Rêveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes [Musings on the Cambodian Dancers]

by Francis Miomandre (de)

The perception of the Cambodian dancers in 1920s and 1930s Paris, by a famed art critic and his detractors.

- Publication

- La Danse, n 38 (Nov. 1923), Paris (15 av. Montaigne).

- Published

- November 1923

- Author

- Francis Miomandre (de)

- Pages

- 2

- Language

- French

pdf 559.9 KB

Starting with the 1906 historic visit of King Sisowath to France and the performances of the Royal Ballet’s dancers in Paris and Marseille that bewitched the general public — and the formidable figure of artist Auguste Rodin -, the Cambodian dance form stimulated the French discussion on “primitive” and “classical” arts, on what was “exotic” and what ought to be considered as global cultural heritage, the latter notion not having been yet formulated at the time. The following essay was an important contribution.

Reveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes (1923)

Text by Francis de Miomandre, drawings by “A. De Roux” [probably Antoine de Roux (1901−1986), a French illustrator who later draw many color illustrations in color for fashion and lifestyle magazines.] ADB English translation below.

S’il est vrai, coumne l’a dit Spinoza, que l’art est “I’homme ajouté à la nature”, il n’y a peut-être pas d’art plus authentique, plus pur, plus digne de ce nom que l’art de l’Extrême Orient. Et nous en eumes la confirmation éclatante avee ces admirables ballets cambodgiens, que l’Opéra nous a donnés, naguère, seulement deux fois. Jamais je n’avais rien vu de plus arbitraire, de plus formulé, de plus définitivement fixé au-dessus et en dehors de toute fantaisie. C’est saisissant.

+++

C’est même déconcertant. Le public visiblement perd pied. Il suit mal les péripéties de ces pantomimes extraites d’un poème si vieux (la plupart du temps le Ramayana). Il s’énerve de cette musique aigüe à la fois et cristalline, insinuante, qui endort par sa monotonie et réveille par son acidité. Mais qu’importe ici son étonnement? Tout art étranger dans lequel on entre de plain-pied né valait pas la peine de nous être révélé. Ce qui est intéressant c’est justement cet exotisme étrange et, au delà de l’exotisme, au delà de l’enchantement immédiat des sens, cette impression “spirituelle”, de rêve. Peu de danseuses m’ont fait penser à ce point. Que l’ou comprenne ou non la fable, un monde de réflexions se soulève, à l’appel incantatoire de leur geste souple.

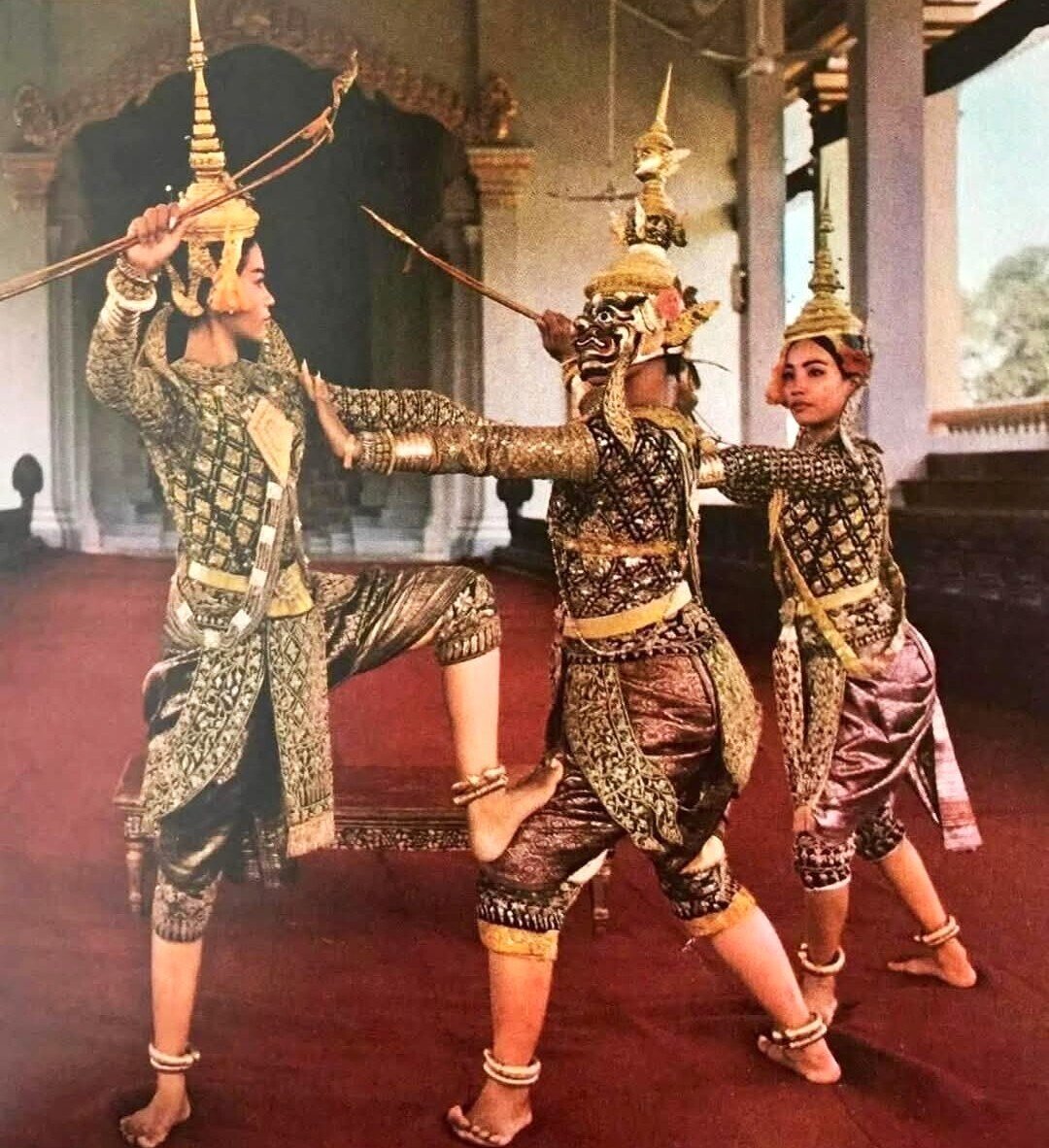

Et tout d’abord, je pense à la différence essentielle des deux arts chorégraphiques: celui d’Orient et celui d’Occident. Elle est tellement caractéristique! Chez nous, en Occident, le danseur sauté. Ce sont les jambes qui mènent le jeu, ce sont elles qui sont chargées d’exprimer la pensée du poète. Le corps les suit, pour ainsi dire porté par elles, et les bras, même dans leurs mouvements les plus difficiles ou les plus expressifs, né sont là que comme un accompagnement ornemental, une arabesque.

En Orient, c’est l’inverse. Le danseur est volontiers inmobile. Les bras seuls bougent, et le buste. Ce sont eux qui rendent le sentiment et la pensée, suivant mille nuance correspondant à d’imperceptibles variations. Cela seul suffit à nous faire mesurer la superiorité d’un art sur l’autre. Celui d’Orient ext terriblement plus ancien, plus raffiné. La danse “saltatrice” est une expression très primitive du sentiment. On la retrouve chez les peuples les plus sauvages. Elle correspond, en effet, à des sensations brutes, massives, confuses. Nos chorégraphes occidentaux ont compliqué cela à l’infini, ils ont même pensé (et ceci était une intuition juste) à en faire une sorte d’algébre, de langage conventionnel. Mais ils n’ont pas eu l’idée de toucher au principe même, ils n’ont pas songé a remonter plus haut. Les chorégraphes orientaux, eux, ont hardiment renversé les données du problème et, réduisant le rôle des jambes à quelques marches rythmiques, rituelles, ils ont conflé aux bras (dès lors désossés, désarticulés a l’extrême possible) le soin de danser. Cétait un coup de génie.

Cela date bien entendu de très loin. C’est immémorial. Tels qu’ils nous sont parvenus, intacts à travers les siècles, les ballets cambodgiens représentent une formule d’art très évoluée, estimée assez parfaite pour devenir définitive. Nimporte, cela suffit pour faire juger le tact esthétique d’une race, son intelligence prodigieuse du monde de la sensibilité Les danses cambodgiennes, du fait seul qu’elles se limitent ainsi au buste et aux bras, révèlent le choix qu’elles font entre les sentiment à exprimer. Délibérément, elles rejettent tout ce qui rapporte à la sensation, pour se consacrer à exprimer des états d’âme, des pensées, des rêves. Chez nous, cette agitation constante de la ballerine, charmante certes et souvent délicieuse, maintient toute la chorégraphie sur un plan malgré tout inférieur, le confine pour ainsi dire dans le domaine de l’anecdote. A tout instant, la ballerine orientale suggère des idées, des sentiments à l’état par, allégés de leur réalisation de fait. Elle évolue dans le riche royaume de la vie intérieure. Algèbre? oui certes! mais combien subtile et délicate, combien mouvante et sensible malgré son apparence si fixée! combien intelligible surtout à qui veut, non pas même se donner la peine de comprendre, mais seulement se laisser aller à la magie incantatoire de ces gestes, de ces attitudes d’une grace souveraine, d’une perfection émouvante.

Chacun de ces gestes, chacune de ces attitudes est une synthèse de cent autres moins pures, plus capricieux, que la nature avait fournis, mais le tact avec lequel cette synthèse a été faite est si merveilleux que lorsqu’ils sont dessinés dans l’air, ils nous suggèrent aussitôt tous les autres, ils suscitent en notre souvenir tous ceux dont ils sont le résumé, la forme idéale et définitive, la clef. J’aurais voulu que tous ces gens qui nous rebattent les oreilles depuis quinze ans avec “l’art classique” aient vu les ballets cambodgiens. Ils auraient compris ce que c’est qu’un art classique dans ces oeuvres où l’émotion est à son comble mais enfermée, maintenue conservée et comme scellée dans une pensée. La passion dans la rigueur de l’ordre, n’est-ce point là ce que les anciens prisaient si fort sous le nom de décence? Je n’ai jamais rien vu de plus décent que l’art des danseuses cambodgiennes.

+++

Ah! comme Mallarmé, qui se faisait de la danse une idée si haute, si pure, aurait aimé ces prêtresses enfants, ces petites vestales serpentines, vêtues d’or, écrivant de leurs mains merveilleuses, sans arrèt, sur le fond pur du décor spirituel tant de pensées, tant de sentiments et tant de rêves…

[If Spinoza had it right when he said that art is “man added to nature,” there is perhaps no art more authentic, more pure, more worthy of the name than the art of the Far East. And we had striking confirmation of this with those admirable Cambodian ballets, which the Opera performed for us only twice recently. I have never seen anything more arbitrary, more formulated, more definitively fixed above and beyond all fantasy. It’s striking.

+++

It’s even disconcerting. The audience is visibly losing its footing. Spectators struggle to follow the twists and turns of these scenes taken from such an ancient poem (mostly from the Ramayana). They become irritated by this high-pitched, crystalline music, insinuating, which lulls with its monotony and awakens with its acidity. But what does his astonishment matter here? Any foreign art that one enters directly into was not worth revealing to us. What is interesting is precisely this strange exoticism and, beyond the exoticism, beyond the immediate enchantment of the senses, this “spiritual” impression, that of a dream. Few dancers have made me think to this extent. Whether or not one understands the fable, a world of reflection arises at the incantatory call of their supple gestures.

And first of all, I think of the essential difference between the two choreographic arts: that of the East and that of the West. It is so characteristic! In our country, in the West, the dancer jumps. It’s the legs that call the shots; they’re the ones responsible for expressing the poet’s thoughts. The body follows them, carried by them, so to speak, and the arms, even in their most difficult or expressive movements, are there only as ornamental accompaniment, an arabesque.

In the East, it is the opposite. The dancer is willingly immobile. Only the arms move, and the torso. They are the ones who convey feeling and thought, following a thousand nuances corresponding to imperceptible variations. This alone is enough to make us measure the superiority of one art over the other. That of the East is terribly older, more refined. The “” dance is a very primitive expression of feeling. It is found among the most savage peoples. It corresponds, in fact, to raw, massive, confused sensations. Our Western choreographers have complicated this to infinity; they have even thought of — and this was a correct intuition — making it some kind of algebra, a conventional language. But they didn’t think to touch the very principle, they didn’t think to go back further. Oriental choreographers, for their part, boldly reversed the givens of the problem and, reducing the role of the legs to a few rhythmic, ritualistic steps, they entrusted the arms (henceforth boneless, disarticulated to the extreme possible) with the task of dancing. It was a stroke of genius.

This, of course, dates back a very long time. It is immemorial. As they have come down to us, intact through the centuries, Cambodian ballets represent a highly evolved artistic formula, considered perfect enough to become definitive. Regardless, this is enough to judge the aesthetic tact of a race, its prodigious intelligence of the world of sensitivity. Cambodian dances, by the very fact that they thus limit themselves to the bust and arms, reveal the choice they make between the feelings to be expressed. They deliberately reject everything related to sensation, devoting themselves to expressing moods, thoughts, and dreams. In our dance, this constant restlessness of the ballerina, charming indeed and often delightful, maintains the entire choreography on a lower plane, confining it, so to speak, to the realm of anecdote. At every moment, the oriental ballerina suggests ideas, feelings in a pared-down state, relieved of their actual realization. She moves in the rich realm of inner life. Algebra? Yes, certainly! But how subtle and delicate, how shifting and sensitive despite its fixed appearance! How intelligible, especially to anyone who is willing, not even to take the trouble to understand, but simply to surrender to the incantatory magic of these gestures, these attitudes of sovereign grace, of moving perfection.

Each of these motions, each of these attitudes, is a synthesis of a hundred others, less pure, more capricious, that nature had provided, but the tact with which this synthesis has been made is so marvelous that when they are drawn in the air, they immediately suggest all the others to us, they arouse in our memory all those of which they are the summary, the ideal and definitive form, the key. I would have liked all these people who have been droning on about “classical art” for fifteen years to have seen the Cambodian ballets. They would have understood what classical art is in these works where emotion is at its peak but locked away, kept preserved and as if sealed in a thought. Passion within the strictest order — is that not what the ancients prized so highly under the name of decency? I have never seen anything more decent than the art of Cambodian dancers.

+++

Ah! How Mallarmé, who had such a lofty, pure idea ofdance, would have loved these child-priestesses, these little serpentine vestals, dressed in gold, writing with their marvelous hands, endlessly, against the pure backdrop of the spiritual setting, so many thoughts, so many feelings, and so many dreams…]

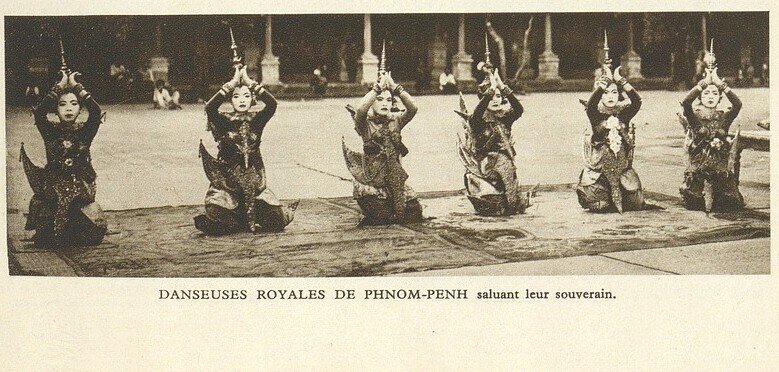

1/ Female deity (devata) in dance, 12th or13th century, coll. Aziz Bassoul in “Bronzes royaux d’Angkor” exhibition at Paris Musee Guimet (photo DR) | 2/ Illustration by A. de Roux for “Reveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes” | 3/ ‘Kinnari’ dancer at Phnom Penh Royal Palace in the 1920s, photo by Martin Hürliman | 4/ Not only “arms and torso”: a dance performance at the Chanchaya Pavilion, undated archive photo shared by Sovannou Dom.

1/ Female deity (devata) in dance, 12th or13th century, coll. Aziz Bassoul in “Bronzes royaux d’Angkor” exhibition at Paris Musee Guimet (photo DR) | 2/ Illustration by A. de Roux for “Reveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes” | 3/ ‘Kinnari’ dancer at Phnom Penh Royal Palace in the 1920s, photo by Martin Hürliman | 4/ Not only “arms and torso”: a dance performance at the Chanchaya Pavilion, undated archive photo shared by Sovannou Dom.

1/ Female deity (devata) in dance, 12th or13th century, coll. Aziz Bassoul in “Bronzes royaux d’Angkor” exhibition at Paris Musee Guimet (photo DR) | 2/ Illustration by A. de Roux for “Reveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes” | 3/ ‘Kinnari’ dancer at Phnom Penh Royal Palace in the 1920s, photo by Martin Hürliman | 4/ Not only “arms and torso”: a dance performance at the Chanchaya Pavilion, undated archive photo shared by Sovannou Dom.

1/ Female deity (devata) in dance, 12th or13th century, coll. Aziz Bassoul in “Bronzes royaux d’Angkor” exhibition at Paris Musee Guimet (photo DR) | 2/ Illustration by A. de Roux for “Reveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes” | 3/ ‘Kinnari’ dancer at Phnom Penh Royal Palace in the 1920s, photo by Martin Hürliman | 4/ Not only “arms and torso”: a dance performance at the Chanchaya Pavilion, undated archive photo shared by Sovannou Dom.

1/ Female deity (devata) in dance, 12th or13th century, coll. Aziz Bassoul in “Bronzes royaux d’Angkor” exhibition at Paris Musee Guimet (photo DR) | 2/ Illustration by A. de Roux for “Reveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes” | 3/ ‘Kinnari’ dancer at Phnom Penh Royal Palace in the 1920s, photo by Martin Hürliman | 4/ Not only “arms and torso”: a dance performance at the Chanchaya Pavilion, undated archive photo shared by Sovannou Dom.

Cambodian or “Oriental”? A confusing controversy

Miomandre had quite audaciously argued that the Cambodian dance was in fact less “raw” and primitive than Western classical choreography. Moreover, in demonstrating that this art form inscribed itself consciously in a particular cultural tradition and in an idiosyncratic worldview, he implicitely challenged the category of “exotic dance”, a bundle of non-European expressions that went to include everything from the North African Berber folk dances to the Japanese theater to the irruption of American Black culture through jazz. And his claim that he had never seen anything more “decent” than Cambodian dance, he was responding to the widespread notion that “exotic” was just another word for “erotic” — a confusion that would culminate in the USA with exotic dance locales becoming nothing less than strip joints.

His essay was immediately attacked by the influential dance critic André Levinson. In a short pamphlet published in Comoedia (“La connaissance de l’Est”, 31 Dec. 1923 [via gallica.bnf.fr]), Levinson decried this

réquisitoire contre la danse classique, qu’il immole sans regrets sur l’autel de ses petites idoles aux tiares d’or…N’est-il pas vain d’affirmer que le sanscrit du Ramayana est plus beau que le latin de l’Eneide? Or, la danse cambodgienne est un enchainement de gestes expressifs et de figures, reduits à des formules plastiques stables et completes; c’est une pantomime qui évolue vers la danse. L’étoile d’Occident s’exprime en un langage abstrait de formes. Si les réalisations de nos danseuses sont infiniment moins parfaites que celles des Cambodgiennes, le principe de leur art est, par definition, plus pur. […indictment of classical dance, which he sacrifices without regret on the altar of his little idols with golden tiaras...Is it not vain to affirm that the Sanskrit of the Ramayana is more beautiful than the Latin of the Aeneid? Now, Cambodian dance is a sequence of expressive gestures and figures, reduced to stable and complete plastic formulas; it is a pantomime that evolves towards dance. The star of the West expresses itself in an abstract language of forms. If the achievements of our dancers are infinitely less perfect than those of the Cambodians, the principle of their art is, by definition, purer.]

This dubious exercice in comparing merits and degrees of evolution of radically different cultures was expanded in an awkward attempt to celebrate a so-called “Oriental dance”, referring to two Japanese performers then extremely popular in Paris and their “admirable physique of Asiatic ephebes” (along with African dancer Habib Benglia, for good measure):

L’esprit de la danse orientale rayonne sur un territoire immense; il règne sur deux continents et déborde sur le notre. Ainsi l’ineffable souvenir des Cambodgiennes plana, dans un halo d’apothéose, sur le spectacle dansé par deux jeunes Japonais, Toshi Komori et Sakal Ashida, au Vieux-Colombier. [The spirit of oriental dance shines across an immense territory; it reigns over two continents and spills over into our own. Thus, the ineffable memory of the Cambodian women hovered, in a halo of apotheosis, over the dance performance by two young Japanese, Toshi Komori and Sakal Ashida, at the Vieux-Colombier.]

In her in-depth study on the French perception of exoticism and dance in the 1920s and 1930s, Anne Decoret-Ahiha [1] noted that

les danses exotiques étaient celles qui manifestaient une altérité radicale autant dans leur gestuelle que dans les corporalités qui les produisaient. […] “Avoir vu danser un indigène, c’est presque avoir visité son pays”, assurait André Levinson; “Rien né vaut la danse, son dionysiaque appel, pour faire remonter à la surface les secrets de son peuple.” [p 151, 154]

In the same paper, she went back in detail to the particular “saga” of the Cambodian dancers in France:

Le feuilleton du ballet royal du Cambodge, inscrit au programme des Expositions coloniales de Marseille en 1906 et 1922, de Paris en 1931, montre combien l’authenticité relève d’une construction qui peut servir des enjeux idéologiques. Chargé de l’organisation des attractions de l’Indochine pour l’Exposition coloniale de Marseille de 1906, un certain Georges Bois avait eu l’idée de faire venir les danseuses de la cour royale de Phnom Penh. Après moult péripéties, il réussit à obtenir du souverain Sisowath qu’il laissât voyager sa troupe en France, ce dernier les accompagnant également (Bois, 1913). Leurs spectacles comptèrent parmi les attractions les plus prisées et connurent un véritable triomphe. Deux représentations furent même organisées à Paris, d’abord lors de la garden-party de l’Elysée, puis au Théâtre de verdure du pré-catalan. Fort de ce succès, les commissaires des Expositions coloniales de Marseille, en 1922, puis de Vincennes, en 1931, programmèrent à nouveau les célèbres danseuses cambodgiennes. A chaque fois, le public, dont l’enthousiasme frisa parfois l’hystérie, considéra qu’il avait affaire à une authentique troupe royale qui existait et s’épanouissait telle quelle au Cambodge.

Les ballets cambodgiens, “tels qu’ils nous sont parvenus [sont restés] intacts à travers les siècles” assurait Francis de Miomandre (1922). En réalité, la configuration du ballet était, pour chacune de ses apparitions, le résultat d’interventions et de choix propres aux autorités coloniales françaises. En effet, depuis l’instauration du protectorat en Indochine, le ballet, institution attachée au souverain, avait perdu de sa magnificence. C’est l’initiative de Georges Bois qui contribua à réactiver son activité, tout en transformant certains des modes de fonctionnement. Traditionnellement entretenues par le roi, les danseuses perçurent ainsi une rémunération mensuelle, le temps de leur séjour. Mais quelque temps plus tard, le ballet déclina à nouveau. Pour l’Exposition de 1922, on réussit à réunir un petit groupe de danseuses mais cela fut impossible en 1931. Les organisateurs de la grande “fête” coloniale de Vincennes acceptèrent cependant la proposition d’une ancienne danseuse royale, Say Sangvann, qui avait fondé une troupe privée et se produisait devant des touristes. A l’affiche des animations, son groupe fut néanmoins officiellement présenté comme l’authentique ballet royal. C’est qu’en admettant qu’ils avaient engagé des artistes indépendants, les autorités françaises auraient dû reconnaître leur échec dans l’une des missions revendiquées par la colonisation : protéger le splendide patrimoine indochinois des méfaits du temps et de la barbarie indigène.

Quant au spectacle en lui-même, il fut aussi à l’occasion reconfiguré de manière à produire une impression d’authenticité. Ainsi, pour la représentation que le Ballet accepta de donner en 1922, au Palais Garnier, le décorateur du lieu imagina un cadre scénographique censé rendre le spectacle plus authentique. Il conçut un décor lumineux assez chargé, à motifs sylvestres, que l’on né trouve pas dans la tradition chorégraphique cambodgienne. La quête d’authenticité concernant les spectacles exotiques relevait d’une « nostalgie impérialiste », cette forme de nostalgie particulière engendrée par le colonialisme et qui consiste à regretter la disparition de ce qui a été détruit ou transformé par l’oeuvre colonisatrice, masquant de cette manière les rapports de domination, parfois brutaux, que celle-ci implique.

[The French saga of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, included in the program of the Colonial Exhibitions of Marseille in 1906 and 1922, of Paris in 1931, shows how authenticity is a construct that can serve ideological stakes. Responsible for organizing the attractions of Indochina for the Colonial Exhibition of Marseille in 1906, a certain Georges Bois came up with the idea ofbringing the dancers of the royal court of Phnom Penh. After many adventures, he succeeded in obtaining from the sovereign Sisowath that he allow his troupe to travel to France, the latter also accompanying them. Their shows were among the most popular attractions and enjoyed a real triumph. Two performances were even organized in Paris, first during the garden party of the Elysée, then at the Théâtre de verdure of the pre-Catalan. Buoyed by this success, the curators of the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseille in 1922, and then in Vincennes in 1931, once again programmed the famous Cambodian dancers. Each time, the audience, whose enthusiasm sometimes bordered on hysteria, presumed they were dealing with an authentic royal troupe that existed and flourished as such in Cambodia.

Cambodian ballets, “as they have come down to us [have remained] intact through the centuries,” assured Francis de Miomandre (1922). In reality, the configuration of the ballet was, for each of its appearances, the result of interventions and choices specific to the French colonial authorities. Indeed, since the establishment of the protectorate in Indochina, ballet, an institution attached to the sovereign, had lost some of its magnificence. It was Georges Bois’s initiative that helped revive its activity, while also transforming some of its operating methods. Traditionally supported by the king, the dancers received a monthly salary for the duration of their stay. But some time later, the ballet declined again. For the 1922 Exposition, a small group of dancers was successfully assembled, but this proved impossible in 1931. The organizers of the great colonial “festival” in Vincennes, however, accepted the offer of a former royal dancer, Say Sangvann, who had founded a private troupe and performed for tourists. On the bill, her group was nevertheless officially presented as the authentic royal ballet. By admitting that they had hired independent artists, the French authorities should have acknowledged their failure in one of the missions claimed by colonization: to protect the splendid Indochinese heritage from the ravages of time and indigenous barbarity.

As for the show itself, it was also occasionally reconfigured to create an impression of authenticity. For example, for the performance that the Ballet agreed to give in 1922 at the Palais Garnier, the venue’s designer imagined a scenographic framework intended to make the show more authentic. He designed a rather busy lighting set, with sylvan motifs which are not found in the Cambodian choreographic tradition. The quest for authenticity in exotic shows stemmed from an “imperialist nostalgia,” that particular form of nostalgia engendered by colonialism and which consists of regretting the disappearance of what was destroyed or transformed by the colonizing work, thus masking the sometimes brutal relations of domination that it implies.] [p 159 – 60]

[1] Anne Decoret-Ahiha, “L’exotique, l’ethnique et l’authentique: Regards et discours sur les danses d’ailleurs”, Civilisations 53÷1−2 (Musiques “populaires”), 2005: 149 – 66. See also by the same author Les Danses exotiques en France : 1880 – 1940, Paris : Centre national de la Danse, 2004.

12 years later, in Miomandre’s “Danse” book.

Miomandre’s 1923 demonstration was solidly argumented. However, more than a decade later, in his richly illustrated Danse (1935), the ravished “musings on the Cambodian dancers” of yore had given way to a more guarded, even disenchanted approach to Khmer dancing. To the seasoned dance critic, their body language now seems too aloof, their costumes and make-up too heavy, and the comparison with the fluid, almost jaunty Balinese dance comes at their disadvantage. Which leads to a three-fold question: had the miraculous Cambodian “child-priestesses” been just another Paris fad? was the Khmer dance intrinsically just impossible to be made “exotic,” thus banal? or did something happen to them? At that time, George Groslier himself — along with Cambodian mecenes of the ancestral art form, who then didn’t have their say on the matter — was worrying about the state of the Royal Ballet at the court of King Monivong.

Quoique ce [la danse indienne classique] soit assez obscur, on peut néanmoins suivre la ligne d’un ballet exécuté par les Soutradassi, mais ceux de leurs petites cousines cambodgiennes sont nettement inintelligibles, tout en développant les mêmes thèmes. Seulement l’extraordinaire beauté du spectacle emporte tout. Elles aussi sont entretenues par le souverain et forment une espèce de collège, où l’on reçoit une éducation des plus strictes, sous la surveillance d’une implacable et savante monitrice. Il né reste absolument plus rien de naturiste dans leur jeu. Rien, ni un clin d’oeil, ni un geste de la main n’est livré au hasard, à la fantaisie. Depuis leur entrée en scène jusqu’à la fin, tout ce qu’elles font a un sens : leur présence et leurs mouvements constituent un vivant hiéroglyphe.

Le costume roide d’orfroi dans lequel elles sont cousues, leur tiare, l’ondulation les ailerons de leurs épaules, de leurs bras étonnants de souplesse et qui semblent deux serpents vivants issus de leur buste, celle de leurs mains dont chaque doigt prolongé d’ongliers d’or a son existence personnelle, tout cela signifie une nuance de l’action, évoque un sentiment, une idée. Art tellement subtil, tellement raffiné qu’il est presque déshumanisé et qu’il né peut plaire qu’à des esprits savants et méditatifs, pour qui la chair n’existe plus, pour qui l’amour n’est qu’un prétexte à des rêveries de plus en plus abstraites et symboliques.

Les danseurs javanais,comme aussi ceux de Ceylan, sont beaucoup plus près de nous. L’Exposition coloniale nous a révélé ceux de Bâli, dont l’enchantement n’est pas près de quitter nos mémoires. Aussi somptueux au point de vue décoratif, leurs costumes ont beaucoup moins de rigidité. Ils permettent un jeu de mouvements plus variés, plus rapides et surtout plus riches en significations émotives. Ils né sont qu’une écorce splendide sur ces corps minces et souples, pleins de je né sais quelle grâce végétale, absolument saisissante. Et le répertoire est tellement plus varié ! Il comprend des scènes religieuses, mais aussi des épisodes de la vie courante, il admet la satire, la bonne humeur, toutes sortes de sentiments familiers, bref tous les aspects de l’existence d’une communauté humaine ingénue et primitive, mais sans que jamais on puisse oublier la présence imminente, écrasante, de la forêt vierge hantée de monstres et d’esprits de toutes les sortes. Ceux qui ont eu la chance d’assister à ces repré sentations dans leur décor d’origine, devant le palais d’un prince indigène, dans un jardin débordant de la formidable végétation tropicale ou dans une salle de réception, dont les fresques sont peuplées de dieux aux visages convulsés, effrayants et magnifiques, ceux-là prétendent que le spectacle, ainsi complet et dans son atmosphère, produit une impression inoubliable et grandiose. Néanmoins, telle est sa force de suggestion que, même privé de ce décor naturel, il en garde l’essentiel. La savante subtilité de la musique, l’extraordinaire beauté des éclairages et des accessoires, le sentiment de féerie qui baigne ces mimodrames éblouissants et naïfs, tout cela concourt à faire des danses de Bâli un des trois ou quatre plus parfaits spectacles chorégraphiques qu’il soit possible de voir sur la planète.[p 45 – 6]

[Although this one [the classical Indian dance] is rather obscure, one can nevertheless follow the lines of a ballet performed by the Soutradassi. Those of their little Cambodian cousins, one the other hand,are definitely unintelligible, even though they develop the same themes. Only the extraordinary beauty of the performance carries the day. They too are supported by the sovereign and form a kind of college where they receive the strictest education, under the supervision of an implacable and learned instructor. There is absolutely nothing natural left in their performance. Not a wink, not a gesture of the hand is left to chance, to fantasy. From their entrance on stage until the end, everything they do has meaning: their presence and their movements constitute a living hieroglyph.

The stiff orfray [ADB: decorative band] costume in which they are sewn, their tiara, the undulation of the fins on their shoulders, their astonishingly supple arms that resemble two living serpents emerging from their torsos, the undulation of their hands, each finger extended by golden nails with its own individual existence — all this signifies a nuance of action, evokes a feeling, an idea. An art so subtle, so refined that it is almost dehumanized and can only appeal to learned and meditative minds, for whom the flesh no longer exists, for whom love is only a pretext for increasingly abstract and symbolic reveries.

The Javanese dancers, like those of Ceylon, are much closer to us. The Colonial Exhibition [ADB: Paris 1931] revealed to us those of Bali, whose enchantment is not about to leave our memories. As sumptuous from a decorative point of view, their costumes are much less rigid. They allow for a more varied, faster, and above all, richer set of movements in emotional meaning. They are only a splendid bark on these thin and supple bodies, full of I don’t know what vegetal grace, absolutely striking. And the repertoire is so much more varied! It includes religious scenes, but also episodes from everyday life, it admits satire, good humor, all sorts of familiar feelings, in short all the aspects of the existence of an ingenuous and primitive human community, but without ever being able to forget the imminent, overwhelming presence of the virgin forest haunted by monsters and spirits of all kinds. Those who have had the good fortune to witness these performances in their original setting, in front of the palace of a native prince, in a garden overflowing with formidable tropical vegetation or in a reception hall, whose frescoes are peopled with gods with convulsed, frightening and magnificent faces, claim that the spectacle, thus complete and in its atmosphere, produces an unforgettable and grandiose impression. Nevertheless, such is its power of suggestion that, even deprived of this natural setting, it retains its essence. The learned subtlety of the music, the extraordinary beauty of the lighting and accessories, the feeling of enchantment which bathes these dazzling and naïve mimodramas, all this contributes to making the dances of Bali one of the three or four most perfect choreographic spectacles that it is possible to see on the planet.[p 45 – 6]

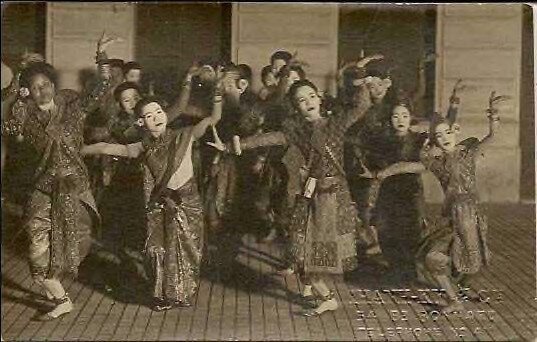

[Cambodian] Dancers, Paris Colonial Exhibition 1931. In the corner is the embossed caption “Khanh Ky et Cie, 54 Bd Bonnard Telephone No. 410.” [source: published by editor and translator Ellen Takata in “Photography in Vietnam from the End of the Nineteenth Century to the Start of the Twentieth, by Nguyễn Ðức Hiệp”, Trans Asia Photography 4 – 2, Spring 2014.]

This rare photography of Cambodian Royal Ballet dancers taken by a Vietnamese photographer is the the work Nguyễn Đình Khánh, styled Khánh Ký (1884 – 1946), whose studio on Hàng Da Street, Hanoi, became in 1893 the second photo studio ever owned by a Vietnamese after the photographic firm Đặng Huy Trứ was established on Thanh Hà Street in 1869.

After opening studios with students ‑from his same home village of Lai Xáin — in Nam Định (1905), Saigon (1907), Toulouse (1910, when first settled in France), he was active in Saigon from 1924 to 1933, with his main Saigon office at 54 Bonnard Avenue (now Lệ Lợi)., and a staff of 27 photographers, developers, retouchers, and salespeople.

Official portraitist of the French governors general in Indochina since 1917 — also portraying Vietnamese emperor Bảo Đại and the kings of Cambodia and Laos -, he worked for the Société des Etudes Indochinoises (Society for Indochinese Studies), and covered the 1931 Paris Exposition Coloniale for the periodical Monde colonial illustré (Colonial World Illustrated). () (1931) and the special issue for the 1931 Colonial Exposition (Exposition colonial 1931), as well as the 1932 issue, after Minister of Colonies Paul Reynaud made a state visit to Indochina.

In 1932, he went to Japan, made contact with early members of the Eastern Travel Movement, and was arrested by the French police upon his return for suspected nationalist inclinations. When his establishments went bankrupt, Khánh Ký returned to France in 1934, pursuing his photographic business and passing away in 1946. That same year, when Hồ Chí attended the Fontainebleau conference, he paid respects at the tomb of Khánh Ký, who had helped him in his struggling years as a Vietnamese student in Paris. [from Nguyễn Ðức Hiệp’s research translated and enriched by Ellen Takata]

Tags: dance, Royal Ballet of Cambodia, 1920s, Paris in the 1920s, exotic dance, Khmer dance, King Sisowath, King Monivong, 1930s

About the Author

Francis Miomandre (de)

Francis de Miomandre [born Francis Durand, penname taken from his mother’s name Thérèse de Miomandre] (22 May 1880, Tours — 1 Aug 1959, Saint-Brieuc, France) was a prolific writer, novelist, noted translator from Spanish, and art critic.

A precocious writer, he co-founded with a group of friends the Revue Méditerranéenne in 1894, when he was a teenager, and writing in the review L’Art et les artistes until 1912. As a novelist, he won the Prix Goncourt (1908) for Écrit sur l’eau…, while starting for decades to extensively translate Spanish authors such as José, Luis de Góngora, Miguel de Unamuno, Ventura Garcia Calderon, Miguel de Cervantes, Miguel Angel Asturias, Lydia Cabrera, Horacio Quiroga, Benito Perez Galdos, Enrique Rodríguez Larreta, Lazcano Tags, Eugenio d’Ors, Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis, Jose Martí.

With a clear, fluid style, he contributed numerous art critic reviews and essays, including writings on Cambodian dancers he’ve seen performing in France. India and Asia are a recuring theme in his fiction and critic writings. Spanning near six decades, Miomandre published around 60 novels and 50 translations, some feat for a writer who, commenting on Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Fur, mocked in 1908 la “vanité du métier d’écrire” [the vanity of the writing trade] (“Lettres à Juliette (extraits),” posthumously published in 1974, p.

Publications

- Les Reflets et les souvenirs [poems], Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Occident, 1904.

- “Claudel et Suarès” [conference], Bruxelles, La Libre esthétique, 1907.

- Visages, Bruges, Herbert, 1907.

- Écrit sur de l’eau…, Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1908; repr.: Paris, Ferenczi, coll. Le Livre moderne illustré 1, 1923; repr. Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1947; repr. Monaco, Les Éditions nationales de Monaco, 1950; Paris, La Différence, 2013.

- Aventures merveilleuses d’Yvan Danubsko, prince valaque, Paris, Daragon, 1909.

- Le Vent et la Poussière, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1909

Au Bön Soleil, scènes de la vie provençale, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1911. - Digression peacockienne, Paris, Champion, 1911.

- Gazelle (Mémoire d’une tortue), Paris, Dorbon, 1910.

- L’Ingénu, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1911.

- Figures d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, Paris, Dorbon-Ainé, 1911.

- [‘roman pour les enfants’] Histoire de Pierre Pons, pantin de feutre, Paris, Fayard, 1912 ; repr. Paris, Les Arts et le livre, 1927; ENG The Story of Pierre Pons, New York, 1929.

- … D’amour et d’eau fraîche, Paris, Payot. 1913.

- L’Aventure de Thérèse Beauchamps, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1913 ; repr.. Paris, Arthème Fayard, 1925.

- “Méditation sur la femme de France”, Paris, Nouvel Essor, 1916.

- Le Veau d’or et la vache enragée, Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1917.

- Pantomime anglaise, Paris, Renaissance du livre, 1918.

- Voyages d’un sédentaire. Fantaisies, Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1918.

- La Cabane d’amour ou le Retour de l’oncle Arsène, Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1919. | script for La Cabane d’amour, movie by Jeanne Bruno-Ruby (1923).

- Le Mariage de Geneviève, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1920.

- L’Amour sous les oliviers, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1921.

- Le Pavillon du Mandarin [art critic pieces] Paris, Émile-Paul, 1921.

- Dans le goût vénitien, Paris, 1921.

- Les Taupes, Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1922.

- Ces petits messieurs, Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1922 ; repr. Paris, Les Éditions de France, 1933.

- “Rêveries sur les danseuses cambodgiennes”, Danse, Nov. 1923.

- Le Greluchon sentimental, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1923; repr. Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1938.

- La Naufragée, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1924; ibid.,1928.

- La Jeune Fille au jardin, Paris, Ferenczi & Fils, 1924.

- Contes des cloches de cristal, Paris, Chez Madame Lesage, 1925.

- Éloge de la laideur. Paris, Hachette, 1925 ; repr. Paris, Les Éditions Cartouche, 2010. ISBN 9782915842685.

- La Bonbonnière d’or, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1925.

- Fumets et fumées. L’art de manger, l’art de boire, l’art de fumer, Paris, Le Divan, 1925.

- L’Ombré et l’Amour. Journal d’un homme timide, Paris, Vald. Rasmussen, 1925.

- La Mode, Paris, Hachette, 1926.

- Le Radjah de Mazulipatam, Paris, Ferenczi & fils, 1926; repub. Kailash, 1996.

- L’Amour de Mademoiselle Duverrier, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1926; ibid., 1932.

- Olympe et ses amis. Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1927 ; repr. ibid., 1937.

- Bestiaire [illus. by Simon Bussy], Paris, Govone, 1927.

- Passy-Auteuil ou Le vieux monsieur du square. Monologue intérieur, Paris, André Delpeuch éditeur, 1928.

- Les Baladins d’amour, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1928 ; repr. ibid., 1934.

- Le Casino, Paris, Nouvelle Société d’Édition, 1928.

- Grasse, Paris, Émile-Paul Frères, 1928.

- La Vie amoureuse de Vénus, déesse de l’amour, Paris, Ernest Flammarion, 1929.

- Soleil de Grasse, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1929.

- Le Jeune Homme des palaces, Paris, Éditions des Portiques, 1929.

- Baroque, Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1929 ; repr. ibid., 1935.

- Le Patriarche, nouvelle, Paris, Aux dépens de la Société de la gravure, 1929.

- Vie du sage Prospero, Paris, Plon, 1930.

- Jeux de glaces, Roman. Paris, Ferenczi et Fils, 1930.

- Foujita, Paris, L’Art et les artistes special issue, 1931.

- Âmes russes 1910, Paris, J. Ferenczi & Fils, 1931.

- Samsara [poems], Paris, Éditions Fourcade,1931.

- Les Égarements de Blandine, Paris, Editions Ferenczi, 1932; repr. id., 1936.

- Dancings, Paris, Flammarion, 1932.

- Otarie: arabesque amoureuse et marine [poems, dedicated to Blaise Cendrars], Paris, Maurice d’Hartoy, 1933.

- Danse, Paris, Flammarion, 1935.

- Le Zombie, Paris, Ferenczi, 1935.

- Le Cabinet chinois, Paris, Gallimard, 1936.

- Direction Étoile, Paris, Plon, 1937; repr. with preface by Bernard Quiriny, illustrations by Régis Lejonc, Talence, L’Arbre vengeur, 2021.

- L’Invasion du paradis, Paris, Ferenczi, 1937.

- Mon Caméléon, Paris, Albin Michel, 1937 ; repr. with preface and bibliography by Éric Dussert, Talence, L’Arbre vengeur, , 256 p. ISBN : 979−10−91504−56−0.

- Le Fil d’Ariane, Avignon, Édouard Aubanel éditeur, 1941.

- Portes [short stories], Neuchâtel, Éditions de la Baconnière, Nov. 1943.

- Fugues, Marseille, Robert Laffont, 1943.

- Les Jardins de Marguilène, Fribourg, L.U.F., 1943.

- Le Raton laveur et le maître d’hôtel, Fribourg, L.U.F., 1944.

- Primevère et l’Ange, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1945.

- L’Âne de Buridan, Lyon, Éditions Ludunum, 1946.

- La Conférence, Paris, Le Bateau ivre, 1946.

- Mallarmé, Mulhouse, Bader-Dufour, 1948.

- Rencontres dans la nuit, Bienne, Éditions du Panorama/Éditions du Dauphin, 1954.

- L’Œuf de Colomb, Paris, Grasset, 1954.

- Aorasie, Paris, Grasset, 1957.

- Caprices [short stories], Paris, Gallimard, 1960.

- “Lettres à Juliette (extraits)”, unpublished text pr. in Littératures 21, Annales publiées par l’Université de Toulouse, 1974 : 131 – 148.

- translations from Spanish not listed here.

- A collection of Francis de Miomandre’s writings (1931−1939): LUX: Yale University Collections.