The Customs of Cambodia [1st English Translation]

by J.G.D. Paul

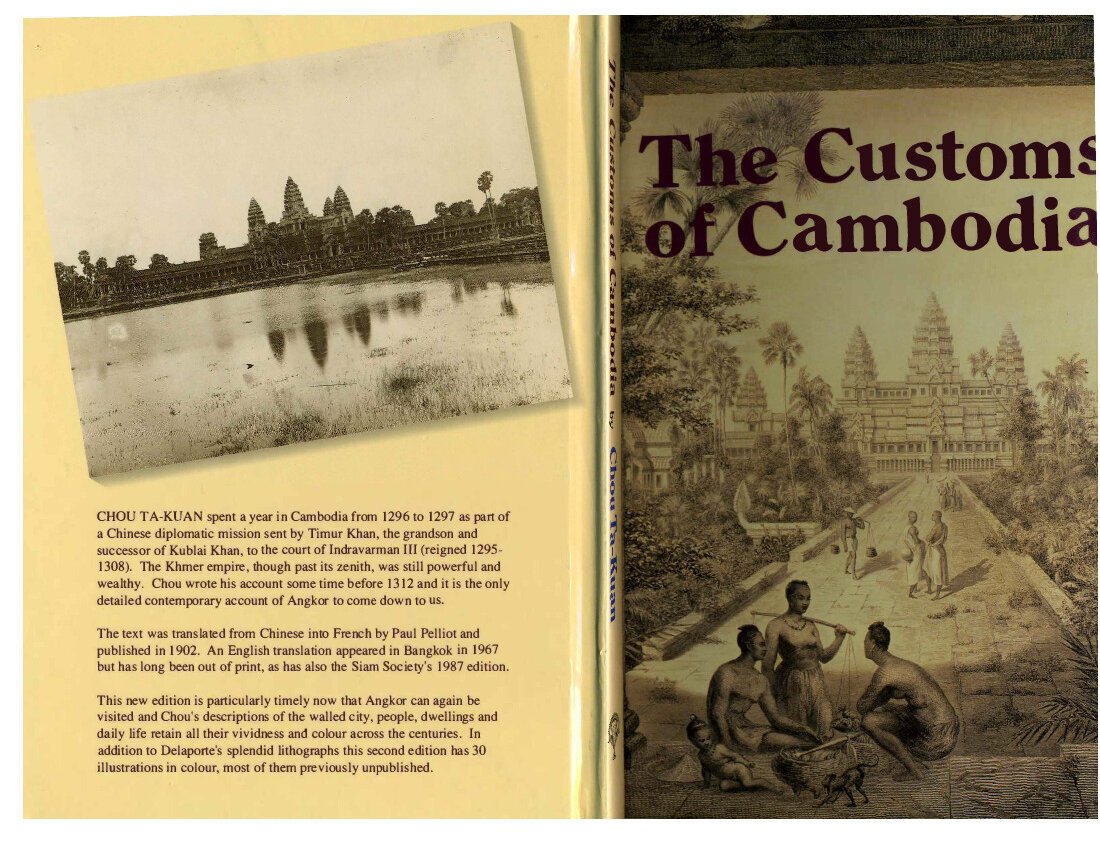

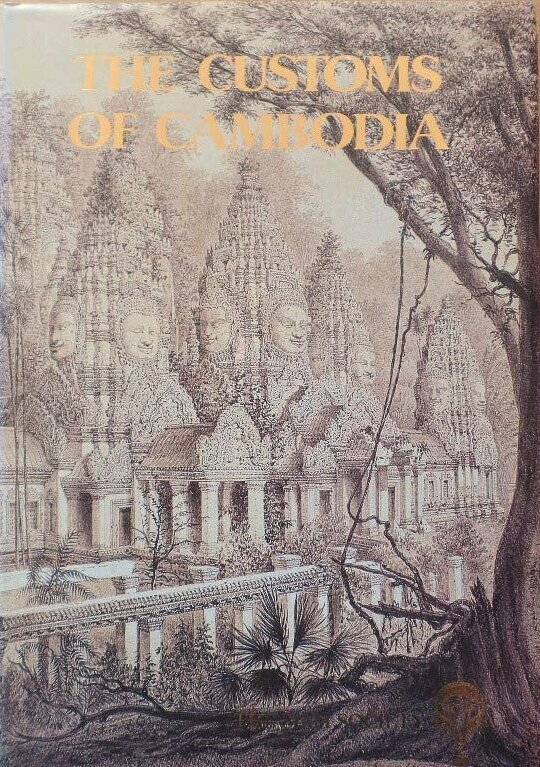

The first ever English translation of Zhou Daguan's celebrated account of Angkor in 1296-7, from Paul Pelliot's 1902 French translation.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Bangkok, The Siam Society.

- Edition

- 2nd ed. from the 1987 edition, with uncredited color photos of Angkor and colorized drawings by Louis Delaporte.

- Published

- 1992

- Author

- J.G.D. Paul

- Pages

- 95

- ISBN

- 974-8359-68-9

pdf 71.8 MB

In 1967, the Social Science Association of Thailand published this translation [under the title Notes on the Customs of Cambodia, a copycat of Paul Pelliot’s 1902 first ever French translation from the Chinese of Zhou Daguan’s account] by enigmatic author John Gilman D’Arcy Paul, an American retired diplomat with strong ties to Thailand. Since it was the first English rendition of this all-important text, the Siam Society thought it fit to publish it it again in 1987, and again in 1992.

On the backcover, the editors noted

This new edition is particularly timely now that Angkor can again be visited [after the 1970 – 1979 civil war, ADB] and Chou’s descriptions of the walled city, people, dwellings and daily life retain all their vividness and colour across the centuries. In addition to [Louis] Delaporte’s splendid lithographs this second edition has 30 illustrations in colour, most of them previously unpublished.

Reviewing Peter Harris’s translation in the Journal of Siam Society (vol 96, 2008), renowned specialist of Cambodia’s modern history Milton Osborne remarked

Until quite recently, it is a fair assumption that most Anglophone readers will have encountered Zhou Daguan

in the translation from French of Paul Pelliot by J. Gilman d’Arcy Paul, first published by the Siam Society in 1967. And, since 2001, these same Anglophone readers have had the opportunity to consult a more up-to-date and elegant rendering of the French by this journal’s editor, Michael Smithies, published again by the Siam Society. Few readers, whether Anglophone or Francophone, will have gained access to Zhou Daguan by returning to the French translation of this work by Paul Pelliot, published in 1902, let alone the first translation from Chinese into French accomplished by Jean-Pierre-Abel Rémusat in 1819. Now, for the first time in over fifty years, Peter Harris has provided us with a translation of Zhou’s text, working directly from Chinese into English. And he has done so with a very detailed accompanying scholarly apparatus that places Zhou Daguan in his place and time, while explaining his reasons for varying his translation from those offered by his predecessors working from French into English. One point to which the translator gives particular emphasis is the fact that Zhou Daguan’s ‘record’, as we have it, is only part of the document he prepared after spending a little less than a year in Cambodia in 1296 – 97.

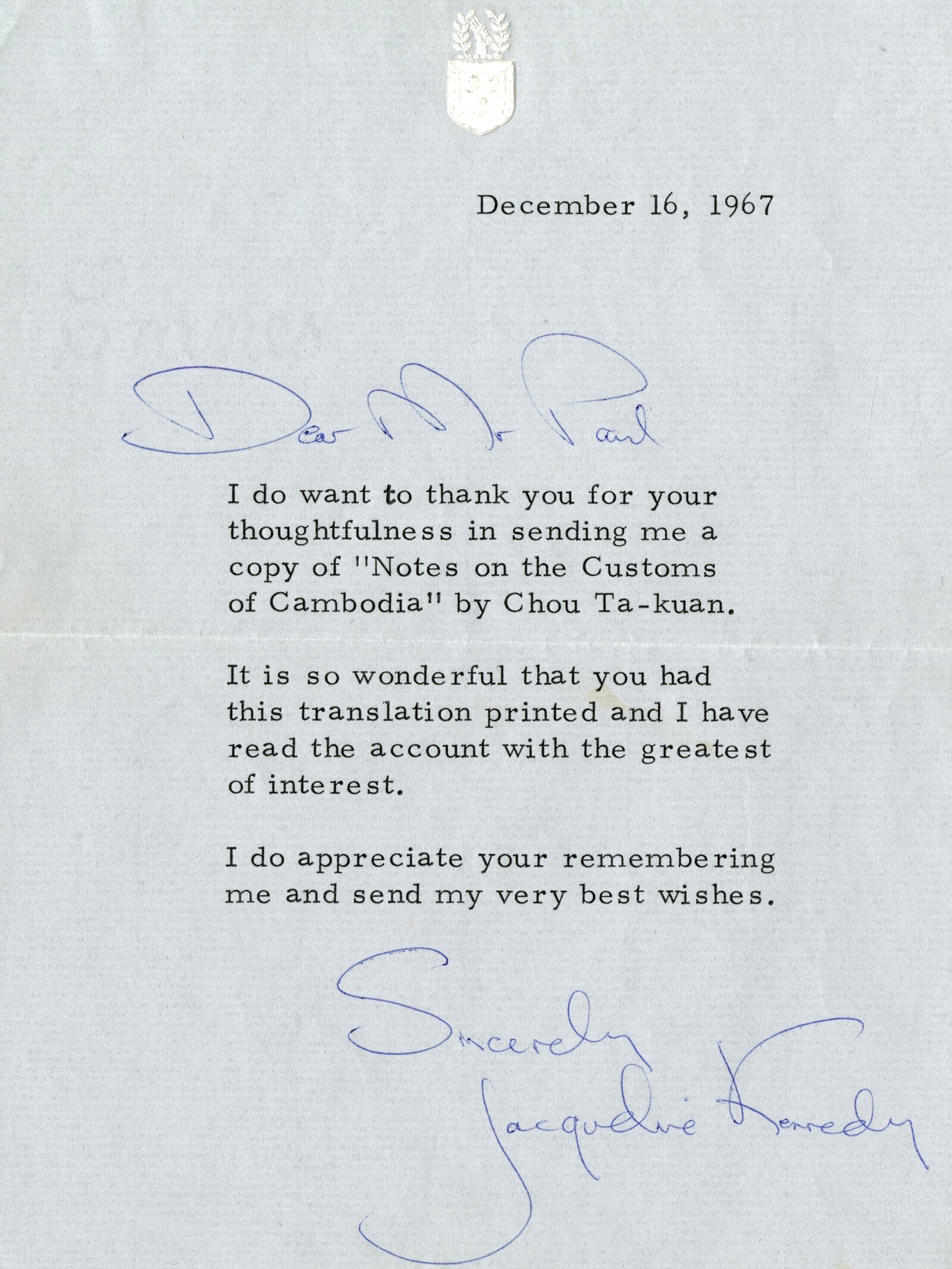

Of the text presented, we only know that the author and the publisher of the first edition received a grant from the Breezewood Foundation, established in Maryland — the same US State the author hailed from — and Thailand in 1955 by A.B. Griswold. We also know that this translation was presented to former US First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy around the time she visited Ankor [Nov. 1967], and she tanked the author for that, especially as she wrote a high-school dissertation on Zhou Daguan in her youth — few were in the know of that detail at the time.4

Apparently, the author wasn’t aware of the fact that Pelliot had left a slightly improved version of his own 1902 work, quite confidentially published in 1951 in Paris. And he opted for not including the abundant notes (Pelliot style!) to his elegant and accurate translation. The few ones he added were certainly not revised by the Thai editors, since we find for instance “uncooked rice (Khmer ranko)”, when he obviously meant អង្ករ, ongko, husked rice.

There are certain quaint English words in this work, such as “peafowl” for “peacock”, or “aborigines” for the people Zhou Daguan called ye ren, “wild, uncivilized people”, the slaves employed at Angkor, which Pelliot translated as “sauvages” and Harris “savages”. In the latter instance, however, the chosen term seems to indicate that Khmer people in Angkor mostly used as slaves local people who weren’t Khmer, nomadic tribes “wandering in the mountains” [“hommes des solitudes montagneuses,” according to Pelliot, moving “from place to place in the mountains” in Harris’ translation].

As a former American diplomat based in Paris in the 1900s and 1910s, his command of French (as well as German and Russian, it seems) was did the job properly. Here after, two samples of translator’s choices, selected from the most discussed parts of the Chinese account:

Chapter 8, the zhentan ceremony

This translation didn’t follow the conventional numbering of Zhou Daguan’s text as reconstituted from numerous Chinese sources. When Harris soberly titles this chapter “Young Girls”, here we have “Maidenhood in Cambodia”:

When a daughter is born to a Cambodian family, it is customary for the parents to express for her the wish: “May the future bring thee a hundred, a thousand husbands!” Daughters of rich parents, from seven to nine years of age (or eleven, in the case of poor people) are handed over to a Buddhist or Taoist priest for deflowering, a ceremony known as chen-t’an. Each year the proper authorities choose a day of the month corresponding to the fourth Chinese moon and let this be known throughout the country. Every family with a daughter ripe for chen-t’an then notifies the authorities, who send a taper bearing on its length a certain mark.

At nightfall on the proper day the candle is lighted, and when it burns down to the mark the moment for chen-t’an has come. A fortnight before this the family will have chosen a priest — Buddhist or Taoist according to their place of residence. The services of the higher class of priests are all engaged in advance by the families of wealth or social prominence, while the poor have no time for making distinctions. The former load the priests with presents of wine, rice, fabrics, silk, areca-nuts, silver plate, in value often reaching one hundred piculs, or two or three hundred ounces in Chinese money. Presents from people of lesser station may be worth thirty or forty piculs, according to the size of the family fortunes. If poor girls find themselves approaching their eleventh birthday without getting together sufficient money to pay the priest, it often happens that generous people of means help with a contribution, which they call “acquiring merit.” A priest is not allowed to perform the ceremony for more than one girl a year, and once he has accepted his fee he cannot pledge himself to initiate a second one.

The night of the ceremony a great feast, with music, is prepared. In front of the girl’s home a platform is erected on which are placed figurines of animals and persons, sometimes ten or more in number, often less. Nothing of this sort is expected of the poor. Following an ancient tradition these figurines remain in place for a week. Next, a procession with palanquins, parasols, and music sets out to fetch the priest. Two pavilions hung with brilliantly coloured silks have been set up; in one of these is seated the priest, the maiden in the other. Words are exchanged between the two, but they can scarely be heard, so deafening is the music, for on such occasions it is lawful to shatter the peace of the night. I have been told that at a given moment the priest enters the maiden’s pavilion and deflowers her with his hand, dropping the first fruits into a vessel of wine. It is said that the father and mother, the relations and neighbors, stain their foreheads with this wine, or even taste it. Some also say that the priest has intercourse with the girl; others deny this. As Chinese are not allowed to witness these proceedings, the exact truth is hard to learn.

At daybreak the priest is escorted back home with palanquins, parasols, and music, after which it is customary to buy the girl back from the priest with presents of silk and other fabrics; otherwise she becomes his property forever and cannot marry. What I saw of these proceedings took place on the sixth night of the fourth moon of the year ting-yu, of the period ta-te (April 28, 1297). Before the ceremony the father, the mother and the daughter had always slept in the same room; afterwards, the room was closed to the young woman, who went wherever she pleased, with no constraint. When it comes to weddings it is the custom to make presents of textiles; this obligation is lightly assumed, however, as bride and groom have often had pre-nuptial intercourse. In this there is seen no cause for shame, or even surprise. The night of the chen-t’an more than ten families often perform the ceremony at the same time, processions of Buddhists and Taoists meeting and crossing in the streets. Everywhere there is the sound of music. [p 17 – 9]

Chapter 6, the men-women who scared and fascinated Zhou Daguan

The “mignons” in Pelliot’s version, correctly identified by Harris as Er xing ren, “people with two forms or appearance, and in the Thai translation as katoey, plainly transgender people as we would have it nowadays, find here a naming that remains us that the author graduated from an Ivy League university:

In the market place groups of ten or more catamites are to be seen every day, making efforts to catch the attention of the Chinese in the hope of rich presents. A revolting, unworthy custom, this! [p 15]

κιναίδων in ancient Greece, catamitus in antique Rome, referred to a pubescent boy as intimate companion of an older male, in reference to Ganymede, the Trojan youth abducted by Zeus to be his companion and cupbearer in the Greek mythology. In modern days, it is a derogatory name for a passive partner in an homosexual relationship. Definitely not the boisterous youths Zhou Daguan saw on Angkor markets…

Tags: Zhou Daguan, translations, JSS, American travelers, 1960s, women, sexuality

About the Author

J.G.D. Paul

John Gilman D’Arcy Paul [or J.G. D’Arcy Paul or J.Gilman D’Arcy Paul or J.G.D. Paul or John Paul] (31 Jan. 1887, Baltimore, Maryland — 12 Jan. 1972, Gilford, MD, USA) was an American diplomat, patron of the arts, globetrotter and landowner in Maryland, USA, who authored the first English translation (from Paul Pelliot’s French translation) of Zhou Daguan’s Customs of Cambodia, published in Bangkok in 1967 (2nd ed. 1987, 3d ed. 1992).

A son of D’Arcy Paul (1854 – 1890) and Charlotte Abbott Gilman (1861 – 1954) — hence the uncommon piling-up of surnames -, J.G.D. Paul majored in Russian at Harvard University in 1908 — he had already started his diplomatic career as private secretary to John W. Garrett, US ambassador to Argentina — and served as special attaché to the US Embassy in Paris at the start of WWI, then joining the US Legation at The Hague in 1917 and the US delegation to the Peace Conference in Paris. He was then fluent in German also, as he translated for the first publication in which he was credited, a two-volume sum on secret Austrian treatises (in 1920 – 1).

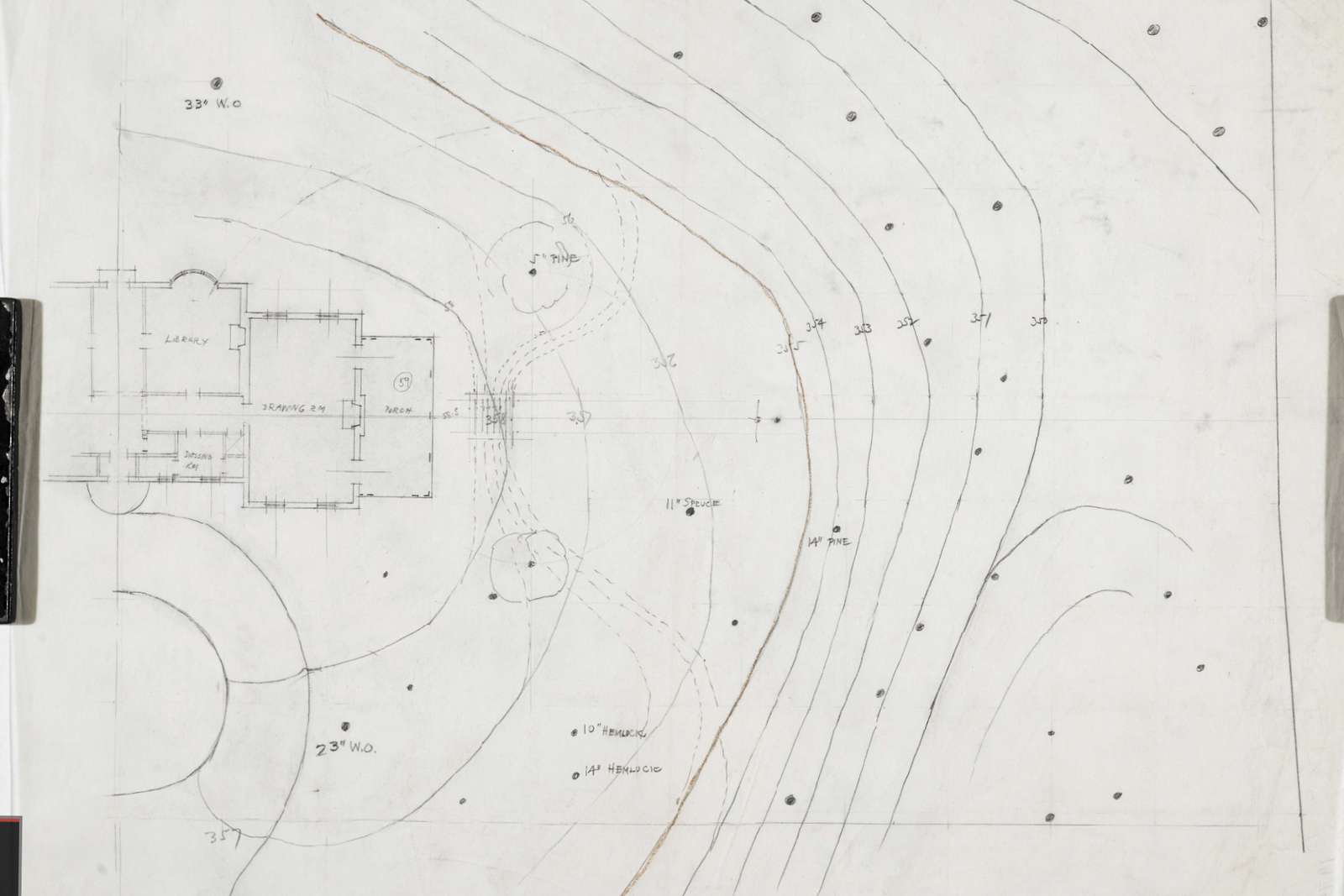

He was assistant editor of The Atlantic Monthly under Ellery Sedgwick in Boston in 1916 – 17, wrote for the Baltimore Evening Sun, and was passionate about historic preservation, leading efforts to restore “Hampton,” the Ridgely family’s Towson estate in Maryland. He also initiated the creation of the Susquehanna State Park on a land he owned near Havre de Grace (Harford County) called Land of Promise. With famous American architect Charles A. Platt (1861−1933), he planned the renovation and extension of the family’s estate house in north Baltimore, “The Woodlands”. He also served for many years as president of the Baltimore Museum of Art, vice president of the Maryland Historical Society, and a trustee of Johns Hopkins University, the Peabody Institute and Peale Museum in Baltimore.

From then, his life is quite an enigma. He was certainly a special service officer during WWII, as he reported on the fate of French prisoners in Nazi-occupied Algeria in 1942, and he was active in several countries after his official retirement in 1957. He lived (or was based?) in Cambodia in the 1950s-1960s, and developed an interest in Zhou Daguan’s 13th century account of Angkor. His English translation was published by Bangkok Siam Society in 1967, yet we couldn’t find his name in the Membership Roll issued by JSS in 1966, nor in 1967 and 1968.

According to then President of the Social Science Association of Thailand Prince Wan Waithayakorn’s foreword to the 1967, edition, “the translator [d’Arcy Paul] is a friend of Mr. A.B. Griswold, a well-known student of Thai art and Thai culture, who has sent us a sum of money on behalf of the Breezewood Foundation for the publication of the document in question.” ADB Input: Alexander Brown Griswold (19 April 1907, Monkton, Maryland, USA — 4 Oct. 1991), an investmenrt banker with the firm Alex, Brown & Sons since 1930 and thenafter, had served in the US Office of Strategic Services [OSS] in Thailand during WWII, and founded in 1955 the Breezewood Foundation, with a collection containing some 300 pieces of Thai, Burmese, Cambodian, Cham, Indian and Indonesian art, donated to the Walters Art Museum (Baltimore) in 1987 and 1992. Some 3,500 photographs representing those artworks have been duplicated and are kept at the University of Michigan Library. As a Southeast Asian art expert, he was mostly self-taught, learning from EFEO researcher George Cœdès, Bangkok National Museum curator Luang Boribal Buribhand, Pierre Dupont and Jean Boisselier, whom he hosted in his Thailand house in 1964.

On purpose or serendipity, J.G.D. Paul had his translation published a few weeks before Jacqueline Kennedy’s historic visit to Cambodia, and he offered a copy to the former US First Lady who kindly replied with a thank-you note on 16 Dec. 1967, a few days after her visit:

The H. Furlong Baldwin Library [through the Maryland Center for History and Culture] keeps his papers, mainly his correspondence with his mother Charlotte Abbott Gilman Paul. The collection “covers the periods when he was away from Baltimore for school, work, and travel. In his letters, he vividly described the people he met and places he visited and was seldom shy in sharing his opinion. The letters from his time in the employ of the United States government discussed the major issues of the time, as well the major players. Locations represented in these letters include Massachusetts, Maine, Guatemala, France, Holland, Cambodia, and more.”

Known Publications

- [contributor as translator from German, with Denys P. Myers (Denys Peter), Archibald Cary Coolidge] Alfred Francis Pribram, The Secret Treaties of Austria-Hungary, 1879 – 1914, Harvard University Press, 2 vols, 1920 – 1921.

- Some gardens and mansions of Maryland; a descriptive guide book for use on the pilgrimage arranged under the auspices of the Federated garden clubs of Maryland, for the benefit of the restoration of the gardens at Stratford, birthplace of General Robert E. Lee, The Barton-Gillet company, May 1930; Federated Garden Clubs of Maryland, nd.

- Notes on the customs of Cambodia, Bangkok, Social Science Association of Thailand Press, 1967; The Siam Society, 1987 and1992.