Visions of Angkor by...John Thomson

by John Thomson

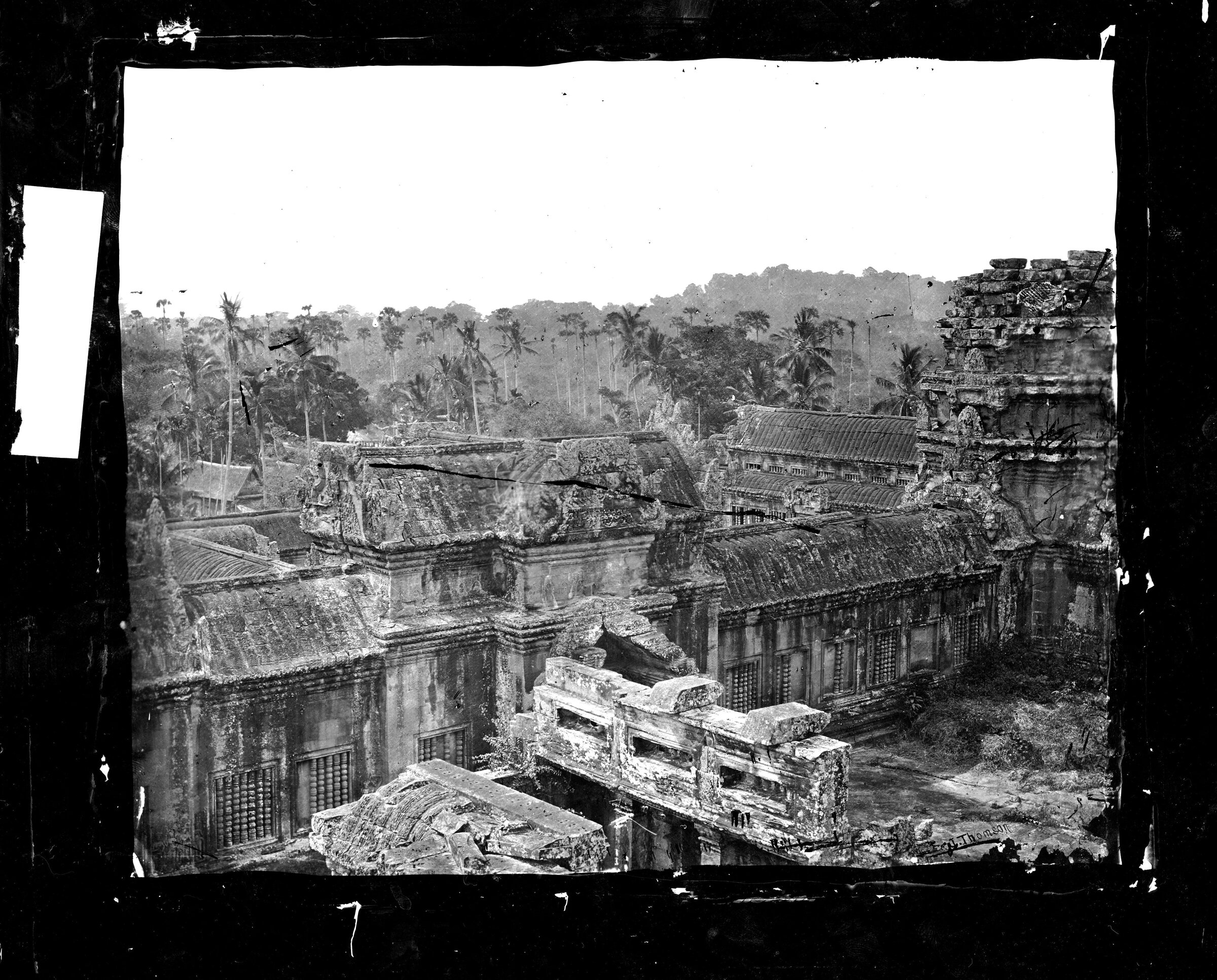

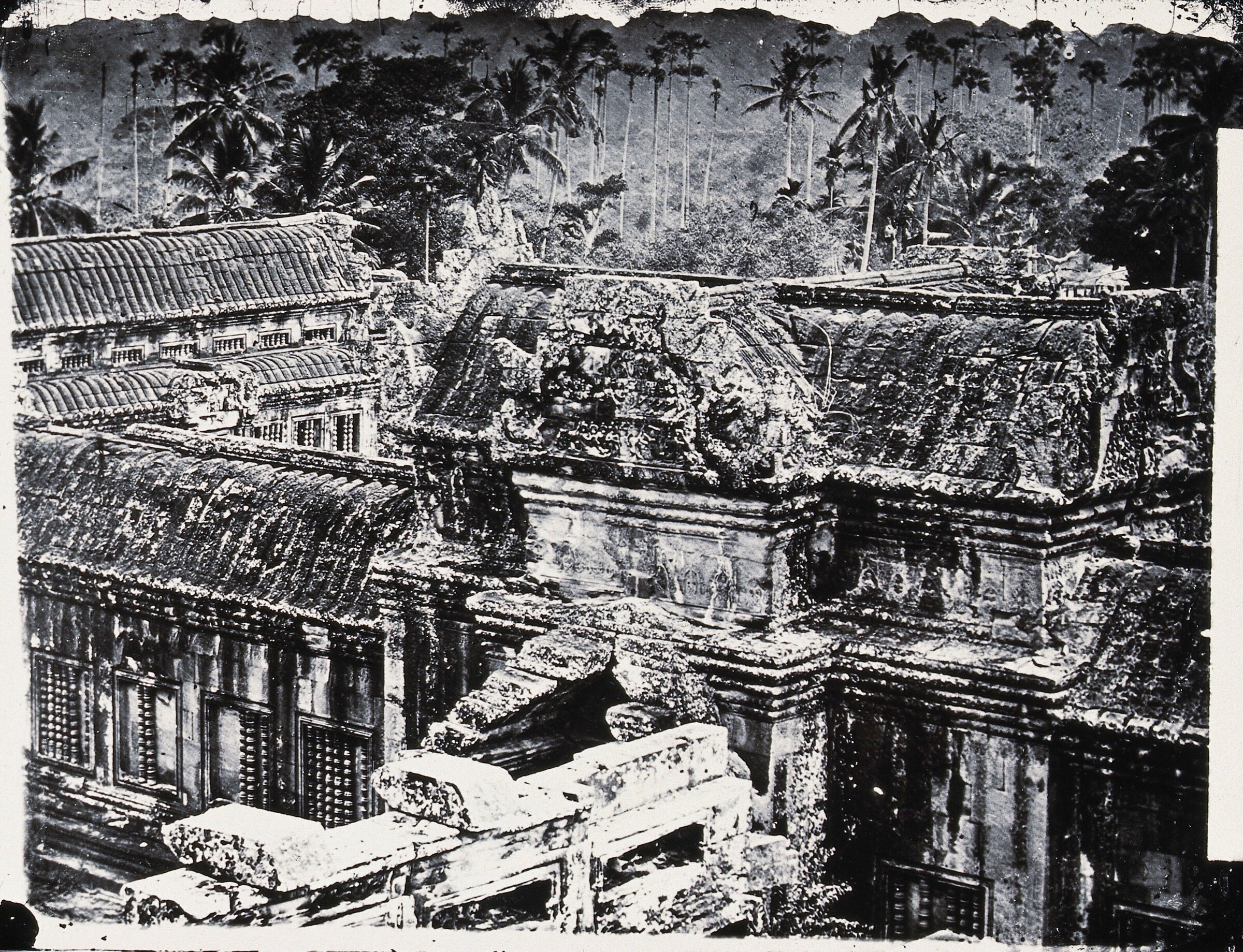

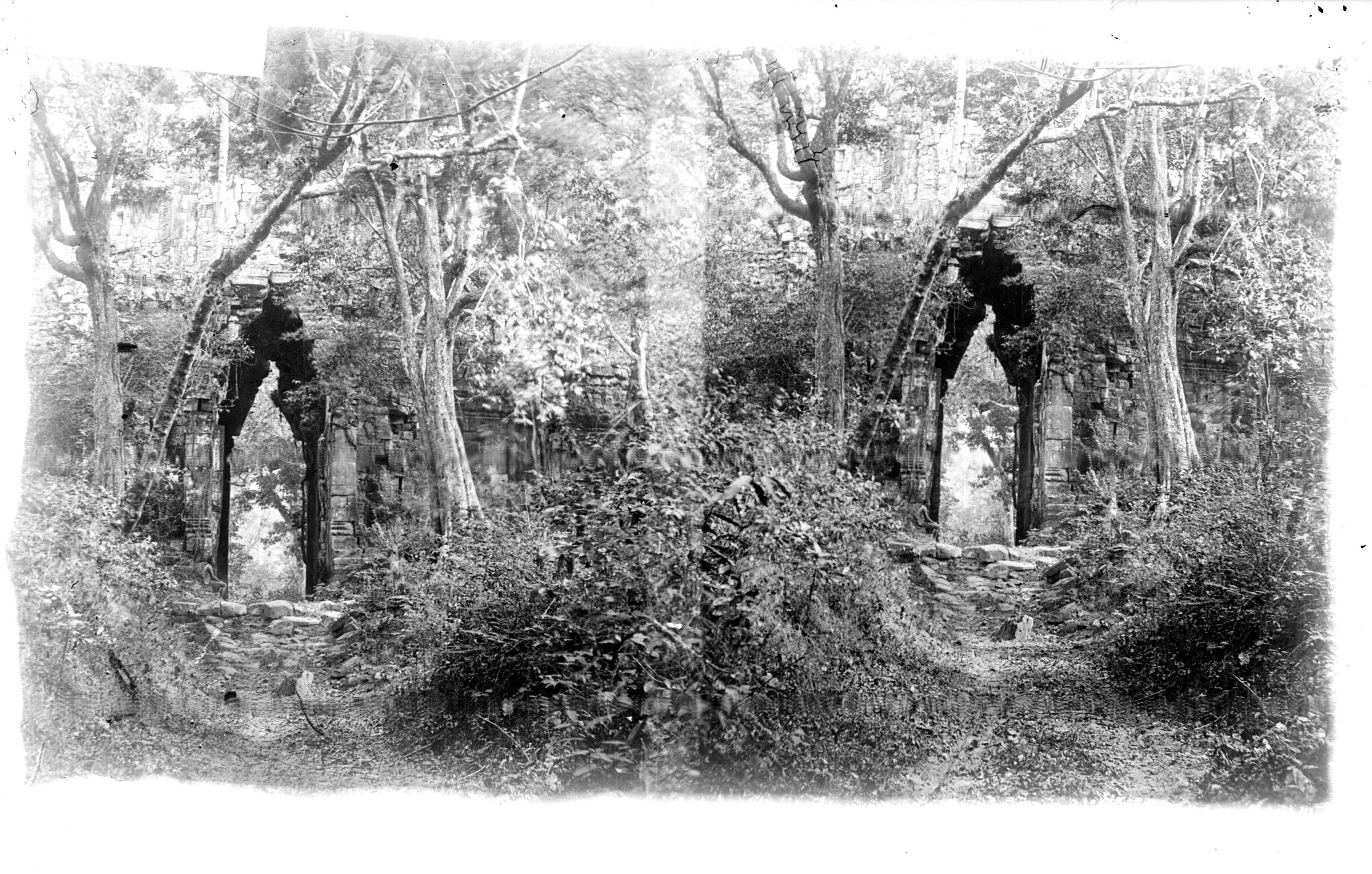

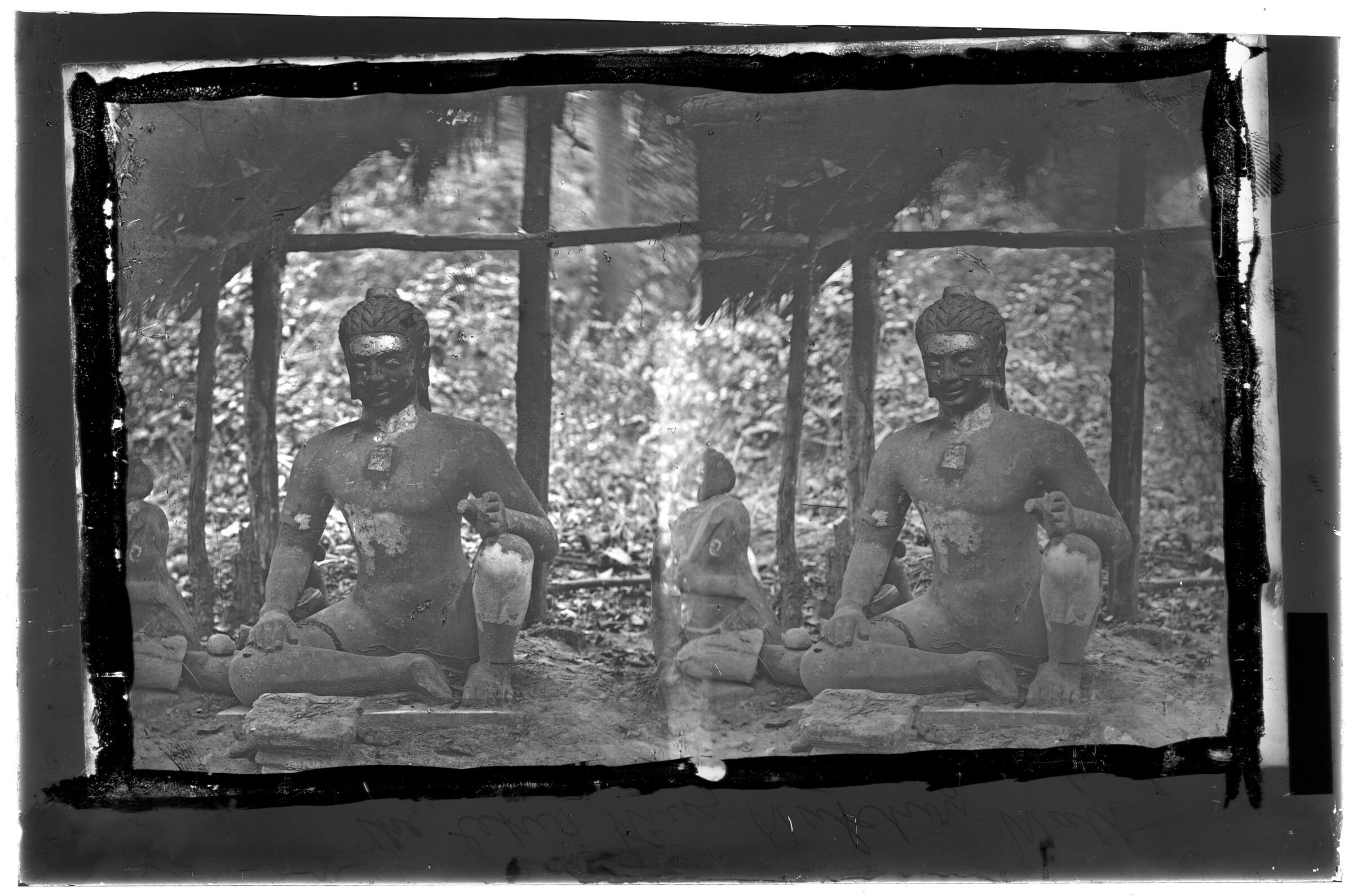

Angkor seen by pioneer photographer John Thomson in 1866.

Published: 1866

Author: John Thomson

Source: Wellcome Library, London (online resources) | National Gallery of Canada | Louis Porter | ADB

In his Straits of Malacca (p. 98 – 100), John Thomson recounted that, back from Cambodia –where he had spent three months, mostly in Angkor — to Bangkok in April 1866,

I presented his majesty [the King of Siam] with a set of my photographs of the Cambodian antiquities [they were about 40 glass photonegative plates, according to Paisarn Piemmettawat in Siam Through the Lenses of John Thomson 1855 – 66], with which he seemed very much astonished. ’ What can I do for you, Mr. Tomo-shun?’ said he. ‘I will give you, if you wish, a free passage to Singapore.’ Perhaps he took me for a ‘yak ’ or evil spirit, and wanted me well out of his dominions. At any rate he may have honestly thought that anyone who would take the trouble to go so far to examine dilapidated specimens of ancient masonry had better be looked upon as insane, and treated as a dangerous character. […] His majesty then asked me if I thought that the ancient temples of Cambodia belonged to Siam. I said I supposed they did, and he promised to give me some information on that subject before I quitted his dominions. Faithful to his word, the King afterwards paid my passage to Singapore, and presented me, in addition, with two golden mangoosteens and a cigar-case elaborately inlaid with gold. He also sent me a letter in English, from which I take the following extract: ‘I beg to take from you a promise that you should state everywhere verbally, or in books, and newspapers, public papers, that those provinces Battabong and Onger, or Nogor Siam, belonged to Siam continually for eighty-four years ago, not interrupted by Cambodian princes or Cochin China. The fortifications of those places were constructed by Siamese Government thirty-three years ago. The Cambodian rulers cannot claim in these provinces, as they have ceded to Siamese authority eighty-four years ago.’

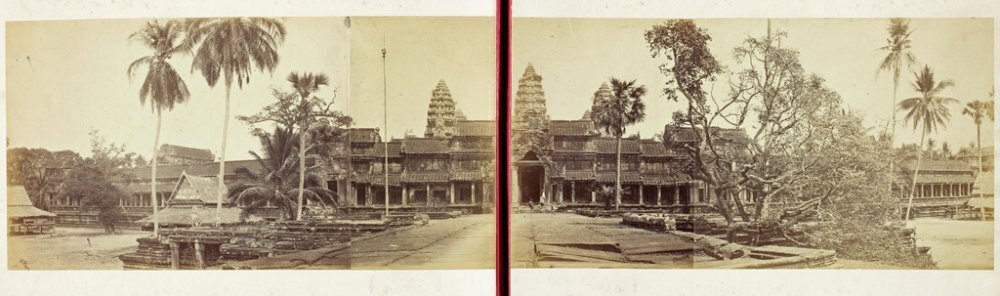

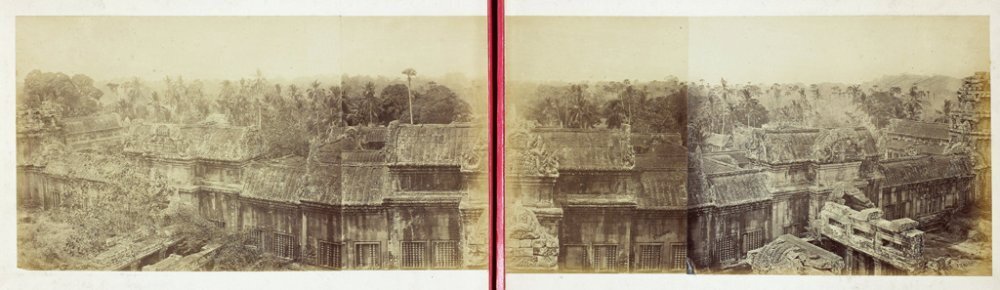

For the first time ever, we share here a structured collection of these photographs that had so much ‘astonished’ — and alarmed — King Mongkut of Siam (r. 1851 – 1868). In the Wellcome collection, Thomson’s work at Angkor Wat and other Khmer temples is scattered amongst the photographer’s plates, negatives, and prints. Here, we have organized each view from the origin to later prints:

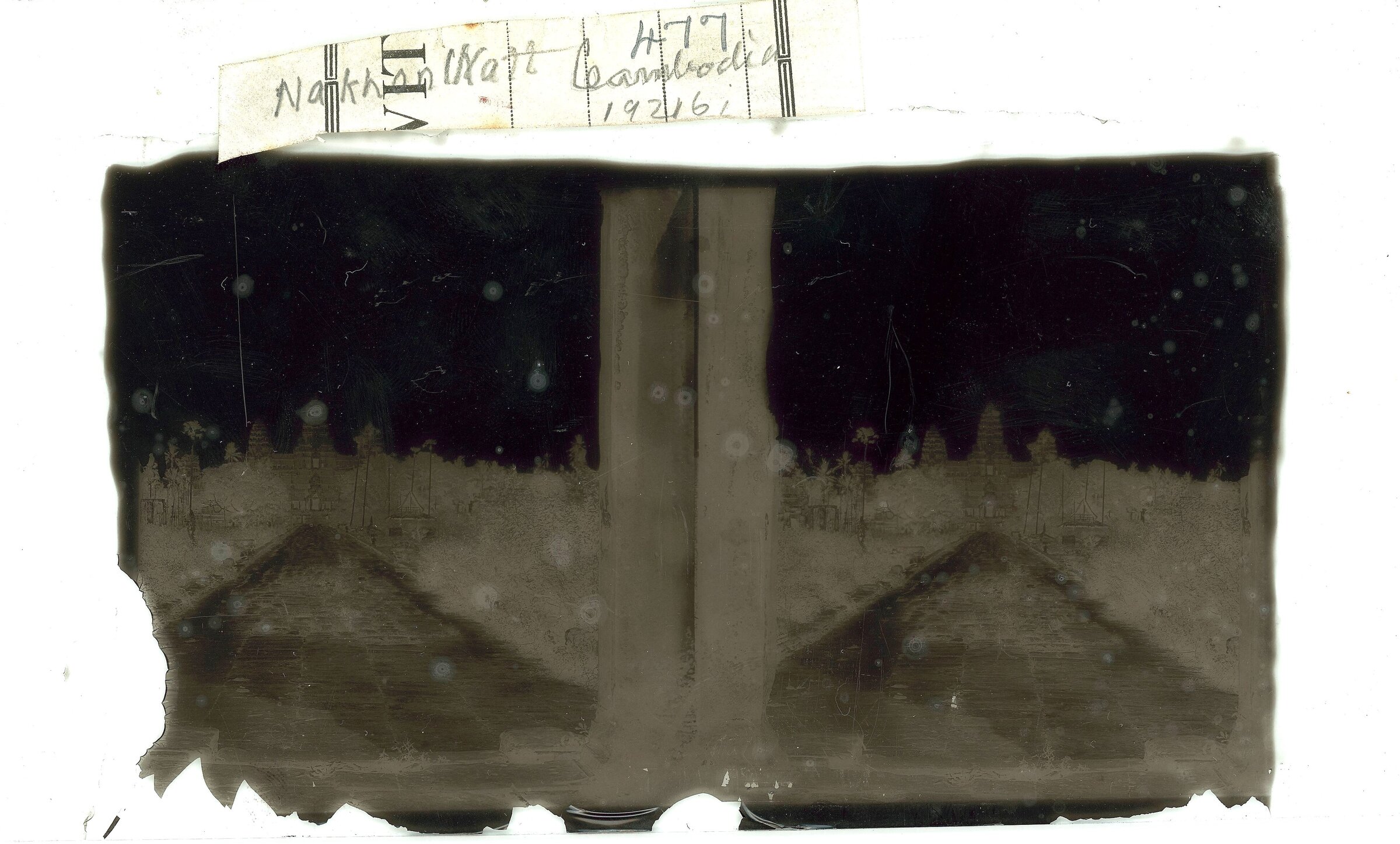

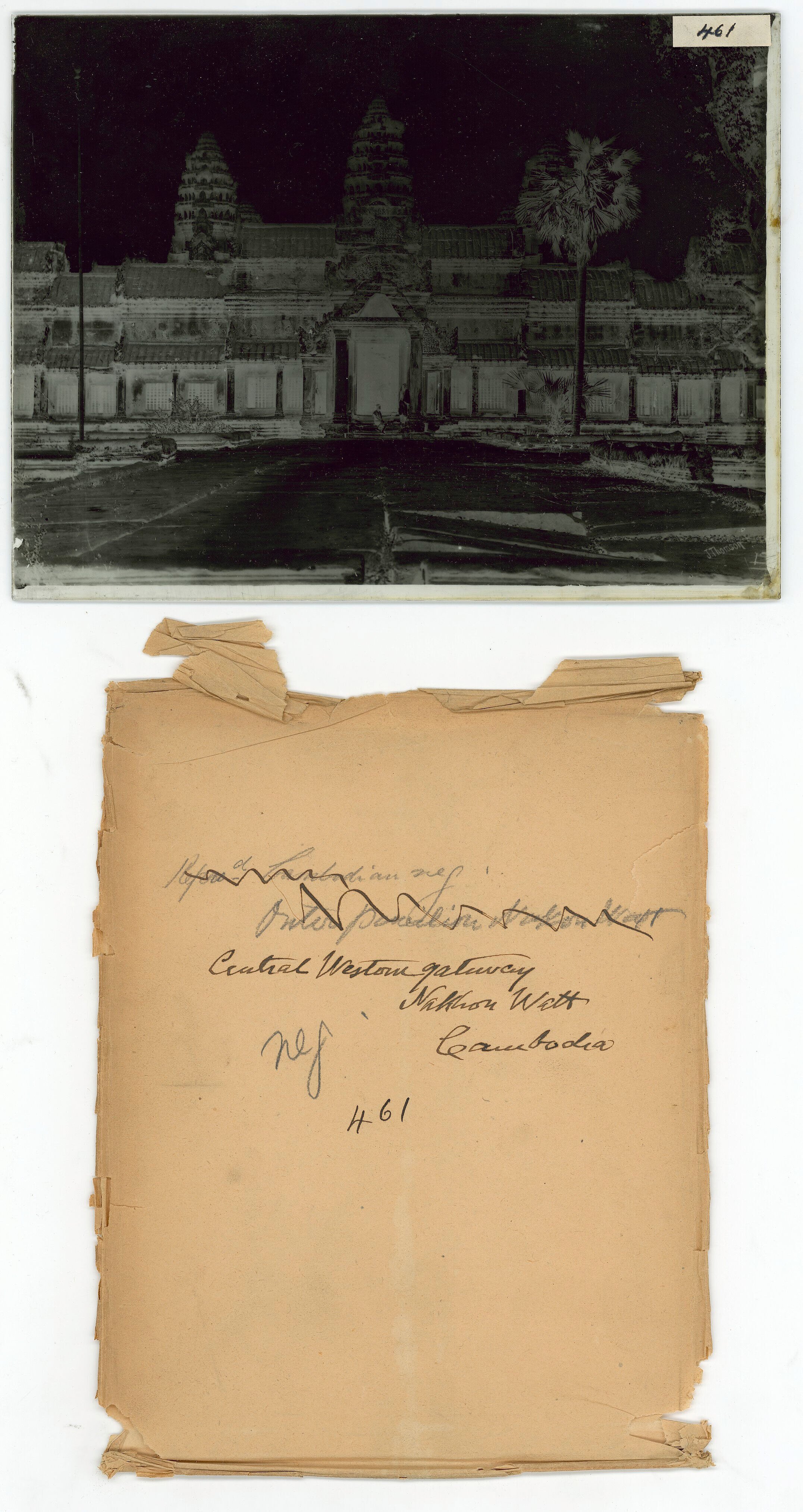

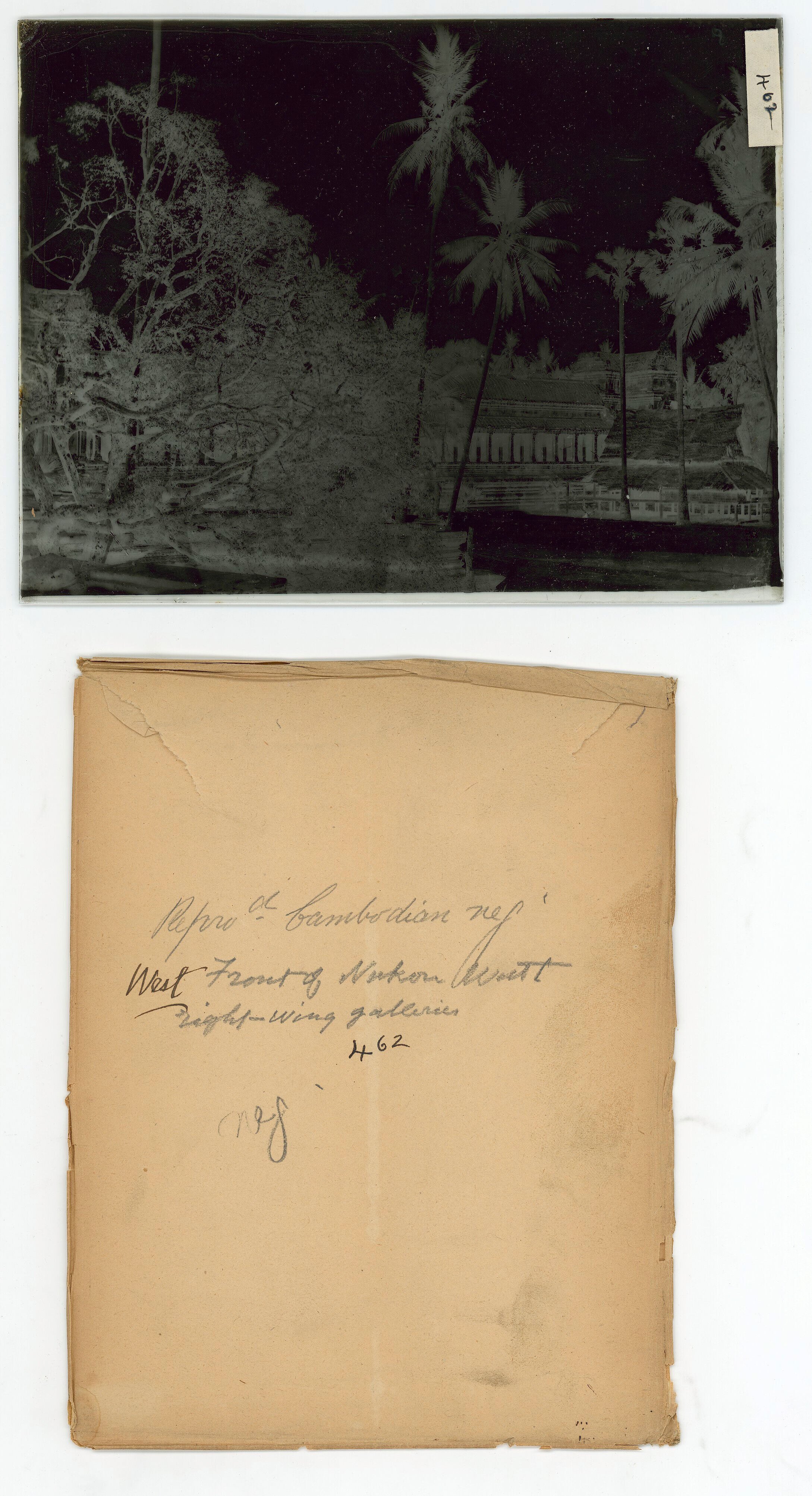

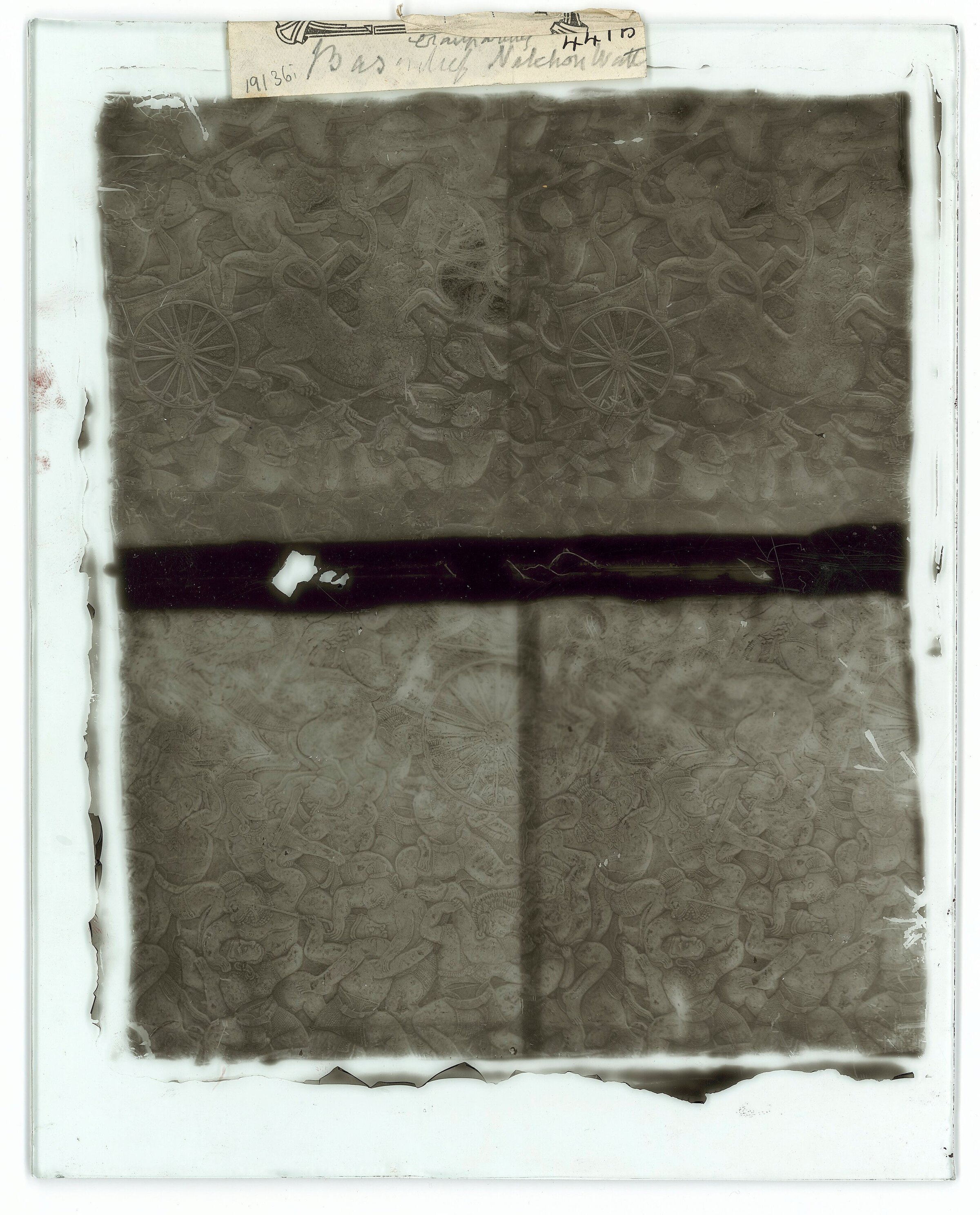

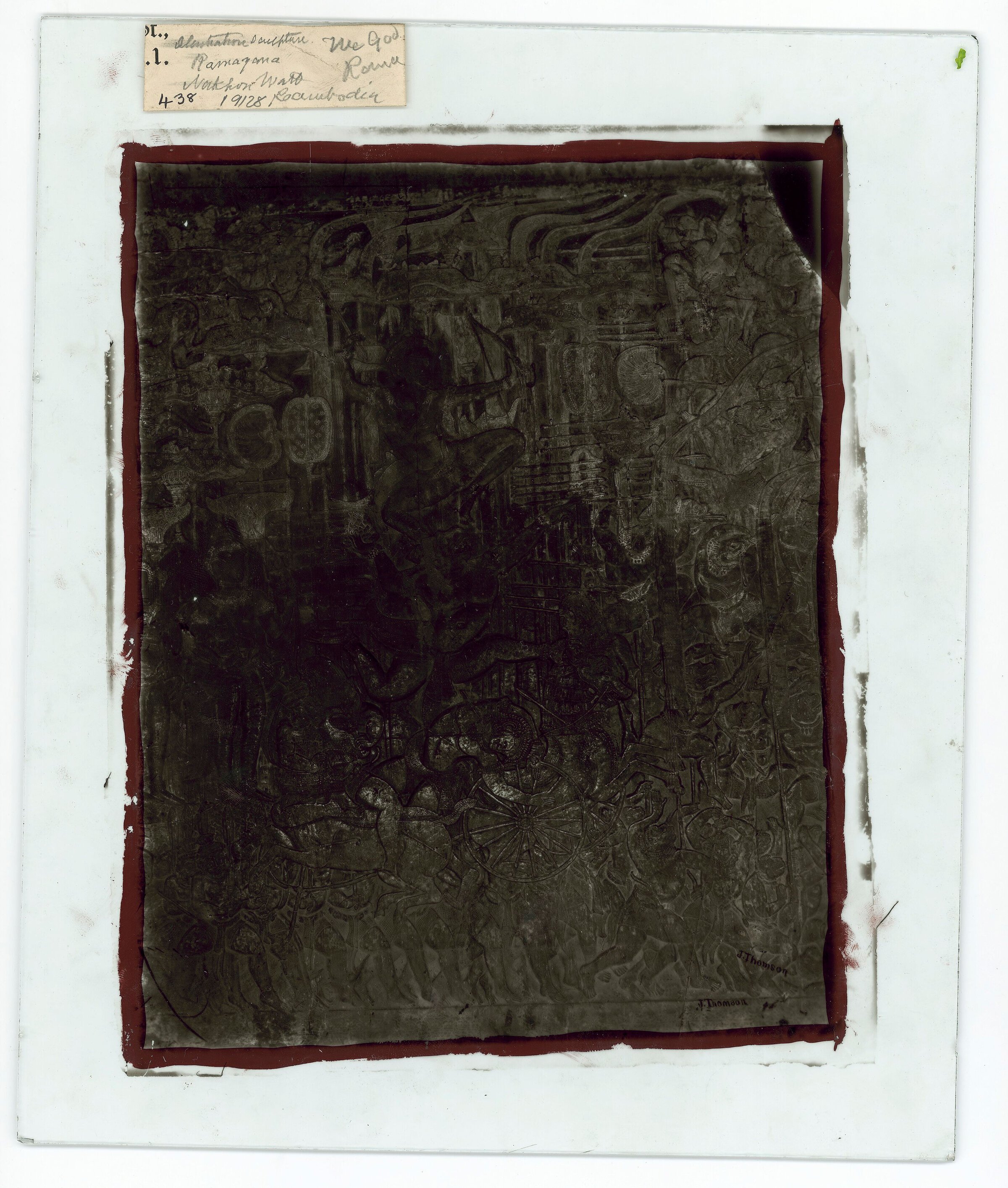

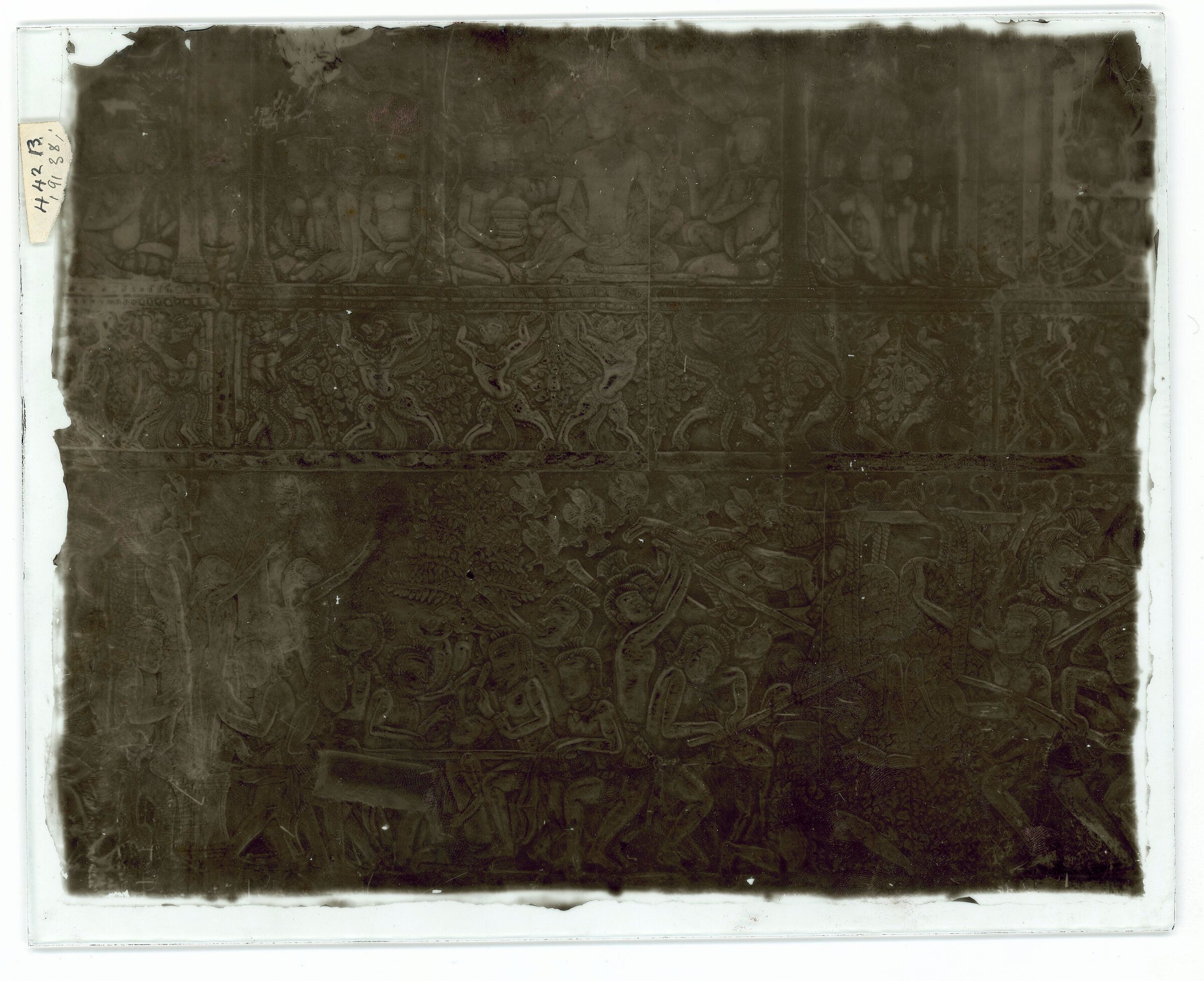

- the glass photonegative wet collodion plates (PL in captions = PLN, negative, PLG, positive);

- the first negatives made by the photographer himself, or their reproductions — labeled “repro” (N in captions);

- the photographs made in 1981 by the Wellcome Library (PH in captions). Note that colorization attempts are not really convincing;

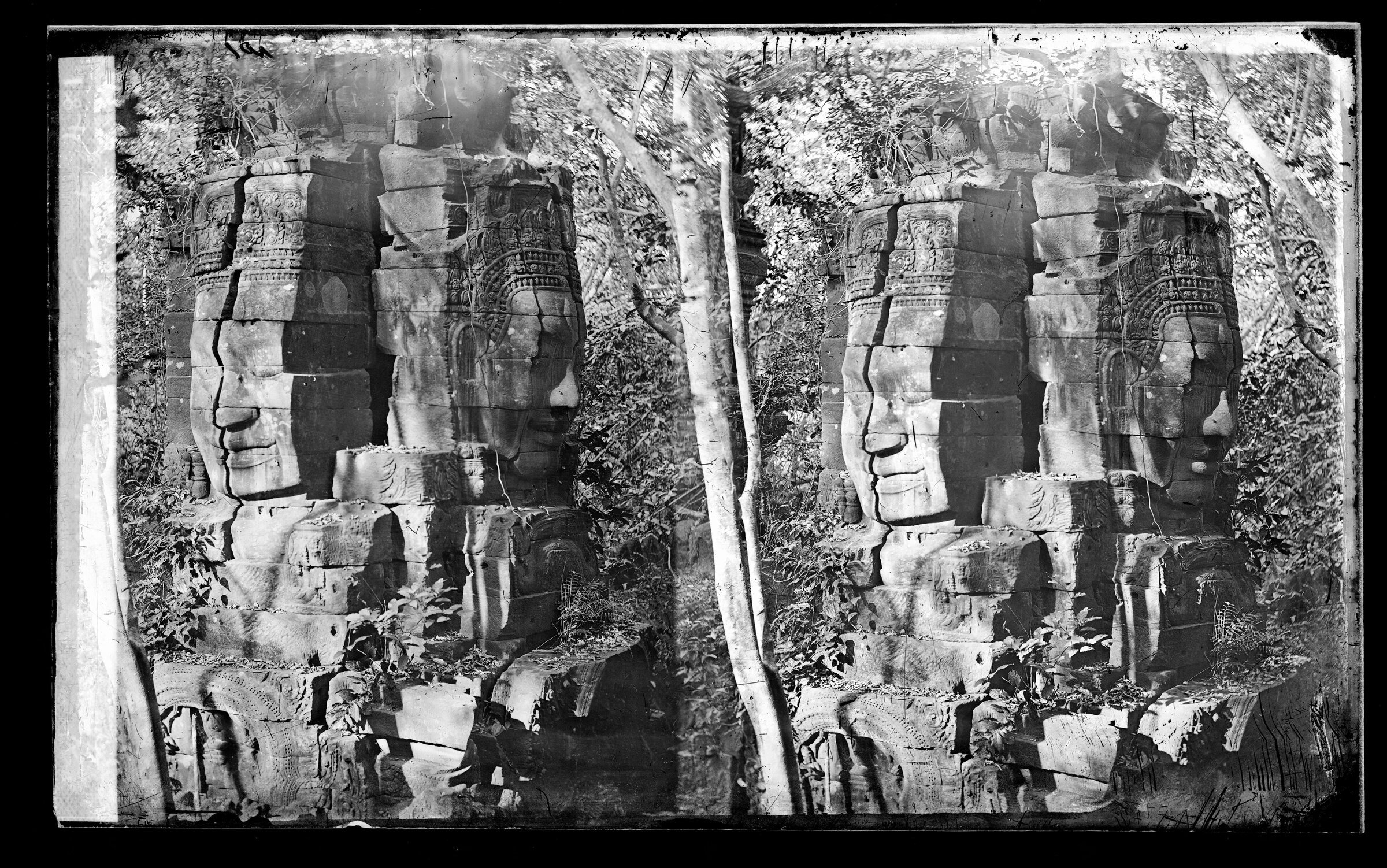

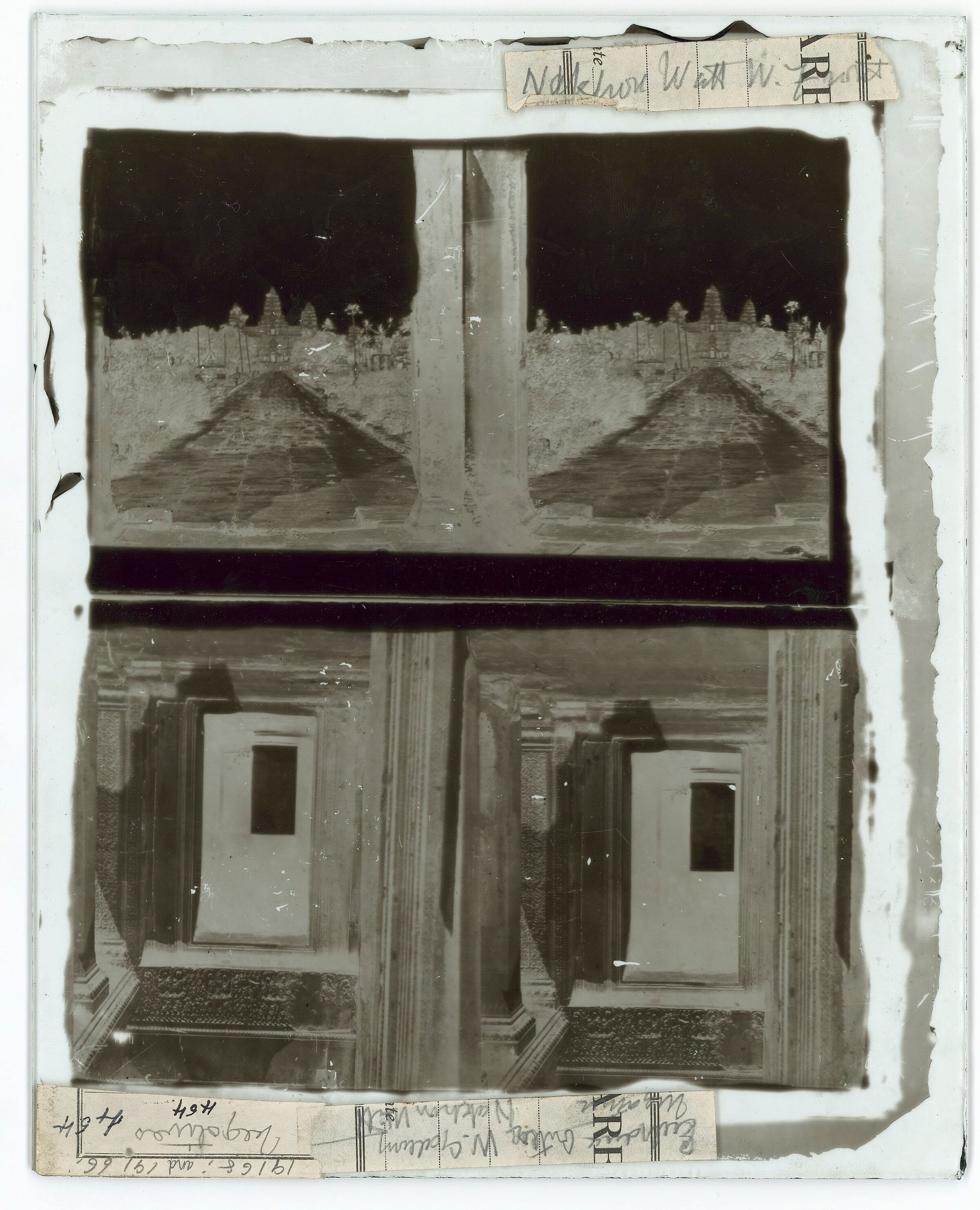

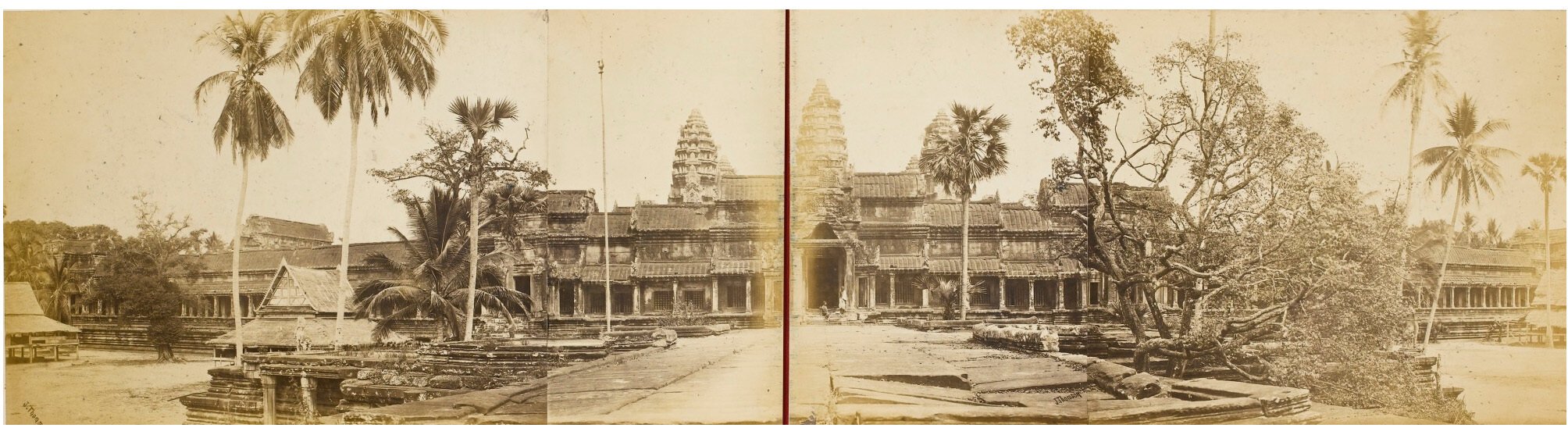

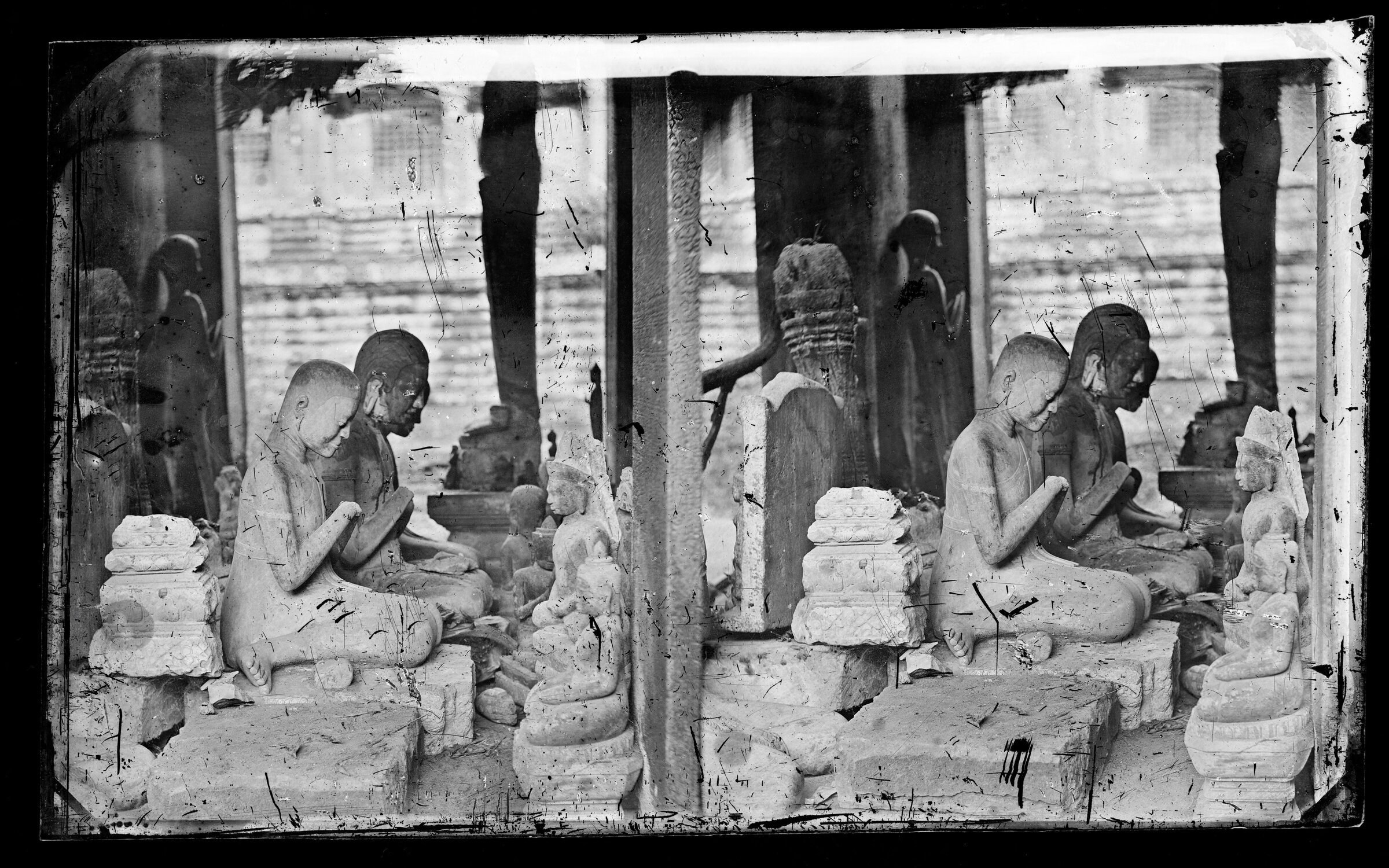

- some attempts at stereograph photos [1], as in the first image, TH1S, which is in fact a triptych. (S in captions);

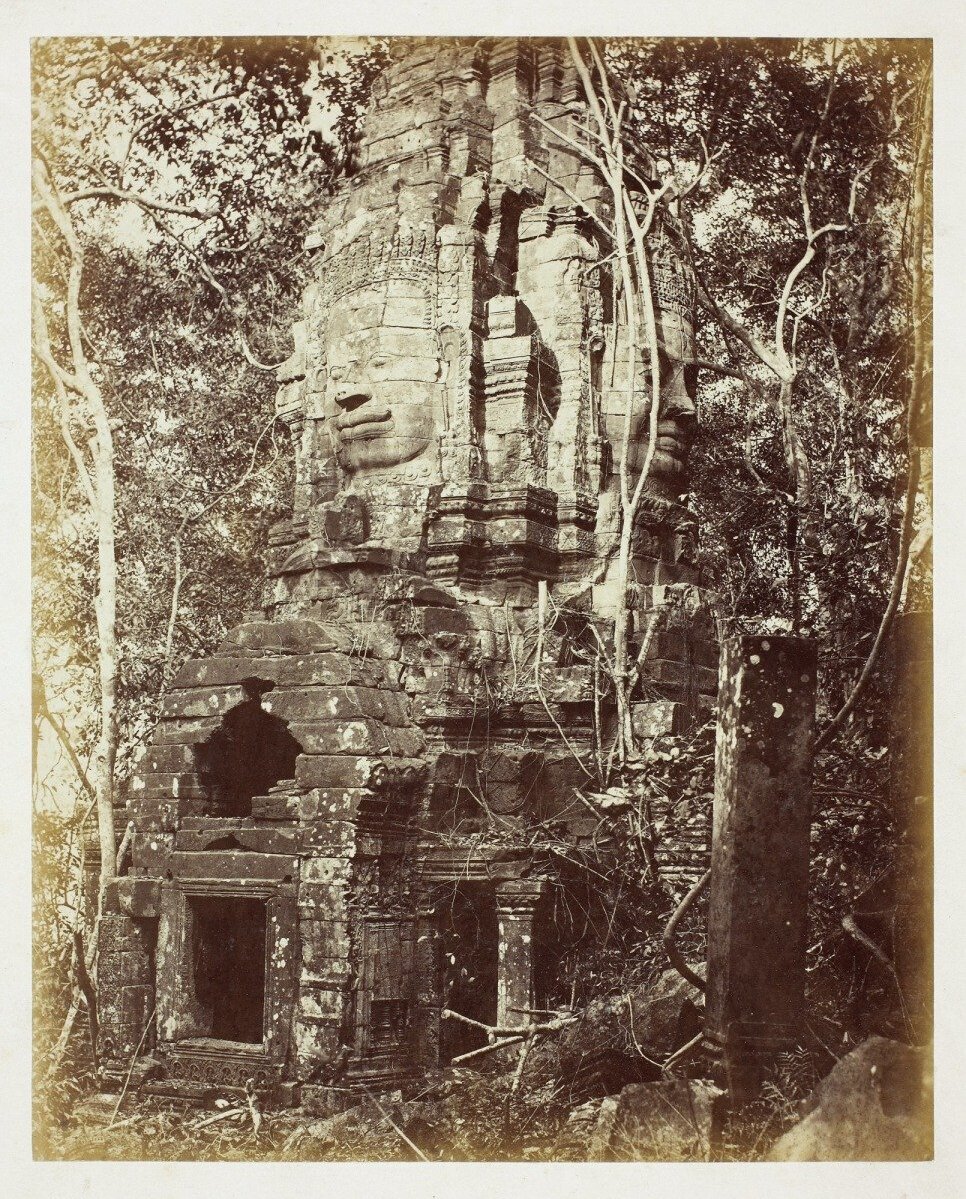

- As early as 1867, John Thomson experimented with albumen silver print technique. Some of his photographs printed in that format are living at the National Gallery of Canada (NGC), Ontario [2]. (ASP in captions);

- some of Louis Porter’s facsimile albumen prints [FAP in captions] made in 2019. See below.

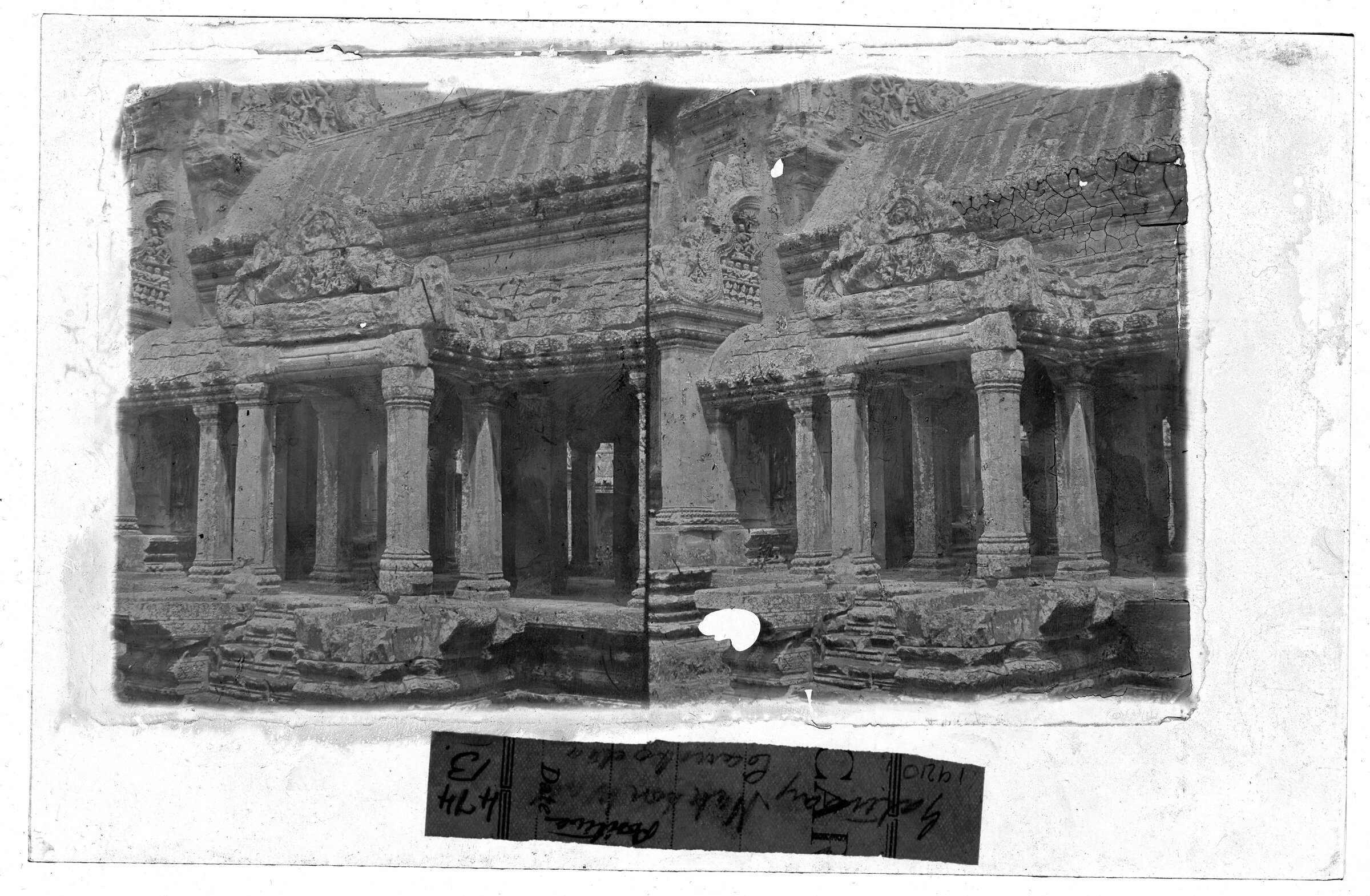

- photos published in The Antiquities of Cambodia (as early as 1867, it was Thomson’s first published book) are labeled [AC]. [There were only 16 photographs published and commented in the 79-page book]

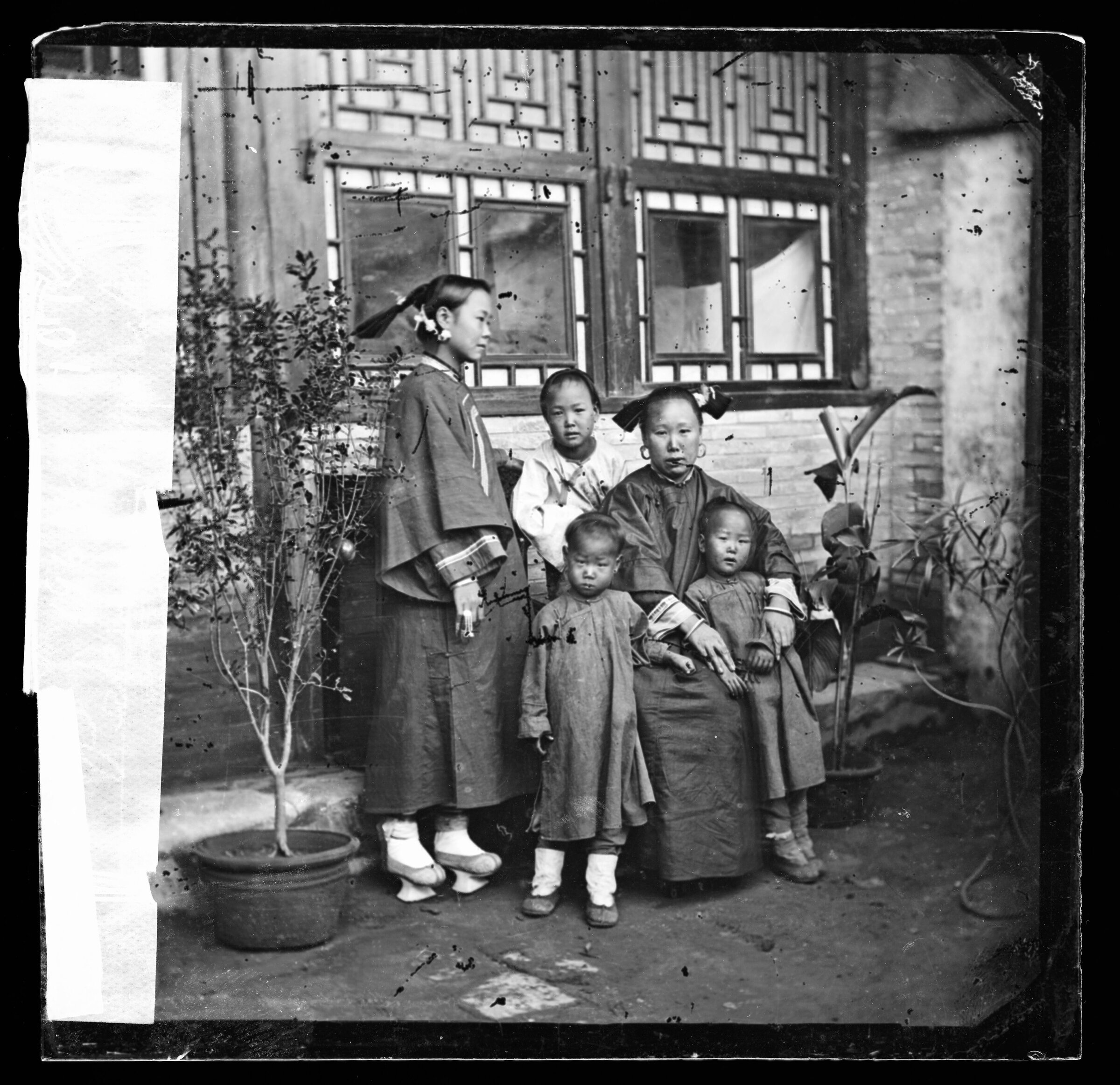

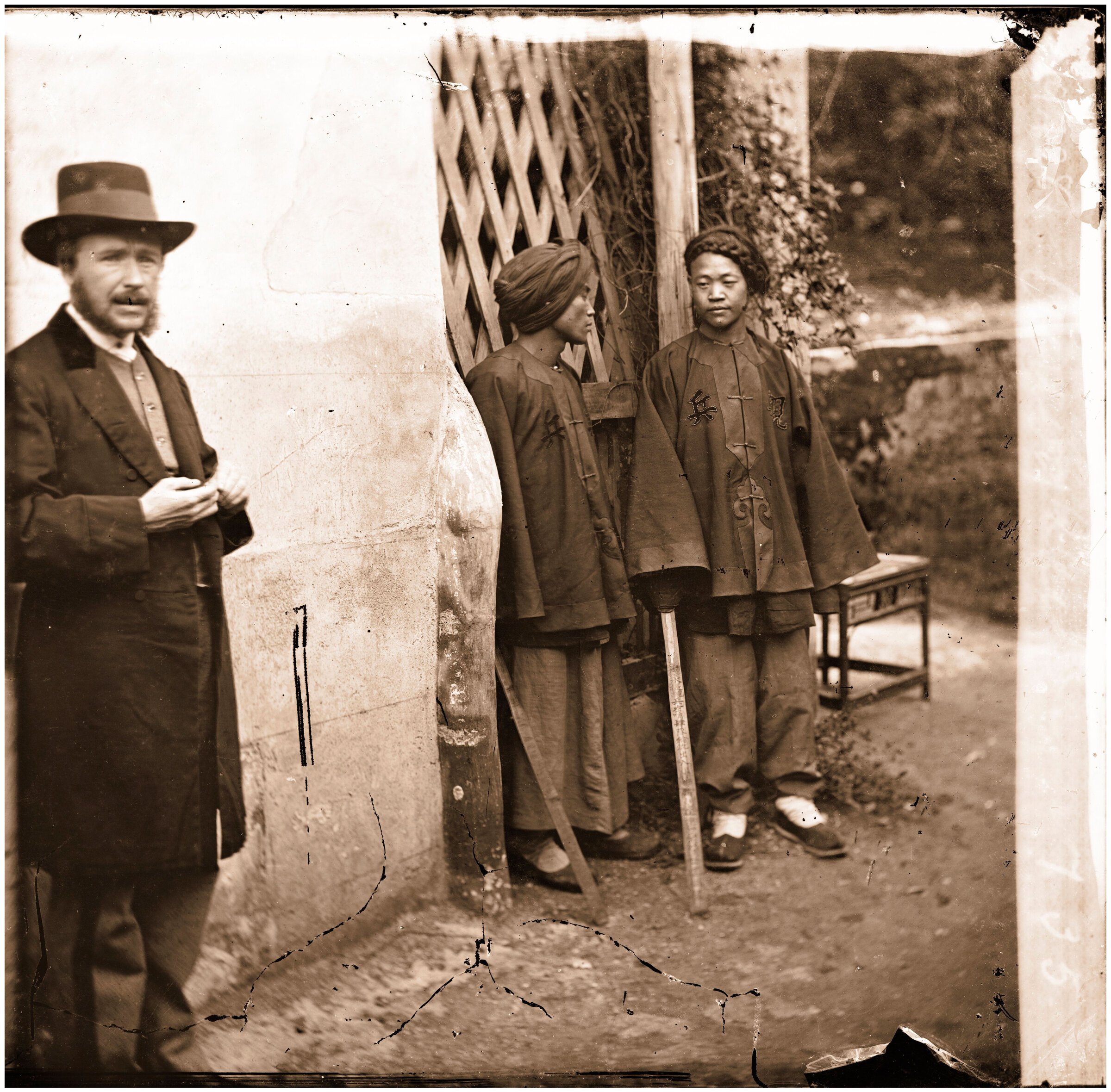

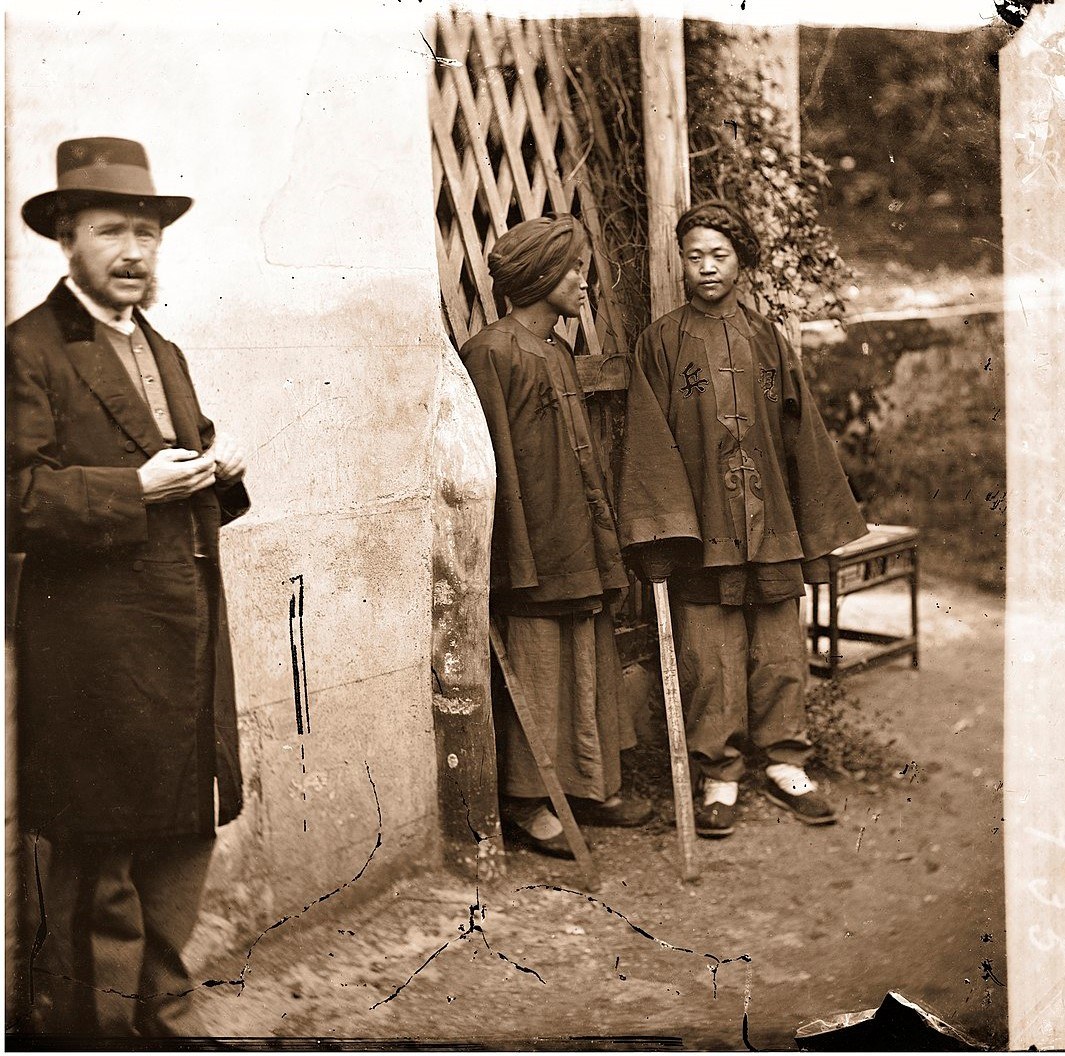

- at the end of this gallery dedicated to Angkor, we have added a) Thomson’s portrait of King Norodom b) one sample of Thomson’s work in Siam, c) three of his work in China, d) the rare photograph in which Thomson can be seen, taken in Fukien in 1871, e) an image of the chest in which he carried his glass plates.

- note that some celebrated images by John Thomson, such as Elephants outside Nakhon Wat, are not in the Wellcome collection.

The Photography

The recognition of John Thomson’s contribution to the ‘rediscovery’ of Angkor by the Western world has often been affected by the quite sterile discussion on “who was the first”? A few months after Thomson, Emile Gsell also photo documented the Khmer temples, yet he was not a seasoned professional photographer as Thomson was, and he worked chiefly in Angkor Wat. Thomson surprisingly photographed few people in Cambodia — apart from his famous portrait of King Norodom I –, while he has left us many group or individual portraits of men and women of China or Annam, and on that regard Gsell’s contribution is more exhaustive. But as for monument and architecture photography, Thomson’s work at Angkor remains a reference.

Emile Gsell’s less comprehensive work on Angkor Wat was also used for French colonial propaganda purposes: no less than 15 out of 21 images of Cambodia that were selected for the luxuriously bound album of photographs presented to Empress Eugénie in 1867 by Admiral Rigault de Genouilly — who had conquered Saigon in 1859 –, entitled Cochinchine et Cambodge, were Gsell’s views of Angkor. That was never the case with Thomson’s photographs, if only because the British Empire was at the time realizing that the French hold on Cambodia would only get stronger.

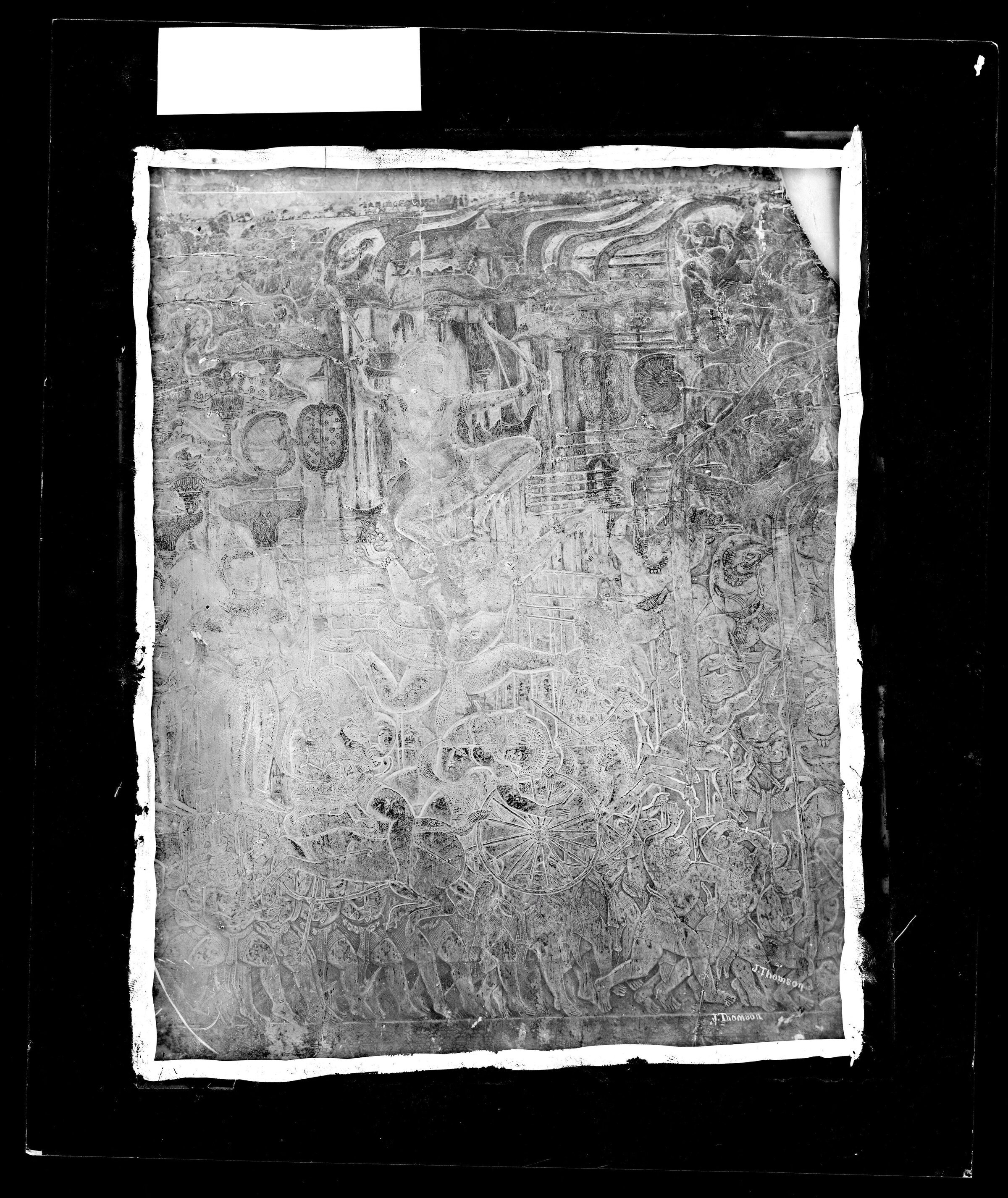

An attentive reader of Henri Mouhot’s account, Thomson took great care in taking pictures of architectural details, and of the reliefs. About the latter — grouped as TH13 series in our gallery –, he was to remark in The Antiquities...:

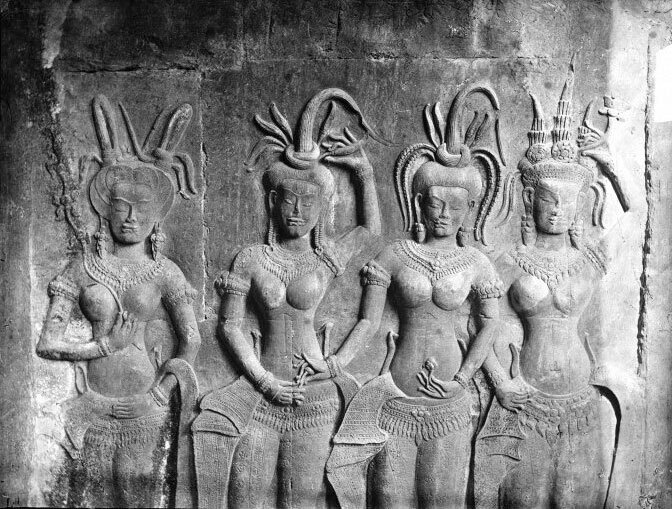

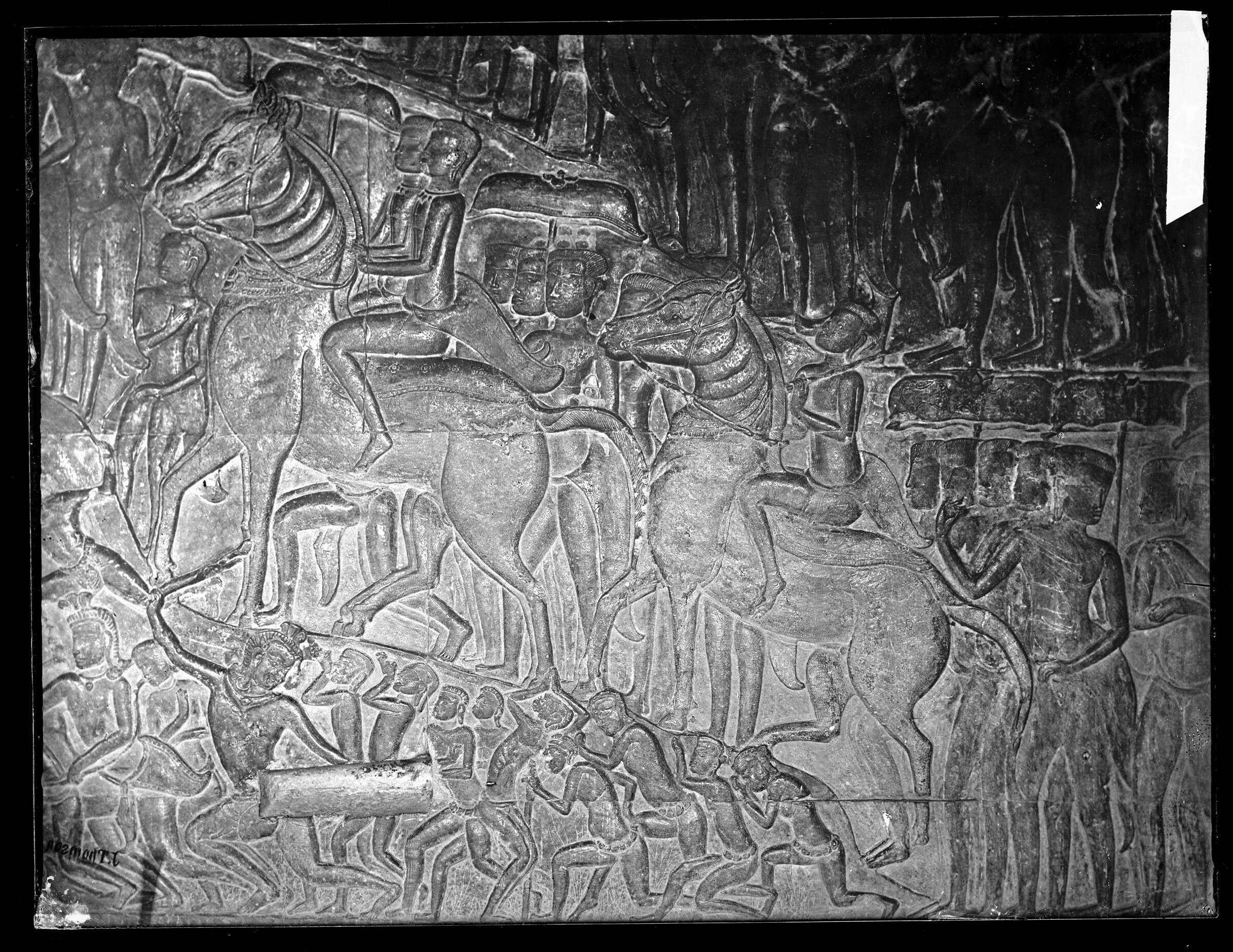

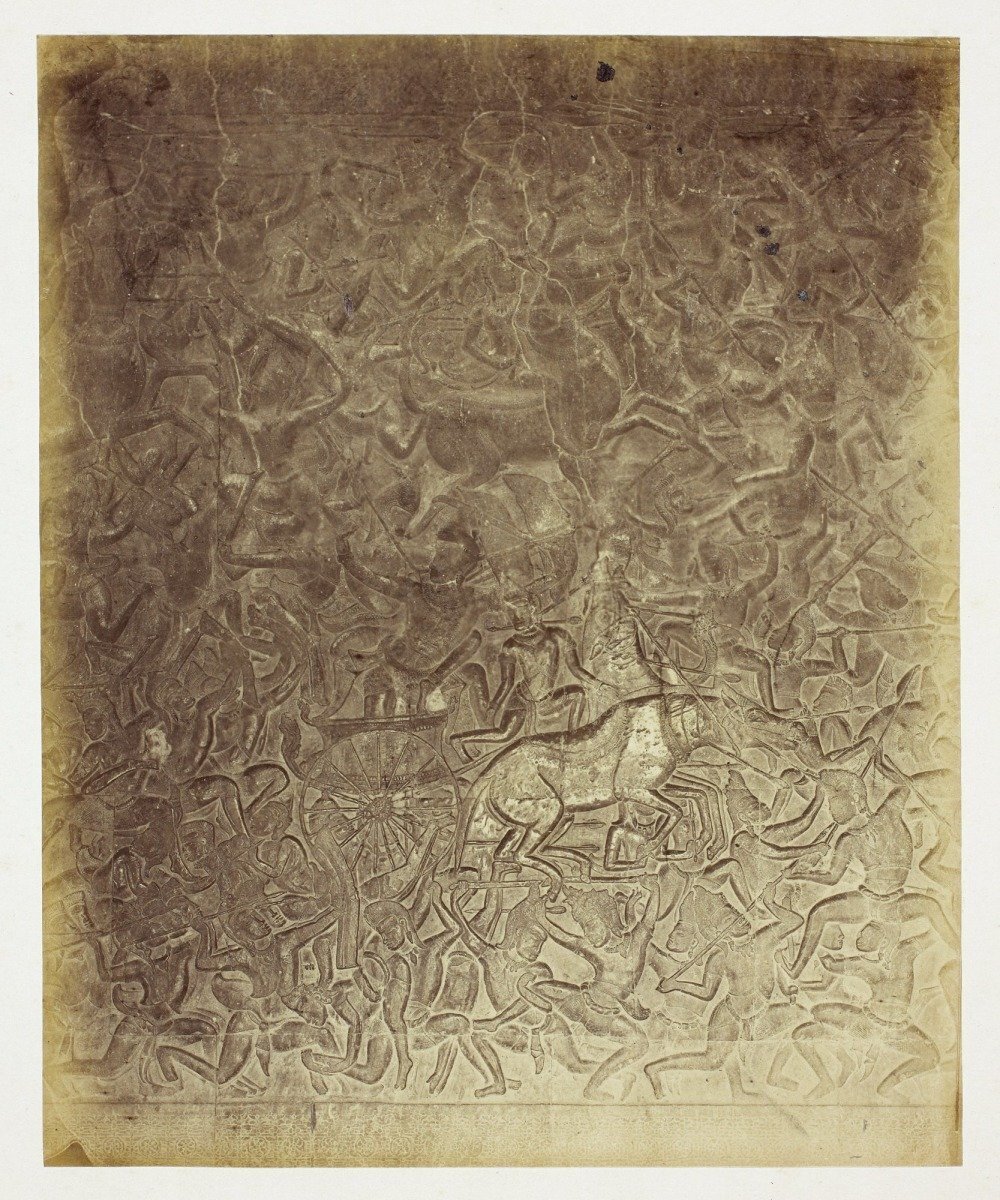

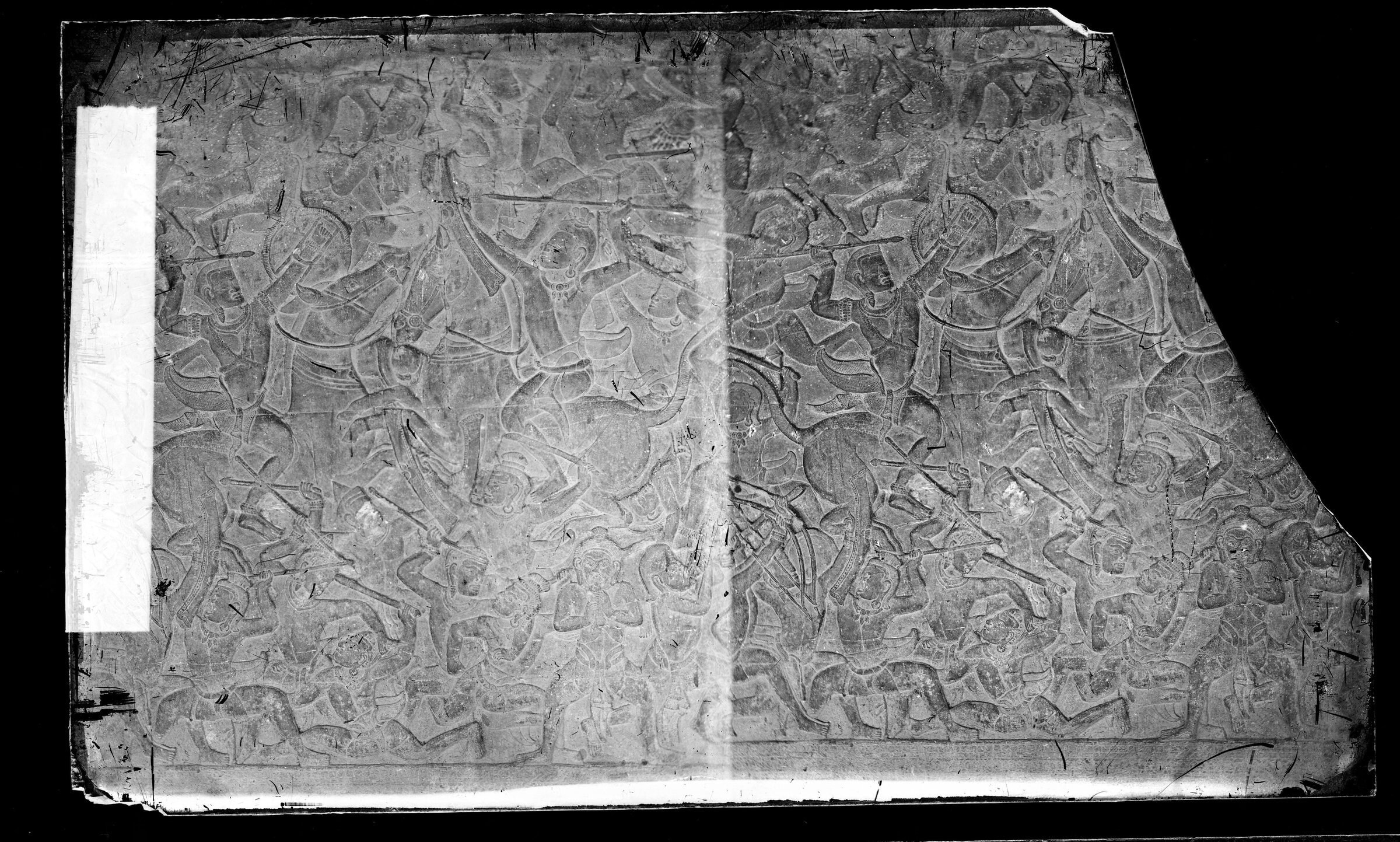

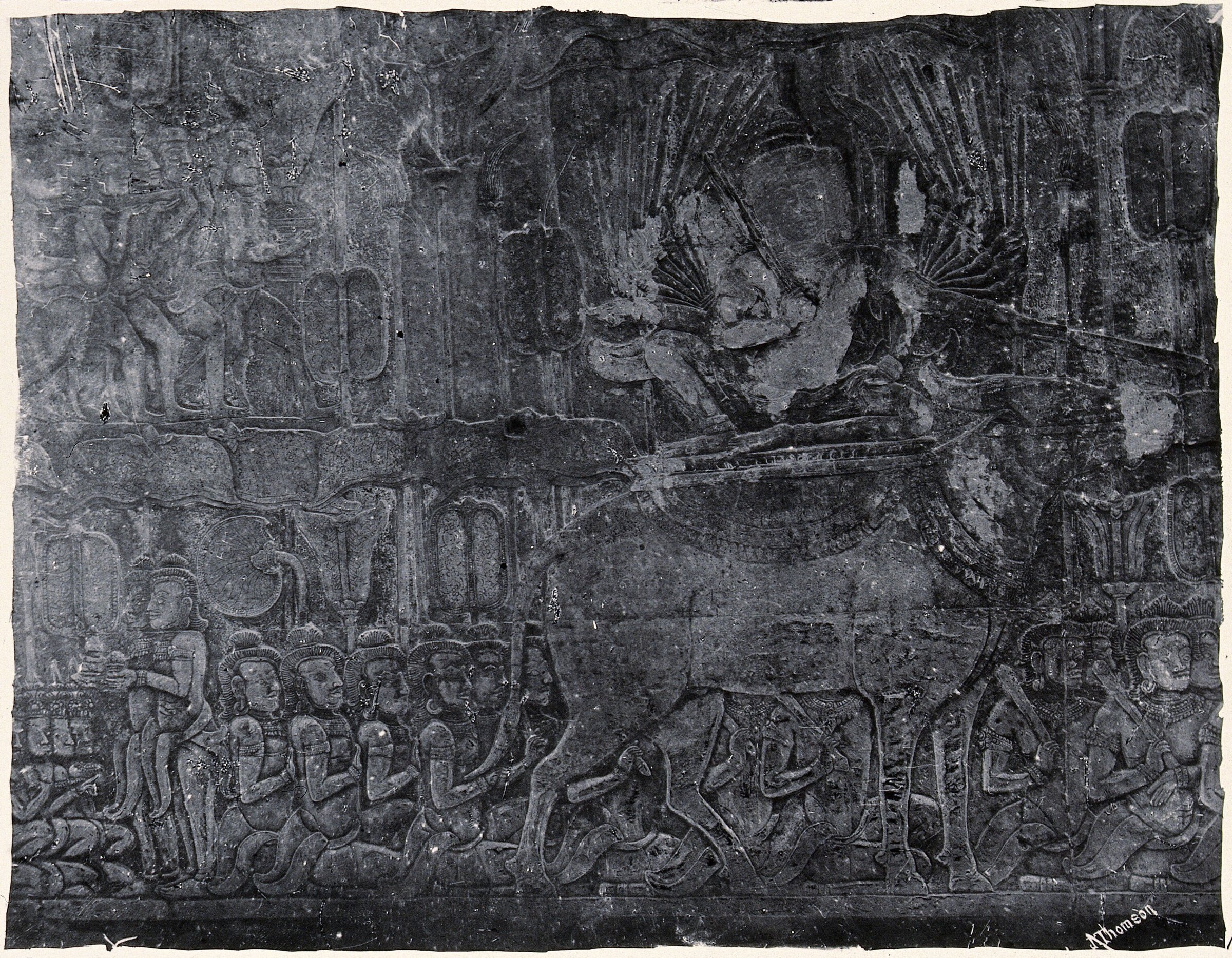

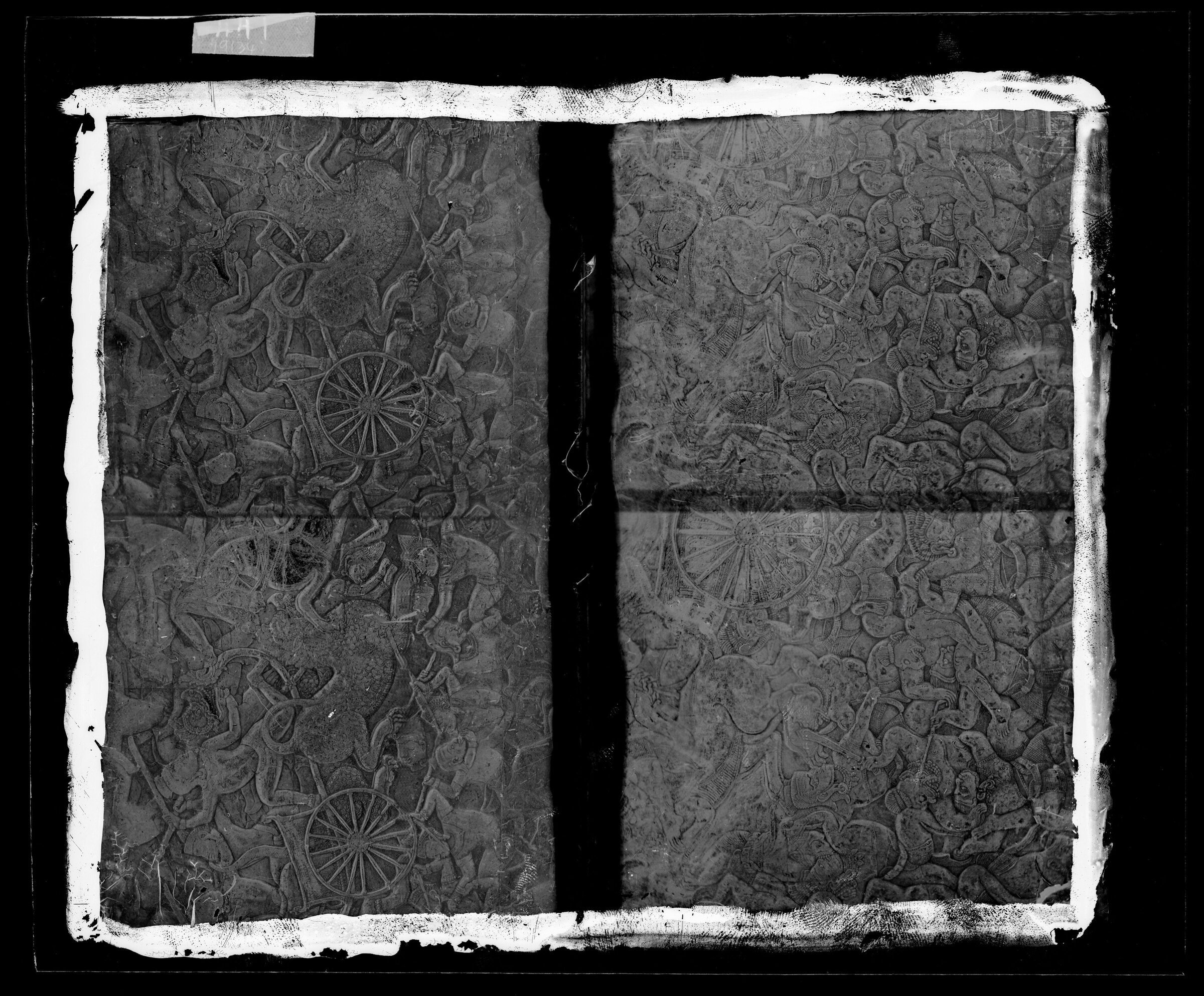

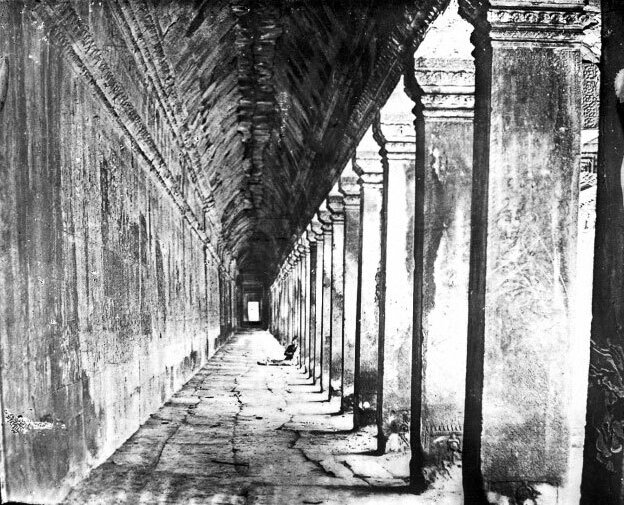

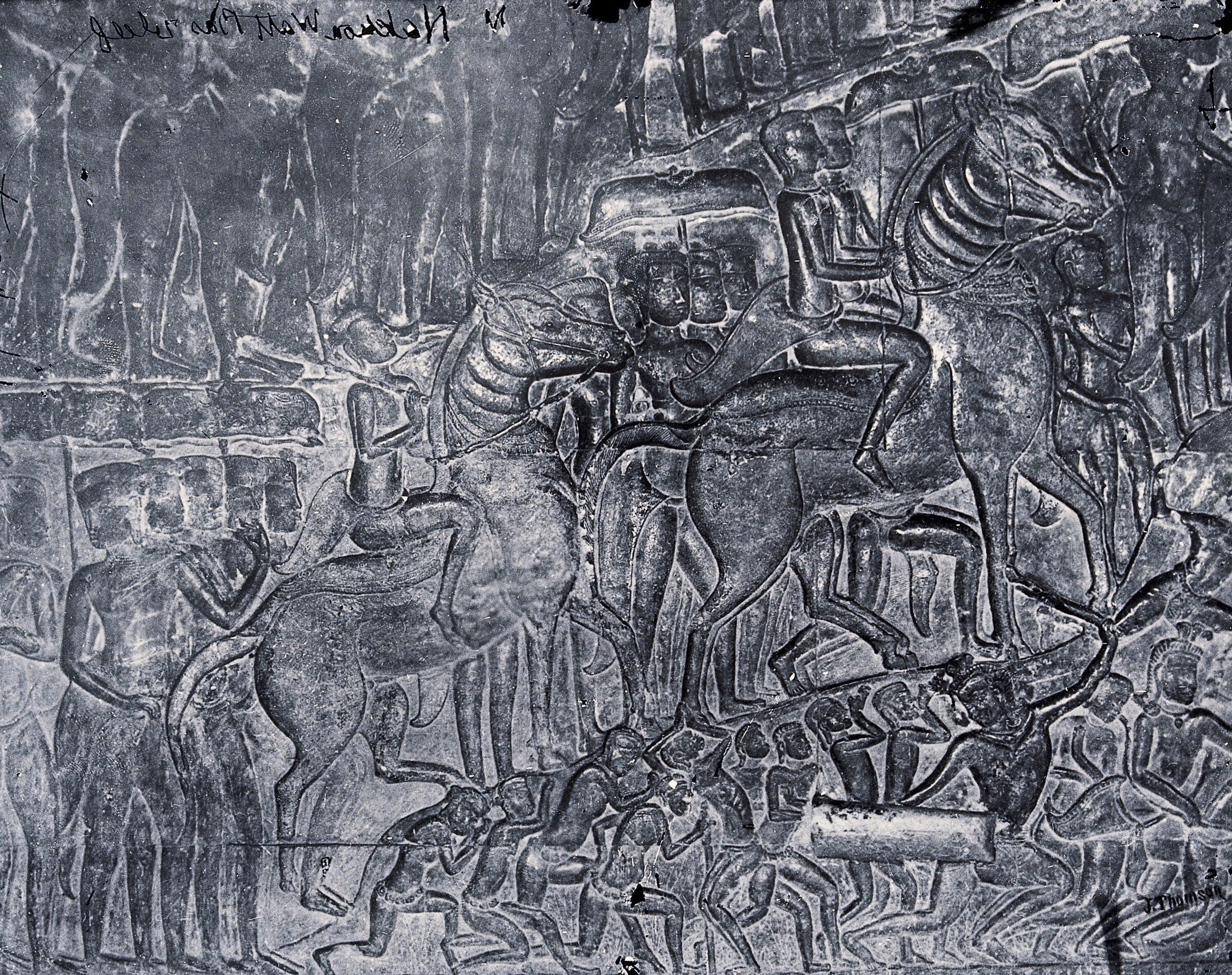

The chief representations in the Nakhon Wat galleries consist of battle scenes taken from the epic poem of Ramayana or Mahabharata (which the Siamese are said to have received from India about the 4th or 5th century). Disciplined forces are depicted marching to the field, possessing distinct characteristics, that arc soon lost in the confusion of battle. In the eager faces and attitudes of the warriorsas they press forward past bands of musicians, we see that music then, as now, had its spirit-stirring influence. We also find humane actions represented — a group bending over a wounded comrade, to extract an arrow or remove him from the field. There, also, are the most animated representations of deeds of daring and bravery — soldiers saving the lives of their chiefs; chiefs bending over their plunging steeds, and measuring their prowess in single combat and, nnally, the victorious army quitting the field laden with spoil, and guarding the numerous captives with cavalry in advance and rear. Perhaps thé most wonderful subject of all the bas-reliefs is what the Siamese call the battle of Ramakean.[…] One of the most wonderful features of the buildings are the sculptured bas-reliefs. They are found in the eight compartments formed by the outer gallery, one on each side of the central group of entrances, each subject measuring from 200 to 300 feet in length, with a height of 6 1⁄2 feet. Their aggregate length is over 2000 feet, and the number of men, animais, and mythological figures represented extends to from 16,000 to 20,000.

We could not possibly expect Thomson to write down in which Angkor Wat gallery this or that scene of the Mahabaratha or the Ramayana was photographed. His description of bas-reliefs — or simply “reliefs”, as the Angkor Wat ones are 2‑meter high! — is thematic (“battle scene”, “triumphant procession”…), and it was only decades after his visit that the whole picture of Angkor Wat sculpted walls started to come alive for Western researchers. Observe that his photographs have almost always the right exposure time, even in these dark galleries. Countless photographers have struggled with the right lighting, and with a way to render the formidable scope of these 500-meter long sculpted frescoes, culminating with Jaroslav Poncar’s use of “slit-scan photography” (rotating lenses and sliding camera on rail) in 2006 for the book Of Gods, Kings and Men, The Reliefs of Angkor Wat.

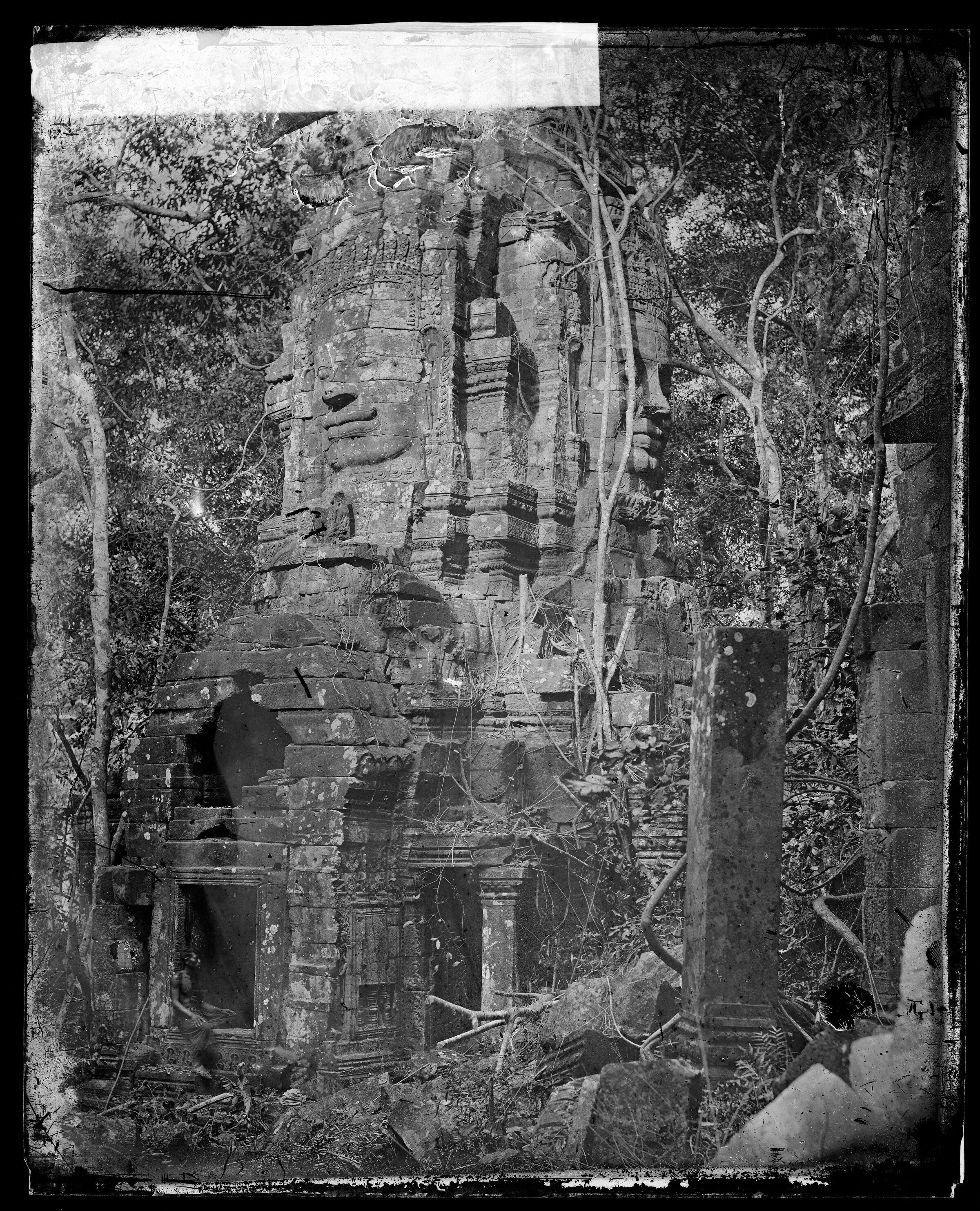

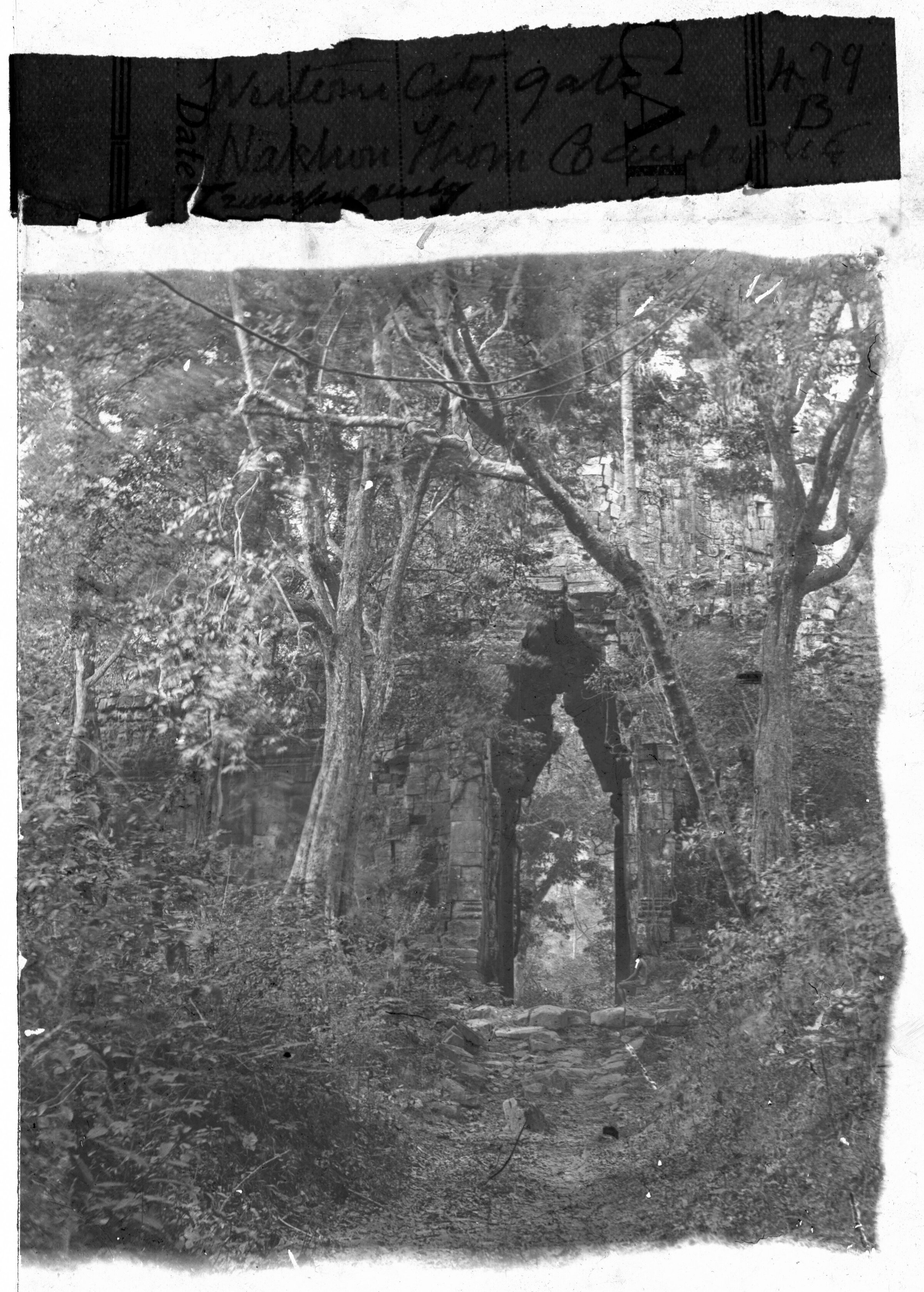

His captions are concise yet detailed — notwithstanding a few mispellings –, and his lettering always add ‘Cambodia’ after mentions of ‘Nakhon Wat’, quite a political statement since the Siamese kingdom relinquished its power on Battambang and Siem Reap provinces in 1907 only, 41 years after Thomson’s 3‑month stay. The traveler photographer also had also his quirks, like making a point in calling Angkor Thom Inthapatapuri, but he was equally perceptive. For instance, we noticed that the photograph of “one of the 51 towers of a temple at the center of Nakhon Thom” was labeled “Prea Sat Lin Poun”. This was puzzling, and we started to search the origin of that name until we founded the answer…in Thomson’s own book:

“Prea Sat Ling Poun (the place where they play hide-and seek), a modern name given by the natives on account of the labyrinth of passages and apartments that occur beneath the towers.”

This quite poetic name for Bayon was also highly accurate, as in effect លេងបិទពួន leng phuon means hide-and-seek in modern Khmer, a game still played by kids nowadays. In his Voyage d’exploration en Indochine (1885), Francis Garnier noted

Le nom khmer de ce singulier édifice est : Baion; les Cambodgiens l’appellent aussi, en raison du labyrinthe de galeries qu’il présente : Preasat ling poun, « Pagode où l’on joue à cache-cache. » Faut-il reconnaître dans ce monument l’Ile aux Cent Tours, dont parlent les historiens de la dynastie des Ming, où l’on réunissait des singes, des paons, des éléphants blancs, des rhinocéros, auxquels on servait à manger dans des auges et des vases d’or? Peut-être; et cette destination, dans les idées bouddhiques, né contredirait en rien l’affectation et le caractère

essentiellement religieux de ce singulier édifice. [The Khmer name for this singular building is: Baion; the Cambodians also call it, because of the labyrinth of galleries that it presents: Preasat ling poun, “Pagoda where one plays hide-and-seek.” Should we recognize in this monument the Island of a Hundred Towers, of which the historians of the Ming dynasty speak, where monkeys, peacocks, white elephants, rhinoceroses were gathered, to whom food was served in troughs and golden vases? Perhaps; and this destination, in Buddhist ideas, would in no way contradict the affectation and the essentially religious character of this singular building.] [p 70]

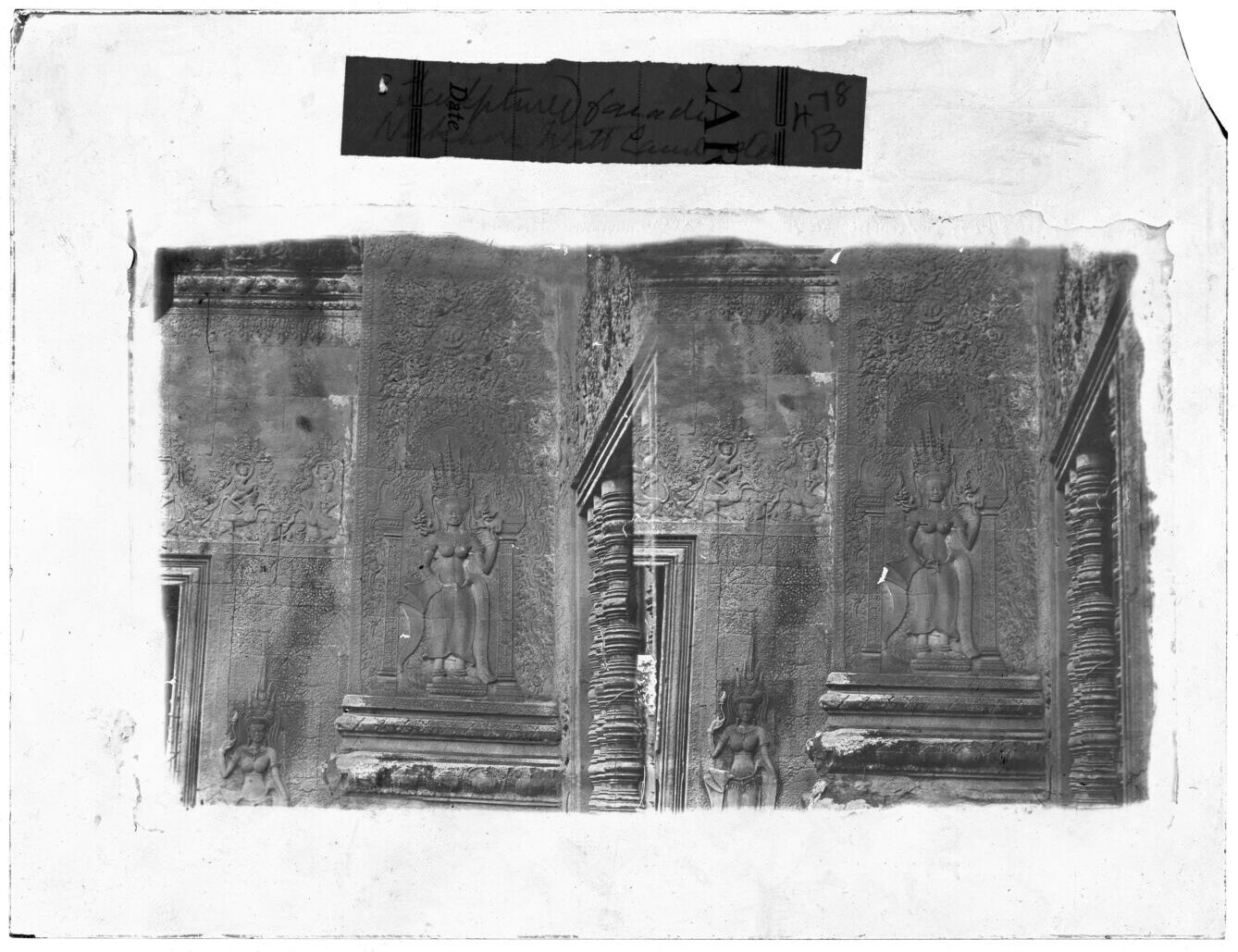

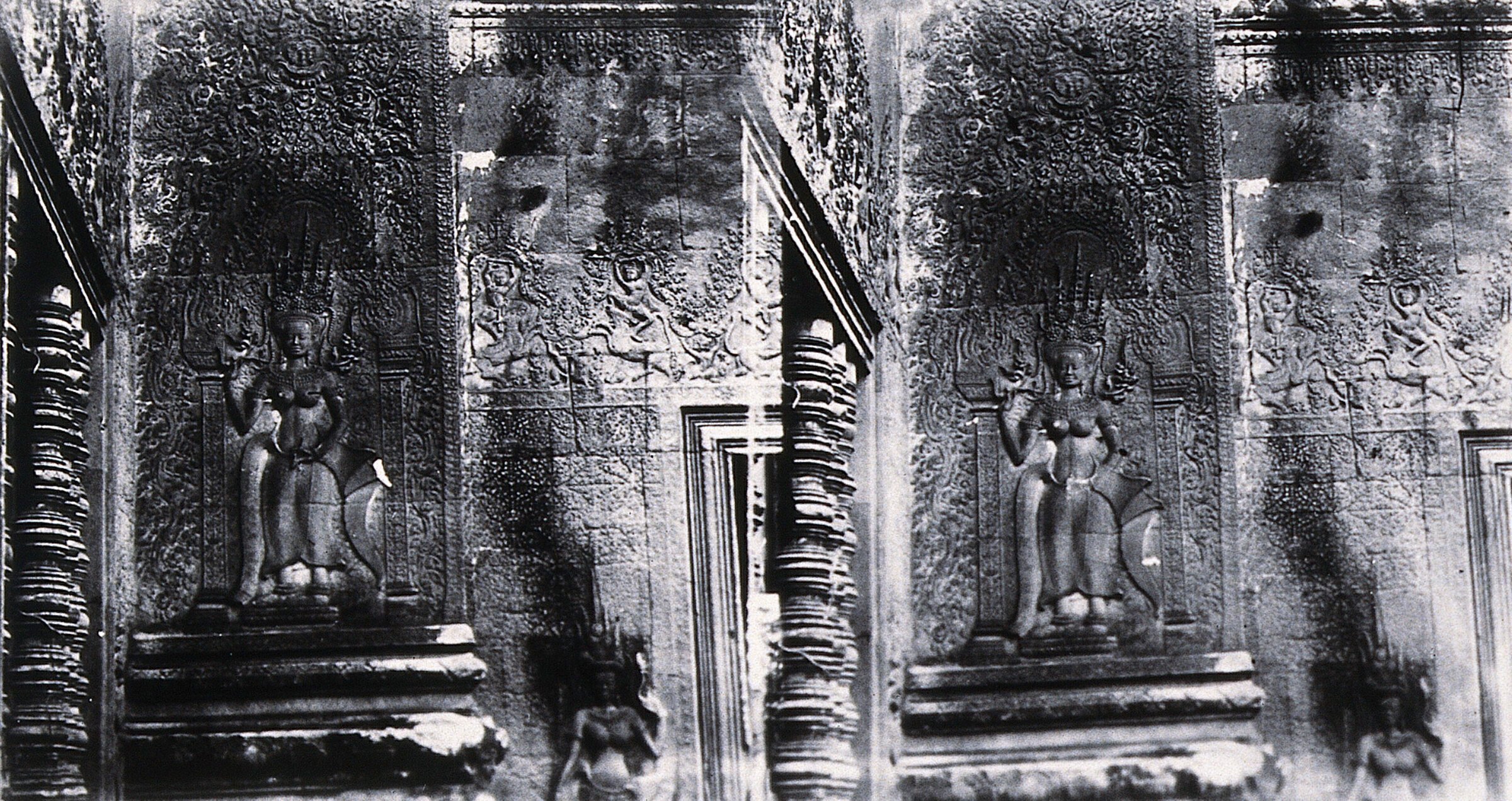

As for the devatas on pillars and walls, Thomson noted: “The female figures are known to the natives as the Chao Savan [probably a Thai phrase for “heavenly princesses”], who are supposed to form the retinue of the deified kings, or Tewadahs.”

When needed, we have added details in [ ], after identifying the photographs of monuments or reliefs briefly lettered by Thomson. Example: TH13L, M, N : “Nakhon Wat, bas-reliefs in galleries”, 1866, pl. 460 is what Thomson, to which we added: [AC: “bas-reliefs of battle scene”] [Battle of Kurukshetra, Kaurava warriors figthing the Pandavas, left center (real orientation is left-to-right. West gallery, South wing].

John Thomson’s Legacy

- The collection of original glass photonegatives made by John Thomson includes negatives made between 1868 and 1872, all purchased from Thomson by Sir Henry Wellcome in 1921. As of May 2024, we have identified there 2,399 digitized photographs, negatives, stereographs or glass plates attributed to John Thomson (about 80% of them taken in China, Formosa (Taiwan), Siam, Turkey, Greece, and the streets of London). Read more about John Thomson at Wellcome.

- In 2019, London-based artist, photographer and researcher Louis Porter developed a simple method for producing facsimile albumen prints [FAP in our labels] of Thomson’s work, using the digitised images of his glass plate negatives produced by the Wellcome Library’s imaging department. On his website, Porter explained:

The aim was to produce-process accurate facsimiles of the iconic triptych of the western façade of Angkor Wat temple, as featured in Thomson’s 1867 “The Antiquities of Cambodia”. To facilitate this, the Wellcome transferred the RAW scans of the negatives and the original Kodak IQ Smart3 Scanner to my laboratory at the college. Using contemporaneous books and articles by Thomson and with the help of modern spectral-analytical equipment I produced a series of glass collodion test charts using the same materials and methods as Thomson. These then informed the process of creating acetate inkjet negatives which could be used to make albumen prints. These prints were then gold toned, mounted and presented in a handmade portfolio folder. Papers explaining the methodologies and historical context of the work have been presnted to the Association for Historical and Fine Art Photography (AHFAP) and the Institute for Conservation (ICON).

- Photographer Jo Farrell, based in Siem Reap since 2023, is currently working on imaging Angkor Thom’s Western Gate, the one that particularly captivated John Thomson, and on a research paper. “I am fascinated by how we look at historical images and recreate the moment,” she says. [with our thanks for pointing out to us Louis Porter’s contribution.]

- We’re currently seeking a copy of Robert Philpotts’ book (Wellcome Grant): Edinburgh to Angkor: John Thomson and ‘The Antiquities of Cambodia’, Blackwater Press, London, 2017, ISBN 978 – 0946623082.

[1] Similar to card photographs, “stereograph” is a format, not a technical process. Before 1852, daguerreotypes and ambrotypes were used to create stereographs, replaced with glass stereographs in which two images are placed side by side. According to Oregon University Library website, “these were most commonly produced with cameras that had two lenses side by side, 2.5 inches apart, so that two exposures were made simultaneously.”

[2] The notice for John Thomson on NGC website reads as follows:

John Thomson was running a portrait studio in Singapore and feeling rather bored with photographing other European residents when he resolved to embark on a dangerous expedition to the interior of Cambodia. With an entourage of some twelve assistants, guides, and boatmen, he reached the ancient temple-palace of Angkor Wat, and spent several days photographing and mapping the ruins and the former Cambodian capital, Inthapatapuri. His published album includes views of the temple gateway’s western façade, details of portal carvings, and bas-reliefs depicting battles, triumphant processions, and other scenes from the epic poem “Ramayana”.

Tags: photography, Scottish explorers, 1860s, 1870s, rediscovery, Bayon, Angkor Wat, Angkor Thom, Siam, Angkor before 1907, King Norodom I, colonialism

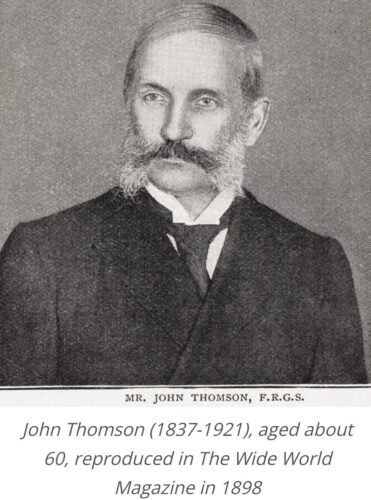

About the Photographer

John Thomson

Scottish photographer and geographer John Thomson (14 June 1837, Edinburgh – 29 Sept. 1921, Edinburgh) was a pioneer in photographying the ruins of Angkor in 1866, part of his ten-year long travel stint across Asia after joining his elder brother William in Singapore in 1862.

When he left for the Far East, he had studied photography processing and technique as an apprentice in an optical and scientific device manufacturing company, while enrolling to evening classes at Watts Institution and School of Arts to study chemistry, philosophy and geography.

Thomson was welcomed at the Court of Siam in 1865, and then to Phnom Penh Royal Palace the following year. After Cochinchina and Indochina, he traveled around China, documenting local cultures, landscapes and artefacts of the East. He insisted to travel to Angkor, with the assistance of his friend H.G. Kennedy, a British Consulate officer fluent in Siamese, after reading Henri Mouhot’s travel accounts, first published in English even if Mouhot was a French citizen.

According to Jim Mizerski in Cambodia Captured, “On January 27, 1866, John Thomson accompanied by H. G. (Henry George) Kennedy left Bangkok on his way to Angkor. His departure was noted in the Bangkok Recorder:

Mr. Thomson, the photographer who has been residing in Bangkok approximately three months, departed last Saturday, 11th day of the waxing moon in the third month, headed for Cambodia, to the ancient city of Angkor, wishing to photograph those ancient artifacts for the European people to see. Mister Thomson went by land, not by way of Chanthaburi. He expects to return in two months. During those two months anyone wishing to see the photographs taken in Bangkok may do so. The photographs are with Captain Ames, Commander of the Police, whose home is at Pom Pongpajamid. The king praised Mr. Thomson as a truly excellent photographer. I agree that none can compare to him.

In The Straits of Malacca, John Thomson recorded the start of his Cambodian adventure:

We had first intended to sail down the Gulf of Siam to Chantaboon, and thence to cross over the forest-clad mountains of that province to Battabong. But the Siamese Government declined to grant a passport for that route, which they reported as dangerous and impracticable. We were therefore reduced to the necessity of making a tedious, and, so far as health was concerned, more dangerous journey by the creeks and rivers, and across the hot plains and marshes of the south-eastern provinces of the interior.

Thomson’s original plan to follow a shortened version of Henri Mouhot’s route was not possible and his adventure in Cambodia was to be uniquely his own. There is nothing to suggest that Thomsen’s plan, at least at the time he left Bangkok, included traveling to Phnom Penh and Kampot, which he later did.

After his Asian period, he worked on the street people of London, deveoping a style of social documentary viewed as the historic basis of modern photojournalism. Yet he was at ease in all strata of society, to the point that he became portrait photographer of the Mayfair High Society, with a Royal Warrant granted to him in 1881. He had a great impact on his contemporaries, for instance introducing the famous travel writer Isabella Lucy Bird to the art of photography.

See the short online biography by the National Library of Scotland.