រីជាឥន្ទនិងសេចក្ដីសង្ខេបអំពីស្នាដៃមួយចំនួនរបស់លោក [The Book of Suttantaprija Ind and a summary of some of his works], research document by Seng Sovannada សេង សុវណ្ណដារ៉ា, Cambodian Writers’ Association សមាគមអ្នកអក្សរសិល្ប៍កម្ពុជា, Phnom Penh, BE 2565 (2022).