bracteate

fr. bractéate

Archaeological term for an ornament or plate of thinly beaten precious metal, typically a thin gold disc.

by George Coedès

George Coedès on the first comprehensive archaeological exploration in the area supposed to be the heart of the ancient Kingdom of Funan.

pdf 1.6 MB

Following the 1932 prospection of Southeast Cambodia by Robert Dalet — who, even if recognized as “correspondent” by EFEO, operated mostly by himself with Henri Parmentier’s and George Groslier’s approval -, and the 1927 – 1929 aerial photography campaigns which alerted the French community of archeologists on the existence of ancient canals in the Angkor Borei — Oc Eo area, Louis Malleret had started prospecting the area in the late 1930s, exploration he resumed in Februray 1942, despite Second World War.

This is a first summary of the archaeological finds penned by epigraphist and historian George Coedès. Published in 1947, the essay pleaded for the “Cambodian” aspect of these important discoveries, yet geopolitics were to decide otherwise only two years later, in 1949 [see the geopolitical context for the region here considered below]. Also, it was written thirteen years before Louis Malleret started the publication of his monumental L’archéologie du delta du Mékong (BEFEO, Paris, 4 vol., 1960 – 1963)

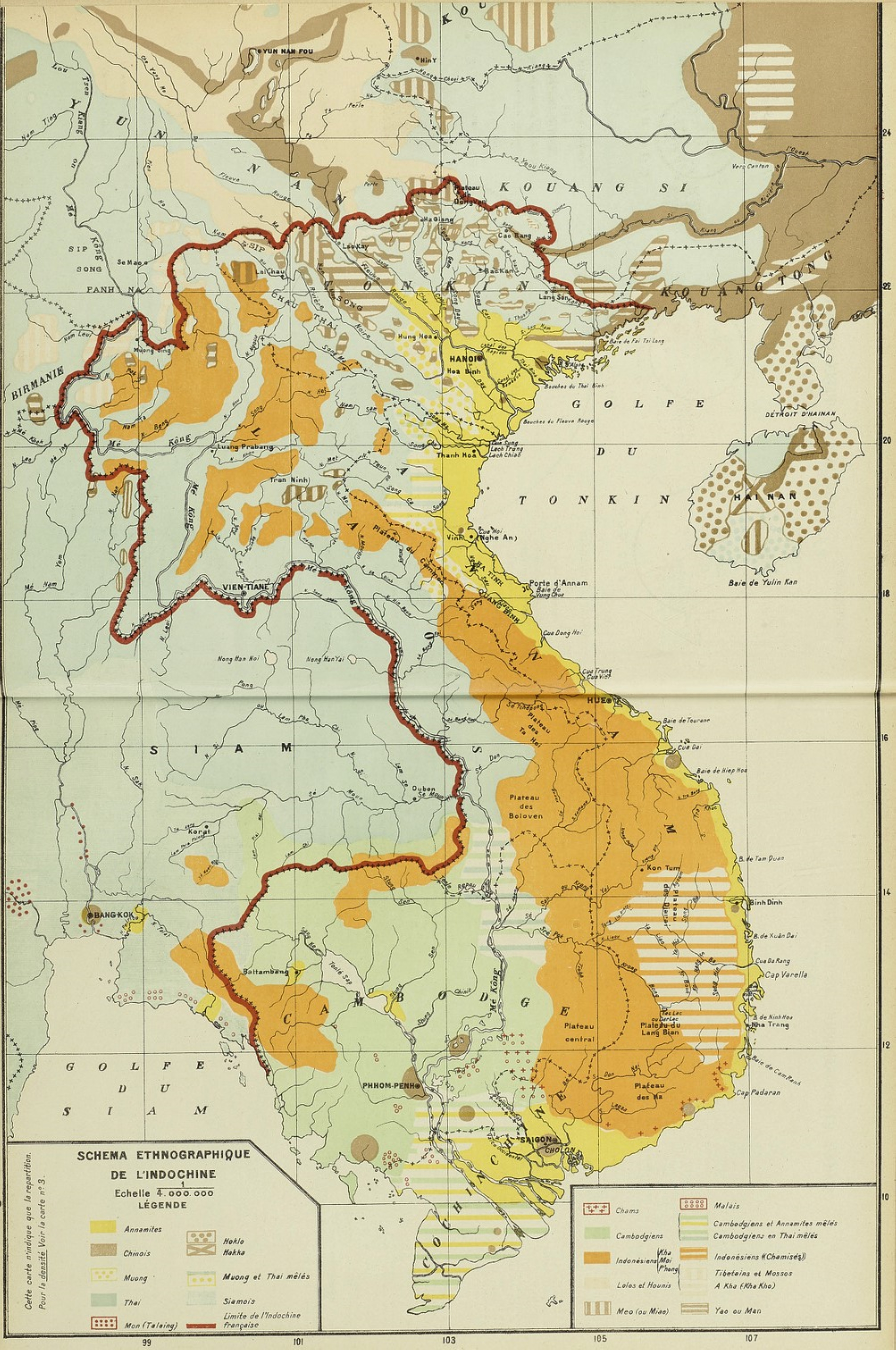

Du point de vue geologique, la Cochinchine plus meridionale de l’Indochine frangaise, est une plaine alluviale de formation recente. Du point de vue ethnique, les Annamites qui constituent 90 pc de la population n’y sont installes que depuis le XVIIIe siecle. Ces deux faits ont longtemps contribue a fausser les idees sur le r6le qu’a joue la region des bouches du Mekong dans I’histoire de la peninsule. Il y a quelques annees encore, on avait coutume de dire que la Cochinchine est une terre sans passé oui, mis a part les rares vestiges rassembles au Musee de Saigon et quelques tours khmeres dans les provinces limitrophes du Cambodge, il n’y a en somme aucune antiquite digne d’interet. Les recherches archeologiques de M. Louis Malleret, membre de I’Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient, conservateur du Musee de Saigon, ont change tout cela et sont venues rappeler a ceux qui avaient tendance a l’oublier, qu’avant d’etre peuplee tardivement par des immigrants annamites, la Cochinchine, ou vivent encore quelque 360.000 Cambodgiens, faisait partie de l’empire khmer, et meme que des vestiges prehistoriques y avaient ete reconnus des le debut de l’occupation francaise.

Les tournees effectuees par M. Louis Malleret dans les provinces de Cochinchine lui ont permis de reperer pres de 200 points archeologiques nouveaux, marques tantot par des traces de monuments, tantot par des statues anciennes conservees dans des monasteres cambodgiens ou adorees comme genies dans des pagodes annamites. Les restes des monuments sont peu spectaculaires, il faut l’avouer, mais leur ensemble commence a former sur la carte un reseau suffisamment serre pour obliger a reviser toutes les idees sur la pretendue pauvrete archeologique de la Cochinchine. Quant aux statues dont la plupart remontent a l’epoque preangkorienne, toutes sont interessantes au point de vue iconographique; quelques-unes d’une rare qualite esthetique et constituent desormais les pieces maitresses de la collection d’art khmer de la Cochinchine au Musee de Saigon. Au cours de ses recherches, M. Louis Malleret a reconnu un certain nombre d’anciennes zones d’habitat, reliees entre elles par des canaux reconnaissables sur les photographies aeriennes. Ces investigations qui se sont poursuivies pendant six ans, principalement dans les provinces de l’Ouest, permettront de dresser la carte des antiquites de la Cochinchine et d’apporter une precieuse contribution a l’histoire du Fou-nan et de l’ancien royaume khmer dont le centre, dans les premiers siecles de l’ere chretienne, se trouvait dans la basse Cochinchine et le Cambodge meridional.

[“From a geological point of view, the southernmost Cochinchina of French Indochina is an alluvial plain of recent formation. From an ethnic point of view, the Annamites who constitute 90 pc of the population have only settled there since the 18th century. These two facts have long contributed to distorting ideas about the role played by the region of the mouths of the Mekong in the history of the peninsula. A few years ago, it was customary to say that Cochinchina is a land without a past. Yes, apart from the rare remains gathered at the Saigon Museum and a few Khmer towers in the provinces bordering Cambodia, there are no overall no antiquity worthy of interest. The archaeological research of Mr. Louis Malleret, member of the French School of the Far East, curator of the Saigon Museum, changed all that and came to remind those who tended to forget that before Being populated late by Annamese immigrants, Cochinchina, where some 360,000 Cambodians still live, was part of the Khmer empire, and even prehistoric remains had been recognized there from the start of the French occupation.

The tours carried out by Mr. Louis Malleret in the provinces of Cochinchina allowed him to identify nearly 200 new archaeological points, sometimes with traces of monuments, sometimes with ancient statues preserved in Cambodian monasteries or worshiped as genies in Annamite pagodas. The remains of the monuments are not very spectacular, it must be admitted, but together they begin to form a sufficiently tight network on the map to force us to revise all ideas about the alleged archaeological poverty of Cochinchina. As for the statues, most of which date back to the pre-Angkorian era, all are interesting from an iconographic point of view; some of rare aesthetic quality and now constitute the centerpieces of the collection of Khmer art from Cochinchina at the Saigon Museum. During his research, Mr. Louis Malleret recognized a certain number of ancient habitat areas, linked together by channels recognizable in aerial photographs. These investigations, which continued for six years, mainly in the western provinces, will make it possible to map the antiquities of Cochinchina and make a valuable contribution to the history of Fou-nan and the ancient kingdom. Khmer whose center, in the first centuries of the Christian era, was in lower Cochinchina and southern Cambodia.”]

ADB Input: The original excavation report, 1944

Louis Malleret himself was to give some precious details on his 1942 – 4 prospection in his “Les fouilles d’Oc-èo (1944): Rapport préliminaire”, BEFEO 45 – 1, 1951 [via Persee for this digital version), a report belatedly published because of Second World War’s impact on the region:

Le site d’Oc-èo est situé dans la frange maritime du Delta du Mékong bordant le Golfe de Siam, et fait partie d’un ensemble de sites founanais reconnus dans le Tranbassac principalement en 1944. Il s’étend sur le village de My-lam, canton de Kiên-hào, à la limite des provinces de Long-xuyên et de Rach-gia en 10° 13′ 32“N. et 105° 9′ 17″ E (coordonnées des tertres centraux). Je l’avais parcouru pour la première fois, le 11 avril 1942 et signalé comme une succession de tertres dominant la plaine limoneuse qui s’étend du Phnom Bathé à la mer. La découverte fortuite d’un important bijou d’or y avait attiré les orpailleurs en grand nombre. Des circonstances nées de la guerre n’avaient pas permis d’y envoyer immédiatement une mission de fouilles et, tout en provoquant de la part des pouvoirs administratifs, certaines mesures de protection, je m’étais attaché à racheter aux fouilleurs clandestins, le plus grand nombre d’objets trouvés par eux. Au début de l’année 1944, M. George Coedès alors Directeur de l’Ecole [EFEO], voulut bien me confier officiellement la mission d’effectuer sur place une campagne de fouilles, avec la collaboration de M. Manikus, Chef du Service Photographique et de M. Trân-buy-Ba, dessinateur. La mission comprenait en outré, un secrétaire du Musée Blanchard de la Brosse, M. Dang-van-Minh et un mouleur de l’Ecole d’Art de Biên-hoà, M. Nguyen-van-Yên. Le concours de vingt jeunes gens servant de personnel d’encadrement fut acquis pendant le premier mois. Dix gardes civils assurèrent la police du site et de ses abords.

[“The Oc-èo site is located in the maritime fringe of the Mekong Delta bordering the Gulf of Siam, and is part of a group of Founan sites recognized in Tranbassac mainly in 1944. It extends over the village of My-lam, district of Kiên-hào, on the border of the provinces of Long-xuyên and Rach-gia at 10° 13′ 32“N. and 105° 9′ 17“E (coordinates of the central mounds). I had traveled there for the first time on 11 April 1942 and reported it as a succession of mounds dominating the silty plain which extends from Phnom Bathé to the sea. The chance discovery of an important gold jewel had attracted the gold miners there in large numbers. Circumstances arising from the war did not allow an excavation mission to be immediately sent there and, while provoking certain protective measures from the administrative powers, I endeavored to redeem from the clandestine excavators as many objects found by them as possible. At the beginning of 1944, Mr. George Coedès, then Director of the School [EFEO], was kind enough to officially entrust me with the mission of carrying out an excavation campaign on site with the collaboration of Mr. Manikus, Head of the Photographic Service and Mr. Trân-buy-Ba, designer. The mission also included a secretary from the Blanchard de la Brosse Museum, Mr. Dang-van-Minh and a molder from the Biên-hoà School of Art, Mr. Nguyen-van-Yên. The assistance of twenty young people serving as supervisory staff was acquired during the first month. Ten civil guards policedthe site and its surroundings.]

Further on, he studied the possible location of Oc-eo fifteen centuries earlier, given the geological mutation of the area:

C’est en réalité toute l’évolution du delta du Mékong qui se trouve mise en cause par la découverte du site d’Oc-èo. Cette histoire est loin d’être connue et nous avons dû pour notre compte en entreprendre l’étude à l’échelle du Transbassac, sans que l’état de nos recherches puisse nous permettre encore d’avancer une opinion décisive. Mais d’ores et déjà, il apparaît que le comportement des crues a considérablement varié et que l’hydrologie de la région a connu des modifications à mesure que le colmatage effaçait l’ancien système de canaux créé par d’anciens occupants du sol et dont le tracé atténué apparaît encore à l’observation aérienne. Il y a lieu, à un autre égard, de tenir compte de la progression du rivage qui, le long du Golfe de Siam, paraît avoir été extrêmement lente. Quels que soient les résultats de nos recherches géographiques, on peut affirmer que la ville ancienne n’était pas établie directement sur le littoral, mais qu’elle bénéficiait d’une position mi-terrestre, mi-maritime qui pouvait offrir des avantages, mais comportait aussi des dangers. L’énigme la plus troublante semble résider dans le fait qu’en dehors de ses monuments dont les dallages sont tous défoncés, la ville né paraît pas avoir été pillée au moment de sa ruine. On né peut guère s’expliquer autrement l’abondance des bijoux d’or uniformément répartis dans un terrain alluvionnaire.

[“In reality, it is the entire evolution of the Mekong delta which is called into question by the discovery of the Oc-eo site. This story is far from being known and we have had to undertake a study on the scale of the Transbassac, without the state of our research being able to yet allow us to put forward a decisive opinion. But already it appears that the behavior of floods has varied considerably and that the hydrology of the region has undergone modifications as clogging erases the ancient system of canals created by former inhabitants, of which a faded outline still appears on aerial observation. It is necessary, in another respect, to take into account the progression of the shore which, along the Gulf of Siam, appears to have been extremely slow. Whatever the results of our geographical research, we can affirm that the ancient city was not established directly on the coast, but that it benefited from a half-land, half-maritime position which could offer advantages, but also had dangers. The most disturbing enigma seems to lie in the fact that apart from its monuments whose paving stones are all smashed, the city does not appear to have been pillaged at the time of its ruin. We can hardly explain otherwise the abundance of gold jewelry uniformly distributed in alluvial soil.”]

On the archaeological finds themselves, he wrote:

Le site a livré en grande abondance des bijoux d’or, menus lingots, fils torsadés, courbés, aplatis ou tressés, indiquant un travail d’orfèvrerie. Ils se répartissent en plusieurs séries. Des grains de collier dont les proportions varient de dix millimètres à cinq dixièmes de millimètres, correspondent aux mêmes solides géométriques que les perles d’enfilage en verre ou en pierres semi-précieuses. Les bagues présentent des types très divers, depuis le simple anneau, jusqu’au modèle à chaton enrichi ou non de pierreries. Quelques-unes sont des sceaux portant des caractères sanskrits. Certaines sont ornées d’une menue figurine de boeuf à bosse accroupi. D’autres bijoux semblent être des pendentifs ou des anneaux d’oreilles, articulés ou non. Une médaille incuse du type des bractéates porte une effigie laurée avec le nom d’Antonin le Pieux et l’indication de sa quinzième puissance tribunitienne soit 152 AD. Une seconde moins lisible semble pouvoir être assignée à Marc-Aurèle. Une autre qui a conservé un anneau d’attaché montre une effigie assez fruste entourée d’un cercle de globules. D’autres objets sont des étuis, des pendeloques, des fleurs, des rosaces, des garnitures avec décor en filigrane et de destinations variées. On trouve parmi eux un clou d’or et des aiguilles à chas, ainsi que des feuilles gravées de personnages parmi lesquels on reconnaît une élégante joueuse de harpe. Beaucoup de ces bijoux présentent des affinités avec l’orfèvrerie indienne. Ils n’ont pas de répondant dans le Cambodge classique, ainsi que nous a permis d’en juger un examen approfondi des pièces du Musée de Phnom-Penh et des représentatians des bas-reliefs d’Ankor. Certains procédés d’application du métal se reconnaissent cependant sur des bijoux en cuivre trouvés dans le Bàrày occidental dont le fond contient des vestiges pré-angkoriens. Enfin, il convient de mentionner quelques bagues conservées au Musée Albert Sarraut comme provenant d’Ankor Bórěi, qui offrent une évidente parenté avec certains bijoux d’Oc-èo.

[“The site yielded a great abundance of gold jewelry, small ingots, twisted, curved, flattened or braided wires indicating goldsmith work. They are divided into several series. Necklace beads whose proportions vary from ten millimeters to five tenths of a millimeter, correspond to the same geometric solids as the threading beads made of glass or semi-precious stones. The rings come in very diverse types, from the simple ring to the bezel model enriched or not with precious stones. Some are seals bearing Sanskrit characters. Some are decorated with a small figurine of a squatting humped ox. Other jewelry appears to be pendants or hoop earrings, hinged or not. An incused [ADB: stamped or hammered in, as a design or figure in a coin] medal of the bracteate type bears a laurel-decorated effigy with the name of Antoninus the Pious and the indication of his fifteenth tribunitian power, i.e. 152 AD. A second one, less readable, could possibly be assigned to Marcus Aurelius. Another which has preserved an attachment ring showing a rather crude effigy surrounded by a circle of globules. Other objects are cases, pendants, flowers, rosettes, fittings with filigree decoration and various destinations. Among them we find a gold nail and eyed needles, as well as leaves engraved with characters among whom we recognize an elegant harp player. Many of these jewels have affinities with Indian goldsmithing. They have no counterpart in classical Cambodia, as we have been able to judge from an in-depth examination of the pieces from the Phnom Penh Museum and the representations of the Angkor bas-reliefs. However, certain metal application processes can be recognized on copper jewelry found in the western Bàrày, the bottom of which contains pre-Angkorian remains. Finally, it is worth mentioning some rings kept at the Albert Sarraut Museum as coming from Ankor Bórěi, which offer an obvious relationship with certain jewelry from Oc-èo.”]

In closing, the author concluded that the “Oc-eo culture” was part of the larger Funan civilization:

Un faisceau d’indications concordantes tend ainsi à intégrer la culture d’Oc-èo à celle du Fou-nan et rien parmi nos objets né vient contredire les renseignements reçus des chroniqueurs chinois concernant cet ancien royaume. On peut donc discerner dans la ville d’Oc-èo la première rencontre d’un site founanais et comme elle a livré d’importantes informations sur la vie matérielle, une bonne part de l’obscurité qui régnait sur une civilisation mal connue se trouve ainsi levée. De rares objets chinois ont été recueillis. Toutes les affinités vont vers l’Inde et révèlent une culture mi-autochtone, mi-étrangère, assortie d’apports paléo-khmèrs ou protokhmèrs. La ville maritime d’Oc-èo reliée à la côte par un grand canal avec avant-port et à Tarrière-pays par d’autres canaux reconnus à l’exploration aérienne en 1946, se présente comme un ancien centre industriel et commercial ayant entretenu avec les rivages du Golfe de Siam, la Malaisie, l’Inde et l’Indonésie, l’Iran et certainement la Méditerranée par voie directe ou par intermédiaire, des relations de navigation étendue. Mais ce site n’a livré qu’une part de ses promesses. Des événements constamment adverses ont paralysé nos recherches et c’est sur une note amère qui né laissera indifférent aucun archéologue que s’achèvera le récit des dernières tribulations de la grande cité d’Oc-èo.

[A body of concordant indications thus tends to integrate the culture of Oc-eo with that of Funan and nothing among our objects contradicts the information received from Chinese chroniclers concerning this ancient kingdom. We can therefore discern in the town of Oc-eo the first discovery of a Funan site and, as it provided important information on material life, a good part of the obscurity which reigned over a poorly known civilization is found thus lifted. Rare Chinese objects were collected. All affinities point towards India and reveal a half-indigenous, half-foreign culture, accompanied by paleo-Khmer or proto-Khmer contributions. The maritime city of Oc-èo connected to the coast by a large canal with an outport and to the hinterland by other canals recognized by aerial exploration in 1946, presents itself as an old industrial and commercial center having maintained with the shores of the Gulf of Siam, Malaysia, India and Indonesia, Iran and certainly the Mediterranean by direct or intermediary, extensive navigation relations. But this site only delivered part of its promises. Constantly adverse events have paralyzed our research and it is on a bitter note which will not leave any archaeologist indifferent that the story of the last tribulations of the great city of Oc-èo will end.”]

Back to George Coedès’ article, we highlight his closing remarks:

La diversite chronologique de ces trouvailles prouve une longue occupation du site. Les objets d’origine romaine remontent au lie siecle de l’ere chretienne. Les inscriptions des sceaux emploient une forme de l’ecriture indienne en usage entre le IIe et le Ve siecle. Le cabochon sassanide correspond peut-etre a une periode de l’histoire du Fou-nan pendant laquelle un souverain de souche iranienne regna sur ce pays (milieu du IVe siecle). On n’était renseigne jusqu’ici sur cet ancien royaume hindouise que par quelques textes chinois et de rares inscriptions sanskrites. Les decouvertes de Go Oc Eo permettent de se former une idee beaucoup plus precise de la civilisation du Fou-nan, ainsi que de ses relations exterieures, notamment avec l’Occident mediterraneen. Fou-nan, ainsi que de ses relations exterieures, notamment avec l’Occident mediterraneen. Prenant place chronologiquement à la suite immediate des trouvailles de Pondichery, qui remontent en gros au Ier et au IIe siecle de l’ere chretienne, celles de Go Oc Eo viennent ajouter un maillon à la chaine constituee par les emporia, ou marches ouverts au commerce etranger, enumeres par Ptoleme.

[“The chronological diversity of these finds attests to a long occupation of this site. Objects of Roman origin date back to the 1st century of the Christian era. The seal inscriptions use a form of Indian writing in use between the 2nd and 5th centuries. The Sassanid cabochon perhaps corresponds to a period in the history of Funan during which a sovereign of Iranian origin reigned over this country (mid-4th century). Until now, we were only informed about this ancient Hindu kingdom through a few Chinese texts and rare Sanskrit inscriptions. The discoveries of Go Oc Eo allow us to form a much more precise idea ofthe civilization of Funan, as well as its external relations, particularly with the Western Mediterranean. Fou-nan, as well as its external relations, particularly with the Western Mediterranean. Taking place chronologically immediately following the finds of Pondicherry, which date back roughly to the 1st and 2nd centuries of the Christian era, those of Go Oc Eo add a link to the chain constituted by the emporia, or markets open to trade foreign, listed by Ptolemy.]

Was Oc Eo the port of Cattigara or Kattigare mentioned in the works of early Greek geographers? The debate has been going on for decades amongst historians. Here, we refer to a recent work that seems to bring a clear answer in the controversy. We’re quoting from Kasper Hanus and Emilia Smagur, “Kattigara of Claudius Ptolemy and Óc Eo: the issue of trade between the Roman Empire and Funan in the Graeco-Roman written sources”, in EurASEAA14, Vol I, Ancient and Living Traditions, Papers from the Fourteenth International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, ed. Helen Lewis, Archaeopress, Oxford, ISBN 978−1−78969−506−9 (e‑pdf), p140‑6:

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (Greek: Περίπλους τὴς Ἐρυθράς Θαλάσσης, Latin: Periplus Maris Erythraei) was written by an anonymous author and is dated between AD 40 – 70. Although some elaborations give dates between AD 30 and 230 (e.g. Huntingford 1980), historians incline towards the middle of the first century, based on the chronology of the Nabataean kings presented in the periplus (Casson 1989: 6 – 7). The identity of the author is also controversial. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Schoff (1912) assumed that author was an Egyptian Greek, probably a merchant who lived in Alexandria or Berenice, and this interpretation still has the largest group of followers (e.g. Casson 1989). After Alexander the Great’s conquest, the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty seized and held control of Egypt for almost three hundred years, until 30 BC, when the Battle of Actium was won by Octavius Augustus, and Egypt became a Roman province (Eck 2003). It is very likely that the author personally travelled to India, however his poor writing style (e.g. confusing Latin and Greek words), reveals that he was not well educated (Schoff 1912). The periplus describes the geography and trade relationships in the basin of the Erythraean Sea (Figure 1). In Greek Ἐρυθρά Θάλασσα means Red Sea, but the modern sense of this meaning, being limited to the sea between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula (International Hydrographic Organization 1953: 20), is different than the ancient meaning. In classical written sources, like the periplus, the term Erythra Thalassa corresponded to the whole Indian Ocean, including the Arabian Sea and Persian Gulf. […] East of India the author names a land called Chryse, Χρύση, which means gold/golden, which we believe is an obvious reference to Suvarnabhumi [Sanskrit: सुवर्णभूमी: Land of Gold] [1]. This is first mentioned in chapter 56, where, while describing market towns of the central part of the western Indian coast, it is said that, among other products, tortoise shells are imported from Chryse. The periplus gives us relatively little information about the location of Chryse: ‘And just opposite the river [Ganges] there is an island in the ocean, the last part of the inhabited world toward the east, under the rising sun itself; it is called Chryse; and it has the best tortoise shells of the all places of the Erythraean Sea. After this region under the very north (…) in land called This [China] there is (…) city called Thine’ (The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, chapter 63, Schoff 1912: 48). […]

Ptolemy also refers to Southeast Asia, giving us supplementary details to the older Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. He repeats information about Chrysḗ Chersónēsos, i.e. the Golden Peninsula, which, based on his more precise descriptions, is believed to refer to the Malay Peninsula (Borell et al. 2014), and places the port of Kattigara to the east of that (Schoff 1917). Kattigara is located at Sinus Magna (The Great Gulf), which probably refers to the Gulf of Thailand. It is noted as a port of trade with Sine [China] (Berggren and Jones 2001). The exact geo-referenced location of Kattigara is controversial and several locations have been discussed, including in northern Vietnam and southern China (e.g. Gerini 1909: 303). In our opinion, the most probable location of Kattigara is the archaeological site of Óc Eo in modern An Giang Province of Vietnam. In favor of this theory is the site’s location at the Gulf of Thailand (Figure 3), its role as the port of Angkor Borei (Higham 2014: 279), and finally the enormous concentration of artifacts, such as pendants imitating Roman coins, intaglios in Roman style, a cameo depicting a Sasanian official, and a Han period mirror found at the site, confirming its cosmopolitan character (Malleret 1959, 1960; Borell 2014).

[1] In 2017, Dr. Vong Sotheara from the Royal University of Phnom Penh discovered in Kompong Speu province, Baset district, a stone inscription dating back from 633 CE, written in Sanskrit and Nagari characters, which he translated as: “The great King Isanavarman is full of glory and bravery. He is the King of Kings, who rules over Suvarnabhumi to the sea, which is the border, while the kings in the neighbouring states honour his order to their heads.” The sovereign in question, King Isanavarman I, reigned the Chenla Kingdom 613 – 637 CE. The stela is now at the National Museum of Cambodia. In an interview given to Rinith Taing (Phnom Penh Post, 8 Jan 2018, reposted on KhmerKrom website), Dr. Sotheara claimed there have not been any discovery of stone inscriptions mentioning the term before, either around Southeast Asia or in Sri Lanka.

French Cochinchina (vn Xứ thuộc địa Nam Kỳ, chữ Hán: 處屬地南圻, kh កម្ពុជាក្រោម Kampuchea Krom “Lower Cambodia) was a colony of French Indochina from 1862 to 1946, mostly dedicated to vast rubber plantations, and a high stake in the bitter power struggle between France and Vietnamese nationalists, culminating in June 1949 with the integration of the historic Cambodian provinces into a short-lived “State of Vietnam” theorically led by exiled Emperor Bao Dai.

It took nine years to the French military — from the takeover of Saigon on 17 February 1859 to the Battle of Ky-hoa in February 1861 to Admiral Lagrandiere’s “Vinh-Long Expedition” (ended 23 June 1867) — for securing their control on the Mekong Delta. Yet it was only in 1879 that the first civil Governor of Cochinchina, Le Myre de Villers, was appointed to rule a territory with special status, as Cochinchina was the only stricto sensu colony of Indochina, with its inhabitants considered as French subjects.

The colonial administration defined three regions for this vast territory: East (not including Saigon and Cholon), Center, and West, where the population was mostly Cambodian but was considered “mixed”. Such territorial organization did not take into account the fact that the Mekong Delta had always been a bone of contention between, Siam, Annam and Cambodia. To quote David Chandler’s A History of Cambodia (p 97),

From the 1620s onward, these regions of dissidence could often rely on Vietnamese support. According to the Khmer chronicles, a Cambodian king married a Vietnamese princess in the 1630s and allowed Vietnamese authorities to set up customs posts in the Mekong Delta, then inhabited largely by Khmer but beyond the reach of Cambodian administrative control. Over the next two hundred years, Vietnamese immigrants poured into the region, still known to many Khmer today as Lower Cambodia or Kampuchea Krom. When Cambodia gained its independence in 1953, some four hundred thousand Cambodians still lived in southern Vietnam, surrounded by more than ten times as many Vietnamese. The Khmer residents developed a distinctive culture, and many twentieth-century Cambodian political leaders, including Son Sen, Son Sann, Ieng Sary, and Son Ngoc Thanh, were born and raised as members of this minority. The presence of rival patrons to the west and east set in motion a whipsaw between Thai and Vietnamese influence over the Cambodian court, and between pro-Thai and pro-Vietnamese Cambodian factions in the provinces as well. Already severe in the 1680s,8 this factionalism lasted until the 1860s, and arguably was revived under Democratic Kampuchea, where eastern-zone cadres were accused by Pol Pot and his colleagues of having “Cambodian bodies and Vietnamese minds.”

The French administration had established an “Autonomous Republic of Cochinchina” after the end of Japanese occupation (1941 – 45) and the expulsion from Saigon of the nationalist Viet Minh in 1946, and tried to counter the territorial claims of the Hanoi Democratic Republic of Vietnam” (proclaimed in 1949) by uniting Cochinchina, Annam and Tonkin in the “State of Vietnam” within the French Union.

In the new Territorial Assembly of Cochinchina, founded on 14 March 1949, factions close to the South Vietnamese activists and French colonists lobbyed against the integration into Vietnam, while eying the Cambodian provinces of the Mekong Delta. The Cambodian government, not privy the French-Vietnamese tractations, attempted to prevent the deal in extremis, sending to Paris a delegation led by Son Sann and Prime Minister Chhean Vam. To no avail: on 4 June 1949, French President Vincent Auriol signed the law granting Cochinchina to the Bao Dai régime, without consultation with the Khmer-Krom population.

South Vietnamese President Diem — King Sihanouk’s nemesis — conducted a systematic ‘Vietnamization’ of the Cambodians in the area, implementing in 1956 a compulsory Vietnamese identity card for these communities, now called “Người Việt Góc Miên” (Vietnamese of Khmer Origin) in official documents. He also launched the “Cải Cách Điền Địa” (Farmland Reform), aiming at taking over Cambodian farmlands and granting them to Vietnamese newcomers. Unsurprisingly, villagers and Buddhist monks launched protest movements such as the “Free Khmer” (Khmer Serei), formed in the Binh Long (formerly Toul Ta Mok) province in 1958, or the Khmer Con Sen Sar (Khmer White Scarves), initiated in 1959 in Chau Doc (Mout Chrouk) province.

While officially numbered at 1.34 millions in the 2019 Vietnamese census, the number people of Khmer-Krom origin in the Mekong Delta have been estimated to be much higher.

Tags: Oc Eo, Roman Empire, numismatic, archaeology, Oc Eo culture, Cochinchina, Vietnam, canals, Funan, material culture, jewelry, coins, medals, inscriptions, French Cochinchina

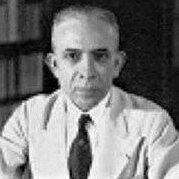

George Cœdès (to be pronounced Zsedes) (10 Aug 1886, Paris, France – 2 Oct 1969, Paris) was a leading archeologist, linguist and historian in the field of Khmer studies.

He was still a high-school student at Paris Lycée Carnot when he learnt Sanskrit and Khmer, publishing in 1904, one year after the baccalaureate, his very first article in the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient: “Inscription de Bhavavarman II roi du Cambodge (561 çaka)”. A frequent visitor to Musée Guimet library, he completed his studies in German language and literature while focusing on Sanskrit and “Oriental” studies under Albert Foucher, Louis Finot, and Sylvain Lévi. He moved to Hanoi in January 1912, and to Phnom Penh in March that same year, joining EFEO in 1913 and becoming a leading epigraphist of Cambodian inscriptions, a philologisit and art historian in Thai, Cambodian, Laotian, Malay, Javanese and Annamese cultures.

Coedès visited Angkor for the first time in May 1912, with then-conservator Jean Commaille. That same year, he married a young Cambodian woman, Neang Yap, introduced to him by then-Minister of War, Education and Public Works, Peich Ponn, Yap’s uncle, when she was 16. Their Cambodian civil marriage was registered at Bangkok French Consulate in 1918. Since Peich Ponn was married to one of King Norodom’s daughters, Coedès’s young wife was vinculated to the Cambodian Royal family [see Marie Aberdam, Élites cambodgiennes en situation coloniale, 2019; Bernard Cros, Péninsule 82, 2021; G. Coedès, “Saṃdằč Čakrĕi Péč Pŏn (1867−1932)”, BEFEO 33, 1933: 561 – 562]. According to Thai historian M.C. Subhadradis Diskul, the union also made his access to the Siamese high society easier, as Miss Yap had family connections with one of Prince Rajanubhab Damrong’s wives. [สภุ ัทรดิศ ดิศกลุ, ศาสตราจารย์ ยอร์ช เซเดส์ [Professor George Coedès], วิทยาสาร ปริทัศน์ [Scientific Journal Review] April 1970. : 10‒13, 62‒63, 68, quoted in Jean Baffie,“George Coedès (1886 – 1969)”, JSS 113 [Special Edition], 2025: 109 – 33.]

1) Minister Peich Ponn. 2) Neang Yap and George Coedès in 1912. [source: photos from AFC (Coedès Family Archive, published in B. Cros, “Coedès et le Cambodge…”, 2021, op. cit.

After returning briefly to Hanoi, he came back to Cambodia in 1914, contributing to the creation of the School of Pali in Phnom Penh. He then moved to Bangkok with his wife, and the couple had five of their six daughters born there (Jeanne in 1917, Yvonne in 1918, Lucie in 1919, Suzanne in 1921 and Simone in 1922) [1]– Prince Damrong, whom he accompanied in his first visit to Angkor in 1919, noted in his travelogue that “Prof. Coedès’ young wife, Asarai [?], took her children” with them for the trip.

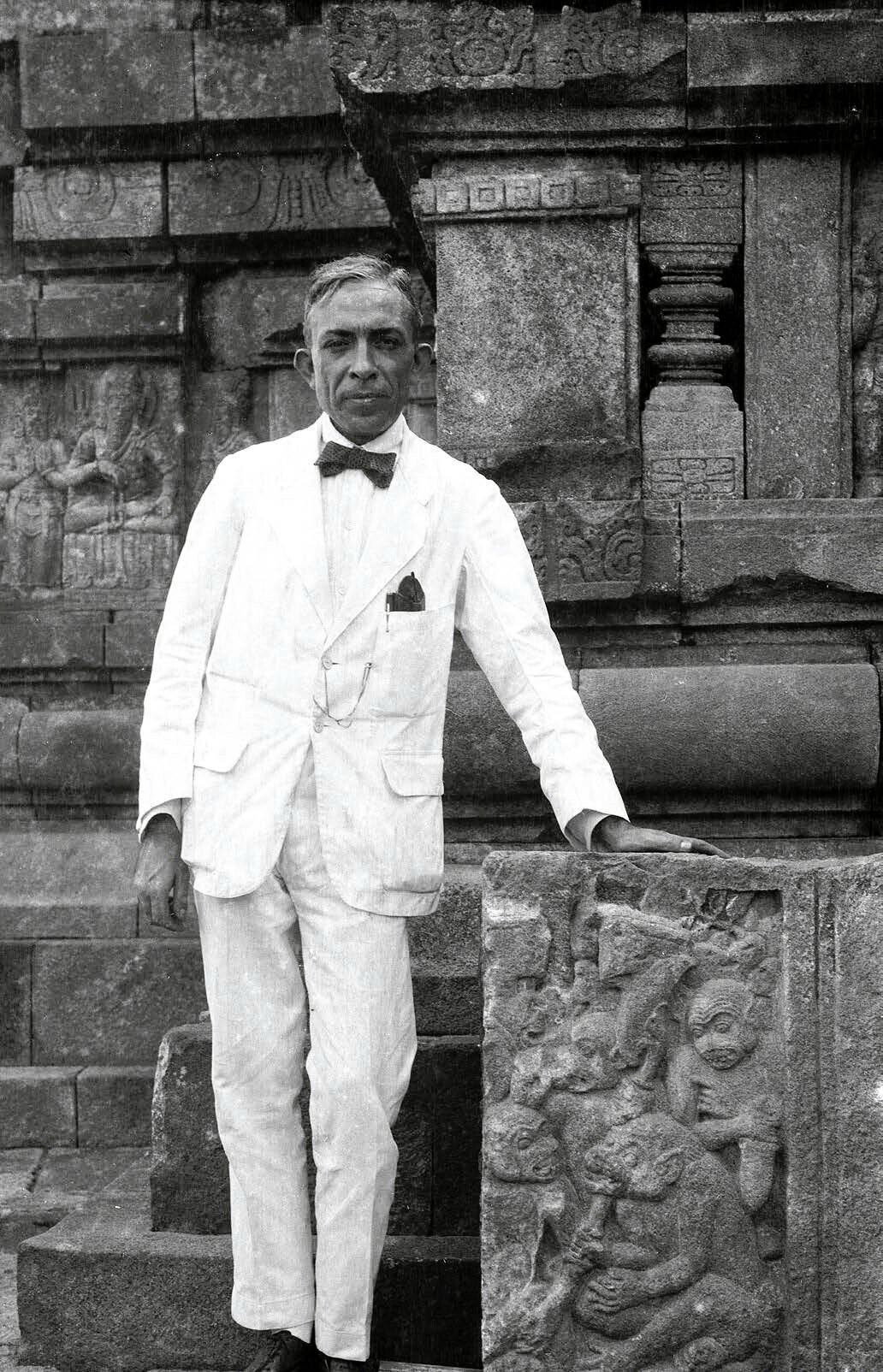

Director of the National Library of Siam from 1918 to 1928, he became director of EFEO in 1929, until 1946. In Bangkok, he had been appointed secretary of the Institute of Literature, Archaeology and Fine Arts founded by Prince Damrong in April 1926. Representing the Institute during a visit to Batavia in 1928, Coedès learnt about the ‘anastylosis’ restoration technique from Dutch archaeologist Pieter Van Stein Callenfels, and invited Henri Marchal to apply it to Khmer monuments two years later, when he headed EFEO.

A specialist in the history of Indo-Chinese ´Indianized kingdoms´, he wrote The Indianized States of Southeast Asia (1968, 1975, first published in 1948 in French as Les états hindouisés d’Indochine et d’Indonésie) and The Making of South East Asia (1966). He was also a leading researcher in Sanskrit and Old Khmer inscriptions from Cambodia.

Professor George Cœdès is also credited with rediscovering the former kingdom of Srivijaya (modern Palembang), which was influent from Sumatra to the Malay Peninsula and Java. The matter remains debated to tjhese days. All in all, as researche Pierre-Yves Manguin noted in 2025,

“Coedès himself recognized, albeit late in his career, the limitations of his generation of Orientalist approaches. In a lecture to the Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres [2], he acknowledged that the social and economic structures of Southeast Asian societies remained poorly understood, and he urged younger researchers trained in the social sciences to take up the challenge (Coedès 1960). More than half a century later, this call is finally being answered.” [Pierre Yves-Manguin, “George Coedès and Śrīvijaya: From Epigraphy to Archeology”, JSS 113 [Special Edition George Coedès], 2025, p. 164].

In the 1960 conference above mentioned, George Coedès was in effect foreseeing the upcoming contributions by younger researchers, in particular Claude Jacques, Michael Vickery, Saveros Pou, Au Chhieng and Ang Choulean:

L’épigraphie en langue khmère permettra l’étude d’une série de questions qui n’ont encore jamais été abordées. Elle éclairera tout un côté de la vie du peuple absolument étranger au monde qu’ont fait connaître jusqu’ici les inscriptions sanskrites, un monde très éloigné des fastes de la Cour d’Angkor et des fondations de monuments prestigieux par le roi et ses grands dignitaires, dont les inscriptions sanskrites se plaisent à faire l’éloge en termes poétiques. Tout ce menu peuple, dont on vient de voir les démêlés et les soucis quotidiens, né joue pratiquement aucun rôle dans l’épigraphie en langue savante. C’est pourtant lui qui, à la sueur de son front, a procuré au pays sa richesse, sa prospérité, favorisant ainsi l’épanouissement de sa civilisation. Peut-être le moment est-il venu de lui accorder quelque attention, en utilisant le trésor encore inexploité des inscriptions rédigées à son intention dans sa propre langue.

[Epigraphy in the Khmer language will foster the study of many subjects that have never before been addressed. It will shed light on an entire aspect of people’s lives of completely foreign to the world known until now through Sanskrit inscriptions, a world far removed from the splendor of the Angkor court and the foundations of prestigious monuments by the king and his high dignitaries, whom Sanskrit inscriptions so poetically praise. All these ordinary people, whose daily struggles and concerns we have just seen, play practically no role in epigraphy in the learned language. Yet it is they who, through the sweat of their brow, have brought wealth and prosperity to the country, thus fostering the flourishing of its civilization. Perhaps the time has come to pay them some attention, by utilizing the still untapped treasure of inscriptions written for them in their own language. [“L’avenir des études khmères”, Comptes-rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres (AIBL) 104e année, 1960, p. 374].

[1] Neang Yap and George’s two sons, Pierre (1914−2025) and Louis (1915−1998), were to come back to Cambodia in the 1950s, Pierre Coedès as Director of the Cambodian Merchant Navy — at the suggestion of King Norodom Suramarit himself –, Louis to launch a private bank in Phnom Penh.

[2] “L’avenir des études khmères”, Comptes-rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres (AIBL) 104e année, 1960, p. 367 – 374.

As Director of EFEO in Hanoi, 1940s [photo CAM19999 © EFEO].

1) 1) In Prambanan, Indonesia, Aprill 1928 [© Archives familiales Coedès, rep. in B. Cros, “George Coedès à Batavia (1928), JSS 113, op. cit., p. 174.] 2) On 14 Feb. 1958, day of his election to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Paris [© AIBL, repr. in Jean Baffie, JSS 113, op. cit., p. 121.]

1) 1) In Prambanan, Indonesia, Aprill 1928 [© Archives familiales Coedès, rep. in B. Cros, “George Coedès à Batavia (1928), JSS 113, op. cit., p. 174.] 2) On 14 Feb. 1958, day of his election to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Paris [© AIBL, repr. in Jean Baffie, JSS 113, op. cit., p. 121.]

1) 1) In Prambanan, Indonesia, Aprill 1928 [© Archives familiales Coedès, rep. in B. Cros, “George Coedès à Batavia (1928), JSS 113, op. cit., p. 174.] 2) On 14 Feb. 1958, day of his election to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Paris [© AIBL, repr. in Jean Baffie, JSS 113, op. cit., p. 121.]

George Coedès was a prolific author. The most exhaustive attempts to a complete bibliography was presented by A. Zigmund-Cerby and J. Boisselier in “Travaux de M. George Coedès. Essai de Bibliographie”, Artibus Asiae, 1961, vol. 24−3÷4, pp.155 – 186, and by Jean Filliozat (“Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. George Coedès, BEFEO 1970, Vol. 57 (1970), pp. 1 – 24). Here is the latter bibliography, more up-to-date and excluding the numerous recensions by Coedès:

References

sk काम्बोज kāmboja | prakrit कंबोय | [कम्बुजदेशः kambujadesa, 'land of Kambuja' | oldkh កម្វុជទេឝ, midkh កម្ពុជទេស mkh កម្ពុជា kampuchea, Cambodia

sk नागरी nāgarī, "small town", "master of the town", "heroine"; from sk nagara.

Nāgarī is an Indian script first used to write Prakrit and Sanskrit and widely used during the first millenium CE. Some scholars view it as the ancestor of other scripts such as Devanagari (deva-nāgarī) and Nandinagari, while other linguists consider Nāgarī and Devanāgarī as the same script.

Nāgarī is a Sanskrit technical term used in ancient Indian astronomy, mathematics and geometry. In Shaktism, it refers to one of the eight Servants associated with the "churning" (manthāna).

The Nāgarī script, a left-to-right abugida (segmental writing system), has roots in the ancient Brahmi script family.

Devanagari देवनागरी, already widely used by the 8th century CE, reached its modern form - 48 primary characters, including 14 vowels and 34 consonants - by 1000 CE. It is the fourth most widely adopted writing system in the world, being used for more than 120 languages, in particular Hindi (हिंदी).

Note: Several names of towns or cities mentioned in Khmer inscriptions written in Sanskrit end with the suffix -nagari, for instance Jayantanagari, "the victorious city" (K. 908) [a city in which Jayavarman VII placed a Buddha image] or Jayendranagari, "the city of the victorious lord" (K.255) [a palace founded by King Jayavarman V, possibly near Prasat Baphuon, Angkor Thom].

sk सुवर्णभूमि , pl Suvaṇṇabhūmi, kh នសុវណ្ណភូមិ sovanaphum th สุวรรณภูมิ swrnphumi

Suvarṇabhūmi is an Eastern "golden kingdom" often mentioned in ancient Indian literary sources such as the Ramayana and Milinda Panha, as well in Buddhist sacred texts, Mahavamsa and Jataka tales.

While modern scholars such as Ian Glover insisted that it was an "idealised place", a mythical region akin to the Atlantis or the "Land of Milk and Honey" in Western traditions, the place was an actual destination for Indian traders sailing to the East. Several places in modern Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia, and also Sri Lanka, Sumatra and Borneo, have been speculated to be the genuine location of Suvarnabhumi.

In 2017, Dr. Vong Sotheara from the Royal University of Phnom Penh discovered in Kompong Speu province, Baset district, a stone inscription dating back from 633 CE, written in Sanskrit and Nagari characters, which he translated as: “The great King Isanavarman is full of glory and bravery. He is the King of Kings, who rules over Suvarnabhumi until the sea, which is the border, while the kings in the neighbouring states honour his order to their heads.” The stela is now at the National Museum of Cambodia.

Earlier, researcher George Coedès had suggested that Suvarnabhumi could have been, in its Chinese pronunciation, the root of the word 'Funan', the ancient kingdom in Southern Cambodia.