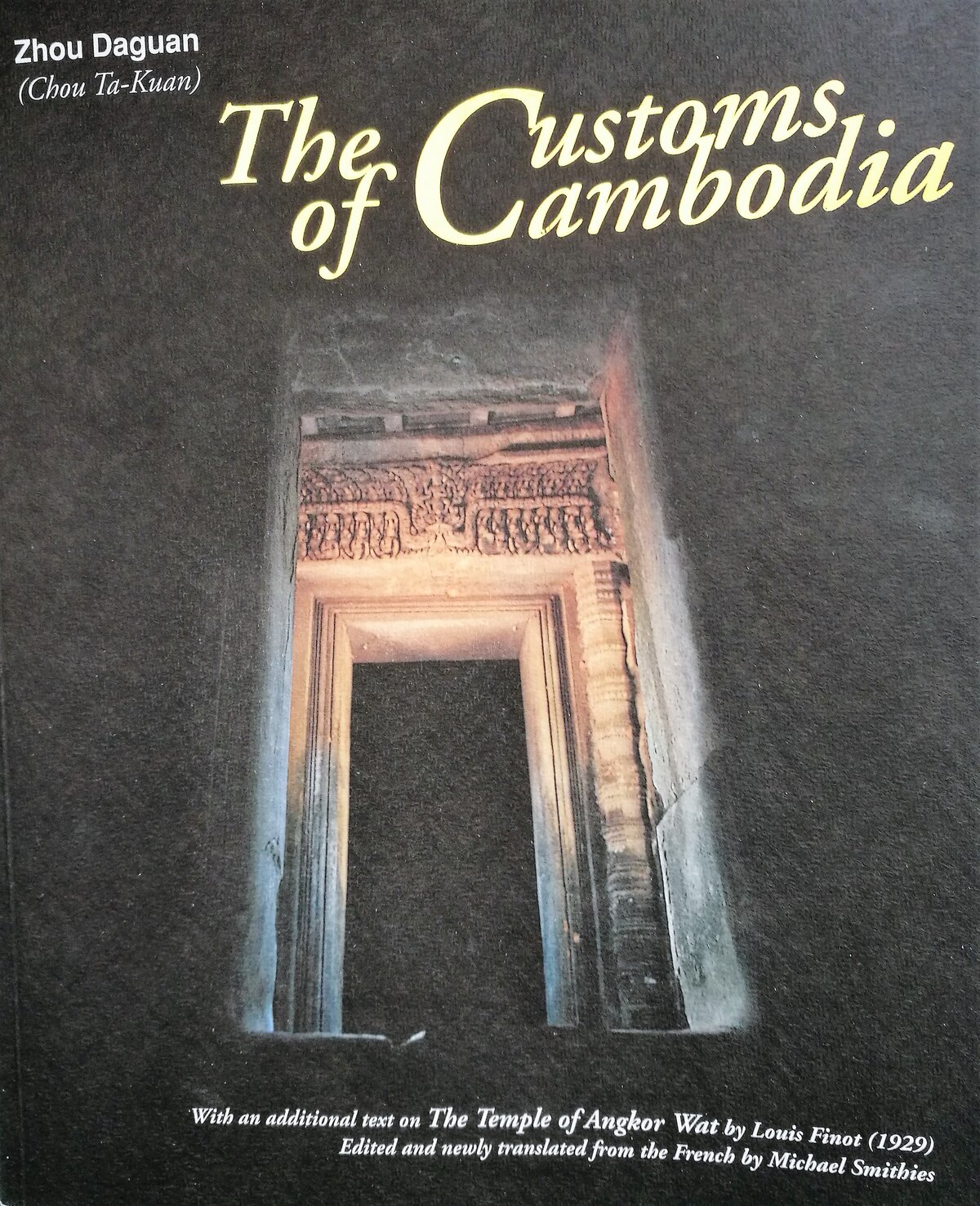

Zhou Dagan's "Customs of Cambodia"

by Michael Smithies & Zhou Daguan

Another translation of the most ancient account of the life in Angkor by the Chinese merchant and traveler Zhou Daguan

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, hardback

- Publisher

- Siam Society, Bangkok

- Edition

- 4th edition

- Published

- 2006

- Authors

- Michael Smithies & Zhou Daguan

- Pages

- 147

- ISBN

- 978-9748298511

- Language

- English

This richly illustrated book is a new translation from the French of Zhou Daguan’s Customs of Cambodia, from Paul Pelliot’s 1902 translation. About Pelliot’s work (BEFEO II, 1902, pp. 123- 177), the author notes that Pelliot “worked at a revision of his translation until 1924, after which he does not appear to have returned to the manuscript. He had begun very detailed notes to his revised translation, but unfortunately these only go as far as section 3 (out of a total of 40). His revisions were published posthumously in 1951. Two contributions from Chinese scholars have supplied some corrections to Pelliot’s text, and their findings are incorporated here: Xia Nai’s Zhenla fentuji jiaozhu (1981) and Yang Baoyun’s ‘Nouvelles études sur l’ouvrage de Zhou Daguan’, in Recherches nouvelles sur le Cambodge, Paris. EFEO.1994. Études Thématiques 1. pp.227 – 234.

While the number of photographs dedicated to Angkor Wat can be surprising — after all, Zhou Daguan mentioned many buildings, including Prasat Baphuon and Angkor Thom Royal Palace, but never visited Angkor Wat proper, to which it refers as “the tomb of Lu Ban” – , this edition is completed by a useful index, allowing to search among the many topics covered by the famous Chinese traveler.

The author’s English version was commissioned in April 2000 by the Siam Society in order to substitute the only English translation (also from the French) previously produced by J. Gilman d’Arcy Paul in 1967. The latter one, reedited in 1988, 1993, and 1999, was deemed inaccurate — yet we at Angkor Database are fond of his style.

Peter Harris, who translated Zhou Daguan’s original Chinese text (or some of its numerous versions) into English and published it in 2007, noted that “Smithies takes into consideration some of the variants in the Chinese text that have come to light in recent decades. But he himself acknowledges he does not read Chinese, and his translation inevitably suffers from being two removes from the original. An earlier translation into English by J. Gilman d’Arcy Paul suffers from the same problems, in a more pronounced form.” (A Record of Cambodia, p15)

In annex, the author translated into English Louis Finot’s 1929 essay ‘The Temple of Angkor Wat’ (ÉFEO, Mémoires archéologiques vol II, complete with a note by Jacques Dumarcay.”

We can find here also the first English translation of Paul Pelliot’s preface in its integrality:

The only description of Angkor at the time of its splendour is that in the Mémoires sur les coutumes du Cambodge [The Customs of Cambodia) (Zhenla feng duji) [Tchen la fong t’ou ki from the pen of Zhou Daguan Chou Ta-kuan, Tcheou Ta-kouan].

Zhou Daguan, with the family name of Caoting Yimin [Ts’au-t’ing yi-min), came from Yungjia [Yong-kia] in Chekiang [Tchö-kiang]. In 1296 – 1297, he accompanied a Chinese embassy which spent nearly a year in Cambodia. On returning to China, he drew up an account of his journey, probably right away, and certainly before 1312; he was still alive in 1346. Shortly after the fall of the Mongol dynasty in 1368. the Mémoires sur les coutumes du Cambodge were incorporated in a compilation, essentially comprising extracts, of one hundred chapters, the Shuofu (Chouo fou from the pen of Tao Zongyi [T’ao Tsong-yi]. But this Shuofu is not the standard edition of 120 chapters which appeared in 1646 – 1647; in this, the Mémories were reproduced, with the absence of one page, following the 1544 edition appearing in the Gujin Shouhai [Kou kin chouo hai]; this, directly or indirectly, is the basis of the half-dozen editions of the Mémories which were available until recent times. However, several manuscript copies existed, often inaccu- rate or fragmentary, of the original Shuofu, one of these has recently been published by the Commercial Press in Shanghai. The text is generally identical to that in the Gujin Shouhai, which is certainly a copy of the Shuofu itself. It is however important to have, for the first time, a text which does not derive from the 1544 edition.

The Shuofu contains hardly any complete works. So, although the Mémories, such as we have them, form a coherent whole, one wonders if the text is not cut. This is what a bibliophile in the middle of the seventeenth century. Qian Zeng [Ts’ien Ts’eng], claimed; speaking of a manuscript in his possession, he wrote: “This volume was copied from a Yuan manuscript version. The edition of [Gujin] Shouhai has contradictions, errors, and omissions; six or seven tenths of the original is lacking, it hardly gives an idea of the book. Unfortunately, the few manuscript copies of the Mémories which I have been able to trace seem only to supply the usual text, and the few early quotations which I have been able to gather are usually found there. There is, though, one exception. The Chengzhai Zaji [Tch’eng tchai tsa ki] of Lin Kun [Lin K’ouen], which must have been compiled fairly early on in the fourteenth century, and for which Zhou Daguan himself wrote a preface in 1346, quotes a pamage from the Mémories which is found there, but it is quoted with a final phrase, certainly original, which is missing from the present text. Until now, this is the only trace of a more complete text which Quian Zeng was still aware of three centuries later.

The work attracted the attention of Abel Rémusat, who translated it in 1819. I myself produced a new version in 1902 in the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient, but offprints of this are very rare. I have taken advantage all the more willingly of the chance to publish the Mémories again, since my translation of 1902 could be refined or improved at several points.

Even if the text of the Mémoires, such as we have it, is not complete, it is of exceptional interest. The accounts of the early Buddhist pilgrims, in particular of Xuan Zang [Hiuan-tsang), makes one appreciate the detailed accuracy with which Chinese travellers compiled the notebooks of their accounts, Zhou Daguan visited Cambodia when it was still very prosperous, and gives a lively and exact account of the country. However, the decline was not far off: the Siamese were at hand. Already the monks in Cambodia were called by a Siamese name, which labriel San Antonio noted three centuries later, although he is forgotten today. Above all Zhou Daguan speaks of the recent invasion of the Siamese and the destruction this caused. I can hardly avoid attributing to the Siamese the successive removals of the Cambodian capital from Angkor to Babaur, Lovek, and finally Phnom Penh.

Tags: Zhou Daguan, travelogue, history, translations, Angkor Thom, French researchers, Angkor Wat, Baphuon

About the Translator

Michael Smithies

Michael Smithies (1932 — 2 Jan. 2019, Bangkok) was a British historian based in Bangkok, a translator of numerous texts on Siam and Cambodia from French into English — in particular studies by French archaeologist Jacques Dumarcay, Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h and Bernard-Philippe Groslier in modern times -, an author of numerous books on Siamese and Southeast Asian civilizations.

After majoring in Mediaeval Studies and French language at Oxford University — on an ‘open scholarship’ -, Prof. Smithies arrived in Bangkok as an Education Officer for the British Council in 1960. At that time, he became an active member of the Siam Society and a frequent contributor to the Journal of Siam Society (JSS), of which he was twice Honorary Editor (1969 – 71 and 2002-09). He worked with the British Council in Phnom Penh (1964−5) before returning to Bangkok, resuming his research on the history of Kingdom of Siam’s foreign interactions in the 16th-17th centuries, with an emphasis on France. His translation of Zhou Daguan’s Customs of Cambodia (2001) was made from Paul Pelliot’s first edition of the famous 1296 Chinese travelogue to Angkor published in 1902.

From 1971 to 1985, he pursued a roving academic career as lecturer in French at the University of Hong Kong (1971−4), British Council Director of the Staff English Language Training Unit at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta (1974−6), professor of Language and Social Science at the University of Technology in Lae, Papua New Guinea (1976 – 1982), associate professor in communication studies at the new Nanyang Technology University, Singapore (1982 – 5), then back in Bangkok as visiting professor at the Asian Institute of Technology’s English Language Centre, special lecturer at Burapha University, Bang Saen, and adviser to United Nations ESCAP staff training unit from 1987 to 1992, when he retired.

Involved in Bangkok’s cultural scene for decades, Smithies was known for organizing classical music concerts and setting up exhibitions of Thai modern artists, locally and in the UK. He spent his last decades between his vacation house in Coulon (France) and the village of Bua Yai, Isan (Thailand), alongside his companion, Thai artist Uthai Traisiwakul (see Tej Bunnag, ‘Michael Smithies, 1932 – 2019’, JSS 107 – 1, 2019: 173 – 6.) He was made Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government in 2006.

Publications

- [with Tej Bunnag] In Memoriam Phya Anuman Rajadhon: Contributions in Memory of the Late President of the Siam Society, Bangkok: Siam Society, 1970.

- Discovering Thailand : guidebook and photographs by Achille Clarac, Bangkok : Siam Communications, 1972. 458 p.

- A Javanese Boyhood : an ethnographic biography, Singapore : Federal Publications, 1982, 145 p. ISBN 9971404214 [with illustrations by Philip Teo and Yuli].

- A Singapore boyhood, Singapore/Kuala Lumpur : Federal Publications, 1984, 114 p. [illustr.]. ISBN 9810190336.

- [tr. and pres.] The Discourses at Versailles of the First Siamese Ambassadors to France 1686 – 7, together with the list of their presents to the Court, Bangkok: Siam Society, 1986.

- The Mons : collected articles from the Journal of the Siam Society, Bangkok: Siam Society, 1986, 82 p. ISBN 9748298019.

- “The Ladies at Versailles on 1st September 1686,” Siam Society Newsletter (SSN) 2 – 2, June 1986.

- Old Bangkok, Singapore : Oxford University Press, 1986, 83 p. [illustr.]. ISBN 0195826868.

- [ed. and tr.] A Week in Siam January 1867, by the Marquis of Beauvoir, Bangkok: 1986, 102 p. ISBN 9748298035.

- Description of Phetchaburi, Bangkok: Siam Society, 1987, 107 p. ISBN 9748298108.

- Yogyakarta : cultural heart of Indonesia, Singapore : Oxford University Press, 1986, 110 p. [illustr.], ISBN 0195826531.

- [tr.] Early accounts of The Siamese embassy to the Sun King : the personal memorials of Kosa Pan, Bangkok : Editions Duang Kamol : Chatchamnai doi Duangkamonsamai, 1990, 141 p. ISBN 9742105057.

- [compil. and intr.] Descriptions of old Siam, Kuala Lumpur/New York : Oxford University Press, 1995, 319 p. ISBN 9676530832.

- [ed.] The Siamese Memoirs of Count Claude de Forbin 1685 – 1688, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1996.

- [ed. and pres.] A pilgrimage to Angkor by Pierre Loti (Julien Viaud), based on a translation by W.P. Baines, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1996, 126 p. [with 16 plates by Euayporn Kerdchouay].

- [ed.] The Chevalier de Chaumont and the Abbé de Choisy: Aspects of the Embassy to Siam 1685, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1997.

- [ed.] A Scottish sea captain in Southeast Asia, 1689 – 1723: Alexander Hamilton, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1997, 216 p.

- A resounding failure : Martin and the French in Siam, 1672 – 1693, Chiang Mai : Silkworm Books, 1998, 168 p. ISBN 9747100711.

- “Young Beauregard (c.1665 – c.1692) soldier of misfortune in Siam,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (JRAS), 3d series 8 – 2, July 1998: 229 – 235.

- A Siamese embassy lost in Africa 1686 : the odyssey of Ok-Khun Chamnan, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1999, 134 p. ISBN 9747100959.

- [ed.] The Talaings by Robert Halliday, Bangkok : Orchid Press, 1999, 172 p. ISBN 9748299112.

- Gulfs of Thailand : a collection of short stories, Chiang Mai : Silkworm Books, 1999, 144 p. ISBN 9747100894.

- “Madame Constance’s jewels.” JSS 88, 2000: 111 – 121.

- [tr. and pres.] The Customs of Cambodia by Zhou Daguan, Bangkok: Siam Society, 2001 [4th ed.], 147 p.

- Mission Made Impossible: The Second French Embassy to Siam 1687, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2000.

- [with Luigi Bressan] Siam and the Vatican in the Seventeenth Century, Bangkok, River Books, 2001.

- [ed.] The Diary of Kosa Pan (Thai Ambassador to France. June-July 1686), translated into English by Visudh Busayakul, introduced and annotated by Dirk Van der Cruysse, Chiang Mai : Silkworm Books, 2002, 82 p. [illustr.]. ISBN 9747551586.

- [tr.] Siam and the West, 1500 – 1700, by Dirk van der Cruysse, Chiang Mai : Silkworm Books, 2002, 583 p. ISBN 9747551578.

- [tr. and pres.] Three military accounts of the 1688 ‘Revolution’ in Siam by General Desfarges, Lieutenant de La Touché and Engineer Jean Vollant des Verquains, Bangkok : Orchid Press, 2002, 192 p. ISBN 9745240052.

- [ed.] Two Yankee Diplomats in 1830s Siam, Edmund Roberts and W.S.W. Ruschenberger, Bangkok : Orchid Press, 2002, 232 p. ISBN 9745240044.

- [tr. and ed.] Marcel Le Blanc: History of Siam in 1688, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2003.

- ‘Eclipses in Siam, 1685 and 1688, and their representation’, JSS 91, 2003: 189 – 204.

- Village vignettes : portraits of a Thai village, Bangkok : Orchid Press, 2003, 168 p. ISBN 9745240311 [with drawings by Uthai Traisiwakul].

- [tr. and ed.] Witnesses to a Revolution, Siam 1688: twelve key texts describing the events and consequences of the Phetracha coup d’ʹetat, and the withdrawal of French forces from the country, Bangkok: Siam Society, 2004, 220 p. ISBN 9748298558.

- [tr.] Architecture and its models in South-East Asia, by Jacques Dumarcay, Bangkok : Orchid Press, 2003, 127 p. ISBN 9745240273.

- [tr.] Muslims of Thailand, by Michel Gilquin, Chiang Mai : Silkworm Books, 2005, 223 p [illustr.]. ISBN 9749575857.

- [tr. and pres.] Angkor and Cambodia in the sixteenth century : according to Portugese and Spanish sources by B.-P. Groslier, Bangkok : Orchid Press, 2005, 196 p. ISBN 9745240532.

- [tr., preface by Jean Boisselier] The armies of Angkor : military structure and weaponry of the Khmers, by Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Bangkok, Thailand : Orchid Press, 2007, 191 p [illustr.]. ISBN 9789745240964. [1st English tr.]

- ‘The Chevalier de Fretteville (c.1665 – 1688), an Innocent in Siam’, JSS 101, 2013: 113 – 25.

- [ed.] 500 Years of Thai-Portuguese Relations, Bangkok: Siam Society and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2011.

- [ed. on his 80th birthday] Seventeenth century Siamese explorations; a collection of reprinted articles, Bangkok: Siam Society, 2012, 390 p.

About the Author

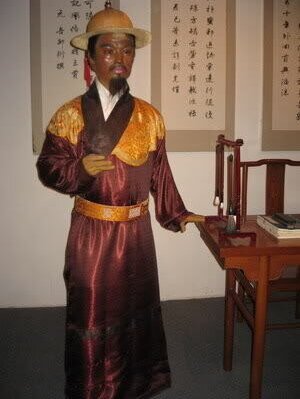

Zhou Daguan

Zhou Daguan (also Tcheou Ta-Kouan, Zhu Daguan) ch 周达观 , kh ជីវតាក្វាន់ (chiv takvan), vn Chu Đạt Quan, th โจวต้ากวาน (cho wta kwan)(c. 1270, Yongjia (modern Wenzhou) – ? shortly after 1346), a Chinese traveler under the Temür Khan (Emperor Chengzong), authored the sole written and direct account of the customs of Cambodia and the Angkorean power from the 13th century that has been preserved to our days.

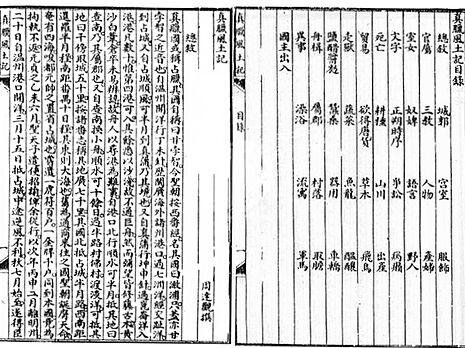

Instructed to join an imperial mission to Chenla in 1295, he arrived at Angkor in August 1296 and stayed near the court of King Indravarman III (also named Sri Srindarvarman) until July 1297. We know only a third of his account, The Customs of Cambodia (真臘風土記, Zhēnlà Fēngtǔ Jì, literally The Land and Social Conditions of Chenla), first translated into French by the sinologist Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat in 1819 (Description du royaume de Cambodge par un voyageur chinois qui a visité cette contrée à la fin du XIII siècle, précédée d’une notice chronologique sur ce même pays, extraite des Annales de la Chine, Paris, Imprimerie J. Smith, 1819), and later on by Paul Pelliot in 1902 (1) and posthumously in the 1951 edition edited by George Coedes and Paul Demieville. In 2007, the linguist Peter Harris completed the first direct translation from Chinese to modern English.

Coincidentally, Zhou Daguan’s travel to Angkor occurred the same year than “the trader and adventurer Marco Polo arrived back in Venice after twenty-five years’ absence. Legend has it that he was full of stories about his travels in China and other parts of Asia, and about the services he provided to the great khan Khubilai, the founding emperor of the Mongol dynasty then ruling China. That same year, 1295, a young man by the name of Zhou Daguan set sail from Mingzhou, a port on the southeast coast of China. Zhou was headed for Cambodia as part of a delegation sent there by Khubilai’s grandson Temür, who had come to the imperial throne on the death of his grandfather.” (cf. Peter Harris, A Record of Cambodia, p 6).

We still have to conjecture in which capacity Zhou Daguan joined the delegation, but we know he was not a diplomat acting for the Yuan dynasty, nor a trader. The “Summary of the General Catalogue of the Complete Library of the Four Treasures” of the Qing Dynasty, praising the book as “quite comprehensive and rich in meaning, with many details, which can make up for the missing parts of the Yuan History,” mentions its author as a “lettered man.”

As for the name Daguan 达观, which he used after his trip to Chenla, several interpretations have been given: “the one who saw everything”, “at ease in every circumstance”, “who sees the bright side of everything”.

Sinologist and Khmerologist Pascal Médeville is currently working on a novelized account of Zhou Daguan’s life and travels. And in December 2024, Princess Buppha Devi Dance School presented in Phnom Penh the first musical and dance production inspired by the journey of Zhou Daguan, លោក ជីវ តាក្វាន់ បានជួបនគរចេនឡា Zhou Daguan in the Kingdom of Chenla.

Angkor Database recommends the direct translation established from the ancient Chinese text into English by native Chinese Ms. Beling Uk and native Cambodian Solang Uk in 2010 and 2011. Xia Nai’s 1981 Chinese edition of the travelogue remains a reference. The first ever English version published in Bangkok in 1967, entirely from Pelliot’s French text (the1902 version), is mostly notable for its enigmatic author, John Gilman D’Arcy Paul.

Customs of Zhenla has also been translated into:

- Khmer: កំណត់ហេតុរបស់លោក ជីវ តាក្វាន់ អំពីប្រពៃណីនៃអ្នកស្រុកចេនឡា [Chiv Ta Kwan [Zhou Daguan]‘s diary about the traditions of the people of Chenla], tr. Ly Team Teng, 1971, Phnom Penh.

- Thai: โจวต้ากวาน, บันทึกว่าด้วยขนบธรรมเนียมประเพณีของเจินละ เฉลิม ยงบุญ [Record of Chenla’s customs and traditions], tr. Chalerm Yongbunkerd, 2014 (3d edition) — ISBN 978−974−02−1326−0.

- Vietnamese: Chu Đạt Quan, Chân Lạp phong thổ ký [Zhou Daguan, Chenla Land and People], tr. Lê Hương, Saigon, Kỷ Nguyên Mới Pub., Saigon, 1973 [excerpts in Vietnamese here].

- German: Walter Aschmoneit, Zhou Daguan, Aufzeichnungen über die Gebräuche Kambodschas, Studeingemienschaft Kambodschanische Kultur, 2006, 120 p., ISBN13 978 – 3000200724.

- Spanish: Vida y costumbres de Camboya, Relato del viaje de Zhou Daguan a Angkor, by Astrid Haardt, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013, 108 p., ISBN13 978 – 1478384496.

(1) In Antoine Brébion’s Dictionnaire Bibliographique, the entry Tcheou-Ta-Kouan states: ‘Lettré chinois du XIIIe siècle de notre ère, qui avait pour appellation Ts’ao-T’ING; il était originaire de Yong-Kia au Tchô-Kiang, il suivit l’ambassade chinoise envoyée au Cambodge en 1295, il revint en Chine en 1297. Le très érudit sinologue qu’est M. P. PELLIOT, de l’Ecole française d’Extreme-Orient, lui a restitué la paternité d’une relation intitulée Description du Cambodge, qu’ABEL DE RÉMUSAT avait attribuée à MA-TOUAN-LIN.’ [Chinese erudite from the 13th century CE, who was named Tsao-Ting, hailing from Yong-Kia in Tcho-Kiang. He followed the Chinese embassy sent to Cambodia in 1295, traveling back to China in 1297. The most learned sinologist Mr P. PELLIOT, from EFEO, has given back to him the autorship of a text titled ‘Description of Cambodia’, previously attributed to MA-TOUAN-LIN by ABEL DE RÉMUSAT.]