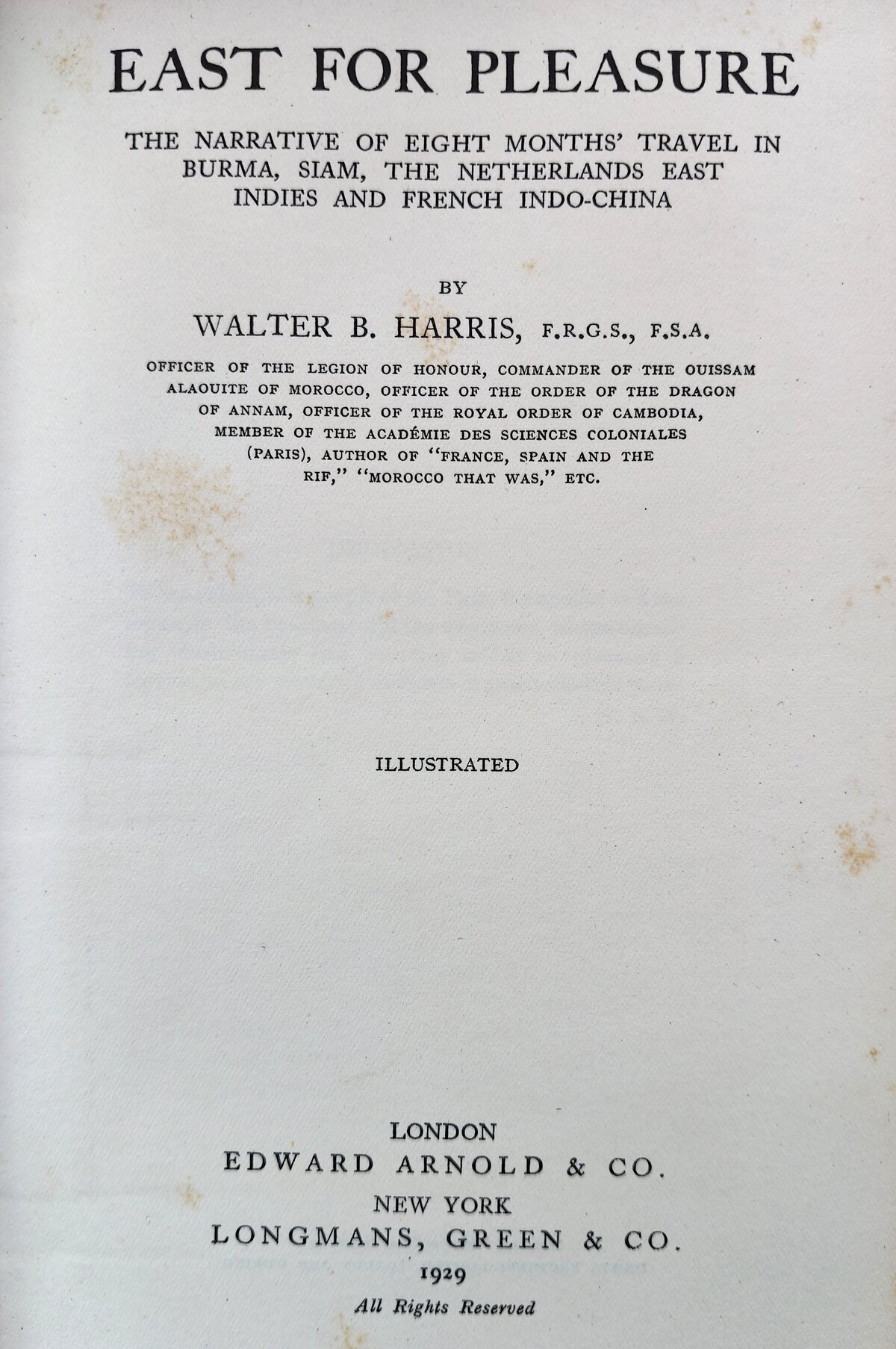

East for Pleasure: The Narrative of Eight Months' Travel in Burma, Sian, the Netherlands East Indies and French Indo-China

by Walter B. Harris

A clever depiction of Asia in 1928 through a leisure travelogue including Angkor Wat and the ceremonies for the coronation of HM King Monivong.

- Format

- hardback

- Publisher

- London: Edward Arnold & Co. | New York: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Published

- 1929

- Author

- Walter B. Harris

- Pages

- 399

- Language

- English

This was the time brilliant Western writers and photographers flocked to Southeast Asia, particularly eager to see ‘Angkor the Magnificent’, to quote American reporter Helen Churchill Candee’s famous book (1924). Part of the ‘Asian grand tour’ or heading specifically to Cambodia, they’d stop at Phnom Penh to see the Royal Palace and get an in-depth briefing from George Groslier, head to Angkor on the new ‘colonial road’, stay at Bungalow d’Angkor, write more or less inspired pages about the Khmer ruins, motor back to Saigon and sail away. Harriett Ponder, Martin Hürlimann, Helen Churchill again (for New Journeys in Old Asia, 1927), Grace Thompson-Seton, larger-than life Chicago journalist Bob Casey, Geoffrey Gorer and his psychoanalytic ‘pleasure trip’ from Bali to Angkor, and the present book, ‘pleasure trip’ not being an early version of sexual tourism but just the English way to refer to ‘vacation’.

Another noted journalist, Walter B. Harris was well into his fifties when, “tired of the cruelties of war” (in Morocco), he journeyed through Southeast Asia, “not for work” but still with all travel expenses covered by his former newspaper, The London Times. Far from the daredevil rookie journalist who had lived amongst the Berber rebels and criticized French expansionism in North Africa, he was now a debonair man of the world, and a decided Francophile. While the American writers were blaming the excesses of French rule over ‘Indochina’, he broke bread with the top colonial administrators in Saigon, and this was how he came to ‘cover’ King Monivong’s coronation in July 1928:

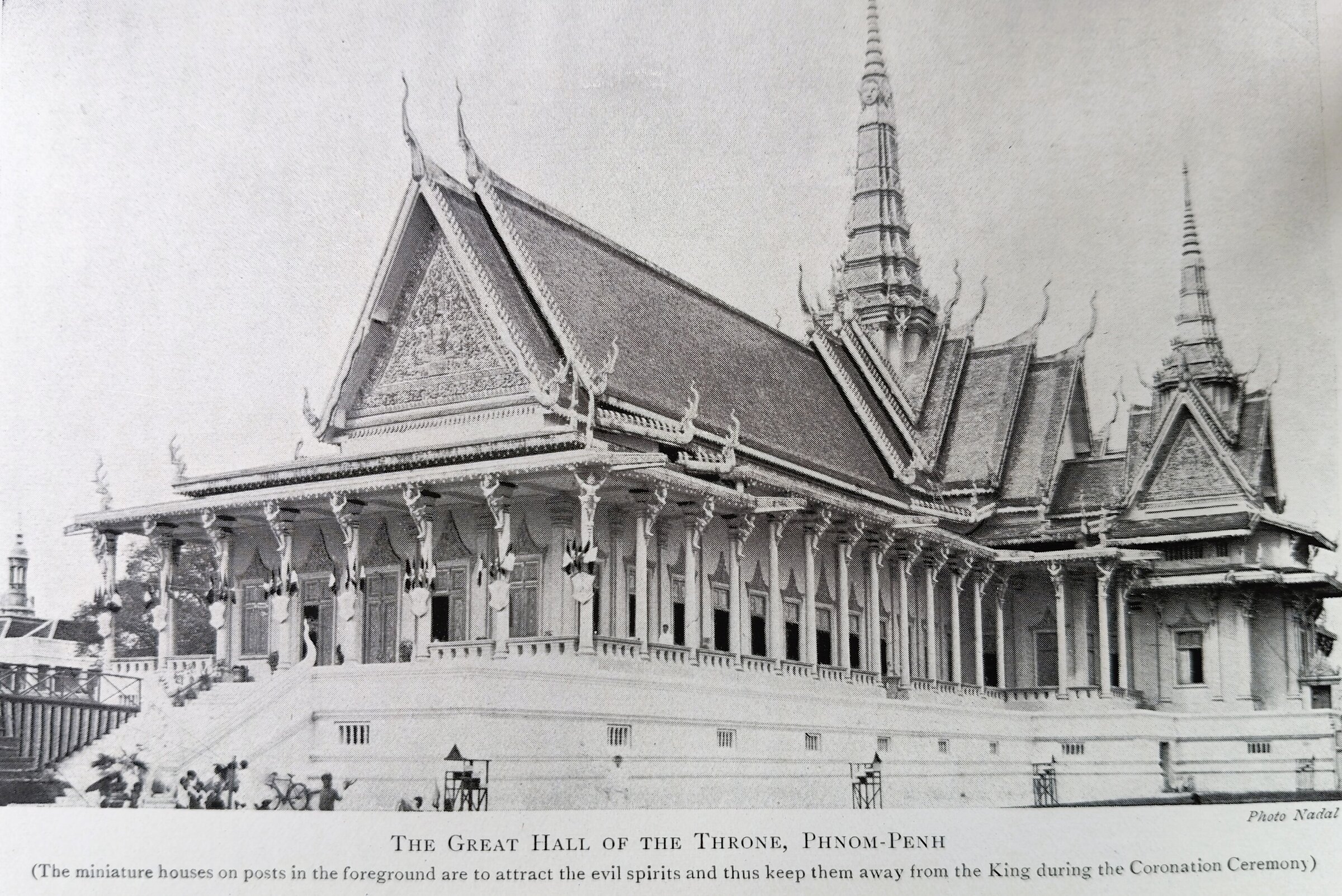

The Throne Hall shortly before King Monivong’s coronation ceremonies, July 1928 [photo by Nadal reproduced in the book].

The steamer on which I travelled was the Cap Lay, a large and very comfortable French boat. It was my intention to visit the North of Indo-China, and to descend Southward by the old Mandarin road through Annam and Cochin-China, and on into Cambodia. The fact that the Cap Lay was to spend three days in Saigon would give me ample time to obtain information and to prepare my plans. But I had counted without taking into account the kindness, hospitality, and assistance I was to receive from the French authorities in Saigon — a welcome that recalled my pleasant relations with the representatives of France in many lands. My three days’ visit to Saigon, which was reached after a calm passage of about 60 hours from Singapore, was not only one of much pleasure, but one of extreme interest. At the table of the Governor of Cochin-China — Monsieur Blanchard de la Brosse — I met daily a succession of the people whom he considered it would interest me to talk with officials and archæologists, artists and politicians. Those luncheons and dinners, in surroundings of infinite taste and artistic refinement, were rendered still more attractive by the presence of French ladies who brought not only their charm and their dresses from Paris, but also those intellectual qualities which render intelligent French-women such brilliant and delightful conversationalists. But this was not the only service that Monsieur Blanchard de la Brosse rendered me. He persuaded me to abandon my passage on the Cap Lay to Haiphong, urging me, ably seconded by Monsieur le Fol, the Résident-Supérieur in Cambodia, to visit Angkor and Phnom-Penh before going North, so as to be present at the coronation of the King of Cambodia on July 22nd. [p 283]

And while American travelers expressed their shock at the blatant humiliation of the “natives”, the wealthy Briton found the French system lacking of segregationism:

The shops of the Rue Catinat recall those of Paris, and Saigon must be rich to be able to afford the jewels which many of the windows display with that taste which is so essentially French. The extravagance of Europe has travelled far, and I was told, by those who know, that there are to-day dressmakers in Saigon as efficient and almost as expensive as those of the Rue de la Paix. […] As elsewhere in these Eastern lands the advisability of segregation was recognized too late, and between the wide avenues and principal streets of Saigon there are many small, congested districts, which cannot but prove injurious to the public health. The majority of the native population, however, that is to say a hundred thousand Annamites and Chinese, inhabit the town of Cholon, situated three miles away, as typical a modern Chinese city as is to be met with in the Celestial Republic itself. [p 285]

Saigon, it must be said, was the umpteenth port-of-call in Harris’ grand and leisurely tour, as he had already visited Burma, Siam, Maritime Southeast Asia from Java and the Moluccas to Bali [see below], but it’s in opting for the long (two nights and one day) boat trip to Phnom Penh he had the first opportunity to get closer to the local “gentlefolk”, and his observations showed a real empathy. First, the human landscape of the riverbanks, first:

All the rivers of South-East Asia in their lower courses and deltas resemble one another-wide, yellow expanses of water, flowing through flat country. The Mekong might be the Menam of Siam, or even the delta of the Irrawaddy of Burma, so alike they are. The banks are low, covered with a dense growth of Nipa palms or jungle wherever they have not been cleared for the cultivation of rice. On the lower reaches, in the province of Cochin-China where the Annamite has migrated from the North, there is much cultivation, but as the confines of Cambodia are reached the jungle predominates and the decadence of the once great race of the the Khmers the Cambodian of to-day-becomes apparent. Diminished in numbers, the victims of centuries of outside attack and internal decline, these sympathetic people are gradually disappearing. In time there will be few or no traces of them left, except those ruins of their early magnificence, the mighty edifices of Angkor. [p 282].

Hollywood irrupts on the river boat to Phnom Penh

While observing the life on the third-class deck, the author was reminded of a particular feature movie that has been released a few months before his trip:

They all ate decorously and slowly, accompanying their meals with much conversation. Their manners were natural and pleasant. In nothing is race and breeding better demonstrated than in the manner of eating, and the Annamites seem to stand high in this respect. It is seldom a pleasure to see people feed, yet as I sat on deck and watched these simple folk partake of their meat and drink their tea, I felt instinctively that a long period of civilization lay behind them. It is so, of course; their lineage goes back for many centuries a past of war and cruelty, of art and scholarship, of evil tradition and refinement a race of gentlefolk in their own way, which is not, of course, always ours. The women, when their mouths are not disfigured by the unpardonable habit of chewing betel-nut, are attractive. Like their female cousins, the Chinese women, they leave nature unadorned by artifice, and sink into maturity and age with dignity and apparently with indifference. In their costume, as in the manner of dressing their hair, there is no variety. Sometimes the long tunic is brown instead of black, and much more rarely still, violet. The hair is parted over the forehead, and drawn back demurely to right and left. Across the crown of the head is a wide plait, a natural “bandeau”. The result is very attractive, and gives a charming finish to the well-shaped face and delicate features.

The children were discreetly inquisitive, but timid. It took a long time before I could persuade a little girl of seven or eight years of age, in tight, dark blue trousers, and a light green sash and nothing else, to venture to look through my field-glasses. At length she screwed up her courage, and made a close inspection of the shore. The ordeal over she ran off, proud of her audacity, and collecting the other children round her she narrated what she had seen. Her little almond eyes widened as she told her voluble story. She was terribly serious, and the others sat around and listened, holding their breath — but in spite of my renewed invitation neither she nor any of the others would venture again. I think she must have frightened them with her account of her experience, and perhaps even frightened herself. I feel certain that she said that she had perceived elephants and tigers and evil spirits peering at her from the jungle on the shore. I hope she had. I like to feel that my field-glasses, companions of so many years of travel, had shown her something that no one else could see, even if it was only the reflex of her own imagination. Her reputation for adventurous courage was very apparent. Her little companions hung upon the words of her lips, and her manner changed; she had acquired a position.

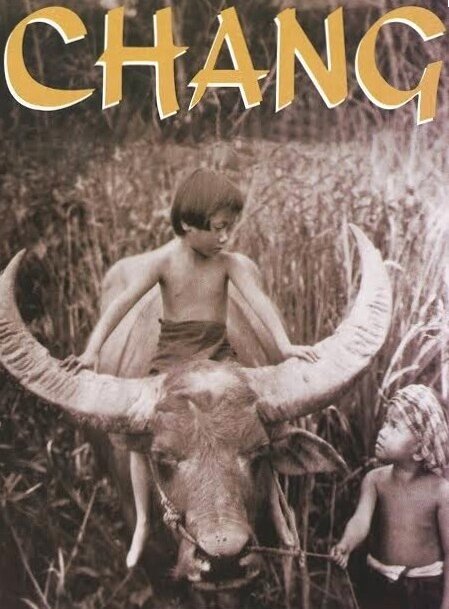

I was told in Siam that the little girl who played with such remarkable charm and ability the part of the child in that most delightful of films “Chang”, when she was told that her portrait and her acting had been so popular that hundreds and thousands of people had been to see the picture, suddenly and spontaneously adopted the attitude and the outlook of the full-blown professional cinema star. She demanded, and obtained, recognition of a state of superiority far above and beyond her little companions. Happily her surroundings have limited the extent of her attitude toward the rest of the world, and she is said to remain comparatively unspoiled. But her position is undisputed amongst the children of her native place. She is the Mary Pickford of North Siam and lives up to it. [stage name of Gladys Louise Smith (1892 – 1979), a Canadian-America movie star]. known professionally as Mary Pickford, was a Canadian American film actress and producerof North Siam, [p 294 – 295]

1) ‘At the Temple Gate in Bali’ [photo by Kurkdjian, used as frontispiece]. 2) The poster of the film Chang, released in April 1927.

Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, also known simply as Chang [from th ช้าง or lao ຊ້າງ, “elephant”] was an American silent ‘documentary’ film that became a watershed in the history of Hollywood, first because its audacious shooting in the Lao-Thai jungle was to inspire the co-directors Merian C. Cooper (1893 – 1973) and Ernest B. Schoedsack (1893 – 1979) for their 1933 blockbuster King Kong, and second because it has been seen as the first case of ‘animal exploitation’ in a Hollywoodian production. As Shari Kizirian noted for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival 2009, “Cooper and Schoedsack had Flaherty in mind when they set out for Siam’s remote jungles, staying more than one year among the Lao of Nan Province. They assembled a fictional family [ADB: the little girl’s character was named Chantui, her brother Nah, and their pet gibbon Bimbo]. They built a solitary house in the jungle to manufacture a drama that no Lao would actually risk, life away from other villagers. They also manufactured close-action situations with tigers and elephants to thrill audiences back home.”

The coronation of King Sisowath Monivong

Back to Phnom Penh, of which the author gave a quite detailed description, complete with the Wat Phnom zoo and the recently inaugurated museum:

Phnom Penh from time to time has been besieged, conquered, sacked, and deserted. Other capitals sprang up, and in their turn were abandoned, and it is only about 60 years ago that the town was once more selected as the capital and became again, after a long period of desertion, the residence of the King. A new town has sprung up. The palace was rebuilt, the temples restored. European quarters were laid out stretching along the river banks. Cambodia became a French Protectorate, being unable alone to withstand the encroachments of the Siamese and the Annamites. Siam restored the outlying provinces that she had taken from the Cambodians, and to-day the country is complete. But it is too late, the Cambodian has lost his virility and his enterprise. The population is decreasing. The Annamite, more energetic and an agriculturist, is taking up the land. Cambodia and its dynasty will remain, for France is behind them, but the descendants of the great and artistic race of the Khmers will die out. It is a pity. They are a rather heavy, dull, idle people, spending their time sitting by the roadside, cultivating when cultivation is necessary, but seemingly exerting no energy of any kind that can possibly be avoided. They are gamblers, and as far as their small means permit, spendthrifts, a pleasant, but rather useless race.

Like all the towns which the French have planned and laid out in Indo-China, Phnom-Penh has its good features. The streets are shaded by beautiful trees, there are public gardens and open spaces. In the centre of the European quarter is the Phnom crowned by its Wat (temple) with its roof of iridescent tiles, its tall gilded spire and its portico of columns. Flights of monumental steps lead up the hill, amidst grassy lawns and flowering shrubs. Round the base stand pagodas in the Cambodian style, domes rising to a spire. At the foot of the stairway great stone lions carved in Chinese style sit and grin. The climate — hot and wet-renders the surrounding gardens a mass of luxuriant greenery.

Amongst the groves of trees are cages and enclosures, containing a modest collection of the beasts and birds of the country — tigers, leopards, monkeys, deer, and wild boar; crocodiles and serpents, and aviaries full of birds, principally waders and waterfowl. These animals seem to be the delight of the Cambodian children, hundreds of whom had come, at the time of my visit to Phnom-Penh, with their parents for the coronation of their King. They stood open-eyed and open-mouthed in front of the cages, lost in admiration and wonderment. Everywhere the streets teemed with life, for the occasion had been declared a public holiday, and ox-wagons, motor buses, hired cars, steamers and native boats had brought together the greatest crowd Phnom-Penh had ever known. The town was bright with flags and masts and streamers, with arches and paper lanterns; with gaily decked tribunes and gaily dressed people.

[…] At the Southern extremity of the town, separated from the river by an open green space and a wide avenue, stands the King’s palace in a square, walled enclosure, over 1,000 yards in each direction. From without little is visible except the fantastic roofs of brilliant yellow tiles, capped with their spires and twisted, projecting eaves. One of these buildings, wall-less and with a roof supported on columns, stands on the palace wall overlooking the avenue. It is there that the King and his Court congregate to watch the reviews of his troops or the public fetes held on the open space.

In this quarter of the town close to the palace is the National Museum, a treasure house of art and antiquity. The building itself is in the Khmer style, with superimposed roofs, a tapering spire, and upturned eaves. The windows and doors are all reproductions of the antique. The result is most happy a building worthy of its contents. The portico, which extends the full length of the construction, is reached by a wide flight of steps, and contains specimens of sculptured stone statues and decorative panels. Within, in the central hall, is a collection of treasures from the royal palace, gold cups and trays, some of them decorated in enamel, ewers, jewellery worn by the famous palace dancers, daggers and swords, while on the walls and pillars are exhibited “Sampots”- the long garment of woven and brocaded silk worn as a skirt. These delightful examples of native weaving are some of them of great beauty in texture, design, and colour. Galleries lead to right and left, containing Buddhist and Hindu statuary, bronze objects and images, and representations of the Hindu gods, some of them unique examples of ancient Khmer art. One or two of the statues of stone are of very fine quality. Greek influence is apparent in the pose and drapery of more than one. Amongst the statues Buddha and the Hindu divinities, Vishna and Siva, predominate. At the end of the gallery there is a comprehensive collection representing Cambodian life articles of carved wood and lacquer, some decorative paintings, theatrical masks, dresses of the famous palace ballet, musical instruments, and other objects. Phnom-Penh may well be proud of its museum.

[…] At the time of my visit there was a great influx of visitors for the Coronation, and the cafés were full. In the street alongside passes a panorama of the Far East-Annamites and Cambodians, Chinese and Europeans, jinrickshas and motor-cars, pedlars and soldiers. Beyond the wide road the river flows, broad, silent, and dotted with boats. The Annamite waiters move quickly amongst the tables. There is a constant ripple of pleasant laughter from the seated groups, men and women. The worries of life, the heat of the day, are forgotten. The presence of ladies turns the conversation from politics and business into lighter channels. It is a little corner of Paris. There is no untidiness, no slackness either in manners, or dress or language. The officers in white uniforms, the townspeople in starched white suits, the wives and sisters and daughters suitably and becomingly arrayed. The drinks are the apéritifs beloved of the Frenchman, Vermouth, a Pernod perhaps, and here and there a cocktail. The women drink syrups and lemon squashes. The scene is typically French, amusing, discreet, and sober. There is no noise, no loud shouting for the waiters, no interminable whiskeys and sodas, no bar, no jazz, no glow of too ruddy countenances, and no unsteady feet when the parties break up. [p 303 – 6].

And then it was time for the author to depict the coronation ceremonies, which he did with more attention to details than his French colleague Alfred Meynard, who was covering the event for the Revue indochinoise [RI-Extreme Asie, 29 Oct. 1928]:

When I reached Phnom-Penh, as the guest of the French Protectorate Government, on July 21, 1928, preparations on a grand scale had already been made for the coming Coronation, and the final touches were being given to the decoration of the streets and of the Palace. Flags were flying everywhere, tall masts adorned the roadways, and triumphal arches. In the Palace enclosure itself everything sparkled and glittered. The “Great Hall of the Throne”, the “Hall of Festivals”, and the “Silver Pagoda”, with their white colonnades, their iridescent superimposed roofs, their upturned eaves ending in long gilded points, their walls of gold and looking-glass and their tapering spires, formed a fitting background for the crowning of an Oriental Monarch.

What crowds flocked the streets and the Palace lawns! Men, women, and children from all over the country, in their hundreds and their thousands, wandered about leisurely, a little untidy, but quite evidently happy. What funny, fat, brown children stood gazing open-eyed and open-mouthed at the decorations. Most of them had never seen anything except their native villages of bamboo huts, built on high piles. How all this must have astonished and dazzled them! What stories they must have told to their less fortunate little companions on their return to their homes!

About the Palace grounds were erected gaily painted model houses, a foot or more square, perched on poles a yard or more high, in which offerings of fruit and flowers were made to the evil spirits of earth and air in which every Cambodian so firmly believes. By tempting them into these attractive little shrines the ubiquitous, naughty devils were kept away from the royal abode and its inmates. The astrologers had decided that July 23rd was the propitious day for the Coronation, and at dawn the salutes of cannon and the strains of military bands announced that the ceremonies were about to begin. The French Governor-General of Indo-China, the Resident at the Court of Cambodia and the Governor of Cochin-China, with a large suite of military and naval officers, represented the French Republic. The King’s guests were shown on arrival onto the terrace of the “Great Hall of the Throne”, where were already collected a number of Cambodian dignitaries in the most gorgeous of raiment, silks and velvets and brocades of many colours, richly woven with silver thread or em-broidered with gold.

Punctually at seven o’clock the King, after having made offerings to the Buddha, appeared and passed by an extemporized bridge onto a nine-storied daïs, under the gilded, shrine-like canopy of which His Majesty stood, his feet isolated from the floor by a plaque of gold and a plaque of silver, resting upon the leaves of a sacred fig-tree. King Sisowath Monivong was draped in a white and yellow robe. Brahman priests were at his side, and the high officials of his Court surrounded him, each shaded by a gorgeous State parasol of the colour and size pertaining to his rank. The ceremony of bathing the King with “Lustral Water” brought from various holy places in the country and blessed, then followed. It began by the King receiving from the Chief Brahman priest a little branch of the “Cheypruc” tree, an emblem of supreme power and eternal prosperity. Each of the appointed authorities emptied a ewer of the sacred liquid over His Majesty, the first to do so being the French Governor-General. Eight Brahman priests, in white robes, broadly edged in gold, officiated, and at the close of the ceremony the Head of the Buddhist faith in Cambodia, an aged man dressed in the humble, yellow cotton garment of a monk, was led forward with tottering steps to bless the King.

Certain strictly religious functions connected with the domestic life of the Sovereign had preceded the State ceremony of the Coronation by several days. The King, through the Brahman priests attached to his Court — for although the State religion is Buddhism, the Brahmans still officiate on these occasions - had requested and had been granted the permission of the guardian angels of the Palace to inhabit the apartments reserved for the Sovereign; for, from the death of one King until the Coronation of the next, the successor is only Regent. A long time often elapses between these two events, for the astrologers have to decide not only on a propitious day for the Coronation, but also for an equally propitious one for the cremation of the body of the deceased monarch.

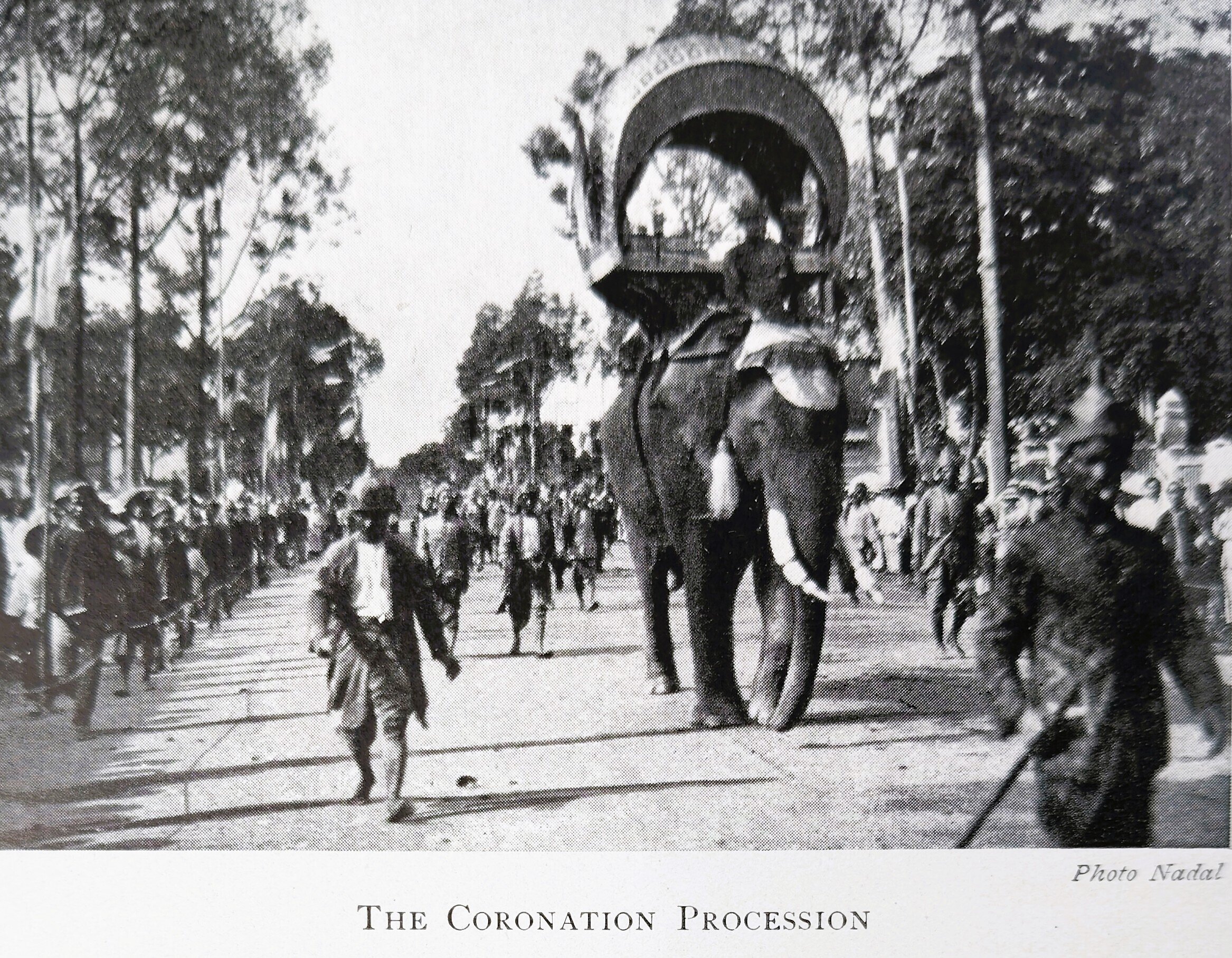

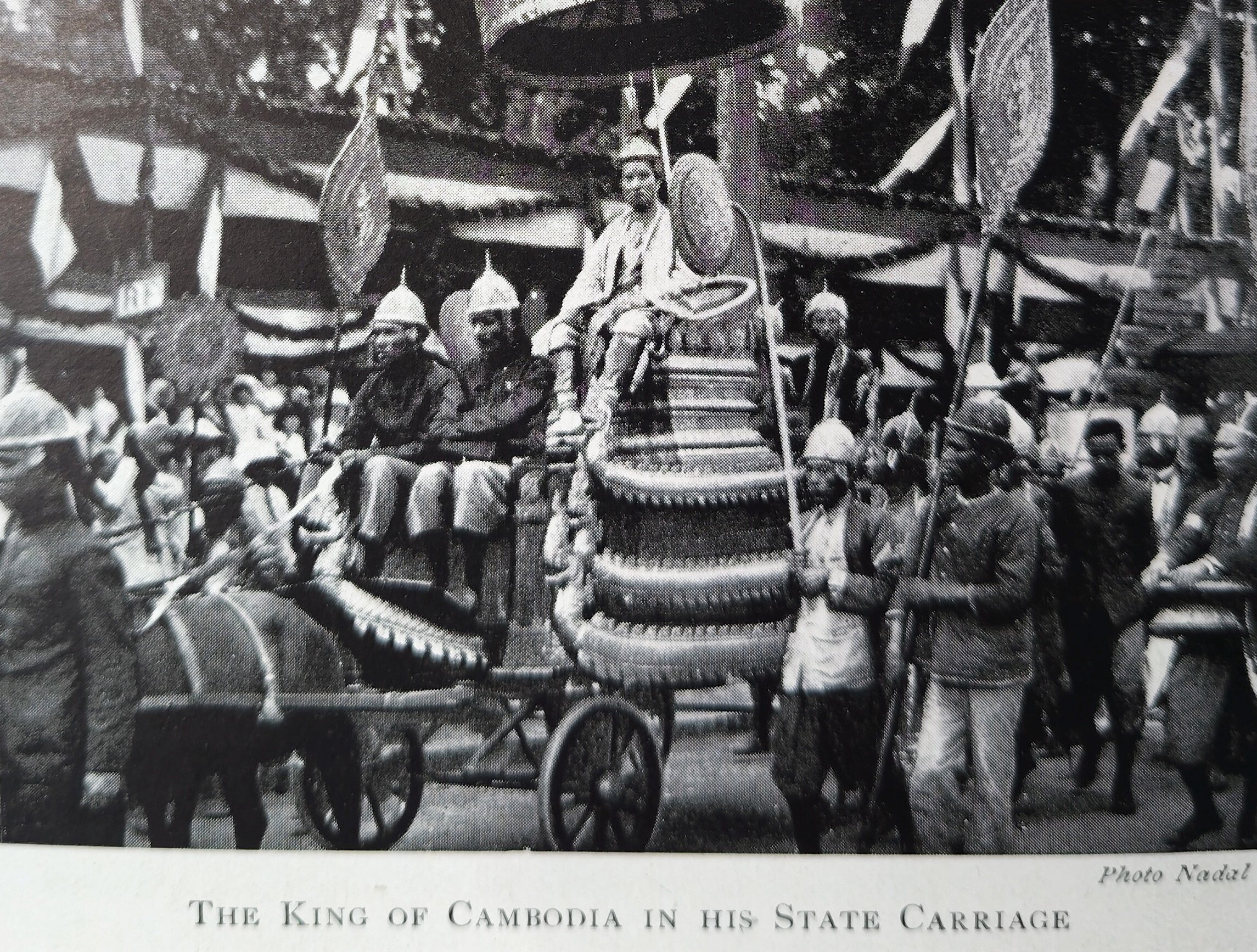

Two views of the town processions [photos by Nadal reproduced in the book.

While the King was receiving his “Lustral Bath”- emblematic of spiritual purification — there was a constant coming and going of gaily dressed Palace attendants and private servants, bearing to the “Throne Hall” the offerings of the people. These offerings varied little for they are purely ritual‑a tray of fruit and flowers with a very small cup of alcohol. Native music accompanied the ceremony‑a tinkling of pleasant metal instruments struck with little hammers and at the moment when the King rose to regain the Throne Hall a harsh blast was blown upon the sacred conches, the big shell instruments that have come down through many generations. Once more the great, flat parasols were opened to shade the monarch and his courtiers on their return procession. The King’s, the largest of all, was of gold and silver thread slightly shot with purple, with a deep fringe of the same beautiful material; the rest were of every hue. The scene was full of brilliancy with its crowd of Cambodian officials arrayed in rainbow colours and sparkling with gold.

The ceremony of the “Lustral Bath” terminated, the King retired into the precincts of his palace where, after his feet had been anointed with sacred oils, he donned his robes of State. An hour later the ceremony of His Majesty’s actual Coronation took place in “the Great Hall of the Throne”, a vast building the interior of which, a mixture of European and Oriental architecture-all gilt and colour-was eminently suited for so gorgeous a function. When the company were all assembled the King entered alone and, after making offerings to the Gods, took his seat on a gold chair on the left of the tall, tapering daïs on which, high up, was the throne. Directly above it, suspended from the roof, hung nine flat deeply fringed parasols of white silk one above the other, diminishing in size as they ascended, until the highest of all was of very modest dimensions. Around the open space before the daïs stood the High Officers and the members of the Court, all gorgeously arrayed. The King himself wore a State dress of orange gold brocade. The tunic, with a semblance of wings at the shoulders, was tight fitting, while the “sampot” ‑a skirt drawn forward between the legs and fastened in front at the waist reached almost to the ankles. His stockings were of orange silk, and his shoes with turned up toes sparkled with gold and silver thread. Beside him, on a similar gilt chair, sat another monarch of Indo-China, the King of Luang-Prabang, whose dominions lie inland to the North on the upper reaches of the Mekong river. He had made the long and by no means easy journey to be present at the Coronation. The “Great Hall” was filled with guests a fine mass of colour, the Europeans in white uniforms, and the Cambodians in dresses of every hue and and shade. Acting on tradition no ladies were present at any of these ceremonies, although female seclusion does not exist, and the women of Cambodia are allowed considerable freedom.

On the entry of the eight officiating Brahman priests the King rose and seated himself upon a low chair immediately in front of the throne daïs. The eight Brahmans approached and knelt around the Sovereign, representing the eight points of the compass. One after the other they repeated the traditional prayer for the King’s welfare, His Majesty turning his chair so as to face each priest as he spoke. During this part of the ceremony the King, although a Buddhist, held in his hand images of Vishnu and Siva, the “Protectors of Cambodia”, a tradition of the old Vedic faith so deeply rooted in the country. At the conclusion of the prayers of the “Bakous”, the Chief Brahman handed to the King a small cup of sacred water, which His Majesty drank. A high official then read a declaration by the terms of which the State of Cambodia, and everything in it, was recognized as the property of the Sovereign. Immediately this speech was over the Princes and ministers presented to the King the attributes and symbols and seals of their offices, which His Majesty graciously restored, confirming them in their posts.

At the invitation of the Governor-General the King mounted the steep steps of the throne daïs, to the singing of chants and the playing of music. Immediately he had taken his seat upon the throne the Governor-General of French Indo-China and the French Resident in Cambodia approached and joined him on the daïs. While the former placed the Crown upon the King’s head, the latter handed him the sacred sword, a treasured inheritance of the Sovereigns of Cambodia, a weapon of mythical origin. Its blade is never fully drawn except on a declaration of war. A blast of harsh notes from the sacred conches, a rattling of strange wooden instruments and a salute from the gun-boats away on the river announced to the gathering and to his subjects without that Sisowath Monivong was crowned King of Cambodia. The officials descended from the daïs, and in a blaze of light the Sovereign sat enthroned in his dazzling robe of State, high above the heads of the assembled company. It was a most imposing sight admirably staged.

When the moment came to descend the perilous steps of the daïs that supported the throne the King had to be assisted by his officers. The weight and discomfort of the tall pointed crown, the great heat and the thrill of the ceremony had overcome him, but his discomfiture was only of a few moments duration, and he took his place at the foot of the daïs to receive the congratulations of his guests. Even then his task was not over for in the privacy of the Palace another ceremony awaited him. The ladies of the Royal Family and of the Cambodian aristocracy and Court were waiting to offer their congratulations and to do obeisance.

That night His Majesty gave a State dinner-party in a great hall in the palace grounds. The heat at Phnom-Penh is so excessive that the State buildings constructed for entertaining have no walls. They consist of magnificently coloured and decorated roofs supported on rows of columns, the floors raised above the surrounding garden down to which flights of steps descend. Only the “Throne Hall” and the residences possess walls. It must be no easy task to serve a the private buildings in which the King and Royal Family State dinner for 170 persons in Phnom Penh, for the little capital is far removed from the outer world, and has no railway connection with anywhere. But the King’s entertainment was a remarkable success. The food was well cooked and well served. The dishes, with the exception of that rare delicacy birds’ nest soup, were prepared in European fashion. The china was a service of Limoges decorated with the Arms of Cambodia and of beautiful ancestors of the present Sovereign was really admirable in quality.

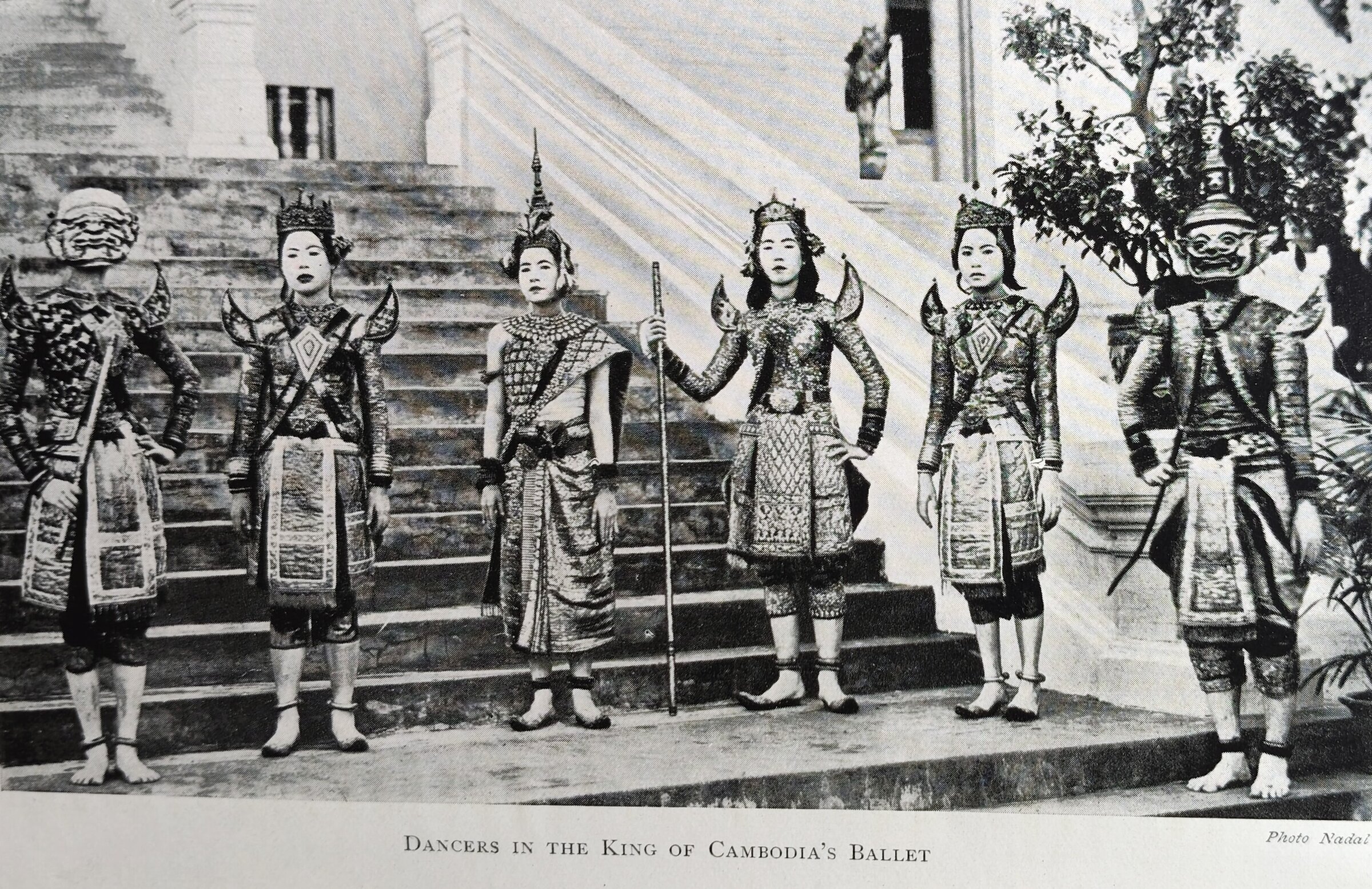

[…] After dinner the King of Cambodia, with the King of Luang-Prabang and the guests, adjourned to “the Hall of Festivals” to attend a performance of the famous Cambodian ballet. His Majesty had lavished money on the renewal of the traditional costumes, and the little girl dancers shone and sparkled like a casket of jewels. How strange and yet how fascinating were their movements! Their faces, powdered dead white, remained stolidly expressionless, and it was only by the refined and delicate actions of their little bodies and of their limbs that the story of the play-ballet was maintained. The music tinkled, now fast, now slow, and with strange bendings and posings, with extended arms and hands bent back, with fingers alive with expression and deliberate steps full of meaning, the dance proceeded. With what delicate grace the small Prince made love to the little Princess! How fierce the gestures of the masked demons! How warlike the tread of the tiny soldiers!

Royal Ballet first dancers in 1928, some of them having rehearsed in front of George Groslier’s camera the year before [photo by Nadal].

Royal Ballet first dancers in 1928, some of them having rehearsed in front of George Groslier’s camera the year before [photo by Nadal].

After the ballet there was a display of fireworks on the large, open space outside the Palace onto which the galleries of “the Hall of Festivals” look down. These fireworks, I was told, had all been made in Phnom-Penh. On the whole they were successful though, as generally happens with all home-made things there were one or two failures, but luckily no accidents. It was on this occasion that I was introduced for the first time to a novel kind of firework. They made little or no display, but gave forth the most appalling shrieks and groans, filling the whole air with a really terrifying din. The object, I believe, was to keep away evil spirits. Of their success in accomplishing this useful task no one who had listened to their infernal noises could have any doubt.

The following day King Sisowath Monivong rode through the streets of his Capital in State and performed the prescribed rites at certain appointed places. What a glorious procession it was! The central figure was of course the King, who for the first stage of his progress was borne on a gilded palanquin, surrounded by Princes and his Ministers. At the Bridge of the Sacred Serpents he alighted, and after a short ceremony discarded the crown that he had been wearing, replacing it by a second one. He then continued his parade seated on a throne raised high upon a small, gilded carriage drawn by six ponies and with the parasol of State over his head. A second halt was made at the foot of the temple hill of Phnom-Penh, and once more the crown was changed. From this spot the King continued his way mounted upon a richly caparisoned pony. It was thus that he arrived at the French Residency which was adequately decorated for the occasion. Here His Majesty alighted to perform the culminating rite of the Royal Progress. A very small number of guests were specially invited to this function, which took place in the salon of the Residency. The King was seated on a brocaded sofa, while a few of the most important members of his Court stood behind and beside him. The French Governor-General was seated at his right and the French Resident on his left. The eight Brahman priests entered the room in single file, one bearing a lighted taper and others carrying certain religious emblems of the Hindu faith. These priests stood in line in front of the King repeating prayers. The short ceremony over, champagne was served, the Cambodian official who handed the King his glass crouching side-ways to the ground in reverence. In this apartment I was able to obtain an excellent view of His Majesty, a man of very pleasant, kindly countenance, middle-aged, and dark brown in colour. Before the King left he placed still another crown upon his bare head, emblematical of full sovereignty, for he had now accomplished every ritual formality that the event of his coronation rendered necessary.

At the gateway of the Residency, with its guards of troops and sailors, the King mounted a State elephant, taking his seat in a domed howdah of much magnificence, and returned to the Palace. It was, indeed, a wonderful procession, a mixture of Oriental splendour and Oriental untidiness, with its flags and banners and religious emblems, its gorgeously attired courtiers seated cross-legged on their gilded palanquins in the shade of flat parasols of every size and colour held over them by their attendants; its antique little cannon on rough wooden carriages, pulled along at the end of long ropes; its long line of elephants amongst them the sacred white one-with gay howdahs and many-coloured trappings; its host of Palace servants, some in new silks and satins, others almost in rags, and most of them smoking; its Chinese and Indian delegations; its priests in yellow robes, and its soldiers and policemen in uniform, and its bands of music with every imaginable kind of instrument and all pro-ceeding with very little attempt at order, a leisurely throng sauntering through the streets, chatting pleasantly as they went as though unconscious of the crowd of admiring native men and women, and of the open-eyed, happy, thrilled children that lined the roadways. And from the howdah of his elephant the good-natured King smiled and waved his cigarette in answer to the people’s acclamations‑a small, dark figure wrapped in gold brocade. The greatness of the Cambodian race may have departed, but they still know how to crown a King in Phnom-Penh. [p 306 – 13].

Angkor

Not being an archaeological buff, the author nevertheless felt necessary to travel to Angkor, where he had only praise for the “large, cool rooms opening to a verandah” at the Auberge des temples, right in front of Angkor Wat. Braving vertigo (“the floor of the sanctuary is at a height of forty feet”), he climbed to take in the view and muse about transient civilizations, repeating the cliché of a doomed civilization :

Such immensities of stone, such untold labour, such mastery of detail skilfully distributed, cannot fail to arouse a feeling of oppression. One feels lost in such immensity, in such daring. From the colonnade that surrounds the sanctuary the traveller looks down on Angkor, with its wide extent of walls, its path-like enclosure, and its matchless regularity. […] It was dusk when I climbed for the first time to the sanctuary and stood at the feet of a statue of the Buddha, that has replaced the earlier Gods. Beyond is the Holy of Holies, a small, dark chamber buried in the base of the great central tower, dreary and unadorned, deserted, abandoned by the Gods and men. The sun had set, though for a few moments the afterglow hung suspended in the atmosphere, turning everything to rose and pink. Away beyond the temple precincts lay the jungle-covered plains, away and away to the faint horizon. A few birds on leisurely wing flew homewards to roost amongst the temple towers. A little band of priests climbed the steep stairway to light a tiny, floating wick at the feet of the image of Buddha and one thought of all that this place had been, in its time the centre of civilization and art, of faith and religion; the home of the Great Gods of South-East Asia. To-day the mighty are fallen.

[…] Days can be spent at Angkor, and weeks. Every hour a new beauty is discovered or one seen before is revisited. The bas-reliefs of the long galleries are a joy, portraying with classical dignity and art the life and times of Angkor’s greatness. Everywhere the eye falls upon exquisite detail, exquisitely accomplished the lintels of doors and windows, the little sculptured dancers that adorn the walls. Centuries have passed since their beauty and their skill stirred the hearts of Kings and priests and worshippers, but their effigies remain to-day in the cold stone and smile upon the passer-by. What magnificence, what grandeur, what colour, what zeal these precincts must have witnessed the sanctity of Kings and the mysteries of worship. To-day the corridors the Khmer Kings trod in all their magnificence reek of the bats that haunt their gloomy roofs. The mighty have fallen indeed, but they have left behind them a monument unrivalled and superb. [p 314 – 6]

The Southeast Asian Way of Life

There are many insightful notations on Siamese, Malaysian and Indonesian cultures in this pleasant travelogue, ending with considerations on the economic and political role of Chinese communities around Southeast Asia, but it was probably at the start of his long journey, previsbly in the then British colony of Burma (modern Myanmar), that the seasoned reporter felt there was a particular worldview at work in the diverse countries of the region, in which religion, ancestral superstitions, community obligations, were quite harmoniously combined with a profound acknowledgment and acceptation of the world as it was, not as it ‘should’ be. Through a heated discussion with a Scottish expatriate in Rangoon (Yangoon), he brushed the following portrait of ‘The Burman’:

The Burmans live their life in the open. Even the interior of their houses is disclosed to the public view when the bamboo screens that form the walls are raised. The status of their women is very high, and well deserved. Their family affection is evident. Religious in that they repair to the pagodas and listen to the word of the Teacher, the Burmans at the same time love pleasure and indulge in it. Their “Pwes” — theatrical performances — are thronged. Their religious festivals are gay with laughter and happiness. Their cleanliness and love of simple finery are proverbial. They are a delightful people.

It was a practical business Scotchman, long settled in Burma, who gave me in a few words a list of the bad qualities of the Burman and finally confirmed my good opinion of these happy children of the East. “The Burman,” he said, “has no stability and is never serious” (O lucky Burman.) -“He pays no attention to business and has no ambition to be prosperous, and never thinks about the morrow”- (Wise, fortunate Burman, how do you accomplish it?)- “He laughs all the time”- (Tell me your secret, Burman.) — “He is too amorous” — (Of course you are, and how can you help it when your women are so attractive?) — “He seems to think life is made for pleasure”- (Alas, alas, we cannot think that any longer.) — “He won’t put a suffering animal out of its misery”- (Fie, fie, Burman, that is bad. We are so compassionate that we kill all our pheasants and our foxes while they are still strong and well, lest they should suffer later on. You must be kind, O Burman.) — “He makes a bad domestic servant” — (Of course you do, of course you do. So should I.) — “Though by religion he is a Buddhist he is superstitious and believes in ‘Nats’, good and evil demons” — (Naturally, because you know that they really exist, the naughty “Nats”, in those wonderful jungle forests of yours. You propitiate them with offerings and build them little houses and shrines, and when they are troublesome you drive them out with great noises. How can you help believing in them? Keep your “Nats” and your faith, O delightful Burman! Perhaps in the end you will have to become like us, who believe in little or nothing) — and my business friend added: “They are so foolish, the Burmans. My wife and I have tried over and over again to train them, but they can never understand our Scotch ways.” — Of course you can’t, dear Burman, of course you can’t. Nor can I. The foreigner is taking most of what your country has to give but don’t let him take your “Nats” or your Faith or your joyous laughter. Keep those, for they are invaluable. The foreigner will go home a rich man and will likely buy a deer-forest and men will call him “laird”, but he will never laugh as you do and never have your great measure of faith or your happiness. Shut your ears to the music of the West. Be what God made you, the gayest and the most gracious of men and women, and if ever at times you are sad, go out and watch the children flying kites and the youths playing “Chin-lon” and thank God for the sunshine of your land and the sunshine of your hearts, for your joy of life, for the monks in their yellow robes, for your golden tipped pagodas, for the giant jungle trees and the bright colour of your clothes. Sit up all night at your festive Pwes and watch the little dancers, the clowns, the jugglers, and the marionettes. Go to the pagodas and hold your hands reverently before the image of the Buddha the Great Teacher, and trust in your next incarnation you may be a Burman over again, a delightful happy laughing Burman — just as you are to-day, and pray fervently that never for your sins may you be reincarnated north of the Tweed.

The Government of Burma may have successfully ridded the country of Dacoits, those unpleasant highwaymen who rendered life so unnecessarily adventurous for a long time after the British occupation, but it will never dislodge the “Nats”, the invisible little demons that haunt the earth, the rivers, and the tops of the jungle trees and play their pranks upon a long-suffering population. They are not all bad, the “Nats”, for there are some who are inclined to assist the necessitous and to checkmate crime, to cure an illness or to further a love affair, but the majority of them are distinctly naughty. [p 33 – 4]

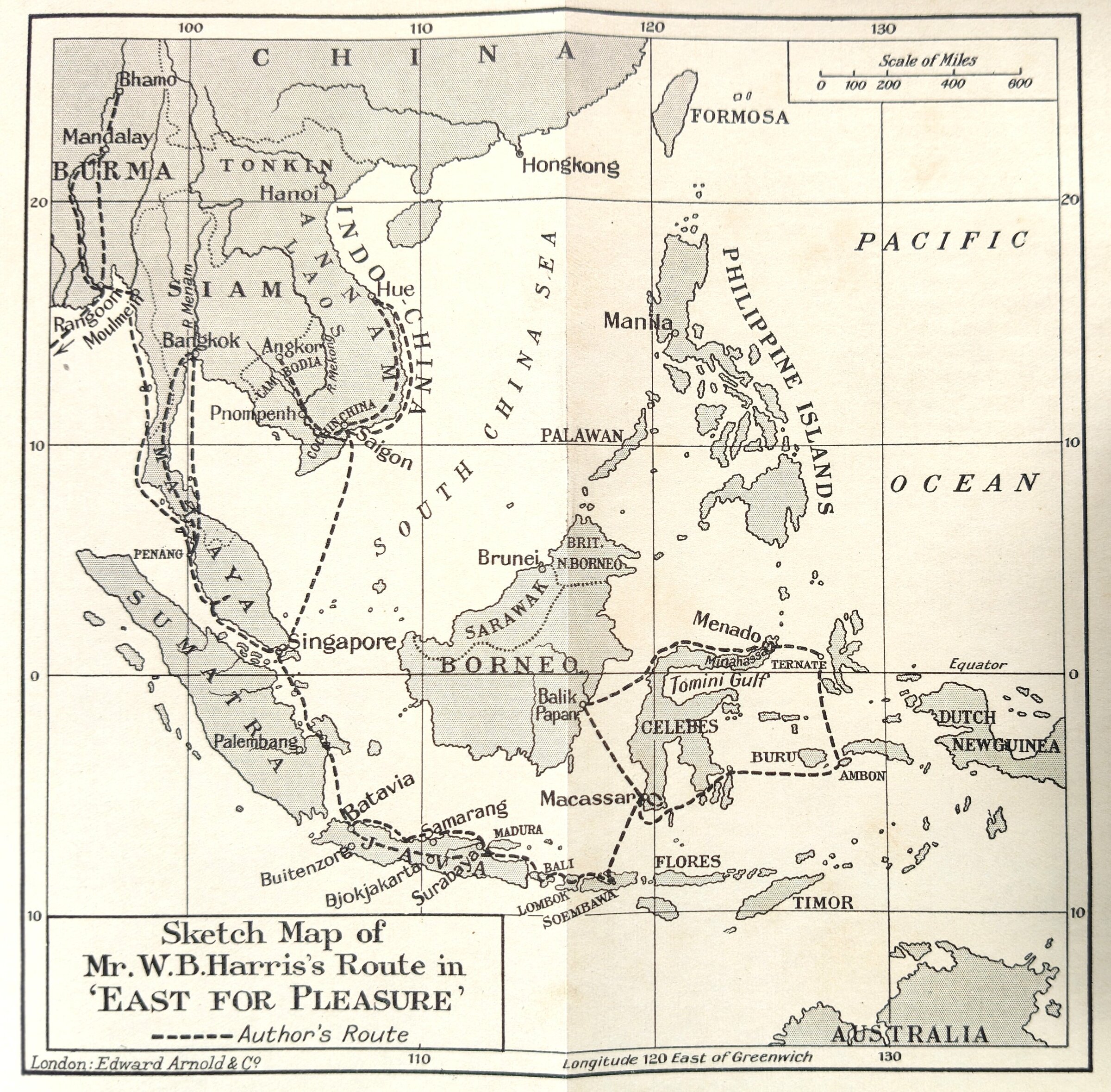

Walter B. Harris’ itinerary, November 1927 — August 1928.

CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- PART I: BURMA

- BY THE IRRAWADDY TO MANDALAY: 1

- MANDALAY TO BHAMO: 12

- THE BURMAN: 31

- MOULMEIN TO PENAN: 39

- PART II: SIAM

- THE KINGDOM OF SIAM: 50

- BANGKOK: 60

- BANGKOK TO SINGAPORE: 79

- PART III: THE NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES

- JAVA: 91

- AN EXCURSION IN JAVA: 119

- BALI: 130

- AN EXCURSION IN BALI: 147

- SURABAYA TO MACASSAR: 166

- A LITTLE TOUR IN SOUTHERN CELEBES: 175

- MACASSAR TO MENADO: 194

- AN EXCURSION IN MINAHASSA: 207

- MENADO TO THE TOMINI GULF: 222

- BACK TO MENADO: 234

- THE MOLUCCAS: 250

- AMBON TO SINGAPORE: 264

- PART IV: FRENCH INDO-CHINA

- SAIGON TO PHNOM-ΡΕΝΗ: 280

- PHNOM-PENH: THE CORONATION OF THE KING OF CAMBODIA: 300

- ANGKOR: 314

- SAIGON TO HUẾ: 325

- HUẾ AND THE COURT OF ANNAM: 342

- THE ANNAMITES: 369

- PART V: THE CHINESE ABROAD

- THE CHINESE ABROAD: 379

- INDEX: 391

Tags: King Monivong, 1920s, travel books, English travelers, French Protectorate, National Museum of Cambodia, movies, Burma, Siam, Annam, Bali, tourism, Celebes Islands, Chinese diaspora

About the Author

Walter B. Harris

Walter Burton Harris (29 August 1866, London – 4 April 1933, Malta [buried in Tangiers, Morocco]) was a journalist, writer and traveler who settled in Morocco at age 19, where he achieved fame with his work as special correspondent for The Times of London, traveled through the Caucasus, Persia, Turkistan, Irak and Yemen, and got involved in diplomatic imbroglios between England, French, Greece and Germany until he settled down as a leisure traveler, visiting Angkor and Southeast Asia in the late 1920s.

The son of a wealthy British shipping and insurance broker, W.B. Harris was from the start an avid traveler ready to immerse himself in the uncharted territories of Morocco’s mountains and Berber tribes, quickly learning languages (French, Spanish and North African Arabic) and always prone to disguise himself in tribal garments, not unlike another maverick British explorer, T.E. Lawrence. Unlike ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, however, he didn’t hide his homosexuality, only briefly marrying Mary Saville, a daughter of John Charles George Savile, 4th Earl of Mexborough (1810−1899) and making cosmopolitan and open-minded Tangier his home for his entire life.

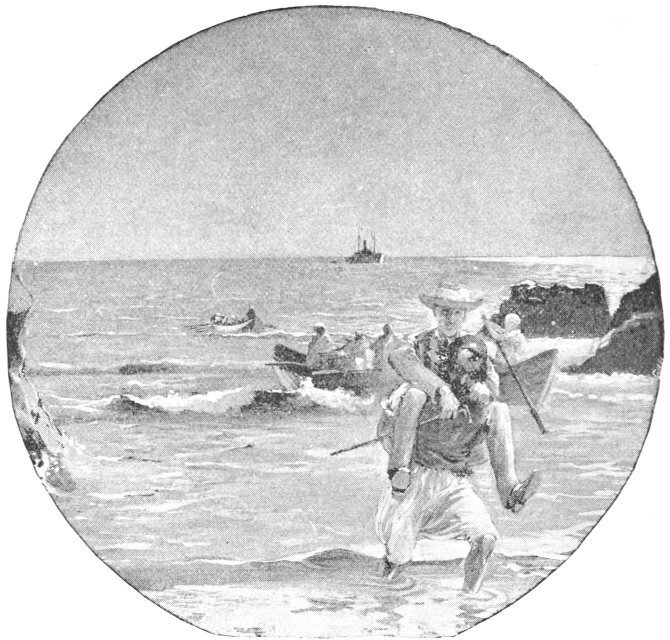

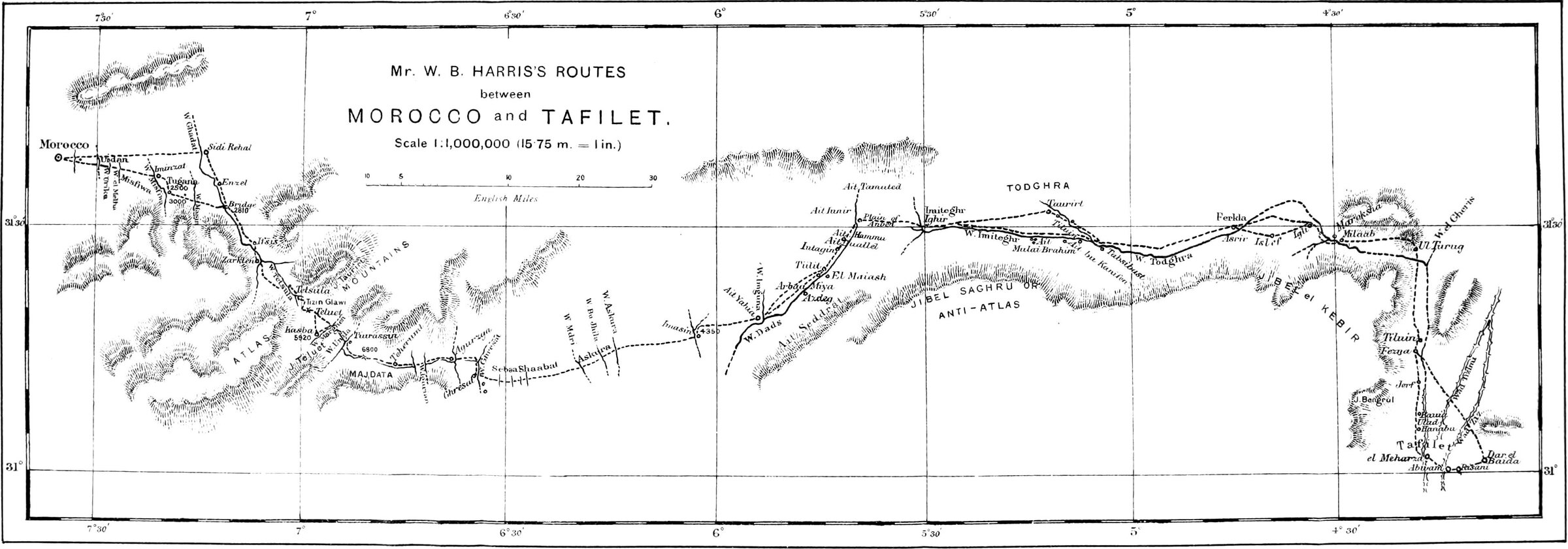

Unafraid of the most rugged mountains (above, his 1893 itinerary through the Atlas), W.B. Harris wasn’t the typical macho explorer of the time, depicting himself his quite comical landing at Safi آسفي, Morocco, piggyback on his manservant. [illustrations from his book Tafilet: The Narrative of a Journey of Exploration.]

Unafraid of the most rugged mountains (above, his 1893 itinerary through the Atlas), W.B. Harris wasn’t the typical macho explorer of the time, depicting himself his quite comical landing at Safi آسفي, Morocco, piggyback on his manservant. [illustrations from his book Tafilet: The Narrative of a Journey of Exploration.]

Unafraid of the most rugged mountains (above, his 1893 itinerary through the Atlas), W.B. Harris wasn’t the typical macho explorer of the time, depicting himself his quite comical landing at Safi آسفي, Morocco, piggyback on his manservant. [illustrations from his book Tafilet: The Narrative of a Journey of Exploration.]

At ease with royalty and high-ranking politicians, he also demonstrated his adventurous and fearless streak while exploring the Rif region and gaining the trust of mountain chieftains such as Moulai Ahmed er Rasuni ولاي أحمد الريسوني [name Westernized as ‘Raisuli’], a leader of the Jebala tribal confederacy who died in April 1925 after having been imprisoned by his rival Abd el Krim. Initially, he had been captured by Rasuni’s men and held hostage (for “three weeks of a terrible experience”, according to the New York Times on 14 July 1903, for nine days and without much hardship, if we trust his own account in his acclaimed 1921 book, Morocco That Was ). He was the confidant of Moroccan sultans, including He interceded with Sultan Moulay Abd el Aziz, with whom he interceded on behalf of Meknes Jews who had been razzied by brigands.

Harris liked to enrich his travelogues with the help of illustrators: 1) ‘Georgian Types’ [in From Batum to Baghdad, 1896], 2) ‘Woman of Dads’ for Dades Valley مضايق دادس, Morocco. [in Tafilet..., 1895

As a young and daredevil correspondent for The Times of London (officially since 1906), Harris resigned himself to accepting the decline of British worldwide influence in Morocco — which became a French Protectorate in 1912 -, Yemen (where he was special correspondent in the 1890s), Greece (he covered the domestic convulsions in Athens in 1915). His hostility towards France had melted away by the time Great Britain and France settled their Entente Cordiale in 1904. In Tangiers, he befriended the secretary of the French legation, Maurice Delarue de Beaumarchais (1872−1932), a great-grandson of P.A. Caron de Beaumarchais, the author of Mariage de Figaro, and Beaumarchais’s wife, Marie Louise Lagelouze (1880−1957), accompanied him in some of his forays into Berber country, taking blurred photographs. Harris later implied that he had worked with the Admiralty intelligence service during World War I. In any case, France awarded him the Legion of Honour and the title of Commander of the Oiussam Alaouite of Morocco.

A piece of trivia: Walter Harris, also a correspondent for The Times, rescued in 1908 a young Indiana Jones from a Marrakesh slave market in George Lucas’ The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones: Volume One, The Early Years (shot on location in 1999, with Corey Carrier as Indiana Jones, DVD released in 2008). The TV educational program spotlighting historical figures such as T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), initially titled The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles or Young Indy, was reformatted and repackaged several times. In the movie, young Indiana Jones meets Harris in 1908 in Tangiers, when his family went to stay with him, and the journalist teaches the young boy to disguise himself. Captured by slave traders with his friend Omar, Indy is finally rescued by Harris, who pays the ransom for both boys. [see Indiana Jones Fandom blog.]

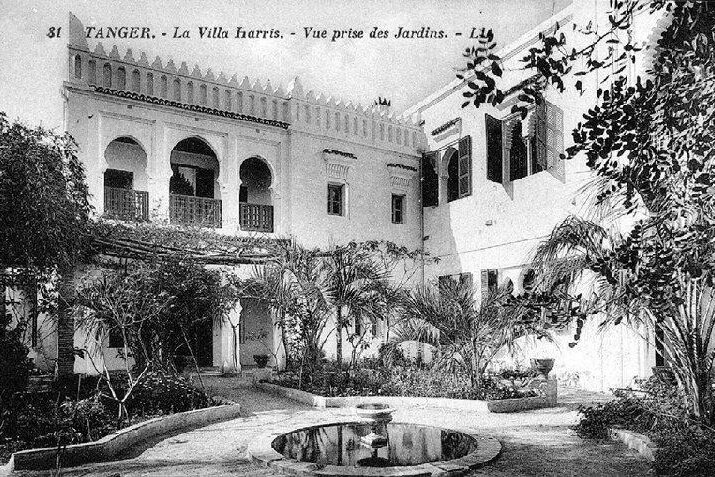

1) ‘Villa Harris’ in Tangiers, on the road to Cape Malabata [1909 postcard reproduced on TangerRetro blog]. 2) Used as a casino, then as a Club Med resort until 1992, the villa was abandoned during two decades before being restored and converted into a museum in 2021[photo by Stelmaris via Wikicommons, 2024].

1) ‘Villa Harris’ in Tangiers, on the road to Cape Malabata [1909 postcard reproduced on TangerRetro blog]. 2) Used as a casino, then as a Club Med resort until 1992, the villa was abandoned during two decades before being restored and converted into a museum in 2021[photo by Stelmaris via Wikicommons, 2024].

1) ‘Villa Harris’ in Tangiers, on the road to Cape Malabata [1909 postcard reproduced on TangerRetro blog]. 2) Used as a casino, then as a Club Med resort until 1992, the villa was abandoned during two decades before being restored and converted into a museum in 2021[photo by Stelmaris via Wikicommons, 2024].

More than Lawrence of Arabia, Harris had been prone to embellish his own exploits, but In November 1927, after four consecutive years of covering the French-Spanish anti-rebellion efforts in the Rif, “tired and sick of the cruelties of war”, Harris embarked to a journey of eigth months through “Southeast Asia and the Dutch Archipelago” that he described as a “pleasure trip” but with The Times covering his travel expenses, in his own words out of “the consideration and generosity of that great newspaper” to him. Angkor was amongst “the many places [he] desired to see.” His travel account, East for Pleasure (1929), was utterly devoid of self-promotion.

By then, Harris was a dignified member of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1933, he took another reflective journey to places he had visited before in the Near and Middle East, and was crossing back the Mediterranean sea when he had a stroke aboard the ocean liner. He died at King George V hospital in Malta, and was later buried at Tangier’s Anglican cemetery.

Publications

- The Land of the African Sultan: Travels in Morocco, 1887, 1888, and 1889, London, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1889.

- A Journey through the Yemen, and some general remarks upon that country, Illustrated from sketches and photographs taken by the author, Edinburgh-London, William Blackwood, 1893.

- Danovitch and Other Stories, Edinburgh-London, William Blackwood and Sons, 1895.

- Tafilet: The Narrative of a Journey of Exploration in the Atlas Mountains and the Oases of the North-west Sahara, illustr. by Maurice Romberg, Edinburgh-London, William Blackwood, 1895 [Project Gutenberg ebook].

- From Batum to Baghdad by way of Tiflis, Tabriz and Persian Kurdistan, London, William Blackwood & Son, 1896.

- Morocco That Was, London, William Blackwood & Sons, 1921; repr. by Eland, 2002; repr. Negro Universities Press, 1970; FR Le Maroc disparu- Anecdotes sur la vie intime de Moulay Hafid, de Moulay Abd el Aziz et Raissouli, tr. by Paul Oudinot, Paris, Plon, 1929.

- France, Spain and the Rif, London, E. Arnold, 1927.

- East for Pleasure: The Narrative of Eight Months’ Travel in Burma, Sian, the Netherlands East Indies and French Indo-China, London: Edward Arnold & Co., New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1929.

- East Again: The Narrative of a Journey in the Near, Middle and Far East, London: Butterworth, New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1933.

Main photo: a portrait of Walter B. Harris by Sir John Lavery (1907).