klon

th กลอน | la ກອນ

Klon [or glawn, gaun] is a Thai and Lao term referring to 1) poetic verse in general, 2) a specific prosodic form in Thai and Lao poetic traditions.

by Rajanubhab Damrong

A quite ambivalent account of the 1924 visit to Phnom Penh and Angkor by a Siamese dignitary: shared cultural heritage in a time of rising nationalism.

pdf 59.1 MB

Is this short, elegant and sometimes elusive book the travelogue of Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, a younger brother of King of Siam Chulalongkorn (1853−1910) [Rama V] and a noted expert in the archaeology of Southeast Asia visiting Cambodia in 1924, or is it what the Thai title [นิราศนครวัด] clearly states, a Nirat (นิราศ), a genre of Thai literature “designated as a distinct type of poetry composed during a journey, characterized by its expression of longing and sadness from being separated from loved ones, which can be either a real separation, a fictional one, or an imaginative one”? [as defined by Nutcha Suwanmalee in a 2022 contribution to Thailand Foundation’s website].

Exactly one century after the famed journey, and as the first English translation of the full text is released in December 2024, with the presentation at The Siam Society by editors Peter Skilling and Chris Baker, it seems useful to go back to the original version, and to replace this prose “poem of separation” of Angkor Wat in its historic context, particularly the relations between the Kingdom of Siam and its former “vassal state”, Cambodia then under the French protectorate.

After a short klon (poem) depicting the mood of Prince Damrong, the book opens with the traveling party boarding in November 1924 the boat of the Siam Steam Navigation Compagny Boat that will leave them in Kampot (a change from the typical route Bangkok-Singapore: the three “sweet daughters of the Prince, Princess Pilailekha Diskul (1907−1985), Princess Poonpisamai — the one who was to accompany his father in another, more controversial, trip to Cambodia, this time to Prasat Preah Vihear, in January 1930 — and Princess Patthanayu; French EFEO researcher George Coedès - then head of the Royal Library of Bangkok -, “Professor Coedes’ wife, who was taking their children to visit relatives in Phnom Penh [tactfulness or embarrassment, the Prince never writes Coedes’ wife’s full name, Neang Yap, a niece of Oknha Chakrey Pich Ponn], Luang Suriyapongphisutthaphaet, “serving as doctor and interpreter”, Phraya Pojanpreecha (“who had received special permission to leave by the Ministry of the Palace”), Mr. Somboon Chotichit, “clerk”, and several servants.

At landing in Kampot, Suzanne Karpelès, who used to work in Bangkok, knew the princesses well, and was mandated by EFEO to assist in the journey, welcomed them. The Prince is impressed by the road to Phnom Penh (“smooth driving, four hours”), less by a visit to the zoo (although he notes that he’s never seen a tiger that big), lunches and dines with “Resident Superieur Baudoin” [1] [with a siesta after lunch, “a tradition that French colonists keeps in the same way as the Dutch), but before that there is the visit to the Royal palace and an audience by King Sisowath (1840−1927). And that is when Prince Damrong fathoms the complexity of Cambodia-Siam shared cultural heritage.

Remembering King Mongkut of Siam [Rama IV] — Damrong’s father — with King Sisowath, who had lived in exile in Bangkok in the 1860s, “we felt like relatives.” Admiring artefacts “created at the time when the Khmer were very powerful”, Prince Damrong starts to distinguish in his relation the “Khom” (ขอม in Thai, referring to all subjects of the Ancient Khmer empire) from the “Khmer” (ขมร in Thai, the people of Cambodia). Describing the Royal Palace of Phnom Penh, he notes that “the construction of this palace began at the beginning of King Rama IV’s reign, King Norodom had come to live in Bangkok, and like the Grand Palace in Bangkok, he built this one as a fortress and a royal palace, small in size”. About the new Throne Hall, he opines that “it should have been done better than this”, with the French architects “not following the legendary Cambodian building techniques.” And he concludes: “In fact, it is an imitation of the Thai model, which came from Bangkok when King Norodom saw it there as mentioned before. […] It is important to think that Khmer things are similar to Thai things.”

When he visits the Phnom Penh Museum and the “Ecole des arts cambodgiens” [School of Khmer Arts] founded by George Groslier — with “Princess Malika, a daughter of King Norodom who have been to Bangkok and whom we were familiar with before” -, Prince Damrong is struck by the fact that “the French director selects examples of Khmer craftsmanship, both ancient and new, for about 200 students, men and women, who practice various handicrafts, from drawing and writing, as well as craftsmanship, goldsmithing, carpentry, and weaving.” These copies, along with “new items in silver and marble”, are then sold in a room of the museum, and “it’s the best place to to buy Khmer things.”

As Alexandra Denes remarked in her 2022 essay “A Siamese Prince Journeys to Angkor: Encounters with a Shared Heritage”, “Prince Damrong also noticed that unlike in Thailand, where Khmer bronzes were plentiful, the collection [of the museum] in Phnom Penh had few good examples of bronze sculpture from the Angkorian period, and he mentioned that people in Phnom Penh attributed this dearth to the fact that Siam had pillaged all the ancient Khmer bronzes. Even though he made a note of the fact that the Khmer blamed the Thais for having stolen their bronzes, nothing in his language registered the least indication of remorse for Siam’s appropriation of these sacred objects that had once belonged to the Khmer. On the contrary, by pointing out the absence of these bronzes in Phnom Penh and their presence in Bangkok, Damrong was expressing the Siamese court’s historical authority and power over the Khmer as determined by a precolonial logic described above, wherein a king’s possession of certain powerful and magical objects was the basis of asserting political supremacy over rival courts and tributary states.”

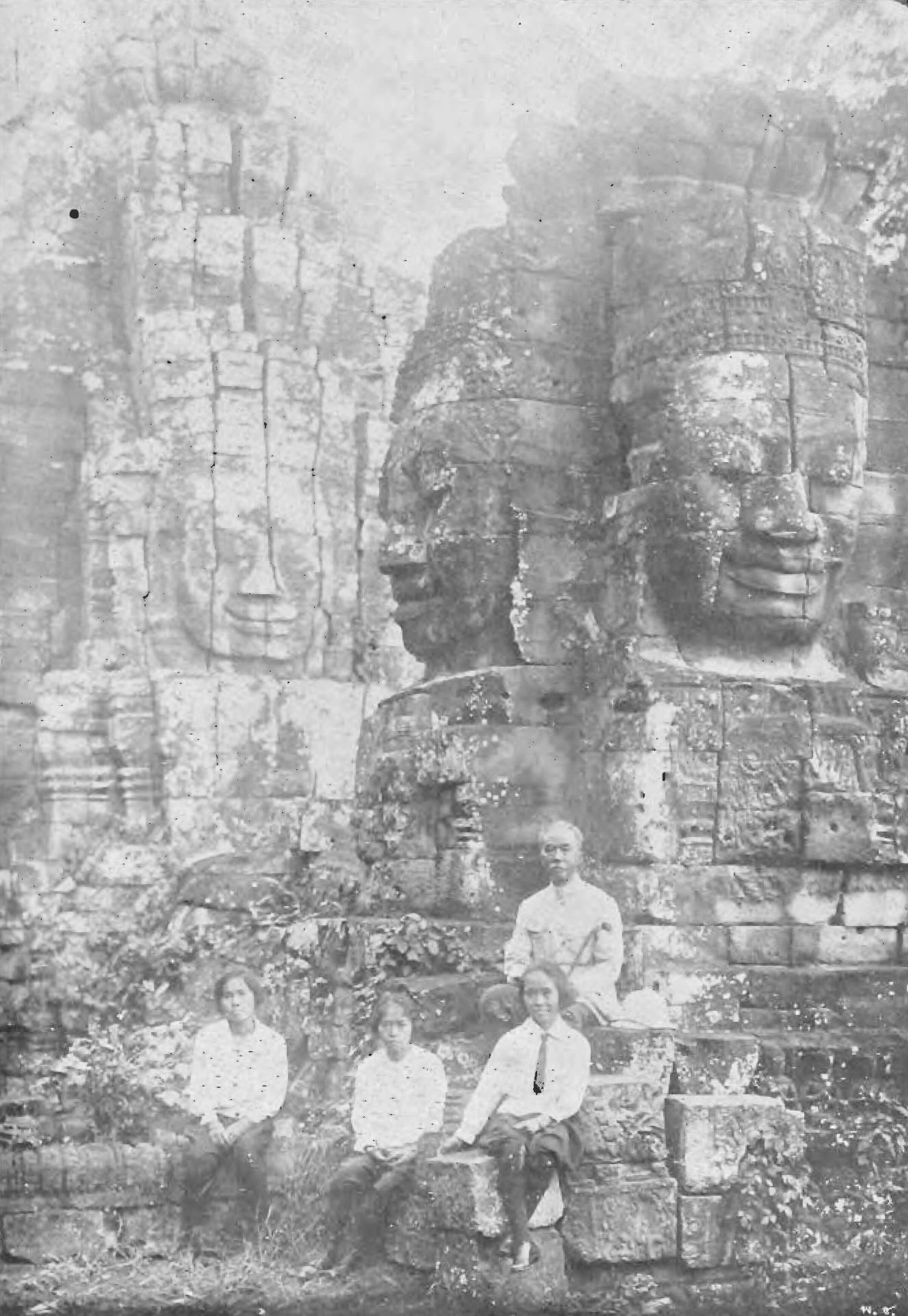

And then, seventeen years after Siam retroceded the provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap to French-ruled Cambodia, three years after King Sisowath welcomed there Marechal Joffre with dancers, elephants and parades, Prince Damrong makes his scientific pilgrimage to Angkor. Arrived at the Bungalow d’Angkor on 21 November 1924, he notes in this diary-travelogue-nirat: “It’s almost dusk already. I could only offer my eyes to admire Angkor Wat from the hotel, but still haven’t been able to go up.” And then, the day after, it is like pure emotion overcomes political misgivings and archaeological curiosity: “I will not be able to truly describe it. I will only tell it when it comes. Really saw Angkor Wat How did you feel that it was different from what you had expected before? That is, it was bigger than what you expected. It looked more elegant than you expected. Moreover, it is admirable that the technician who thought of the plan for Angkor Wat was so clever that he captured the hearts of the viewers.”

In his book, and in remarks related to the 1924 below, Prince Damrong let out some indications on his intellectual and emotional adjustement to the new realities of mainland Southeast Asia. As an archaeologist himself, he was well aware of the historic significance of the remains of Khmer architecture in Cambodia, and also in Siam. He was a great admirer of George Coedes’ and Henri Marchal’s work, and he had taken full measure of the importance of Khmer architecture in Siam when he had welcomed Etienne Lunet de Lajonquiere at the turn of the 20th century, at the time the French explorer was preparing his inventory of Khmer monuments in the Siamese provinces.

Some authors have attributed Damrong’s wish to see Angkor to the “Angkor fad” of the 1920s. He “wished to join the growing throngs of visitors from the metropole to witness the wonders of Angkor for himself”, suggests Alexandra Denes (op.cit.). There must be another ulterior motive to this journey, during which he saw the “modern Khmer” people both as mimickers of every thing Siamese and as potential perpetuators of the Angkorian tradition.

As a Siamese statesman, he seem to start to come to terms with the idea that Cambodian royals are not only “relatives” and former vassals, but could develop some national identity within the framework of the French Protectorate. As an archaeologist and historian, he balks at the suggestion that Angkor was ruined by the Siamese invasions, while reckoning that neither the Siamese nor the Cambodians have the financial and technical means to stop the decaying of the monuments as the French do.

As a learned researcher, Damrong realizes, both in Phnom Penh Royal Palace and in Angkor, that time has come to reconsider the very status of all these objects, statues, swords: do they still belong to the Siamese overlord, or are they something else? Are we still in an era when “royal looters dislodged select images from their customary positions and employed them to articulate political claims in a rhetoric of objects whose principal themes were victory and defeat, autonomy and subjugation, dominance and subordination”, to quote Richard H. Davis [Lives of Indian Images, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1997, repub. 1999 ISBN 0−691−00520−6, p 54]? Can Thai and Khmer people share a cultural heritage in fairness when the latter are still lacking the structure of a nation-state?

“Nirat”, not mere travelogue, we have remarked earlier. Prince Damrong’s book exactly follows the fixed form of the nirat: “In the introduction, the poet praises the glory of their place of origin. In the journey part, which is the most important, the poet gives details on the excursion, usually by listing the names of the places in the itinerary of the journey while associating those places with the poet’s emotional expressions of melancholy from love separation and nostalgic recollection of his beloved. In the conclusion, the poet might refer to literary characters who also suffer from love separation or leave a message that the poetry is intended to be sent to his loved one.” [Nutcha Suwanmalee, op.cit.]

Consider the last sentences in the book:

อันผู้ที่ไปทางไกล ดูเหมือนจะไม่มีเวลาไหนที่ชื่นใจยิ่งกว่าเมื่อ กลับมาเห็นหน้าญาติมิตร์ วันนี้ได้เห็นญาติมิตร์มีแก่ใจไปรับมากด้วย กัน ที่ลงไปรับถึงในเรือก็มี ที่คอยรับอยู่บนบกก็มาก รู้สึกยินดีและ ขอบคุณเป็นอย่างยิ่ง ขออำนวยพรให้มีความเจริญสุขสถาพรางทุกท่าน เทอญ สิ้นเรื่องนิราสนครวัดเพียงเท่านี้ [“For those who have traveled far, there seems to be no time when they are happier than when they return to see their relatives and friends. Today I saw that many of them were willing to come and greet us, some stepping on the boat, and many waiting on the pier to receive us. I feel very happy and grateful. May I bless you all with happiness and prosperity. This concludes the story of Nirat Angkor Wat.”]

Typical nirat ending, but in this case we are left to wander: was not Angkor also the “beloved” in this journey, and was this visit the trigger for a complex, intimate realization that the Siamese prince-archaeologist-statesman had to separate himself from Angkor?

Angkor from a Siamese Point of View, Address given before the Siam Society on July 28th 1925, by the Vice-Patron, HRH Prince Damrong Rajanubhab. [Journal of Siam Society XXI, 1925, p 141- ]

The conference was illustrated by a “lantern slide” screening of nine plates, four of which made from photos displayed in Nirat Nakhon Wat. “When we visited the monuments, some of my friends as well as myself, were able to take a few photographs, some of which, together with other photographs taken from other places, were made into lantern slides, which Mr. R. Wening has kindly undertaken to operate on the screen for you to-night, at the Siam Society conference on 28 July 1925 in Bangkok.” In his remarks, Prince Damrong made the following comments:

Angkorean Toponymy: “The so-called Angkor Monuments are scattered about both in the citadel and outside, just as our monasteries are here. Originally there must have been names to every one of them, but as they became ruined and deserted, they gradually lost their identities. The names by which they are now known are mostly local modern names. In many cases the French have only recently discovered their original names, such for instance as Bayon, the most important of the Angkor Monurnent, which has only lately been identified with “Yasodharagiri” (the Hill of Yasodhara) ; and another sanctuary near the Royal Palace, which has hitherto been called “Bapuon ”, has been identified as “Suvarnagiri” (‘The Golden Hill’). However, these will probably, like “Angkor”, continue to be known by their more familiar names, which have been so long in use.” [p 142]

Origin of the Khmer people: “In dealing with the history of these Khmer monuments, it is well to have in mind the origin and history of this famous race. According to researches, the Peninsula of Indo-China was inhabited by three different races, more or less resembling one another ethnologically as well as philologically. One was the Mon, or Talaing, inhabiting the borders of the Bay of Bengal and the southern part of the valley of the Irawadi ; another, Lao or Lawa, in the valley of the Menarn, spreading right up beyond the plateau to the East; and a third, Khmer or Khom, in the lowlands of the South-East near the extremity of the Peninsula. Even before the dawn of the Christian Era, there had been Indian colonists settling in Indo-China, some of them perhaps as long ago as the seventh or eighth century before Christ. They were probably traders who came and went away after having made their living, and then there would he others who settled down for good. There were in all likelihood two distinct streams of immigration; one’ coming from Central India by an overland and sea route along the coast of the Bay of Bengal as far as the River Salwin, and thus, penetrating the range of mountains to the east, crossing the Menam and finally reaching Cambodia from her Western boundary; and the other coming from Southern India by the sea route, passing Sumatra and Java, entering the Mekhong and settling down in Cambodia, eventually reaching the Lao country to the north.” [p 142 – 3]

Uncompleted monuments: “There is one curious fact that no Khmer re!igious monuments, whether large or small, were ever completed. I first noticed this in the case of Khmer monuments in Siam, such as those of Bimai [Phimai], where one can easily recognise the traces of non-completion. Other monuments bear the same testimony. I made further observations at Angkor Wat with the same result. I then recollected an old tradition with us here in Siam that whoever builds a monastery should leave something to his posterity to complete, otherwise he, too, completes his own life! We may possibly, then, have got this idea from the Khmer, though of course the formation of such an idea is not likely before a nation has spent the energy of its life. The more likely reason is that these monuments were conceived on such a grand scale, that they necessarily took more than a single lifetime to complete. Therefore the construction of the monument would conveniently pass through three probable stages, first, just enough would be built for sacrificial purposes ; then exterior carvings would be added if: the builder were still living; last of all, the interior engraving more often than not would be left to a later generation to complete. [p 148 – 9]

Ruined by whom? “I wish to draw your attention to a certain contention found in many works on Angkor by western scholars, who attribute the ruin of these mighty cities and monuments to the Siamese invasions of Cambodia, almost implying that those monuments would have remained in perfect condition even to these days, had it not been for us. After seeing them, I could not help wondering whether after all they would have so remained even there had been no invasion. One must not forget that the Cambodians changed their capital more than ten times. But, even if Angkor had remained their Capital without interruption down to the present day, I still doubt if they would have been able to preserve those monuments in good condition. In Bangkok today, in what one may call a period at the height of prosperity, we are nevertheless unable to keep even in fair condition all our sanctuaries-even though they are far fewer in number and smaller in every way than those of Angkor. As I have shown above, when explain- ing the apparent changes in the religion of these monuments, there was need already, while the Khmer power was still flourishing, of repairs. How much more so would have been the case when Khmer power waned and declined. Even the Cathedral of St. Paul’s in London, built long after Angkor, is in need of repairs, and I see in the papers that a big subscription of over £250,000 is being started. It makes me think of the ways and means wherewith Bayon and Angkor Wat could have been kept even in fair condition, not to mention other monuments, of which Angkor Thom itself possesses something like thirty or forty. In any case, I think we all owe a debt of gratitude to the French for trying their best to clear and to preserve those monuments for us, as a result of which, I am sure, we shall be able to study more of them as time goes on.” [p 151 – 2]

[1] François Marius Baudoin (31 Dec. 1867, Nice — ?), Résident-Supérieur of Cambodia from 1911 to 1926, interim Governor-General of Indochina in 1922 – 1924. After joining the French Ministry of Finances in 1887, he was sent to Indochina as “commis de résidence” in 1888, reaching the top of the colonial administration in Cambodia. He was representing France at the inauguration of Musee Albert Sarraut (now National Museum of Cambodia) in April 1920.

Nicknamed “triste héros du Bokor” [sad hero of the Bokor] after ordering to build the road to the station-palace at the cost of hundreds of dead Cambodian workers, Baudoin was obsessed with the project of a “station climatique” at the top of Phnom Bokor, he pushed for building a mountain road, using prisoners as forced laborers. The hilltop palace was inaugurated on 14 Feb. 1925, costing the life to 881 “coolies” according to a confidential report from the Minister of the Colonies — much likely close to 2,000. Admitted to retirement in 1926, he brought to France two sons of King Sisowath Monivong, Princes Sisowath Monireth and Sisowath Monipong, for them to further their higher education.

Two rare Baudoin’s photo-portraits, 1) National Archive of Cambodia (NCA), 2) medaillion, along with King Sisowath in the Throne Hall, Prince Monipong and the Council of Ministers (source: Teston, Indochine Moderne).

Tags: Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm, Bayon, Thai studies, Siam, Phnom Penh Royal Palace, Prince Damrong, King Sisowath I, EFEO, French Protectorate, Bokor

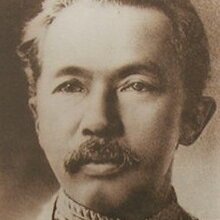

Prince Tisavarakumarn, the Prince Damrong Rajanubhab (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าดิศวรกุมาร กรมพระยาดำรงราชานุภาพ) (21 June 1862, Bangkok, Kingdom of Siam – 1 Dec. 1943, Penang, Malaya?), known as Prince Damrong, a reformer, founder of the modern Thai educational system and provincial administration, and a self-taught historian who has been called ‘the father of Siamese history.’

A son of King Mongkut (Rama IV) with Consort Chum (เจ้าจอมมารดาชุ่ม, Chao Chom Manda Chum), a younger brother of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), Prince Damrong served as Minister of the North, Minister of Interior, Chief of the Supreme State Councul, and was the first president of the Royal Institute of Thailand. His interest in history gave birth to the “Damrong school” which, according to Thai historian Nithi Aeusrivongse, combined “the legacy of the royal chronicle with history as written in the West during the nineteenth century, creating a royal/national history to serve the modern Thai state under the absolute monarchy.”

Since his early education by Francis George Patterson, a special English instructor hired by Rama V to tutor some

of the princes, Prince Damrong developed an interest in the world outside Thailand, touring European and Russian courts, and India.He also spent two lenten periods studying in the Buddhist Order as a novice and as a bhikkhu. To his military education as a cadet in the Military Pages Corps, he added an interest in public health, “directing the construction of Siriraj Hospital during 1887 – 88 and assisting in the subsequent opening of the first medical school in the kingdom”, according to Kennon Breazeale (“A transition in historical writing: The Works of Prince Damrong Rachanup”, Journal of Siam Studies (JSS), 059 – 2, 1971,p 27).

As Minister of Interior, Prince Damrong supervised the first archaeological surveys in Siamese provinces. In the southern part of the Kingdom (not including Cambodian Angkor and Battambang provinces, annexed until 1907), he supported the prospections led by Etienne Lunet de Lajonquiere, who visited Nakhon Pathom several times from 1904 to 1908, at a time the latter was completing his Inventory of Cambodian monuments.

Prince Damrong worked closely with George Cœdès in sorting out the inscriptions and historical sequencing of ancient Thailand. The Khmerologist had been assigned by EFEO Director Claude-Eugène Maitre to the Bangkok Royal Library in 1918, so he could further his comparative studies in the Dvāravatī civilization, and in the Srivijaya kingdoms of Sumatra. Coedès returned to Hanoi in 1929, when he became director of the EFEO school. After retiring as Minister of the Interior in 1915, Damrong was appointed Chairman of the Wachirayan National Library by King Vajiravudh (Rama VI, r. 1910 – 1925), and took on the responsibilities of Director of the Royal Academy and the National Museum.

In the framework of his own research on the history of Siam (Thailand) and Southeast Asia, Prince Damrong studied Khmer history and visited Angkor (in 1924) and Preah Vihear (in 1930) both times along with his daughters. He wrote a brief history of Angkor, Nirat Nakhon Wat (Journey to Angkor Wat, first published in 1925).

After the 1932 coup in Bangkok, Prince Damrong, in favor of the absolute monarchy, fled to Penang, Malaysia. Some sources claimed he died there in 1943, while his great grandson, Pannada Diskul (b. 26 Aug. 1956), asserted that he passed away in the same building he had been arrested in 1932, the Varadis (pron. Waradit) Palace, a quaint Chinese-style townhouse away from Lan Luang Road in old Bangkok, In 1962, Prince Damrong Rachanupab was awarded the UNESCO award of the World’s Outstanding Personality, the first for a Thai.

Restored in 1996 — on the 53rd anniversary of Prince Damrong’s death — and converted into the Prince Damrong Rachanupab Museum and Library, Varadis Palace holds a collection of 7,000 books in Thai and English.

bm တလိုင်း talaing | kh តាឡាងិ talangi | ch 得楞 To-leng | [?] sk तैलङ्ग Tailaṅga "the Tailanga country"

Talaing is one of the Burmese names referring to the Mon people, and used during the British colonial era along with Peguan, from Pegu, the ancient capital of Lower Myanmar.

While the word has been found in local inscriptions dating back to the reign of King Anawrata (1044-1077 CE), its etymology remains unclear, one hypothesis being it was linked to the Telinga-Kalinga-Karnatak region of southeast India - cf. Sanskrit तैलङ्गः tailaṅgaḥ "inhabitants of Tailanga [Telinga]".

British colonial historians commonly used the words 'Talaing' or 'Peguan' to refer to the Mon people of Burma. For instance, Deputy Commissionner of Burma C.J.F.S. Forbes wrote in 1882: "Burmans are of the Mongolian race, of which the Talaings, Shans, Siamese, and Chinese form also a part. Both their bodily characteristics and their language when compared prove the utter want of connection between the Burman and Rajput races." However, Mon communities have rejected the term for a long time, and it is now considered as pejorative.

Studying Chinese sources from the beginning of the 17th century, Paul Pelliot has proposed that the the To-leng (Tailang) formed a tribe from the 大古喇 "Grand Kou-la [polity], also called 擺古 Pai-kou (Pegu)", were also called 'kola", and joined forces with the Siamese against the Burmese in 1610. According to him, they were dwelling "in the Irawaddy estuary, or perhaps near Martaban" [ancient name of Mottama bm မုတ္တမမြို့, mon Muttama မုဟ်တၟံ, a town in the Thaton District of Mon State, on the west bank of the Thanlwin River (Salween), an important trading center and the capital city of the Martaban Kingdom (later Hanthawaddy Kingdom) from 1287 to 1364.