Danses Cambodgiennes (Cambodian Dance)

by Oknha Veang Thiounn & Sappho Marchal

The first complete study on Khmer classical (royal) dance by a Cambodian researcher, Minister of the Royal Palace in the 1920s.

- Formats

- e-book, ADB Physical Library, hardback

- Publisher

- Institut Bouddhique, Imprimerie Cambodia, Phnom Penh, 1927

- Edition

- 3d edition from the 1927 and 1956 publications, revised by Jeanne Cuisinier. Foreword by M.P. Pasquier. (#39 at Angkor Database Library)

- Published

- 1968

- Authors

- Oknha Veang Thiounn & Sappho Marchal

- Pages

- 202

- Language

- French

With his profound knowledge of the Reamker (Khmer version of the Ramayana epic), and his access to the Royal Palace where the dancers of the Royal Ballet were still strictly confined, Samdech (Lord) Chaufea Veang Thiounn was well-equipped to attempt a comprehensive and vivid study of Cambodian classical dance techniques and choreography.

Contemporary with George Groslier’s important essays on the same subject, this book is beautifully illustrated by Sappho Marchal, the daughter of Angkor Curator Henri Marchal who, at the same period, was carefully studying the garments and ornaments of Angkor Wat sculpted apsaras.

Detailing the color code of masks and costumes in Khmer classical dance, the author offers a condensed yet luminous analysis of gestures, individual and group motions, symbolical expressiveness of choreographic tableaux. With precise examples, the author shows how the Khmer female dancers and ballet masters have adapted (some would say ‘perfected’) to their own style the 28 mudras (hand gestures) compiled in the old Indian treatise Abhinaya Darpana.

Also described in this essential work are the formative years of the Royal dancers, their practice sessions and their mastery of an ancient art in which “every single gesture has the meaningul power of an articulated word”. And the musical phrases developed with the choreography are detailed with the same elegant accuracy.

Tags: Royal Ballet of Cambodia, dance, dancers, Reamker, mudras

About the Authors

Oknha Veang Thiounn

Samdech Chauvea (‘Lord Prime Minister’, in Khmer) Thiounn (8 Apr. 1864, Kompong Chhnang — Sep. 1946, Phnom Penh), also called Samdech Chauvea Veanjay (“Lord Head of the Palace”) served as Prime Minister, Minister of The Royal Palace and Treasury, and Minister of Fine Arts under the French Protectorate. He started his public career as an interpreter and advisor for several French explorers, in particular as an attaché to the Mission Pavie. He also served as Prime Minister under King Norodom Sihanouk in 1941.

In 1885, Auguste Pavie recommended him to the École Cambodgienne in Paris, where 13 Cambodian young men were trained as interpreters (the school was located in Hotel de Saxe, rue Jacob). Three years later, Thiounn served as interpreter for the Pavie Mission.

1) A portrait of Samdech Thiounn, date unknown. 2) Minister Thiounn (far left), King Sisowath and two French officials at the ‘Revue de Longchamp’ during the 1906 royal visit to France [photo published in L’Illustration, March 1906].

In 1906, Thiounn [a French transliteration of Chuon] assisted King Sisowath of Cambodia during the King’s official visit to France, witnessing the performances (the first ones ever outside of the Royal Palace) of the Cambodian Royal Ballet. His account of the journey during which he developed his interest in Khmer classical dance (Voyage du roi Sisowath en France, translated from Khmer into French by Olivier de Bernon in 2006) remains a reference (1). He was closely vinculated to the Royal Ballet, as he married Malis Le Faucheur, daughter of Paul Le Faucheur and Royal Ballet dancer Anak Sok.

After publishing a documented study on the frescoes at the Royal Pagoda Preah Oubosoth Rottanaram in 1903, with important insights on the Reamker mythology and symbolic, Samdech Chaufea (or Chauffa, another French version of the Khmer title ចៅហ្វា chauvea) Thiounn wrote an essay on Khmer classical choreography, Danses Cambodgiennes (published by the Phnom Penh Buddhist Institute and illustrated by artist-researcher Sappho Marchal). He also took an important part in the foundation of the Musee Albert Sarraut (later National Museum of Cambodia) and the Ecole des arts cambodgiens (later Royal University of Fine Arts), and actively collaborating with Suzanne Karpelès in editing the Kambuja Surya review.

Blamed by Prince Yukhantor for being too lenient to French authorities, he resisted political turmoil, only to be sacked at the request of Vichyist French admiral Jean Decoux, replaced by Ung Hy. He was the only minister who served under the consecutive reigns of King Norodom, King Sisowath and King Monivong.

(1) Samdech Chaufea Thiounn’s account of King Sisowath’s 1906 journey has been published in Khmer in 2006, edited by Olivier de Bernon and Michel Antelme : ព្រះករុណាព្រះបាទសម្តេច ព្រះស៊ីសុវត្ថិ ព្រះចៅក្រុងកម្ពុជាធិបតី ព្រះរាជដំណីរេទៅក្រុងបារាំងសស ឆ្នាំមមីអដ្ឋស័ក៏ត្រូវនឹងឆ្នាំបារាំង (Voyage du roi Sisowath en France, en l’année du Cheval, huitième de la décade, troisième du règne, correspondant à l’année occidentale 1906, par l’Oknha Veang Thiounn), [King Sisowath’s journey to France, in the year of the Horse, eighth of the decade, third of the reign, corresponding to the Western year 1906, by Oknha Veang Thiounn], Phnom Penh, Éditions de la Bibliothèque Nationale [National Library Press], 2006, 189 p; revised repr. National Bank of Cambodia Press, 2023, 228 p.].

Sappho Marchal

Author and artist Sappho Marchal-Brébion (1904, Paris — 2000), the daughter of French archeologist and Angkor Wat Conservator Henri Marchal, was the first researcher to study, document in drawings and count the numerous female stone figures in Angkor Wat.

Sappho (sometimes spelled Sapho) Marchal came to Cambodia as a toddler, in 1905. She grew up in Siem Reap and on the archeological sites her father — appointed Angkor Conservator in 1916- supevervised. As a young artist, she illustrated many scientific articles published by Henri Marchal.

While capturing with her pen the slightest details of costumes and ornaments worn by devatas and apsaras around the Khmer temple complex, Sappho Marchal inventoried 1,737 female sculptures and carvings in Angkor, not far from the account of 1,796 established by Kent Davis seventy years later (probably because the young artist did not have access to the upper levels of the Angkorian towers).

At only 23 years of age, Sappho Marchal published a sum of her drawings and observations in Costumes et Parures khmèrs d’après les Devatâ d’Angkor-Vat (Paris, 1926, re-published in 1931). She also authored a collection of illustrations on Khmer traditional choreography for Samdech Thiounn’s book, Danses cambodgiennes (Editions d’Extreme Asie, Saigon, 1927). Both books, along with George Groslier’s own work, inspired Queen Kossamak of Cambodia when the Queen gave a new stimulus to the Royal Ballet traditions with the “Apsara Dance”.

Sappho Marchal with her parents, Henri and Mary, 1) circa 1907, 2) in 1920 [source: EFEO, in Henri Marchal: un architecte à Angkor, EFEO/Magellan, 2020]

On April 7, 1927, Sappho Marchal gave a lecture for the Revue des Arts Asiatiques members in Paris, La Danse au Cambodge, with a ‘démonstation choréographique’ by Nyota lnyoka [the Japanese founder of a ‘exotic dance school’ attended by Suzanne Meyer, daughter of Royal Ballet dancer Saramani and author Roland Meyer under the artist name Saramani] and film screenings. The Revue was to report (vol 4−2,1927, p 130) : “Devant la salle pleine, d’une voix tranquille, douce, et dont pas une syllabe n’était perdue, Mlle Marchal essaya de communiquer a son auditoire l’admiration et l’affection qu’elle éprouve pour Ies petites danseuses cambodgiennes et l’enthousiasme que lui inspire leurs danses. Nous regrettons d’être dans l’impossibilité de donner aujourd’hui le texte de cette conférence nourrie d’une très riche documentation, mais Mlle Marchal est repartie pour Angkor, et elle a emporte son manuscrit.” [In front of a full hall, in a quiet, gentle voice, not a syllable of which was lost, Miss Marchal tried to communicate to her audience the admiration and affection she feels for the little Cambodian dancers and the enthousiasm inspired by their dances. We regret not being able to give here the text of this conference, nurtured by a very rich documentation, but Miss Marchal has gone back to Angkor, and she has taken her manuscript with her.]

We know that she moved to France in 1928, and that her parents stayed with her there during the Second World War, from 1938. She was then known as S. Brébion-Marchal, possibly after marrying the son of journalist-researcher Antoine Brébion (1857−1917), author of a “Bibliographie des voyages dans l’Indochine francaise du IX au XIX eme siecle”. In the 1960s, Sappho came back to Cambodia in two occasions to pay visits to his father Henri Marchal, who had retired in his Khmer traditional house with his Cambodian companion, Neang Niv, near Wat Phu, Siem Reap.

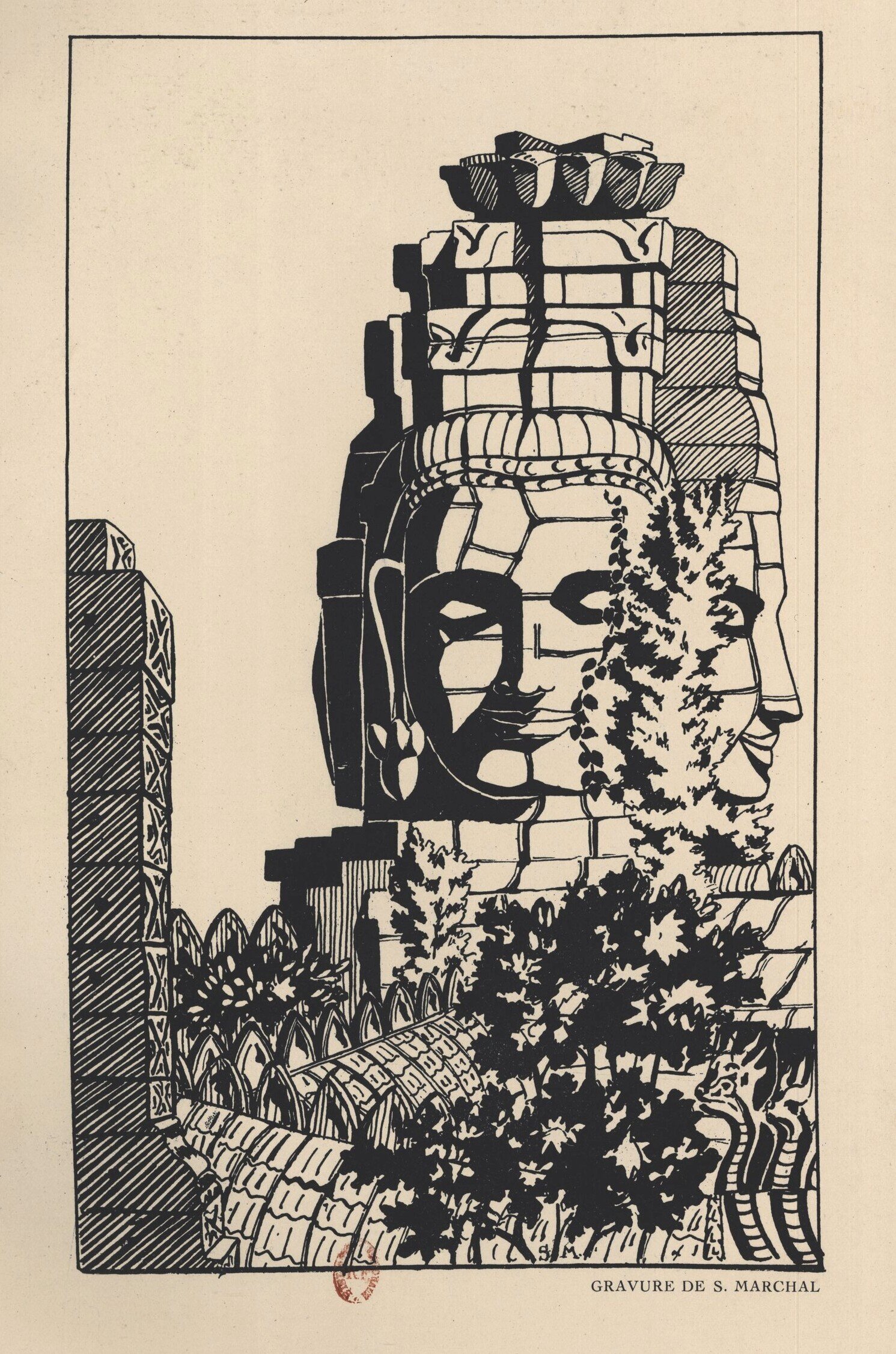

1) Drawing in Angkor in the 1920s [source: devata.org]. 2) An etching by Sappho Marchal, 1924 [source: Les Pages Indochinoises, 15 April 1924, frontispiece].