L’Enseignement et la mise en pratique des Arts indigènes au Cambodge (1918-1930)

by George Groslier

[under construction]

- Format

- e-book

- Published

- 1931

- Author

- George Groslier

- Pages

- 41

- Language

- French

pdf 2.4 MB

About the Author

George Groslier

George Groslier [kh ហ្សក ហ្រ្គូសលីយេ, jp ヂョルヂュ・グロスリエ] (4 Feb. 1887, Phnom Penh — 16 June 1945, Phnom Penh), the first child with French citizenship born in modern Cambodia, was an artist, novelist, historian, archaeologist, ethnologist, architect, photographer, and the founder and curator of the National Museum of Cambodia in 1917, as well as the Ecole des arts cambodgiens (School of Cambodian Arts).

While organizing the School of Cambodian Arts (nowadays the Royal University of Fine Arts), Groslier has extensively portrayed and studied the country, its people and its traditions, in his writings, paintings and erudite communications. He founded Phnom Penh Albert Sarraut Museum in 1919, later to become the Cambodia National Museum [Groslier’s wife, Suzanne Poujade (1893−1970), was a niece of Albert Sarraut, former Governor-General of Indochina and then French Minister of the Colonies and future Prime Minister]. The interconnection between the Museum and the School did not survive his death, as the Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient took over the Museum in 1945 [see Gabrielle Abbé, Le développement des arts au Cambodge a l’époque coloniale: George Groslier et l’Ecole des arts cambodgiens (1917−1945”, Udaya 12, 2014: 7 – 39]

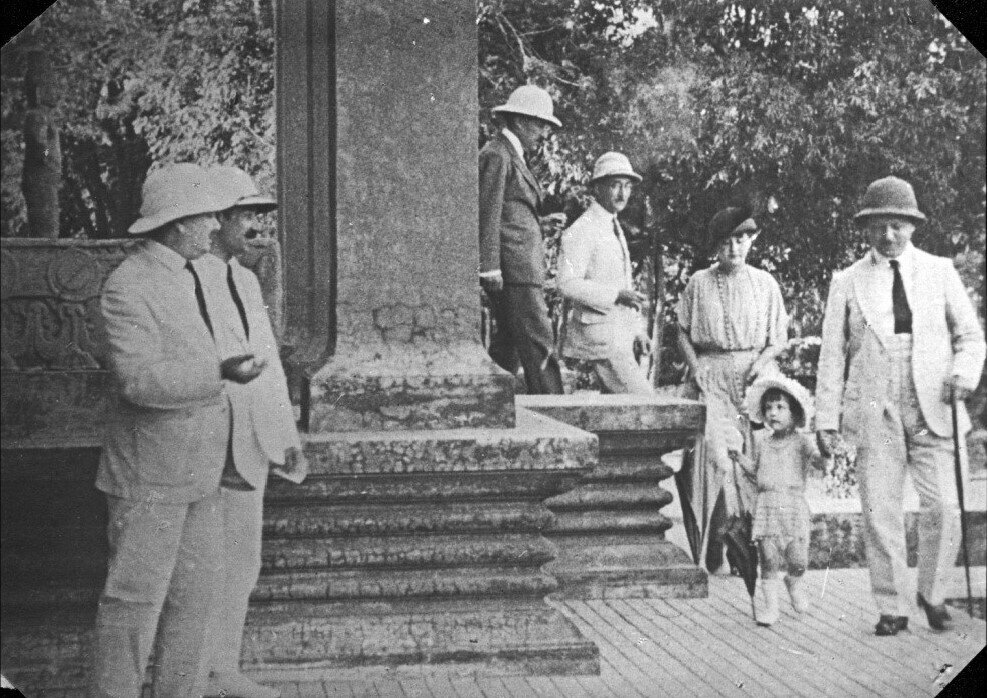

1) Suzanne Poujade and two of the Grosliers’ three children in the 1920s (EFEO). 2) George Groslier with daughter Nicole and Suzanne Poujade, far right, arrive at the Phnom Penh Museum for the 1922 visit of Maréchal Lyautey. Standing on the left side, André Silice and Jean Stoeckel, Groslier’s collaborators [photo courtesy of Kent Davis].

1) Suzanne Poujade and two of the Grosliers’ three children in the 1920s (EFEO). 2) George Groslier with daughter Nicole and Suzanne Poujade, far right, arrive at the Phnom Penh Museum for the 1922 visit of Maréchal Lyautey. Standing on the left side, André Silice and Jean Stoeckel, Groslier’s collaborators [photo courtesy of Kent Davis].

1) Suzanne Poujade and two of the Grosliers’ three children in the 1920s (EFEO). 2) George Groslier with daughter Nicole and Suzanne Poujade, far right, arrive at the Phnom Penh Museum for the 1922 visit of Maréchal Lyautey. Standing on the left side, André Silice and Jean Stoeckel, Groslier’s collaborators [photo courtesy of Kent Davis].

George Groslier was detained and tortured by the Japanese forces when Japan, a former ally of Petain’s French government, occupied vast swaths of South East Asia. Le Journal de Saïgon (7 Dec. 1945) reported six months after his death: “Le 9 mars 1945, Georges Groslier était hospitalisé ; rétabli, il habite le camp où il rédige pour lui un journal de l’occupation japonaise. Le 1er juin, une rechute l’oblige à rentrer à nouveau à l’hôpital. Le 16 juin, il est arrêté par les Japonais, sorti de son lit et conduit à la Gendarmerie japonaise. Interrogé, torturé, il meurt à la suite du supplice de l’eau. Incinéré, ses cendres sont remises le 22 juin à sa famille. Déposé à la chapelle de l’Évêché, l’urne funéraire en sort le 25 juin pour être transportée au cimetière. Les dirigeants du camp français obtiennent des autorités japonaises que l’urne traverse le camp français et que 20 Français soient autorisés à sortir du camp pour l’accompagner au cimetière. Le matin du 25 juin, à 8 heures, le petit cortège traverse le camp, tous les Français sont rangés sur son parcours : dernier hommage à une noble victime.” [“On March 9, 1945, Georges Groslier was hospitalized; after he recovered, he lived in the camp where he wrote a diary of the Japanese occupation. On June 1, a relapse forced him to return to the hospital. On June 16, he was arrested by the Japanese, taken from his bed, and taken to the Japanese military police. Interrogated and tortured, he died following the water torture. Cremated, his ashes were given to his family on June 22. Placed in the chapel of the Bishopric, the funeral urn left on June 25 to be transported to the cemetery. The leaders of the French camp obtained from the Japanese authorities that the urn cross the French camp and that 20 French people be authorized to leave the camp to accompany it to the cemetery. On the morning of June 25, at 8 a.m., the small procession crossed the camp, all the French people lined up along its route: a final tribute to a noble victim.” Later, George Groslier’s ashes were transferred to France by his family, and have been interred in the family crypt in the 2020s.

With Suzanne Poujade, he had three children, Nicole, Gilbert and Bernard-Philippe, the latter following his father’s steps and becoming an eminent researcher in Cambodian archaeology and history.

George Groslier’ scientific and artistic contribution to Khmer archaeology and cultural history is celebrated, as well as his committment to protect the Cambodian cultural heritage — for instance when he successfully prevented André Malraux to take abroad the spoils of his plundering of Banteay Srei temple. Researcher Kent Davis has described him as ‘Le Khmerophile’ par excellence in the most complete biographical work about him, and has edited the English translation of five of Groslier’s major contributions (all published by DatASIA Press). Recent works by young researchers, however, have claimed that his official responsibilities somehow submitted him to the French colonial system, and his often pessimistic outlook of the “decline of the Cambodian arts” played along with the colonial system.

Nevertheless, his important photographic work on the rehearsals of the Royal Ballet dancers in 1927 has been restored and presented to the public in 2019. His statue still remains pre-eminent at the National Museum, and the debate around the validity of giving back the name of Rue Groslier (Groslier Street) to the lane accessing the Museum was still ongoing in the 2020s [see here].

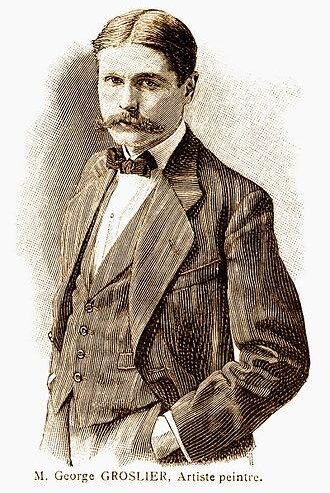

1) George Groslier portrayed in 1913 in the French journal Femina. 2) George Groslier hodling a Khmer Prajnaparamita statue at his desk in 1926, by Martin Hürlimann (© National Museum of Cambodia).

1) George Groslier portrayed in 1913 in the French journal Femina. 2) George Groslier hodling a Khmer Prajnaparamita statue at his desk in 1926, by Martin Hürlimann (© National Museum of Cambodia).

1) George Groslier portrayed in 1913 in the French journal Femina. 2) George Groslier hodling a Khmer Prajnaparamita statue at his desk in 1926, by Martin Hürlimann (© National Museum of Cambodia).

Publications

[based on “Works by George Groslier”, in Cambodian Dancers Ancient and Modern, Kent Davis (ed.), Holmes Beach (USA), DatASIA, 2011: 298 – 303.]

- La Chanson d’un jeune, self-published, 1904.

- Les Ruines d’Angkor. Indochine, 1911.

- Danseuses cambodgiennes anciennes et modernes. Paris: A. Challamel, 1913. | ENG: Cambodian Dancers Ancient and Modern, Kent Davis (ed.), Holmes Beach (USA), DatASIA, 2011, 461 p. ISBN 978−1−934431−03−3 [printed in Cambodia].

- A l’ombré d’Angkor; notes et impressions sur les temples inconnus de l’ancien Cambodge, avec 16 photographies inédites d’après les clichés de l’auteur et une carte itinéraire. Paris: A. Challamel, 1913. | ENG: In the Shadow of Angkor, Unknown Temples of Ancient Cambodia, ed. Kent Davis, foreword by Milton Osborne, DatASIA, 2014, 188 p. ISBN 978 – 1934431900. [and Kindle edition].

- Angkor, ouvrage orné de 103 gravures et de 5 cartes et plans. Paris: H. Laurens, 1924. | ENG: Angkor, with 103 illustrations, 5 maps and plans. Translated by Paule Fercoq Du Leslay. Evreux: impr. Hérissey, 1933. | JP: アンコオル遺蹟 (Ankoru iseki), tr. by Miyake Ichirō 三宅一郎, Tokyo, Shinkigensha 新紀元社., 1943.

- Recherches sur les Cambodgiens d’après les textes et les monuments depuis les premiers siècles de notre ère. Paris: A. Challamel, 1921.

- [editor] Arts et Archéologie Khmers. Revue des Recherches sur les Arts, les Monuments et l’Ethnographie du Cambodge, depuis les origines jusqu’à nos jours. Paris: Société d’ Editions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales, 1921 – 1926 [2 vols].

- Catalogue du Musée de Phnom Penh. Hanoï, IDEO, 1924.

- La sculpture khmère ancienne; illustrée de 175 reproductions hors texte en similigravure. Paris: G. Crès, 1925.

- [novel] La Route du plus fort. Paris, Emile-Paul frères, 1926. Reissued by Kailash, 1994 (ISBN 2−909052−52−4). | ENG: The Road of the Strong: A Romance of Colonial Cambodia (English and French Edition), ed. by Kent Davis, foreword by Henri Copin, DatASIA, 2017, 398 p, ISBN 978 – 1934431160.

- [novel] Le Retour à l’argile. Paris: Emile-Paul frères, 1928. Reissued by Kailash, 1994 (ISBN 2−909052−49−4). | ENG: Return to Clay, A Romance of Cambodia, ed. by Kent Davis, foreword by Henri Copin, DatASIA, 2014, 276 p. ISBN 978 – 1934431948.

- Les collections khmères du Musée Albert Sarraut à Phnom-Penh. Paris: G. van Oest, 1931.

- Eaux et lumières; journal de route sur le Mékong cambodgien. Paris: Société d’éditions géographiques, maritimes et coloniales, 1931. | ENG: Water and Light, Personal Glimpses of the Cambodian Mekong, ed. by Kent Davis, foreword by Henri Copin, DatASIA,2016, 342 p. ISBN 978 – 1934431870.

- L’Enseignement et la mise en pratique des Arts indigènes au Cambodge (1918−1930), Paris : Société d’éditions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales [offpr. Bulletin de l’Académie des Sciences Coloniales 26], 1931, 41 p., 4 pl.

- Angkor. Paris. Laurens, Les Villes d’Art célèbres, 1932.

- [novel] Monsieur de la Garde, roi. Roman, inspiré des chroniques royales du Cambodge. Paris: La Petite Bibliothèque de L’Illustration, 1934.

- [novel] Les Donneurs de Sang, Phnom Penh et Saigon. Saigon: Albert Portail, 1941.

Archeological Publications

- “Objets anciens trouvés au Cambodge”. Revue archéologique, 1916, 5e Série, vol. 4, pp. 129 – 139.

- “La batellerie cambodgienne du VIIIe au XIIIe siècles”. Revue archéologique, 1917, 5e Série, vol. 5, pp. 198 – 204.

- “Objets cultuels en bronze dans l’ancien Cambodge.” Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1921 – 3, vol. 1, fasc. 3, pp. 221 – 228.

- “Le temple de Phnom Chisor.” Ibid, vol. 1, fasc. 1, pp. 65 – 81.

- “Le temple de Ta Prohm (Ba Ti)”. Ibid, vol. 1.. fasc. 2, pp. 139 – 148.

- “Le temple de Preah Vihear”. Ibid, 1921 – 1922, vol. 1. fasc. 3, pp. 275 – 294.

- “Essai sur l’architecture classique khmère”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1923, vol. 1, fasc. 3. pp. 229 – 273.

- “L’art khmèr”. Paris, Arts et Décoration, août 1923. vol. 27. N” 260, pp. 34 – 40.

- “L’art du bronze au Cambodge”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1923. vol. 1, fasc., pp. 413 – 423.

- “L’Art khmer”. Paris, Arts et Décoration, August 1923, vol. 1, pp. 413 – 423.

- “Amarendrapura dans Amoghapura”. Bulletin de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (BEFEO) 24, 1924: 359 – 372.

- “La céramique dans l’ancien Cambodge”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1924, vol. 2, fasc. 1, pp. 31 – 64.

- “La vie à Angkor au XIe siècle”. Saigon, Pages Indochinoises, 15 – 1‑1924, N.S., vol. 1, pp. 9 – 17.

- “Les empreintes du ‘Pied du Buddha’ d’Angkor Vat”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1924, vol. 2, fasc. 2. pp. 65 – 80.

- “La région d’Angkor”. Ibid., pp. 113 – 130.

- “La région du Nord-Est du Cambodge et son art”. Ibid., pp. 131 – 141.

- “L’Asram Maha Rosei”, Ibid., pp. 141 – 146.

- “L’Art hindou au Cambodge”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1924. vol. 2, fasc. 1, pp. 81 – 93.

- “Essai sur le Buddha khmèr”. Ibid., pp. 93 – 112.

- “Sur les origines de l’Art khmèr”. Mercure de France, 1‑xii-1924, vol. 176, N° 365, pp. 382 – 404,

- “Les influences grecques au Cambodge et l’art pré khmèr”. Paris, L’Art Vivant, 1925.

- “Sur la route d’Angkor: le Prasat Phum Prasat”. Saigon, Extrême-Asie, déc. 1925, N” 14, vol. 12, pp. 493 – 494.

- “Introduction à l’étude des arts khmèrs”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1925, vol. 2. fasc. 2, pp. 167 – 234.

- “La femme dans la sculpture khmère ancienne”. Paris, Revue des Arts asiatiques, 1925, vol. 2, fasc. 1, pp. 35 – 41.

- “La fin d’Angkor”. Saigon, Extrême-Asie, Sept. 1925.

- ” Note sur la sculpture khmère ancienne”. Hanoi, Études asiatiques, École Française d’Extrême-Orient, 1925. vol. I, pp. 297 – 314.

- “A propos d’art hindou et d’art khmèr”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1926, vol. 2, fasc. 3, pp. 329 – 348.

- “Les collections khmères du Musée Albert Sarraut”. Ars Asiatica, XVI, Paris, G. Van Oest, 1931.

- Les Villes d’Art célèbres

- “Les Temples inconnus du Cambodge”. Paris, Toute la terre, June 1931.

- “Troisième recherché sur les Cambodgiens”. BEFEO 35, 1935: 159 – 206.

- “Une merveilleuse cité khmère. Banteai Chhma, ville ancienne du Cambodge”. Paris, L’Illustration, 3 April, 1937, N° 4909, pp. 352 – 357.

- “Les Monuments khmers sont-ils des tombeaux?” Saigon. Bulletin de la Société des Eudes Indochinoises, n.s. 16 – 1, 1941: 121 – 126.

Publications on Cambodian Arts and Culture

- “La convalescence des Arts cambodgiens”. Hanoi, Revue Indochinoise, Imprimerie d’Extrême-Orient, 2e sem. 1918, p. 207; 1er sem. 1919, pp. 871 – 890, 22 p. ill. p. 16, fig. 21.

- “La tradition cambodgienne”, Revue Indochinoise 1918: 459 – 469.

- “L’agonie de l’art cambodgien”, Revue indochinoise XXIX‑6, June 1918.

- “Question d’art indigène”. Hué, Bulletin des Amis du Vieux-Hué, Oct.-Dec. déc. 1920, pp. 444 – 452.

- “Étude sur la psychologie de l’artisan cambodgien”. Arts et Archéologie khmers, 1921, vol. 1, fasc. 2, pp. 125 – 137.

- “Seconde étude sur la psychologie de l’artisan cambodgien”. Ibid., pp. 205 – 220.

- “Royal Dancers of Cambodia”. Asia, 1922, vol. 22, N° 1, pp. 47 – 55, 74 – 75.

- “Soixante-seize dessins cambodgiens tracés par l’oknha Tep Nimit Mak et l’oknha Reachna Prasor Mao”, Arts et Archéologie khmers. Paris: Société d’Edition Géographique, Maritime et Coloniale, 1923: 331 – 386.

- “The Oldest Living Monarch”. Asia, 1923. vol. 23. pp. 587 – 589.

- “La reprise des arts khmèrs”. La Revue de Paris, 15 Nov. 1925: 395 – 422.

- “Propos sur la maison coloniale”. Saigon, Extrême-Asie, 3º trim. 1926, pp. 2 – 10; March 1927, pp. 307 – 366.

- “Les premieres funerailles du Roi Sisowath”. L’Illustration, 8 Oct. 1927, n° 4414: 388 – 91.

- “Avec les danseuses royales du Cambodge”. Mercure de France, 1 May 1928, pp. 536 – 565.

- “Les cérémonies d’incinérations de S.M. Sisowath”. L’Illustration, 28 Apr. 1928, n°4443: 410 – 15.

- “Le Singe qui montre la Lanterne magique”. Saigon, Extrême-Asie, Feb. 1928, pp. 347 – 366; mars 1928, pp. 435 – 450; avril 1928, pp. 499 – 505; mai 1928, pp. 546 – 554.

- “Die Kunst der Kambodschanischen tänzerinn”. Munich, Atlantis, Jan.-Mar. 1929, vol. 1,pp. 10 – 16; “Die Tanzerinnen des Konigs”, Ibid., p 16. 2 plates (1 col.).

- “Le théâtre et la danse au Cambodge”. Paris, Journal Asiatique, Jan.-Mar. 1929. vol. 214, pp. 125 – 143.

- “Contemporary Cambodian art studied in the Light of the Past Forms”. Boston, Eastern Art, 1930. vol. 2, pp. 127 – 141.

- “La Direction des Arts cambodgiens et l’École des Arts cambodgiens”. Saigon, Extrême-Asie, March 1930, N° 45, pp. 119 – 127.

- “La fin d’un art”. Paris, Revue des Arts Asiatiques, 1929 – 1930, vol. 6, fasc. 3., pp. 176 – 186; p. 184 et 251, fasc. 4, pp. 244 – 254.

- “La fin d’une tradition d’art: les pagodes cambodgiennes et le ciment armé”. L’Illustration, January 11, 1930, vol. 175, pp. 50 – 53.

- “De Pagode en Pagode”. Paris. Toute la Terre, July 1931.

- “L’Orfevrerie cambodgienne à l’Exposition Coloniale”. Paris, La Perle, 1931.

- “Rapport sur les arts indigènes au Cambodge”. Congrès International et Intercoloni de la Société Indigène, Paris. 1931.

- “Les Arts indigènes au Cambodge”. Exposition internationale des Arts et Techniques, Indochine Française, Paris, 1937.

- “Les Arts indigènes au Cambodge”. 10th Congress of the Far-Eastern Association of Tropical Medicine, Hanoi, 1938, pp. 161 – 181.

Misc.

- “C’est une idylle…”. Paris, Mercure de France, July 1929.

- La Mode masculine aux colonies. Paris: Adam, 1931.

- “Nos boys”. Saigon, Extrême-Asie, August 1931, N° 55, pp. 69 – 76.